Chapter 10Technology in the Daily Lives of Children and Teenagers

—

Killian Mullan

From the turn of the millennium, arguably one of the biggest and most rapid transformations in our daily lives relates to the use of technology and the internet. The development and rapid diffusion of powerful mobile devices has been one of the most dramatic changes in society over the past decade or so. The impact of this on children’s wellbeing and development continues to be a source of concern in some quarters. These concerns primarily relate to questions about the amount of time children spend using technology and the internet, and the impact of this on their time in other activities and social interactions. Parents naturally worry about the time their children spend using computers and mobile devices. They want to make sure their children are spending enough time doing homework, engaging in sports and creative activities, and interacting sociably with their family and friends. Concerns about the time that children spend using computers and mobile devices stem from the potential negative impact of how this affects time spent in other activities, such as sport, and social interaction. The generally accepted opinion is that excessive time using mobile devices has a negative effect on children’s social skills and wellbeing.1 Yet parents also recognize that children benefit from using technology for learning essential new skills, interacting with friends and family, and, importantly, for fun. National media routinely echo the concern that children spend too much time on their mobile devices2 (even while on holiday!3). Media reports sometimes centre on mobile devices, but often they focus on screen time in general, including time watching TV or gaming using computers. This is not surprising as children today can access media content, including video and music, as well as games and reading material, seamlessly across a range of devices (such as smartphones and tablets, but also ‘old’ desktop computers and new ‘smart’ TVs). Concerns about use of mobile devices and screen time therefore intersect with debates and concerns about children’s access to and use of the internet.

As children’s exposure to these technologies is relatively recent, our understanding of its consequences remains limited, and this opens up the potential for unfounded claims about its impacts. There is an urgent need for more evidence about how children are actually using computers and mobile devices, and how they have incorporated these devices into their daily lives. The UK 2014–15 TUS asked children to report on the time they spent using computers and mobile devices (smartphones and tablets), allowing us to consider a number of critical questions that relate directly to current debates about children’s use of technology and the internet, and its impact on their lives and development. Here we examine how children incorporate computers and mobile devices into their daily activities, and the social context within which they are using these technologies.

Children’s access to and use of computers, mobile devices and the internet

Over the past decade, children’s access to and use of the internet and mobile devices has increased dramatically. Ofcom reports that around two-thirds of children aged 8–15 had access to the internet at home in 2005, which rose to nine in every ten children by 2015.4 Smartphone ownership among children aged 8–11 rose from 13 per cent in 2010 to 24 per cent in 2015. Comparable figures for children aged 12–15 are 35 per cent and 69 per cent respectively, and research shows that children in the UK have a relatively high rate of smartphone ownership compared with children in other European countries.5 In addition, there have been markedly steep increases in children’s access to and ownership of tablet computers in the past five years. Ofcom report that around 5 per cent of children aged 5–15 had access to a tablet computer in 2010, which increased to 80 per cent in 2015, and ownership rose from 2 per cent to 40 per cent over the same period.

Sonia Livingstone and colleagues have studied in detail children’s (aged 9–16) use of mobile devices and computers to access the internet in the Net Children Go Mobile study.6 They found that the most common device children use to access the internet was a smartphone, with 56 per cent of children using them to go online. Perhaps surprisingly, girls and boys differed little in terms of accessing the internet with other mobile devices and computers.7 There were, however, very strong differences in the propensity to access the internet related to children’s ages, with older children being more likely to use mobile devices and computers to access the internet than younger children. For example, only 37 per cent of children aged 9–10 used mobile devices and computers to access the internet versus 97 per cent of teenagers aged 15–16. These differences are likely to reflect age differences in children’s ownership of devices, including smartphones, as noted above.

Debates on children’s time using technology and the internet

The proliferation of computers and mobile devices has given rise to much public debate and controversy about their impact on the lives and development of children. Some argue that children’s use of computers and mobile devices engenders a sedentary screen-based lifestyle that is harmful to their physical and mental health.8 They argue that computers and mobile devices expose children to new online risks, and that excessive amounts of time in sedentary screen-based activities come at the expense of time children could be spending in physical activity including outdoor play. Others counter that evidence that children’s use of technology and the internet has a negative impact is not conclusive, and that guidelines for children’s use of technology must rest on a strong evidence base that is still lacking.9

At the core of these debates is an unease, experienced by many parents, that children are spending excessive amounts of time using computers and mobile devices. It doesn’t help, though, that exactly what constitutes excessive is far from clear. There are no clear guidelines in the UK, and little evidence that anyone follows such guidelines internationally, or that they are even useful.10 A more basic question, however, has to do with how good we think our measures of children’s time using technology and the internet actually are. Many stories in the media about children’s time using technology report on measures of time use that are unreliable.11 For example, Ofcom’s measure of the time children spend using the internet,12 routinely cited in negative media reports, uses a question asking children to recall how many hours they spend using the internet on a typical day.13 Unfortunately, in general, we do not have a great ability to recall accurately how much time we spend in many of our routine daily activities.14 In addition, there is no reason why we should restrict measures of children’s time using the internet to a ‘typical’ day. In contrast, all-purpose time-use surveys provide reliable measures of how we spend our time in various activities. Therefore, the first major contribution of this chapter is simply to provide a reliable measure of the time children spend using devices.

A second related aspect of debates on children’s use of technology stems from its potential negative impact on the time they have available for other activities. However, there is no consistent evidence that screen time displaces time in other activities such as sport. Against a backdrop where children’s use of technology is continuing to evolve rapidly, we need to know more than we do currently about how children have integrated technology into their daily lives. Along with information about the time spent using devices, the UK TUS provides information on the main activities they are engaging in while using these devices. By studying what children are doing when they report using devices we explore the different ways in which the use of technology and the internet have become embedded in the daily lives of children.

A third issue in debates about children’s use of technology highlights its potential influence on the nature and quality of children’s social interactions. At the extreme, worries here centre on the image of a socially isolated, and perhaps introverted, child whose social interactions are mediated largely through technology, via social media or internet forums. In fact, research suggests that rather than replacing face-to-face social interactions, children and teenagers use technology in ways that facilitate and sustain interpersonal relationships.15 The important point perhaps is that technology is changing the nature of social interactions for children, in both positive and negative ways.16 The third focus of this chapter is therefore on the wider social context within which children use technology and the internet. Based on the information that children provide about the people they are spending time with throughout the day, we analyse how much time they spend alone, with family, and with others they know, when they are using devices. The chapter uses data from 1,171 children and young people aged 8–18, living with their parents and in education, and who each provided time-use data for up to two diary days.17

An overview of children’s time using computer devices

Table 10.1 shows that the vast majority of children (82.2 per cent) report using computers and mobile devices at some point during the day. On average, children aged 8–18 spend 2 hours 46 minutes per day using devices (around 20 hours per week18). There is very little difference between boys and girls aged 8–18 in their overall use of computers and mobile devices. Boys spent only slightly more time using devices than girls, but the difference is not significant.

Table 10.1 Children’s use of computers and mobile devices, UK (2015)

| Per cent using device daily | Average time per day (hrs:mins) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All (n=2,285) | 82.2 | 2:46 | |

| Gender | Boys (n=1,092) | 82.5 | 2:50 |

| Girls (n=1,193) | 82.0 | 2:42 | |

| 8–11 (n=889) | 71.2 | 1:30 | |

| Age | 12–15 (n=857) | 86.3 | 3:11 |

| 16–18 (n=539) | 91.7 | 3:55 |

In contrast to gender, there are pronounced age differences in children’s device use. Just over 70 per cent of children aged 8–11 report using a device at least once per day, which increases to 86.3 per cent of children aged 12–15, and increases further to 91.7 per cent of children aged 16–18. Reflecting this, the average time children spend using devices increases substantially with age, rising from 1 hour 30 minutes for children aged 8–11 (around 11 hours per week) to just under 4 hours for teenagers aged 16–18 (close to 28 hours per week). There were no significant gender differences within specific age groups. These results for gender and age are consistent with the findings of Livingstone and her colleagues in showing that girls and boys differ little, but that there are large age differences in children’s use of computers and mobile devices.

The distribution of time using computers and mobile devices

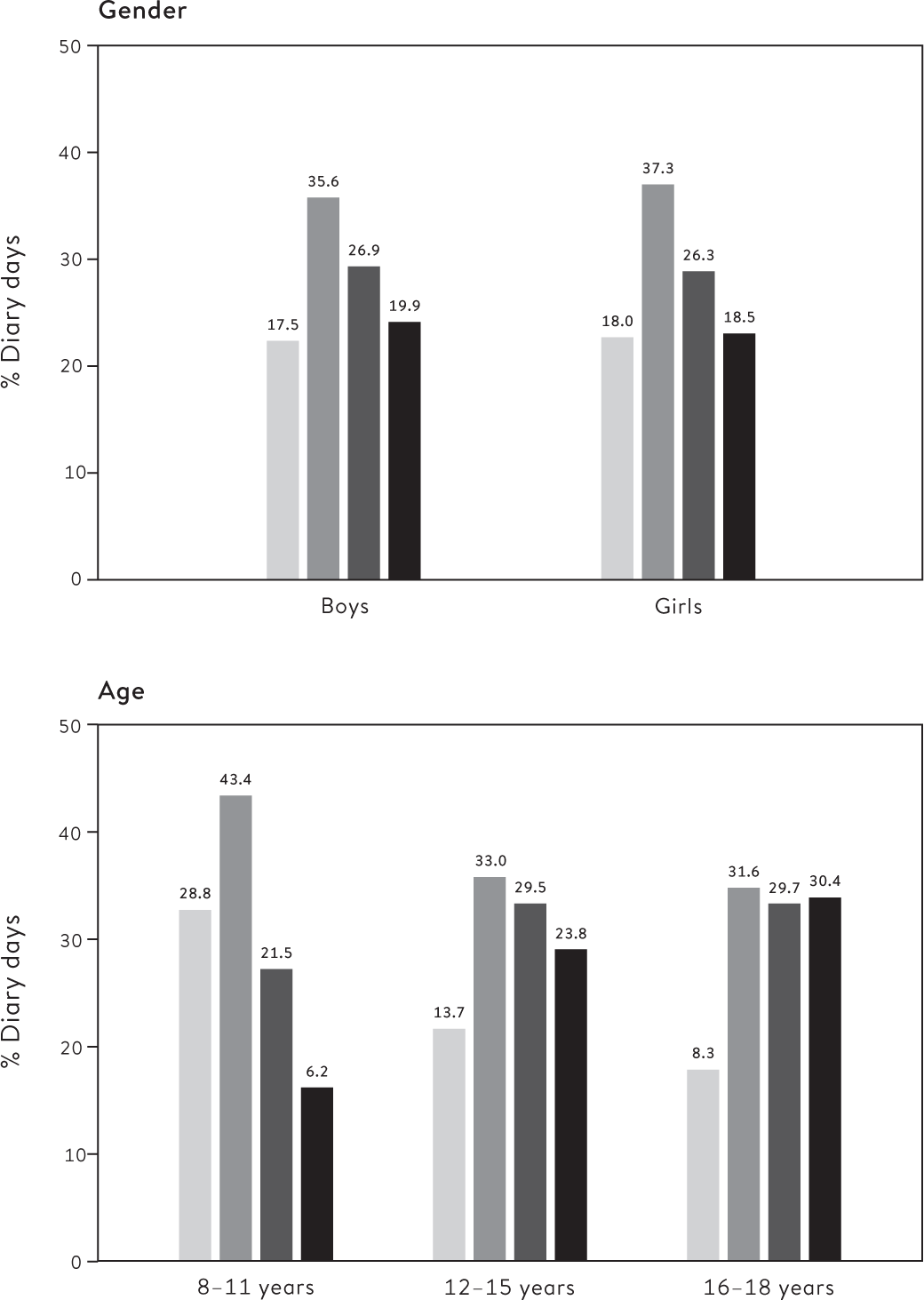

Averages can mask considerable variation in the quantity of time children spend using computers and mobile devices on a given day. To gain a better understanding of the full range of time children spend using devices on any given day, we divide children into four groups: those who report 1) no time using a device; 2) up to 2 hours using a device; 3) 2–5 hours using a device; and 4) 5 or more hours using a device. Figure 10.1 shows the distribution of UK children’s time using devices on a given day for boys and girls (upper panel), and for children in different age groups (lower panel). It shows that the distribution of the time boys and girls spend using devices is very similar (Figure 10.1, upper panel), echoing the results for the overall averages reported in Table 10.1. Around one third report using devices for up to 2 hours per day, just over one quarter of boys and girls report using devices for 2–5 hours, and just less than one fifth use devices for 5 or more hours on a given day.

Figure 10.1 Distribution of children’s time using devices by gender and age, UK (2015)

None

None

Up to 2 hours

Up to 2 hours

2–5 hours

2–5 hours

5 hours or more

5 hours or more

On the other hand, there are clear age differences in the distribution of children’s time using devices. Close to three-quarters of children aged 8–11 report, at most, 2 hours of time throughout the day using computer devices (including those who do not report any time using a device). This proportion falls to just under 50 per cent of children aged 12–15, and falls again to around 40 per cent for those aged 16–18. Conversely, the proportion of children reporting more than 2 hours using a device increases with age. The proportion of children who spend 2–5 hours using devices increases from 21.5 per cent for children aged 8–11 to around 30 per cent for children aged 12–15 and 16–18. However, the increase in the proportion of children reporting 5 or more hours is particularly striking, rising from around 6 per cent for children aged 8–11 to 30 per cent for teenagers aged 16–18.

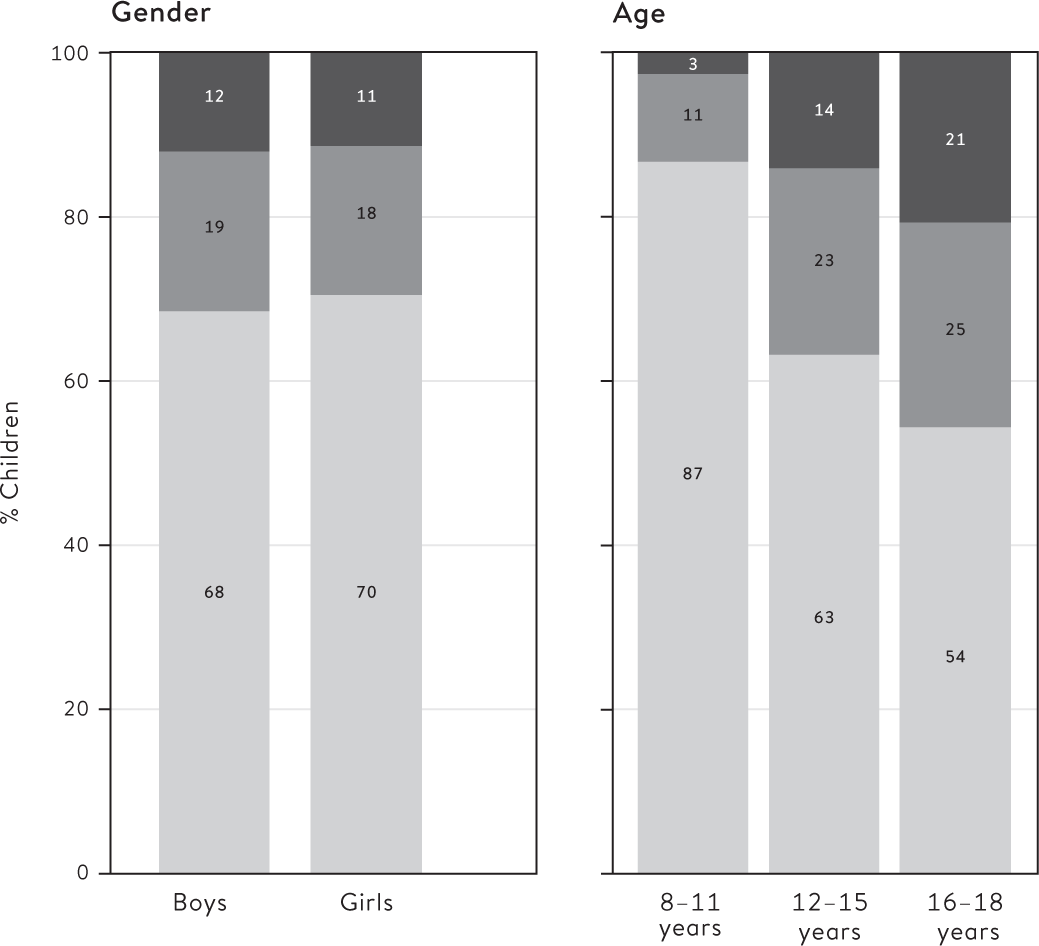

Overall, just over 10 per cent of children report using a device for 5 or more hours on both their diary days (see Figure 10.2). Again, there is no difference between boys and girls, but the proportion of children who report using a device for 5 or more hours on both diary days increases substantially with age. Only 3 per cent of children aged 8–11 report using a device for 5 or more hours on both diary days, rising to 21 per cent for children aged 16–18. It is likely that if we had data for more days the proportion of children who report large amounts of time using devices every day would be even lower.

Figure 10.2 Number of days that children report 5 or more hours using a device by gender and age, UK (2015)

5+ hours: 2 days

5+ hours: 2 days

5+ hours: 1 day

5+ hours: 1 day

5+ hours: no days

5+ hours: no days

Children’s activities when using computer devices

Previous research tells us much about what children are doing with the devices, such as playing games, listening to music, streaming video, or using social media.19 What is missing, however, is an understanding of the extent to which they use devices when engaging in different activities. We see increasingly, for example, that children as well as adults are using mobile devices at the dinner table while eating, in the car while travelling, and when engaging in many other activities. The TUS provides a unique insight into the way in which children incorporate technology into their daily activities.

As noted above, one of the major concerns about children’s use of technology and the internet is that it might be crowding out time spent on other important activities. We can examine this in two ways. One way is simply to examine how much of the time reported using devices corresponds with time when children’s main activity is using computers, as opposed to when engaging in other activities (e.g. eating or travelling). Another is to look at the total time spent in different activities and examine the amount of time during which children also report using a device.

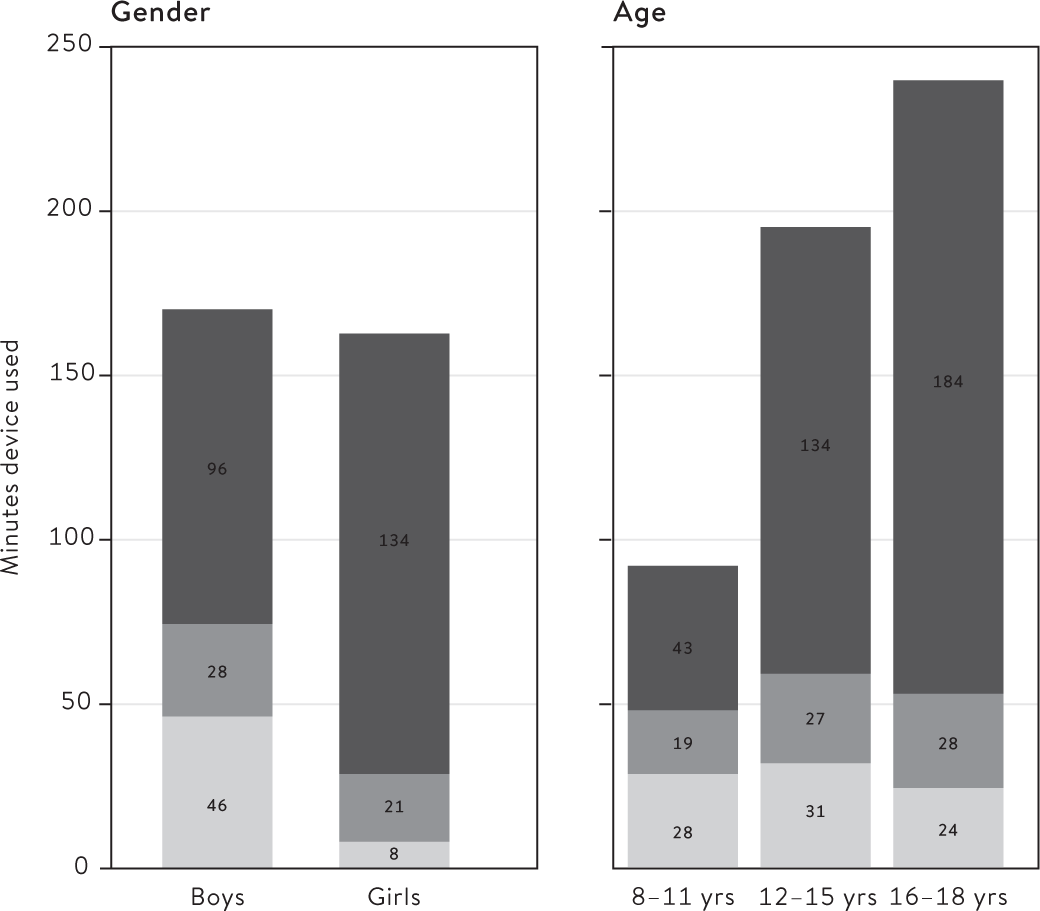

Firstly, to obtain the overall picture we look at the composition of all time using a device according to whether or not children report using computers as their main activity, or some other main activity. We distinguish between using computers for games and other times using computers such as browsing the internet, sending emails, or other activities. Figure 10.3 provides a breakdown of boys’ and girls’ total time using a device (left panel) and for children in different age groups (right panel) according to what they report doing as their main activity.

Although there was no difference in boys’ and girls’ overall time using devices (see Table 10.1), there are clear gender differences in the main activities children report while using devices. Boys spend 46 minutes playing computer games while reporting using a device compared with 8 minutes for girls, and this held across all age groups. Boys also spend a small amount more time than girls using computers as their main activity (28 mins v. 21 mins). Taken together, for around 44 per cent of boys’ total time using a device, they report playing video games and using computers as their main activity, compared with 18 per cent for girls. Consequently, girls spend most of their total time using a device, in both absolute and proportionate terms, while they report a main activity other than using computers. These findings echo those from research showing that boys are more likely to use devices for games, whereas girls’ spread their device use across a wide range of other activities such as streaming video, listening to music and using social media,20 which can be more readily combined with time engaging in other activities.

In relation to patterns for children in different age groups, the right panel of Figure 10.3 shows the composition of time in different activities when using a device for children aged 8–11, 12–15 and 16–18. Children aged 8–11 spend 28 minutes playing computer games and 19 minutes using computers for other purposes (including the internet) while reporting using a device. This comprises just over half (52 per cent) of all time children aged 8–11 use a device. In absolute terms the average time children spend using computers as their main activity (both for games and for other purposes) when they report using a device is very similar for older children aged 12–15 and 16–18. However, as the total time using a device increases substantially with age, in proportionate terms time using computers as a main activity (both for games and other purposes) when reporting using a device decreases to 30 per cent of all time using a device for children aged 12–15, and to 22 per cent for older teenagers (aged 16–18). Inversely, time in other activities when reporting using a device increases with age.

Figure 10.3 Children’s time using a device by gender and age, UK (2015)

Other time using device

Other time using device

Internet (other computer)

Internet (other computer)

Computer games

Computer games

Figure 10.4 shows that the composition of time using a device is relatively similar for children who report using devices for varying amounts of time during the day. Note particularly that the percentage of time spent using devices (right-hand panel) for those who use devices heavily (5 or more hours per day) is not concentrated in using computers as the main activity. Children’s use of devices is, rather, spread across many other activities, which we consider now in more detail.

Incorporating device use into key activities

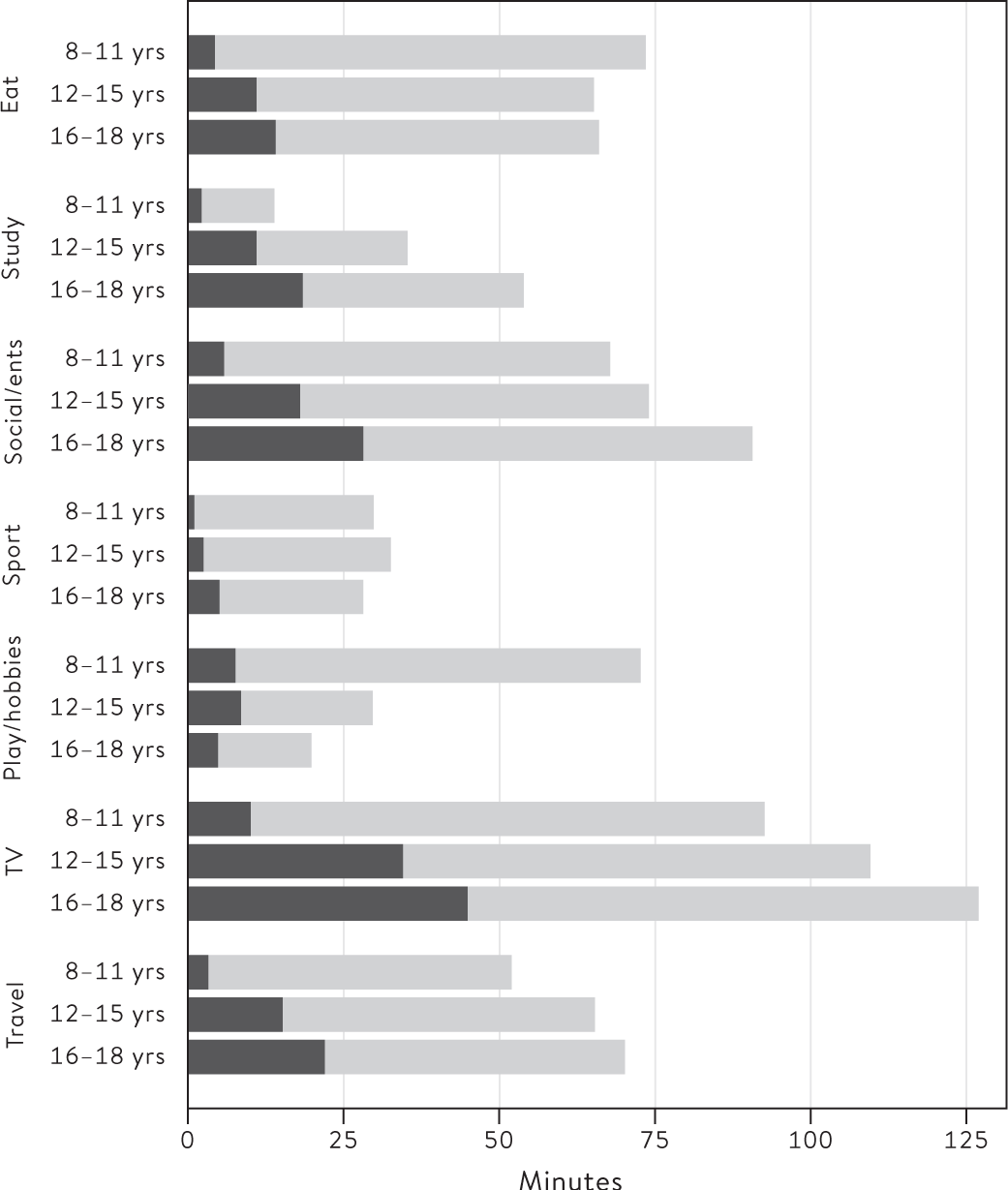

We illustrate here how children incorporate the use of devices into the time they spend in the following key activities: 1) eating; 2) study; 3) social/entertainment; 4) sport; 5) play/hobbies; 6) TV; and 7) travel. These activities comprise three-quarters of all other time spent using a device when children are not using a computer as a main activity (for games or other purposes). We deconstruct the time children spend in these key activities into time when they are engaging in the activity with a device, and time when they are engaging in the activity without a device. While previous research has focused on what children are using devices for, the results presented here complement this by shedding light on the proportion of time that children incorporate device use while engaging in a number of key daily activities.

Figure 10.4 Children’s time using a device: usage levels, UK (2015)

Other time using device

Other time using device

Internet (other computer)

Internet (other computer)

Computer games

Computer games

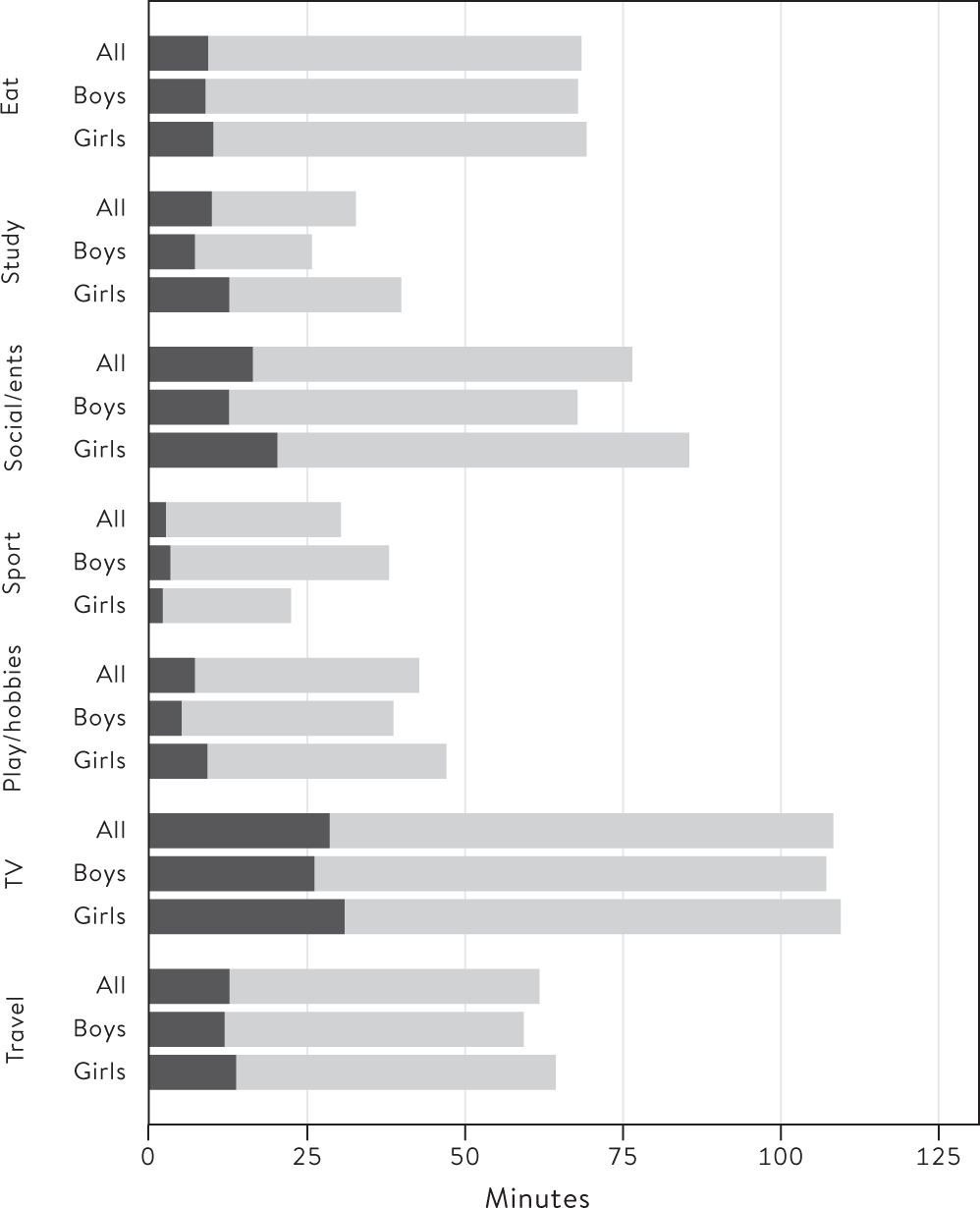

Table 10.2 shows the average time children spend in these activities when reporting using and not using devices, and the proportion of the total time in these activities during which device use is reported. The extent to which children incorporate device use into their daily activities varies from 10 per cent of the total time in sport (3 minutes), to 27 per cent of all time watching TV (29 minutes), and around 30 per cent of all time studying (10 minutes).21 Children report using devices for on average about one fifth of the total time they spend in social and entertainment activities (16 minutes), and the time they spend travelling (13 minutes).

Figure 10.5 shows that there are differences between boys and girls in how they incorporate device use into these activities. Proportionately (and in absolute terms) slightly more of girls’ time studying is carried out when they also report using a device. Girls use a device when studying for an average of 13 minutes, which is about one third of their total time studying (40 minutes). In absolute terms, girls spend twice as much time as boys who average 7 minutes studying while using a device, though girls spend more time studying overall. Girls also report using a device for a higher proportion of their total time in social/entertainment activities, and time in play/games. Girls and boys are similar in terms of how they incorporate device use into time eating, doing sport, watching TV and travelling. Therefore, although much more of girls’ time using a device is when they are engaging in other activities (Figure 10.3), this time spreads roughly evenly across a wide range of different activities.

Table 10.2

Children’s time in key activities when using and not using devices, UK (2015)

| Activities | Using device | Not using device | Total | Per cent total time using device |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eating | 0:10 | 0:59 | 1:09 | 14 |

| Study | 0:10 | 0:23 | 0:33 | 30 |

| Social/entertainment | 0:16 | 1:00 | 1:16 | 21 |

| Sport | 0:03 | 0:28 | 0:31 | 10 |

| Play/hobbies | 0:07 | 0:36 | 0:43 | 16 |

| TV | 0:29 | 1:20 | 1:49 | 27 |

| Travel | 0:13 | 0:49 | 1:02 | 21 |

Note: Excludes time using computers, personal care, paid work, housework, civic activities and non-reported activities

Figure 10.5 Children’s time using and not using devices in seven key activities: boys and girls aged 8–18, UK (2015)

Using device

Using device

Not using device

Not using device

We have already seen that as children get older they spend more time using devices, and that for proportionately less of this time they report using computers as their main activity. Not surprisingly therefore, as shown in Figure 10.6, as children get older they increasingly incorporate the use of devices into the time they spend in the activities considered here. The total time that children spend studying, socializing, watching TV and travelling increases with age, but these age-related patterns differ across activities depending on whether children also report using a device or not. Study time increases both for time spent studying while children report using a device and while they do not. Children aged 8–11 spend on average 14 minutes studying compared with 54 minutes for those aged 16–18. Time studying while reporting using a device increases from 2 minutes for children aged 8–11 to 18 minutes for children aged 16–18 (34 per cent of all time studying for this age group). In contrast, age-related increases of total time in social activities, TV and travel are concentrated in time when children also report using a device. Time playing games and engaging in hobbies declines substantially among children in secondary school (aged 12 and over) compared with children aged 8–11, but time using a device during these activities is relatively similar across age groups. The nature of this activity likely varies widely across age groups. Proportionally, more of older children’s time eating is reported with a device, as a result of both spending more time reporting using a device when eating, combined with slightly less time eating over all. Lastly, children’s average time in sport is very similar across age groups, being slightly lower among those aged 16–18 (28 minutes) compared with children aged 12–15 (32 minutes) and children aged 8–11 (30 minutes). Older children spend more time using a device when engaging in sport than younger children, however.

Figure 10.6 Children’s time using and not using devices in seven key activities by age group, UK (2015)

Not using device

Not using device

Using device

Using device

The social context of children’s computer device use

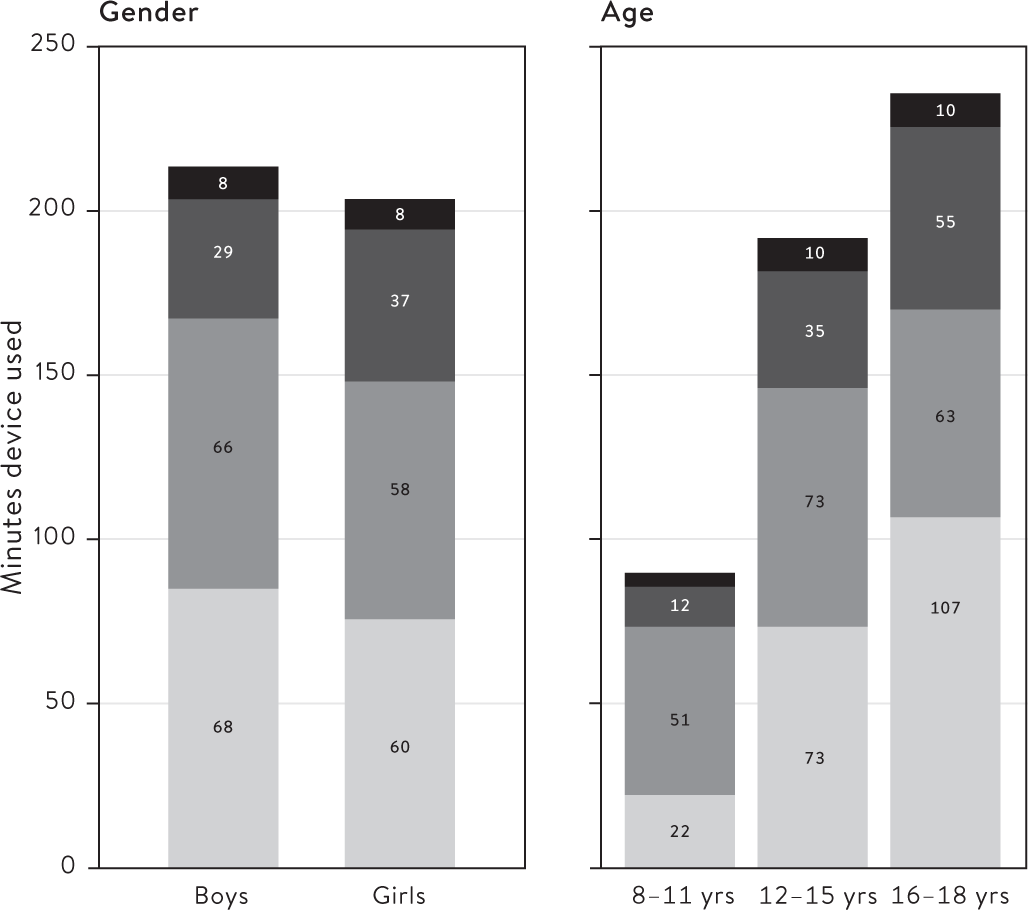

The time we spend using computers and mobile devices can often appear to be solitary, with all our attention focused on the device screen. Increasingly, we seem to spend time ‘together but not together’, with each one absorbed in her/his device. For children, the concern is that increasing amounts of time using devices is associated with less time in face-to-face social interactions with others, leading to diminished social and emotional wellbeing. Research suggests that this is not the case, but we know very little about the social context of children’s device use. To redress this, we examined who children reported being co-present with when they are using a device. Figure 10.7 shows the composition of children’s time using devices when alone, with family and with others who are known to them. The left panel compares boys and girls, and the right panel compares children in different age groups.

For around one hour of both boys’ and girls’ time using a device they report being alone, and for a further hour they report being with their family. They spend about 30 minutes with others they know when using a device, while co-presence data is not reported for just under 10 minutes of time using a device. Therefore, for the majority of time children report using devices, they are in the company of others (either family or others they know). Nevertheless, they are on their own for a substantial minority of the amount of the time they spend using a device, comprising about 40 per cent of the total. Children aged 8–11 spend an average of 20 minutes using a device while alone, which is one quarter of their total time using devices. Children aged 12–15 spend over an hour using devices alone (73 minutes), while teenagers aged 16–18 spend almost 2 hours using devices while alone (107 minutes). The proportion of all time using a device when children report being alone increases also, rising to 38 per cent for children aged 12–15, and 45 per cent for teenagers aged 16–18. This means that even though time alone with a device increases with age, it is still the case that most time using a device is when children report being in the presence of others. For younger children this time is skewed towards being with parents and other family members. For older teenagers aged 16–18 this time is balanced relatively evenly between time spent with co-resident family members, and time with friends and others they know outside the household.

Figure 10.7 The social context of time using computer devices by gender and age, UK (2015)

Not reported

Not reported

Family

Family

Others you know

Others you know

Alone

Alone

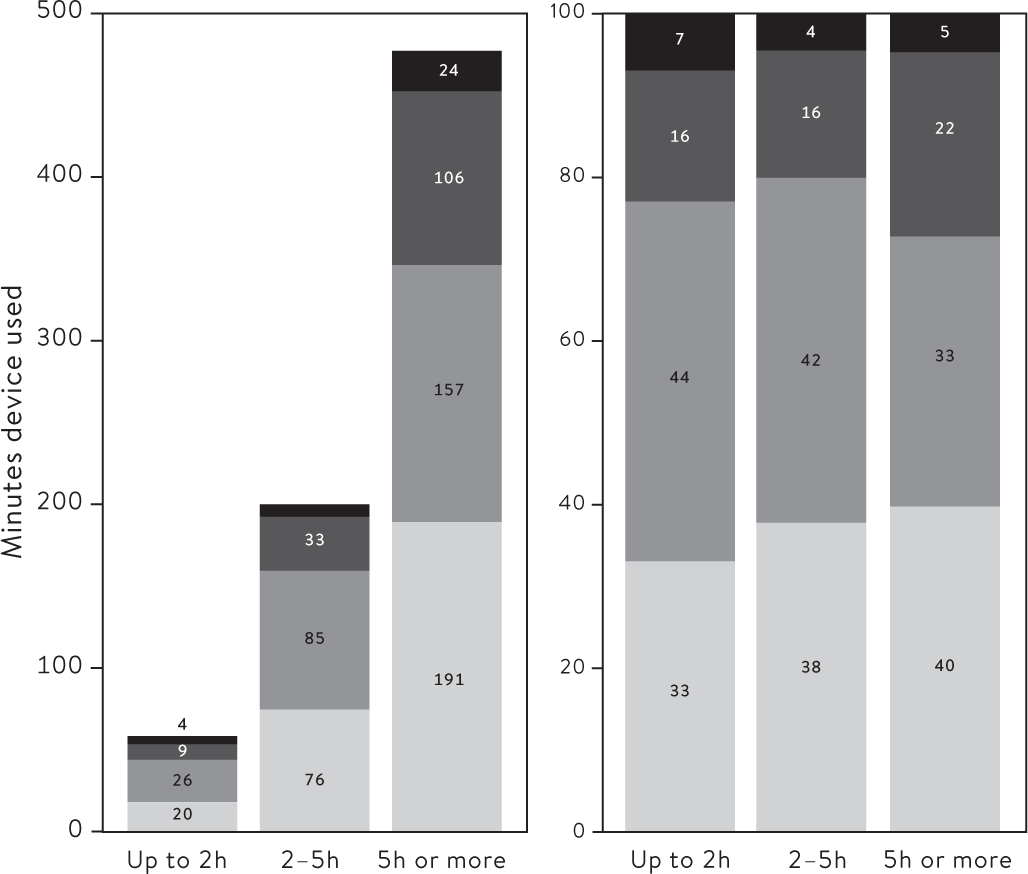

Lastly, Figure 10.8 shows the same analysis across different levels of device usage time. Here we ask whether those who use their devices more spend more or less time alone than others. It turns out that, although time alone when using a device increases across different levels of device usage, time alone as a proportion of all time using a device is relatively stable across different levels of device usage. Those who report up to 2 hours of device use spend on average one third of all time using a device alone (20 minutes). This increases to 38 per cent for children who use devices for 2–5 hours (76 minutes) and 40 per cent of all time using a device for children using devices for 5 or more hours (191 minutes). Therefore, the majority of time using a device is spent when co-present with others across the entire distribution of time that children spend using computers and mobile devices.

Figure 10.8 The social context of time using computer devices by usage levels, UK (2015)

Not reported

Not reported

Family

Family

Others you know

Others you know

Alone

Alone

To sum up, there is no doubt that many children spend a substantial amount of time using computers and mobile devices on a daily basis. However, our results show that previous estimates of younger children’s time using technology and the internet are overstated. Children aged 8–11 spent 1 hour and 30 minutes on average per day, almost half the amount cited in some media reports about children’s time using the internet.22 Only around 6 per cent of younger children’s diaries contained reports of 5 or more hours per day using devices, and less still (3 per cent) reported spending this amount of time using devices on two diary days. We found, in line with previous research, that boys and girls spent similar amounts of time using devices, but that this time increased substantially with the age of children. Teenagers aged 16–18 spent close to 30 hours per week using devices, and one in five older teenagers reported using 5 or more hours using devices on both diary days.

This level of usage begs the question about the impact of time using devices on time in other activities. We show here for the first time how children are incorporating their use of computers and mobile devices into their time across a broad range of different activities. The first key point is that the majority of time spent using devices is time when children do not report ‘using computers’ as their main activity. This is especially so for girls, and for older children. Looking closer at different types of activities, we found that children incorporated device use into a range of activities including eating, studying, social activities, watching TV and travelling. Girls spent more time using devices while studying and in social activities, though they spent more time in these activities overall. Although we are not able to explore this distinction in detail, devices might well be used in conjunction with the main activity (e.g. to watch TV, or for study purposes), or they could be facilitating a secondary activity (e.g. watching TV on a device while travelling, using a device to listen to music while studying).

With respect to the social context of children’s time using devices, we found that children reported being alone for a sizeable minority of their total time using a device. However, time spent using a device with family and with others outweighed time alone with a device, most notably for younger children. Although this doesn’t give us direct information on the nature of children’s social interactions (they could report being with family though not interacting with them, for example), these findings do provide something of a bulwark against exaggerated claims about social isolation arising from children’s time using computers and mobile devices. It’s also important to bear in mind that technology and the internet are altering the nature of our social interactions, and consequently our understanding of the character of time alone, and time spent ‘with’ others.

What is emerging from research on the relationship between technology and its potential impacts on children does not in general suggest that there is a straightforward direct negative link. Increasingly, the debate is shifting towards trying to get a clearer picture of the substance and context of children’s time using technology and the internet. This chapter has revealed that younger children are not spending as much time using computers and mobile devices as previous reports suggest, and highlights the fact that children’s time using devices varies from day to day. In addition, while children do indeed spend substantial amounts of time using computers and mobile devices, it is not confined to time that they are alone, and is spread across their engagement in many different activities.