IDEAS BOOK P. 18:

It can’t just be about rescuing a damsel in distress because it’s an indie game and indie hipsters will give us hell and for good… Anyway, the hero has to have shitty powers… Something limited, the ability to only fight in water, but he can’t be as restricted as Aquaman because he still has a speck of self-respect. It’s a PLATFORMER and he’s collecting family heirlooms: a pearl, goldfish statues, purple coral shards and meteorite crystals shaped like people. At the end of the first stage, after killing an eel with a posh accent, you learn that the King of Tides (a crab with an eye patch) needs all these trophies too, in order to use their magical powers to send off waves across the world and let water take over forever so he can teach people a lesson about the power of nature (remember to make the game box fully recyclable to really hit it off with that demographic). But you, the hero, you steal it all anyway with the help of a telepathic guide, Mona, who reveals to you that she’s been trapped for thousands of years in an underwater volcano (which you will find at the end of a level). But then, suddenly, when you finish collecting everything, the world just dries up, and now freed from the crushing ocean, Mona can save herself. Once she sees the state of the world above, she turns against you because it’s your fault, it’s your fault and you did this. Why did you not say anything? Did you not see the signs? She would have preferred another thousand… But then you realise that you could only understand her telepathically, and you’ve no fucking clue what she’s actually saying now that she’s free. The King of Tides just shrugs when she speaks, a crabby shrug, and it doesn’t help you that she only speaks French, and she then beats the shit out of you to bring back oceanic life as we know it.

Though sometimes the plot isn’t the problem. The issue here will be getting Jaime to correctly calibrate all the underwater physics and their complicated particle effects.

• • •

At the metro he takes the line 1 from Manuel Montt to Baquedano. It’s only two stops away but he didn’t sleep and so he’s too tired to walk. He’s always found it surprising how tired he is and how little weight he puts on even when he sleeps well. And he never even exercises and eats all that trash. It might be genetic and all, but it’s probably his body working overtime to save him the embarrassment of asking for metro space on his way to work. Can positive things also be psychosomatic? Anyway, he likes rush hours in the metro. He’s standing by the metal pole in front of the door which he can’t even see because of all the people.

He’s touching shoulders with this real fat guy who’s sweating and reading the La Cuarta newspaper, some article about an American model called Jerry-Springs and why her liberal parents called her that, all in a tiny black bikini and smileys on the nipples and CAPITAL LETTERS EVERYWHERE and hashtags EVERYWHERE on the page because it’s so #important and the guy keeps sweeping the gelled-up black remains of what his hair used to be to one side with the other hand as if it made a #fuckingdifference. To Tomás’s left is a woman with big headphones on and she’s carrying a cardboard tube in her backpack. She must be an architecture student because she smells of glue, doesn’t look like a tramp (has shoes) and has small cuts on her fingers that end in yellow and red polka dot nails. She bites them and the colours have all cracked. He wonders what would happen if he tapped some random woman’s shoulder like hers and asked her a deep question about herself, like, ‘don’t you think you’ve dealt with enough?’ or something more specific to her, ‘do you love symmetry?’ or some vague bullshit that only hippies with BAs would answer. He likes to think about this sort of thing because he feels capable of anything, of making people take their headphones off out of awe because he’d have broken the unspoken rule about never speaking to someone you don’t know in the metro and… Although really, he just likes it because he knows he would never do it and he’d like someone else to do it to him. But what would they ask him?

He could have studied something useful too, and by that he means essential, unlike videogames design, unlike narrative, unlike coffee, unlike pizza, unlike hobs and bed frames and ceramic plates and cups of any kind. He often asks himself what he could have done instead, but he always just ends up making characters, other people in a Tomás disguise that they don’t even want, didn’t even choose. Sometimes it’s a doctor in a warzone curing people of terrible diseases in a cliché of poverty, stray dogs and limbless kids everywhere, a country called Republic of Developing. But then he comes from that Third World too, which makes the whole thing confusing. Other times he’s a banker who’s depressed because his working-class friends deleted him from Facebook when he bought pet passports and a yacht he ironically called The Winner. Whoever it is, it’s never just Tomás. Eva used to say people were always hoping their lives would change, which she thought was pretty fucking stupid because change, she said, is just a nicer word for loss.

Today, like most days, he’s just Tomás, and he’s taking the same metro he’s taken since he was eighteen and he doesn’t recognise any faces, no one, not even his own on the glass doors that shake and pound to echoes in tunnels where no one’s been and so he can’t lose a thing. He reads the edge of the student’s cardboard tube as she leaves and he’s sure it says ‘Flat: cream-coloured’.

More people get on. The doors close and everyone stops talking and it’s just a long buzz, the metal scratching, sometimes even giving out sparks that briefly light the wiring on the walls of the tunnel. A guy in a suit presses against him and Tomás sees him from the reflection in the window. The guy takes out small scissors from his jacket’s inside pocket and starts trimming his moustache on the sides and above the lips. Some of the hairs land on the back of an old lady’s neck and on Tomás’s shoes and they just stay there. He’s surprised that inside a tunnel with all this noise and the trembling of the metro there can be no wind at all. No one talks but everyone’s touching someone, staring at someone, and Tomás swears this is as close as anyone gets to anybody else in Santiago and why would anyone prefer to walk? The metro lines are all so small and the wait between stations is never more than a minute or two. Eva once said that in Paris the metro was like a spider web and that rush hours over there are hell on Earth, but he finds that hard to believe because she also said instant coffee and hot dogs were hell on Earth. Still, he could have just agreed with her.

Baquedano station. It’s a short walk to Bellavista from here but even if he knew where she lived (she said it was better for him not to know), he wouldn’t know what to tell her. He could pretend to be one of those American Jehovah’s witnesses that plague Santiago and knock on every door until he finds her, but he doubts she’d be impressed by what she’d witness. She’d probably let out a small laugh and say that she knew it, that she knew that what he had was in some way a crisis of faith, but that yet again, he went about it the wrong way, and she would then add that there are deities much more powerful than Jesus… And what do people say to their exes? He has a full page of it. His IDEAS book, written upside down from the last page (page 100), says:

God, he hates that word: EX. It makes people sound like an exam mistake or an illegal trespassing signpost. Whoever invented it must have lived in Santiago too.

He gets out of the crowd in the metro station and walks to the Fuente de Soda nearest to him to get a takeaway coffee and a fried sopaipilla. It comes wrapped in a blue paper napkin that’s definitely toilet paper and it’s covered in grease stains and mini eruptions of oil now brown from all the use. He sits on the bench facing Yiyo’s shop and writes his name on it where it now says ‘Lolita Diaz’. He smiles and stretches his legs until well after the yawn has passed. He takes one bite off the sopaipilla and he feels full, and all the pigeons in the world start to crowd at his feet because they know it. Eva used to say pigeons were dirtier than rats and should be killed. He told her: if they exist, they must be important. But when you see them crowding around you with all their fucked up feet and necks breaking this way and that with that throaty blipblipblupping and skipping to get your crumbs that they confuse with cigarette buds, convinced of their invisibility and entitled to everything you own at restaurant terraces… You have to wonder if anyone would miss them if they ever returned to their own planets. He should have just agreed with her, the useless pigeons, their useless flights from roof to wire to roof, the useless noise and useless conversations. ‘Pigeons are the wisdom teeth of the Earth, useful only to a world without people.’ It didn’t make any sense but that’s what she had said once when they passed out drunk next to the canary cages in Yiyo’s garden, where he’d also taken in orphan pigeons. He throws the rest of the sopaipilla at the birds that pick on it before disappearing to the street corner where they sell paintings of poets no one recognises.

Yiyo’s music shop hasn’t opened yet. It’s called AudioPop. The shutters are only halfway up. Tomás takes out his IDEAS book and writes,

Dear Eva,

Thank you for your letter. I loved the colourful spots. We are getting older. Isn’t that funny? And since we aren’t being spared the time, I think we should meet up and talk it all over. Again, thank you for the card. The colour choice was fantastic.

Love,

Tomás x

PS. I have foie gras at home. I now get what you meant about subtlety.

He tears out the page and puts it in a used gas bill envelope because he has to make sure she reads it. He takes out a roll of sellotape from his bag and seals it.

He looks up at the shop and waits for Yiyo to open. He wishes he were selling drum kits and guitars too. Yiyo used to offer him work here when they were younger but Tomás just laughed it off. He always said he was working on the new thing and that this time it’d be huge. And the truth is that before the breakup, before his last game came out, he really did believe it’d be huge, he’d be HUGE. He used to take notes of the smallest details so he could then include them in his games: when the smog gets bad, everyone in Santiago has dust halos in the sun; the neighbour’s dog barks in perfect jazz straight eighths; Eva’s fake painting-poster on their wall is called Sky but the downward strokes, the blue waves and their unfinished circles that cross over buildings and people, suggests it just didn’t know it was an ocean. By the time they split up, Eva didn’t want to hear a word about his stories. She even declared herself ANTI-NARRATIVE one night, as if by his doing she’d lost all hope of ever loving any story, any story at all. ‘It’s the sky,’ she said, ‘that’s what it is and that’s what it’s called, even if now that you said otherwise we can never see it again. And the yellow silhouettes nose-diving into the edge of the frame, those are all birds.’

He sees Yiyo inside the shop coming to open and waves at him. He doesn’t see Tomás at first but when he gets to the door he waves back. Tomás stands but Yiyo signals him to wait for him to roll up the shutter. He comes out wearing a Sonic Youth T-shirt under a red and black flannel shirt and black jeans, like a cheap barista.

‘Hey dude, how’s it going?’ Tomás says.

‘It’s too early to say. Same as always I guess, man, you?’

‘Same really.’

‘Actually dude, I’m pretty excited,’ Yiyo says rubbing his face with one hand. ‘We’re recording the guitars for Fármacos tonight. I’m really nervous.’ He waves to some guy opening a hat shop behind Tomás.

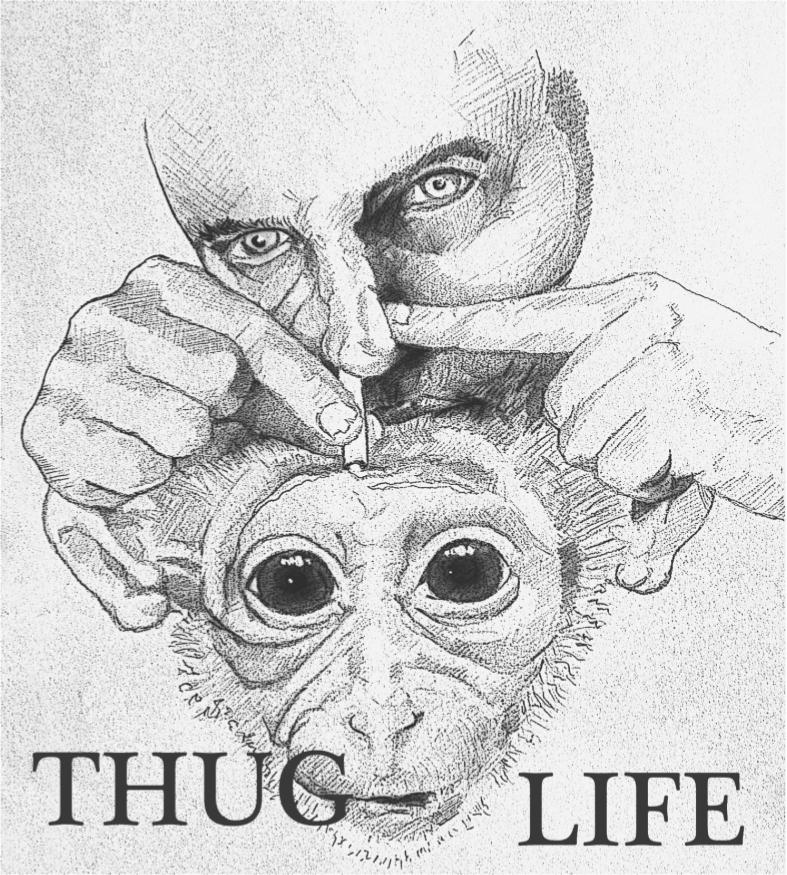

Fármacos is the band Tomás would be in if he hadn’t been so persistent in getting a real job, which is just C++LIFE code for <Function Name='LACKING IMAGINATION'/>. He’d always had better grades than Yiyo through school, even without studying, and Yiyo just took a gap year to play music and travel without any money or anything all the way from Brazil, across the Colombian jungle and into Panama, walking and hitching rides in boats filled with monkeys, underage prostitutes and cocaine, like a hobo just to ‘live a little, man. I won’t be a suit-and-tie slave yet, you know? I know my dad is rich but I want to be independent, man,’ and he even snorted cocaine from a monkey’s forehead. Then, this happened on Facebook:

And it was that same day that the monkey head-dust photo appeared, following five hundred likes and a fucking meme made for it on 4chan. com, that Tomás decided to send off his university Games Design application. He sometimes wishes he’d taken a gap year too, although he knows that even under different circumstances, even with a meme of his own face doing drugs off of an alpaca’s groin, he’d somehow find a way to live through the same decisions all over again, and he’d be sitting right where he is now, five years older, twice the pigeons, half the money, zero memes. <Module Name='Envy' ExceptionImplementation='true'/>. He does really hope for Yiyo’s band to succeed.

‘Hey man, listen, I have a favour to ask you,’ Tomás says.

‘Sure man, shoot,’ Yiyo says, making a gun with both hands.

‘It’s about Eva.’

‘Come on, it’s been long enough.’

‘It’s just this one last thing.’

‘You said that last time when you wanted me to give her that bag full of candles. She didn’t even remember having them.’

‘That was different.’

‘It’s always different.’

‘She just loved vanilla so much, I thought—’

‘So what is it this time?’

‘You know where she lives now, right?’

‘No.’

‘You said you did.’

‘I do, but not for you. You looked pretty fucked up after you gave her the candles.’

‘It’s a bill, man, a gas bill.’ Tomás hands him the letter and Yiyo turns it to look at the writing on the front of the envelope.

‘A bill?’

‘Yeah. Could you give it to her? It’s important. She’s expecting it.’

‘Alright, sure dude, but tonight I got band shit to do.’

Tomás sighs and looks at the shop windows. There’s an old blue CJ drum kit with a bent splash cymbal and black electrical tape holding the bass drum skin in place. Christmas lights are tangled around the cymbal stands.

‘So you still haven’t sold the drum kit, huh?’

‘Nope. It is a piece of shit after all.’

‘A real shame.’

‘I thought the lights would work, but I guess it’s August,’ Yiyo says, walking back to the door. ‘Sorry man, I’ve got to finish opening up. You want to come in or are you staying out?’

‘Nah, thanks. I’ve got to get to work. I just came to give you the bill.’

‘So how’s that going?’ Yiyo asks.

‘How’s what going?’

‘Well, the next one will be big.’

‘Good. Christmas lights might work for you,’ Yiyo says, stretching with a smile. ‘Good, good,’ he says while shaking hands with his first customer who just waits there nodding at nothing.

‘Yeah.’

‘Bye dude.’ Yiyo turns a cardboard sign by the door that now says OPEN and Tomás waves back even though the door’s now closed.

He lights a cigarette, stands and turns to cross towards the park that runs along the Mapocho River. In Santiago, anything with more than two trees is called a park, but this one’s really great because there’s a giant water fountain that sprays red and yellow and pink water and even music, although they mute it in the summer because people use it for pool parties and forget to wear clothes. He sees a young couple flying a kite together, and a stray dog that follows him (stray dogs always follow him) until it finds pieces of bread by a bin. He’s always found it funny that the whole of Santiago revolves around the Mapocho, the river of shit that crosses the city and divides it into those who have to live with it, and those who hope to some day sail on it. Plaza Italia cuts Santiago in two, into whites and browns, into rich and poor, into German and misspelt Spanish surnames, and if water could be sliced in half and made to flow in opposite directions, the river would do just that and its whirlpool would be right here, right where he now steps on his dead cigarette.

Then again, the Mapocho isn’t too bad because anything can look beautiful next to it, like having an ugly friend with you on a night out in town (which he knows is a shitty thing to think). There’s a plastic windmill salesman pulling a cart full of spinning reds and oranges. People sell everything on foot in this city. You’d think it’d be easier to just wait in some corner, let people come to you. That’s what he’d do, build a customer base, maybe even promote it online and make business cards with at least two telephone numbers and pay to appear in the Yellow Pages and… There it is again, the pigeons, the Sky, the not-doing-coke-on-a-monkey’s-head, the river splitting, and him just sitting in the middle, where no one knows if trash is sinking or getting pushed aside by the current, by the spinning colours and the broken Sandro tunes from the tiny speakers that could now spell out forgotten memes about him: all-your-base-are-belong-to-us, I Regret Nothing… But they really don’t.

The truth is that if it were your job to sell counterfeit Snicker bars and ChocoPanda ice-lollies, you’d also probably develop an instinct to escape, to run, to walk away. In Santiago you never really enter anything but you leave a lot. Tomás stands and the salesman asks him if he wants a windmill and Tomás promises that he’ll buy one later on the way home. The salesman tells him that he’ll be there all day and then asks another guy the same thing, but the other guy just says no.

He crosses the avenue again and turns on a small side street where his office is. Well, at least it used to be his. When the university announced that they would be cutting down their spending budget and many people lost their jobs, it seemed like the wrong thing to do to complain about having to share an office with Jaime. But there’s only one desk, so Tomás has to work on a small flat surface by the windowsill until Jaime leaves. Jaime is always there when Tomás arrives but at least he leaves early too, because creative minds, he says, are attuned to the power of sunrise (though you can’t really see the sun at all because of all the skyscrapers blocking it). Jaime once said it was OK that Tomás had to write by the windowsill because good writers can write anywhere. But when Tomás asked if he could work from home, Jaime said that no one really works at home. Either way, Tomás can’t complain. After all, Jaime let Tomás stay at his flat for nearly three months after the breakup without paying for as much as a beer. Sometimes though, he wishes the rent had been expensive as hell.

There’s a crowd gathering by the main door of the office building. They’re all wearing hiking boots, green jungle hats with nets on the back of the neck, and oversized military jackets filled with pins and badges and creases and holes. Some have banners that say ‘Blue Peace’ and ‘Unite against #GlobalWarming or suffer THIS’ with a photograph of a volcano erupting into an atomic mushroom cloud of reds and orange sparks in the background. The university shares the office building with Blue Peace, so every week Tomás and Jaime have to watch crowds start their marches towards the La Moneda Square along the river. Last week, the protesters were pissed off by the lack of media attention after their #WeAreJustAnimals naked protest campaign against animal-made clothing failed to get into the evening news. Fighting warmth in winter gets no support whatsoever.

He pushes through the crowd and a woman with a megaphone gives him a volcano banner. He takes it by the mushroom cloud and thanks her because they like being thanked, and she smiles at him as he walks inside. The elevator is still under maintenance, which is really just a Chilean way of saying BROKEN FOREVER since he’s never seen anyone come to maintain it. He takes the stairs instead and by the time he’s on the ninth floor he can hardly breathe. He should really stop smoking and go jogging and eat organic vegetables. He should ask the Blue Peace people for advice. His father, now sixty, told him once that he already has friends who’ve died of lung cancer. But, like his father, Tomás will stop smoking when he has his first kid (and then, also like his dad, never actually do it). At least that was the deal he’d had with Eva.

He opens the 934-A door to the offices lobby. He walks past the secretaries because he still hasn’t graded the students’ Game Ludonarrative Dissonance assignments from the beginning of the semester. He’s also not up to date with the attendance sheets for his seminars. They wouldn’t take long to do, but that’s also the reason why he never does them. He looks at the secretaries as he passes by and Anna sees him and stands to talk to him. He keeps on walking. Ever since she got pregnant, Tomás has found it easier to outwalk her.

‘Tomás, the tests, please!’ she shouts to him, holding her belly.

‘Sorry, I’m joining the protest today. This one’s with clothes.’ He shows her the volcano banner and he walks past office doors where there are people he’s still never even met. At the end of the long corridor is their boss, Pedro Milcock. Tomás hopes that Pedro doesn’t know about the assignments, and he probably doesn’t because even when Bimbo: The Elephant failed to sell, he told Jaime they were doing work that showed promise. Still, he’s only ever complimented Jaime for anything they both do, and Tomás is sure that Pedro knows that he doesn’t deserve to work there, that he’s just another pigeon living on someone else’s scraps. Jaime says this is all in Tomás’s head, but just to be safe Tomás always avoids Pedro. For example, once, on his way to his office, Tomás saw him starting to come out of a door at the other end of the corridor. Tomás went into the toilets that were next to him and locked himself in the handicapped cubicle. When he was about to come out, someone came in. Tomás looked under the door to see if he could recognise the shoes. He didn’t (who could ever do that?) and so he sat and heard that someone piss. FOR. AGES. When he came out, Pedro was looking at himself in the mirror, still pissing, and then frowned at him. Tomás walked straight out but he should have washed his hands first.

He opens his office door, door 405, right next to Pedro’s. Jaime turns on his chair and smiles at him.

‘Great, so now you’re a climate change activist. Cool, man,’ he says with a fist in the air. ‘You know those hippies are all wrong right? I only wish it were warmer. But hey, some of those girls must look good naked, despite all the hair,’ he laughs and Tomás nods and puts the volcano by the bin.

‘How are you?’ Tomás asks Jaime, but Jaime turns to look at his computer screen again.

‘You have to see this. Been trying out a new engine, Unreal 4. Check this out.’

Tomás sighs. ‘We don’t use Unreal 4.’

‘Not yet. Look, check it.’

Onscreen: a dark back alley with an old bar that has a light flickering and no people inside. When the lights turn on in the bar, Tomás can see the rain bouncing on the floor like pebbles, freezing in light before disappearing, as if lightning had struck.

‘Pretty cool, huh? Finally got the rain to come down.’

‘Looks great.’

‘It looks real. Look how big those drops are. Look at how they splash and make puddles. Sure, I don’t know how to stop the puddles from gathering water yet, but hey, I’m not sure what I can do with it yet anyway. I was thinking maybe a detective game would go down well with the whole rainy dark alley bar thing. Any ideas?’

‘Well, there’s already a game like that.’

‘Every damn time… Took me all weekend. Shit, so what’s this one called?’ Jaime sighs.

‘Heavy Rain.’

‘Fuck me…’ He closes down the dark alley. ‘I guess we still have Bimbo.’ He opens up a screen with the elephant, the sad fucking elephant condemned to fly without reason other than coins which can’t even buy anything in the game because they didn’t have time to come up with any items.

‘Hey man,’ Jaime starts, ‘do you think it would maybe look better if I applied underwater presets on the physics engine instead of flying ones? I mean, without a liquid backdrop, of course.’

‘Why would you do that? The game sucks no matter where it’s set.’

‘I know, but maybe it’ll change underwater. Part of the problem is that Bimbo sticks to the jumping animation, but underwater there’d be no jumping, it’d just be swimming.’

‘There’s still a floor in the ocean,’ he says. But what if the puddle gathered so much water, so many pebbles that it covered the whole of Santiago? What if out of a puddle, a mistake in physics, they could make a whole ocean where lightning is just dust particles that freeze nothing, and Bimbo can finally be the mistake he was destined to be and just float on forever? Playable mistakes are the hardest thing to program though, and Jaime could never pull them off on demand.

‘I guess. It’s too early for a Bimbo sequel anyway,’ he says, turning the elephant model that even underwater flies confused, contorted in choppy animation and low-res greys and blacks that stick out of its head and body in sharp polygons. The more you look at it, the more it kind of starts to look like a pigeon or…

‘Well, that’s enough for me today,’ Jaime says. He opens up the web browser on a dating site called GeeksWithoutKids.com. He scrolls down the PC Master-Race section (which just means old people) to a page full of photographs of women wearing thick black-framed glasses, pokéball earrings and Zelda Triforce tattoos over their Xbox Gamerscore points and PC Steam Achievement lists.

Tomás goes to the window and opens his IDEAS book on the small white surface next to it. He starts to open the window but Jaime turns and…

‘Could you wait a bit until I’m gone? I can’t stand those damn hippies. I feel that if you open the window we might get their BO from here. I’m about to leave anyway.’

‘Really? Where are you going?’

‘Date.’ He points at the screen.

‘It’s not even lunchtime.’

‘Well, they’re meant to be geeks after all.’

Tomás nods because he likes to stay alone in the office and use the real desk.

‘How do I look?’ Jaime asks him, standing up and putting his coat on. He’s balding on the sides and you can tell by the dark cracks on his cheeks that he had real bad acne, and why is it that people ask you how they look before doing something important? Can they change it? Would washing your face, rubbing a tissue on it, changing shoes or wearing a nice watch change anything at all if you’re an ugly fucker? Repairing Jaime’s cheeks would be like building a smooth parking lot inside the ridges of the Grand Canyon. It just can’t be done with today’s technology. He’s also wearing this fucking ridiculous red bowtie because he’s the kind of guy who thinks self-hatred is confidence, and those damn braces he isn’t ashamed of make him seem honest about it.

‘You look great.’ Tomás answers. ‘I mean, if you put a gun to my head,’ he says using his hand as a gun aimed at his left ear, ‘I’d lose the—’

There’s a bang on the window and they both jump and turn to it. A bird is dying on the other side of the sill after crashing against the glass.

‘Dude,’ Jaime says.

‘Fuck.’

‘Should have opened the window after all,’ Jaime laughs as he picks up his umbrella.

‘I’ll clean it up, don’t worry.’

‘Well, you kind of have to, I have to go, like, now.’

Jaime leaves and Tomás bends down in front of the window to see the bird. It’s shaking, black eyes still open, its wings wrapping the body to stillness. It’s the second time a bird has died on their window and he really should, once he’s done with the new game, print out bird silhouettes and stick them everywhere. He knows it works because he’s seen them stuck in other buildings around the city and he wonders why birds are so afraid of their own shadows that they refuse to touch them.

He opens the window and pokes the bird with his pencil. It doesn’t move so he takes out an A4 from the printer tray and uses it to grab and wrap it and then leaves it in front of himself on the keyboard. Would it still have crashed under Jaime’s ocean preset? Nothing can look painful underwater, even drowning. He takes out a cigarette and rubs the tip to let specs of tobacco fall on the bird. He looks for a pen inside the pen mug, finds a Bic, and takes its insides out to keep the plastic tube. He looks at himself on the black computer screen with the tube up his nose and then looks at the bird with the tobacco.

The climate change hippies are still downstairs shouting motivational slogans amongst themselves. Free our futures, free our futures, free… The bird opens its beak and shuts its eyes, and the pen falls off Tomás’s nose, and he stands and leaves the bird by the window and lights a cigarette. At least it’s not a pigeon.

He looks at his IDEAS book and writes FREE OUR FUTURES and draws a bird under it, but he knows he could never turn something so abstract into a game. He finishes his cigarette and looks at the time. He still has twenty minutes to kill before class and he wonders if Yiyo’s delivered the letter. Would Yiyo free his future? Would Eva write back or just appear at his office? Would they ‘talk it over’? He hates that douchebaggery, talk it over, which is really just C++LIFE code for <Function Name='TALKING A LOT'/>, too much and to the point of exhaustion and about nothing in particular, minor annoyances, the way her tone implied this or that, the way he’s sorry but he misunderstood that tone (which is like saying he isn’t sorry at all), the way she just didn’t have as much fun as they once did when tiring others with the same fucking jokes routine they shared for two whole years about this hipster in the metro they pretended to have conversations with and hey, man, yo, man, what’s up bro, check my beanie out, man, but there was no one there even wearing a hat… And then there’s the way they’ve both changed just because they’re older, which they’ll try to make sound like something positive with big words like EXPERIENCED and MATURE, but you’re OLD, you douchebag, you’re getting older, you’re just OLD, #oldandying. And that’s what happens when you talk it over. You agree to a wall of noise, and then you agree to silence.

He locks the office door from inside and turns the lights off. He kneels on the floor and crawls under Jaime’s desk and lies on his back looking up at the table. It’s in moments like these that he recognises himself as a teenager and it really gets to him, because if people can only see themselves as they want in secret, then the whole city is just filled with half-people, ghosts traversing through walls and convinced they can still dream when they’re just remembering, and then they disappear and it freaks everyone out, and like in the movies, they just don’t know yet that part of them is already dead.

Under the desk it’s an astrological display of chewing gum. Someone else has done before what Tomás is doing now. Someone has lain under the desk, just like him, and stuck about sixteen pieces of chewing gum underneath. He or she even took the time to connect some of them and Tomás is glad he’s sharing a stranger’s secret. They remind him of the times he and Eva would walk up the San Cristóbal Hill on summer weekend mornings and stay there until the stars came out and they would see the whole of Santiago light up for them, just for them, and somehow, in the sudden emptiness of city nights, he would know, he knew, that he could spend all of his life watching the streets and the sky flickering like a dying candle in the dark.

The pieces of gum move overnight. He’s sure of it. No one apart from Jaime and himself can get into the office and so who could be coming in (or why) to move them is beyond him but it happens. Could it be Lolita, the remover of bench names? Or was it Jaime’s troll droll on the shelf that comes to life at night to do it? It’s always turned to face the desk.

‘What are you looking at?’ he asks the doll but even if it did answer, Tomás likes that their agreement is a silent one.

What yesterday was a perfect circle of seven pieces of gum is now a square. He turns to the troll doll on the shelf that looks both old and young at the same time, which is pretty much what an internet troll is too, and he notices its big toothless smile and bulging eyes. He checks his watch and it’s time for him to go to class but he could fall asleep under the desk right now. The rug is comfortable enough and he already used his bag as a pillow once. He must remember to build the bed frame when he gets home but only if…

He puts his jacket back on, gets his IDEAS book from the window and takes four random books from the shelf (Chaos Theory 1, Ludonarrative Dissonance, Physics Engines, and Unreal 4) to make his students believe that he’s well-prepped for class. He walks up to the dead bird wrapped in paper, shakes the tobacco dust off of it, and grabs it to put it in a bin outside.

Towards the main door he sees Anna the secretary putting her phone down and standing up and grabbing her belly. Tomás keeps walking and shows her the dead bird.

‘Tomás, please, those grades, when will—’

‘I can’t right now, something died in my office.’