CHAPTER TEN

Improbably, it was only six thirty at this point. Through the powerful, time-bending power of Sugar Sugars, I felt that I had lived through decades with Quintrell and Nathan and Tyler and Masako, or at least several hours, but not only was the night young, it was still day.

“What do you mean she’s a private detective?” asked Tyler.

“She’s a private detective,” said Masako. “I think she’s at Cahaba to investigate something but she won’t tell me what.” Basically Masako was spilling the beans on absolutely everything I had hoped to keep secret. There would be no beans left after this. I would have an empty can of beans; there wouldn’t even be any beany residue.

Time to make the most of the situation.

“I am not a private detective,” I said. “I’m just taking classes in that direction, on the side. And I’m not there at DE to investigate anything. I’m just temping.”

“Dahlia’s very good, though,” said Nathan. “Show Tyler where you got shot in the arm!”

“Maybe you should investigate,” said Tyler. “Quintrell got arrested.”

“I can’t imagine that’s right,” said Masako. “He seemed very unconcerned about it. He was mostly going on about Gloria.”

“There’s no way he’s murdered anyone,” said Tyler. “It’s completely impossible.”

This was probably true. What possible reason would Quintrell have had for bumping Cynthia off? He had described her as being a pleasant WYSIWYG. That’s just not murder talk.

Earlier, I had planned to attend Cynthia’s old knitting circle incognito and learn what I could about her. That plan was jettisoned when it seemed like it would be more fun to drink. However, now that Quintrell King, Obvious Victim of Fate, had been arrested, it seemed like I should reconstitute it, except that I was:

1. Drunk.

2. In a party of three.

3. Drunk.

I put drunk twice, as it was the principal problem with this plan, and also because I got confused while making this list.

“You guys should go home,” I said. “I’ve got some work to do.”

“I think we should get a cab,” said Tyler. “I’m not really up for driving.”

“I have to leave,” said Nathan. “As plant and microbial sciences goes, so goes my country.”

“What kind of work?” asked Masako.

“Well,” I said. “I suppose you might be inclined to call it detective work. And it’s fine, Nathan. I got this.”

“I don’t know,” said Nathan. “You’ve been attacked in some pretty unusual places. You got concussed in a family restroom.”

“Family restrooms are hotbeds of sin,” I said.

“We’re coming with you,” said Masako.

“What?” said Tyler.

“We’ll help,” said Masako. “We’ll keep guard.”

“What are you going to do?” asked Tyler. “Specifically.”

I relayed my plan to the gang, who each took it differently. Tyler, although impressed that I had sussed out this bit of Cynthia’s schedule, seemed to regard my sleuthing as a profound waste of time. (I guess his hidden depths speech was just drunk talk.) Masako, on the other hand, regarded my little plan as a work of Holmesian genius, and instantly confirmed they would come along. I am not sure which of these reactions surprised or concerned me more.

Nathan admitted: “It does seem like you’d be pretty safe at a knitting group at a church.”

“I think so,” I said.

“Vampires can’t even get in,” said Nathan.

“How long are you going to be playing host to your grad student?” I asked.

“Three days,” groaned Nathan. But then he smiled his own apex predator smile at me. “Although I get time off for good behavior.”

As a rule, I don’t go to church a lot. I don’t have a particularly antagonistic relationship with churches, as my friend Steven does, who thinks he will burst into flames the moment he walks through the door. I just don’t get around to it very much. Church is something my parents do, and even then not very well. We Mosses are not a naturally religious people.

But I like the idea, at least in the abstract. Nothing wrong with church; it’s just that most Sunday mornings I tend to be hungover.

Now, however, as I stumbled into the First Presbyterian Church of St. Charles, Steven’s church/flame scenario seemed not entirely out of the question. Walking into the basement of a church while somewhat drunk, it was hard not to feel a little bit pagan. And not in a charming roguish way. In a sad drunk way.

On the plus side, I was at least walking into the basement, which was carpeted in this horrible orange stuff that really looked like it belonged in a dorm room and not the actual chapel. This was essentially a rumpus room, a natural place to be a little tipsy. The problem was that it was God’s rumpus room. Sorry about that, God. The evening had taken a few hard turns.

Hopefully God would understand this particular transgression, because I really was aiming to do good, and he had god-sight, after all. The bigger issue I faced was with the knitting ladies, who did not have god-sight and were likely inclined toward Old Testament justice.

I had gotten there a hair on the early side, and there were three ladies so far. Their total ages probably summed up to be more than two hundred. The first of them, Linda, had improbably long stringy hair. She was tall and thin and wispy and seemed a bit like a flower child that had been left out in the sun too long. Next to her was Margery, the very picture of venereal brawn. She was stout and had short, wiry black-to-gray hair. In between the two of them was Joanne, who was exceptionally well dressed, with a fancy ruby brooch and gold-rimmed glasses. Joanne was obviously the ringleader of this operation.

“Are you in the right place, dear?” said Joanne.

Joanne had a faint Southern accent—but an aristocratic one. She looked like old money and new clothes, which was not a bad combination.

“I’m here for Presbyterian knitting,” I said. I had bummed a breath mint off the Uber I had taken on the way over here, and I felt that this was pretty helpful for covering the smell of Sugar Sugar on my breath. I mean, nobody would hand me the keys to their car if they got close enough, but I didn’t think I was wafting off an aura of drunken woman.

“Can I get you some water?” asked Joanne, who was glaring at me. She gave good glare. Professional-level glare.

“Are you, by any chance, a retired teacher?” I asked her.

Margery, of the wire hair, slapped her knee with delight.

“I’m not a retired teacher,” said Joanne. “I was an organizer for the teachers union.”

“Don’t be pedantic,” said Margery. “You taught for many years before that. Now, how could you tell?”

Some quick judgments about Joanne: She was pedantic, and was not about to make any admissions that were going to give me a gold star. She probably didn’t realize this, but she would have fit in great on Reddit.

“It was just a lucky guess,” I said. “Although, I’m a private detective. Lucky guesses are sort of my thing.”

I had planned on arriving here under a cover story of some kind, but suddenly playing a couple of my cards here seemed like a good idea. It gave me a good pretext for asking questions. And an element of danger. And it also explained why I might smell like booze and breath mints.

“I’m impressed,” said Linda, also delighted.

“Where are your knitting needles?” asked Joanne, who was just as clearly not impressed.

“Do you need needles?” I asked, posing perhaps the dumbest question that had ever formed on my lips, which, if you’ve read my previous adventures, was saying something.

“Yes,” said Joanne. “You need needles.”

“I’ve got some extra,” said Margery.

“Did you bring any yarn?” asked Joanne, who had a face that was capable of sending you to the principal’s office without a word.

“I left my yarn at home,” I said.

“Then maybe you should go back and get it,” said Joanne.

I sat down, which was pushy, arguably, but I could use the rest. The gals were seated around a dinged-up wooden folding table, which looked to be part and parcel with the basement, although the chairs were nice.

“I suppose,” I said, “to be perfectly honest, I mostly came to ask you a few questions.”

“Knitting questions?” asked Linda, her voice flooding with optimism.

“Questions about a fellow knitter of yours—Cynthia Shaffer?”

“You’re here to ask us about Cynthia?” asked Joanne, who was in more disbelief at that revelation than at my forgotten yarn.

“Yes, actually.”

“How do we know you’re really a detective?” asked Joanne.

“She could be one of those Internet identity thieves,” said Linda.

“I suppose you’ll just have to take it on faith,” I said. “I’m a private detective. I’m not with the police. But I’m definitely not going to ask identity-thieving questions.”

“What would be an identity-thieving question?” asked Margery, quite contemplatively, as though she were taking up the idea herself.

“Social security number, birthday, all those things they ask you when you want to reset a password.”

“Where did you go to elementary school?” said Linda.

“Right.”

“What’s the name of the first boy you ever kissed?” said Linda.

“Yup,” I said. “And it was Leland.”

“What possible reason could you be investigating Cynthia for?” asked Joanne. “She hasn’t done anything.”

In the moment, I observed that the topic of Cynthia Shaffer had affected the three ladies in markedly different ways. Linda had brightened, and I got the impression she’d have been perfectly happy to talk about Cynthia ad infinitum. Joanne had darkened, which was impressive given the skeptical point she had started from, and Margery just seemed like she was along for the ride.

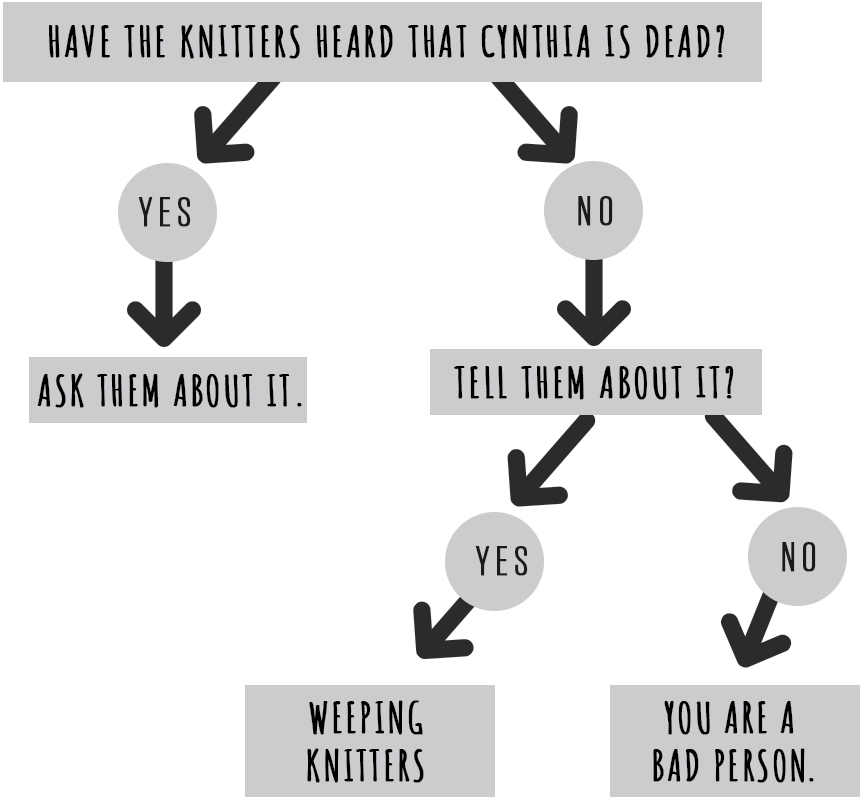

“I didn’t say I was investigating Cynthia,” I said. And suddenly I was at a crux point. For once, I hadn’t hit upon it blindly; I had known this moment would come. I had even made a little mental flowchart about it on the ride over here.

I didn’t love this flowchart. It wasn’t my best work, as I’m sure there should be other options, nor was I fond of its moral implications. But, it was decision time. I did not want to deal with weeping knitters, and so I decided not to bring up Cynthia’s passing.

“I’m not investigating Cynthia,” I said. “I’m investigating the company that she worked for.”

“Worked for?” said Joanne. “She doesn’t work there anymore?”

“She was fired.”

Joanne looked floored by this somehow, although the other ladies didn’t even miss a purl.

“I don’t think it’s appropriate,” said Joanne, “for us to be talking about her behind her back.”

“She could walk in on us,” said Linda. “What would we say?”

“I would love if she walked in on us,” I told Linda, in what was certainly an epic lie. “My questions aren’t anything secret. I’d like to talk to her too. I haven’t been able to reach her.”

“Me neither,” said Margery. “But I’m sure she’ll be here. She’s often a little late.”

“I don’t like this,” said Joanne.

“Anyway,” said Linda. “She hated that place she worked for. What was it called? Caldera?”

“Cahaba,” said Joanne. “It’s named for a river in Alabama.”

“It sounded like a nightmare. Cynthia would tell us all about it every week. I always figured she was making some of it up, you know, for the sake of a good story, but, goodness, now there’s a detective here,” said Linda.

Joanne, for her part, was shooting off daggers and also knitting in a loud and dangerous-sounding manner, as though she intended her needles to be a sort of threat. But Linda was one of those people who possessed powerful rockets of optimism, such that things like threatening scowls and needles were rendered powerless.

“What kinds of things went on?” I asked. “I’d heard the work schedule was crushing.”

“For everyone else,” said Linda. “Cynthia didn’t stay any longer than her eight hours.”

“She’d stay nine hours some days,” Joanne said. “And she’d bake for the kids that worked there. She just felt terrible for them. Being run ragged by some corporate monster.”

“Did you know,” asked Linda, “they had a special room for crying? Isn’t that amazing? It was called ‘The Crying Room.’ People would just go in there and cry, you know, privately.”

“They had to add a second room,” said Margery. “There was ‘Crying Room A’ and ‘Crying Room B.’”

“Did she mention anyone who particularly hated the company?” I asked. “Did Cynthia hate the company?”

“These are questions for Cynthia,” said Joanne.

“I wouldn’t say Cynthia hates the company,” said Linda. “She just thought it was very badly run. The only thing I’ve ever heard of Cynthia hating is Kanye West.”

“Who’s that?” asked Margery.

“Some rap man,” said Linda.

“Why is she even familiar with him?” asked Margery, and I was grateful to Kanye for taking some of the heat off me.

“Her granddaughter is a big fan,” said Joanne. “She keeps making Cynthia listen to his songs so she will appreciate his genius.”

“Oh,” said Linda, “that sounds terrible,” and I was a little with her on this point, although I did not have time to interrogate these ladies over Kanye’s career.

“I thought Cynthia was single,” I asked. “She has a granddaughter?”

“She has three,” said Margery.

“Her husband died ages ago,” said Linda. “In the eighties. Drunk driver.”

“I just don’t think we should be spilling Cynthia’s personal details like this,” said Joanne.

I asked another question to head this off.

“Did Cynthia mention anyone else from Cahaba who hated the company—maybe about not being able to spend enough time with their spouse?”

“Maybe Joanne is right, Linda,” said Margery. “This is getting a little personal. We should wait for Cynthia to show up.”

But there was no stopping Linda.

“Everyone there hated it,” said Linda. “The boss lady, the artist, black guy, beard guy. Everyone hated it, except for the rich one—what was his name? Lawrence?”

“He was happy. What are you looking for, exactly?”

“Linda,” said Joanne. “Let’s not answer all of these questions.”

“Did you know that the boss lady and the artist were having an affair?”

“Linda,” said Joanne again.

“How about that the boss lady was pregnant—or that’s what Cynthia said—”

“What?”

“Linda,” said Joanne. “Let’s wait for Cynthia.”

“She found a used pregnancy kit in the trash. Two blue stripes.”

“Linda,” said Joanne, with remarkable patience at this point.

“I assume it was the artist. Oh, did anyone tell you about his violent drawings?”

“Linda,” came a voice, which I initially assumed was from Joanne again, even though it had come from behind me. I suppose I had assumed that Joanne was employing ventriloquism to make her case, since normal speech wasn’t working. But I turned, and found, quite to my shock, that it wasn’t Joanne.

“Hey look,” said Linda. “Cynthia’s here! Margery was just talking about you.”

I’ll be damned.