7

ORGANIZING THE BUSINESS WORLD

How We Create Value

At midday on September 30, 2006, the de la Concorde overpass at Laval outside of Montreal collapsed onto Quebec Autoroute 19, a major north-south artery. Five people were killed and six others were seriously injured when their cars were thrown over the edge. During the bridge’s construction, the contractors had installed the steel reinforcing bars in the concrete incorrectly and, to save money, unilaterally decided to use a lower-quality concrete, which didn’t meet design specifications. The ensuing government inquiry determined that this caused the bridge to collapse. Several other cases of low-quality concrete used in bridges, overpasses, and highways were identified in Quebec during a government inquiry into corruption in the construction industry. The history of shoddy construction practices is long—the wooden amphitheater in Fidenae near ancient Rome was built on a poor foundation, in addition to being improperly constructed, causing its collapse in 27 CE with 20,000 casualties. Similar disasters have occurred around the world, including the Teton Dam in Idaho in 1976, the collapse of Sichuan schools in the Chinese earthquake of 2008, and the failure of the Myllysilta Bridge in Turku, Finland, in 2010.

When they work properly, large civic projects like these involve many specialists and levels of checks and balances. The design, decision-making, and implementation are structured throughout an organization in a way that increases the chances for success and value. Ideally, what everyone is working for is a state in which both human and material resources are allocated to achieve maximum value. (When all the components of a complex system achieve maximum value, and when it is impossible to make any one component of the system better without making at least one other component worse, the system can be said to have reached the Pareto optimum.) The asphalt worker paving a city street shouldn’t normally make the decision about what quality of paving materials to use or how thick the layer should be—these decisions are made by higher-ups who must optimize, taking into account budgets, traffic flow, weather conditions, projected years of use, standard customs and practices, and potential lawsuits if potholes develop. These different aspects of information gathering and decision-making are typically distributed throughout an organization and may be assigned to different managers who then report to their higher-ups, who in turn balance the various factors to achieve the city’s long-term goals, to satisfice this particular decision. As Adam Smith wrote in The Wealth of Nations in 1776, one of the greatest advances in work productivity was the division of labor. Dividing up tasks in any large human enterprise has proved extremely influential and useful.

Up until the mid 1800s, businesses were primarily small and family-run, serving only a local market. The spread of telegraph and railroads beginning in the mid 1800s made it possible for more companies to reach national and international markets, building on progress in maritime trade that had been developing for centuries. The need for documentation and functional specialization or cross-training grew dramatically along with this burgeoning long-distance commerce. The aggregate of letters, contracts, accounting, inventory, and status reports presented a new organizational challenge: How do you find that piece of information you need this afternoon inside this new mountain of paper? The Industrial Revolution ushered in the Age of Paperwork.

A series of railroad collisions in the early 1840s provided an urgent push toward improved documentation and functional specialization. Investigators concluded that the accidents resulted from communications among engineers and operators of various lines being handled too loosely. No one was certain who had authority over operations, and acknowledging receipt of important messages was not common practice. The railroad company investigators recommended standardizing and documenting operating procedures and rules. The aim was to transcend dependence upon the skills, memory, or capacity of any single individual. This involved writing a precise definition of duties and responsibilities for each job, coupled with standardized ways of performing these duties.

Functional specialization within the workforce became increasingly profitable and necessary so that things wouldn’t grind to a halt if that lone worker who knew how to do this one particular thing was out sick. This led to functionally compartmentalized companies, and an even greater need for paperwork so workers could communicate with their bosses (who might be a continent away), and so that one division of a company could communicate with other divisions. The methods of record keeping and the management style that worked for a small family-owned company simply didn’t scale to these new, larger firms.

Because of these developments, managers suddenly had greater control over the workers, specifically, over who was doing the work. Processes and procedures that had been kept in workers’ heads were now recorded in handbooks and shared within the company, giving each worker an opportunity to learn from prior workers and to add improvements. Such a move follows the fundamental principle of the organized mind: externalizing memory. This involves taking the knowledge from the heads of a few individuals and putting it (such as in the form of written job descriptions) out-there-in-the-world where others can see and use it.

Once management obtained detailed task and job descriptions, it was possible to fire a lazy or careless employee and replace him or her with someone else without a great loss of productivity—management simply communicated the details of the job and where things had been left off. This was essential in building and repairing the railroads, where great distances existed between the company headquarters and the workers in the field. Yet soon the drive to systematize jobs extended to managers, so managers became as replaceable as workers, a development promoted by the English efficiency engineer Alexander Hamilton Church.

The trend toward systematizing jobs and increasing organization efficiency led the Scottish engineer Daniel McCallum to create the first organizational charts in 1854 as a way to easily visualize reporting relationships among employees. A typical org chart shows who reports to whom; the downward arrows indicate a supervisor-to-supervisee relationship.

Org charts represent reporting hierarchies very well, but they don’t show how coworkers interact with one another; and although they show business relationships, they do not show personal relationships. Network diagrams were first introduced by the Romanian sociologist Jacob Moreno in the 1930s. They are more useful in understanding which employees work with and know one another, and they’re often used by management consultants to diagnose problems in structural organization, productivity, or efficiency.

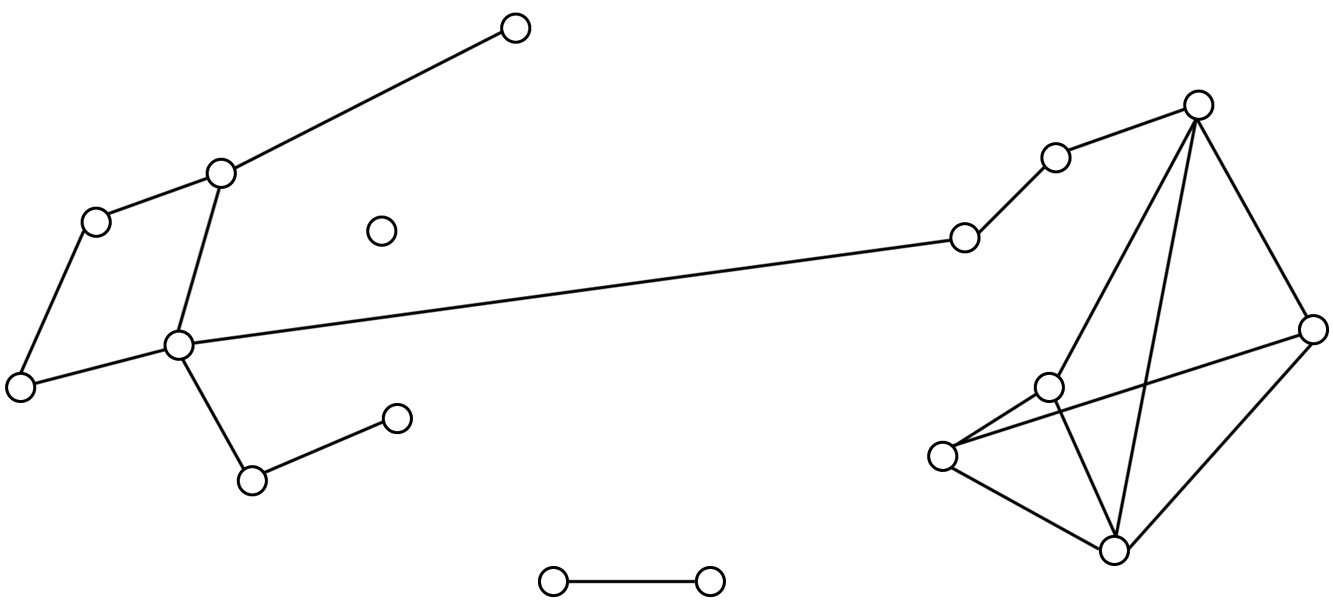

Below is the network diagram from a one-month survey of an Internet start-up company (the company was eventually sold to Sony). The diagram shows who interacted with whom during the month surveyed; the interactions shown are dichotomous, without attention to the number or quality of interactions. The diagram reveals that the founder (the node at the top) interacted with only one other person, his COO; the founder was on a fund-raising trip this particular month. The COO interacted with three people. One of them was in charge of product development, and he interacted with an employee who oversaw a network of seven consultants. The consultants interacted with one another a great deal.

Creating a network map allowed management to see that there was one person whom nobody ever talked to, and two people who interacted extensively with each other but no one else. Various forms of network diagrams are possible, including using “heat maps” in which colors indicate the degree of interaction (hotter colors mean more interaction along a node, colder colors mean less). Network maps can be used in conjunction with hierarchical organization charts to identify which members of an organization already know one another, which in turn can facilitate creating project teams or reorganizing certain functions and reporting structures. Standard organizational behavior practice is to split up teams that aren’t functioning efficiently and to try to replicate teams that are. But because team efficiency isn’t simply a matter of who has what skills, and is more a matter of interpersonal familiarity and who works well together, the network diagram is especially useful; it can track not just which team members work together but which, if any, socialize together outside of work (and this could be represented differentially with color or dotted lines, or any number of standard graphing techniques).

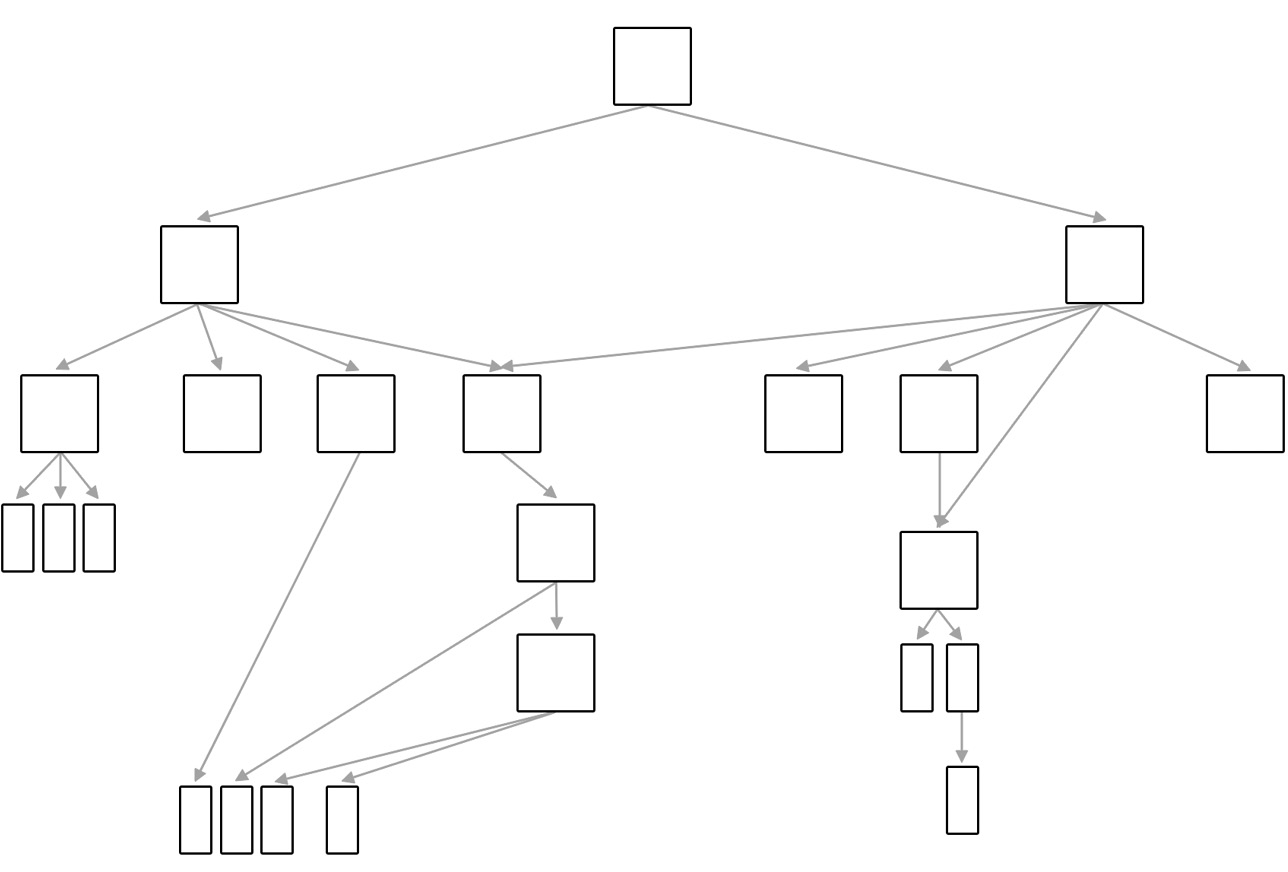

Organizations can have either flat (horizontal) or deep (vertical) hierarchies, which can have a great impact on employee and manager efficiency and effectiveness. Compare these two different org charts, for a flat company (left) with only three levels and a vertical company (right) with five levels:

The command structure in corporate and military organizations can take either form, and each system has advantages and disadvantages (conventional military structure is vertical, but terrorist and other cell-based groups typically use flat structure with decentralized control and communications).

A flat structure encourages people to work together and allows for overlap in effort, often empowering employees to do what needs to be done and apply their talents outside of formal command or task structure. A drawback of flat structure is that there may be only one person who has effective decision-making authority, and that person will have too many decisions to make. Due to the lack of a hierarchy, extra effort is needed to establish who has responsibility for which tasks. Indeed, some form of vertical structure is essential to achieve coordination among the employees and their projects, to avoid duplication of effort, and to ensure coherence across different components of a project. The additional advantage of vertical structure is that employees can more easily be held accountable for their decisions and their work product.

Tall vertical systems usually encourage specialization and the efficiencies that come from it. But tall structures can also result in employees being isolated from one another and working in silos, unaware of what others are doing that might be closely related to their own work. When a vertical system becomes too tall (too many levels), it can take too much time for instructions to filter down to the ground from higher up, or vice versa. Railroad companies led the way to more complex organization in the business world, and in the last fifty years the level of complexity has grown so that in many cases it is impossible to keep track of what everyone is doing. Fifty companies in the world have more than a quarter million employees, and seven companies in the world have more than one million.

Companies can be thought of as transactive memory systems. Part of the art of fitting into a company as a new employee, indeed part of becoming an effective employee (especially in upper management), is learning who holds what knowledge. If you want the 2014 sales figures for the southeastern region, you call Rachel, but she has the figures only for framistans; if you want to include your company’s business in selling gronespiels, you need to call Scotty; if you want to know if United Frabezoids ever got paid, you call Robin in accounts payable. The company as a whole is a large repository of information, with individual humans effectively playing the role of neural networks running specialized programs. No one person has all the knowledge, and indeed, no one person in a large company even knows whom to ask for every bit of knowledge it takes to keep the company running.

A typical story: Booz Allen Hamilton was given a big contract by the Fortune 100 company where Linda worked as the executive assistant to the CEO. Their assignment was to study the organization and make suggestions for structural improvement. While interviewing employees there, the Booz consultants discovered three highly trained data analysts with similar skill sets and similar mandates working in three entirely separate columns of the company’s org chart. Each data analyst reported to an assistant manager, who reported to a district manager, who reported to a division manager, who reported to a vice president. Each data analyst was ultimately responsible to an entirely different vice president, making it virtually impossible for them, their bosses, or even their bosses’ bosses to know about the existence of the others. (They even worked in different buildings.) Booz consultants were able to bring the analysts together for weekly meetings where they pooled their knowledge, shared certain tricks they had learned, and helped one another solve common technical problems they were facing. This led to great efficiencies and cost savings for the company.

Vertical structures are necessary when a high degree of control and direct supervision over employees are required. Nuclear power plants, for example, tend to have very tall vertical structures because supervision is extremely important—even a small error can result in a disaster. The vertical structure allows managers to constantly check and cross-check the work of lower-level managers to ensure that rules and procedures are followed accurately and consistently.

RBC Royal Bank of Canada is a $30 billion company, serving 18 million customers. Its corporate culture places a high value on mentorship, on managers developing subordinates, improving their chances of being promoted, and ensuring gender equity. Its vertical structure allows for close supervision of employees by their managers. Liz Claiborne, Inc., was the first Fortune 500 company to be founded by a woman. When Liz Claiborne was designing the structure of her company, she chose flat—four levels for four thousand employees—in order to keep the company nimble and able to respond quickly to changing fashion trends. There is no evidence that structure in and of itself affects the profitability of a company; different structures work best for different companies.

The size of an organization tends to predict how many levels it will have, but the relationship is logarithmic. That is, while an organization with 1,000 employees on average has four hierarchical levels, increasing the number of employees by a factor of 10 does not increase the number of levels by 10; rather, it increases the number of levels by a factor of 2. And after an organization reaches 10,000 employees, an asymptote is reached: Organizations with 12,000, 100,000, or 200,000 employees rarely have more than nine or ten levels in their hierarchy. The principle of minimum chain of command states that an organization should choose the fewest number of hierarchical levels possible.

These same descriptions of structure—flat and vertical—can be applied to a corporate website, or the file system on your own computer. Imagine that the flat and vertical structure drawings on page 273 are site maps for two different versions of a company’s website. Both sites might present visitors with the same data, but the visitors’ experience will be very different. With a well-designed flat organization, the visitor can obtain summary information in one click, and more detailed information in two clicks. With the vertical organization, that same visitor might also locate desired summary information in one or two clicks, but the detailed information will require four clicks. Of course sites aren’t always designed well or in a way that allows a visitor to find what she’s looking for—Web designers are not typical users, and the labels, menus, and hierarchies they use may not be obvious to anyone else. Hence the user may end up doing a great deal of searching, fishing, and backtracking. The flat organization makes it easier to backtrack; the vertical makes it easier to locate a hard-to-find file if the visitor can be sure she’s in the correct subnode. Still, there are limits to flat organizations’ ease of use: If the number of middle-level categories becomes too great, it takes too long to review them all, and because they themselves are not hierarchically organized, there can be redundancies and overlap. Visitors can easily become overwhelmed by too many choices—deep hierarchy offers fewer choices at once. The same analysis applies to the folders within folders on your hard drive.

But the organization of people is radically different from the organization of a website. Even in a deep vertical structure, people can and need to have agency from time to time. The lowliest transit worker sometimes needs to jump on the track to rescue a woman who fell; an investment bank secretary needs to be a whistle-blower; a mailroom worker needs to notice the disgruntled coworker who showed up with a rifle. All those actions fulfill a part of the company’s objectives—safety and ethical dealings.

In any hierarchically organized firm or agency, the task of carrying out the company’s objectives typically falls to the people at the lowest levels of the hierarchy. Cell phones aren’t built by the engineer who designed them or the executive who is in charge of marketing and selling them but by technicians on an assembly line. A fire isn’t put out by the fire chief but by the coordinated efforts of a team of firefighters on the street. While managers and administrators do not typically do the main work of a company, they play an essential role in accomplishing the company’s objectives. Even though it is the machine gunner and not the major who fights battles, the major is likely to have a greater influence on the outcome of a battle than any single machine gunner.

Decision-Making Throughout the Hierarchy

Anyone who has ever owned something of high value that needs repairs—a home or a car, for example—has had to contend with compromises and has seen how a management perspective is necessary to the decision-making process. Do you buy the thirty-year roof or the twenty-year roof? The top-of-the-line washing machine or the bargain brand? Suppose your mechanic tells you that you need a new water pump for your car and that, in descending order of price, he can install an original equipment manufacturer (OEM) part from the dealer, a functionally identical part from an overseas company, or a warrantied used part from a junkyard. He can’t make the decision for you because he doesn’t know your disposable income or your plans for the car. (Are you getting ready to sell it? Restoring it for entry in a car show? Planning to drive it through the Rockies next July, where the cooling system will be pushed to its limits?) In short, the mechanic doesn’t have a high-level perspective on your long-range plans for your car or your money. Any decision other than the OEM part installed by an authorized dealer is a compromise, but one that many people are willing to make in the interest of satisficing.

Standard models of decision-making assume that a decision maker—especially in economic and business contexts—is not influenced by emotional considerations. But neuroeconomics research has shown this is not true: Economic decisions produce activity in emotional regions of the brain, including the insula and amygdala. The old cartoon image of the angel on one shoulder and the devil on the other, giving competing advice to a flummoxed head in the middle, is apt here. Benefits are evaluated deep inside the brain, in a part of the striatum closest to your spine (which includes the brain’s reward center, the nucleus accumbens), while costs are simultaneously evaluated in the amygdala, another deep structure, commonly thought of as the brain’s fear center (the region responsible for the fight-or-flight response during threats to survival and other dangers). Taking in this competing information about costs and benefits, the prefrontal cortex acts as the decider. This isn’t the same thing as the experience we have of consciously trying to decide between two alternatives; decision-making is often very rapid, outside our conscious control, and involves heuristics and cognitive impulses that have evolved to serve us in a wide range of situations. The rationality we think we bring to decision-making is partly illusory.

Major decisions are usually not made by any one individual, nor by any easily defined group of individuals. They emerge through a process of vastly distributed discussion, consultation, and sharing of information. This is both a positive and a negative feature of large organizations. When they work well, great things can be accomplished that would be impossible for a small number of people to do: designing and building the Hoover Dam, the plasma TV, or Habitat for Humanity. As suggested at the beginning of this chapter, when communications or the exercise of competent and ethically based authority do not work well, or the optimal checks and balances aren’t in place, you end up with bridge collapses, Enron, or AIG.

In general, in a multilevel vertical organization, the chain of authority and direction travels downward with increasing specificity. The CEO may articulate a plan to one of his VPs; that VP adds some specificity about how best he thinks the plan can be accomplished and hands it to a division manager with experience and expertise in these sorts of operations. This continues on, down the line, until it reaches the individuals who actually do the work.

We see this in the organization of military authority. The general or commander defines a goal. The colonel assigns tasks to each battalion in his command; the major to each company in his battalion; the captain to each platoon in his company. Each officer narrows the scope and increases the specificity of the instructions he passes on. Still, the modern army gives a fair degree of situational control and discretion to the soldiers on the ground. Perhaps surprisingly, the U.S. Army has been among the organizations most adaptable to change, and has thought deeply about how to the apply findings of psychological science to organizational behavior. Its current policy strives to empower people throughout the chain of command, “allowing subordinate and adjacent units to use their common understanding of the operational environment and commander’s intent, in conjunction with their own initiative, to synchronize actions with those of other units without direct control from the higher headquarters.”

The value of limited autonomy and the exercise of discretion by subordinates is not a recent development in organizational strategy, for companies or for the military. Nearly one hundred years ago, the 1923 U.S. Army Field Service Regulations manual expected that subordinates would have a degree of autonomy in matters of judgment, stating that “an order should not trespass upon the province of a subordinate.”

Smooth operation within the military or a company requires trust between subordinates and superiors and an expectation that subordinates will do the right thing. The current edition of the U.S. Army Training Manual puts it this way:

Our fundamental doctrine for command requires trust throughout the chain of command. Superiors trust subordinates and empower them to accomplish missions within their intent. Subordinates trust superiors to give them the freedom to execute the commander’s intent and support their decisions. The trust between all levels depends upon candor. . . .

Army doctrine stresses mission command, the conduct of military operations that allows subordinate leaders maximum initiative. It acknowledges that operations in the land domain are complex and often chaotic, and micromanagement does not work. Mission command emphasizes competent leaders applying their expertise to the situation as it exists on the ground and accomplishing the mission based on their commander’s intent. Mission command fosters a culture of trust, mutual understanding, and a willingness to learn from mistakes. . . . Commanders . . . provide subordinates as much leeway for initiative as possible while keeping operations synchronized.

Superiors often resist delegating authority or decisions. They rationalize this by saying that they are more highly skilled, trained, or experienced than the subordinate. But there are good reasons for delegating decision-making. First, the superior is more highly paid, and so the cost of the decision must be weighed against the benefit of having such a high-paid individual make it. (Remember the maxim from Chapter 5: How much is your time worth?) Along the same lines, the superior has to conserve his time so that he can use it for making more important decisions. Secondly, subordinates are often in a better position to make decisions because the facts of the case may be directly available to them and not to the superior. General Stanley McChrystal articulated this with respect to his leadership during the United States–Iraq conflict:

In my command, I would push down the ability and authority to act. It doesn’t mean the leader abrogates responsibility but that the team members are partners, not underlings. They’d wake me up in the middle of the night and ask “Can we drop this bomb?” and I’d ask “Should we?” Then they’d say, “That’s why we’re calling you!” But I don’t know anything more than they’re telling me, and I’m probably not smart enough to add any value to the knowledge they already have from the field.

Steve Wynn’s management philosophy endorses the same idea:

Like most managers, I’m at the top of a large pyramidal structure, and the people who are below me make most of the decisions. And most of the time, the decisions that they make are of the “A or B” type: Should we do A or should we do B? And for most of those, the decision is obvious—one outcome is clearly better than the other. In a few cases, the people below me have to think hard about which one to do, and this can be challenging. They might have to consult with someone else, look deeper into the problem, get more information.

Once in a while a decision comes along where both outcomes look bad. They have a choice between A and B and neither one is going to be good, and they can’t figure out which one to choose. That’s when they end up on my calendar. So when I look at my calendar, if the Director of Food Services is on there, I know it’s something bad. Either he’s going to quit, or he’s got to make a decision between two very bad outcomes. My job when that happens is not to make the decision for them as you might think. By definition, the people who are coming to me are the real experts on the problem. They know lots more about it, and they are closer to it. All I can do is try to get them to look at the problem in a different light. To use an aviation metaphor, I try to get them to see things from 5,000 feet up. I tell them to back up and find out one truth that they know is indisputable. However many steps they might have to back up, I talk it over with them until they find the deep truth underlying all of it. The truth might be something like “the most important thing at our hotel is the guest experience,” or “no matter what, we cannot serve food that is not 100% fresh.” Once they identify that core truth, we creep forward slowly through the problem and often a solution will emerge. But I don’t make the decision for them. They’re the ones who have to bring the decision to the people under them, and they’re the ones who have to live with it, so they need to come to the decision themselves and be comfortable with it.

It is just as important to recognize the value of making difficult decisions when necessary. As former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg notes:

A leader is someone willing to make decisions. Politicians can get elected if voters think they will do things, even if they don’t support all those things. W [President George W. Bush] was elected not because everyone agreed with him but because they knew he was sincere and would do what he thought needed to be done.

Ethics necessarily come into play in corporate and military decision-making. What is good for one’s own self-interests, or the company’s interests, is not always consonant with what is good for the community, the populace, or the world. Humans are social creatures, and most of us unconsciously modify our behavior to minimize conflict with those around us. Social comparison theory models this phenomenon well. If we see other cars parking in a no-parking zone, we are more likely to park there ourselves. If we see other dog owners ignoring the law to clean up after their dogs, we are more likely to ignore it, too. Part of this comes from a sense of equity and fairness that has been shown to be innately wired into our brains, a product of evolution. (Even three-year-olds react to inequality.) In effect, we think, “Why should I be the chump who picks up dog poo when everyone else just leaves theirs all over the Boston Commons?” Of course the argument is specious because good behaviors are just as contagious as bad, and if we model correct behavior, others are likely to follow.

Organizations that discuss ethics openly, and that model ethical behavior throughout the organization, create a culture of adhering to ethical norms because it is “what everyone does around here.” Organizations that allow employees to ignore ethics form a breeding ground for bad behavior that tempts even the most ethically minded and strong-willed person, a classic case of the power of the situation overpowering individual, dispositional traits. The ethical person may eventually find him- or herself thinking, “I’m fighting a losing battle; there’s no point in going the extra mile because no one notices and no one cares.” Doing the right thing when no one is looking is a mark of personal integrity, but many people find it very difficult to do.

The army is one of the most influential organizations to have addressed this, and they do so with surprising eloquence:

All warfare challenges the morals and ethics of Soldiers. An enemy may not respect international conventions and may commit atrocities with the aim of provoking retaliation in kind. . . . All leaders shoulder the responsibility that their subordinates return from a campaign not only as good Soldiers, but also as good citizens. . . . Membership in the Army profession carries with it significant responsibility—the effective and ethical application of combat power.

Ethical decision-making invokes different brain regions than economic decision-making and again, because of the metabolic costs, switching between these modes of thought can be difficult for many people. It’s difficult therefore to simultaneously weigh various outcomes that have both economic and ethical implications. Making ethical or moral decisions involves distinct structures within the frontal lobes: the orbitofrontal cortex (located just behind the eyes) and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex just above it. These two regions are also required for understanding ourselves in relation to others (social perception), and the compliance with social norms. When damaged, they can lead to socially inappropriate behavior such as swearing, walking around naked, and saying insulting things to people right to their faces. Making and evaluating ethical decisions also involves distinct subregions of the amygdala, the hippocampus (the brain’s memory index), and the back portion of the superior temporal sulcus, a deep groove in the brain that runs from front to back behind the ears. As with economic decisions involving costs and benefits, the prefrontal cortex acts as the decider between the moral actions being contemplated.

Neuroimaging studies have shown that ethical behavior is processed in the same way regardless of whether it involves helping someone in need or thwarting an unethical action. In one experiment, participants watched videos of people being compassionate toward an injured individual, or aggressive toward a violent assailant. As long as the people in the video were behaving in an ethically appropriate and socially sanctioned way, the same brain regions were active in the participants who watched the videos. Moreover, such brain activations are universal across people—different people contemplating the same ethical acts show a high degree of synchronization of their brain activity; that is, their neurons fire in similar, synchronous patterns. The neuronal populations affected by this include those in the insula (mentioned above in the discussion of economic decision-making), our friend the prefrontal cortex, and the precuneus, a region at the top and back of the head associated with self-reflection and perspective taking, and which exists not just in humans but in monkeys.

Does this mean that even monkeys have a moral sense? A recent study by one of the leading scientists of animal behavior, Frans de Waal, asked just this question. He found that monkeys have a highly developed sense of what is and is not equitable. In one study, brown capuchin monkeys who participated in an experiment with another monkey could choose to reward only themselves (a selfish option) or both of them (an equitable, prosocial option). The monkeys consistently chose to reward their partner. And this was more than a knee-jerk response. De Waal found convincing evidence that the capuchins were performing a kind of moral calculation. When the experimenter “accidentally” overpaid the partner monkey with a better treat, the deciding monkey withheld the reward to the partner, evening out the payoffs. In another study, monkeys performed tasks in exchange for food rewards given by the experimenters. If the experimenter gave a larger reward to one monkey than another for the same task, the monkey with the smaller reward would suddenly stop performing the task and sulk. Think about this: These monkeys were willing to forgo a reward entirely (a tempting piece of food) simply because they felt the organization of the reward structure was unfair.

Those In Charge

Conceptions of leadership vary from culture to culture and across time, including figures as diverse as Julius Caesar and Thomas Jefferson, Jack Welch of GE and Herb Kelleher of Southwest Airlines. Leaders can be reviled or revered, and they gain followers through mandate, threat of punishment (economic, psychological, or physical), or a combination of personal magnetism, motivation, and inspiration. In modern companies, government, or the military, a good leader might be best defined as anyone who inspires and influences people to accomplish goals and to pursue actions for the greater good of the organization. In a free society, an effective leader motivates people to focus their thinking and efforts in ways that allow them to do their best and to produce work that pushes them to the highest levels of their abilities. In some cases, people so inspired are free to discover unseen talents and achieve great satisfaction from their work and their interactions with coworkers.

A broader definition of leadership promoted by Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner includes individuals who significantly affect the thoughts, feelings, or behaviors of a significant number of individuals indirectly, through the works they create—these can be works of art, recipes, technological artifacts and products . . . almost anything. In this conception, influential leaders would include Amantine Dupin (George Sand), Picasso, Louis Armstrong, Marie Curie, and Martha Graham. These leaders typically work outside of corporate structure, although like anyone, they have to work with big business at some contractual level. Nevertheless, they don’t fit the standard business-school profile of a leader who has significant economic impact.

Both kinds of leaders, those inside and outside the corporate world, possess certain psychological traits. They tend to be adaptable and responsive, high in empathy, and able to see problems from all sides. These qualities require two distinct forms of cognition: social intelligence and flexible, deep analytic intelligence. An effective leader can quickly understand opposing views, how people came to hold them, and how to resolve conflicts in ways that are perceived to be mutually satisfying and beneficial. Leaders are often adept at bringing people together—suppliers, potential adversaries, competitors, characters in a story—who appear to have conflicting goals. A great business leader uses her empathy to allow people or organizations to save face in negotiations so that each side in a completed negotiation can feel they got what they wanted (and a gifted negotiator can make each side feel they got a little bit more than the other party). In Gardner’s model, it is no coincidence that many great leaders are also great storytellers—they motivate others around them with a compelling narrative, one that they themselves embody. Leaders show greater integration of electrical activity in the brain across disparate regions, meaning that they use more of their brain in a better-orchestrated fashion than the rest of us. Using these measures of neural integration, we can identify leaders in athletics and music, and in the next few years, the techniques promise to be refined enough to use as screening for leadership positions.

Great leaders can turn competitors into allies. Norbert Reithofer, CEO of BMW, and Akio Toyoda, CEO of Toyota—clearly competitors—launched a collaboration in 2011 to create an environmentally friendly luxury vehicle and a midsize sports car. The on-again, off-again partnership and strategic alliance between Steve Jobs at Apple and Bill Gates at Microsoft strengthened both companies and allowed them to better serve their customers.

As is obvious from the rash of corporate scandals in the United States over the last twenty years, negative leadership can be toxic, resulting in the collapse of companies or the loss of reputation and resources. It is often the result of self-centered attitudes, a lack of empathy for others within the organization, and a lack of concern with the organization’s long-term health. The U.S. Army recognizes this in military and civic organizations as well: “Toxic leaders consistently use dysfunctional behaviors to deceive, intimidate, coerce, or unfairly punish others to get what they want for themselves.” Prolonged use of these tactics undermines and erodes subordinates’ will, initiative, and morale.

Leaders are found in all levels of the company—one doesn’t have to be the CEO to exert influence and affect corporate culture (or to be a storyteller with the power to motivate others). Again, some of the best thinking on the subject comes from the U.S. Army. The latest version of their Mission Command manual outlines five principles that are shared by commanders and top executives in the most successful multinational businesses:

- Build cohesive teams through mutual trust.

- Create shared understanding.

- Provide a clear and concise set of expectations and goals.

- Allow workers at all levels to exercise disciplined initiative.

- Accept prudent risks.

Trust is gained or lost through everyday actions, not through grand or occasional gestures. It takes time to build—coming from successful shared experiences and training—a history of two-way communication, the successful completion of projects, and achievement of goals.

Creating shared understanding refers to company management communicating with subordinates at all levels the corporate vision, goals, and the purpose and significance of any specific initiatives or projects that must be undertaken by employees. This helps to empower employees to use their discretion because they share in a situational understanding of the overriding purpose of their actions. Managers who hide this purpose from underlings, out of a misguided sense of preserving power, end up with unhappy employees who perform their jobs with tunnel vision and who lack the information to exercise initiative.

At McGill University, the dean of science undertook an initiative several years ago called STARS (Science Talks About Research for Staff). These were lunchtime talks by professors in the science department who described their research to the general staff: secretaries, bookkeepers, technicians, and the custodial staff. These jobs tend to be very far removed from the actual science. The initiative was successful by any measure—the staff gained an understanding of the larger context of what they were doing. A bookkeeper realized she wasn’t just balancing the books for any old research lab but for one that was on the cusp of curing a major disorder. A secretary discovered that she was supporting work that uncovered the cause of the 2011 tsunami and that could help save lives with better tsunami predictions. The effect of Soup and Science was that everyone felt a renewed sense of purpose for their jobs. One custodian commented later that he was proud to be part of a team doing such important work. His work improved and he began to take personal initiative that improved the research environment in very real and tangible ways.

The third of the army’s five command principles concerns providing a clear and concise expression of expectations and goals, the purpose of particular tasks, and the intended end state. This furnishes focus to staff and helps subordinates and their superiors to achieve desired results without extensive further instructions. The senior manager’s intent provides the basis for unity of effort throughout the larger workforce.

Successful managers understand that they cannot provide guidance or direction for all conceivable contingencies. Having communicated a clear and concise expression of their intent, they then convey the boundaries within which subordinates may exercise disciplined initiative while maintaining unity of effort. Disciplined initiative is defined as taking action in the absence of specific instructions when existing instructions no longer fit the situation, or unforeseen opportunities arise.

Prudent risk is the deliberate exposure to a negative outcome when the employee judges that the potential positive outcome is worth the cost. It involves making careful, calculated assessments of the upsides and downsides of different actions. As productivity expert Marvin Weisbord notes, “There are no technical alternatives to personal responsibility and cooperation in the workplace. What’s needed are more people who will stick their necks out.”

Some employees are more productive than others. While some of this variation is attributable to differences in personality, work ethic, and other individual differences (which have a genetic and neurocognitive basis), the nature of the job itself can play a significant role. There are things that managers can do to improve productivity, based on recent findings in neuroscience and social psychology. Some of these are obvious and well known, such as setting clear goals and providing high-quality, immediate feedback. Expectations need to be reasonable or employees feel overwhelmed, and if they fall behind, they feel they can never catch up. Employee productivity is directly related to job satisfaction, and job satisfaction in turn is related to whether employees experience that they are doing a good job in terms of both quality and quantity of output.

There’s a part of the brain called Area 47 in the lateral prefrontal cortex that my colleague Vinod Menon and I have been closely studying for the last fifteen years. Although no larger than your pinky finger, it’s a fascinating area just behind your temples that has kept us busy. Area 47 contains prediction circuits that it uses in conjunction with memory to form projections about future states of events. If we can predict some (but not all) aspects of how a job will go, we find it rewarding. If we can predict all aspects of the job, down to the tiniest minutiae, it tends to be boring because there is nothing new and no opportunity to apply the discretion and judgment that management consultants and the U.S. Army have justly identified as components to finding one’s work meaningful and satisfying. If some but not too many aspects of the job are surprising in interesting ways, this can lead to a sense of discovery and self-growth.

Finding the right balance to keep Area 47 happy is tricky, but the most job satisfaction comes from a combination of these two: We function best when we are under some constraints and are allowed to exercise individual creativity within those constraints. In fact, this is posited to be the driving force in many forms of creativity, including literary and musical. Musicians work under the very tight constraints of a tonal system—Western music uses only twelve different notes—and yet within that system, there is great flexibility. The composers widely regarded as among the most creative in musical history fit this description of balancing creativity within constraints. Mozart didn’t invent the symphony (Torelli and Scarlatti are credited with that) and The Beatles didn’t invent rock ’n’ roll (Chuck Berry and Little Richard get the credit, but its roots go back clearly to Ike Turner and Jackie Brenston in 1951, Louis Jordan and Lionel Hampton in the 1940s). It’s what Mozart and The Beatles did within the tight constraints of those forms, the enormous creativity and ingenuity they brought to their work, that pushed at the boundaries of those forms, leading to them being redefined.

But there is a critical point about differences between individuals that exerts arguably more influence on worker productivity than any other. The factor is locus of control, a fancy name for how people view their autonomy and agency in the world. People with an internal locus of control believe that they are responsible for (or at least can influence) their own fates and life outcomes. They may or may not feel they are leaders, but they feel that they are essentially in charge of their lives. Those with an external locus of control see themselves as relatively powerless pawns in some game played by others; they believe that other people, environmental forces, the weather, malevolent gods, the alignment of celestial bodies—basically any and all external events—exert the most influence on their lives. (This latter view is artistically conveyed in existential novels by Kafka and Camus, not to mention Greek and Roman mythology.) Of course these are just extremes, and most people fall somewhere along a continuum between them. But locus of control turns out to be a significant moderating variable in a trifecta of life expectancy, life satisfaction, and work productivity. This is what the modern U.S. Army has done in allowing subordinates to use their own initiative: They’ve shifted a great deal of the locus of control in situations to the people actually doing the work.

Individuals with an internal locus of control will attribute success to their own efforts (“I tried really hard”) and likewise with failure (“I didn’t try hard enough”). Individuals with an external locus of control will praise or blame the external world (“It was pure luck” or “The competition was rigged”). In school settings, students with a high internal locus of control believe that hard work and focus will result in positive outcomes, and indeed, as a group they perform better academically. Locus of control also affects purchasing decisions. For example, women who believe they can control their weight respond most favorably to slender advertising models, and women who believe they can’t respond better to larger-size models.

Locus of control also shows up in gambling behaviors: Because people with a high external locus of control believe that things happen to them capriciously (rather than being the agents of their own fortunes), they are more likely to believe that events are governed by hidden and unseen outside forces such as luck. Accordingly, they are likely to take more chances, try riskier bets, and bet on a card or roulette number that hasn’t come up in a long time, under the mistaken notion that this outcome is now due; this is the so-called gambler’s fallacy. They are also more likely to believe that if they need money, gambling can provide it.

Locus of control appears to be a stable internal trait that is not significantly affected by experiences. That is, you might expect that people who experience a great deal of hardship would give up any notions of their own agency in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary and become externals. And you might expect that those who experience a great deal of success would become internals, self-confident believers that they were the agents of that success all along. But the research doesn’t bear this out. For example, researchers studied small independent business owners whose shops were destroyed by Hurricane Agnes in 1972, at the time, the costliest hurricane to hit the United States. Over one hundred business owners were assessed for whether they tended toward internal or external locus of control. Then, three and a half years after the hurricane, they were reassessed. Many realized big improvements in their businesses during the recovery years, but many did not, seeing once thriving businesses deteriorate dramatically; many were thrown into ruin.

The interesting finding is that on the whole, none of these individuals shifted their views about internal versus external locus of control as a function of how their fortunes changed. Those who were internals to begin with remained internals regardless of whether their business performance improved or not during the intervening time. Same with the externals. Interestingly, however, those internals whose performance improved showed a shift toward greater internality, meaning they attributed the improvement to their hard work. Those who were externals and who experienced setbacks and losses showed a shift toward greater externality, meaning they attributed their failures to a deepening of the situational factors and bad luck that they felt they had experienced throughout their lives. In other words, a change of fortune following the hurricane that confirmed their beliefs only caused them to increase the strength of those beliefs; a change in fortune that went counter to their beliefs (an internal losing everything, an external whose business recovered) did nothing to change their beliefs.

The locus-of-control construct is measurable with standard psychological tests and turns out to be predictive of job performance. It also influences the managerial style that will be effective. Employees who have an external locus of control believe their own actions will not lead to the attainment of rewards or the avoidance of punishment, and therefore, they don’t respond to rewards and punishments the way others do. Higher managers tend to have a high internal locus of control.

Internals tend to be higher achievers, and externals tend to experience more stress and are prone to depression. Internals, as you might expect, exert greater effort to influence their environment (because, unlike externals, they believe their efforts will amount to something). Internals tend to learn better, seek new information more actively, and use that information more effectively, and they are better at problem solving. Such findings may lead managers to think they should screen for and hire only people with an internal locus of control, but it depends on the particular job. Internals tend to exhibit less conformity than externals, and less attitude change after being exposed to a persuasive message. Because internals are more likely to initiate changes in their environment, they can be more troublesome to supervise. Moreover, they’re sensitive to reinforcement, so if effort in a particular job doesn’t lead to rewards, they may lose motivation more than an external, who has no expectation that his or her effort really matters anyway.

Industrial organization scientist Paul Spector of the University of South Florida says that internals may attempt to control work flow, task accomplishment, operating procedures, work assignments, relationships with supervisors and subordinates, working conditions, goal setting, work scheduling, and organizational policy. Spector summarizes: “Externals make more compliant followers or subordinates than do internals, who are likely to be independent and resist control by superiors and other individuals. . . . Externals, because of their greater compliance, would probably be easier to supervise as they would be more likely to follow directions.” So the kind of employee who will perform best depends on the kind of work that needs to be done. If the job requires adaptability and complex learning, independence and initiative, or high motivation, internals would be expected to perform better. When the job requires compliance and strict adherence to protocols, the external would perform better.

The combination of high autonomy and an internal locus of control is associated with the highest levels of productivity. Internals typically “make things happen,” and this, combined with the opportunity to do so (through high autonomy), delivers results. Obviously, some jobs that involve repetitive, highly constrained tasks such as some assembly-line work, toll taking, stockroom, cashier, and manual labor are better suited to people who don’t desire autonomy. Many people prefer jobs that are predictable and where they don’t have to take personal responsibility for how they organize their time or their tasks. These workers will perform better if they can simply follow instructions and are not asked to make any decisions. Even within these kinds of jobs, however, the history of business is full of cases in which a worker exercised autonomy in a job where it was not typically found and came up with a better way of doing things, and a manager had the foresight to accept the worker’s suggestions. (The sandpaper salesman Richard G. Drew, who invented masking tape and turned 3M into one of the largest companies, is one famous case.)

On the other hand, workers who are self-motivated, proactive, and creative may find jobs with a lack of autonomy to be stifling, frustrating, and boring, and this may dramatically reduce their motivation to perform at a high level. This means that managers should be alert to the differences in motivational styles, and take care to provide individuals who have an internal locus of control with autonomous jobs, and individuals who have an external locus of control with more constrained jobs.

Related to autonomy is the fact that most workers are motivated by intrinsic rewards, not paychecks. Managers tend to think they are uniquely motivated by intrinsic matters such as pride, self-respect, and doing something worthwhile, believing that their employees don’t care about much other than getting paid. But this is not borne out by the research. By attributing shallow motives to employees, bosses overlook the actual depth of their minds and then fail to offer their workers those things that truly motivate them. Take the GM auto plant in Fremont, California. In the late 1970s it was the worst-performing GM plant in the world—defects were rampant, absenteeism reached 20%, and workers sabotaged the cars. Bosses believed that the factory workers were mindless idiots, and the workers behaved that way. Employees had no control over their jobs and were told only what they needed to know to do their narrow jobs; they were told nothing about how their work fit into the larger picture of the plant or the company. In 1982, GM closed the Fremont plant. Within a few months, Toyota began a partnership with GM and reopened the plant, hiring back 90% of the original employees. The Toyota management method was built around the idea that, if only given the chance, workers wanted to take pride in their work, wanted to see how their work fit into the larger picture and have the power to make improvements and reduce defects. Within one year, with the same workers, the plant became number one in the GM system and absenteeism dropped to below 2%. The only thing that changed was management’s attitude toward employees, treating them with respect, treating them more like managers treated one another—as intrinsically motivated, conscientious members of a team with shared goals.

Who was the most productive person of all time? This is a difficult question to answer, largely because productivity itself is not well defined, and conceptions of it change through the ages and over different parts of the world. But one could argue that William Shakespeare was immensely productive. Before dying at the age of fifty-two, he composed thirty-eight plays, 154 sonnets, and two long narrative poems. Most of his works were produced in a twenty-four-year period of intense productivity. And these weren’t just any works—they are some of the most highly respected works of literature ever produced in the history of the world.

One could also make a case for Thomas Edison, who held nearly eleven hundred patents, including many that changed history: electric light and power utilities, sound recordings, and motion pictures. He also introduced pay-per-view in 1894. One thing these two have in common—and share with other greats like Mozart and Leonardo da Vinci—is that they were their own bosses. That means to a large degree the locus of control for their activities was internal. Sure, Mozart had commissions, but within a system of constraints, he was free to do what he wanted in the way he wanted to do it. Being one’s own boss requires a lot of discipline, but for those who can manage it, greater productivity appears to be the reward.

Other factors contribute to productivity, such as being an early riser: Studies have shown that early birds tend to be happier, more conscientious and productive, than night owls. Sticking to a schedule helps, as does making time for exercise. Mark Cuban, the owner of Landmark Theatres and the Dallas Mavericks, echoes what many CEOs and their employees say about meetings: They’re usually a waste of time. An exception is if you’re negotiating a deal or soliciting advice from a large number of people. But even then, meetings should be short, drawn up with a strict agenda, and given a time limit. Warren Buffett’s datebook is nearly completely empty and has been for twenty-five years—he rarely schedules anything of any kind, finding that an open schedule is a key to his productivity.

The Paperwork

Organizing people is a good start to increasing value in any business. But how can the people—and that’s each of us—begin to organize the constant flood of documents that seem to take over every aspect of our work and our private lives? Managing the flow of paper and electronic documents is increasingly important to being effective in business. By now, weren’t we supposed to have the paperless office? That seems to have gone the way of jet packs and Rosie the Robot. Paper consumption has increased 50% since 1980, and today the United States uses 70 million tons of paper in a year. That’s 467 pounds, or 12,000 sheets, of paper for every man, woman, and child. It would take six trees forty feet tall to replenish it. How did we get here and what can we do about it?

After the mid 1800s, as companies grew in size, and their employees spread out geographically, businesses found it useful to keep copies of outgoing correspondence either by hand-copying each document or through the use of a protocopier called the letter press. Incoming correspondence tended to be placed in pigeonhole desks and cabinets, sometimes sorted but often not. Cogent information, such as the sender, date, and subject, might be written on the outside of the letter or fold to help in locating it later. With a small amount of incoming correspondence, the system was manageable—one might have to search through several letters before finding the right one, but this didn’t take too much time and could have been similar to the children’s card game Concentration.

Concentration is a game based on a 1960s television game show hosted by Hugh Downs. In the home version, players set up a matrix of cards facedown—perhaps six across and five down for a total of thirty cards. (You start with two decks of cards and select matched pairs, so that every card in your matrix has an identical mate.) The first player turns over two cards. If they match, the player keeps them. If they don’t, the player turns them back over, facedown, and it is the next player’s turn. Players who can remember where previously turned-over cards were located are at an advantage. The ability to do this resides in the hippocampus—remember, it’s the place-memory system that increases in size in London taxicab drivers.

All of us use this hippocampal spatial memory every day, whether trying to find a document or a household item. We often have a clear idea of where the item is, relative to others. The cognitive psychologist Roger Shepard’s entire filing system was simply stacks and stacks of paper all through his office. He knew which pile a given document was in, and roughly how far down into the pile it was, so he could minimize his search time using this spatial memory. Similarly, the early system of finding unsorted letters filed in cubbyholes relied on the office worker’s spatial memory of where that letter was. Spatial memory can be very, very good. Squirrels can locate hundreds of nuts they buried—and they’re not just using smell. Experiments show that they preferentially look for nuts that they buried in the places they buried them, not for nuts buried by other squirrels. Nevertheless, with any large amount of paperwork or correspondence, finding the right piece in the nineteenth century could easily become time-consuming and frustrating.

The cubbyhole filing system was among the first modern attempts to externalize human memory and extend our brains’ own processing capacity. Important information was written down and could then be consulted later for verification. The limitation was that human memory had to be used to remember where the document was filed.

The next development in the cubbyhole filing system was . . . more cubbyholes! The Wooton Desk (patent 1874) featured over one hundred storage places, and advertising promised the businessman he would become “master of the situation.” If one had the prescience to label the cubbyholes in an organized fashion—by client last name, by due date for order, or through some other logical scheme—the system could work very well.

But still the big problem was that each individual document needed to be folded to fit in the cubbyholes, meaning that it had to be unfolded to be identified and used. The first big improvement on this was the flat file, introduced in the late 1800s. Flat files could be kept in drawers, in bound book volumes, or in cabinets, and they increased search efficiency as well as capacity. Flat files were either bound or unbound. When bound, documents tended to be stored chronologically, which meant that one needed to know roughly when a document arrived in order to locate it. More flexible were flat files that were filed loosely in boxes and drawers; this allowed them to be arranged, rearranged, and removed as needed, just like the 3 x 5 index cards favored by Phaedrus (and many HSPs) in Chapter 2.

The state of the art for flat file storage by the late nineteenth century was a system of letter-size file boxes, similar to the kind still available today at most stationery stores. Correspondence could be sewn in, glued in, or otherwise inserted into alphabetical or chronological order. By 1868, flat file cabinets had been introduced—these were cabinets containing several dozen drawers of the dimensions of a flat letter, something like oversize library card catalogues. These drawers could be organized in any of the ways already mentioned, typically chronologically, alphabetically, or topically, and the contents of the drawers could be further organized. Often, the drawer contents were left unsorted, requiring the user to have to look through the contents to find the right document. JoAnne Yates, professor of management at MIT and a world expert in business communication, articulates the problems:

To locate correspondence in an opened box file or a horizontal cabinet file, all the correspondence on top of the item sought had to be lifted up. Since the alphabetically or numerically designated drawers in horizontal cabinet files filled up at different rates, correspondence was transferred out of active files into back-up storage at different rates as well. And the drawers could not be allowed to get too full, since then papers would catch and tear as the drawers were opened. Letter boxes had to be taken down from a shelf and opened up, a time-consuming operation when large amounts of filing were done.

As Yates notes, keeping track of whether a given document or pile of documents was deemed active or archival was not always made explicit. Moreover, if the user wanted to expand, this might require transferring the contents of one box to another in an iterative process that might require dozens of boxes being moved down in the cabinet, to make room for the new box.

To help prevent document loss, and to keep documents in the order they were filed, a ring system was introduced around 1881, similar to the three-ring binders we now use. The advantages of ringed flat files were substantial, providing random access (like Phaedrus’s 3 x 5 index card system) and minimizing the risk of document loss. With all their advantages, binders did not become the dominant form of storage. For the next fifty years, horizontal files and file books (both bound and glued) were the standard in office organization. Vertical files that resemble the ones we use today were first introduced in 1898. A confluence of circumstances made them useful. Copying technology improved, increasing the number of documents to be filed; the “systematic management movement” required increasing documentation and correspondence; the Dewey Decimal System, introduced in 1876 and used in libraries for organizing books, relied on index cards that were kept in drawers, so the furniture for holding vertical files was already familiar. The invention of the modern typewriter increased the speed at which documents could be prepared, and hence the number of them needing to be filed. The Library Bureau, founded by Melvil Dewey, created a system for filing and organizing documents that consisted of vertical files, guides, labels, folders, and cabinetry and won a gold medal at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago.

Vertical files function best when alphabetized. One factor that prevented their earlier invention was that, up through the eighteenth century, the alphabet was not universally known. The historian James Gleick notes, “A literate, book-buying Englishman at the turn of the seventeenth century could live a lifetime without ever encountering a set of data ordered alphabetically.” So alphabetizing files was not the first organizational scheme that came to mind, simply because the average reader could not be expected to know that H came after C in the alphabet. We take it for granted now because all schoolchildren are taught to memorize the alphabet. Moreover, spelling was not regarded as something that could be right or wrong until the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, so alphabetizing was not practical. The first dictionaries were faced with the puzzling problem of how to arrange the words.

When vertical files became the standard around 1900—followed by their offspring, the hanging file folders invented by Frank D. Jonas in 1941—they offered a number of organizational advantages that probably seem obvious to us now, but they were an innovation hundreds of years in the making:

- Papers could be left open and not folded, so their contents could be easily inspected.

- Handling and ease of access: Papers filed on edge were easier to handle; papers before them in the sequence didn’t have to be removed first.

- Papers that were related to one another could be kept in the same folder, and then subcategorized within the folder (e.g., by date, or alphabetically by topic or author).

- Whole folders could be removed from the cabinet for ease of use.

- Unlike the bound systems previously in use, documents could be taken out of the system individually, and could be re-sorted or refiled at will (the Phaedrus principle).

- When folders became full, their contents could be easily redistributed.

- The system was easily expandable.

- Transparency: If properly labeled and implemented, the system could be used by anyone encountering it for the first time.

Vertical files don’t solve every problem, of course. There is still the decision to make about how to organize the files and folders, not to mention how to organize drawers within a filing cabinet, and if you have multiple filing cabinets, how to organize them. Running a strictly alphabetical system across a dozen different cabinets is efficient if every folder is sorted by name (as in a doctor’s office), but suppose you’re filing different kinds of things? You may have files for customers and for suppliers, and it would be more effective to separate them into different cabinets.

HSPs typically organize their files by adopting a hierarchical or nested system, in which topic, person, company, or chronology is embedded in another organization scheme. For example, some companies organize their files first geographically by region of the world or country, and then by topic, person, company, or chronology.

How would a nested system look today in a medium-size business? Suppose you run an automotive parts company and you ship to the forty-eight states of the continental United States. For various reasons, you treat the Northeast, Southeast, West Coast, and “Middle” of the country differently. This could be because of differential shipping costs, or different product lines specific to those territories. You might start out with a four-drawer filing cabinet, with each of the drawers labeled for one of the four territories. Within a drawer, you’d have folders for your customers arranged alphabetically by customer surname or company name. As you expand your business, you may eventually need an entire filing cabinet for each territory, with drawer 1 for your alphabetical entries A–F, drawer 2 for G–K, and so on. The nesting hierarchy doesn’t need to stop there. How will you arrange the documents within a customer’s file folder? Perhaps reverse chronologically, with the newest items first.

If you have many pending orders that take some time to fill, you may keep a folder of pending orders in front of each territory’s drawer, filing those pending orders chronologically so that you can quickly see how long the customer who has been waiting the longest has been without their order. There are of course infinite variations to filing systems. Rather than file drawers for territory, with customer folders inside, you could make your top-level file drawers strictly alphabetical and then subdivide within each drawer by region. For example, you’d open up the A file drawer (for customers whose surnames or company names begin with A) and you would have drawer dividers inside, for the territorial regions of Northeast, Southeast, West Coast, and Middle. There is no single rule for determining what the most efficient system will be for a given business. A successful system is one that requires the minimum amount of searching time, and that is transparent to anyone who walks in the room. It will be a system that can be easily described. Again, an efficient system is one in which you’ve exploited affordances by off-loading as many memory functions as possible from your brain into a well-labeled and logically organized collection of external objects.

This can take many forms, limited only by your imagination and ingenuity. If you find you’re often confusing one file folder for another, make the folders different colors to easily distinguish them. A business that depends heavily on telephone or Skype calls, and has clients, colleagues, or suppliers in different time zones, organizes all the materials related to these calls in time-zone order so that it’s easy to see whom to call at which times of day. Lawyers file case material in numbered binders or folders that correspond to statute numbers. Sometimes simple and whimsical ordering is more memorable—a clothing retailer keeps files related to shoes in the bottom drawer, pants one drawer up, shirts and jackets above that, and hats in the top drawer.

Linda describes the particularly robust system that she and her colleagues used at an $8 billion company with 250,000 employees. Documents of different kinds were separated into designated cabinets in the executive offices. One or more cabinets were dedicated to personnel files, others for shareholder information (including annual reports), budgets and expenses for the various units, and correspondence. The correspondence filing was an essential part of the system.

The system for correspondence was that I would keep hard copies of everything in triplicate. One copy of a letter would go in a chronological file, one in a topic file, and one alphabetically by the name of the correspondent. We kept these in three-ring binders, and there would be alphabetical tabs inside, or for a particularly large or often-used section, a custom tab with the name of that section. The outside of the binder was clearly labeled with the contents.

In addition to the hard copies, Linda kept a list of all correspondence, with keywords, in a database program (she used FileMaker, but Excel would work as well). When she needed to locate a particular document, she’d look it up in her computer database by searching for a keyword. That would tell her which three binders the document was in (e.g., chron file for February 1987, topic binder for the Larch project, volume 3, or alpha binder by letter writer’s last name). If the computers were down, or she couldn’t find it in the database, it was nearly always found by browsing through the binders.

The system is remarkably effective, and the time spent maintaining it is more than compensated for by the efficiencies of retrieval. It cleverly exploits the principle of associative memory (the fire truck example from the Introduction, Robert Shapiro’s and Craig Kallman’s annotated contacts lists in Chapter 4), that memory can be accessed through a variety of converging nodes. We don’t always remember everything about an event, but if we can remember one thing (such as the approximate date, or where a given document fell roughly in sequence with respect to other documents, or which person was involved in it), we can find what we’re looking for by using the associative networks in our brains.

Linda’s decision to move correspondence to three-ring binders reflects a fundamental principle of file folder management: Don’t put into a file folder more than will fit, and generally not more than fifty pages. If your file folders contain more than that, experts advise splitting up the contents into subfolders. If you truly need to keep more pages than that in one place, consider moving to a three-ring binder system. The advantage of the binder system is that pages are retained in order—they don’t fall or spill out—and via the Phaedrus principle, they provide random access and can be reordered if necessary.

In addition to these systems, HSPs create systems to automatically divide up paperwork and projects temporally, based on how urgent they are. A small category of “now” items, things that they need to deal with right away, is close by. A second category of “near-term” items is a little farther away, perhaps on the other side of the office or down the hall. A third category of reference or archival papers can be even farther away, maybe on another floor or off-site. Linda adds that anything that needs to be accessed regularly should be put in a special RECURRENCE folder so that it is easy to get to. This might include a delivery log, a spreadsheet updated weekly with sales figures, or staff phone numbers.

—

An essential component of setting up any organizational system in a business environment is to allow for things that fall through the cracks, things that don’t fit neatly into any of your categories—the miscellaneous file or junk drawer, just as you might have at home in the kitchen. If you can’t come up with a logical place for something, it does not represent a failure of cognition or imagination; it reflects the complex, intercorrelated structure of the many objects and artifacts in our lives, the fuzzy boundaries, and the overlapping uses of things. As Linda says, “The miscellaneous folder is progress, not a step backward.” That list of frequent flyer numbers you constantly refer to? Put it in the RECURRENCE folder or a MISCELLANEOUS folder in the front of the drawer. Say you take a tour of a vacant office building across town. You’re not really looking to move, but you want to save the information sheet you received just in case. If your filing system doesn’t have a section for relocating, office lease, or physical plant, it would be wasteful to create one, and if you create a single file folder for this, with a single piece of paper in it, where will you file the folder?

Ed Littlefield (my old boss from Utah International) was a big proponent of creating a STUFF I DON’T KNOW WHERE TO FILE file. He’d check it once a month or so to refresh his memory of what’s in it, and occasionally he’d have accumulated a critical mass of materials with a theme to create a new, separate file for them. One successful scientist (and member of the Royal Society) keeps a series of junk drawer–like files called THINGS I WANT TO READ, PROJECTS I’D LIKE TO START, and MISCELLANEOUS IMPORTANT PAPERS. At home, that little bottle of auto body paint the shop gives you after a collision repair? If you keep a drawer or shelf for automotive supplies, that’s the obvious place to put it, but if you have zero automotive supplies except this little bottle, it doesn’t make sense to create a categorical spot just for one item. Better to put it in a junk drawer with other hard-to-categorize things.