Ever heard of William Higinbotham? He’s the guy who invented the world’s first video game. But he never made a cent off his invention and hardly anyone has heard of him. Uncle John thinks it’s time he got the credit he deserves.

How would you feel if a nuclear reactor came online just down the street from your house? Would knowing that it was just a “small” research reactor, dedicated to finding “peaceful uses” for atomic energy, make you feel any better? That’s what happened in 1950 at the Brookhaven National Laboratory in Long Island, New York.

Despite all of its public assurances, local residents were visibly concerned about the potential dangers of the new plant. One way the facility tried to ease public fears was by hosting an annual “Visitor’s Day,” so that members of the community could look around and see for themselves what kinds of projects the scientists were working on. There were cardboard displays with blinking lights to look at, geiger counters and electronic circuits to fiddle with, and dozens of black-and-white photos that explained the different research projects underway at the lab.

In other words, Visitor’s Day was pretty boring.

In 1958 a Brookhaven physicist named William Higinbotham decided to do something about it. Years earlier, Higinbotham had designed the timing device used to detonate the first atomic bomb; now he set his mind to coming up with something interesting for Visitor’s Day. “I knew from past visitor’s days that people were not much interested in static exhibits,” he remembered. “So that year, I came up with an idea for a hands-on display.”

On average, people blink 10,080 times a day.

Looking around the labs, Higinbotham found an electronic testing device called an oscilloscope, which has a cathode ray tube display similar to a TV picture tube. He also found an old analog computer (modern computers are digital, not analog) that he could hook up to the oscilloscope in such a way that a “ball” of light would bounce randomly around the screen.

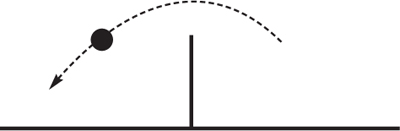

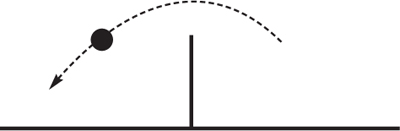

“We found,” Higinbotham remembered, “that we could make a game which would have a ball bouncing back and forth, sort of like a tennis game viewed from the side.” The game he came up with looked kind of like this:

Two people played against one another using control boxes that had a “serve” button that hit the ball over the net, and a control knob that adjusted how high the ball was hit. And just as in real tennis, if you hit the ball into the net, it bounced back at you.

It took Higinbotham two hours to draw up the schematic diagram for “Tennis for Two,” as he called it, and two weeks of tinkering to get it to work. When Visitor’s Day came around and Higinbotham put it on a table with a bunch of other electrical equipment, it only took the visitors about five minutes to find it. Soon hundreds of people were crowding around it, some standing in line for more than an hour for a chance to play the game for a minute or two. They didn’t learn much about the peaceful applications of nuclear energy that Visitor’s Day in 1958. But they sure had fun playing that game.

Higinbotham didn’t have an inkling as to the significance of what he’d done. “It never occurred to me that I was doing anything very exciting,” he remembered. “The long line of people I thought wasn’t because this was so great, but because all the rest of the things were so dull.”

Seeing is believing: Frogs use their eyeballs to push food down their throat.

So what happened to Higinbotham’s video tennis game? He improved it for Visitor’s Day 1959, letting people play Tennis for Two in Earth gravity, or low gravity like on the moon, or very high gravity like that found on Jupiter.

Then, when Visitor’s Day was over, he took the video game apart and put the pieces away. He never brought them out again, never built another video game, and never patented his idea.

Willy Higinbotham would probably be completely forgotten today were it not for a lawsuit. When video games began taking off in the early 1970s, Magnavox and some other early manufacturers began fighting in court over which one of them had invented the games. A patent lawyer for one of Magnavox’s competitors eventually learned of Higinbotham’s story and brought the Great Man into court to prove that he, not Magnavox, was the true father of the video game.

In 2001 Americans spent more on video game systems and software—$9.4 billion—than they did going to the movies—$8.35 billion. What did Higinbotham, who died in 1994, have to show for it? Nothing. He never made a penny off his invention. Not that he could have—he worked for a government laboratory when he invented the game, so even if he had patented the idea, the U.S. government would have owned the patent.

“My kids complained about this,” he joked, “And I keep saying, ‘Kids, no matter what, I wouldn’t have made any money.’”

For more about the history of video games, follow the

bouncing ball to page 180 for “Let’s Play Spacewar!”

Dolphins sometimes play chase in long lines, like people doing a snake dance or snap-the-whip. Sailors, seeing this long line of something moving in the water, have sometimes reported seeing huge sea serpents.

It’s easy to spot someone with hexadectylism: six fingers on one hand or six toes on one foot.