OFF THE WALL

Wherever you go in the world, walls serve the same purpose. They support the roof over our head, protect us from the elements and provide shelter and security. Walls are a reassuring and safe protective barrier that we can hide behind and conduct our daily lives in private, away from prying eyes.

Despite this basic function, walls are also infinitely variable. They can be high, low, smooth or rough, thick, thin and every colour conceivable. They can be constructed from brick, stone, glass, metal, concrete, wood and even mud.

Photographically this variety offers enormous creative potential. Whenever I’m in a new location, especially while travelling overseas, I love to spend a few hours wall watching.

This may sound like an odd pastime, but it’s amazing how much walls say about the culture, the climate, the people and the economy of a place. Not only that, they have enormous visual appeal. Walls are full of patterns, textures and colours. Painted murals and graffiti offer further potential for interesting images, and you can shoot them on both a large and small scale because the closer you get, the more abstract the pictures become.

Light and shade

The quality of light plays an important role in determining how walls appear.

On an overcast day, for example, textures are subdued but fine details are clearly defined and colours appear well saturated.

In full sun, walls take on a more abstract quality. White light striking from an acute angle reveals texture and casts shadows from anything mounted on the surface of the wall such as a lamp, window grilles or signs.

In this respect, overhead sunlight can be just as useful as morning or evening light because it glances down onto the vertical face of the wall, casting shadows and highlighting the slightest imperfection in the surface.

Walls also take on a totally different look and feel at night, when they’re bathed in the colourful glow of artificial lighting. Sodium vapour creates a deep yellow cast while fluorescent light turns everything a lurid green.

HAVANA, CUBA

SCARBOROUGH, ENGLAND

ALNWICK, ENGLAND

WHITLEY BAY, ENGLAND

ISLE OF LEWIS, SCOTLAND

You can see from the locations listed above that these images have been gathered from all over the world, simply because wherever I go with a camera I can’t help photographing them. From colourful abstracts and eye-catching details to wonderful textures and regimented patterns, every wall is a work of art once you take the time to look.

CAMERA: HOLGA 120GN, POLAROID SX70, MAMIYA C220, NIKON F5/LENS: 60MM, 116MM, 80MM AND 50MM/FILM: FUJI NPS160, POLAROID TYPE 779, FUJICHROME VELVIA 50

Patterns and texture

Look for interesting patterns in the materials that were used to build the wall, such as the regimentation of brickwork or the contrasts between rusting iron sheeting and rough timber. Observe the faded glory of crumbling stone and peeling paint, or the vibrancy of painted murals.

Windows and doors are of course common features in walls and they can make fascinating subjects in their own right, as demonstrated on page 118. There are infinite designs, styles and colours that vary not only with the location but also the period of the building. In cities that are visited by large numbers of tourists you will even find posters on sale depicting ‘Doors of …’ Though this may seem rather gimmicky, the images are usually very effective and show that the most familiar features can be a source of great pictures.

Something else you’ll find in every town and city is graffiti, from crude slogans daubed with a brush to amazing murals that exhibit great skill and experience. Some see graffiti as a criminal act, others as art, but whatever your view you can’t deny its visual impact, nor its photographic appeal.

ON REFLECTION

Reflections are a common phenomenon in the world around us. We use mirrors every day to check our own reflection, or to keep an eye on the road behind us while driving. We marvel at the mirror-image of a beautiful scene reflected in calm water, and stand back to admire the reflections in our car’s bodywork after polishing it up to a high shine. Reflections are positive and reassuring because they repeat and multiply, echoing light and colour.

Photographically, reflections have enormous creative potential. In the countryside, reflections in water provide foreground interest and add a sense of tranquillity and balance to a composition. In still weather, scenes are reflected in perfect symmetry while the slightest breeze ruffles the surface of the water to create an ever-changing kaleidoscope of abstract patterns and colours. Rock pools left behind on beaches by the retreating tide reflect the sky overhead and look stunning at dawn or dusk when striking colour contrasts are formed.

Head for the big city and you have more options. Modern architecture reflects clouds drifting across the sky, or mirrors other buildings across the street. Puddles pick up reflections of anything nearby, as do parked cars and shop windows. You could spend the whole day shooting reflections in the urban landscape on both a large and small scale and only ever scratch the surface.

EMBLETON BAY, NORTHUMBERLAND, ENGLAND

The creative potential of water and reflections is evident in this abstract dawn shot. There simply wouldn’t have been a photograph if you imagine the scene without the rock pool in the foreground. Though the colours appear out of this world, they are totally natural. The only filter I used was an ND grad to retain the orange glow in the sky.

CAMERA: MAMIYA 7II/LENS: 80MM/FILTER: 0.9ND HARD GRAD/FILM: FUJICHROME VELVIA 50

Fill the frame

Reflections are mesmerizing. They allow us to set free our imagination and dream, just like Alice and her Looking Glass. So, instead of making the reflection part of the picture, make it the whole picture. Use your lenses and your feet to close in and fill the frame so all extraneous information is excluded. Forget about reality. Look at the reflection for what it is – an arrangement of shapes and colour or shapes and tones – and let them take centre stage instead of being a mere prop in a bigger picture. That way the viewer really gets to see the reflection and lose themselves in it.

Leaping back to reality for a moment, there are a few factors to consider when photographing reflections.

One: Always focus on the reflection itself rather than the reflective surface, otherwise you may find that your reflection isn’t quite sharp and its impact will be diluted.

Two: The angle you shoot from can make a big difference to how the reflection appears. If you’re standing next to a puddle or pool the reflection you see will be totally different if you crouch down. Always experiment with angles before shooting.

Three: If you want to capture clear reflections in water you need calm weather. Early morning is a good bet. Before sunrise the air is often nice and still, but once the sun appears it’s surprising how a breeze tends to follow it.

Four: You don’t have to shoot reflections in colour. Black and white works just as well and, in some cases, can be more effective because it simplifies the image even further.

Five: Forget about reality. Your aim isn’t to capture perfect reflections that mirror the real world but to make the reflection the subject. It doesn’t matter if what’s being reflected happens to be identifiable or not.

Six: Watch your exposures. Reflections by their very nature are created in surfaces that reflect a lot of light, so your camera’s metering system may be fooled into underexposure. If you’re shooting film, always bracket over the metered exposure by ½ and 1 stop. If you’re shooting digitally, check the histogram and increase the exposure if necessary because slight overexposure is preferable to underexposure.

RIVER COQUET, NORTHUMBERLAND, ENGLAND

GRASMERE, LAKE DISTRICT, ENGLAND

VENICE, ITALY

Reflections in water are like visual poetry. They’re delicate and dreamy and inspire positive thoughts. These images were all made at different times and in different places but they share the same feel, partly thanks to the natural softness of the lens on my old toy camera, but also because wherever you go in the world, water has the same magical, dream-like qualities.

CAMERA: DIANA F/LENS: FIXED 75MM/FILM: ILFORD XP2 SUPER

PHONE A FRIEND

If any modern gadget symbolizes the way technology has advanced in the last decade or so, it has to be the mobile phone (cellphone). I still remember the days when only the rich and successful could afford one, and they were so big you practically needed a wheelbarrow to transport them. Today, they’re small, light, cheap to own, and so, far from being an expensive luxury, they’re now considered to be an essential accessory. Almost everyone owns one – even my 11-year-old son.

Of course, they are no longer just phones. They’re multi-media consoles that allow you to listen to music, surf the net, send and receive e-mails, find your way from A to B and, you’ve guessed it, take pictures.

Their photographic potential is phenomenal when you think about it. It’s not that long ago that everyone was raving about 1MP digital cameras costing more than £1000 ($1750.00). Now you can pick them up as free upgrades on your contract with a phone boasting 5MP or more.

Okay, the sensors in phone cameras are very small, so a 5MP digital compact or SLR will outshine a 5MP phone camera in every way. But as a visual diary for photo blogs (see page 122) or simply for taking snapshots when you’re out and about, a decent phone camera is a very good choice.

ALNMOUTH, NORTHUMBERLAND, ENGLAND

If I hadn’t told you that these images were all made with a modest mobile phone (cellphone) camera, would you have guessed? Probably not. A phone camera will never be a viable replacement for a digital compact or SLR if you’re a serious photographer, but when used on the right subject the results are surprisingly good. If I ever found myself in a situation where the only means of taking a photograph was by reaching for my phone, I’d do it without hesitation.

CAMERA: SONY ERICSSON W880 2MP

In the field

To prove this, I decided to make the effort to take pictures using a mobile phone. I tried my own phone, but after a year of being bashed and dropped its 2MP camera has been rendered pretty useless. Every picture I took suffered from ugly colour banding and image quality was poor. I then tried my son’s phone. Not only was it a more recent model but also much less used and in better condition. The differences in the results were astonishing. They were clean, crisp, sharp and colourful, just like proper photographs taken with a proper camera.

Obviously, big enlargements from an image taken on a mobile phone are out of the question. Converting the 72dpi Jpegs captured by the camera into 300dpi Tiffs gave me images with an output size around 15 x 10 cm (6 x 4in). But actually, the kind of photographs you’re going to take with a phone camera are more likely to be used, viewed and shared electronically by text, e-mail, uploading to websites and so on, rather than printed. So, output size isn’t that important.

The key to making the most of your phone camera is accepting its limitations and working within them. Other than the ability to make an image lighter or darker by increasing or reducing the exposure, controls are minimal. It’s a case of pointing and shooting. But as I’ve proved with cameras such as the Holga (see page 142), this simplicity needn’t get in the way of creativity. In fact, it can encourage rather than hamper it.

Taking photographs with the phone had an ever-present element of unpredictability and surprise, which added to the experience. If a shot worked, it worked. If it didn’t, it didn’t. It also felt rather weird using a phone to take ‘serious’ photographs, but it was also quite liberating at the same time.

The most frequent mistake that I made was trying to get too close to the subject. With no viewfinder to rely on, and no facility to prevent the camera’s shutter firing even if the subject wasn’t sharply focused, I got rather carried away, only to discover that lots of the images that I thought would work really well were actually out of focus.

Fortunately, enough of the images were successful, and they convinced me that there definitely is a place in my photographic life for a phone camera. All I have to do now is wait another nine months so I’m eligible for a free phone upgrade. But, who knows? By then the resolution may have reached 10MP.

POCKET POWER

Compact cameras are often seen as second rate compared to the more sophisticated single lens reflex (SLR) cameras. In a sense they are. SLRs have more features, usually offer greater control, can be fitted with a wide range of interchangeable lenses and, in most cases, offer superior image quality. But one thing compact cameras have going for them that SLRs don’t is their small size.

Although there are exceptions, the vast majority of compact cameras are small enough to slip into a pocket and carry everywhere. That means wherever you go, you will always have a camera to hand to grab those fleeting photo opportunities that would otherwise be missed. Compact cameras also make great visual notebooks. You can use one to take shots for future reference, such as reminders of good locations, for example, or an idea for an image or project that suddenly comes to mind.

I admit that I always used to turn my nose up at the idea of a compact camera. Why bother with one when an SLR will produce superior results? Then 18 months ago I invested in a Sony Cybershot and my perceptions changed forever.

Small but perfectly formed

It was purchased primarily so that everyone in my family could take snapshots on holidays, special occasions and Sunday strolls. However, I soon realized that my new toy had much more to offer, and the more I used it, the more impressed I became with the results it was capable of producing.

With only six mega-pixels crammed into a tiny sensor, it will never be good for poster-sized prints. But how often do you print anything that big? Even when my images are published in books and magazines the majority are much smaller than full page.

To put this to the test, I started using the camera as a serious tool, taking it away on shoots and using it alongside my other equipment to see how it compared. Or I just took the compact out to see what I could produce with it. I even organized a workshop for a magazine to which I contribute where the readers involved were only allowed to use a digital compact camera. We were all operating well outside our comfort zones, without tripods, filters or any of the other paraphernalia we’re used to. However, we spent an enjoyable afternoon snapping away, and the results surprised everyone.

What I found is that freed from the constraints imposed by bigger, heavier and slower equipment I was much more open-minded about what I shot. If I tried something and it didn’t work out, the image could be erased forever and I would move on to the next idea. I also felt less self-conscious when I was taking pictures around other people because the general perception is that compacts are for snaps and serious photographers use fancy SLRs with big lenses.

One one occasion I photographed a sign outside a large furniture store. There’s no way I would have done that with a tripod and SLR in the full glare of the public and passing traffic, but with a compact I could be much more discreet and no one seemed to take any notice whatsoever.

Here are just a few of the many photographs I’ve taken using my go-anywhere digital compact. As you can see, it’s a versatile piece of kit that can cope with a range of subjects and lighting conditions, from a winter sunrise and backlit deckchairs to colourful abstracts and contrasty interiors.

CAMERA: SONY CYBERSHOT 6MP/LENS: FIXED 6.3-18.9MM ZOOM

Go with the flow

The key when shooting with a compact is to work with the limitations imposed by the camera rather than fighting against them. You don’t get ultra-wide or super-telephoto lenses on compact cameras, so steer clear of subjects that require them. You have no control over depth-of-field, so don’t bother trying to get everything sharp from a few centimetres to infinity. If the exposure and metering are fully automatic, don’t shoot in really tricky light, or if you do, accept that the camera may struggle.

Digital compacts are actually surprisingly good when it comes to getting the exposure right and coping with high contrast. A growing number of models also give you the option to shoot in RAW capture mode, which means you can adjust exposure, contrast, colour and more when the files are downloaded to a computer and processed.

Using filters is possible but fiddly. A polarizer can be rotated into prime position then held in front of the lens while a picture is taken, and securing grad filters with small blobs of putty adhesive isn’t out of the question. But to be honest, I never bother. Instead, I concentrate on subjects and scenes where filters are unnecessary, such as abstracts, patterns, textures and details. I’m not interested in producing images with a compact that I would normally shoot with a digital SLR or medium-format film camera. I want to look at the world through different eyes and, hopefully, come up with images that are fresh, spontaneous and exciting.

If you need to put any of those things back into your own photography, you could do a lot worse than downsize and get creative with a compact.

PIN SHARP

Like the vast majority of photographers, I tend to take modern technology for granted. I’ve grown accustomed to cameras that boast sophisticated integral metering, numerous exposure modes, lightning-fast focusing and, more recently, a digital sensor with phenomenal resolving power.

But what was it like for the early pioneers of photography? They had none of these things yet still managed to create beautiful images. Eventually, my curiosity got the better of me and I decided to find out by taking a step back in time and working with a pinhole camera, the simplest picture-taking tool there is.

ST MICHAEL’S MOUNT, CORNWALL, ENGLAND

This photograph was taken at dawn on a very dull, cloudy day. Light levels were low, which meant using a long exposure. Consequently, motion in both the drifting cloud and incoming tide has been recorded and adds atmosphere, while the concrete jetty leads the eye through the scene to St Michael’s Mount in the distance. The deep blue cast is a result of the dull weather and reciprocity failure brought on by the long exposure.

CAMERA: ZERO 2000/FOCAL LENGTH: 25MM/FILM: KODAK PORTRA 160 VC

Pinhole cameras represent picture-taking in its most primitive form. You can’t find a more basic way of taking a photograph than using a light-tight box with a tiny hole in the front that projects an upside-down image onto a sheet of silver-coated material placed inside it. It’s where this magical art form of photography began, in the 19th century, and taking a look back at its origins is fascinating, inspiring and humbling.

Technology has come a long way since then, but you can still create wonderful images that have character, soul and individuality without relying on any of it. More importantly, the lessons learned from working with absolutely basic tools are bound to benefit your photography in general.

BLYTH PIER, NORTHUMBERLAND, ENGLAND

I also use a 5 x 4in pinhole camera, mainly so I can work with Polaroid Type 55 pos/neg film (see page 53). As it is an instant peel-apart film I get to see the results immediately, though my main reason for using this film is its wonderful image quality and the distinctive border around the edge of the negative.

CAMERA: ZERO 2000/FOCAL LENGTH: 25MM/FILM: ILFORD XP2 SUPER

Point and shoot

The mechanics of using a pinhole camera are fundamentally the same as using any film camera, though its simplicity does impose certain limitations on how an image is made, and will stamp certain characteristics on that image.

For a start, there is no viewfinder to assist you in composing a photograph. You could make a compositional aid by using some black card or plastic that’s held in front of your eye to give you an idea of the camera’s field of view. However, I prefer to simply point and shoot.

It’s surprising how accurately you can compose an image without the aid of a viewfinder, once you’ve had a little practice. And it’s refreshing to work in such a simple way. As for wonky horizons, well, a small level placed on top of the camera easily solves that problem.

The pinhole acts as both lens and aperture and, because it must also be as small as possible to ensure the final image is relatively sharp, long exposure times of anything from 1/2sec in bright sunlight to several minutes at dawn and dusk on medium-speed film are unavoidable. This makes a tripod essential to keep the camera steady (a good thing because it aids accurate composition) and also means that any motion during exposure will record as a blur.

This is one of the main features of a pinhole image, and the one I like most. It’s best revealed in seascapes, where long exposures allow the ebbing and flowing of the waves and the drifting of the clouds to record as gentle mist. Urban scenes also work well with people and traffic crossing through the scene during exposure.

Calculating exposure is easier than you’d imagine. If you know the f/number of your pinhole (it’s f/138 on my Zero 2000 camera) you can take an exposure reading with a camera or hand-held meter then double the exposure time for each f/stop reduction. For example, if the metered exposure is 1/2sec at f/22 it will be 1sec at f/32, 2sec at f/45, 4 sec at f/64, 8 sec at f/90 and 16sec at f/128, which is close enough to f/138 in my case.

Once exposures get beyond a few seconds, reciprocity failure kicks in and can cause underexposure. I don’t worry about it if the calculated exposure is fewer than 30 seconds because the exposure latitude of colour negative film, which I choose over colour slide film for pinhole work, takes care of it.

Once the calculated exposure is beyond 30 seconds I do increase it by 50 per cent for exposures of 30–60 seconds and 100 per cent for exposures of over 60 seconds. You don’t have to be accurate to the second here, so I either count elephants in my head or, for really long exposures, I use my wristwatch to keep track.

Where pinhole photography gets tricky is in bright sunlight when the calculated exposure is only 1/4 or 1/2sec. This is because if you have to open then close the shutter quickly there’s a risk of jerking the camera and producing a shaky image. To avoid that, I use either a polarizing filter or a neutral density filter to increase the exposure, so 1/2sec becomes 2sec with a polarizer or 0.6ND filter, which is easier to execute. The filter itself is simply secured with blobs of adhesive putty in front of the camera. Crude but effective.

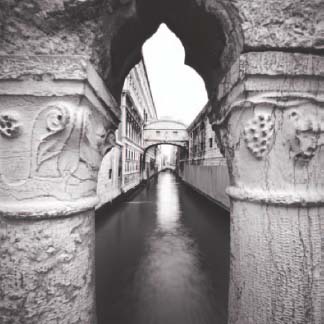

BRIDGE OF SIGHS, VENICE, ITALY

For this view of the much-photographed Bridge of Sighs, I placed the camera just 7.5–10cm (3–4in) from the carved stone pillars so the bridge would be visible through the narrow gap. Endless depth-of-field and an ultra wide-angle view made this possible. Such an image could not be achieved with a normal camera.

CAMERA: ZERO 2000/FOCAL LENGTH: 25MM/FILM: ILFORD XP2 SUPER

Here to infinity

As well as long exposures, pinhole cameras also give you an ultra-wide angle of view and endless depth-of-field, two factors that can be put to great use.

The focal length of my Zero 2000 camera is 25mm, which on 6 x 6cm format roughly equates to around 16mm. Such an extreme angle of view can easily result in empty compositions. Fortunately, because the effective aperture is so small, depth-of-field extends from just a few centimetres to infinity. This means that empty compositions can be avoided by getting in really close to nearby features so they dominate the foreground and create a dramatic sense of perspective and scale. Converging lines in a scene created by paths, railing, jetties and piers can be especially effective and can also be exploited.

Using a pinhole camera for the first time is a weird experience simply because it’s so unlike any other type of camera you’ll ever encounter. The lack of a viewfinder is particularly disconcerting because with no way of setting up the shot accurately you’ve got no idea how it’s going to turn out. But just following your instincts and hoping for the best is all part of the fun.

One thing’s for sure; the results are rarely a disappointment. Although I’ve finally taken the plunge and invested in a digital SLR system, my Zero Image pinhole camera still has a permanent space in my backpack because, despite all the benefits modern technology has to offer, it’s refreshing to turn your back on it once in a while and go back to basics.

PIENZA, TUSCANY, ITALY

The lack of a viewfinder needn’t be an obstacle when using a pinhole camera. Just follow your instincts and see what happens. The results are never quite what you expect.

CAMERA: ZERO 2000/FOCAL LENGTH: 25MM/FILM: KODAK PORTRA 160 VC

ISLE OF LEWIS, OUTER HEBRIDES, SCOTLAND

Because the angle of view of most pinhole cameras is very wide, you must include foreground interest otherwise the composition will appear empty and boring.

CAMERA: ZERO 2000/FOCAL LENGTH: 25MM/FILM: KODAK PORTRA 160 VC

GLENCOE, HIGHLANDS, SCOTLAND

The lake in the foreground of this scene was nothing more than a small puddle, but I set up the camera so it was only centimetres above the water. The extreme angle of view of the pinhole stretched perspective to make it seem huge.

CAMERA: ZERO 2000/FOCAL LENGTH: 25MM/FILM: ILFORD XP2 SUPER

PUBLISH OR BE DAMNED

There can be few things more exciting to a photographer than seeing their work in print. It’s the ultimate confirmation of success. I’ll never forget the first time I had my own images published in a photographic magazine in the mid-1980s. It was such an exciting, pivotal moment in my life. Since then I’ve had thousands of photographs published and written hundreds of magazine articles and 16 books on photography, but I still get the same buzz when I open a publication and see my work on the printed page.

TRAVELS WITH A TOY CAMERA – CUBA

To try out the Lulu POD service, I created my own book using images shot in Cuba in 2006 using a Holga toy camera (see page 142). I had never done anything like this before, but I found the on-line instructions at www.lulu.com easy to follow. The book was designed using Adobe InDesign, which I had as part of Creative Suite CS2. Again, I had never used this software, but it was very intuitive and in the space of an afternoon my 58-page book was complete. After converting the document into a PDF file, again using Adobe InDesign, I uploaded it to www.lulu.com, created an account and profile so the book could be sold via the website and ordered a few sample copies. So far I have sold 59 copies. It is not a huge amount, but it’s heartening to know that other photographers around the world logged on to the Lulu website, found my book and thought it was good enough to buy. Check it out yourself by entering Lee Frost into the search window at www.lulu.com.

When I first became interested in photography, publishing books was the preserve of a tiny minority who either had the financial backing of a publisher or were wealthy enough to fund their own expensive self-publishing projects. I was lucky and got the former, though still can’t afford the latter!

Today, however, thanks to advances in digital technology and the rise of Print on Demand (POD) services, you don’t need either. Anyone can publish a book of their work for minimal, in some cases zero, outlay. The way printing used to work, it was only financially viable to publish a book if you printed a large volume, meaning thousands, of copies. Printing plates had to be created for each page of the book and the printing press set up for each job, which is a time-consuming and costly exercise. But with digital printing machines no setting up is required. Pages are printed from digital files, making small-run printing possible.

Print on Demand, as the name implies, involves printing something only when an order is received – even just one copy at a time if necessary. So, you could design a book of your work (or pay someone to do that job for you), have a few sample copies printed for promotional purposes, and then only reprint when copies have been ordered and paid for. To make life even easier, there are now a growing number of POD publishers around that not only print the books as and when required, but will also market and sell it on your behalf, paying you a royalty on each copy sold.

The best-known POD publisher is Lulu (www.lulu.com). To produce a book with Lulu, the first step is to create an online account, choose a book format from one of the options available and decide how many pages you want. Then you can use a cost calculator on the website to establish how much it will cost to produce each copy.

Lulu doesn’t offer a design service or design software, but you can use any proprietary design software, such as QuarkXpress or Adobe InDesign. You just need to be able to convert the finished layouts into a print-ready PDF file, which can then be uploaded to the lulu.com website ready for printing. All this is completely free of charge. You only pay when you place an order for copies of the book, though you’re under no obligation to do so.

The smart thing about Lulu is that as well as printing your books it will also sell them via the lulu.com website. You can specify the retail price of the book so that you make a profit on each sale. Orders are placed directly with Lulu, copies are printed and shipped by them (you don’t have to do anything) then every few months royalties are paid to you on any sales achieved.

You’re not going to get rich by publishing books via lulu.com, but it’s a fantastic concept and well worth trying out if you want to see your work in print.

This is the profile page for my Cuba book on the Lulu website. When you enter information about a book, keywords can be used to increase the chance of it coming up in a search and thereby maximizing sales.

A preview of the book can also be created, allowing potential buyers to sample a few pages before they decide to place an order.

RED ALERT

Light is the raw ingredient of photography. Without it, the art of image-making wouldn’t exist, and we’d keep bumping into things.

But the light we actually work with covers a very limited range because so-called normal photographic films – and most digital camera sensors – are only designed to record light in the visible spectrum. Beyond it, there’s a vast, invisible world that we will never be able to see with the naked eye.

Look at a diagram representing the electromagnetic scale. It starts off purple (ultraviolet) at one end, gradually warms to form the visible spectrum, the bit we can see (think rainbow) before turning red and then infrared.

Photographically, it’s possible to record the effects of infrared light using infrared-sensitive films such as Kodak HIE and Ilford SFX. Over the years I have exposed dozens, if not hundreds, of rolls of these films and, when handled properly, they can produce utterly amazing images.

That said, infrared film is tricky to work with. It’s prone to fogging by visible light. The effective ISO varies depending on the light and weather conditions you use it in, so exposure bracketing is essential. You must shoot through a deep red or opaque infrared-transmitting filter, and the negatives require very careful printing to get the best from them. I should know – I’ve spent many a night locked away in my darkroom trying to tease successful images from dense infrared negatives. I also know that the complications of using and printing infrared film have been enough to put many photographers off ever bothering to try.

Fortunately, it’s now possible to record infrared light digitally using a modified digital SLR or compact camera and to produce stunning images in a matter of minutes. So if you’ve ever been discouraged from exploring the fascinating world of infrared photography in the past because it seemed too much like hard work, now’s your chance to change all that.

VITALETA, TUSCANY, ITALY

This image is a good example of what you can expect from an infrared-modified camera. The IR sensitivity has really brought out the drama in the evening sky, while the field of dry grass in the foreground has recorded in its characteristically light tone. Stunning.

CAMERA: NIKON D70 IR CONVERSION/LENS: 10-20MM/ISO:200

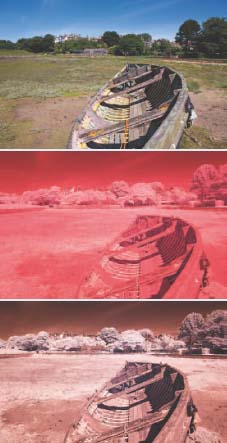

ALNMOUTH, NORTHUMBERLAND, ENGLAND

Adding Diffuse Glow to a duplicate layer really heightens the infrared effect by enhancing the highlights. It’s a technique I now use on all my infrared images in varying degrees.

CAMERA: NIKON D70 IR CONVERSION/LENS: 20MM/ISO:200

Seeing red

I had my first digital SLR modified to record infrared light back in April 2008, and from the very first outing with it I was hooked.

Compared to shooting infrared film, digital infrared photography is simplicity itself. The results are as good as film images – in fact, better in many respects – but much easier and quicker to achieve. It would have taken me hours on end to print just a handful of infrared negatives, whereas now I can download and process dozens of digital infrared images in the same amount of time.

Modern modifications (see panel opposite) are done in such a way that you don’t need to bother putting a deep red or infrared-transmitting filters on the lens, as was necessary when working with infrared film. Nor do you need to worry about the fact that infrared light focuses on a different point to visible light and adjust focus accordingly because the camera’s focusing system is adjusted internally to compensate.

In practice, what this means is that you can use an infrared-modified digital camera like any digital camera. Even the exposures are hardly different. The difference is in the images that result: they’re worlds apart.

In the infrared spectrum, the way things appear depends on the amount of infrared radiation they reflect. Water and blue sky record as very dark tones (often black) because little IR radiation is reflected, whereas foliage and grass reflects a lot of infrared light so it records as a very pale, almost white tone. Similarly, if you shoot portraits with an infrared camera, skin tones record as a pale, ghost-like tone while the eyes appear dark – a spooky combination that can work well.

Use an infrared-modified camera for interior shots, as I have done, and often it’s hard to see any trace of an infrared effect. Similarly, if you shoot outdoors in bad weather and exclude anything from the composition that would normally show the infrared effect, such as foliage, the images will appear just like dramatic black and white photographs.

NEAR SAN QUIRICO D’ORCIA, TUSCANY, ITALY

Bright sunlight, blue sky and fluffy white clouds are the ideal ingredients for infrared photography. In this scene I particularly like the way the two cypress trees on the hill have recorded as silhouettes because a cloud momentarily blocked the sun from view, throwing them into shadow.

CAMERA: NIKON D70 IR CONVERSION/LENS: 10-20MM ZOOM/ISO:200

CALLANISH, ISLE OF LEWIS, OUTER HEBRIDES, SCOTLAND

Even though you can produce great infrared images at any time of day, my favourite periods are early morning and evening when the sun is low in the sky, shadows are long and light sweeps across the landscape.

CAMERA: CANON 20D IR CONVERSION/LENS: 16-35MM ZOOM/ISO:100

LUCIGANO D’ASSO, TUSCANY, ITALY

An interesting side-effect of digital infrared photography is the way cameras record false colour. In 99 per cent of cases it looks odd and I desaturate the image to get rid of it, but occasionally I take a picture and the false colour really enhances it, as in this shot of an old Tuscan village.

CAMERA: NIKON D70 IR CONVERSION/LENS: 10-20MM ZOOM/ISO:200

WHITLEY BAY, TYNE AND WEAR, ENGLAND

In bad weather, with no foliage in the scene to show the effect, photographs taken with an infrared-modified camera tend to just look like stark black and white images, though I actually like the effect and find it easier to shoot digital black and white this way than by using an unmodified digital SLR to produce colour images that are subsequently converted to black and white.

CAMERA: NIKON D70 IR CONVERSION/LENS: 10-20MM ZOOM/ISO:200

NOAH, NORTHUMBERLAND, ENGLAND

This is the very first digital infrared picture I ever took. My son and his friend were having a water pistol battle so I wandered over and grabbed a few quick snapshots, just to see how they would look. Notice the way skin tones record as a pale tone while eyes look dark and menacing.

CAMERA: NIKON D70 IR CONVERSION/LENS: 20MM/ISO:200

Suitable subject

In terms of subject matter, anything goes, really. Whenever I’m out shooting I carry my infrared-modified Canon 20D with me and if I see anything that might make an interesting infrared image then I’ll photograph it. Because the camera can be used hand-held, it’s quick and easy to fire off a few frames. And if they don’t work, I have lost nothing.

Landscapes are an obvious choice because any scene containing foliage and plant life will exhibit strong infrared characteristics. Woodland is another contender, especially in spring when lush, green foliage records like delicate white snowflakes. I also enjoy shooting old deserted cottages or crumbling castles and monuments because the haunting look of infrared suits them perfectly, especially when ivy or other creepers grow around the doors and windows. In towns and cities anything graphic – modern architecture, bridges and sculpture – works really well.

Bright sunlight provides the best conditions for infrared photography because the light is crisper and contrast is high. There’s a greater concentration of infrared radiation for your camera to record, so the effect is stronger. Actually, one of the great things about infrared photography is that you tend to get the best results around the middle of the day when the light is harsh, which happens to be the worst time of the day for colour landscape photography. Consequently, you can pack your normal camera away and shoot infrared images instead, thus minimizing any down time due to a deterioration in light quality.

The same applies in bad weather. If the light is flat and the landscape appears grey and lifeless, don’t pack up and head home, just reach for your infrared camera. The images may not be obviously infrared, but as dramatic black and white photographs they will work wonderfully and, once again, you’ve made the most of an unpromising situation.

The images in this chapter will give you an idea of what’s possible. I’ve only been shooting digital infrared for a few months, but already I have hundreds of successful images. Wherever you go, and whatever the weather, you will always find that there’s a great infrared shot to be taken.

So if you’ve recently upgraded your digital SLR and were wondering what to do with its predecessor, now you know. Instead of selling it on eBay for peanuts, send it off for infrared modification and breathe new life into your photography.

GATESHEAD, TYNE AND WEAR, ENGLAND

Creating stitched panoramas with an infrared-modified camera is just the same as with a normal camera. For this view of Newcastle Quayside from Gateshead, I shot a sequence of eight overlapping frames, stitched the RAW files using Photomerge in Photoshop CS3, then made any adjustments necessary to achieve the final effect.

CAMERA: NIKON D70 IR CONVERSION/LENS: 20MM /ISO:200

REPEAT AFTER ME

Everything we do follows a pattern of some kind, from the way we mow the lawn or brush our teeth to the daily routine of our lives – get up, shower, dress, eat breakfast, go to work …

We can’t survive without repetition. It creates order from chaos, which in turn brings us strength, stability and reassurance.

The same holds true for photography. Patterns are powerful because they attract attention and hold it. They engage the brain and stimulate the senses. Put one car in a parking lot and you have one car in a parking lot, but put another 20 cars next to it and a strong pattern emerges because cars, regardless of make or model, all look very similar. It’s the same with telephone poles lining the street, chimney pots on rows of Victorian terraced houses, balconies on a Mediterranean hotel, faces in a crowd, stones in a wall, soldiers on parade, shoes on a market stall, sun loungers on a beach … Get the idea?

A telezoom lens is perhaps the best tool for shooting patterns because you can isolate details that are in the distance and exclude all unwanted information from the frame to reveal the pattern in its most powerful form. Telephoto lenses also compress perspective and it is this characteristic that will emphasize pattern by making the repeated features in a scene seem closer together than they are in reality.

Often patterns will be so obvious that you can’t avoid noticing them. However, the patterns that make the best pictures tend to be those that are more hidden and need a bit of effort from you.

The best way to spot them is by distancing yourself visually from whatever you’re looking at. So, instead of seeing something purely for what it is, you need to look at the lines, shapes, colours and objects within it. In other words, you need to learn to view the world in an abstract way, because patterns are essentially abstracts – small parts of a much bigger picture.

CAMERA: NIKON F5 AND NIKON F90X/LENS: 105MM MACRO AND 80-200MM/FILM: FUJICHROME VELVIA 50

ROCK STARS

Living just a few minutes away from the Northumberland coast, and leading photo workshops around the UK, I spend an increasing amount of time by the sea. There I take photographs – and help others take photographs – of some of the most beautiful coastal scenery you’ll find anywhere.

Unfortunately, as all keen landscape photographers in the UK know only too well, our fickle weather often gets in the way of art. Long spells of inactivity while waiting for the light to improve are commonplace.

Now, I’m not the most patient soul and after ten minutes of twiddling my thumbs I start to get restless. I’m also aware that when photographers have paid a lot of money to join a workshop and have spent months looking forward to it, the last thing they want to do is sit around because the weather’s dull and grey and the classic views we’ve set out to shoot have lost their sparkle.

To counter this, I always try to have alternative subjects and locations up my sleeve that suit dull weather. This is not only so that we can remain active, but also because I feel it’s important that photographers work outside their comfort zone and explore different subjects, techniques and styles. It’s the only way to develop creatively and improve your eye for a picture. There are numerous grey day options, such as woodland, any form of moving water or old buildings, depending where you happen to be. However, whenever I am shooting on the coastline, the top of my list has to be rock abstracts.

Beaches and intertidal zones are full of fascinating geology, and include everything from jagged cliffs and amazing rock strata to sea-worn boulders and eye-catching erratics. Once you start to explore the wonderful variety of shapes, textures, colours and patterns they offer, it’s amazing how many photographs can be taken in a relatively small area.

Erratic actions

When I set out to photograph rock details, there’s no rhyme or reason to what I do. It’s simply a case of wandering around and looking, looking a little closer, putting the camera and tripod down and trying to create something interesting in the viewfinder.

The composition could be based on colours, shapes, textures or a combination of all three. I don’t intentionally set out to exclude all traces of scale but often find that I do so instinctively. This gives the resulting images an extra level of interest because it’s not always obvious what you’re looking at.

I have a particular penchant for sea-worn boulders. I find their smooth shape incredibly photogenic, especially when contrasted with rougher shapes and textures. I can also while away hours looking for stones that have been thrown up by the tide and jammed into rock cracks, or single pebbles and boulders left stranded on rocky shelves by heavy seas. And though I hate to say it, if I don’t find what I’m looking for, I’m quite happy to create it by moving rocks around to form interesting arrangements. Just think of them as outdoor still-lifes.

PORTH NENVEN, CORNWALL, ENGLAND

SANDYMOUTH, CORNWALL, ENGLAND

TARANSAY, OUTER HEBRIDES, SCOTLAND

These images were made in three different coastal locations and show how the simplest subject matter can make a highly effective image if you treat it as a series of colours, shapes, textures and patterns rather than just a few old rocks. As well as working individually, the images are even more striking as a set because they’re united by a common theme.

CAMERAS: MAMIYA C220 TLR AND BRONICA SQA/LENSES: 80MM AND 150MM/FILM: FUJICHROME VELVIA 50

The most interesting area to work in tends to be the zone that’s underwater at high tide but revealed when the tide is low, simply because it’s in a constant state of flux. After a particularly strong tide, rock arrangements that have existed for days, weeks, even years can be washed away forever, only to be replaced by new ones. Every visit presents new opportunities, simply because little stays the same from one day to the next.

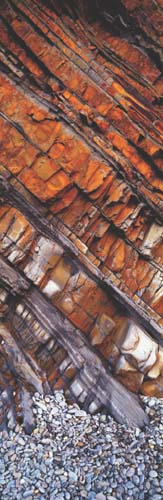

SANDYMOUTH, CORNWALL, ENGLAND

The beach at Sandymouth is an amazing location for rock abstracts, and you could easily spend days there. I used a panoramic camera in upright format for this shot to emphasize the dramatic diagonal strata in the cliff face. Including pebbles at the base of the cliffs adds scale and shows that the strata literally rise from the beach in gigantic slabs.

CAMERA: FUJI GX617/LENS: 90mm/FILTERS: 0.3 CENTRE ND/FILM: FUJICHROME VELVIA 50

ISLE OF EIGG, SMALL ISLES, SCOTLAND

Rocks and boulders don’t have to simply be a source of abstract and close-up images – they can also be used as foreground interest in wider views. This limpet-encrusted rock caught my eye while exploring Laig Bay on the island of Eigg. It was sitting in its own sandy hollow and created strong interest in what was otherwise a flat and empty beach.

CAMERA: CANON EOS 1DS MKIII/LENS: 16-35MM/FILTERS: 0.9 ND HARD GRAD

PORTH NANVEN, CORNWALL, ENGLAND

Rock details also work well in black and white because the removal of colour strips them down to the bare essentials of pattern, texture and form.

CAMERA: COSMIC SYMBOL 35MM RANGEFINDER/LENS: FIXED 40MM/FILM: ILFORD XP2 SUPER

PORTH NENVEN, CORNWALL, ENGLAND

SANDYMOUTH, CORNWALL, ENGLAND

TARANSAY, OUTER HEBRIDES, SCOTLAND

Rocks and boulders don’t have to be simply a source of abstract and close-up images. They can also be used as foreground interest in wider views.

CAMERAS: MAMIYA C220 TLR AND BRONICA SQA/LENSES: 80MM AND 150MM/FILM: FUJICHROME VELVIA 50

Softly softly

My preferred light for shooting rock details is created by bright overcast weather that is characteristically low in contrast so colour and tone are fully revealed but neutral in colour temperature so the delicate colours in the rocks record as seen without the need for filtration. That said, I will shoot no matter how drab, grey and damp the weather gets because it will still produce great pictures, in black and white as well as colour.

When I first started shooting rock details and abstracts, it was almost as a consolation prize. It was just something to do when the light wasn’t good enough for ‘proper’ landscapes. What I’ve come to realize along the way, however, is that far from being a poor relation to the grand view, these intimate images are every bit as interesting because ultimately, landscape photography is about one thing – rock. Even our very own planet Earth is known as the Third Rock from the Sun.

MAKE YOUR OWN REFLECTIONS

MAKE YOUR OWN REFLECTIONS