4

ORGANIZING OUR SOCIAL WORLD

How Humans Connect Now

On July 16, 2013, a mentally unstable New York woman abducted her seven-month-old son from a foster care agency in Manhattan. In such abduction cases, experience has shown that the chances of finding the child diminish drastically with each passing hour. Police feared for the infant boy’s safety, and with no leads, they turned to a vast social network created for national emergency alerts—they sent text messages to millions of cell phones throughout the city. Just before four A.M., countless New Yorkers were awakened by the text message:

The alert, which showed the license plate number of the car used to abduct the infant, resulted in someone spotting the car and calling the New York City Police Department, and the infant was safely recovered. The message broke through people’s attentional filter.

Three weeks later, the California Highway Patrol issued a regional, and later statewide, Amber Alert after two children were abducted near San Diego. The alert was texted to millions of cell phones in California, tweeted by the CHP, and repeated above California freeways on large displays normally used to announce traffic conditions. Again the victim was safely recovered.

It’s not just technology that has made this possible. We humans are hard-wired to protect our young, even the young of those not related to us. Whenever we read of terrorist attacks or war atrocities, the most wrenching and visceral reactions are to descriptions of children being harmed. This feeling appears to be culturally universal and innate.

The Amber Alert is an example of crowdsourcing—outsourcing to a crowd—the technique by which thousands or even millions of people help to solve problems that would be difficult or impossible to solve any other way. Crowdsourcing has been used for all kinds of things, including wildlife and bird counts, providing usage examples and quotes to the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary, and helping to decipher ambiguous text. The U.S. military and law enforcement have taken an interest in it because it potentially increases the amount of data they get by turning a large number of civilians into team members in information gathering. Crowdsourcing is just one example of organizing our social world—our social networks—to harness the energy, expertise, and physical presence of many individuals for the benefit of all. In a sense, it represents another form of externalizing the human brain, a way of linking the activities, perceptions, and cognitions of a large number of brains to a joint activity for the collective good.

In December 2009, DARPA offered $40,000 to anyone who could locate ten balloons that they had placed in plain sight around the continental United States. DARPA is the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, an organization under the U.S. Department of Defense. DARPA created the Internet (more precisely, they designed and built the first computer network, ARPANET, on which the current World Wide Web is modeled). At issue was how the United States might solve large-scale problems of national security and defense, and to test the country’s capacity for mobilization during times of urgent crisis. Replace “balloons” with “dirty bombs” or other explosives, and the relevance of the problem is clear.

On a predesignated day, DARPA hid ten large, red weather balloons, eight feet in diameter, in various places around the country. The $40,000 prize would be awarded to the first person or team anywhere in the world who could correctly identify the precise location of all ten balloons. When the contest was first announced, experts pointed out that the problem would be impossible to solve using traditional intelligence-gathering techniques.

There was great speculation in the scientific community about how the problem would be solved—for weeks, it filled up lunchroom chatter at universities and research labs around the world. Most assumed the winning team would use satellite imagery, but that’s where the problem gets tricky. How would they divide up the United States into surveillable sections with a high-enough resolution to spot the balloons, but still be able to navigate the enormous number of photographs quickly? Would the satellite images be analyzed by rooms full of humans, or would the winning team perfect a computer-vision algorithm for distinguishing the red balloons from other balloons and from other round, red objects that were not the target? (Effectively solving the Where’s Waldo? problem, something that computer programs couldn’t do until 2011.)

Further speculation revolved around the use of reconnaissance planes, telescopes, sonar, and radar. And what about spectrograms, chemical sensors, lasers? Tom Tombrello, physics professor at Caltech, favored a sneaky approach: “I would have figured out a way to get to the balloons before they were launched, and planted GPS tracking devices on them. Then finding them is trivial.”

The contest was entered by 53 teams totaling 4,300 volunteers. The winning team, a group of researchers from MIT, solved the problem in just under nine hours. How did they do it? Not via the kinds of high-tech satellite imaging or reconnaissance that many imagined, but—as you may have guessed—by constructing a massive, ad hoc social network of collaborators and spotters—in short, by crowdsourcing. The MIT team allocated $4,000 to finding each balloon. If you happened to spot the balloon in your neighborhood and provided them with the correct location, you’d get $2,000. If a friend of yours whom you recruited found it, your friend would get the $2,000 and you’d get $1,000 simply for encouraging your friend to join the effort. If a friend of your friend found the balloon, you’d get $500 for this third-level referral, and so on. The likelihood of any one person spotting a balloon is infinitesimally small. But if everyone you know recruits everyone they know, and each of them recruits everyone they know, you build a network of eyes on the ground that theoretically can cover the entire country. One of the interesting questions that social networking engineers and Department of Defense workers had wondered about is how many people it would take to cover the entire country in the event of a real national emergency, such as searching for an errant nuclear weapon. In the case of the DARPA balloons, it required only 4,665 people and fewer than nine hours.

A large number of people—the public—can often help to solve big problems outside of traditional institutions such as public agencies. Wikipedia is an example of crowdsourcing: Anyone with information is encouraged to contribute, and through this, it has become the largest reference work in the world. What Wikipedia did for encyclopedias, Kickstarter did for venture capital: More than 4.5 million people have contributed over $750 million to fund roughly 50,000 creative projects by filmmakers, musicians, painters, designers, and other artists. Kiva applied the concept to banking, using crowdsourcing to kick-start economic independence by sponsoring microloans that help start small businesses in developing countries. In its first nine years, Kiva has given out loans totaling $500 million to one million people in seventy different countries, with crowdsourced contributions from nearly one million lenders.

The people who make up the crowd in crowdsourcing are typically amateurs and enthusiastic hobbyists, although this doesn’t necessarily have to be the case. Crowdsourcing is perhaps most visible as a form of consumer ratings via Yelp, Zagat, and product ratings on sites such as Amazon.com. In the old, pre-Internet days, a class of workers existed who were expert reviewers and they would share their impressions of products and services in newspaper articles or magazines such as Consumer Reports. Now, with TripAdvisor, Yelp, Angie’s List, and others of their ilk, ordinary people are empowered to write reviews about their own experiences. This cuts both ways. In the best cases, we are able to learn from the experiences of hundreds of people about whether this motel is clean and quiet, or that restaurant is greasy and has small portions. On the other hand, there were advantages to the old system. The pre-Internet reviewers were professionals—they performed reviews for a living—and so they had a wealth of experience to draw on. If you were reading a restaurant review, you’d be reading it from someone who had eaten in a lot of restaurants, not someone who has little to compare it to. Reviewers of automobiles and hi-fi equipment had some expertise in the topic and could put a product through its paces, testing or paying attention to things that few of us would think of, yet might be important—such as the functioning of antilock brakes on wet pavement.

Crowdsourcing has been a democratizing force in reviewing, but it must be taken with a grain of salt. Can you trust the crowd? Yes and no. The kinds of things that everybody likes may not be the kinds of things you like. Think of a particular musical artist or book you loved but that wasn’t popular. Or a popular book or movie that, in your opinion, was awful. On the other hand, for quantitative judgments, crowds can come close. Take a large glass jar filled with many hundreds of jelly beans and ask people to guess how many are in it. While the majority of answers will probably be very wrong, the group average comes surprisingly close.

Amazon, Netflix, Pandora, and other content providers have used the wisdom of the crowd in a mathematical algorithm called collaborative filtering. This is a technique by which correlations or co-occurrences of behaviors are tracked and then used to make recommendations. If you’ve seen a little line of text on websites that says something like “customers who bought this also enjoyed that,” you’ve experienced collaborative filtering firsthand. The problem with these algorithms is that they don’t take into account a host of nuances and circumstances that might interfere with their accuracy. If you just bought a gardening book for Aunt Bertha, you may get a flurry of links to books about gardening—recommended just for you!—because the algorithm doesn’t know that you hate gardening and only bought the book as a gift. If you’ve ever downloaded movies for your children, only to find that the website’s movie recommendations to you became overwhelmed by G-rated fare when you’re looking for a good adult drama, you’ve seen the downside.

Navigation systems also use a form of crowdsourcing. When the Waze app on your smartphone, or Google Maps, is telling you the best route to the airport based on current traffic patterns, how do they know where the traffic is? They’re tracking your cell phone and the cell phones of thousands of other users of the applications to see how quickly those cell phones move through traffic. If you’re stuck in a traffic jam, your cell phone reports the same GPS coordinates for several minutes; if traffic is moving swiftly, your cell phone moves as quickly as your car and these apps can recommend routes based on that. As with all crowdsourcing, the quality of the overall system depends crucially on there being a large number of users. In this respect they’re similar to telephones, fax machines, and e-mail: If only one or two people have them, they are not much good—their utility increases with the number of users.

Artist and engineer Salvatore Iaconesi used crowdsourcing to understand treatment options for his brain cancer by placing all of his medical records online. He received over 500,000 responses. Teams formed, as physicians discussed medical options with one another. “The solutions came from all over the planet, spanning thousands of years of human history and traditions,” says Iaconesi. Wading through the advice, he chose conventional surgery in combination with some alternative therapies, and the cancer is now in remission.

One of the most common applications of crowdsourcing is hidden behind the scenes: reCAPTCHAs. These are the distorted words that are often displayed on websites. Their purpose is to prevent computers, or “bots,” from gaining access to secure websites, because such problems are difficult to solve for computers and usually not too difficult for humans. (CAPTCHA is an acronym for Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart. reCAPTCHAs are so-named for recycling—because they recycle human processing power.) reCAPTCHAs act as sentries against automated programs that attempt to infiltrate websites to steal e-mail addresses and passwords, or just to exploit weaknesses (for example, computer programs that might buy large numbers of concert tickets and then attempt to sell them at inflated prices). The source of these distorted words? In many cases they are pages from old books and manuscripts that Google is digitizing and that Google’s computers have had difficulty in deciphering. Individually, each reCAPTCHA takes only about ten seconds to solve, but with more than 200 million of them being solved every day, this amounts to over 500,000 hours of work being done in one day. Why not turn all this time into something productive?

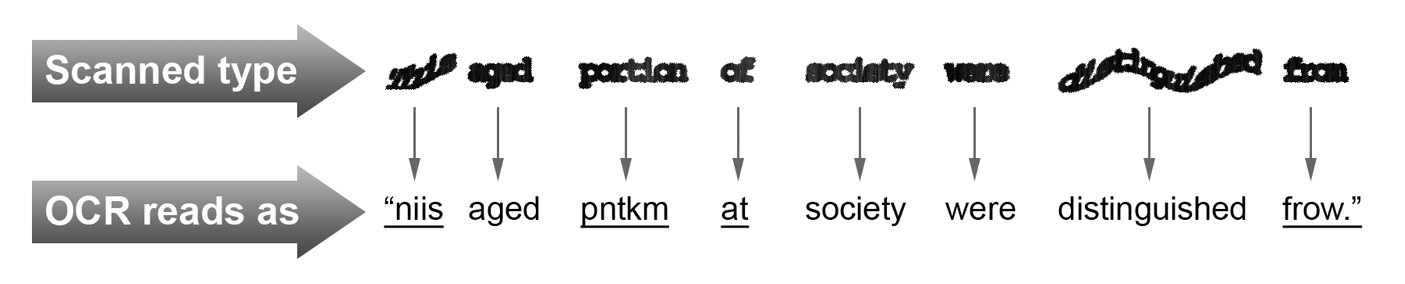

The technology for automatically scanning written materials and turning them into searchable text is not perfect. Many words that a human being can discern are misread by computers. Consider the following example from an actual book being scanned by Google:

After the text is scanned, two different OCR (for optical character recognition) programs attempt to map these blotches on the page to known words. If the programs disagree, the word is deemed unsolved, and then reCAPTCHA uses it as a challenge for users to solve. How does the system know if you guessed an unknown word correctly? It doesn’t! But reCAPTCHAs pair the unknown words with known words; they assume that if you solve the known word, you’re a human, and that your guess on the unknown word is reasonable. When several people agree on the unknown word, it’s considered solved and the information is incorporated into the scan.

Amazon’s Mechanical Turk is typically used for tasks that computers aren’t particularly good at but humans would find repetitively dull or boring. A recent cognitive psychology experiment published in Science used Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to find experimental participants. Volunteers (who were paid three dollars each) had to read a story and then take a test that measured their levels of empathy. Empathy requires the ability to switch between different perspectives on the same situation or interaction. This requires using the brain’s daydreaming mode (the task-negative network), and it involves the prefrontal cortex, cingulate, and their connections to the temporoparietal junction. Republicans and Democrats don’t use these empathy regions of their brains when thinking of one another. The research finding was that people who read literary fiction (as opposed to popular fiction or nonfiction) were better able to detect another person’s emotions, and the theory proposed was that literary fiction engages the reader in a process of decoding the characters’ thoughts and motives in a way that popular fiction and nonfiction, being less complex, do not. The experiment required hundreds of participants and would have taken a great deal more time to accomplish using physical participants in the laboratory.

Of course it is also a part of human nature to cheat, and anyone using crowdsourcing has to put into play checks and balances. When reading an online review of a restaurant, you can’t know that it was written by someone who actually dined there and not just the owner’s brother-in-law. For Wikipedia, those checks and balances are the sheer number of people who contribute to and review the articles. The underlying assumption is that cheaters, liars, and others with mild to extreme sociopathy are the minority in any given assemblage of people, and the white hats will triumph over the black hats. This is unfortunately not always true, but it appears to be true enough of the time for crowdsourcing to be useful and mostly trustworthy. It’s also, in many cases, a cost-saving alternative to a phalanx of paid experts.

Pundits have argued that “the crowd is always right,” but this is demonstrably not true. Some people in the crowd can be stubborn and dogmatic while simultaneously being misinformed, and having a panel of expert overseers can go a long way toward improving the accuracy and success of crowdsourced projects such as Wikipedia. As New Yorker essayist Adam Gopnik explains,

When there’s easy agreement, it’s fine, and when there’s widespread disagreement on values or facts, as with, say, the origins of capitalism, it’s fine too; you get both sides. The trouble comes when one side is right and the other side is wrong and doesn’t know it. The Shakespeare authorship [Wikipedia] page and the Shroud of Turin page are scenes of constant conflict and are packed with unreliable information. Creationists crowd cyberspace every bit as effectively as evolutionists, and extend their minds just as fully. Our trouble is not the overall absence of smartness but the intractable power of pure stupidity.

Modern social networks are fraught with dull old dysfunction and wonderfully new opportunities.

Aren’t Modern Social Relations Too Complex to Organize?

Some of the largest changes we are facing as a society are cultural, changes to our social world and the way we interact with one another. Imagine you are living in the year 1200. You probably have four or five siblings, and another four or five who died before their second birthday. You live in a one-room house with a dirt floor and a fire in the center for warmth. You share that house with your parents, children, and an extended family of aunts, uncles, nephews, and nieces all crowded in. Your daily routines are intimately connected to those of about twenty family members. You know a couple hundred people, and you’ve known most of them all your life. Strangers are regarded with suspicion because it is so very unusual to encounter them. The number of people you’d encounter in a lifetime was fewer than the number of people you’d walk past during rush hour in present-day Manhattan.

By 1850, the average family group in Europe had dropped from twenty people to ten living in close proximity, and by 1960 that number was just five. Today, 50% of Americans live alone. Fewer of us are having children, and those who do are having fewer children. For tens of thousands of years, human life revolved around the family. In most parts of the industrialized world, it no longer does. Instead, we create multiple overlapping social worlds—at work, though hobbies, in our neighborhoods. We become friends with the parents of our children’s friends, or with the owners of our dog’s friends. We build and maintain social networks with our friends from college or high school, but less and less with family. We meet more strangers, and we incorporate them into our lives in very new ways.

Notions of privacy that we take for granted today were very different just two hundred years ago. It was common practice to share rooms and even beds at roadside inns well into the nineteenth century. Diaries tell of guests complaining about late-arriving guests who climbed into bed with them in the middle of the night. As Bill Bryson notes in his intimately detailed book At Home, “It was entirely usual for a servant to sleep at the foot of his master’s bed, regardless of what his master might be doing within the bed.”

Human social relations are based on habits of reciprocity, altruism, commerce, physical attraction, and procreation. And we have learned much about these psychological realities from the behavior of our nearest biological relatives, the monkeys and great apes. There are unpleasant by-products of social closeness—rivalry, jealousy, suspicion, hurt feelings, competition for increased social standing. Apes and monkeys live in much smaller social worlds than we do nowadays, typically with fewer than fifty individuals living in a unit. More than fifty leads to rivalries tearing them apart. In contrast, humans have been living together in towns and cities with tens of thousands of people for several thousand years.

A rancher in Wyoming or a writer in rural Vermont might not encounter anyone for a week, while a greeter at Walmart might make eye contact with 1,700 people a day. The people we see constitute much of our social world, and we implicitly categorize them, divvying them up into an almost endless array of categories: family, friends, coworkers, service providers (bank teller, grocery store clerk, dry cleaner, auto mechanic, gardener), professional advisors (doctors, lawyers, accountants). These categories are further subdivided—your family includes your nuclear family, relatives you look forward to seeing, and relatives you don’t. There are coworkers with whom you might go out for a beer after work, and those you wouldn’t. And context counts: The people you enjoy socializing with at work are not necessarily people you want to bump into on a weekend at the beach.

Adding to the complexity of social relationships are contextual factors that have to do with your job, where you live, and your personality. A rancher in Wyoming may count in his social world a small number of people that is more or less constant; entertainers, Fortune 500 CEOs, and others in the public eye may encounter hundreds of new people each week, some of whom they will want to interact with again for various personal or professional reasons.

So how do you keep track of this horde of people you want to connect with? Celebrity attorney Robert Shapiro recommends this practical system. “When I meet someone new, I make notes—either on their business card or on a piece of paper—about where and how I met them, their area of expertise, and if we were introduced by someone, who made the introduction. This helps me to contextualize the link I have to them. If we had a meal together, I jot down who else was at the meal. I give this all to my secretary and she types it up, entering it into my contacts list.

“Of course the system gets more elaborate for people I interact with regularly. Eventually as I get to know them, I might add to the contacts list the name of their spouse, their children, their hobbies, things we did together with places and dates, maybe their birthday.”

David Gold, regional medical product specialist for Pfizer, uses a related technique. “Suppose I met Dr. Ware in 2008. I write down what we talked about in a note app on my phone and e-mail it to myself. Then if I see him again in 2013, I can say ‘Remember we were talking about naltrexone or such-and-such.’” This not only provides context to interactions, but continuity. It grounds and organizes the minds of both parties, and so, too, the interaction.

Craig Kallman is the chairman and CEO of Atlantic Records in New York—his career depends on being able to stay in touch with an enormous number of people: agents, managers, producers, employees, business colleagues, radio station managers, retailers, and of course the many musicians on his label, from Aretha Franklin to Flo Rida, from Led Zeppelin to Jason Mraz, Bruno Mars, and Missy Elliott. Kallman has an electronic contacts list of 14,000 people. Part of the file includes when they last spoke and how they are connected to other people in his database. The great advantage that the computer brings to a database of this size is that you can search along several different parameters. A year from now, Kallman might remember only one or two things about a person he just met, but he can search the contacts list and find the right entry. He might remember only that he had lunch with him in Santa Monica about a year ago, or that he met a person through Quincy Jones. He can sort by the last date of contact to see whom he hasn’t caught up with in a while.

As we saw in Chapter 2, categories are often most useful when they have flexible, fuzzy boundaries. And social categories benefit from this greatly. The concept of “friend” depends on how far you are from home, how busy your social life is, and a number of other circumstances. If you run into an old high school friend while touring Prague, you might enjoy having dinner with him. But back home, where you know lots of people with whom you prefer spending time, you might never get together with him.

We organize our friendships around a variety of motivations and needs. These can be for historical reasons (we stay in touch with old friends from school and we like the sense of continuity to earlier parts of our lives), mutual admiration, shared goals, physical attractiveness, complementary characteristics, social climbing. . . . Ideally, friends are people with whom we can be our true selves, with whom we can fearlessly let our guard down. (Arguably, a close friend is someone with whom we can allow ourselves to enter the daydreaming attentional mode, with whom we can switch in and out of different modes of attention without feeling awkward.)

Friendships obviously also revolve around shared likes and dislikes—it’s easier to be friends with people when you like doing the same things. But even this is relative. If you’re a quilting enthusiast and there’s only one other in town, the shared interest may bring you together. But at a quilting convention, you may discover someone whose precise taste in quilts matches yours more specifically, hence more common ground and a potentially tighter bond. This is why that friend from back home is a welcome companion in Prague. (Finally! Someone else who speaks English and can talk about the Superbowl!) It’s also why that same friend is less interesting when you get back home, where there are people whose interests are more aligned with yours.

Because our ancestors lived in social groups that changed slowly, because they encountered the same people throughout their lives, they could keep almost every social detail they needed to know in their heads. These days, many of us increasingly find that we can’t keep track of all the people we know and new people we meet. Cognitive neuroscience says we should externalize information in order to clear the mind. This is why Robert Shapiro and Craig Kallman keep contact files with contextual information such as where they met someone new, what they talked about, or who introduced them. In addition, little tags or notes in the file can help to organize entries—work friends, school friends, childhood friends, best friends, acquaintances, friends of friends—and there’s no reason you can’t put multiple tags in an entry. In an electronic database, you don’t need to sort the entries, you can simply search for any that contain the keyword you’re interested in.

I recognize that this can seem like a lot of busywork—you’re spending your time organizing data about your social world instead of actually spending time with people. Keeping track of birthdays or someone’s favorite wine isn’t mutually exclusive with a social life that enjoys spontaneity, and it doesn’t imply having to tightly schedule every encounter. It’s about organizing the information you have to allow those spontaneous interactions to be more emotionally meaningful.

You don’t have to have as many people in your contact list as the CEO of Atlantic Records does to feel the squeeze of job, family, and time pressures that prevent you from having the social life you want. Linda, the executive assistant introduced in the last chapter, suggests one practical solution for staying in touch with a vast array of friends and social contacts—use a tickler. A tickler is a reminder, something that tickles your memory. It works best as a note in your paper or electronic calendar. You set a frequency—say every two months—that you want to check in with friends. When the reminder goes off, if you haven’t been in touch with them since the last time, you send them a note, text, phone call, or Facebook post just to check in. After a few of these, you’ll find you settle into a rhythm and begin to look forward to staying in touch this way; they may even start to call you reciprocally.

Externalizing memory doesn’t have to be in physical artifacts like calendars, tickler files, cell phones, key hooks, and index cards—it can include other people. The professor is the prime example of someone who may act as a repository for arcane bits of information you hardly ever need. Or your spouse may remember the name of that restaurant you liked so much in Portland. The part of external memory that includes other people is technically known as transactive memory, and includes the knowledge of who in your social network possesses the knowledge you seek—knowing, for example, that if you lost Jeffrey’s cell phone number, you can get it from his wife, Pam, or children, Ryder and Aaron. Or that if you can’t remember when Canadian Thanksgiving will be this year (and you’re not near the Internet), you can ask your Canadian friend Lenny.

Couples in an intimate relationship have a way of sharing responsibility for things that need to be remembered, and this is mostly implicit, without their actually assigning the task to each other. For example, in most couples, each member of the couple has an area of expertise that the other lacks, and these areas are known to both partners. When a new piece of information comes in that concerns the couple, the person with expertise accepts responsibility for the information, and the other person lets the partner do so (relieving themselves of having to). When information comes in that is neither partner’s area of expertise, there is usually a brief negotiation about who will take it on. These transactive memory strategies combine to ensure that information the couple needs will always be captured by at least one of the partners. This is one of the reasons why, after a very long relationship, if one partner dies, the other partner can be left stuck not knowing how vast swaths of day-to-day life are navigated. It can be said that much of our data storage is within the small crowd of our personal relationships.

A large part of organizing our social world successfully, like anything else, is identifying what we want from it. Part of our primate heritage is that most of us want to feel that we fit in somewhere and are part of a group. Which group we’re part of may matter less to some of us than others, as long as we’re part of a group and not left entirely on our own. Although there are individual differences, being alone for too long causes neurochemical changes that can result in hallucinations, depression, suicidal thoughts, violent behaviors, and even psychosis. Social isolation is also a risk factor for cardiac arrest and death, even more so than smoking.

And although many of us think we prefer being alone, we don’t always know what we want. In one experiment, commuters were asked about their ideal commute: Would they prefer to talk to the person next to them or sit quietly by themselves? Overwhelmingly, people said they’d rather sit by themselves—the thought of having to make conversation with their seatmate was abhorrent (I admit I would have said the same thing). Commuters were then assigned either to sit alone and “enjoy their solitude” or to talk to the person sitting next to them. Those who talked to their seatmate reported having a significantly more pleasant commute. And the findings weren’t due to differences in personality—the results held up whether the individuals were outgoing or shy, open or reserved.

In the early days of our species, group membership was essential for protection from predators and enemy tribes, for the sharing of limited food resources, the raising of children, and care when injured. Having a social network fulfills a deep biological need and activates regions of the brain in the anterior prefrontal cortex that help us to position ourselves in relation to others, and to monitor our social standing. It also activates emotional centers in the brain’s limbic system, including the amygdala, and helps us to regulate emotions. There is comfort in belonging.

Enter social networking sites. From 2006 to 2008, MySpace was the most visited social networking site in the world, and was the most visited website of any kind in the United States, surpassing even Google. Today, it is the Internet equivalent of a ghost town with digital tumbleweeds blowing through its empty streets. Facebook rapidly grew to be the dominant social networking site and currently has more than 1.2 billion regular monthly users, more than one out of every seven people on the planet. How did it do this? It appealed to our sense of novelty, and our drive to connect to other people. It has allowed us to keep in touch with a large number of people with only a small investment of time. (And for those people who really just want to be left alone, it allows them to stay connected with others without having to actually see them in person!)

After a whole lifetime of trying to keep track of people, and little slips of paper with their phone numbers and addresses on them, now you can look people up by name and see what they’re doing, and let them know what you’re doing, without any trouble. Remember that, historically, we grew up in small communities and everyone we knew as children we knew the rest of our lives. Modern life doesn’t work this way. We have great mobility. We go off to college or to work. We move away when we start a family. Our brains carry around a vestigial primordial longing to know where all these people in our lives ended up, to reconnect, to get a sense of resolution. Social networking sites allow us to do all this without demanding too much time. On the other hand, as many have observed, we lost touch with these people for a reason! There was a natural culling; we didn’t keep up with people whom we didn’t like or whose relevance to our lives diminished over time. Now they can find us and have an expectation that we can be found. But for millions of people, the pluses outweigh the minuses. We get news feeds, the equivalent of the town crier or hair salon gossip, delivered to our tablets and phones in a continuous stream. We can tailor those streams to give us contact with what or whom we most care about, our own personal social ticker tape. It’s not a replacement for personal contact but a supplement, an easy way to stay connected to people who are far-flung and, well, just busy.

There is perhaps an illusion in all of this. Social networking provides breadth but rarely depth, and in-person contact is what we crave, even if online contact seems to take away some of that craving. In the end, the online interaction works best as a supplement, not a replacement for in-person contact. The cost of all of our electronic connectedness appears to be that it limits our biological capacity to connect with other people. Another see-saw in which one replaces the other in our attention.

Apart from the minimum drive to be part of a group or social network, many of us seek something more—having friends to do things with, to spend leisure or work time with; a circle of people who understand difficulties we may be encountering and offer assistance when needed; a relationship providing practical help, praise, encouragement, confidences, and loyalty.

Beyond companionship, couples seek intimacy, which can be defined as allowing another person to share and have access to our private behaviors, personal thoughts, joys, hurts, and fears of being hurt. Intimacy also includes creating shared meaning—those inside jokes, that sideways glance that only your sweetie understands—a kind of telepathy. It includes the freedom to be who we are in a relationship (without the need to project a false sense of ourselves) and to allow the other person to do the same. Intimacy allows us to talk openly about things that are important to us, and to take a clear stand on emotionally charged issues without fear of being ridiculed or rejected. All this describes a distinctly Western view—other cultures don’t view intimacy as a necessity or even define it in the same way.

Not surprisingly, men and women have different images of what intimacy entails: Women are more focused than men on commitment and continuity of communication, men on sexual and physical closeness. Intimacy, love, and passion don’t always go together of course—they belong to completely different, multidimensional constructs. We hope friendship and intimacy involve mutual trust, but they don’t always. Just like our chimpanzee cousins, we appear to have an innate tendency to deceive when it is in our own self-interest (the cause of untold amounts of frustration and heartache, not to mention sitcom plots).

Modern intimacy is much more varied, plural, and complex than it was for our ancestors. Throughout history and across cultures, intimacy was rarely regarded with the importance or emphasis we place on it now. For thousands of years—the first 99% of our history—we didn’t do much of anything except procreate and survive. Marriage and pair-bonding (the term that biologists use) was primarily sought for reproduction and for social alliances. Many marriages in historical times took place to create bonds between neighboring tribes as a way to defuse rivalries and tensions over limited resources.

A consequence of changing definitions of intimacy is that today, many of us ask more than ever of our romantic partners. We expect them to be there for emotional support, companionship, intimacy, and financial support, and we expect at various times they will function as confidante, nurse, sounding board, secretary, treasurer, parent, protector, guide, cheerleader, masseuse or masseur, and through it all we expect them to be consistently alluring, sexually appealing, and to stay in lockstep with our own sexual appetites and preferences. We expect our partners to help us achieve our full potential in life. And increasingly they do.

Our increased desire for our partners to do all these things is rooted in a biological need to connect deeply with at least one other person. When it is missing, making such a connection becomes a high priority. When that need is fulfilled by a satisfying intimate relationship, the benefits are both psychological and physiological. People in a relationship experience better health, recover from illnesses more quickly, and live longer. Indeed, the presence of a satisfying intimate relationship is one of the strongest predictors of happiness and emotional well-being that has ever been measured. How do we enter into and maintain intimate relationships? One important factor is the way that personality traits are organized.

Of the thousands of ways that human beings differ from one another, perhaps the most important trait for getting along with others is agreeableness. In the scientific literature, to be agreeable is to be cooperative, friendly, considerate, and helpful—attributes that are more or less stable across the lifetime, and show up early in childhood. Agreeable people are able to control undesirable emotions such as anger and frustration. This control happens in the frontal lobes, which govern impulse control and help us to regulate negative emotions, the same region that governs our executive attention mode. When the frontal lobes are damaged—from injury, stroke, Alzheimer’s, or a tumor, for example—agreeableness is often among the first things to go, along with impulse control and emotional stability. Some of this emotional regulation can be learned—children who receive positive reinforcement for impulse control and anger management become agreeable adults. As you might imagine, being an agreeable person is a tremendous advantage for maintaining positive social relationships.

During adolescence, when behavior is somewhat unpredictable and strongly influenced by interpersonal relations, we react and are guided by what our friends are doing to a much larger degree. Indeed, a sign of maturity is the ability to think independently and come to one’s own conclusions. It turns out that having a best friend during adolescence is an important part of becoming a well-adjusted adult. Those without one are more likely to be bullied and marginalized and to carry these experiences into becoming disagreeable adults. And although being agreeable is important for social outcomes later in life, just having a friend who is agreeable also protects against social problems later in life, even if you yourself are not. Both girls and boys benefit from having an agreeable friend, although girls benefit more than boys.

Intimate relationships, including marriage, are subject to what behavioral economists call strong sorting patterns along many different attributes. For example, on average, marriage partners tend to be similar in age, education level, and attractiveness. How do we find each other in an ocean of strangers?

Matchmaking or “romantic partner assistance” is not new. The Bible describes commercial matchmakers from over two thousand years ago, and the first publications to resemble modern newspapers in the early 1700s carried personal advertisements of people (mostly men) looking for a spouse. At various times in history, when people were cut off from potential partners—early settlers of the American West, Civil War soldiers, for example—they took to advertising for partners or responding to ads placed by potential partners, providing a list of attributes or qualities. As the Internet came of age in the 1990s, online dating was introduced as an alternative to personals ads and, in some cases, to matchmakers, via sites that advertised the use of scientific algorithms to increase compatibility scores.

The biggest change in dating between 2004 and 2014 was that one-third of all marriages in America began with online relationships, compared to a fraction of that in the decade before. Half of these marriages began on dating sites, the rest via social media, chat rooms, instant messages, and the like. In 1995, it was still so rare for a marriage to have begun online that newspapers would report it, breathlessly, as something weirdly futuristic and kind of freakish.

This behavioral change isn’t so much because the Internet itself or the dating options have changed; it’s because the population of Internet users has changed. Online dating used to be stigmatized as a creepier extension of the somewhat seedy world of 1960s and 1970s personal ads—the last resort for the desperate or undatable. The initial stigma associated with online dating became irrelevant as a new generation of users emerged for whom online contact was already well known, respectable, and established. And, like fax machines and e-mail, the system works only when a large number of people use it. This started to occur around 1999–2000. By 2014, twenty years after the introduction of online dating, younger users have a higher probability of embracing it because they have been active users of the Internet since they were little children, for education, shopping, entertainment, games, socializing, looking for a job, getting news and gossip, watching videos, and listening to music.

As already noted, the Internet has helped some of us to become more social and to establish and maintain a larger number of relationships. For others, particularly heavy Internet users who are introverted to begin with, the Internet has led them to become less socially involved, lonelier, and more likely to become depressed. Studies have shown a dramatic decline in empathy among college students, who apparently are far less likely to say that it is valuable to put oneself in the place of others or to try and understand their feelings. It is not just because they’re reading less literary fiction, it’s because they’re spending more time alone under the illusion that they’re being social.

Online dating is organized differently from conventional dating in four key ways—access, communication, matching, and asynchrony. Online dating gives us access to a much larger and broader set of potential mates than we would have encountered in our pre-Internet lives. The field of eligibles used to be limited to people we knew, worked with, worshipped with, went to school with, or lived near. Many dating sites boast millions of users, dramatically increasing the size of the pool. In fact, the roughly two billion people who are connected to the Internet are potentially accessible. Naturally, access to millions of profiles doesn’t necessarily mean access to electronic or face-to-face encounters; it simply allows users to see who else is available, even though the availables may not be reciprocally interested in you.

The communication medium of online dating allows us to get to know the person, review a broad range of facts, and exchange information before the stress of meeting face-to-face, and perhaps to avoid an awkward face-to-face meeting if things aren’t going well. Matching typically occurs via mathematical algorithms to help us select potential partners, screening out those who have undesirable traits or lack of shared interests.

Asynchrony allows both parties to gather their thoughts in their own time before responding, and thus to present their best selves without all of the pressure and anxiety that occurs in synchronous real-time interactions. Have you ever left a conversation only to realize hours later the thing you wish you had said? Online dating solves that.

Taken together, these four key features that distinguish Internet dating are not always desirable. For one thing, there is a disconnect between what people find attractive in a profile and what they find in meeting a person face-to-face. And, as Northwestern University psychologist Eli Finkel points out, this streamlined access to a pool of thousands of potential partners “can elicit an evaluative, assessment-oriented mind-set that leads online daters to objectify potential partners and might even undermine their willingness to commit to one of them.”

It can also cause people to make lazy, ill-advised decisions due to cognitive and decision overload. We know from behavioral economics—and decisions involving cars, appliances, houses, and yes, even potential mates—that consumers can’t keep track of more than two or three variables of interest when evaluating a large number of alternatives. This is directly related to the capacity limitations of working memory, discussed in Chapter 2. It’s also related to limitations of our attentional network. When considering dating alternatives, we necessarily need to get our minds to shuttle back and forth between the central executive mode—keeping track of all those little details—and the daydreaming mode, the mode in which we try to picture ourselves with each of the attractive alternatives: what our life would be like, how good they’ll feel on our arm, whether they’ll get along with our friends, and what our children will look like with his or her nose. As you now know, all that rapid switching between central executive calculating and dreamy mind-wandering depletes neural resources, leading us to make poor decisions. And when cognitive resources are low, we have difficulty focusing on relevant information and ignoring the irrelevant. Maybe online dating is a form of social organization that has gone off the rails, rendering decision-making more difficult rather than less.

Staying in any committed, monogamous relationship, whether it began online or off, requires fidelity, or “forgoing the forbidden fruit.” This is known to be a function of the availability of attractive alternatives. The twist with the advent of online dating, however, is that there can be many thousands of times more in the virtual world than in the off-line world, creating a situation where temptation can exceed willpower for both men and women. Stories of people (usually men) who “forgot” to take their dating profile down after meeting and beginning a serious relationship with someone are legion.

With one-third of people who get married meeting online, the science of online courtship has recently come into its own. Researchers have shown what we all suspected: Online daters engage in deception; 81% lie about their height, weight, or age. Men tend to lie about height, women about weight. Both lie about their age. In one study, age discrepancies of ten years were observed, weight was underreported by thirty-five pounds, and height was overreported by two inches. It’s not as though these things would be undiscovered upon meeting in person, which makes the misrepresentations more odd. And apparently, in the online world, political leaning is more sensitive and less likely to be disclosed than age, height, or weight. Online daters are significantly more likely to admit they’re fat than that they’re Republicans.

In the vast majority of these cases, the liars are aware of the lies they’re telling. What motivates them? Because of the large amount of choice that online daters have, the profile results from an underlying tension between wanting to be truthful and wanting to put one’s best face forward. Profiles often misrepresent the way you were sometime in the recent past (e.g., employed) or the way you’d like to be (e.g., ten pounds thinner and six years younger).

Social world organization gone awry or not, the current online dating world shows at least one somewhat promising trend: So far, there is a 22% lower risk of marriages that began online ending in divorce. But while that may sound impressive, the actual effect is tiny: Meeting online reduces the overall risk of divorce from 7.7% to 6%. If all the couples who met off-line met online instead, only 1 divorce for every 100 marriages would be prevented. Also, couples who met on the Web tend to be more educated and are more likely to be employed than couples who met in person, and educational attainment and employment tend to predict marital longevity. So the observed effect may not be due to Internet dating per se, but to the fact that Internet daters tend to be more educated and employed, as a group, than conventional daters.

As you might expect, couples who initially met via e-mail tend to be older than couples who met their spouse through social networks and virtual worlds. (Young people just don’t use e-mail very much anymore.) And like DARPA, Wikipedia, and Kickstarter, online dating sites that use crowdsourcing have cropped up. ChainDate, ReportYourEx, and the Lulu app are just three examples of a kind of Zagat-like rating system for dating partners.

Once we are in a relationship, romantic or platonic, how well do we know the people we care about, and how good are we at knowing their thoughts? Surprisingly bad. We are barely better than 50/50 in assessing how our friends and coworkers feel about us, or whether they even like us. Speed daters are lousy at assessing who wants to date them and who does not (so much for intuition). On the one hand, couples who thought they knew each other well correctly guessed their partner’s reactions four out of ten times—on the other hand, they thought they were getting eight out of ten correct. In another experiment, volunteers watched videos of people either lying or telling the truth about whether they were HIV positive. People believed that they were accurate in detecting liars 70% of the time, but in fact, they did no better than 50%. We are very bad at telling if someone is lying, even when our lives depend on it.

This has potentially grave consequences for foreign policy. The British believed Adolf Hitler’s assurance in 1938 that peace would be preserved if he was given the land just over the Czech border. Thus the British discouraged the Czechs from mobilizing their army. But Hitler was lying, having already prepared his army to invade. The opposite misreading of intentions occurred when the United States believed Saddam Hussein was lying about not having any weapons of mass destruction—in fact, he was telling the truth.

Outside of military or strategic contexts, where lying is used as a tactic, why do people lie in everyday interactions? One reason is fear of reprisal when we’ve done something we shouldn’t. It is not the better part of human nature, but it is human nature to lie to avoid punishment. And it starts early—six-year-olds will say, “I didn’t do it,” while they’re in the middle of doing it! Workers on the Deepwater Horizon oil rig in the gulf waters off of Louisiana knew of safety problems but were afraid to report them for fear of being fired.

But it is also human nature to forgive, especially when we’re given an explanation. In one study, people who tried to cut in line were forgiven by others even if their explanation was ridiculous. In a line for a copy machine, “I’m sorry, may I cut in? I need to make copies” was every bit as effective as “I’m sorry, may I cut in? I’m on deadline.”

When doctors at the University of Michigan hospitals started disclosing their mistakes to patients openly, malpractice lawsuits were cut in half. The biggest impediment to resolution had been requiring patients to imagine what their doctors were thinking, and having to sue to find out, rather than just allowing doctors to explain how a mistake happened. When we’re confronted with the human element, the doctor’s constraints and what she is struggling with, we’re more likely to understand and forgive. Nicholas Epley, a professor at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business (and author of Mindwise), writes, “If being transparent strengthens the social ties that make life worth living, and enables others to forgive our shortcomings, why not do it more often?”

People lie for other reasons of course, not just fear of reprisals. Some of these include avoiding hurting other people’s feelings, and sometimes little white lies become the social glue that prevents tempers from flaring and minimizes antagonism. In this context, we are surprisingly good at telling when people are lying, and we go along with it, cooperatively, every day. It has to do with the gentle way we ask for things when we want to avoid confrontations with people—indirect speech acts.

Why People Are Indirect with Us

A large part of human social interaction requires that we subdue our innate primate hostilities in order to get along. Although primates in general are among the most social species, there are few examples of primate living groups that support more than eighteen males within the group—the interpersonal tensions and dominance hierarchies just become too much for them and they split apart. And yet humans have been living in cities containing tens of thousands of males for several millennia. How do we do it? One way of helping to keep large numbers of humans living in close proximity is through the use of nonconfrontational speech, or indirect speech acts. Indirect speech acts don’t say what we actually want, but they imply it. The philosopher Paul Grice called these implicatures.

Suppose John and Marsha are both sitting in an office, and Marsha’s next to the window. John feels hot. He could say, “Open the window,” which is direct and may make Marsha feel a little weird. If they’re workplace equals, who is John to tell Marsha what to do or to boss her around, she might think. If instead John says, “Gosh, it’s getting warm in here,” he is inviting her into a cooperative venture, a simple but not trivial unwrapping of what he said. He is implying his desire in a nondirective and nonconfrontational manner. Normally, Marsha plays along by inferring that he’d like her to open the window, and that he’s not simply making a meteorological observation. At this point, Marsha has several response choices:

a. She smiles back at John and opens the window, signaling that she’s playing this little social game and that she’s cooperating with the charade’s intent.

b. She says, “Oh really? I’m actually kind of chilly.” This signals that she is still playing the game but that they have a difference of opinion about the basic facts. Marsha’s being cooperative, though expressing a different viewpoint. Cooperative behavior on John’s part at this point requires him to either drop the subject or to up the ante, which risks raising levels of confrontation and aggression.

c. Marsha can say, “Oh yes—it is.” Depending on how she says it, John might take her response as flirtatious and playful, or sarcastic and rude. In the former case, she’s inviting John to be more explicit, effectively signaling that they can drop this subterfuge; their relationship is solid enough that she is giving John permission to be direct. In the latter case, if Marsha uses a sarcastic tone of voice, she’s indicating that she agrees with the premise—it’s hot in there—but she doesn’t want to open the window herself.

d. Marsha can say, “Why don’t you take off your sweater.” This is noncooperative and a bit confrontational—Marsha is opting out of the game.

e. Marsha can say, “I was hot, too, until I took off my sweater. I guess the heating system finally kicked in.” This is less confrontational. Marsha is agreeing with the premise but not the implication of what should be done about it. It is partly cooperative in that she is helping John to solve the problem, though not in the way he intended.

f. Marsha can say, “Screw you.” This signals that she doesn’t want to play the implicature game, and moreover, she is conveying aggression. John’s options are limited at this point—either he can ignore her (effectively backing down) or he can up the ante by getting up, stomping past her desk, and forcefully opening the damn window. (Now it’s war.)

The simplest cases of speech acts are those in which the speaker utters a sentence and means exactly and literally what he says. Yet indirect speech acts are a powerful social glue that enables us to get along. In them, the speaker means exactly what she says but also something more. The something more is supposed to be apparent to the hearer, and yet it remains unspoken. Hence, the act of uttering an indirect speech act can be seen as inherently an act of play, an invitation to cooperate in a game of verbal hide-and-seek of “Do you understand what I’m saying?” The philosopher John Searle says the mechanism by which indirect speech acts work is that they invoke in both the speaker and the hearer a shared representation of the world; they rely on shared background information that is both linguistic and social. By appealing to their shared knowledge, the speaker and listener are creating a pact and affirming their shared worldview.

Searle asks us to consider another type of case with two speakers, A and B.

A: Let’s go to the movies tonight.

B: I have to study for an exam tonight.

Speaker A is not making an implicature—it can be taken at face value as a direct request, as marked by the use of let’s. But Speaker B’s reply is clearly indirect. It is meant to communicate both a literal message (“I’m studying for an exam tonight”) and an unspoken implicature (“Therefore I can’t go to the movies”). Most people agree that B is employing a gentler way of resolving a potential conflict between the two people by avoiding confrontation. If instead, B said

B1: No.

speaker A feels rejected, and without any cause or explanation. Our fear of rejection is understandably very strong; in fact, social rejection causes activation in the same part of the brain as physical pain does, and—perhaps surprisingly and accordingly—Tylenol can reduce people’s experience of social pain.

Speaker B makes the point in a cooperative framework, and by providing an explanation, she implies that she really would like to go, but simply cannot. This is equivalent to the person cutting in line to make copies and providing a meaningless explanation that is better received than no explanation at all. But not all implicatures are created equal. If instead, B had said

B2: I have to wash my hair tonight.

or

B3: I’m in the middle of a game of solitaire that I really must finish.

then B is expecting that A will understand these as rejections, and offers no explanatory niceties—a kind of conversational slap in the face, albeit one that extends the implicature game. B2 and B3 constitute slightly gentler ways of refusing than B1 because they do not involve blatant and outright contradiction.

Searle extends the analysis of indirect speech acts to include utterances whose meaning may be thoroughly indecipherable but whose intent, if we’re lucky, is one hundred percent clear. He asks us to consider the following. Suppose you are an American soldier captured by the Italians during World War II while out of uniform. Now, in order to get them to release you, you devise a plan to convince them that you are a German officer. You could say to them in Italian, “I am a German officer,” but they might not believe it. Suppose further that you don’t speak enough Italian in the first place to say that.

The ideal utterance in this case would be for you to say, in perfect German, “I am a German officer. Release me, and be quick about it.” Suppose, though, that you don’t know enough German to say that, and all you know is one line that you learned from a German poem in high school: “Kennst du das Land, wo die Zitronen blühen?” which means “Knowest thou the land where the lemon trees bloom?” If your Italian captors don’t speak any German, your saying “Kennst du das Land, wo die Zitronen blühen?” has the effect of communicating that you are German. In other words, the literal meaning of your speech act becomes irrelevant, and only the implied meaning is at work. The Italians hear what they recognize only as German, and you hope they will make the logical leap that you must indeed be German and therefore worthy of release.

Another aspect of communication is that information can become updated through social contracts. You might mention to your friend Bert that Ernie said such-and-such, but Bert adds the new information that we now know Ernie’s a liar and can’t be trusted. We learned that Pluto is no longer a planet when a duly authorized panel, empowered by society to make such decisions and judgments, said so. Certain utterances have, by social contract, the authority to change the state of the world. A doctor who pronounces you dead changes your legal status instantly, which has the effect of utterly changing your life, whether you’re in fact dead or not. A judge can pronounce you innocent or guilty and, again, the truth doesn’t matter as much as the force of the pronouncement, in terms of what your future looks like. The set of utterances that can so change the state of the world is limited, but they are powerful. We empower these legal or quasi-legal authorities in order to facilitate our understanding of the social world.

Except for these formal and legalistic pronouncements, Grice and Searle take as a premise that virtually all conversations are a cooperative undertaking and that they require both literal and implied meanings to be processed. Grice systematized and categorized the various rules by which ordinary, cooperative speech is conducted, helping to illuminate the mechanisms by which indirect speech acts work. The four Gricean maxims are:

- Quantity. Make your contribution to the conversation as informative as required. Do not make your contribution more informative than is required.

- Quality. Do not say what you believe to be false. Do not say that for which you lack adequate evidence.

- Manner. Avoid obscurity of expression (don’t use words that your intended hearer doesn’t know). Avoid ambiguity. Be brief (avoid unnecessary prolixity). Be orderly.

- Relation. Make your contribution relevant.

The following three examples demonstrate violations of maxim 1, quantity, where the second speaker is not making a contribution that is informative enough:

A: Where are you going this afternoon?

B: Out.

A: How was your day?

A: What did you learn in school today?

B: Nothing.

Even if we don’t know about Gricean maxims, we intuitively recognize these replies as being noncooperative. The first speaker in each case is implying that he would like a certain level of detail in response to his query, and the second speaker is opting out of any cooperative agreement of the sort.

As another example, suppose Professor Kaplan is writing a recommendation for a pupil who is applying to graduate school.

“Dear Sir, Mr. X’s command of English is fine and his attendance in my class has been regular. Very truly yours, Professor Kaplan.”

By violating the maxim of quantity—not providing enough information—Professor Kaplan is implying that Mr. X is not a very good student, without actually saying it.

Here’s an example of the other extreme, in which the second speaker provides too much information:

A: Dad, where’s the hammer?

B: On the floor, two inches from the garage door, lying in a puddle of water where you left it three hours ago after I told you to put it back in the toolbox.

The second speaker in this case, by providing too much information, is implying more than the facts of the utterance, and is signaling annoyance.

A is standing by an obviously immobilized car when B walks by.

A: I’m out of gas.

B: There’s a garage just about a quarter mile down the street.

B is violating the maxim of quality if, in fact, there is no garage down the street, or if the speaker knows that the garage is open but has no gasoline. Suppose B wants to steal the tires from A’s car. A assumes that B is being truthful, and so walks off, giving B enough time to jack up the car and unmount a tire or two.

A: Where’s Bill?

B: There’s a yellow VW outside Sue’s house. . . .

B flouts the maxim of relevance, suggesting that A is to make an inference. A now has two choices:

- Accept B’s statement as flouting the maxim of relevance, and as an invitation to cooperate. A says (to himself): Bill drives a yellow VW. Bill knows Sue. Bill must be at Sue’s house (and B doesn’t want to come right out and say so for some reason; perhaps this is a delicate matter or B promised not to tell).

- Withdraw from B’s proposed dialogue and repeat the original question, “Yes, but where’s Bill?”

Of course B has other possible responses to the question “Where’s Bill?”:

B1: At Sue’s house. (no implicature)

B2: Well, I saw a VW parked at Sue’s house, and Bill drives a VW. (a mild implicature, filling in most of the blanks for A)

B3: What an impertinent question! (direct, somewhat confrontational)

B4: I’m not supposed to tell you. (less direct, still somewhat confrontational)

B5: I have no idea. (violating quality)

B6: [Turns away] (opting out of conversation)

Indirect speech acts such as these reflect the way we actually use language in everyday speech. There is nothing unfamiliar about these exchanges. The great contribution of Grice and Searle was that they organized the exchanges, putting them into a system whereby we can analyze and understand how they function. This all occurs at a subconscious level for most of us. Individuals with autism spectrum disorders often have difficulty with indirect speech acts because of biological differences in their brains that make it difficult for them to understand irony, pretense, sarcasm, or any nonliteral speech. Are there neurochemical correlates to getting along and keeping social bonds intact?

There’s a hormone in the brain released by the back half of the pituitary gland, oxytocin, that has been called by the popular press the love hormone, because it used to be thought that oxytocin is what causes people to fall in love with each other. When a person has an orgasm, oxytocin is released, and one of the effects of oxytocin is to make us feel bonded to others. Evolutionary psychologists have speculated that this was nature’s way of causing couples to want to stay together after sex to raise any children that might result from that sex. In other words, it is clearly an evolutionary advantage for a child to have two caring, nurturing parents. If the parents feel bonded to each other through oxytocin release, they are more likely to share in the raising of their children, thus propagating their tribe.

In addition to difficulty understanding any speech that isn’t literal, individuals with autism spectrum disorders don’t feel attachment to people the way others do, and they have difficulty empathizing with others. Oxytocin in individuals with autism shows up at lower than normal levels, and the administration of oxytocin causes them to become more social, and improves emotion recognition. (It also reduces their repetitive behaviors.)

Oxytocin has additionally been implicated in feelings of trust. In a typical experiment, people watch politicians making speeches. The observers are under the influence of oxytocin for half the speeches they watch, and a placebo for the other half (of course they don’t know which is which). When asked to rate whom they trust the most, or whom they would be most likely to vote for, people select the candidates they viewed while oxytocin was in their system.

There’s a well-established finding that people who receive social support during illness (simple caring and nurturing) recover more fully and more quickly. This simple social contact when we’re sick also releases oxytocin, in turn helping to improve health outcomes by reducing stress levels and the hormone cortisol, which can cripple the immune system.

Paradoxically, levels of oxytocin also increase during gaps in social support or poor social functioning (thus absence does make the heart grow fonder—or at least more attached). Oxytocin may therefore act as a distress signal prompting the individual to seek out social contact. To reconcile this paradox—is oxytocin the love drug or the without-love drug?—a more recent theory gaining traction is that oxytocin regulates the salience of social information and is capable of eliciting positive and negative social emotions, depending on the situation and individual. Its real role is to organize social behavior. Promising preliminary evidence suggests that oxytocin pharmacotherapy can help to promote trust and reduce social anxiety, including in people with social phobia and borderline personality disorder. Nondrug therapies, such as music, may exert similar therapeutic effects via oxytocinergic regulation; music has been shown to increase oxytocin levels, especially when people listen to or play music together.

A related chemical in the brain, a protein called arginine vasopressin, has also been found to regulate affiliation, sociability, and courtship. If you think your social behaviors are largely under your conscious control, you’re underestimating the role of neurochemicals in shaping your thoughts, feelings, and actions. To wit: There are two species of prairie voles; one is monogamous, the other is not. Inject vasopressin in the philandering voles and they become monogamous; block vasopressin in the monogamous ones and they become as randy as Gene Simmons in a John Holmes movie.

Injecting vasopressin also causes innate, aggressive behaviors to become more selective, protecting the mate from emotional (and physical) outbursts.

Recreational drugs such as cannabis and LSD have been found to promote feelings of connection between people who take those drugs and others, and in many cases, a feeling of being more connected to the world-as-a-whole. The active ingredient in marijuana activates specialized neural receptors called cannabinoid receptors, and it has been shown experimentally in rats that they increase social activity (when the rats could get up off the couch). LSD’s action in the brain includes stimulating dopamine and certain serotonin receptors while attenuating sensory input from the visual cortex (which may be partly responsible for visual hallucinations). Yet the reason LSD causes feelings of social connection is not yet known.

In order to feel socially connected to others, we like to think we know them, and that to some extent we can predict their behavior. Take a moment to think about someone you know well—a close friend, family member, spouse, and so on, and rate that person according to the three options below.

The person I am thinking of tends to be:

|

a. |

subjective |

analytic |

depends on the situation |

|

b. |

energetic |

relaxed |

depends on the situation |

|

c. |

dignified |

casual |

depends on the situation |

|

d. |

quiet |

talkative |

depends on the situation |

|

e. |

cautious |

bold |

depends on the situation |

|

f. |

lenient |

firm |

depends on the situation |

|

g. |

intense |

calm |

depends on the situation |

|

h. |

realistic |

idealistic |

depends on the situation |

Now go back and rate yourself on the same items.

Most people rate their friend in terms of traits (the first two columns)but rate themselves in terms of situations (the third column). Why? Because by definition, we see only the public actions of others. For our own behaviors, we have access not just to the public actions but to our private actions, private feelings, and private thoughts as well. Our own lives seem to us to be more filled with rich diversity of thoughts and behaviors because we are experiencing a wider range of behaviors in ourselves while effectively having only one-sided evidence about others. Harvard psychologist Daniel Gilbert calls this the “invisibility” problem—the inner thoughts of others are invisible to us.

In Chapter 1, cognitive illusions were compared to visual illusions. They are a window into the inner workings of the mind and brain, and reveal to us some of the substructure that supports cognition and perception. Like visual illusions, cognitive illusions are automatic—that is, even when we know they exist, it is difficult or impossible to turn off the mental machinery that gives rise to them. Cognitive illusions lead us to misperceive reality and to make poor decisions about choices we are presented with, medical options, and interpreting the behaviors of other people, particularly those who comprise our social world. Misinterpreting the motivations of others leads to misunderstandings, suspicion, and interpersonal conflict and, in the worst cases, war. Fortunately, many cognitive illusions can be overcome with training.

One of the most well established findings in social psychology concerns how we interpret the actions of others, and it’s related to the demonstration above. There are two broad classes of explanation for why people do what they do—dispositional or situational. Dispositional explanations embrace the idea that all of us have certain traits (dispositions) that are more or less stable across our lifetimes. As you just saw, we have a tendency to describe the people we know in trait terms: They’re extroverts or introverts, agreeable or disagreeable, the life of the party or a stick-in-the-mud.

Situational explanations, on the other hand, acknowledge that momentary circumstances sometimes contribute to our responses and can override any innate predispositions. These oppositional approaches are sometimes characterized as “the person versus the situation.” Dispositional explanations say, “I was born (or made) that way.” Situational ones (to quote comedian Flip Wilson) say, “The devil made me do it.”

In one famous study, students at the Princeton Theological Seminary were asked to come into an office to provide their opinions on “religious education and vocations.” After they had filled out a series of questionnaires, the experimenter explained that questionnaires tend to be oversimplified, and so for the final part of the study, the students would be asked to record a three- to five-minute talk based on a short piece of text. The students were then given one of two things to read, either a paragraph exploring whether “ministering” can be effective within the professional clergy these days, or the parable of the Good Samaritan from the New Testament (who stopped to help an injured man after a priest and a Levite had passed him by on the road).

Now, in social psychology experiments, things are not usually as they seem—the experimenters go to great lengths to hide what they’re really up to, in order to reduce the possibility that participants will be able to tailor their behavior to the experiment. In this case, the experimenter told the participants that space was tight in the building they were in, and consequently he had made arrangements for the talk to be recorded in an office building next door (this was part of the deception). The experimenter then drew a map for the participants, showing them how to get there.

Thirteen participants in each reading group were told that they should hurry because an assistant in the adjacent building had expected them a few minutes earlier. Thirteen others were told, “It’ll be a few minutes before they’re ready for you, but you might as well head on over.” This constitutes a situational factor—some students are in a hurry, some are not. Some people are more helpful than others, a dispositional trait that we assume is more or less stable across a person’s lifetime. But this particular group—seminary students—are no doubt more helpful than the average person because they are studying to become members of the clergy, a helping profession. We assume that differences in the traits of helpfulness and compassion are minimized in this particular population, and moreover, any remaining individual differences would be evenly distributed across the two conditions of the study because the experimenters randomly assigned students to one condition or the other. The design of the experiment cleverly pits dispositional against situational factors.

Between the two Princeton campus buildings, the experimenters had placed a confederate—a research assistant—who sat slumped in a doorway and who appeared to be in need of medical attention. When each theological student passed by, the confederate coughed and groaned.

If you believe that a person’s traits are the best predictor of behavior, you would predict that all or most of the seminary students would stop and help this injured person. And, as an added, elegant twist to the experiment, half have just read the story of the Good Samaritan who stopped to help someone in a situation very much like this.

What did the experimenters find? The students who were in a hurry were six times more likely to keep on walking and pass by the visibly injured person without helping than the students who had plenty of time. The amount of time the students had was the situational factor that predicted how they would behave, and the paragraph they read had no significant effect.