Many years ago, when I was enrolled at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, I had the good fortune to meet Harold Horwood. Harold was a well known Newfoundland writer and historian. He had come to the University of Waterloo as writer-in-residence. I was a member of a writers’ group in the Department of Integrated Studies, so naturally I invited Harold to come to one of our meetings.

Harold and I became friends and ended up collaborating on a book about Canadian outlaws. He had done considerable research on the pirates who had once prowled the waters off Newfoundland and the Maritimes Provinces, which perfectly complemented my own research on Canadian outlaws. Through Harold’s chapters I became familiar with such fascinating characters as the pirates Peter Easton and Eric Cobham.

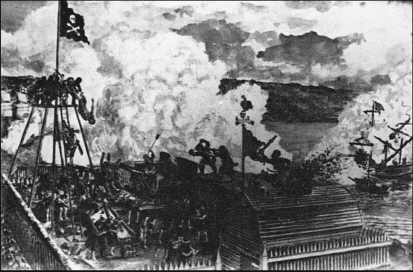

Easton built a pirate fort at Harbour Grace in 1611 and used it as a base to raid the Spanish Main. He and his pirates fought a battle with the Basques at Harbour Grace; the pirates who were killed in the fight were buried nearby, in a place that is still called the Pirates’ Graveyard. It is the only known pirate burial ground in North America, and I would not be at all surprised to hear that it is haunted. Easton was one of the most successful pirates who ever lived, and retired an extremely wealthy man.

Eric Cobham lived about a century after Easton. His principal partner in crime was Maria Lindsey, who was notorious for her cruelty. Using Bay St. George as a base, Cobham hijacked fur ships coming down from Quebec. The furs were then sold at great profit on the black market. Cobham was never caught. He got away with his robberies because he didn’t leave witnesses: he murdered the crews and sank the captured ships once they’d been looted. The ship owners would assume the missing vessel had been lost in a storm. Cobham eventually retired to a life of luxury in France; Maria Lindsey went insane and committed suicide by leaping off a cliff into the sea. In other versions of the story, she was actually pushed by Cobham. Toward the end of his life, Cobham confessed to his crimes and arranged to have his life story published posthumously. His family attempted to suppress the book, but a copy eventually found its way into the French archives.

A battle at Peter Easton’s pirate fort at Harbour Grace. The slain pirates were buried at a nearby site that is still called the Pirates’ Graveyard. It is the only known burial site of its kind in North America.

We are all familiar with stories of buried pirate treasure. Supposedly, any pirate worth his salt left at least one chest of gold doubloons buried in the sand somewhere. The pirates of legend, Captain Kidd, Blackbeard, Bartholomew Roberts, and Edward Low, were all said to have taken the secret locations of hoarded loot to their graves. In many of the tales, the pirate captain kills a member of his crew and buries the body with the treasure, so that the dead pirate’s ghost will guard it.

While some pirates may have stashed gold and silver away in hidden places, most of these stories are based on myth. In fact, it is largely the invention of novelists like Robert Louis Stevenson, author of the classic Treasure Island. Pirates generally squandered their ill-gotten gains on rum, women, and gambling. They lived for the moment with little thought for tomorrow, especially since tomorrow might bring death in battle or on the gallows.

But legends, like the pirates themselves, die hard: treasure hunters are still searching for the plunder of Captain Kidd and his pirate brethren. And then there’s the story of Shellbird Island in the Humber River, near Corner Brook. Shellbird Island, which lies below a natural rock formation resembling a human face, is a legendary site of buried pirate treasure. And both Peter Easton and Eric Cobham are historically associated with the island.

The Cobham connection is based on the story that nearby Sandy Point was his principal lair. However, there have been other, more compelling arguments that the treasure, if it is there at all, was left by Peter Easton. According to these accounts, Easton didn’t confine his pirate raids to the Spanish Main but also hit the fur-bearing ships coming from Quebec. During one of his raids, Easton was forced to withdraw due to the sudden appearance of a French warship.

Deeming discretion the better part of valour, and hoping to evade capture, Easton sailed to the mouth of the Humber River to hide. Legend has it that Easton sent his first mate and a sailor to Shellbird Island with three treasure chests. The men buried them in three different spots. At the third location, as the sailor was about to fill in the hole, the first mate killed him, and dumped the corpse into the pit, thus providing the required ghost to do duty as a sentinel. However, bad luck befell the first mate. At the Devil’s Dancing Pool on the Humber River his boat overturned and he was drowned. Easton didn’t know the exact location of the treasure sites. He searched for them, but never found them.

For centuries the treasures lay undiscovered. Then, according to one story, late in the nineteenth century some lucky fortune hunters found one of the chests and secretly divided up the loot. In 1934 it was rumoured that the second chest had been found. Again, the riches in it were secretly shared among the fortunate few.

When Harold Horwood and I were collaborating on our book, he didn’t mention anything about the treasure and ghost stories to me. Perhaps he wanted to stick to what he considered the cold, hard facts. Nonetheless, I was thrilled to come across this legend connected to Peter Easton. Maybe the third treasure chest still lies hidden, guarded by the ghost of the murdered pirate. The Shellbird Island story is but one of many swashbuckling Newfoundland and Labrador tales of blood, buried treasure, and ghosts.

In the first quarter of the eighteenth century, the period known as the Golden Age of Piracy, many freebooters were drawn to the coast of Newfoundland. Its hidden coves were excellent places in which they could repair and careen their ships, and stock up on food and fresh water. They could also recruit men — both willing and unwilling — from the fishing stations. If there is truth to the legends, these coves were perfect spots in which to stash away plunder. Treasure Cove on the north side of Torbay Harbour, a few miles north of St. John’s, is one such location.

According to a very old story, an unnamed pirate captain sailed into Torbay after a successful summer of raiding the Spanish Main. He decided that the isolated cove would be a perfect place to deposit some of his stolen gold, silver, and jewellery. He called on his crew for volunteers to go ashore with him to help bury the loot and mark the site. The crewmen were veteran pirates, and they knew that anyone who went off with the captain was not likely to come back. However, there was a boy on board who had been taken off a captured ship and pressed into service as a cabin boy. This lad, perhaps thinking he would get into the captain’s good graces, volunteered. Maybe the captain would even remove the fetters from his hands and feet. None of the pirates dared to warn him of the danger.

When the captain and the boy prepared to set off in the ship’s boat with a chest full of riches, another passenger joined them: a big Newfoundland dog that was the ship’s mascot. During his captivity the boy had befriended the dog. As the ship’s boat was about to shove off, the dog jumped into it. Considering the dog to be his obedient beast, the captain was unconcerned.

Somewhere in the woods near the shore of Treasure Cove, the obliging cabin boy helped the captain dig a deep hole while the dog sat watching. The unsuspecting youngster had just assisted the captain in lowering the treasure chest into the pit, when the pirate suddenly drew his cutlass and, in one slash, decapitated him. The body and the head dropped into the hole, coating the chest with blood.

The enraged Newfoundland dog snarled, bared its teeth, and leapt at the captain. Even though the pirate was startled, he was too fast for the dog. Another slash with the cutlass, and the big dog was dead. The captain tossed its body into the hole along with the murdered boy. He filled in the hole and returned to his ship.

The villainous captain never came back to pick up his buried loot, though. He might have been killed in battle, drowned in a storm, or hanged on a gallows. The secret of his treasure died with him. The burial site was just another lonely spot on a wild coastline.

That is until, one night many years later, two Torbay fishermen landed on the beach at Treasure Cove. They had heard the beach was haunted and were unnerved by it. But the weather was bad, and they had a boatload of fish.

The fishermen had barely set foot on dry land when a big Newfoundland dog came bounding out of the woods toward them. At first they thought that it must belong to a local family. But as it drew nearer, they could see that its eyes glowed with a hellish red fire. Then behind it, with chains rattling on hands and feet, came the headless ghost of the cabin boy.

The terrified fishermen put their backs to the dory, and in spite of the dark and the foul weather, they pushed off and manned the oars. The horrible apparitions pursued them as far as the water’s edge. The men made it home safely, but because they had seen the headless ghost and the phantom dog, they were cursed. One of them soon suffered an accident that made him an invalid him for the rest of his life, and the other one died within the year.

About 250 years ago, a pirate captain was cruising off the southeast coast of Newfoundland hoping to waylay an unsuspecting merchant vessel bound for St. John’s. In his hold was the loot from earlier captures. To the captain’s horror, the ship that suddenly hove into view was not a defenseless merchantman, but a British man-o-war. No pirate ever chose to shoot it out with the Royal Navy if there was a chance to escape. With the warship bearing down on him, the pirate captain turned toward shore, seeking shallow waters where the larger ship could not follow.

This was not the pirates’ lucky day. They ran aground on the deadly shoal at the entrance of the appropriately named Shoal Bay. Hung up on the rock, the pirate ship would be a sitting duck for the guns of the British warship.

The pirate captain ordered his men to bring the treasure up from below and load it into the ship’s boat. While they were doing that, he lit a slow burning fuse on a barrel of gunpowder in the magazine. Then he, the first mate, and four crewmen got into the boat and shoved off. No doubt the captain had told the rest of the crew he would be back for them once the treasure was safely ashore. Just as the longboat touched land, the barrel exploded, destroying the vessel and killing every man still on board.

The treasure that the six remaining pirates hauled ashore at Shoal Bay was bound in fourteen packages of gold, silver, and jewels. Each package was so heavy, one man could barely carry it. Once the captain had chosen a site, the four crewmen dug a hole. When it was deep enough, the captain and the first mate lowered the heavy packages to the crewmen waiting at the bottom. When the packages were laid side-by-side at the bottom of the pit, the four men looked up for assistance in climbing out. Instead, they met slashing cold steel. The captain and mate had drawn their cutlasses, and in a swirl of bloody violence, cut the heads off all four crewmen. Now only two people knew where the treasure was, and they had four dead men to guard it.

The captain and the mate filled in the hole and erased all signs of digging. Then they made a map. This map showed the general location of the site, but not the exact spot where the fourteen packages of loot lay buried. That vital bit of information was known only to the captain and the mate. They intended to come back for the swag as soon as they had the means of getting it out of Newfoundland.

The two murderers set off for St. John’s, about ten miles to the north. Bad luck still dogged them. A storm blew in, and they became lost. They wandered in the woods for days before the mate died from exposure. The captain finally staggered into Holyrood on Conception Bay. He was cold, starving, and almost dead. One of the villagers took the stranger in and tried to nurse him back to health, but it was too late.

As the captain lay on his death bed, he told the good Samaritan about the treasure, and gave him the map. The Holyrood man dismissed the pirate’s story as delirious ranting. When the captain died, he gave him a Christian burial, and put the so-called treasure map away in his sea chest.

The Holyrood man eventually left Newfoundland and moved to the United States. Over the years he forgot all about the treasure map tucked away in his sea chest. Only when he was a grandfather did he rediscover it. He showed it to his grandson as he spun fanciful tales of a dying pirate and buried treasure.

When the man died, the map was passed on to his grandson. Now a grown man, he thought that the map might actually be a key to buried treasure. He went to Newfoundland, and found work in the fishery with a Petty Harbour planter. He didn’t want anyone to know that he was searching for treasure, but after a few unsuccessful expeditions to Shoal Bay, he realized that he would need local help.

The young American befriended a St. John’s fisherman named Michael Monahan. He told Monahan his grandfather’s story, and showed him the map. Monahan was well aware of local legends about pirate gold, and believed that the old map was authentic. When the fishing season was over in the autumn, he said, they could get a few adventurous young lads together and go after the Shoal Bay treasure.

The American agreed, but wicked fate struck again. The very next day he suffered a fatal accident: he drowned when he fell through the hatchway of a fish stage! Monahan was saddened by the sudden death of his new friend, but lost no time gaining possession of the map.

When the fishing season was over, Monahan and three friends went to Shoal Bay to search for the treasure. They set up camp, expecting to be there for at least a few days. The very first night, at the stroke of midnight, they were awakened by ghostly voices all around the camp. Monahan crawled out of the tent to see what was going on, but his three friends huddled inside in terror.

Monahan stoked up the campfire and kept it going all night. In the morning, when his friends finally came out of the tent, Monahan told them that ghosts of the dead pirates had come out of the darkness, but the firelight had forced them to stay back. He said they had watched him until they finally disappeared with the light of dawn.

The four young men had had enough of Shoal Bay. They packed up their gear and left, never to return. However, they carried the curse of the pirate treasure with them. Before the year was out, all of them died under mysterious circumstances. What became of the map is not known.

For many years after the Monahan expedition, nobody tried to find the Shoal Bay treasure. Then, in about 1900, a St. John’s man named John Doyle heard the story. He and some friends had planned a fishing trip to Shoal Bay, and decided it would be fun to do a little treasure hunting, too. They set up camp, and after a pleasant evening by the campfire, they retired to their tent.

One of the men had brought along his small dog. It was curled up next to him, sleeping on the tent’s dirt floor. At midnight the men were awakened when the dog suddenly began to bark and whine. It trembled with fear, and dug furiously in the ground. Doyle went to the door of the tent, thinking there might be a bear or wolf prowling around. What he saw caused him to gasp out loud, bringing his friends to the tent door.

It was a dark, moonless night, but out on the water they could see the strange glow of a ghostly, eighteenth-century sailing ship. Fluttering from the mainmast was the Jolly Roger; the black flag of piracy. As the men looked on, unable to believe their eyes, a longboat was lowered over the ship’s side. Six men got into it and began to row for shore. Just as the boat reached the beach, near the very spot where Doyle and his party were camped, the pirate ship suddenly and silently exploded in a mass of flames. For a moment the light lit up the entire bay. Then the ship and the longboat were gone — but that wasn’t the end of the night’s horrors.

Still transfixed, the men watched a sinister-looking black form slither out of the water and up the beach toward them. The dog yelped and whimpered. The men were hypnotized, unable to move. Then the youngest of them, a youth of sixteen, suddenly shouted in terror. He pulled out his camp knife and slashed open the back wall of the tent. This seemed to break whatever spell had held the others. They all fled through that opening, followed by the dog.

The men ran until they reached a barn, where they stayed for the rest of the night. In the morning they returned to their camp. Everything seemed quiet, but they decided there were other places to fish besides Shoal Bay. They packed up their gear and left, abandoning their hopes of finding buried treasure. The Shoal Bay treasure still lies hidden with the bones of the four murdered pirates.

Next to Peter Easton, the most famous pirate in Newfoundland history was Sir Henry Mainwarring. He was an aristocrat and a master seaman who was sent to Newfoundland by the Crown to apprehend Easton and take him back to England in chains. When Mainwarring arrived in Newfoundland, Easton had vanished. Disappointed that he wouldn’t be able to seize Easton’s rich plunder, Mainwarring decided to turn pirate himself and use Newfoundland as his base of operations.

In Notre Dame Bay there is a small isle called Copper Island. It was named when, late in the nineteenth century, a fisherman discovered a hoard of old copper coins there. According to legend, one of the ships in Mainwarring’s pirate fleet was wrecked nearby; the captain of the vessel salvaged the treasure in his hold and buried it on the Island.

People believed that the stash of copper coins was but a small part of the pirate hoard, which was protected by ghostly guardians. Local fishermen usually stayed well away from Copper Island.

However, scary stories were not enough to deter all of the treasure hunters. One day a stranger arrived in the community of Musgrave Harbour, about six miles from Copper Island. He said he was going to find the treasure. He purchased a tent and supplies, hired a boat, and set off for Copper Island.

Several weeks passed, and the stranger did not return. A few local men put aside their fear of the haunted place, and went to look for him. They found his boat on the beach, as well as his camp, well-stocked with supplies, the tent still standing. But there was no sign of the stranger. The men spread out to search the island.

They found him in a pit he had been digging just above the high tide mark on the far side of the island. He was dead, his pick and shovel lying at his side. The corpse bore no signs of violence, but his face was the picture of pure terror. The dead eyes were wide open and bulged from their sockets, as though the last thing they had seen was an object of horror. The searchers concluded that the stranger had died of fright. The ghostly guardians had done their grim duty.

For a long time after that no one ventured out to haunted Copper Island. But eventually a band of treasure hunters found the nerve to go after the pirate loot. Like the unfortunate stranger, this group of young men took a tent, picks and shovels, and enough food for several weeks. When they reached Copper Island, they unwittingly set up camp near the very spot where the stranger had died. Then they began to dig.

No sooner had the treasure hunters’ picks cut into the earth than something extraordinary happened. A tall-masted, square-rigged, old- time sailing ship suddenly appeared out on the water. From the jackstaff flew the ominous black flag of piracy!

The treasure hunters watched, paralyzed by fear, as the ship from a bygone era sailed straight toward them. She slowed to a drift, and they heard the rattle of an anchor chain unwinding. The ship stopped, and moments later a longboat appeared. The men in it were the most vile-looking seadogs imaginable.

At the sight of these phantom pirates, the treasure hunters dropped their tools and bolted. They ran clear across the island to their boat, jumped in, and rowed like madmen for Musgrave Harbour. That was the last time anyone dared to defy the ghosts of Copper Island. Sir Henry Mainwarring’s treasure lies untouched.

We sailed on, we sailed on, till she came in shot,

But still this brave pirate, he dreaded us not;

With voice loud as thunder bold Kelly did say,

“Fire a shot, strike ‘er midships, brave boys, fire away!”And it’s oh, Britons stand true,

Stand to your colours, stand true

We fought them in battle for an hour or more,

Till blood through her scuppers like water did pour;

With balls of good metal we peppered her hull,

Till down came her ensign, staff colours and all.

And it’s oh, Britons stand true,

Stand to your colours, stand true.

These two verses are from a traditional folk ballad called “Kelly the Pirate.” It tells the story of a sea fight between a Royal Navy vessel and a pirate ship commanded by a notorious freebooter named Alphonsus Kelly. In the early seventeenth century, Kelly prowled the waters of Newfoundland preying on merchant vessels and pillaging the fishing fleets of equipment and supplies. According to the stories, Kelly was an Irishman, a red bearded giant who was ferocious in battle and struck fear in all who met him. If a member of his own crew dared to challenge his command, Kelly would break the trouble maker’s back over his knee and toss him to the sharks. Whenever Kelly captured a ship, he took only one man or boy prisoner. This unfortunate would be murdered and then dumped in a hole with a chest full of treasure.

Kelly’s base was an island in Conception Bay that has since been named after him. It covers only five acres and is uninhabited, but Kelly’s Island is said to be the hiding place for his loot, including the gold and silver he seized from treasure ships in the Spanish Main. He allegedly also had a fort on the island. The discovery of an old anchor there is considered hard evidence that pirates had used the island to careen their ships. A huge granite boulder once perched precariously on a cliff above a lagoon that cut into the island’s shore. This rock was a signpost to the treasure sites. Unfortunately for fortune hunters, it fell into the sea long ago.

Alphonsus Kelly was killed in the battle with the Royal Navy. The surviving members of his crew were taken to England where they were tried and hanged. No living soul knew the exact location of Kelly’s treasure, but everyone acquainted with the story knew that the ghosts of Kelly’s victims kept guard over the gold and silver.

Amazingly enough, there are three stories about treasure hunters disregarding superstition and going after the loot. In the middle of the nineteenth century, a Newfoundland fishing captain came into possession of a map that showed the location of a treasure site on Kelly’s Island, and found some old gold coins. In 1901, a stranger asked a local fisherman to take him out to the island. The fisherman waited in the boat while the stranger went ashore. When the stranger returned, he was carrying an old ship’s boiler. People later said that the boiler probably contained loot that the stranger didn’t want the fisherman to see. Then, in the 1930s, another stranger supposedly found some old coins on the island.

But even if these stories are true, they account for only a small percentage of the treasure that Kelly the pirate supposedly buried on his island. The bulk of the gold and silver is still there. And so, says local legend, are the ghosts of Kelly’s victims.

The Ghosts of Chapel Cove Pond

Tales of treasure and ghosts at Chapel Cove, on the east side of Holyrood Bay, go back to the early eighteenth century, when the area was first settled. Legend says that some local men found a stranger, an old sailor, near death beside Chapel Cove Pond. The dying man told them that pirate treasure was buried nearby. With his final breath he warned them of a terrible curse that would fall upon anyone who tried to get their hands on it.

The men buried the stranger and then, foolishly ignoring the warning, they began to dig for the treasure. They found a strongbox, but were struck dead before they could lift it out of the hole. Presumably, whatever dark force was protecting the treasure covered it up again.

Over the years, other fortune hunters searched for the hidden riches. They always gave up the quest abruptly, and wouldn’t say why. Stories circulated about ghost ships and headless phantom pirates.

One Chapel Cove man decided that he would be safe from malignant spirits if he first armoured himself with the protection of the Church. He went to his parish priest and received a blessing that the good father said would ward off evil. In return, the man promised to give the priest a portion of the treasure, for the benefit of the parish’s widows and orphans.

The treasure hunter’s partner was an old Irishman who was well versed in supernatural lore, and supposedly knew how to deal with spirits. To keep their work secret, they waited for a moonless night, put some picks and shovels in a cart, and set out for Chapel Cove Pond.

As they made their way along the shore of the pond, they suddenly saw a strange light out on the water. Before their disbelieving eyes, the light took the shape of an old sailing ship. Most unnerving of all, the phantom ship was moving along with them as they followed the shoreline.

The sight of the ghost ship greatly frightened the old Irishman. He didn’t want to go on. But his partner had faith in the protective blessing he’d received from the priest, and persuaded the nervous old fellow to continue.

They reached their destination at the head of the pond, the place where the dying old sailor had been found years earlier. They hauled their tools out of the cart and began to dig, casting frequent, jittery glances over their shoulders at the ghost ship, which now sat motionless and silent on the water.

The treasure hunter and the Irishman had to dig deep before, at last, they heard the clang of a pick striking an iron box. In their excitement over the prospect of wealth right at their fingertips, they momentarily forgot about the treasure’s guardians. They frantically dug away the earth from around the box, and with great exertion pulled it out of the hole.

The two giddy men prepared to lift the heavy box onto the cart. Only then did they suddenly realize that they were not alone. Standing just a few feet away from them was a figure that made their hair stand on end.

The apparition was a huge man with a big red beard, wearing the unmistakable clothing of a sixteenth-century pirate captain. Behind this fearsome figure were two more apparitions: headless pirates with cutlasses in their hands.

The poor, old Irishman, no expert on spirits after all, fainted and fell into the cart. The treasure hunter from Chapel Cove was made of sterner stuff, and besides, he had that protective blessing. No mere fiend from hell was going to stand between him and his dream of fabulous wealth. With a defiant glare at the ghosts, he heaved with all his strength to lift the treasure chest onto the cart. He would take the gold and the unconscious Irishman home, and the ghosts could go back to whatever netherworld they had come from.

But defying dark powers isn’t that easy. The red-bearded ghost pirate lashed out and struck the man down with a single blow. While the man was helpless on the ground, the headless ghost pirates came at him with their cutlasses raised. It seemed as though the man was about to lose his own head, but he did not cringe or cower.

With the swords poised to behead him, the man cried out that he had the blessing of the Church. He said he had promised to give a share of the treasure to a priest to help the needy. What use was the gold, he demanded to know, to men who were already dead!

The red-bearded giant then let out such a howl of rage that the man fainted from pure fright. When he regained consciousness, he was lying in the cart next to the Irishman. The blessing had apparently protected his life, but it had not guaranteed that he would get the gold. He looked out at the water, and saw the red-bearded pirate and his headless accomplices returning to their ship in a longboat. They had the treasure chest with them. When they boarded the ship, it disappeared in a wink. The man fell on his knees and gave thanks that he was still alive. He swore on the spot that his treasure hunting days were over.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, some of the most notorious pirates in the annals of the sea visited Newfoundland’s shores, including Bartholomew “Black Bart” Roberts and bloodthirsty Edward Low. If there is truth to any of the legends, the man whose name practically became synonymous with the word pirate; William Kidd, also came to Newfoundland. Furthermore, say the legends, he left treasure there.

In reality, William Kidd wasn’t much of a pirate. He was a respected, middle-aged English sea captain who, in 1695, was commissioned by the Crown to hunt down pirates and attack any ships sailing for France, >England’s principal enemy. For two years Kidd roamed the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, and the Red Sea, in his ship the Adventure Galley. He did not capture a single prize.

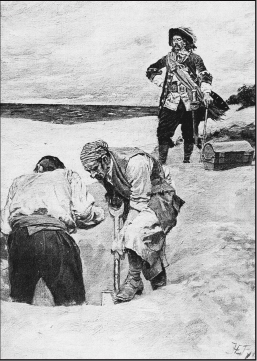

The notorious Captain Kidd looks on as his men bury a treasure chest in this 1894 illustration by Howard Pyle. According to legend, pirate captains buried dead men with their treasure, so their ghosts would guard it.

Pressured by a mutinous crew, Kidd seized four merchant vessels, which he claimed were sailing under the French flag, and sold their cargoes ashore. This only whetted his men’s appetite for more plunder. Their next prize was the one that would make Kidd’s name as a pirate.

In January 1698, Kidd captured the Quedah Merchant, an Indian ship that Kidd claimed was sailing under French authority. This ship was the kind of prize every pirate dreamed of: she was loaded with gold, silver, jewels, and silk — enough loot to make every man aboard the Adventure Galley rich.

Unfortunately for Kidd, word of his exploits reached England, and he was declared a pirate, with a price on his head. When Kidd eventually reached the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean, he learned, much to his surprise, that he was a wanted man. He decided that he would return home and clear his name. He made a stop in Boston in July 1699, and was promptly arrested.

Kidd was sent back to England in irons, where he languished in prison for two years before he finally went to trial. The press had already painted him as the most black-hearted villain that ever trod a deck. The trial was a sham. Kidd was found guilty and condemned. He was hanged on May 23, 1701, and his body was gibbeted.

But what happened to all that plunder? Captain Kidd was one of the few pirates known to have actually buried treasure. Shortly after his arrest, authorities found a cache he had buried on Gardiner’s Island at the eastern tip of Long Island, New York. They dug up 1,111 ounces of gold, 2,353 ounces of silver, and more than a pound of precious stones. A few years later two former members of Kidd’s crew bribed their way out of prison and went straight to a place on the coast of Pennsylvania where they recovered a cache of gold worth 2,300 English pounds sterling.

Rumours abounded that there were more hidden caches of treasure: but where had Kidd hidden it? No one can say for certain just where Captain Kidd went between the time he left the Indian Ocean on a ship weighed down with treasure, and the day he arrived in Boston. Fortune hunters have looked for Kidd’s lost treasure in the Dominican Republic, the eastern states of the U.S., New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and of course, Newfoundland.

Bennett’s Grove, on the south side of Quidi Vidi Lake in St. John’s is reputed to be the site where Captain Kidd buried five kegs of gold. The loot is supposedly in an unnamed gully that is protected by pirate ghosts. These unsavoury spirits confront anyone who goes near the place, whether they are treasure hunters or not. There is even a story that early in the twentieth century, some American adventurers found some of the gold and smuggled it off the island.

Ferryland, which has connections with pirates dating back to the days of Peter Easton, is also said to be a Kidd treasure site. Many people have allegedly claimed to have seen a ghostly pirate ship on the water there. One story even tells about a twentieth-century Ferryland resident finding a gold ring studded with diamonds. Was the ring part of Captain Kidd’s treasure? If so, do pirate ghosts still watch over the hoard?