CHAPTER ELEVEN

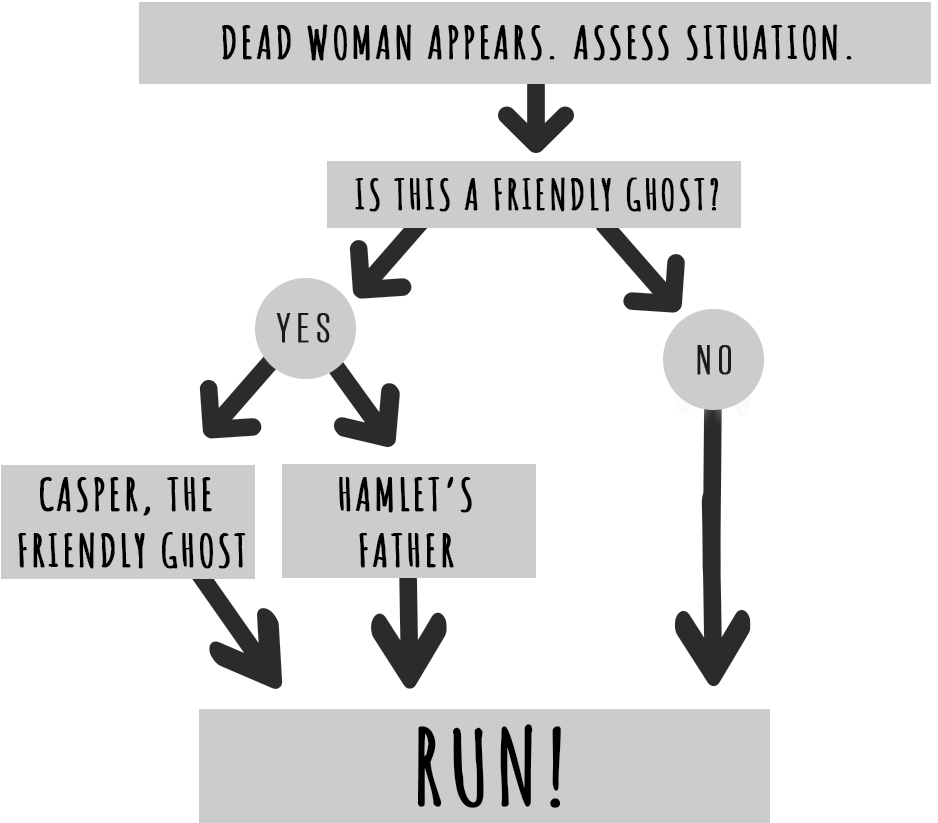

Cynthia Shaffer, dead woman, walking into the room and giving me guff was not a scenario that I had included in my flowcharts. If I had, it would look like this:

This was roughly my mental state. I stood up and was rapidly moving into a sprinting stance. Dead women don’t show up while you are investigating them. I was not ready to cross the line into urban fantasy, and if I was, I wanted to do it with a shirtless guy who could turn into a hawk, not a dead old woman with a calico knitting bag.

Anyway, I was a freaked-out mess, which was a marked contrast to everyone else there, who were saying things like:

“Hi, Cynthia!” and “Sit yourself down.”

“Why are you standing?” asked Linda.

The answer to this question was that I was giving even odds that Cynthia Shaffer was a dead apparition who meant me harm. But I did not want to state that aloud because it (1) sounds crazy and (2) might give the apparition some ideas. But I sat down.

“This detective,” said Joanne, who was still gruff, but less so, “has been asking questions about Cahaba.”

“A detective,” said Cynthia. “That’s exciting. Of course, a detective’s not going to help that place. They should send an exorcist.”

Then Cynthia laughed. It wasn’t a booming, see-the-face-behind-the-skull laugh, although I may have processed it that way at the time. With the power of retrospect, it was just a plain old guffaw.

I was beginning to pull my wits about me. I’ve discovered enough corpses now that I just don’t get as upset as I once did. I’m not a superstitious person, but when you encounter a dead woman at a knitting group—a live dead woman—it tends to pull at your rationalism.

“You’re”—I was going to say alive, but I decided that this was the wrong word choice—“looking well.” Which meant the same thing but was less suspicious.

And the thing was, Cynthia was looking well. She exuded energy and relaxation. She also smelled like lemongrass and lavender. And her hair was exceptionally coifed. She did not look at all like a dead woman. She looked like she could be above an infographic in AARP magazine about living your best life. She seemed exceptionally alive. “Jonathan Strange back from the dead” alive. She looked like she could go jogging.

“Why thanks,” said Cynthia. “I knew I liked you when I walked in.”

“What’s that smell?” said Margery.

“Some fancy shampoo,” said Cynthia. “After they fired me, I took a spa day.”

“Well, that seems decadent,” said Joanne.

“I had a coupon,” said Cynthia. “Valerie got it for me for my birthday.”

“Was it the place out on Hamilton?” asked Linda. “That place is the best.”

“No,” said Cynthia. “I don’t know that one. What’s it called?”

“Something about Wax. WaxWorks? House of Wax?”

“House of Wax is a horror movie,” said Cynthia.

“Excuse me,” I said. “I need to run to the bathroom.”

“Don’t you have questions for Cynthia?” asked Linda.

I had plenty of questions for Cynthia. Some of which now included: How are you alive? Can you tell me what the afterlife is like? But I did not venture into these philosophical waters with the knitters. I found the women’s bathroom and I hid there.

As I calmed down, I put together some salient points. I had not closely studied the corpse on the ground. Corpse woman was facedown, and I only got her in profile. While this person certainly looked like Cynthia Shaffer—the same age, the same body type—maybe this was my mind playing tricks on me. Surely they were different people. They had to be.

I decided to call Detective Anson Shuler, which I felt was entirely reasonable given the circumstances.

“Dahlia?” he said. “Are we still on for roller-skating tomorrow evening?”

I had unwisely agreed to—nay, suggested this plan—a few days ago after being hit on the head. But there was no backing out of it now.

“I found a body,” I said.

“What?” said Shuler. “Another dead body? What are you, Harper Connelly?”

“No,” I said. “This is a living person. She’s just walking around, talking about spa days.”

“You found a living person,” said Shuler.

“Talking about spa days,” I added. “Like it’s no big deal.”

“Are spa days a big deal?” asked Shuler. “I’ve never been to one. I was reading this article in the New York Times about how men are starting to use them, but I’d feel weird about it. Why, did you want to go?”

Taking a spa day with Shuler would be more fun than roller-skating, I imagined, but this was not the point.

“She is supposed to be dead,” I said. “I found a woman who is supposed to be dead.”

“What do you mean?”

“She is supposed to be dead.”

“And she’s—”

“Hmm,” said Shuler. It was a noncommittal hmm. It was a hmm that possibly meant: I think Dahlia is out of her mind. And so I updated Shuler on my adventure thus far, carefully leaving out that I entered into this shitshow because I was doing work for Emily Swenson. When I finished, Shuler asked me where I was, and then told me that he would be there in a half hour.

My next task was to leave the restroom and interrogate the obviously not-dead dead woman. I had come to my senses now and regarded Cynthia Shaffer as I would any living woman who had somehow elaborately faked her death. Which is to say: wtf. But I wasn’t worried about her killing me with her wraith touch, so that was good.

Mostly because I wanted to forestall this interview, I called Emily, who also needed some updating.

“Dahlia,” said Emily. “Two phone calls in one day. Any progress on that stolen code?”

“No,” I said. “None whatsoever. But I thought I’d keep you posted on the lay of the land.”

“I like knowing the lay of the land,” said Emily.

“Quintrell King, a programmer for Cahaba, was arrested about an hour ago for Cynthia Shaffer’s murder.”

“Yes,” said Emily. “I’d heard that. Why, do you know anything about it?”

“I know that he didn’t do it,” I said.

“How do you know that?” asked Emily.

“Because Cynthia Shaffer is in the next room, talking about shampoo.”

Emily, for once, was quiet.

“Cynthia Shaffer is alive?”

“Not only is she alive,” I said, “she’s knitting.”

“And that’s the lay of the land,” said Emily.

“Yes,” I told her. “The lay of the land is a Boschian hellscape.”

“Thanks for letting me know,” said Emily. “But don’t get tangled up in this. Just focus on the whistle-blower letter and the code. We need that code.”

I did have to admire Emily’s single-mindedness. A woman getting murdered, a man getting arrested, and the murdered woman apparently returning from the underworld to cash in a coupon at the House of Wax was not enough to bend her from her task. I did not possess this level of focus, but I told her I’d try.

I then got off the phone and returned to the room.

Even coming to my senses, as I now was, I found that it wasn’t any easier being in the room a second time. The banality of the knitters’ discussions mixed with the improbable element of a dead woman sitting around, talking about missed purls, proved to be a bizarre and distracting cocktail. What was happening?

“It’s very strange,” said Joanne, “that you came here on this big cloud of puffery about needing to ask questions to Cynthia, and then when she arrives, you disappear.”

Had I arrived on a cloud of puffery? I felt cloudy, but I was pretty sure I had kept the puffery to a minimum.

“I had some intestinal experiences in the bathroom, Joanne. It’s not like I ran for the border.”

Joanne looked exceptionally irked by my tart response, but it buoyed Linda, who slid over some yarn to me. Still no needles, but there was a pile of yarn. I had no idea what to do with it. Literally everything I know about knitting is from Yoshi’s Woolly World, a game in which a dinosaur eats yarn and spits out sweaters. It was not a great point of reference.

“It’s fine,” said Cynthia. “It’s not like I’m leaving anytime soon.”

I picked up the yarn, which was tangled, and tried to fix it, both because this looked like a productive thing to do and because it was a metaphor. As I wound up the yarn, I put together what I knew.

1. I had found someone in that storeroom.

Right? Somebody was dead. I didn’t hallucinate it.

2. The dead person was not Cynthia.

Because she was here, obviously.

3. The dead person was Cynthia shaped.

Everyone thought it was Cynthia. Yeah, I didn’t really roll over the corpse and take photos of her, but the impression was that this was Cynthia Shaffer. So why was there a dead person shaped like the secretary in the storeroom?

“So anyway,” said Cynthia. “Did you see CSI last Thursday? It was a good one.”

“No,” said Joanne, “we all hate that show. You’re the only person here who likes to discuss it.”

“I like the show,” said Margery.

And they carried on, apparently untroubled by my rattled yarn skeining. The fact that they were so untroubled by my presence—Joanne was irritated, but no more—led me to another point.

4. Cynthia Shaffer had no idea about the Cynthia Shaffer–shaped dead woman, or else she wouldn’t be so blasé.

“So,” I said. “Do you have time to answer a few questions about Cahaba?”

“Oh look,” said Margery, “she’s come back to us.”

“Are you on drugs?” asked Linda. “I’m asking without judgment. It’s just—you were miles away for a moment there.”

“It’s just been a long day,” I said.

“You’re really a detective?” asked Cynthia.

“I’m really more of a junior detective,” I said, regretting my choice of words, because it made me sound like I should be operating out of a wooden tree house. “I’m still taking coursework. I guess you could call me sort of a working intern. Although I’m getting paid.”

While this was arguably oversharing, I had found that the more honest I was about being legit but inexperienced, the more people tended to open up to me.

“Why are you looking into Cahaba?” asked Cynthia.

“That’s an interesting question itself,” I told her. “But my client really wouldn’t want me to say.”

“What do you want to know from me?” asked Cynthia.

“Do you want to go somewhere private?” I asked.

“No, I want to knit,” said Cynthia. “These gals know everything about me anyway.”

I found myself thinking of Sydelle Pulaski, a character in The Westing Game who, in working out the mystery of that book, incorrectly thinks the solution involves someone having a twin. As such, she spends much of the book trying to work twins into conversation, such as the Bobbsey Twins or the Minnesota Twins or Twin Jets. I thought of her then, because I suddenly identified with Sydelle’s plight. I certainly wanted to know if, by any chance, Cynthia had an identical twin, but this was a weird question to come out and pose. At least initially, anyway.

I started with:

“Why did Vanetta Jones fire you?”

“It was more of a mutual parting,” said Cynthia.

Anytime anyone tells you that it was a “mutual parting,” you should be skeptical. The term gets thrown around very loosely. (“I didn’t burn down my house; we mutually parted.”) But I decided not to grill Cynthia on this probably precarious point. Flattery would get me farther.

“That’s surprising,” I said. “From what I hear of it, everyone around there loved you to pieces.”

“Oh, not everyone,” said Cynthia.

“Quintrell King adores you, Gary spoke well of you, Tyler thought you were interesting and complicated.”

“Well, well, well,” said Margery, dispelling the fleeting dream that this interview wasn’t going to be interrupted, “interesting and complicated.”

“I’m with you on complicated,” said Linda jovially, “but interesting?”

“That doesn’t sound like something Tyler would say. And he barely knows me.”

“That’s probably why he thought you were interesting,” said Linda.

“Hush, you. No, Vanetta fired me because I was trying to mother her, and she didn’t want a mother. I”—Cynthia was quiet for a moment—“I crossed a line with her that I shouldn’t have crossed. That place was so screwed up, you start to treat the people there like broken dolls—you just want to fix everyone—and I shouldn’t have tried to do that with her.”

“Is this about the pregnancy test?” I asked.

“What?” said Cynthia, quite shocked. “How did you hear about that?”

“I told her,” said Linda.

“What?”

“I tried to stop her,” said Joanne.

“I like having dirt,” said Linda. “Sue me.”

“We both tried to stop her,” said Margery.

“It’s fine,” said Linda.

Cynthia looked rattled for a moment, but then quickly composed herself. “You’re right, it’s probably fine. I just—well—yes, Vanetta was pregnant, is pregnant, I suppose, and I involved myself a little more than I should have.”

“Did Vanetta tell you this?” I asked. “After you found the pregnancy test in her trash?”

“What?” said Cynthia. “I didn’t go through her trash. Who told you that?”

“I told her that,” said Linda.

“That’s not what happened!”

“Maybe not,” said Linda. “But my version of the story is more colorful.”

“So what really happened?” I asked.

“Vanetta took the pregnancy test there at work—”

“Why would you take a pregnancy test at work?” asked Joanne.

“Well, this is Cahaba. No one goes home. They all just live there, and Vanetta especially.”

“Yes, and so she apparently took the test in the bathroom, and when she came out she started crying. Now, I wasn’t born yesterday, and when a woman goes into the bathroom and then comes out crying, I can put two and two together.”

“I cry in the bathroom all the time,” said Linda.

“And you are an exceptional person,” said Cynthia. “I had just gotten that vibe from her before. I could tell that she was worried about something, anyway—personal, because I had learned how Vanetta compartmentalizes her emotions.”

“Which is how?”

“Carefully.”

“And this wasn’t that?”

“No,” said Cynthia. “She was mopey and strange. I asked her if she was pregnant, and then she ran into her office, crying harder.”

“That’s very impertinent of you,” said Joanne disapprovingly.

“Yes, I know,” said Cynthia. “I’m not proud. So then, of course, I couldn’t leave well enough alone, so at lunch I went out and got her a cake, and then I came and asked her all about it.”

“The father is Archie?” I asked.

“I believe so.”

“And she fired you because you found this out?”

“She fired me because I told Archie about it.”

“Oh, Cynthia,” said Joanne, her voice dripping with disappointment.

“I know,” said Cynthia. “Don’t give me that look. You see why I needed this spa day.”

“You didn’t tell us this part,” said Linda.

“That’s because it makes me look bad,” Cynthia said. “Vanetta didn’t want to tell Archie about it until the project was done.”

“Wait, is she keeping the baby?” asked Margery.

“She hadn’t gotten to that. She was going to wait another month and see if it ‘sticks,’ and then maybe tell Archie about it. But that didn’t sit right with me.”

“Archie’s the roguish one, right?” asked Linda.

“I think Archie would be a splendid boyfriend, and an excellent father,” said Cynthia, quite approvingly. But then a cloud of doubt formed on her face. “Although I’m not sure that he’d work out as a husband.”

“Let’s set up him up with Dorothy’s daughter,” said Linda, then added, to me, “We hate Dorothy.”

Everyone else ignored this remark, although Joanne’s knitting needles were doing Wolverine SNIKTs.

“Anyway,” said Cynthia. “I told him, and it was sort of awful, and then he told her, and then Vanetta brought me into her office and told me that I should probably be fired for this. And I agreed with her, and so I quit. I made a huge mess of things. I don’t even think they’re talking to each other now.”

“Oh, they’re talking,” I said, remembering Archie shirtless in her office.

“Are they? That’s good,” said Cynthia.

“All this meddling reminds me of the movie The Parent Trap. Wasn’t that a great flick? Hey, speaking of The Parent Trap, does anyone have a twin?”