1

Legates, military tribunes and prefects of all ranks, even contubernales, since they came from families with clout or had distinguished themselves in some way, were not subject to the restrictions and disciplines placed on ranker soldiers and their centurions; it was, for instance, their right to leave military service at any time.

Thus, having arrived in Apollonia at the beginning of March, Gaius Octavius, Marcus Agrippa and Quintus Salvidienus were not obliged to live in the enormous leather-tented camps that stretched from Apollonia all the way north to Dyrrachium. The fifteen legions Caesar had assembled for his campaign went about their camping business indifferent to the presence of the upper-class men who would later assume a sometimes purely nominal command of their battle activities. Save for battle, the twain rarely met.

For Octavius and Agrippa, accommodation was not an issue; they went to the house in Apollonia set aside for Caesar and moved into a small, undesirable room. The penurious Salvidienus, eight years their senior and unsure of his duties or even his rank until Caesar defined them, reported to the quartermaster-general, Publius Ventidius, who assigned him to a room in a house rented for junior military tribunes not yet old enough to stand for election as tribunes of the soldiers. The problem was that the room already had a tenant, another junior military tribune named Gaius Maecenas, who went to Ventidius and explained that he didn’t want to share his room or his life with another fellow, especially a Picentine.

The fifty-year-old Ventidius was another Picentine, and had a personal history more ignominious by far than Salvidienus’s. As a little boy he had walked as a captive in a triumphal parade Pompey the Great’s father had celebrated for victories over the Italians in the Italian War. Childhood afterward had been a parentless ordeal, and only marriage to a wealthy widow from Rosea Rura country had given him a chance to rise. As the Rosea Rura bred the best mules in the world, he went into the business of breeding and selling army mules to generals like Pompey the Great. Thus his contemptuous nickname, Mulio, “the muleteer.” Lacking education and the proper background, he had hungered in vain for a military command, knowing in his bones that he could general troops. By the time Caesar crossed the Rubicon he was well known to Caesar; he attached himself to Caesar’s cause and waited for his chance. Unfortunately Caesar preferred to give him quartermaster’s duties than command of a legion, but, being Ventidius, he applied himself to this organizational job with dour efficiency. Be it regulating the lives of junior military tribunes or doling out food, equipment and arms to the legions, Publius Ventidius did it well, still hoping in his heart for that opportunity to general. It was getting closer. Caesar had promised him a praetorship next year, and praetors commanded armies, didn’t serve as quartermasters.

Understandably, when the wealthy, privileged Gaius Maecenas came complaining about a squalid Picentine moving into his room, Ventidius was not impressed.

“The answer’s easy, Maecenas,” he said. “Do what others in the same situation do—rent yourself a house at your own expense.”

“Do you think I wouldn’t, if there were any to rent?” gasped Maecenas. “My servants are living in a hovel as it is!”

“Hard luck” was Ventidius’s unsympathetic reply.

Maecenas’s reaction to this lack of official co-operation was typical of a wealthy, privileged young man: he couldn’t keep Salvidienus out, but nor was he prepared to move over for him.

“So I’m living in about a fifth of a room that’s plenty big enough for two ordinary tribunes,” Salvidienus said to Octavius and Agrippa in disgust.

“I’m surprised you haven’t just pushed him into his half and told him to lump it,” said Agrippa.

“If I do that, he’ll go straight to the legatal tribunal board and accuse me of making trouble, and I can’t afford to earn a reputation as a troublemaker. You haven’t seen this Maecenas—he’s a fop with connections to all the higher-ups,” said Salvidienus.

“Maecenas,” Octavius said thoughtfully. “An extraordinary name. Sounds as if he goes back to the Etruscans. I’m curious to meet this Gaius Maecenas.”

“What a terribly good idea,” said Agrippa. “Let’s go.”

“No,” said Octavius, “I’d rather fish on my own. The pair of you can spend your day on a picnic or a nice long walk.”

So when Gaius Octavius strolled alone into the room in one of the junior military tribunes’ buildings, Gaius Maecenas glanced up from his writing with a puzzled frown.

Four-fifths of the space was crammed with Maecenas’s gear: a proper bed with a feather mattress, portable pigeonholes full of scrolls and papers, a walnut desk inlaid with some very good marquetry, a matching chair, a couch and low table for dining, a console table that held wine, water and snacks, a camp bed for his body servant, and a dozen large wood-and-steel trunks.

The owner of all this clutter was anything but a martial type. Maecenas was short, plump, quite homely of face, clad in a tunic of expensive patterned wool, with felt slippers upon his feet. His dark hair was exquisitely barbered, his eyes were dark, his moist red lips in a permanent pout.

“Greetings,” said Octavius, perching on a trunk.

Clearly one look had informed Gaius Maecenas that he confronted a social equal, for he got up with a welcoming smile. “Greetings. I’m Gaius Maecenas.”

“And I’m Gaius Octavius.”

“Of the consular Octavii?”

“The same family, yes, though a different branch. My father died a praetor when I was four years old.”

“Some wine?” Maecenas asked.

“Thank you, but no. I don’t drink wine.”

“Sorry I can’t offer you a chair, Octavius, but I had to move my guest’s chair out to make room for some oaf from Picenum.”

“Quintus Salvidienus, you mean?”

“That’s him. Faugh!” said Maecenas with a moue of distaste. “No money, only one servant. I’ll get no contributions toward decent dinners there.”

“Caesar favors him highly,” Octavius said idly.

“A Picentine nobody? Nonsense!”

“Appearances can be very deceiving. Salvidienus led the cavalry charge at Munda and won nine gold phalerae. He’ll be attached to Caesar’s personal staff when we set out.” How very nice it was to be in a position of superior knowledge when it came to command affairs! thought Octavius, crossing his legs and linking his hands around one knee. “Have you had any military experience?” he asked sweetly.

Maecenas flushed. “I was Marcus Bibulus’s contubernalis in Syria,” he said.

“Oh, a Republican!”

“No. Bibulus was simply a friend of my father’s. We elected,” Maecenas said stiffly, “to stay out of the civil war, so I returned from Syria to my home in Arretium. However, now that Rome’s more settled, I intend to enter public life. My father thought it—er—politic—that I gain additional military experience in a foreign war. So here I am,” he concluded airily, “in the army.”

“But very much on the wrong foot,” said Octavius.

“Wrong foot?”

“Caesar is no Bibulus. In his army, rank has few privileges. Senior legates like his nephew Quintus Pedius don’t travel in the luxury I see here. I’ll bet you have a stable of horses too, but since Caesar walks, so does everybody else, even his senior legates. One horse for battle is mandatory, but more will earn you censure. As will a whole large wagon full of personal possessions.”

The liquid eyes gazing at this most unusual youth were growing more and more confused, the redness beneath the skin was deepening. “But I am a Maecenas from Arretium! My ancestry obliges me to emphasize my status!”

“Not in Caesar’s army. Look at his ancestry.”

“Just who do you think you are, to criticize me?”

“A friend,” said Octavius, “who would dearly like to see you shift from the wrong foot to the appropriate one. If Ventidius has decided that you and Salvidienus are to share, then you’ll continue to share for many moons. The only reason why Salvidienus hasn’t beaten the daylights out of you is because he doesn’t want to earn a reputation as a troublemaker before the campaign begins. Think about it, Maecenas,” said that persuasive voice. “Once we’ve seen action a couple of times, Salvidienus will stand even higher in Caesar’s estimation than he does now. Once that happens, he will beat the daylights out of you. Perhaps under your soft exterior, you are a military lion, but I doubt it.”

“What do you know? You’re only a boy!”

“True, but I don’t live in ignorance of what kind of general—or man—Caesar is. I was with him in Spain, you see.”

“A contubernalis!”

“Precisely. One who knows his place, what’s more. However, I’d like to see peace in our little corner of Caesar’s campaign, which means you and Salvidienus will have to learn to get along. Salvidienus matters to us. You’re a pampered snob,” Octavius said genially, “but for some reason, I’ve taken a fancy to you.” He waved his hand at the hundreds of scrolls. “What I see is a man of letters, not of the sword. If you take my advice, you’ll apply to Caesar when he arrives for a position as one of his personal assistants on the secretarial front. Gaius Trebatius isn’t with him, so there’s scope for you to advance that public career as a man of letters with Caesar’s help.”

“Who are you?” Maecenas asked hollowly.

“A friend,” Octavius said with a smile, and got up. “Think about what I’ve said, it’s good advice. Don’t let your wealth and education prejudice you against men like Salvidienus. Rome needs all kinds of men, and it’s to Rome’s advantage if different kinds of men tolerate one another’s quirks and dispositions. Send all of this except your literature back to Arretium, give Salvidienus half of your quarters, and don’t live like a sybarite in Caesar’s army. He’s not quite as strict as Gaius Marius, but he’s strict.”

A nod, and he was gone.

When Maecenas got his breath back, he stared at his furniture through a veil of tears. Several fell when his eyes reached his big, comfortable bed, but Gaius Maecenas was no fool. The lovely lad had exuded a strange authority. No arrogance, no hauteur, no coldness. Nor the slightest hint of an invitation, though Octavius had revealed a degree of perception about behavior that must surely have informed him that Gaius Maecenas, lover of women, was also a lover of men. He hadn’t referred to this by word or look, but he definitely understood that the principal reason Maecenas had tried to eject Salvidienus lay in a need for privacy above and beyond mere literary pursuits. Well, on this campaign it would have to be women, none but women.

So when Salvidienus returned several hours later, he found the room stripped of its trappings, and Gaius Maecenas seated at a plain folding table, his ample behind on a folding stool.

Out came a manicured hand. “I apologize, my dear Quintus Salvidienus,” said Maecenas. “If we’re to live together for many moons, then we’d best learn to get along. I’m soft, but I’m not a fool. If I annoy you, tell me. I’ll do the same.”

“I accept your apology,” said Salvidienus, who understood a few things about behavior too. “Octavius visited, did he?”

“Who is he?” Maecenas asked.

“Caesar’s nephew. Have you been issued orders?”

“Oh, no,” said Maecenas. “That’s not his style.”

The fact that Caesar didn’t arrive in Apollonia toward the end of March was generally blamed on the equinoctial gales, now blowing fitfully. Stuck in Brundisium, was the consensus.

On the Kalends of April, Ventidius sent for Gaius Octavius.

“This just came for you by special courier,” he said, his tone disapproving; in Ventidius’s catalogue of priorities, mere cadets didn’t receive specially couriered letters.

Octavius took the scroll, which bore Philippus’s seal, with a stab of alarm that had nothing to do with his mother or his sister. White-faced, he sank without permission into a chair to one side of Ventidius’s desk and gazed at the trusty muleteer, a helpless agony in his eyes that silenced Ventidius’s tongue.

“I’m sorry, my knees have gone,” he said, and wet his lips. “May I open this now, Publius Ventidius?”

“Go ahead. It’s probably nothing,” Ventidius said gruffly.

“No, it’s bad news about Caesar.” Octavius broke the seal, unfurled the single sheet, and read it laboriously. Finished, he didn’t look up, just thrust the paper across the desk. “Caesar is dead, assassinated.”

He knew before he opened it! thought Ventidius, snatching the letter. Having mumbled his way through it in disbelief, he stared at its recipient in numbed horror. “But why to you, news like this? And how did you know? Are you prescient?”

“Never before, Publius Ventidius. I don’t know how I knew.”

“Oh, Jupiter! What will happen to us now? And why hasn’t this news been conveyed to me or Rabirius Postumus?” Tears gathered in the muleteer’s eyes; he put his face upon his arms and wept bitterly.

Octavius got to his feet, his breath suddenly whistling. “I must return to Italy. My stepfather says he’ll be waiting for me in Brundisium. I’m sorry that the news came to me first, but perhaps the official notification was delayed by events.”

“Caesar dead!” came Ventidius’s muffled voice. “Caesar dead! The world has ended.”

Octavius left the office and the building, went down to the quays to hire a pinnace, laboring over the short walk as he hadn’t labored for months. Come, Octavius, you can’t suffer an attack of the asthma now! Caesar is dead, and the world is ending. I must know it all as soon as possible, I can’t lie here in Apollonia gasping for every breath.

“I’m for Brundisium today,” he told Agrippa, Salvidienus and Maecenas an hour later. “Caesar has been assassinated. Whoever wants to come with me is welcome, I’ve hired a big enough pinnace. There won’t be any expedition to Syria.”

“I’ll come with you,” Agrippa said instantly, and left the common room to pack his single trunk, call his single servant.

“Maecenas and I can’t just leave,” said Salvidienus. “We’ll have work to do if the army is to be stood down. Perhaps we’ll meet again in Rome.”

Salvidienus and Maecenas stared at Octavius as if at a total stranger; he had walked in looking blue around the mouth and wheezing, but absolutely calm.

“I haven’t time to deal with Epidius and my other tutors,” he said now, producing a fat purse. “Here, Maecenas, give this to Epidius and tell him to get everybody and everything to Rome.”

“There’s a gale coming,” Maecenas said anxiously.

“Gales never stopped Caesar. Why should they stop me?”

“You’re not well,” Maecenas said courageously, “that’s why.”

“Whether I’m on the Adriatic or in Apollonia, I won’t be well, but sickness wouldn’t stop Caesar, and it isn’t going to stop me.”

He went off to supervise the packing of his trunk, leaving Salvidienus and Maecenas to look at each other.

“He’s too calm,” said Maecenas.

“Maybe,” Salvidienus said pensively, “there’s more of his uncle in him than meets the eye.”

“Oh, I’ve known that since the moment I met him. But he does a balancing act on a nervous tightrope that nothing in the history books says Caesar did. The history books! How terrible, Quintus, to think he’s now relegated to the history books.”

“You’re not well,” said Agrippa as they walked down to the quays in the teeth of a rising wind.

“That subject is forbidden. I have you, and you’re enough.”

“Who would dare to murder Caesar?”

“The heirs of Bibulus, Cato and the boni, I imagine. They won’t go unpunished.” His voice dropped until it became inaudible to Agrippa. “By Sol Indiges, Tellus and Liber Pater, I swear that I will exact retribution!”

The open boat put out into a heaving sea, and Agrippa found himself Octavius’s nursemaid, for Scylax the body servant Octavius chose to go with him succumbed to seasickness even faster than his master did. As far as Agrippa was concerned, Scylax could die, but that couldn’t be Octavius’s fate. Between his shivering bouts of retching and an attack of the asthma that had him greyish-purple in the face, it did look to the worried Agrippa as if his friend might die, but they had no alternative save to go westward for Italy; wind and sea insisted upon pushing them in that direction. Not that Octavius was a troublesome or demanding patient. He simply lay in the bottom of the boat on a board to keep him clear of the foul water slopping there; the most Agrippa could do for him was to keep his chin up and his head to one side so that he couldn’t aspirate the almost clear fluid he vomited.

Agrippa now discovered convictions in himself that he hadn’t known he possessed: that this sickly fellow scant months younger than he wasn’t going to die, or disappear into obscurity now that his all-powerful uncle was no longer there to push him upward. At some point in the distant future, Octavius was going to matter to Rome, when he had grown to maturity and could emulate the earlier members of his family by entering the Senate. He will need military men like Salvidienus and me, he will need a paper man like Maecenas, and we must be there for him, despite whatever happens during the years that must elapse between now and when Gaius Octavius comes into his own. Maecenas is too exalted to be a client, but as soon as Octavius improves, I am going to ask him if I may become his first client, and advise Salvidienus to be his second client.

When Octavius fought to sit upright, Agrippa took him into his arms and held him where his feeble gestures indicated that he could breathe easiest, a sagum sheltering him from the rain and spume. At least, thought Agrippa, it’s not going to be a long passage. We’ll be in Italy before we know it, and once we’re on dry land he’s bound to lose the seasickness, if not the asthma. Whoever heard of something called asthma?

But landfall when it came was a bitter disappointment; the storm had blown them to Barium, sixty miles north of Brundisium.

In charge of Octavius’s purse—as well, for he had no money of his own—Agrippa paid the pinnace owner and carried his friend ashore, leaving Scylax to totter in his wake supported by his own man, Phormion, who to Agrippa represented the difference between utter penury and some pretensions to gentility.

“We must hire two gigs and get to Brundisium at once,” said Octavius, who looked much better just for leaving the sea.

“Tomorrow,” said Agrippa firmly.

“It’s barely dawn. Today, Agrippa, and no arguments.”

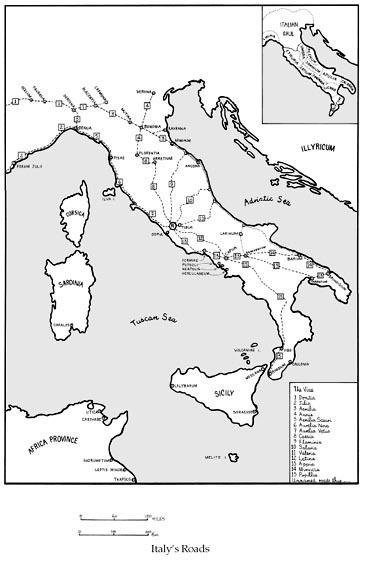

The asthma improved only a little on the journey, over the sealed Via Minucia but behind two molting mules, but Octavius refused to stop for longer than it took to change teams; they reached the house of Aulus Plautius on nightfall.

“Philippus couldn’t come, he has to stay closer to Rome,” Plautius said, showing Agrippa where to put Octavius, “but he’s sent a letter at the gallop, and there’s one from Atia too.”

Breathing easier with each passing moment, Octavius lay propped on pillows on a comfortable couch and extended his hand to the anxious Agrippa.

“You see?” he asked, his smile as beautiful as Caesar’s. “I knew I’d be safe with Marcus Agrippa. Thank you.”

“When did you last eat?” asked Plautius.

“In Apollonia,” said the famished Agrippa.

“Where are my letters?” Octavius demanded, more interested in reading than eating.

“Hand them over for the sake of peace,” Agrippa said, used to him. “He can read and eat at the same time.”

Philippus’s letter was longer than the brief note sent to Apollonia, and included a full list of the Liberators as well as the news that Caesar had named Gaius Octavius as his heir, and had also adopted him in his will.

I cannot understand Antonius’s toleration of these loathsome men, let alone what seems to be implied approval of their act. They have been granted a general amnesty, and though Brutus and Cassius have not yet appeared on their tribunals to resume their praetorian duties, it is being said that they will do this very shortly. Indeed, I imagine that they would already be back at work, had it not been for the advent of a fellow who appeared three days ago at the spot where Caesar’s body was summarily burned. He calls himself Gaius Amatius, and insists that he is Gaius Marius’s grandson. Certainly he has considerable oratorical skill, which argues against a purely peasant origin.

First he informed the crowds—they continue to gather every day in the Forum—that the Liberators are utter villains, and must be killed. His anger is directed at Brutus, Cassius and Decimus Brutus more than at the others, though my own opinion is that Gaius Trebonius is the biggest villain. He didn’t participate in the actual murder, but he masterminded the plot. On that first day Amatius inspired the crowd to anger: it began, as happened at the funeral, to howl for Liberator blood. His second appearance was even more effective, and the crowd grew really ugly.

But yesterday’s appearance, Amatius’s third, was worse. He accused Marcus Antonius of complicity in the deed! Said that Antonius’s accommodation of the Liberators (oddly enough, Antonius did use the word “accommodation”) was deliberate. Antonius was publicly patting the Liberators on the back, rewarding them. They walk around as free as birds, yet they murdered Caesar—Antonius was thick as thieves with Brutus and Cassius, hadn’t the people seen that for themselves? All this, and more. So the crowd grew riotous.

I am leaving for my villa at Neapolis, where I will meet you, but I have just heard that some of the Liberators have decided since the appearance of this Gaius Amatius to leave Italy. Cimber has gone to his province in a huge hurry, so have Staius Murcus, Trebonius and Decimus Brutus.

The Senate met to discuss the provinces, and Brutus and Cassius attended, expecting to hear where they would be sent to govern next year. Instead, Antonius discussed only his province, Macedonia, and Dolabella’s province, Syria. No talk of pursuing Caesar’s war against the Parthians, however. Antonius has laid claim to the six crack legions encamped in western Macedonia, insists they are now his. For war against Burebistas and the Dacians? He didn’t say so. I think he is simply ensuring his own survival if things come to yet another civil war. No decisions were taken about the other nine legions, which have not been recalled to Italy.

The Senate, aided and abetted by Cicero—who was back in the House the moment Caesar died, praising the Liberators to the skies—is busy starting to unravel Caesar’s laws, which is a tragedy. There’s no thought behind it. They remind me of a child getting its hands on mama’s sewing halfway through shaping a sleeve.

One other subject I must mention before closing—your inheritance. Octavius, I beg you not to take it up! Come to an agreement with the one-eighth heirs whereby the estate is more equitably split up, and decline to be adopted. To take up your inheritance is to court death. Between Antonius, the Liberators and Dolabella, you won’t live out the year. They will crush you, an eighteen-year-old. Antonius is beside himself with rage at being cut out of the will, especially by a mere lad. I do not say he did conspire with Caesar’s assassins, for there is no proof of it, but I do say that he has few scruples and no ethics. So when I see you, I will expect to hear you say that you have decided to decline Caesar’s bequest. Live to be an old man, Octavius.

Octavius put the letter down, chewing hungrily on a chicken leg. Thank all the gods, the asthma was lifting at last. He felt curiously invigorated, able to deal with anything.

“I am Caesar’s heir,” he said to Plautius and Agrippa.

Working his way through the very generous meal as if it were his last, Agrippa paused, the eyes beneath that jutting, thick-browed forehead gleaming. Plautius, who evidently knew this already, looked grim.

“Caesar’s heir,” said Agrippa. “What exactly does that mean?”

“It means,” Plautius answered, “that Gaius Octavius inherits all Caesar’s money and estates, that he will be rich beyond any imagination. But Marcus Antonius expected to inherit, and isn’t pleased.”

“Caesar also adopted me. I am no longer Gaius Octavius, I am Gaius Julius Caesar Filius.” As he announced this, Octavius seemed to swell, his grey eyes as brilliant as his smile. “What Plautius didn’t say was that, as Caesar’s son, I inherit his enormous clout—and his clientele. I will have at least a quarter of Italy as my clients—my legal followers, pledged to do my bidding—and almost everyone in Italian Gaul, because Caesar absorbed all Pompeius Magnus’s clients there as well as having multitudes of his own.”

“Which is why your stepfather doesn’t want you to take up this terrible inheritance!” Plautius cried.

“But you will,” Agrippa said, grinning.

“Of course I will. Caesar trusted me, Agrippa! In giving me his name, Caesar said that he thinks I have the strength and the spirit to continue his struggle to put Rome on her feet. He knew that I don’t have the ability to inherit his military mantle, but that didn’t matter as much to him as Rome does.”

“It’s a death sentence.” Plautius groaned.

“The name Caesar will never die, I will make sure of that.”

“Don’t, Octavius!” Plautius implored. “Please don’t!”

“Caesar trusted me,” Octavius repeated. “How can I betray that trust? If he were my age and this was given to him to do, would he abrogate it? No! And nor will I.”

Caesar’s heir broke the seal on his mother’s letter, glanced at it, tossed it into the brazier. “Silly,” he said, and sighed. “But then, she always is.”

“I take she’s begging you not to take up your inheritance either?” asked Agrippa, back into the food.

“She wants a living son, she says. Pah! I do not intend to die, Agrippa, no matter how much Antonius might want me to. Though why he should, I have no idea. No matter how the estate’s divided, he’s not an heir. Maybe,” Octavius went on, “we wrong Antonius. Perhaps his chief desire isn’t Caesar’s money, but Caesar’s clout and clientele.”

“If you don’t intend to die, then eat,” said Agrippa. “Go on, Caesar, eat! You’re not a tough, stringy old bird like your namesake, and you’ve nothing in your stomach at all. Eat!”

“You can’t call him Caesar!” Plautius bleated. “Even if he is adopted, his name becomes Caesar Octavianus, not plain Caesar.”

“I’m going to call him Caesar,” said Agrippa.

“And I will never, never forget that the first person to call me Caesar was Marcus Agrippa,” the debatably named heir said, gaze soft. “Will you cleave to me through thick and thin?”

Agrippa took the outstretched hand. “I will, Caesar.”

“Then you will rise with me. So I pledge it. You will be famous and powerful, have your pick of Rome’s daughters.”

“You’re both too young to know what you’re doing!” Plautius moaned, wringing his hands.

“We’re not, you know,” said Agrippa. “I think Caesar knew what he was doing too. He chose his heir wisely.”

Because Agrippa was right, Octavian* ate, his mind putting aside this extraordinary fate in favor of a more immediate and pressing concern: his asthma. Again, Caesar had come to his rescue in providing Hapd’efan’e, who had explained his malady to him in simple yet unoptimistic terms. Something no physician had done before. If he was in truth to survive, then he must follow Hapd’efan’e’s advice in all ways, from avoiding foods like honey and strawberries to disciplining his emotions into positive channels. Dust, pollen, chaff and animal hair would always be hazards, there was nothing he could do about those beyond try to avoid them, and that wouldn’t always be possible. Nor would he ever be a good sailor, between the heavy air and the seasickness. What he had to banish was fear, not easy for one whose mother had inculcated it in him so firmly. Caesar’s heir should know no fear, just as Caesar had known no fear. How can I assume Caesar’s name and massive dignitas if I stand there in public whistling like a bellows and blue in the face? I will conquer this handicap, because I must. Exercise, Hapd’efan’e had said. Good food. And a placid frame of mind. How can the owner of Caesar’s name have a placid frame of mind?

Very tired, he slept dreamlessly from just after that late dinner until two hours before dawn, not sorry that Plautius’s spacious house permitted him and Agrippa to have separate rooms. When he woke, he felt well and breathed easily. A drumming sound brought him to the window, where he found Brundisium in the grasp of driving rain; a glance up at the faint outline of the clouds ascertained that they were ragged, scudding before a high wind. There would be nobody on the streets today, for this weather had set in. Nobody on the streets today…

An idle thought, it wandered aimlessly through his mind and bumped into a fact he hadn’t remembered until the two collided. From what Plautius had said, all of Brundisium knew that he was Caesar’s heir, just like the rest of Italy. The news of Caesar’s death had spread like wildfire, so the news of Caesar’s heir, this eighteen-year-old nephew (he would forget the “great”), had gone after it with equal speed. That meant that whenever he showed his face, people would defer to him, especially if he announced himself as Gaius Julius Caesar. Well, he was Gaius Julius Caesar! He would never again call himself anything else, save perhaps to tack “Filius” on to it. As for the Octavianus—a useful way to tell friend from enemy. Those who called him Octavianus would be those who refused to acknowledge his special status.

He remained at the window watching the thick rods of rain angle down before the wind, his face, even his eyes, composed into a tranquil mask that gave nothing of his thoughts away. Inside that bulbous cranium—the same huge skull Caesar and Cicero both owned—his thoughts were very busy, but not tumultuous. Marcus Antonius was desperate for money, and there would be none from Caesar. The contents of the Treasury were probably fairly safe, but right next door in the vaults of Gaius Oppius, chief banker to Brundisium and one of Caesar’s loyalest adherents, lay a vast sum of money. Caesar’s war chest. Possibly in the neighborhood of thirty thousand talents of silver, from what Caesar had said—take it all with you, don’t rely on sending back to the Senate for more because you mightn’t get it. Thirty thousand talents amounted to seven hundred and fifty million sesterces.

How many talents can one of those massive wagons I saw in Spain carry if it’s drawn by ten oxen? These will be Caesar’s wagons here too—the very best from axle grease to stout, iron-bound Gallic wheels. Could one wagon carry three, four, five hundred talents? Now that’s the kind of thing Caesar would know at once, but I do not. How fast does a groaning wagon travel?

First I have to get the war chest out of the vaults. How? Unabashed. Just walk in and ask for it. After all, I am Gaius Julius Caesar! I have to do this. Yes, I must do this! But even supposing I managed to spirit it away, where to hide it? That’s easy—on my own estates beyond Sulmo, estates my grandfather had as spoils from the Italian War. Useful only for the timber they bear, logged and sent to Ancona for export. So cover the silver with a layer of wooden planks. I have to do this! I must!

Holding a lamp, he went to Agrippa’s room and woke him. A true warrior, Agrippa slept like the dead, yet was fully alert at a soft word.

“Get up, I need you.”

Agrippa slipped a tunic over his head, ran a comb through his hair, bent to lace on boots, grimacing at the sound of rain.

“How many talents can a heavy army wagon carry, and how many oxen are needed to pull it?” asked Octavian.

“One of Caesar’s wagons, at least a hundred with ten oxen, but a lot depends on how the load is distributed—the smaller and more uniform the components, the heavier the cargo can be. Roads and terrain are factors too. If I knew what you were after, Caesar, I could tell you more.”

“Are there any wagons and teams in Brundisium?”

“Bound to be. The heavy baggage is still in transit.”

“Of course!” Octavian slapped his thigh in vexation at his own density. “Caesar would have conveyed the war chest from Rome in person, it’s still here because he’ll take it on in person, so the wagons and oxen are here too. Find them for me, Agrippa.”

“Am I allowed to ask what and why?”

“I’m appropriating the war chest before Antonius can get his hands on it. It’s Rome’s money, but Antonius would use it to pay his debts and run up more. When you find the teams and wagons, bring them into Brundisium in a single line, then dismiss their drivers. We’ll hire others after they’re loaded. Park the leading one outside Oppius’s bank next door. I’ll organize the labor,” said Octavian briskly. “Pretend you’re Caesar’s quaestor.”

Agrippa departed wrapped in his waterproof circular cape, and Octavian went to break his fast with Aulus Plautius.

“Marcus Agrippa has gone out,” he said, looking very ill.

“In this weather?” Plautius asked, then sniffed. “Looking for a whorehouse, no doubt. I hope you have more sense!”

“As if asthma were not enough, Aulus Plautius, I feel a sick headache coming on, so it’s bed for me in absolute silence. I’m sorry I won’t be able to keep you company on such an awful day.”

“Oh, I shall curl up on my study couch and read a book, which is why I’ve sent my wife and children to my estates—peace and quiet to read. I intend to best Lucius Piso—oh, you’ve eaten nothing!” cried Plautius, clucking. “Off you go, Octavius.”

Off the young man went, into the rain. The living rooms opened on to the back lane to avoid the noise of wagons rumbling up and down the main street; if Plautius became immersed in his book, he’d hear nothing. Fortuna is my partner in this enterprise, thought Octavian; the weather is perfect for this, and the Lady of Good Luck loves me, she will see me through. Brundisium is used to strings of wagons and moving armies.

* * *

Two cohorts of troops were camped in a field on the outskirts of the city, all veterans not yet incorporated into legions, having enlisted too late or come too far to reach Capua before the legions left. Whatever military tribune was in charge of them had abandoned them to their own devices, which in weather like this consisted of dice, knucklebones, board games and talk; wine was off legionary menus since the Tenth and Twelfth had mutinied. These men, who had belonged to the old Thirteenth, had no sympathy with mutiny and had only enlisted again because they loved Caesar and fancied a good long campaign against the Parthians. Having heard of his awful death, they grieved, and wondered what was going to happen to them now.

No expert on legionary dispositions, the rather small, hooded and caped visitor had to enquire of the sentries whereabouts the primipilus centurion lived, then trudged down the rows of wooden huts to knock on the door of a somewhat larger structure. The noise of voices inside ceased; the door opened. Octavian found himself looking up at a tall, burly fellow who wore a red, padded tunic. Eleven other men sat around a table, all in the same gear, which meant that the visitor surveyed the entire centurion complement of two cohorts.

“Shocking weather,” said the door opener. “Marcus Coponius at your service.”

Engaged in doffing his sagum, Octavian didn’t reply until he was done, then stood in his trim leather cuirass and kilt, mop of golden hair damp but not wringing wet. There was something about him that brought the eleven other centurions to their feet, quite why they didn’t know.

“I’m Caesar’s heir, so my name is Gaius Julius Caesar,” said Octavian, big grey eyes welcoming their hard-bitten faces, a smile on his lips that was hauntingly familiar. A collective gasp went up, the men stiffened to attention.

“Jupiter! You look just like him!” Coponius breathed.

“A smaller edition,” Octavian said ruefully, “but I hope I still have some growing to do.”

“Oh, it’s terrible, terrible!” said one at the table, tears gathering. “What will we do without him?”

“Our duty to Rome,” said Octavian, matter-of-fact. “That’s why I’m here, to ask you to do a duty for Rome.”

“Anything, young Caesar, anything,” said Coponius.

“I have to get the war chest out of Brundisium as soon as I possibly can. There won’t be any campaign to Syria, I’m sure you realize that, but so far the consuls haven’t indicated what’s going to happen to the legions over the waves in Macedonia—or men like you, still waiting to be shipped. My job is to collect the war chest on behalf of Rome. My adjutant, Marcus Agrippa, is rounding up the wagons and oxen that carry the war chest, but I need loading labor, and I don’t trust civilians. Will your men put the money on board the wagons for me?”

“Oh, gladly, young Caesar, gladly! There’s nothing worse than wet weather without no work to do.”

“That’s very kind of you,” said Octavian with the smile so reminiscent of Caesar’s. “I’m the closest thing Brundisium has to a commanding officer at the moment, but I wouldn’t like you to think that I have imperium, because I don’t. Therefore I ask humbly, I don’t command that you help me.”

“If Caesar made you his heir, young Caesar, and gave you his name, there’s no need to command,” said Marcus Coponius.

With a thousand men at his beck and call, many more than one of the sixty wagons were loaded simultaneously. Caesar had devised a knacky way to carry his money—it was money, not unminted sows. Each talent, in the form of 6,250 denarii, was stored in a canvas bag equipped with two handles, so that two soldiers could easily carry a one-talent bag between them. Swiftly loading while the rain poured down unabated and all Brundisium remained indoors, even on this usually busy street, the wagons moved onward steadily to a timber yard where sawn planks were carefully placed over the bags to look as if sawn planks were all the wagons carried.

“It’s sensible,” said Octavian glibly to Coponius, “to disguise the cargo, because I don’t have the imperium to order a military escort. My adjutant is hiring drivers, but we won’t let them know what we’re really hauling, so they won’t get here until after you’re gone.” He pointed to a hand cart that held a number of smaller linen bags. “This is for you and your men, Coponius, as a token of my thanks. If you spend any of it on wine, be discreet. If Caesar can help you in any way in the future, don’t hesitate to ask.”

So the thousand soldiers pushed the hand cart back to their camp, there to discover that Caesar’s heir had gifted them with two hundred and fifty denarii for each ranker, one thousand for each centurion, and two thousand for Marcus Coponius. The unit for accounting was the sestertius, but the denarius was far more convenient to mint, at four sesterces to the denarius.

“Did you believe all that, Coponius?” asked one of the very gratified centurions.

Coponius eyed him in scorn. “What d’you take me for, an Apulian hayseed? I don’t have no idea what young Caesar’s up to, but he’s his tata’s son, that’s for sure. A thousand miles ahead of the opposition. And whatever he’s up to ain’t none of our business. We’re Caesar’s veterans. As far as I’m concerned, for one, anything young Caesar does is all right.” He put his right index finger to the side of his nose and winked. “Mum’s the word, boys. If someone comes asking, we don’t know nothing, because we was never out in the rain.”

Eleven heads nodded complete agreement.

So the sixty wagons rolled out in the pouring rain on the deserted Via Minucia almost to Barium, then set off cross-country on hard, stony ground toward Larinum, with Marcus Agrippa in civilian dress shepherding this precious load of timber planks. The drivers, who walked alongside their leading beasts rather than sat holding reins, were being paid very well, but not so excessively that they were curious; they were simply glad for the work at this slack season. Brundisium was the busiest harbor in all Italy, cargo and armies came and went incessantly.

Octavian left Brundisium a full nundinum later and took the Via Minucia to Barium. There he left it to join the wagons, still plodding north in the direction of Larinum at surprising speed considering that they hadn’t used a road since before Barium. When he found them, he learned that Agrippa had been pushing them along while ever there was a moon to see by, as well as all day.

“It’s flat ground without hazards. It won’t be so easy once we get into the mountains,” Agrippa said.

“Then follow the coast, don’t turn inland until you see an unsealed road ten miles south of the road to Sulmo. You’ll be safe enough on that road, but don’t use any others. I’m going ahead to my lands to make sure there are no chattering locals and a good but accessible hiding place.”

Luckily chattering locals were few and far between, for the estate was forest in a land of forests. Having discovered that Quintus Nonius, his father’s manager, still occupied the staff quarters of the comfortable villa where Atia used to bring her ailing son for a summer in mountain air, Octavian decided that the wagons would be safe in a clearing several miles beyond the villa. Logging, said Nonius, was going on in a different area, and people didn’t prowl; there were too many bears and wolves.

Even here, Octavian was astonished to learn, people already knew that Caesar was dead and that Gaius Octavius was Caesar’s heir. A fact that delighted Nonius, who had loved the quiet, sick little boy and his anxious mother. However, few if any of the locals knew who owned these timber estates, still referred to as “Papius’s place” after their original Italian owner.

“The wagons belong to Caesar, but people who aren’t entitled to them will be looking for them everywhere, so no one must know that they’re here on Papius’s place,” he explained to Nonius. “From time to time I may send Marcus Agrippa—you’ll meet him when the wagons arrive—to pick up one or two of them. Dispose of the oxen as you think best, but always have twenty beasts on hand. Luckily you use oxen to tow logs to Ancona, so the presence of oxen won’t seem unusual. It’s important, Nonius—so important that my life may depend upon your and your family’s silence.”

“Don’t you worry, little Gaius,” said the old retainer. “I’ll look after everything.”

Convinced that Nonius would, Octavian backtracked to the junction of the Via Minucia and the Via Appia at Beneventum, picked up the Via Appia there and resumed his journey to Neapolis, where he arrived toward the end of April to find Philippus and his mother in a fever of worry.

“Where have you been?” Atia cried, hugging him to her and watering his tunic with tears.

“Laid low with asthma in some mean inn on the Via Minucia,” Octavian explained, removing himself from his mother’s clutches, feeling an irritation he was at some pains to hide. “No, no, leave me be, I’m well now. Philippus, tell me what’s happened, I’ve had no news since your letter to Brundisium.”

Philippus led the way to his study. A man of high coloring and considerable good looks, he seemed to his stepson’s eyes to have aged a great deal in two months. Caesar’s death had hit him hard, not least because, like Lucius Piso, Servius Sulpicius and several others among the thin ranks of the consulars, Philippus was trying to steer a middle course that would ensure his own survival no matter what happened.

“Gaius Marius’s so-called grandson, Amatius?” Octavian asked.

“Dead,” said Philippus, grimacing. “On his fourth day in the Forum, Antonius and a century of Lepidus’s troops arrived to listen. Amatius pointed at him and screamed that there stood the real murderer of Caesar, whereupon the troops took Amatius into custody and marched him off to the Tullianum.” Philippus shrugged. “Amatius never emerged, so the crowd eventually went home. Antonius went straight to a meeting of the Senate in Castor’s, where Dolabella asked him what had happened to Amatius. ‘I executed him,’ said Antonius. Dolabella protested that the man was a Roman citizen and ought to have been tried, but Antonius said Amatius wasn’t a Roman, he was an escaped Greek slave named Hierophilus. And that was the end of it.”

“Which rather indicates what kind of government Rome has,” Octavian said thoughtfully. “Clearly it isn’t wise to accuse dear Marcus Antonius of anything.”

“So I think,” Philippus agreed, face grim. “Cassius tried to bring up the subject of the praetors’ provinces again, and was told to shut up. He and Brutus tried to occupy their tribunals several times, but desisted. Even after Amatius was executed, the crowd didn’t welcome them, though their amnesty holds up. Oh, and Marcus Lepidus is the new Pontifex Maximus.”

“They held an election?” Octavian asked, surprised.

“No. He was adlected by the other pontifices.”

“That’s illegal.”

“There’s no definition of legal anymore, Octavius.”

“My name isn’t Octavius, it’s Caesar.”

“That is still undecided.” Philippus got up, went to his desk and withdrew a small object from its drawer. “Here, this has to go to you—for the time being only, I hope.”

Octavian took it and turned it over between trembling hands, awed. A singularly beautiful seal ring consisting of a flawless, royally purple amethyst set in pink gold. It bore a delicately carved intaglio sphinx and the word CAESAR in mirrored capitals above the sphinx’s human head. He slipped it on to his ring finger, to find that it fitted perfectly. The bigger Caesar’s fingers had been slender, his own were shorter, thicker, more spatulate. A curious feeling, as if its weight and the essence of Caesar it had drawn into itself were suffusing into his own body.

“An omen! It might have been made for me.”

“It was made for Caesar—by Cleopatra, I believe.”

“And I am Caesar.”

“Defer that decision, Octavius!” Philippus snapped. “A tribune of the plebs—the assassin Gaius Casca—and the plebeian aedile Critonius took Caesar’s Forum statues from their plinths and pedestals and sent them to the Velabrum to be broken up. The crowd caught them at it, went to the sculptor’s yard and rescued them, even the two that had already been attacked with mallets. Then the crowd set fire to the place, and the fire spread into the Vicus Tuscus. A shocking conflagration! Half the Velabrum burned. Did the crowd care? No. The intact statues were put back, the two broken ones given to another sculptor to repair. Then the crowd started to roar, demanding that the consuls produce Amatius. Of course that wasn’t possible. A terrible riot erupted—the worst I ever remember. Several hundred citizens and fifty of Lepidus’s soldiers were killed before the mob was dispersed. A hundred of the rioters were taken prisoner, divided into citizens and non-citizens, then the citizens were thrown from the Tarpeian Rock, and the non-citizens were flogged and beheaded.”

“So to demand justice for Caesar is treason,” Octavian said, drawing in a breath. “Our Antonius is showing his true colors.”

“Oh, Octavius, he’s just a brute! I don’t think it occurs to him that some might interpret his actions as anti-Caesar. Look at what he did in the Forum when Dolabella was deploying his street gangs. Antonius’s answer to public violence is slaughter because it’s his nature to slaughter.”

“I think he’s aiming to take Caesar’s place.”

“I disagree. He abolished the office of dictator.”

“If ‘rex’ is a simple word, so too is ‘dictator.’ So I take it that no one dares to laud Caesar, even the crowd?”

Philippus laughed harshly. “Antonius and Dolabella should hope! No, nothing deters the common people. Dolabella had the altar and column removed from the place where Caesar burned when he discovered that people were openly calling Caesar ‘Divus Julius.’ Can you imagine that, Octavius? They started worshiping Caesar as a god before the very stones where he burned were cold!”

“Divus Julius,” Octavian said, smiling.

“A passing phase,” said Philippus, misliking that smile.

“Perhaps, but why can’t you see its significance, Philippus? The people have started worshiping Caesar as a god. The people! No one in government started it—in fact, everyone in government is doing his best to stamp it out. The people loved Caesar so much that they cannot bear to think of him gone, so they have resurrected him as a god—someone they can pray to, look to for consolation. Don’t you see? They’re telling Antonius, Dolabella and the Liberators—pah, how I hate that name!—and everyone else at the top of the Roman tree that they refuse to be parted from Caesar.”

“Don’t let it go to your head, Octavius.”

“My name is Caesar.”

“I will never call you that!”

“One day you will have no choice. Tell me what else goes on.”

“For what it’s worth, Antonius has betrothed his daughter by Antonia Hybrida to Lepidus’s eldest boy. As both children are years off marriageable age, I suspect it will last only as long as their fathers are holding each other’s pricks to piss. Lepidus went to govern Nearer Spain and Narbonese Gaul over two nundinae ago. Sextus Pompeius is now fielding six legions, so the consuls decided that Lepidus had better contain his Spanish province while he could. Pollio is still holding Further Spain in good order, so we hear. If we can believe what we hear.”

“And that wonderful pair, Brutus and Cassius?”

“Have quit Rome. Brutus has given the urban praetor’s duties to Gaius Antonius while he—er—recovers from severe emotional stress. Whereas Cassius can at least pretend to continue his foreign praetor’s duties as he wafts around Italy. Brutus took both Porcia and Servilia with him—I hear that the battles between the two women are Homeric—teeth, feet, nails. Cassius gave out that he needs to be nearer to his pregnant Tertulla in Antium, but no sooner did he leave Rome than Tertulla arrived back in Rome, so who knows what the true story is in that marriage?”

Octavian cast his stepfather an unsettlingly shrewd glance. “There’s trouble brewing all over the place and the consuls aren’t handling it skillfully, are they?”

A sigh from Philippus. “No, they’re not, boy. Though they’re getting along better together than any of us believed possible.”

“And the legions, with regard to Antonius?”

“Are being brought back from Macedonia gradually, I hear, apart from the six finest, which he’s keeping there for when he goes to govern. The veterans still waiting for their land in Campania are growing restless because the moment Caesar died—”

“—was murdered—” Octavian interrupted.

“—died, the land commissioners stopped allocating the parcels to the veterans and packed up their booths. Antonius has been obliged to go to Campania and get the land commissioners back to work. He’s still there. Dolabella is in charge of Rome.”

“And Caesar’s altar? Caesar’s column?”

“I told you, gone. Just where is your mind going, Octavius?”

“My name is Caesar.”

“Having heard all this, you still believe you’ll survive if you take up your inheritance?”

“Oh, yes. I have Caesar’s luck,” said Octavian with a very secretive smile. Enigmatic. If one’s seal ring bore a sphinx, to be an enigma was mandatory.

Octavian went to his old room to find that he had been promoted to a suite. Even if Philippus did intend to talk him out of taking up his inheritance, that arch-fence-sitter was clever enough to understand that one didn’t put Caesar’s heir in accommodations fit for the master’s stepson.

His thoughts were disciplined, even if they were fantastic. The rest of what Philippus had had to say was interesting, germane to how he conducted himself in the future, but paled before the story of Divus Julius. A new god apotheosized by the people of Rome for the people of Rome. In the face of obdurate opposition from the consuls Antonius and Dolabella, even at the cost of many lives, the people of Rome were insisting that they be allowed to worship Divus Julius. To Octavian, a beacon luring him on. To be Gaius Julius Caesar Filius was wonderful. But to be Gaius Julius Caesar Divi Filius—the son of a god—was miraculous.

But that is for the future. First, I must become known far and wide as Caesar’s son. Coponius the centurion said I was his image. I am not, I know that. But Coponius looked at me through the eyes of pure sentiment; the tough, aging man he had served under—and probably never seen at really close quarters—was golden-haired and light of eye, was handsome and imperious. What I have to do is convince people, including Rome’s soldiers, that when he was my age, Caesar looked just like me. I can’t cut my hair that short because my ears are definitely not Caesar’s, but the shape of my head is. I can learn to smile like him, walk like him, wave my hand exactly as he used to, radiate approachability and careless consciousness of my exalted birth. The ichor of Mars and Venus flows in my veins too.

But Caesar was very tall, and in my heart I know that I have scant growing left to do. Perhaps another inch or two, but that will still fall far short of his height. So I will wear boots with soles four inches thick, and to make the device look less obvious, they will always be proper boots, closed at the toe. At a distance, which is how the soldiers will see me, I will tower like Caesar—still not nearly as tall, but close enough to six feet. I will make sure that the men around me are all short. And if my own Class laughs, let them. I will eat the foods that Hapd’efan’e said elongate the bones—meat, cheese, eggs—and I will exercise by stretching. The high boots will be difficult to walk in, but they will give me an athletic gait because walking in them will require great skill. I will pad the shoulders of my tunics and cuirasses. It’s Caesar’s luck that Caesar was not a hulk like Antonius; all I have to be is an actor.

Antonius will try to block my inheriting. The lex curiata of adoption won’t come quickly or easily, but a law doesn’t really matter as long as I behave like Caesar’s heir. Behave like Caesar himself. And the money will be difficult to lay my hands on too because Antonius will block probate. I have plenty of my own, but I may need far more. How fortunate that I appropriated the war chest! I wonder when that oaf Antonius will remember that it exists, and send for it? Old Plautius lives in blissful ignorance, and while Oppius’s manager will say that Caesar’s heir collected it, I shall deny that. Protest that someone very clever impersonated me. After all, the appropriation happened the day after I arrived from Macedonia—how could I have done it so swiftly? Impossible! I mean, an eighteen-year-old think of something so audacious, so—breathtaking? Ha ha ha, what a laugh! I am an asthmatic, and I had a sick headache too.

Yes, I will feel my way and keep my counsel. Agrippa I can trust with my very life; Salvidienus and Maecenas, less so, but they’ll prove good helpmates as I tread this precarious path in my high-soled boots. First and foremost, emphasize the likeness to Caesar. Concentrate on that ahead of anything else. And wait for Fortuna to toss me my next opportunity. She will.

Philippus moved to his villa at Cumae, where the seemingly endless stream of visitors began, all anxious to see Caesar’s heir.

Lucius Cornelius Balbus Major came first, arrived convinced that the young man would not prove up to the task Caesar had given him, and departed in a very different frame of mind. The lad was as subtle as a Phoenician banker, and did have an uncanny look of Caesar despite the manifest discrepancies in features and stature. His fair brows were mobile in Caesar’s exact fashion, his mouth had the same humorous curve, his facial expressions echoed Caesar’s, so did the way his hands moved. His voice, which Balbus remembered as light, had deepened. The only concrete information Balbus prised out of him was that he definitely intended to be Caesar’s heir.

“I was fascinated,” Balbus said to his nephew and business partner, Balbus Minor. “He has his own style, yes, but he has all Caesar’s steel, never doubt it. I am going to back him.”

Next came Gaius Vibius Pansa and Aulus Hirtius, destined to be consuls next year if Antonius and Dolabella didn’t decide that Caesar’s appointments should be overturned. Knowing this, both were worried men. Both had met Octavian: Hirtius in Narbo, Pansa in Placentia. Neither had thought much about him, but now their eyes rested on him in puzzled wonder. Had he reminded them of Caesar then? He definitely did now. The trouble was that the living Caesar cast all others in the shade, and the contubernalis had been self-effacing. Hirtius ended in liking Octavian greatly; Pansa, remembering that dinner in Placentia, reserved judgement, convinced that Antonius would cut the boy’s ambitions to ribbons. Yet neither man thought Octavian afraid, and neither man thought that his lack of fear was due to ignorance of what lay in store. He had Caesar’s unswerving determination to see things through to the end, and seemed to contemplate his probable fate with a quite unyouthful equanimity.

Cicero’s villa, where Pansa and Hirtius were staying, was right next door. Octavian did not make the mistake of waiting for Cicero to call on him. He called on Cicero.

Who eyed him rather blankly, though the smile—oh, so like Caesar’s!—tugged at his heart. Caesar had possessed an irresistible smile, therefore resisting it had been a hard business. Whereas when it came from such an inoffensive, likeable boy as Gaius Octavius, he could respond to it without reserve.

“You are well, Marcus Cicero?” Octavian asked anxiously.

“I’ve been better, Gaius Octavius, but I’ve also been worse.” Cicero sighed, unable to discipline that treacherous tongue into silence. When one was born to talk, one would talk to a post, and Caesar’s heir was no post. “You’ve caught me in the midst of personal upheavals as well as upheavals of the state. My brother, Quintus, has just divorced Pomponia, his wife of many years.”

“Oh, dear! Isn’t she Titus Atticus’s sister?”

“She is,” Cicero said sourly.

“Acrimonious, was it?” Octavian asked sympathetically.

“Dreadfully so. He can’t pay her dowry back.”

“I must offer my condolences for the death of Tullia.”

The brown eyes moistened, blinked. “Thank you, they are most welcome.” A breath quivered. “It seems half a lifetime ago.”

“Much has happened.”

“Indeed, indeed.” Cicero shot Octavian a wary look. “I must offer you condolences for Caesar’s death.”

“Thank you.”

“I never could like him, you know.”

“That’s understandable,” said Octavian gently.

“I couldn’t grieve at his death, it was too welcome.”

“You had no reason to feel otherwise.”

So when Octavian took himself off after a properly short visit, Cicero decided that he was charming, quite charming. Not at all what he had expected. Those beautiful grey eyes held no coldness or arrogance; they caressed. Yes, a very sweet, decently humble young fellow.

So when Octavian paid several more visits to Cicero, he was received warmly, allowed to sit and listen to the Great Advocate talk for some time on each occasion.

“I do believe,” Cicero said to his newly arrived houseguest, Lentulus Spinther Junior, “that the lad is really devoted to me.” He preened.

“Once we’re all back in Rome, I shall take Octavius under my wing. I—ah—hinted that I would, and he was enraptured. So different from Caesar! The only similarity I find is the smile, though I’ve heard others call him Caesar’s living image. Well, not everyone is gifted with my degree of perception, Spinther.”

“Everyone is saying that he means to take up his inheritance,” said Spinther.

“Oh, he will, no doubt about that. But it doesn’t worry me in the least—why should it?” Cicero asked, nibbling a candied fig. “Who inherits Caesar’s vast fortune and estates doesn’t matter a”—he brandished his snack—” fig. Who matters is the man who inherits Caesar’s far vaster army of clients. Do you honestly think that they will cleave to an eighteen-year-old as raw as freshly killed meat, as green as grass, as naive as an Apulian goatherd? Oh, I don’t say that young Octavius doesn’t have potential, but even I took some years to mature, and I was an acknowledged child prodigy.”

The acknowledged child prodigy was invited, together with Balbus Major, Hirtius and Pansa, to dinner at Philippus’s villa.

“I’m hoping that the four of you will support Atia and me in persuading Gaius Octavius to refuse his inheritance,” Philippus said as the meal began.

Though he itched to correct his stepfather, Octavian said nothing about wanting to be called Caesar; instead, he reclined in the most junior spot on the lectus imus and forced himself to eat fish, meat, eggs and cheese without saying anything at all unless asked. Of course he was asked; he was Caesar’s heir.

“You definitely shouldn’t,” said Balbus. “Too risky.”

“I agree,” said Pansa.

“And I,” said Hirtius.

“Listen to these august men, little Gaius,” Atia pleaded from the only chair. “Please listen!”

“Nonsense, Atia.” Cicero chuckled. “We may say what we like, but Gaius Octavius isn’t going to change his mind. It’s made up to accept your inheritance, correct?”

“Correct,” said Octavian placidly.

Atia got up and left, on the verge of tears.

“Antonius expects to inherit Caesar’s enormous clientele,” Balbus said in his lisping Latin. “That would have been automatic had he been named Caesar’s heir, but young Octavius here has—er—complicated the picture. Antonius must be offering to Fortuna in gratitude that Caesar didn’t name Decimus Brutus.”

“Quite so,” said Pansa. “By the time that you’re old enough to challenge Antonius, my dear Octavius, he’ll be past his prime.”

“Actually I’m rather surprised that Antonius hasn’t come to congratulate his young cousin,” Cicero said, diving into the mound of oysters that had been living in Baiae’s warm waters that dawn.

“He’s too busy sorting out the veterans’ land,” Hirtius said. “That’s why brother Gaius in Rome is enacting new agrarian laws. You know our Antonius—too impatient to wait for anything, so he’s decided to legislate reluctant sellers into giving up their land for the veterans. With little or no financial recompense.”

“That wasn’t Caesar’s way,” said Pansa, scowling.

“Oh, Caesar!” Cicero waved a dismissive hand. “The world has changed, Pansa, and Caesar is no longer in it, thank all the gods. One gathers that most of the silver in the Treasury went into Caesar’s war chest, and of course Antonius can’t touch the gold. There’s not the money for Caesar’s system of compensation, hence Antonius’s more draconian measures.”

“Why doesn’t Antonius repossess the war chest, then?” asked Octavian.

Balbus sniggered. “He’s probably forgotten it.”

“Then someone ought to remind him,” said Octavian.

“The tributes are due from the provinces,” Hirtius remarked. “I know Caesar was planning to use them to continue buying land. Don’t forget he levied huge fines on Republican cities. The next installments ought to be in Brundisium by now.”

“Antonius really ought to visit Brundisium,” said Octavian.

“Don’t worry your head about where Antonius is going to find money,” Cicero chided. “Fill it with rhetoric instead, Octavius. That’s the way to the consulship!”

Octavian flashed him a smile, resumed eating.

“At least we six here can console ourselves with the fact that none of us owns land between Teanum and the Volturnus River,” said Hirtius, who was amazingly knowledgeable about everything. “I gather that’s where Antonius is garnishing his land. Latifundia only, not vineyards.” He then proceeded to drop sensational news into the conversation. “Land, however, is the least of Antonius’s concerns. On the Kalends of June he intends to ask the House to let him swap Macedonia for two of the Gauls—Italian Gaul and Further Gaul excluding Lepidus’s Narbonese province, as Lepidus is to continue governing next year. It seems Pollio in Further Spain will also continue next year, whereas Plancus and Decimus Brutus are to be required to step down.” Discovering every eye fixed on him in horror, Hirtius made things even worse. “He is also going to ask the House to let him keep those six crack legions in Macedonia, but ship them to Italy in June.”

“This means Antonius doesn’t trust Brutus and Cassius,” said Philippus slowly. “I admit they’ve issued edicta saying they did Rome and Italy a great service in killing Caesar, and begging the Italian communities to support them, but if I were Antonius, I’d be more afraid of Decimus Brutus in Italian Gaul.”

“Antonius,” said Pansa, “is afraid of everybody.”

“Oh, ye gods!” cried Cicero, face paling. “This is idiocy! I can’t speak so certainly for Decimus Brutus, but I know that Brutus and Cassius don’t even dream of raising rebellion against the present Senate and People of Rome! I mean, I myself am back in the Senate, which shows everybody that I support this present government! Brutus and Cassius are patriots to the core! They would never, never, never incite an uprising in Italy!”

“I agree,” said Octavian unexpectedly.

“Then what’s going to happen to the campaign with Vatinius against Burebistas and his Dacians?” asked Philippus.

“Oh, that died with Caesar,” said Balbus cynically.

“Then by rights Dolabella ought to have the best legions for Syria—in fact, they’re needed there now,” said Pansa.

“Antonius is determined to have the six best right here on Italian soil,” said Hirtius.

“To achieve what?” Cicero demanded, grey and sweating.

“To protect himself against anyone who tries to tear him off his pedestal,” said Hirtius. “You’re probably right, Philippus—the trouble when it comes will be from Decimus Brutus in Italian Gaul. All he has to do is find some legions.”

“Oh, will we never be rid of civil war?” cried Cicero.

“We were rid of it until Caesar was murdered,” Octavian said dryly. “That’s inarguable. But now that Caesar’s dead, the leadership is in flux.”

Cicero frowned; the boy had clearly said “murdered.”

“At least,” Octavian continued, “the foreign queen and her son are gone, I hear.”

“And good riddance!” Cicero snapped savagely. “It was she who filled Caesar’s head with ideas of kingship! She probably drugged him too—he was always drinking some medicine that shifty Egyptian physician concocted.”

“What she couldn’t have done,” said Octavian, “was inspire the common people to worship Caesar as a god. They thought of that for themselves.”

The other men stirred uneasily.

“Dolabella put paid to that,” Hirtius said, “when he took the altar and column away.” He laughed. “Then hedged his bets! He didn’t destroy them, he popped them into storage. True!”

“Is there anything you don’t know, Aulus Hirtius?” Octavian asked, laughing too.

“I’m a writer, Octavianus, and writers have a natural tendency to listen to everything from gossip to prognostication. And consuls musing on the state of affairs.” Then he dropped another piece of shocking news. “I also hear that Antonius is legislating the full citizenship for all of Sicily.”

“Then he’s taken a massive bribe!” Cicero snarled. “Oh, I begin to dislike this—this monster more and more!”

“I can’t vouch for a Sicilian bribe,” Hirtius said, grinning, “but I do know that King Deiotarus has offered the consuls a bribe to return Galatia to its pre-Caesar size. As yet they haven’t said yes or no.”

“To give Sicily the full citizenship endows a man with a whole country of clients,” Octavian said thoughtfully. “As I am a mere youth, I have no idea what Antonius plans, but I do see that he’s giving himself a lovely present—the votes of our closest grain province.”

Octavian’s servant Scylax entered, bowed to the diners, then moved deferentially to his master’s side. “Caesar,” he said, “your mother is asking for you urgently.”

“Caesar?” asked Balbus, sitting up quickly as Octavian left.

“Oh, all his servants call him Caesar,” Philippus growled. “Atia and I have talked ourselves hoarse, but he insists upon it. Haven’t you noticed? He listens, he nods, he smiles sweetly, and then he does precisely what he meant to do anyway.”

“I am just profoundly grateful,” Cicero said, suppressing his un-ease at hearing this about Octavius, “that the lad has you to guide him, Philippus. I confess that when I first heard that Octavius had returned to Italy so quickly after Caesar’s death, I thought immediately what a convenient rallying point he’d make for a man intent upon overthrowing the state. However, now that I’ve actually met him, I don’t fear that at all. He’s delightfully humble, yes, but not fool enough to allow himself to be used as somebody else’s cat’s-paw.”

“I’m more afraid,” said Philippus gloomily, “that it’s Gaius Octavius will use others as his cat’s-paws.”

*To avoid confusion, it is not possible to start calling Gaius Octavius “Caesar” in narrative. By tradition he is known in these early years to history and historians as “Octavianus,” often rendered in English as “Octavian.” I shall use the simpler Octavian. The “ianus” suffix in Latin denotes that this name, put last, was the family to which the adopted man originally belonged. Thus, strictly speaking, Gaius Octavius became Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus. Octavian’s own habit in the early days of adding “Filius” to Caesar’s name simply indicates “son of.”