Chapter 14Time and EnjoymentMeasuring National Happiness

—

Jonathan Gershuny

Moments of time are directly linked in our UK time diaries to respondents’ assessments of their enjoyment of that time, reflecting their instantaneous experience of time. And our enjoyment of time can be expected to feed directly into our feelings of happiness, or wellbeing, which, aggregated up, is in the end perhaps the most important measuring standard we have. There has been a growing interest over the 21st century from national and international policy agencies in the measurement of national happiness, or wellbeing. Aggregate population measures of wellbeing can act as alternatives to the standard economic money-based measures (such as Gross Domestic Product, or its extensions to include unpaid work as in Chapter 6) for assessing the success of societies’ policies. The influential ‘Stiglitz Report’,1 commissioned by the OECD Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, concluded that ‘the time was right to shift emphasis from measuring economic production to measuring people’s wellbeing’.2

We measure diary respondents’ enjoyment of their time from the column we included for this purpose in the 2014–15 UK TUS (column on the far right-hand side of the diary illustrated in Figure 1 of the Introduction).3 The enjoyment of time measured in this way is sometimes referred to as a measure of ‘objective happiness’4 (though this can be confusing given that enjoyment, and its accumulation as a feeling of happiness, is so obviously a subjective phenomenon!).

This method of measuring the instantaneous enjoyment associated with particular episodes of time provides an alternative to more conventional methods of measuring the enjoyment of time. The most straightforward of these is simply to ask the general questionnaire survey-type question: ‘How much do you enjoy … cooking? … shopping? … doing DIY? … going to the gym? … caring for children?’ But do we really know how much we enjoy the different categories of things we do, in the abstract? Perhaps we may be more aware of how much we generally enjoy some of these things, less aware of others. Or do we simply have some sort of general expectation that we will enjoy particular activities? So how do we answer these questions? Do we try recalling and balancing all our past experiences to produce some sort of average estimate? Unlikely – indeed, pretty near impossible. Or do we simply recall the last time we did something? Or again, do we provide some response corresponding to a general principle of self-representation along the lines of ‘I’m the sort of person who enjoys …’?

In fact, since these feelings are in reality attached to specific instances of activity, people are much more likely to respond accurately to a column in a diary asking how much they were enjoying themselves at a specific time.5 So a measure of enjoyment derived by asking diary respondents to report their enjoyment of each 10-minute interval of time, is just about as close as we could hope to get to a valid and reliable measure of instantaneous enjoyment. And these measurements of the instantaneous enjoyment of individual episodes of time (sometimes referred to as ‘experience’ measures) can be aggregated, for individuals or for whole populations, into an overall measure of happiness, or wellbeing.

Enjoyment from the UK 2014–15 time-use diary

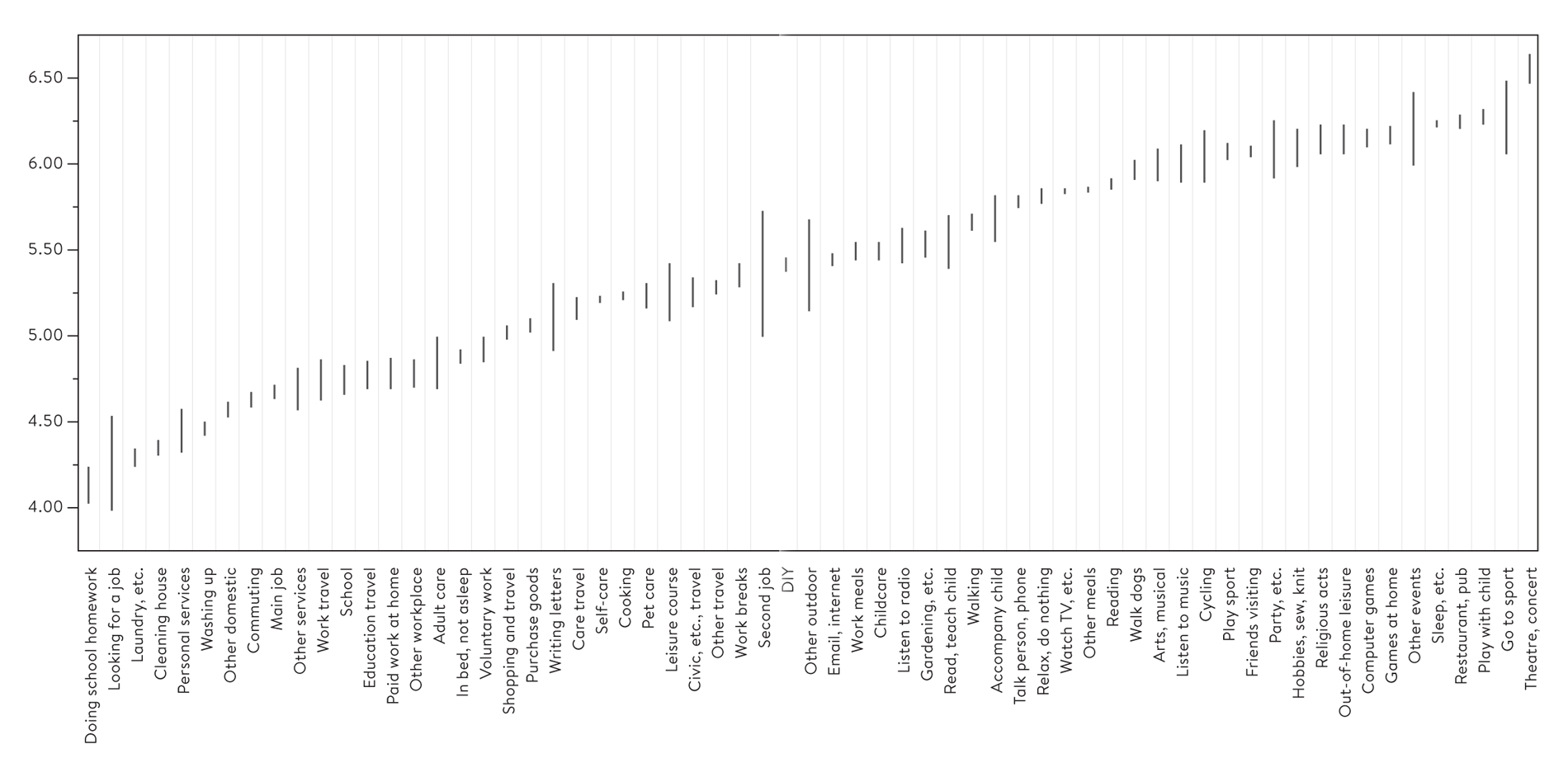

Figure 14.1 shows what the UK population enjoyed doing most (and least) in 2015. It provides a plot of mean daily enjoyment levels from the UK Time Use Survey for 63 different activities (or groups of closely related activities) that together add up to the 24-hour day. The activities are ranked by their mean daily enjoyment level, from the least enjoyable on the left side of the graph, to the most enjoyable on the right-hand side.6 Ninety-five per cent confidence bars for the means are shown (the mean is at the exact midpoint of the confidence bar for each activity).7

There are interesting and easily interpretable differences in the levels of enjoyment of time spent in different activities. The activities receiving the lowest ratings are predictable: doing school homework (the lowest-rated activity, with a mean of 4.14); job search; and various housework activities. The most enjoyed activities, with mean scores above 6.25, also predictably involve outdoor leisure activities such as eating out, going to sports events or cultural performances, and playing with children.

As we read along the ranked range of activities from left to right (least to most enjoyed), we find small clusters of activities with somewhat similar enjoyment levels (main job, school, work and educational travel, for example). As we would hope, these groupings tend to include rather similar sorts of activities. Right at the bottom of the enjoyment scale (at the left-hand side of the figure), we find unpaid work: laundry, house cleaning, and so on. And then, next to the bottom of the enjoyment order, with a mean around 4.75, we find paid work, whether at the workplace or at home (generally and quite significantly preferred to the basic housework activity categories).

Average daily enjoyment levels (95 per cent confidence intervals): sample aged 8 and over, UK (2015)

Moving on, with mean scores ranging from 5.00 to 5.25, we find other sorts of somewhat more pleasant chores, shopping, and care of others, with their associated travel; then self-care (personal toilet) and cooking, all significantly preferred to the various sorts of paid and unpaid work activities located to their left in the graph. Rising towards a mean enjoyment score of 5.50 we have some of the more entertaining aspects of work including workplace breaks and do-it-yourself decoration and construction. Then, between scores of 5.50 and 5.75, we have activities that combine aspects of work and recreation – gardening and accompanying children – as well as listening to the radio. Approaching an enjoyment score of 6.00, we pass through various leisure activities: television, reading, walking dogs, listening to music. Between 6.00 and 6.25 we find playing sports, cycling, social life, parties, hobbies, computer games and religious activity. And finally, with an enjoyment rating just under 6.25, we have sleep – exceeded in enjoyment only by out-of-home eating and drinking, playing with children, and going to sporting events. Absolutely top-ranked is going to cinemas, theatres and concerts, with a mean score of 6.60.

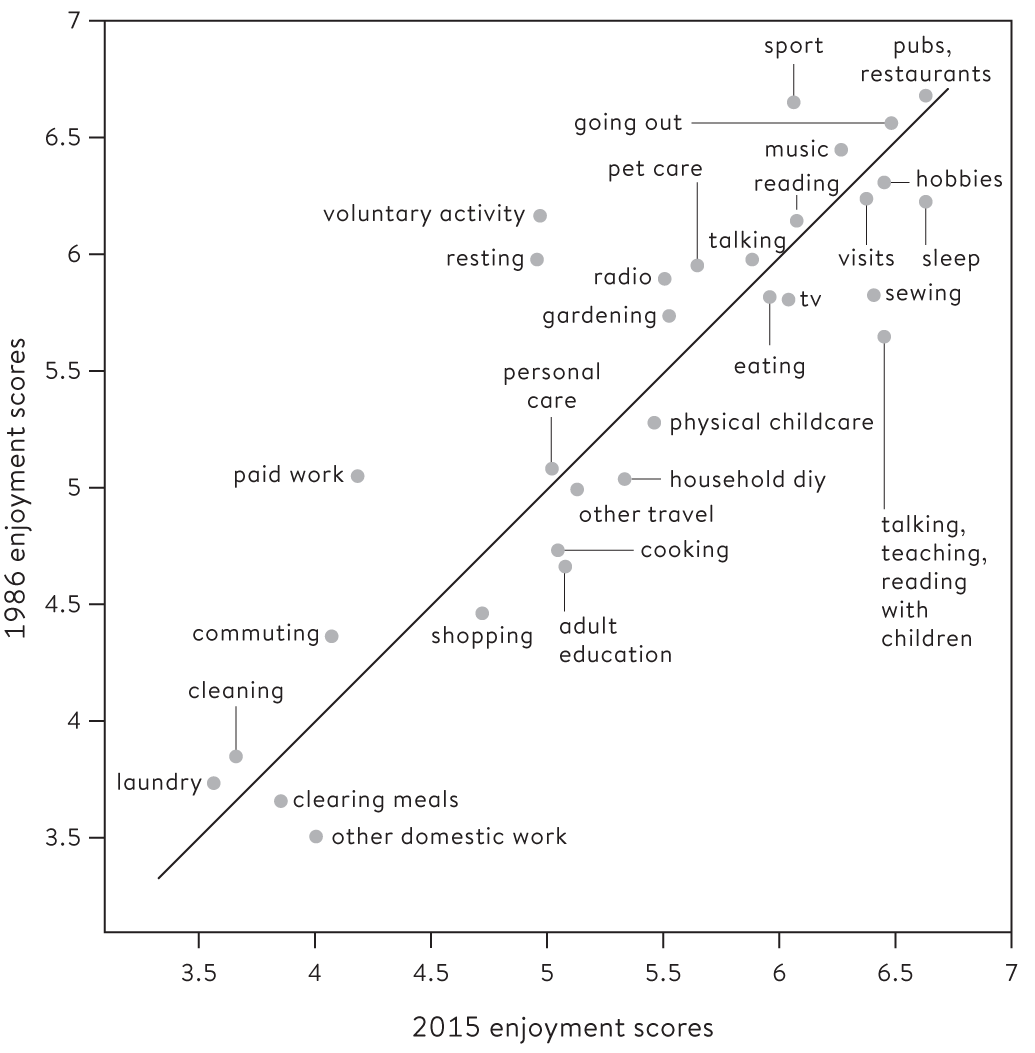

The enjoyment ranking of the various activities emerging from the diary data is, in short, entirely clear and plausible. It is also historically quite stable. In 1986 a Unilever market research survey in the UK used a similar technique to collect diary enjoyment measures.8 Despite being nearly 30 years older, and based on a more limited sample (adults in couples), the results that emerged from this survey were really very similar. Figure 14.2 plots the mean enjoyment scores for each activity in the two studies against each other, re-categorizing the 2015 results to correspond to the 30 categories of activity used in the 1986 study. The linear correlation of .886 between the 30 pairs of mean enjoyment levels shows that the two sets of scores are surprisingly close – about three-quarters (0.8862) of the variation in the 2015 scores is explained by the 1986 scores (or vice versa). This shows that the ranking of levels of enjoyment is broadly consistent throughout the period between the two surveys, with laundry and other housework right at the bottom, and going out to the cinema or concerts, pubs and restaurants and sleep at the top.

Those activities that lie above the diagonal line shown in Figure 14.2 are those that were more enjoyed in 1986 than in 2015. Those below the line were more enjoyed in 2014–15 than in 1986. The most evident changes in enjoyment levels between the surveys are reasonably easily explicable by what we know has changed in the UK during the 30 years between the surveys. Paid-work time, for example, was much more highly rated in 1986 than today: we suspect this is a reflection of the fact that jobs have since become more precarious, pressured and stressful. Voluntary activity, similarly much more highly rated in the earlier survey, may be affected by the deterioration in the level of welfare provision by the state, and the resulting extra burden on people providing care for others on an unpaid, informal or voluntary basis. The enjoyment of rest time may perhaps have been affected by the growth in use of new ICT technologies eating into time that previously was spent in a more relaxing way (see Chapter 13). On the other hand, there are a cluster of activity categories that were more enjoyed in the 2015 survey. In particular, developmental childcare activities such as playing with children are, simply, more highly regarded now than they were previously. This change is clearly reflected in the increase of the amount of time devoted to such activities by parents over this 30-year period (Chapter 5). Sewing also stands out as an activity that is much more enjoyed today than 30 years ago! While the prevalence of sewing has decreased substantially over the 30-year period, its enjoyment rating has markedly increased. This reflects its progressive change in status, over this period, from a domestic responsibility to an elective hobby. Similar arguments may be made in respect of cooking, DIY and shopping – all activities with mid-level enjoyment rankings – which, with the growth of outsourcing and online opportunities as substitutions, have become more elective and enjoyable activities for those who spend time doing them.

Comparing the enjoyment of activities in the UK in 1986 and 2015: men and women aged 16–65

Who enjoys doing what?

Time-diary recording of the enjoyment of activities yields consistent and plausible results at the overall level. However, we might expect these enjoyment rankings to vary according to socio-economic and demographic variables such as by gender, educational level and employment status. And indeed, there are some systematic differences in the extent to which different sorts of people enjoy different activities. But these socio-economic and demographic differences seem to have hardly any systematic effect on the ranking of the preferences for these activities. For example, there is an almost constant relationship between educational level and the enjoyment of seven major groups of activities9: in almost all cases, the higher the educational level, the lower the mean enjoyment level. The one exception is in the case of sleep: those with the lowest level of education report lower levels of enjoyment of sleep than do those with higher educational levels. This may be related to the stress and depression known to be associated with living in a ‘just coping’ financial situation. But in the other six major activity groups, the inverse relationship between educational level and enjoyment holds. Of course, we can’t know from this data whether the better educated actually enjoy their activities less than others, or whether they simply express their enjoyment more moderately. But indubitably they do, on average, report lower levels of enjoyment.

Cross-classifying this data by gender, age or employment status makes essentially no difference to the ranking by education, with only a few exceptions. In particular, employed women with no educational qualifications enjoy both the ‘paid work’ and ‘shopping’ groups of activities less than women with some educational qualifications. This may reflect on the one hand the tedious and precarious nature of women’s unskilled paid work, and on the other the stress of shopping with little money to spend.

A second regularity also emerges from this cross-classification. Activity group by activity group through these educational and demographic breakdowns, women generally claim higher mean enjoyment levels than do men. We see five exceptions to this (out of 21 groups), all involving the educationally least-well qualified. Apparently, women with no educational qualifications enjoy many activities less than equivalent men, probably for similar reasons as those we discussed above relating to the stress of precarious employment combined with low income.

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that there is a strong consistency in the levels of enjoyableness of the various different activities of the day. At this point in UK history, it seems that this ranking, as set out in Figure 14.2, has, as Daniel Kahneman suggested,10 something close to the status of an objective social fact.

Enjoying the whole day: overall mean daily enjoyment

We have shown that there are remarkably stable assessments of the enjoyment rankings of activities both over time and between socio-demographic groups. The next question is, how much do people enjoy their time overall? We can assume that people try to maximize as far as possible the most enjoyable ways of spending their time, but we also know that there are constraints (imposed by the need to do various forms of work, for example).

The next step is to put the various activities of the day together to consider overall mean enjoyment levels calculated over the whole day’s activities. Whole-day mean enjoyment scores are calculated as the average minutes of time devoted to each group of activities multiplied by their level of enjoyability, divided by the total of minutes in the day. Some economists11 have argued that these estimates of ‘national utility’ may provide a radical alternative to measures based on national income such as GDP and GNP. They suggested that ‘process benefits’ – their term for the whole-day mean enjoyment measures12 – provide important information about the population’s wellbeing that is independent of money income measures.

Our method of calculating these process benefits as the product of total time spent in each of an exhaustive set of activities and their reported enjoyment values tells us something entirely different to what we get from income-based calculations. It corresponds quite closely, in fact, to John Stuart Mill’s original idea of ‘utility’: in this case, each member of the population individually decides on the value, to her or him, of each sort of activity.13

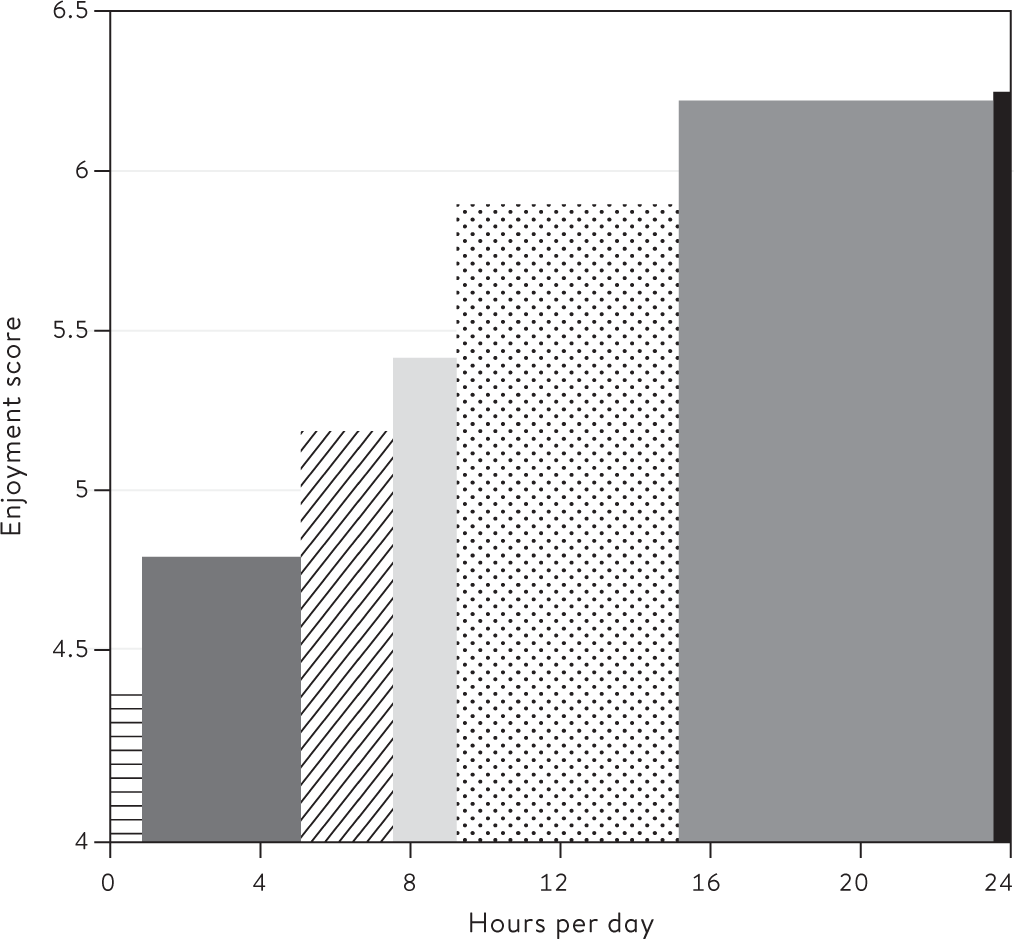

Returning to the concept of the aggregated Great Day described in Chapter 2, Figure 14.3, a base-proportional histogram, shows the make-up, for the adult UK population in 2015, of the overall mean daily enjoyment (or, in the terms above, the overall population process benefit) of the UK population’s Great Day. The vertical axis shows enjoyment scores, while the horizontal axis shows the amount of time (in hours per day) spent in the seven different groups of activities, which are ranked from left to right, as previously, according to their mean daily enjoyment ratings. Bar 6, for example, showing sleep, is both rated highly in terms of enjoyment (scoring between 6 and 6.5), and also takes up quite a large chunk of the day across the population (over 8 hours). Putting these two together, we can see that a lot of enjoyment over the Great Day derives from time spent asleep!

Figure 14.3 Average daily enjoyment of time: men and women aged 15 and over, UK (2015)

Doing homework, looking for job, laundry etc., cleaning house, personal services, washing up

Doing homework, looking for job, laundry etc., cleaning house, personal services, washing up

Other domestic work, commuting, main job, other services, work travel, school etc., education travel, paid work at home, paid work at workplace, adult care, in bed but not asleep, voluntary work

Other domestic work, commuting, main job, other services, work travel, school etc., education travel, paid work at home, paid work at workplace, adult care, in bed but not asleep, voluntary work

Shopping travel, shopping, leisure courses, writing letters, travel to care for others, self-care, cooking and preparing, pet care

Shopping travel, shopping, leisure courses, writing letters, travel to care for others, self-care, cooking and preparing, pet care

Travel for civic and communal duties, other travel, unspecified indoor activities, work breaks, second job, DIY, other outdoor activities, e-mail, internet, work meals, childcare, listening to radio, gardening etc., reading to or teaching child, walking, accompanying child

Travel for civic and communal duties, other travel, unspecified indoor activities, work breaks, second job, DIY, other outdoor activities, e-mail, internet, work meals, childcare, listening to radio, gardening etc., reading to or teaching child, walking, accompanying child

Talk in person or phone, relax, do nothing, watch TV etc., meals at home, reading, walking dogs, arts and music, listen to music, cycling, playing sport, visit friends, party, celebration, hobbies, sewing knitting crafts, religious activity, unspecified out-of-home leisure

Talk in person or phone, relax, do nothing, watch TV etc., meals at home, reading, walking dogs, arts and music, listen to music, cycling, playing sport, visit friends, party, celebration, hobbies, sewing knitting crafts, religious activity, unspecified out-of-home leisure

Sleep

Sleep

Go to restaurant pub or bar, play with child

Go to restaurant pub or bar, play with child

Bars 5 and 7 (the ‘relaxation’ and ‘going out’ activity groups) show the overall enjoyment derived by the population from that part of the Great Day described in monetary terms by the conventional measure of National Product. Extended National Product, on the other hand, places a money value on pretty much the whole of Groups 5, 614 and 7. In the conventional economic view, Extended National Income, the actual and imputed wages and profits of the society, balances this Extended National Product. However, when we consider mean daily enjoyment we can see that the areas enclosed by bars 5, 6 and 7 (broadly, the process benefits of consumption, including sleep) by far exceed those enclosed by bars 1 to 4 (broadly, the enjoyment of work). The final section of this concluding chapter discusses the implications of this evident mismatch between national utility measured as monetary value (through the National Product) and national utility measured as enjoyment.

National income and national happiness: are they the same?

So what can this measure of overall daily enjoyment tell us in terms of ‘national happiness’? The University of Michigan researchers who started this discussion more than 30 years ago referred to ‘the problem’ of the joint dependence of wellbeing on both money income and enjoyment. An example would be a retired person, living on a state pension, who has the time to spend in the most enjoyable activities (the ‘going out’ activities), but not necessarily the income to do so.

The beauty of time-use data here is that we can utilize them, over the same 24 hours, to produce exactly matching measures of both money income and the process benefits derived from the enjoyment of time. The Extended National Income measure is arrived at by multiplying the diary sample’s work time, paid or unpaid, by the appropriate wage rates (and adding the return on the capital used in production). The part of the 24 hours that is not work is defined as consumption time. If we multiply each consumption event within this 24 hours by an appropriate price (or, for the final commodities produced from unpaid work, the ‘shadow price’), and add the savings that contribute to the capital stock, we arrive at an Extended National Product. The central idea of National Accounts is that the total of National Income is identical to the total of National Product. The two parts of the day represent the same money value from two different perspectives, respectively the money value as produced by the producer and as consumed by the consumer. The 24 hours of the diary day can thereby be used to produce two identical estimates of money income – the time spent producing and the time spent consuming.

However, at the same time, exactly the same 24 hours of the diary day can produce matching estimates of process benefits, equivalent to overall mean daily enjoyment for the population. Just as in the money income/output case, every minute of the day has an enjoyment value (as well as a monetary value). But in the case of enjoyment the value relates to the direct subjective experience of each respondent, as opposed to the collective wage or price values imposed on the various sorts of work and non-work time by the market or some other remote mechanism. This allows us to consider the subjective experience of work and non-work time in parallel, using the same units. Consider Figure 14.3. We can use the overall mean daily enjoyment calculations to understand what the effect of particular policy changes might be on national wellbeing, or ‘happiness’. The bulk of the society’s paid and unpaid work is located in bars 1–4, below the 8.5-hour point on the horizontal axis. Work time is enjoyed less, sometimes much less, than the overall mean daily enjoyment level, while consumption time is enjoyed more. What if, for example, future policy changes were to reduce public support for paid elder care and other social provisions, passing the burden of these relatively non-enjoyable activities to unpaid voluntary agencies and private households. Social care activities, irrespective of whether they are paid or unpaid, are not subject to much technical change, so they will exhibit little productivity growth, but at the same time, as the population ages, these policy changes would mean that more unpaid work emerges in this sector. Meanwhile, assume that a proportion of the paid work associated with social care has been transferred to other sectors of the economy which have higher apparent productivity growth. Under these conditions GNP might show a healthy rising trend – but process benefits, the population’s overall mean level of enjoyment of daily life, would simultaneously decline.

This is not to say that we necessarily expect this particular pattern of change to happen (though it does correspond to a central plank of the UK Conservative Party’s austerity public policy just a few years ago). It is possible to envisage various scenarios that might produce quite different patterns of association between GNP and national happiness. But the conclusion that emerges is that if we take GNP alone as our guide to economic policy we might inadvertently damage national happiness (as measured through overall daily enjoyment). The joint dependence of national product and national happiness on the same 24-hour statistics provides a straightforward means for a properly integrated account of the evolution of these two important dimensions of public policy outcome, allowing us to postulate which courses of policy action might produce gains in both national product and happiness simultaneously.