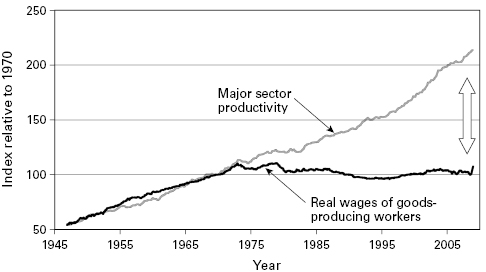

Figure 2 Productivity and average real earnings

Source: Bickerton and Gourevitch 2011, using data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics

The American middle class is vanishing, as can be seen vividly in figure 1. The middle class’s share of total income fell 30 percent in forty-four years. This is a big change for the United States; one that we need to comprehend in order to adapt to or change. We have to look beyond this graph in order to understand what is happening. Why did the Pew Research Center begin its graph in 1970? What can we expect to happen in the near future?

There was good reason to start in 1970. Real wages stopped growing at that time, as shown in figure 2. Wages had grown with the rest of the economy since the end of the Second World War. National production continued to grow after 1970, but wages did not. Somehow wages were disconnected from what we all regarded as economic growth.

Figure 2 Productivity and average real earnings

Source: Bickerton and Gourevitch 2011, using data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics

This disconnect has been noticed widely. John Edwards, a presidential candidate, observed in 2004, “We shouldn’t have two different economies in America: one for people who are set for life, they know their kids and their grand-kids are going to be just fine; and then one for most Americans, people who live paycheck to paycheck.”1

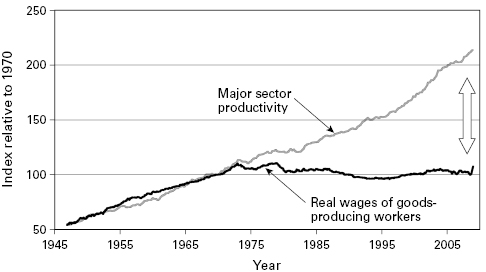

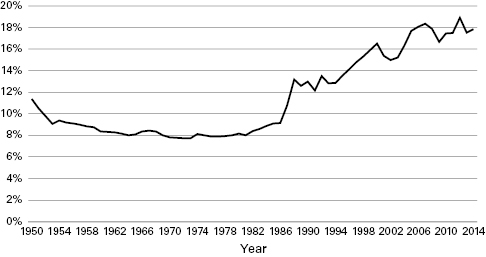

Where did the rest of the national product go? Not to the lower group shown in figure 1. It went instead to the upper group as shown in figure 3. This well-known graph comes from Thomas Piketty, author of Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century, and his colleagues who have developed data for the richest 1 percent of the population for many countries as far back as the data allow. The top group in figure 1 contains 20 percent of the population, and the path of what is called the “one percent” shows the pattern. Chrystia Freeland calls this group “the plutocrats.” A graph of the next 19 percent looks like figure 3, albeit not quite as steep. And a graph of college graduates—representing something close to the top 30 percent of the population—shows that the educational premium has risen as well. The higher one goes in the income distribution, the more rapid the growth of incomes in recent decades, and the pattern of differential growth extends to the upper 20 percent of the income distribution.2

Figure 3 Top 1 percent income share in the United States

Source: http://www.wid.world/

Graphs like figures 2 and 3 have become common since the global financial crisis of 2008, although the two curves often are discussed by different people. The decline in the growth of workers’ compensation has been cited as a cause of the 2008 financial crisis as workers borrowed on the security of their houses to sustain their rising consumption that rising incomes had supported before 1980. And the growth of high incomes has been the stuff of recent political discussions as fundraising looms ever more important in American politics.

I argue here that the disparity between the lines in these figures has increased to the point where we should think of a dual economy in the United States. The upper sector represented in figure 1 contains 20 percent of the population. Their fortunes have separated from the rest of the county; the low-wage sector contains the remaining 80 percent whose income is not growing. I analyze this disparity using this simple theory, and I examine the important role that race plays in political choices that affect public policies in this dual economy.

W. Arthur Lewis, a professor at the University of Manchester in England, proposed a theory of economic development in a paper published in 1954. He noted that development did not progress only country by country, but also by parts of countries. Economic progress was not uniform, but spotty. Ports where merchants organized trade in and out of a county might well grow rich before the country as a whole. Parts of a country might grow apart as a result. Lewis wanted to generalize from examples like this to learn how the parts of such an economy related to each other.3

Lewis assumed that developing countries often have what has come to be called a dual economy. He termed the two sectors, “capitalist” and “subsistence” sectors. The capitalist sector was the home of modern production using both capital and labor. Its development was limited by the amount of capital in the economy. The subsistence sector was composed of poor farmers where the population was so large relative to the amount of land or natural resources that the productivity of the last worker put to work—called the “marginal product” by economists—was close to zero. The addition of another farmer would not add to the total production. The new worker would be like a fifth wheel on your car.

Lewis followed the practice of economists by summarizing whatever differences there might be in parts of an economy into just two sectors. To take the example of a port and the countryside, Lewis saw the port as the capitalist sector and the countryside as the sector of subsistence farmers. He assumed there were lots of farmers on limited land, so that meant they were poor farmers. His model is not applicable to every country with a port or an industrial area, but only to countries in which the rest of the economy is characterized by a surplus of workers.

Lewis was thinking of countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America where there were many farmers engaged in small-scale agriculture and only a few areas where long-distance trade or industrial production was taking place. China was perhaps the largest country he considered. It had expanding trade and production areas on its coast where it was communicating with European and American traders, and it had desperately poor farmers in the center of the country who were producing barely enough for their families to get by. Smaller Asian countries also were dual economies, and several of them grew rapidly in the 1960s and 1970s as they expanded to bring almost the whole population into the capitalist sector. Japan, Korea, and Malaysia are known for these “growth miracles.”4

Lewis noted that wages in the capitalist sector were higher than in the subsistence sector because work in the port or factory was aided by capital and required more skills than farming. In addition, capitalists constantly were seeking to hire more workers to expand production. He argued that wages in the capitalist sector were linked to the farmers’ earnings because capitalists needed to attract workers to their sector by offering a premium over farming wages to induce farmers and farmworkers to leave their familiar homes and activities.

Lewis argued that this linkage gave capitalists an incentive to keep down the wages of subsistence workers. Business leaders in the capitalist sector want to keep their labor costs low. The wages they need to offer are the sum of the basic low wage plus the premium offered to attract low-wage workers to their sector. The business leaders cannot influence the premium, but they can work to keep wages in the subsistence sector low.

Since this is an important part of the Lewis model, it is worth quoting his words. He said, “The fact that the wage level in the capitalist sector depends upon earnings in the subsistence sector is sometimes of immense political importance, since its effect is that capitalists have a direct interest in holding down the productivity of the subsistence workers.” Going further and equating capitalists with imperialists, he continued, “The imperialists invest capital and hire workers; it is to their advantage to keep wages low, and even in those cases where they do not actually go out of their way to impoverish the subsistence economy, they will at least very seldom be found doing anything to make it more productive.”5

The dynamics of this dual economy came from the expansion of the capitalist sector. Capital initially was scarce, giving rise to isolated locations of factory employment. Savings initially were low because subsistence workers consume all or close to all of their incomes. Savings increased as profits and rents grew in the capitalist sector, and the reinvestment of profits to purchase or construct more capital led to the expansion of the capitalist sector. Although the capitalist sector initially appeared as a series of islands, they can be seen as one sector due to the mobility of capital that equalized the earnings from capital. Not every island needed to have the same average productivity, but profits from the last bit of investment in each case—again, marginal profit to economists—would be the same. If a new machine or productive unit was added, it would be equally productive on any island.

Lewis assumed that the difference between the two sectors was not simply in their incomes, but also in their thought processes. Subsistence workers think only of surviving, or living day to day, from paycheck to paycheck. Businessmen in the capitalist sector are maximizing profits and trying to do so by finding the best place and activity to invest. That is the process that results in the marginal profit being the same in different parts of the capitalist sector of a dual economy.6

This model received a lot of attention when it was published, and Lewis was honored with a Nobel Prize in Economics for it in 1979. He noted the link between wages in the two sectors without detailing the transition from one to the other. Some years later, other economists proposed that the transition be considered a rational choice by the worker. They extended Lewis’s assumption of economic rationality from the capitalist to the subsistence sector. They argued that a farmer thinking of moving to the city was attracted by the wage available in the city, which was substantially higher than the wage he was earning in the countryside. He would leave if his expected wage in the city would be larger; the expected wage is the product of the wage differential and the probability that the worker would find a high-paying job in the city. The farmer was assumed to anticipate both the higher wage and the difficulty of obtaining a job that paid this wage.7

The economists recognized that the effort to transfer into the capitalist sector was neither certain nor swift. It was not enough to move to the city; the aspiring worker had to find a good job. We know that this was hard to do from the massive slums that surround all big cities in developing countries. These slums are full of migrants who came to the city and then failed to find a good job. The economists recognized this difficulty by noting that the migrant only had a probability—hardly a certainty—of finding a job in the capitalist sector.

Many factors influenced the fortunes of the aspiring migrants, from their prior education to their personality, from who they knew in the city to pure luck in meeting new people. The economists did not ignore these individual traits; they summarized the mostly unobservable characteristics and events into a probability distribution. And they implicitly saw this distribution as the sum of many underlying influences more or less randomly distributed among the migrants, yielding a bell-shaped probability distribution.8

What then determined the average probability of finding a good job in the city? The many determinants of the average can be divided into supply and demand. The supply of new jobs will be increased if the growth of the capitalist sector is rapid. And the demand for new jobs in the capitalist sector will be increased if it is easy for farmers to go to the city and try their chances. These factors clearly vary from time to time and place to place.

The names for the sectors that Lewis chose were transformed into urban and rural sectors in articles using the Lewis model to analyze developing countries. I transform them further as I apply the Lewis model to the United States today. I observe the division of the American economy into two separate groups in a different way than the typical division of urban and rural, but very much in the spirit of Lewis’s model. I distinguish workers by the skills and occupations of the two sectors. The first sector consists of skilled workers and managers who have college degrees and command good and even very high salaries in our technological economy. I call this the FTE sector to highlight the roles of finance, technology, and electronics in this part of the economy. The other group consists of low-skilled workers who are suffering some of the ills of globalization. I call this the low-wage sector to highlight the role of politics and technology in reducing the demand for semi-skilled workers.

The wages in the two sectors then can be seen in figures 2 and 3. Figure 2 shows the stagnation of average wages for the last generation. The workers with stagnant wages are the analogue of Lewis’s subsistence sector, although these workers earn well above what we think of as the earnings of actual subsistence farmers. (Lewis noted that wages typically were above that primitive threshold even in subsistence farming.) Figure 3 shows the wages of the top earners in the FTE sector. As noted already, the wages of others in this sector have risen in the last generation, although not at the same rate as the top 1 percent.9

The division between the two sectors divides the economy unevenly. The FTE sector includes about 20 percent of the population, while the low-wage sector contains the other 80 percent. These numbers come from the Pew Research Center’s report that contains figure 1. The middle group contains households earning from two-thirds to twice the median income, that is, from $40,000 to $120,000 for a family of three in 2014.

The middle and lower groups of families were 50 and 30 percent respectively of the population. The proportions in the three groups have changed a bit over time. There were 10 percent more people in the middle class in 1970, 60 percent instead of 50 percent, and they were better off as the figure illustrates. The other groups were each about 5 percent smaller in 1970, and the population gains in the upper and lower groups accentuate the division between the two sectors of the dual economy.

Whites and Asians were less likely to be in the lower group and more likely to be in the upper group than the national average. Blacks and Latinos were more likely to be in the lower group and less likely to be in the upper group. Blacks became less likely to be in the lower group over time, although blacks today still are far less likely than whites or Asians to be in the upper group. African Americans were advancing into the middle class before the financial crash of 2008, but they have been frustrated since then by losing housing capital and good jobs. Latinos were more likely to be in the lower group over time. Recent immigrants from Mexico and other Latin American countries are in danger of being trapped in the low-wage sector.10

It may make these numbers more meaningful to think of our population as being roughly divided between groups that were here before 1970 and groups that have come to America since then. In the group that has been here longer, white Americans dominate both the FTE sector (the upper group in figure 1) and the low-wage sector, while African Americans are located almost entirely in the low-wage sector. In the group of recent immigrants, Asians predominantly entered the FTE sector, while Latinos joined African Americans in the low-wage sector. Asian immigrants are only slightly more than 5 percent of the population, while Latino immigrants have grown to around 17 percent and now are more numerous than African Americans.

Phrased differently, the FTE sector is largely white, with few representatives from other groups. The low-wage sector is more varied, with a mix of whites, blacks, and Latinos (“browns”). The low-wage sector is about 50 percent white, with the other half composed more or less equally of African Americans and Latino immigrants.

figure 1 reveals the changes in incomes before taxation. When taxes and government benefits are subtracted and added, the resulting pattern of differential growth is softened but not eliminated. Family income for working families has stayed constant since the 1970s, but the disposable income of these families has risen as a result of increasing tax incentives and benefits for working people. The contrast between the two sectors is not erased by shifting to disposable income, but the division between them is reduced. The United States still has the most unequal distribution of after-tax income in the world for people under age 60, that is, for working people. Retail stores catering to the vanishing middle class are failing.11

The rising inequality of income has led to an increase in the inequality of wealth in America. People with high incomes save more of their income than poorer people, and high earned income resulted in high capital growth. The wealth share of the top tenth of the top 1 percent has tripled since 1978 and now is near 1916 and 1929 levels. The share of the middle class fell from 35 percent of national wealth to 23 percent in 2012. The middle-class share of wealth is lower than the middle-class share of income in figure 1, and it suffered a similar fall.12

The link between the two parts of the modern dual economy is education, which provides a possible path that the children of low-wage workers can take to move into the FTE sector. This path is difficult, however, and strewn with obstacles that keep the numbers of children who make this transition small. Thirty percent of Americans have graduated from college, and this provides an upper bound of membership in the FTE sector, but a college education does not by itself guarantee a high and rising income. The choice of major, the state of the business cycle, and other less intangible personal characteristics affect the relation between education—called human capital by economists—and income. Just as relocating to the city in the original Lewis model did not guarantee the migrant farmworker would find a good urban job, a college graduate today is not certain to find a job in the FTE sector.

In addition, the path to the FTE sector is difficult because education requires a change of attitude as well as an increase in knowledge. This follows the Lewis model where people in the two sectors of the economy are assumed to think differently. Subsistence farmers think only of surviving for another season, while capitalists maximize profits over a longer period.13

Education has a long payoff and requires attention over many years before its benefits are apparent. This difficulty may be seen within the FTE sector as similar to the issues in saving for retirement or persuading children to continue piano lessons. In addition, the gains from education are varied, and the educational system needs to be structured to help students learn many dimensions of knowledge. Problems in the education system that result from politics and societal decisions are in addition to the problems of individual students.

Many people in the low-wage sector see the gains that accrue from moving into the FTE sector, but they know that any attempt entails risks. Despite all the efforts that low-wage-earning parents can muster for their children, there is only a small probability that their children will be able to complete this long transition and achieve the desired move into the FTE sector. This probability is determined by the FTE sector’s limitation of schools funding and by the attitudes of individual students.

Lewis argued that the size of the capitalist sector (FTE sector in my version) was limited by the amount of capital. Working within a traditional economic framework, Lewis interpreted capital as being factories and infrastructure. Research over the past fifty years since he created his model has expanded this concept; I draw on this research to detail the kind of capital that is needed in the FTE sector in my version of a dual economy. This sector is limited by the availability of three kinds of capital. The first kind is physical capital—machines and buildings—used to produce products that people will buy. The second kind is what economists call human capital, the gains from education. The transition from the low-wage sector to the FTE sector involves education because human capital is needed for almost all jobs in the FTE sector. The third kind of capital is social capital, which means maintaining the widespread trust of others and interpersonal networks that help people get jobs, find opportunities for advancement, and provide feedback on innovative ideas.14

Robert Putnam, who popularized the concept of social capital among social scientists, stressed the importance of education in his most recent book, Our Kids. This collection of interviews makes the argument that our economy has separated into rich and poor. Putnam identified the division between them as a college education. I argue here that people in the FTE sector, the rich, are less numerous than Putnam implied because not all college graduates find jobs that pay well. Despite this minor difference, Putnam’s vivid interviews provide human examples of many of the points made here.15

The FTE sector functions in the long run as standard economic growth models predict. Capital—physical, human, and social—comes from savings and produces more output. It is important to include social capital on both the input and output sides. Trust and networks are important for productivity, and the capital of finance, for example, is not primarily physical capital. This is not the place to try and calculate the productivity of finance, but it clearly is a growing part of national income. The FTE sector retains much of the favored position of white males that characterized earlier growth. Women and blacks have made progress but there is still a long way to go toward equality. They are still underrepresented in positions of wealth and high incomes.16

There is an important asymmetry between figures 2 and 3. Significantly fewer people are described in figure 3, but they exert far more political power. One purpose of this book is to describe the framework within which many political decisions are made. Members of the FTE sector are largely unaware of the low-wage sector, and they often forget about the needs of its members. In addition, the top 1 percent exerts disproportionate power within the FTE sector, and its members’ political decisions accentuate the differences between the two sectors because they would rather lower their taxes than deal with societal problems, as Lewis argued. Their political power has inhibited full recovery from the crisis of 2008 by preventing fiscal-policy expansion.17

The members of the low-wage sector are diverse, but many who aspire to move into the FTE sector through education face growing difficulties. The first reason is the geography of residents. Poverty is concentrated in inner cities, and schools in those areas are famously challenged in their ability to engage students in academic pursuits. Attempts to deal with school problems have led to universal testing, which leads teachers and students to focus on elementary skills. The areas of education that are not tested increasingly are neglected. Gone is the excitement of exploring more advanced areas. Gone is attention to intangible aspects of education that promote social capital. Support for maintaining these obstacles often is presented in the context of keeping African Americans “in their place.” While blacks are a minority even in the low-wage sector, the focus on blacks in public and political discussions helps obscure the problems of low-wage whites.18

The result is that education, which long ago was a force for improvement of the entire labor force, has become a barrier reinforcing the dual economy. For most young people, education is appropriate for the economy they are growing up in, and the contrast between suburban schools for the FTE sector and urban schools for the low-wage sector is increasing. The decline of racially integrated schools is part of this process, as African Americans and now also Latinos are concentrated in urban schools, and the politics of improving urban schools has become entangled with America’s long history of racial politics. The problems of American education cannot be understood without understanding the racial and gender history of the United States. I review this history in chapter 5 to provide background for the analysis of politics today.