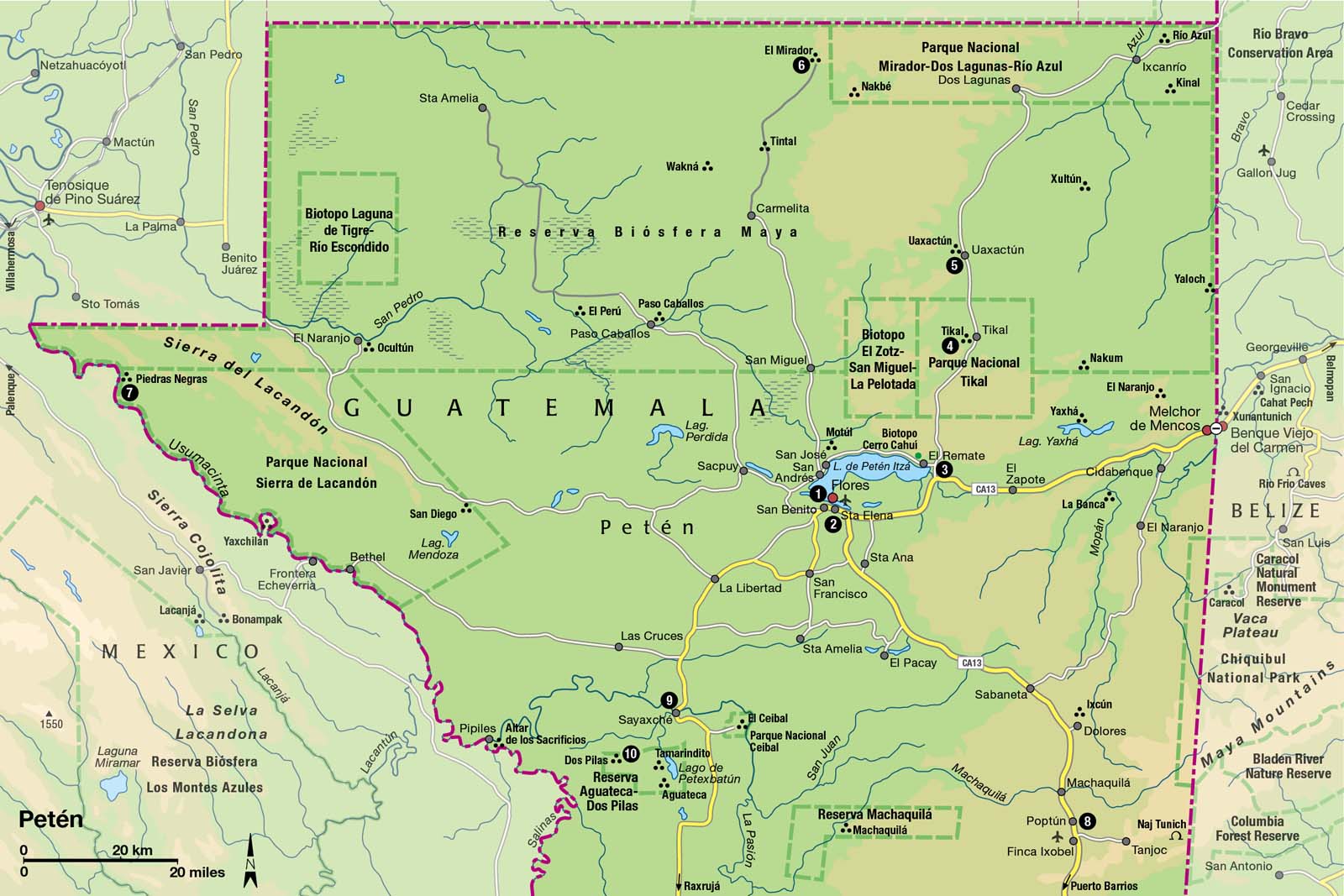

Petén

Hidden in this vast northern jungle department are some of the most spectacular Maya cities, including the indisputable, dazzling jewel in their crown: Tikal.

Main Attractions

Between 750 BC and around AD 900, arguably the greatest of all pre-Columbian cultures, the Maya civilization, evolved, excelled, and ultimately collapsed in the lowland subtropical forests of what is now northern Guatemala. It was in the jungles and savannas of the department of Petén, which covers a third of the country, that the Maya city-states succeeded in creating some of the greatest human advances in the continent: a precise calendrical system, pioneering astronomy, a complex writing system, breathtaking artistry, and towering architectural triumphs.

There’s compelling evidence that a combination of environmental and social factors (including overpopulation, warfare, and revolt) prompted the disaster of the Maya collapse, but the exact reasons are still subject to animated academic debate. Whatever the truth, the jungle reclaimed the temples, plazas, and palaces, so that by the time the 19th-century explorers arrived, buildings were choked with over 1,000 years of forest growth.

Penetrating the Petén

The Spanish all but ignored the area until, in 1697, they finally defeated the tiny isolated Itzá Maya tribe that lived on the shores of Lago de Petén Itzá. Most of the entire department of Petén was all but inaccessible until the 1960s, when the hellish trails that sneaked through the trees between the capital and Flores were upgraded to dirt roads. At this time, most of Petén was still covered in pristine forest, with only a few thousand human inhabitants. Government schemes opened up the forests to land-hungry settlers, loggers, and oil prospectors, and the population spiraled (now estimated to be over 500,000). As much as 50 percent of the forest may have already been cut, with destructive “slash and burn” farming and logging, at first clearing the trees, then moving on and leaving the degraded land to cattle ranchers.

View from Temple IV at Tikal, whose ruins are swathed in jungle.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The Petén is still Guatemala’s wild frontier province, and transportation, communications, hotels, and restaurants are generally pretty basic away from the main town of Flores. To get to Maya sites like El Mirador takes time (unless you take a heli-tour!), planning, and local expertise – there are a number of excellent local organizations that operate expeditions to the remote ruins. The Petén climate is perennially hot and humid. The rainy season can extend until December, and can disrupt overland travel to isolated areas. Tikal and Flores are always accessible nevertheless.

Scarlet macaws can be seen around Petén.

Corrie Wingate

Petén’s Wildlife

Despite illegal logging and environmental damage, vast areas of the Petén forest remain intact, and this is still one of the best places in Central America to see some spectacular wildlife. A number of national parks and reserves have been established (and combined as the Maya Biosphere Reserve) to protect the subtropical habitat of over 4,000 plant species and animals that include jaguars, crocodiles, tapirs, ocelots, collared peccaries, armadillos, boa constrictors, blue morpho butterflies, and 450 resident and migratory birds. Even if you only make it to Tikal, you should hear the deafening roar of the howler monkey, glimpse toucans and parrots squabbling in the forest canopy, and perhaps spot an ocellated turkey or a gray fox in the undergrowth .

Flores

Set on a natural island in Lago de Petén Itzá, connected via a small causeway to shore, Flores 1 [map] (population 7,000) is a peaceful, civilized place now largely dependent on tourism. It is a small, tranquil, and historic town that’s by far the most pleasant urban center in the department. Today’s town stands on the remains of the old Itzá Maya capital, Tayasal, which was first visited by Hernán Cortés in 1525, left alone, and only conquered in 1697. The Spanish had no appetite for jungle life, and Flores retained closer contact with Belize and Mexico until the road links to the rest of Guatemala improved in the late 20th century.

The tropical flower heliconia.

Corrie Wingate

The best way to explore Flores is to stroll around the lane that circumscribes the shoreline – it will take you about 15 minutes to walk around the cobbled streets and lanes of the town. Some of its architecture is delightful: the older houses are brightly painted wooden and adobe constructions, many of the hotels have been painted in harmonious pastel shades, and there’s a fine plaza in the center of town that boasts a twin-domed cathedral.

Just across the causeway, the ugly urban sprawl of Santa Elena 2 [map] and San Benito (combined population 72,000) could not present more of a contrast. These are rough and ready frontier towns, typical of a region where laws can be ignored and the authorities bribed if necessary. Development is ramshackle, and the streets are thick with dust and dirt. There’s no reason to be here except to visit a bank (there are a couple in Flores anyway) or catch a bus out of town.

TIP

Boat trips are available from Flores to the surrounding sights, including traditional villages such as San José and San Andrés, the ARCAS wildlife rescue center next to the zoo, ruins, and Aktun Kan caves.

Around Flores

On the banks of Lago de Petén Itzá, around Flores, there’s a number of things to see, most of which are best visited by boat – you will find boatmen by the Hotel Santana and on the Santa Elena side of the causeway. The Petencito zoo (daily 8am–5pm; charge) and a lookout point on a small island are the most popular destinations, but if you want to to see a traditional Petén village, head for San Andrés on the north shore. The neighboring village of San José, 2km (1.2 miles) away, is another friendly place, where efforts are being made to preserve the Itzá Maya language. Some 4km (2.5 miles) beyond San José are the minor ruins of Motúl, where there are some small pyramids and a stela to see.

Some 2km (1.2 miles) south of Santa Elena, the caves of Aktun Kan have some bizarre formations that vaguely resemble animals, plus plenty of stalactites, stalagmites, and the odd bat.

The small but spread-out village of El Remate 3 [map] is another good base for exploring Tikal, with a burgeoning number of hotels. It is 30km (18.5 miles) from Santa Elena/Flores and particularly convenient if you are approaching the ruins from Belize.

About 3km (2 miles) from the center of the village is a small nature reserve, the Biotopo Cerro Cahuí (6.30am–dusk; charge). The reserve is home to a remarkable diversity of plant life (mahogany, ceiba, and sapodilla trees, orchids and epiphytes), animals (spider and howler monkeys, armadillos, and ocelots) and particularly an exceptional quantity of birds, with hundreds of species recorded here.

it’s a steep climb to the top of Temple II at Tikal.

Corrie Wingate

Tikal

Entombed in dense jungle, where the inanimate air is periodically shattered by the roars of howler monkeys, the phenomenal, towering ruins of Tikal 4 [map] are one of the wonders of the Americas. Five magnificent temple-pyramids soar above the forest canopy, finely carved stelae and altars in the plaza eulogize the city’s glorious history, giant stucco masks adorn monuments, and stone-flagged causeways lead toward other ruined cities lying even deeper in the jungle.

The pretty town of Flores, on Lake Petén Itzá.

Corrie Wingate

Tikal’s scale is awesome. In the Classic period its population grew to almost 100,000. Trade routes connected the city with Teotihuacán (near modern-day Mexico City), the Caribbean and Pacific coasts. Temple IV was built to a height of around 65 meters (213ft), complete with its enormous roof comb. Exquisite jade masks, ceramics, jewelry, and sculptures were created. There were ball courts, sweat baths, colorfully painted royal palaces, and another 4,000 buildings to house the artisans, astrologers, farmers, and warriors of the greatest city of the Classic Maya civilization.

FACT

After the death of a Maya ruler, the stelae describing his life were often broken up and placed in his tomb, as they were considered personal records rather than public monuments.

Most travelers concur that Tikal is the most visually sensational of all the Maya sites. To get the most out of your visit, try to stay overnight at one of the three hotels close to the ruins, to witness the electric atmosphere at dawn and dusk when the calls of toucans, frogs, monkeys, and other mammals echo around the surrounding jungle. The temperature and humidity are punishing at any time of year, so make sure you take plenty of water, and also insect repellent.

History

Tikal is one of the oldest Maya sites: only some of the Mirador Basin sites and Cuello (in Belize) predate it. It’s located in the central lowland Maya zone, the cradle of Maya civilization, in a dense subtropical forest environment. The earliest evidence of human habitation at Tikal is around 700 BC, in the Preclassic period. By 500 BC the first simple structures were constructed, but Tikal would have been little more than a small village at this time and Nakbé, some 55km (34 miles) to the north, was the dominant power in the region.

By the time Tikal’s first substantial ceremonial structures were built (the North Acropolis and the Great Pyramid) about 200 BC, powerful new cities had emerged, above all the enormous El Mirador, 64km (40 miles) to the north and connected by a sacbé raised causeway.

By the start of the Classic period in AD 250, El Mirador and Nakbé had faded and Tikal had grown to be one of the most important Maya cities, along with Uaxactún. The great Tikal leader Great Jaguar Paw and his general Smoking Frog defeated Uaxactún in AD 376, bringing on an era when Tikal and rival “superpower” Calakmul contested dominance of the Maya region for another two centuries. Huge advances were made in the study of astronomy, calendrics, and arithmetics under Stormy Sky (AD 426–57). But disaster struck in 562 when upstart Caracol (in Belize) defeated Double Bird of Tikal and forged a crucial alliance with Calakmul that was to humble Tikal for 120 years – no stelae at all were carved in this time.

TIP

Your entry ticket into the ruins at Tikal is officially only valid for one day, but if you enter the site after dusk, your ticket will automatically be stamped for the following day, allowing you another full day to explore at no extra cost.

Tikal’s renaissance was sparked by Ah Cacau or Lord Chocolate (682–734) and continued by his son Caan Chac, who ordered the construction of most of the temples that bestride the ruins today, which are taller and grander than earlier buildings. Caan Chac also reassumed control of the core Maya area, eclipsing bitter rival Calakmul. Tikal continued to control the region, enjoying unsurpassed stability and prosperity into the 9th century; it faded quickly by AD 900, however, along with all the other lowland sites.

View from Temple V at Tikal.

Corrie Wingate

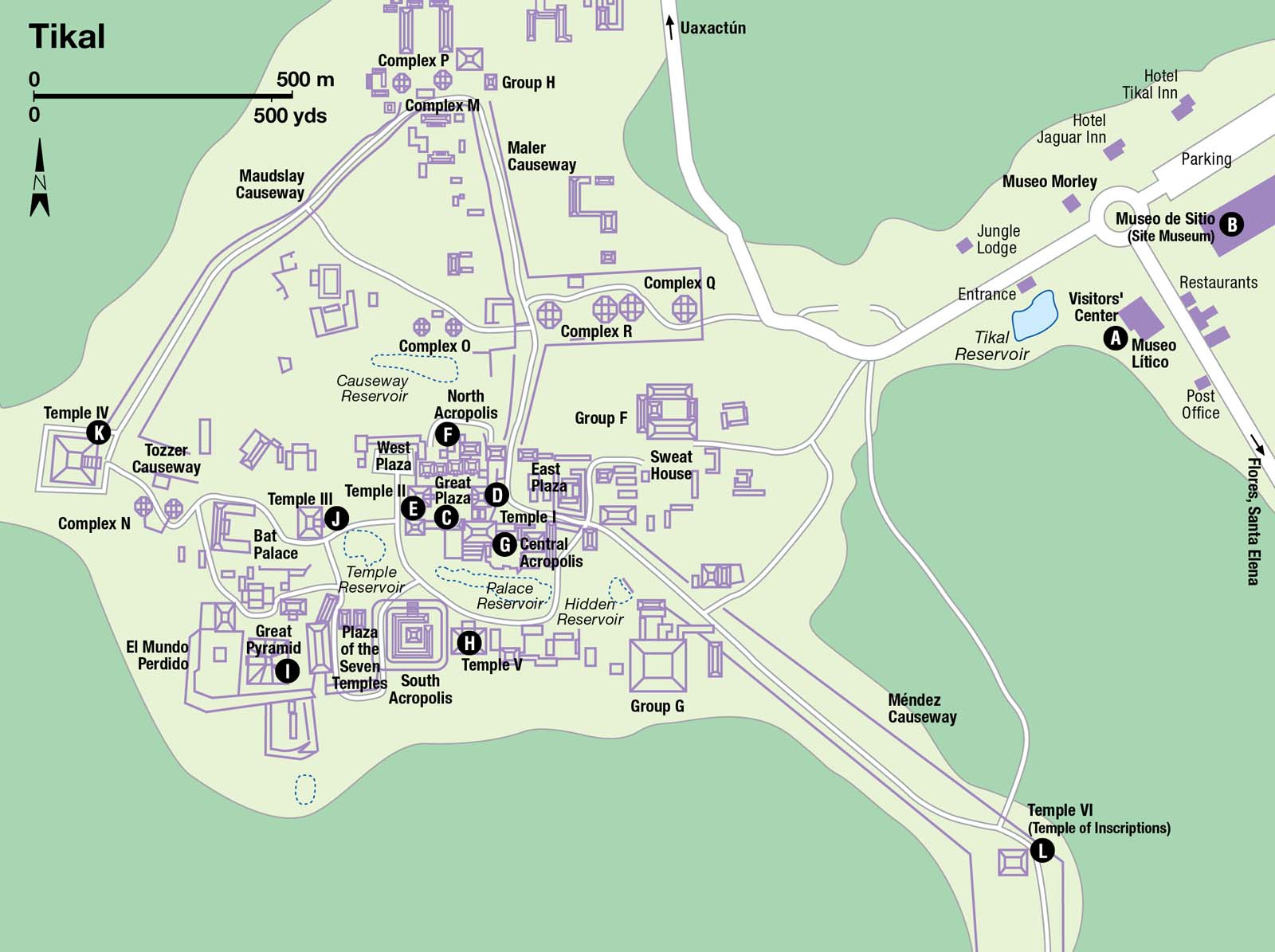

The site

Before (or after) you enter the site, have a look in the Visitors’ Center A [map], where the Museo Lítico has an excellent collection of stelae and carvings; opposite is the Museo Morley, where the exhibits include ceramics, jade, the burial ornaments of Lord Chocolate, and Stela 29, the oldest found at Tikal (both museums are open daily; charge). Nearing completion at the time of research, Tikal’s impressive new Site Museum, Museo de Sitio B [map] promises a state-of-the-art setting for a stunning collection of artifacts and relics gathered from the ruins, with lots of interactive displays.

The Great Plaza C [map] is the first place to head for, the nerve center of the city for 1,500 years. The grassy plaza is framed by the perfectly proportioned Temples I and II to the east and west, the North Acropolis, and the Central Acropolis to the south. In Classic Maya days, these monumental limestone buildings would have been painted vivid colors, predominantly red, with clouds of incense smoke smoldering from the upper platforms. Civic and religious ceremonies, frequently including human sacrifice, would have been directed by priests and kings from the top of the temples.

Temple I D [map] (also known as the Temple of the Giant Jaguar because of a jaguar carved in its door lintel), was built to honor Lord Chocolate, who was buried in a tomb beneath the 44-meter (144ft) high structure with a stately collection of goods (now exhibited in the Morley Museum). Three small rooms on top of the temple were probably the preserve of priests and kings, adorned with beautifully carved zapote wood beams and lintels. Facing Temple I across the plaza is Temple II E [map] (also known as the Temple of the Masks), slightly smaller at 38 meters (125ft) tall, and a little less visually impressive, too, because part of its massive roof comb is missing. Both temples were constructed around AD 740.

Between the two mighty edifices, on the north side of the plaza is a twin row of stelae and altars, about 60 in all. Many date from Classic Maya times, but were moved here from other parts of the site by post-Classic people in a revivalist effort – Stela 5 has some particularly fine glyphs. Behind the stelae is the untidy bulk of the North Acropolis F [map], a jumble of disparate masonry composed of some 16 temples and an estimated 100 buildings buried underneath, parts of which are some of the oldest constructions at Tikal, dating back to 250 BC. Most of the temple structures are late Classic, and missing elaborate roof combs, but all are built over much earlier foundations. Among the remains are two colossal Preclassic stucco masks.

On the south side of the plaza is the Central Acropolis G [map], a maze of buildings thought to function as the rulers’ palace, grouped around six small courtyards. In front of the Central Acropolis is a small ball court, and behind it to the south is the palace reservoir and the restored 58-meter (190ft) Temple V H [map]. A very steep staircase ascends this temple (which may be closed following heavy rain), and from its summit there’s an astonishing view of the entire site.

Temple II – the temples sit in clearings in thick jungle.

Corrie Wingate

The Lost World

Reached by a trail from Temple V, El Mundo Perdido (The Lost World) is a beautiful, atmospheric complex of buildings, dominated by the mighty Great Pyramid I [map], a 32-meter (105ft) high Preclassic monument that’s Tikal’s oldest known structure. It is also an ideal base from which to watch sunrise or sunset. Temple III J [map], north from here, peaks at 55 meters (180ft) and remains cloaked in jungle, while Temple IV K [map] has been half-cleared of vegetation. Temple IV is the tallest of all Tikal’s monuments, at around 64 meters (210ft), or 70 meters (230ft) if you include its platform, making it the second-highest pre-Columbian structure ever built – only the Danta temple at El Mirador eclipses it. Getting to the top involves a tricky climb up a ladder, but the view from the summit really is astounding – mile after mile of rainforest, broken only by the roof combs of the other temples.

FACT

One of the buildings at Uaxactún, the unimaginatively named E-VII in Group E, functioned as an observatory in Preclassic Maya times (one of the first ever built) and was built to align with the sunrise on the summer and winter solstices.

There are thousands of other structures to explore – some considerable like Temple VI, also known as the Temple of Inscriptions L [map], down the Méndez causeway leading from Temple I, with its 12-meter (39ft) high roof comb and intricate glyphs – most much more modest, the homes of the workers and farmers. Take a good map and great care if you go for a walk in the forest; people get lost every year.

Mayan vase, dating from AD 900, found in ruins at Uaxactún.

The Granger Collection, NYC / TopFoto

The northern ruins

In the thick jungle of the Maya Biosphere Reserve in the extreme north of Guatemala, there are dozens more Maya ruins, most almost completely unexcavated. The easiest to get to is Uaxactún 5 [map], 24km (15 miles) away, and connected to Tikal by a dirt road, served by one daily bus from Flores/Santa Elena. If you can, visit Uaxactún before Tikal because the ruins are much smaller. Uaxactún rivaled Tikal for many years in the early Classic era, but was finally defeated in a battle on January 16, AD 378. Today there is an interesting observatory comprising three temples built side by side (Group E), numerous fine stelae, simple accommodation, and, of course, the jungle to explore and admire.

Just a couple of kilometers from the Mexican border, the Preclassic metropolis of El Mirador 6 [map] matches Tikal in scale and may yet be found to exceed it. Unless you take a pricey helicopter tour, it is only accessible by foot. Other remote ruins, including Nakbé and Río Azul, right on the tripartite border where Belize, Mexico, and Guatemala meet, can also be found here .

Finally, way over on the other side of the Maya Biosphere Reserve on the Río Usumacinta is the extremely isolated Piedras Negras 7 [map]. The site, which towers over the Guatemalan bank of the river, can only be accessed by boat, with trips organized in Guatemala City (see Travel Tips). Some of the finest stelae in the Maya world were carved at Piedras Negras, and there is a megalithic stairway and substantial ruins to admire, including a sweat bath and an impressive acropolis, with extensive rooms and courtyards.

South and east of Flores

Two roads creep through the jungle south of Flores, the busier of which heads past Poptún 8 [map], a dusty, featureless town 113km (70 miles) away, where a fine ranch makes an idyllic place to stay. At the American-owned Finca Ixobel, a short distance out of town, there are many opportunities to explore the region’s cave and river systems and enjoy great company, while the home-cooked food is delicious.

Taking the other route south, 62km (38 miles) from Flores is the town of Sayaxché 9 [map], a frontier settlement by the Río de la Pasión. This is an ideal base to visit the ruins of El Ceibal, set in a patch of rainforest 17km (10.5 miles) away, which was a large city dating from Preclassic times. Much remains unreconstructed, but there’s a fine plaza and stelae, an astronomy platform, and many noisy howler monkeys. South of Sayaxché is the lovely, forest-fringed Lago de Petexbatún, with three interesting ruins close by. Aguateca is the most accessible, positioned high above the lake; the partly restored ruins are scattered around a natural chasm. Dos Pilas ) [map] is a bigger site with some fine altars, a ball court, and four short hieroglyphic stairways.

Finally, 73km (45 miles) east of Flores are the substantial ruins of Yaxhá, which are steadily being restored. Structure 216, which tops 30 meters (98ft), is Yaxhá’s most impressive construction. There’s also a fine Preclassic temple cluster, with three large pyramids arranged in a triadic formation, and two giant stucco masks.