Source: Sciabarra [1995] 2000, 278; 2000, 380.

Chris Matthew Sciabarra

Nearly forty years ago, as a student at New York University, I had the privilege of studying and interacting regularly with key figures in the traditions of both Austrian economics and Marxian social theory. Among the former were such scholars as Israel Kirzner, Mario Rizzo, Gerald O’Driscoll, Murray N. Rothbard, and Don Lavoie; among the latter were theorists in economics (James Becker), sociology (Wolf Heydebrand), and political philosophy (my doctoral dissertation adviser, Bertell Ollman).

What I learned at the time was that both traditions had utilized elements of a “dialectical” methodology, rooted in ancient Greek philosophy and first articulated as a theoretical approach in the works of Aristotle. Such dialectical methods emphasized that in our exploration of any problem, it was necessary to grasp that problem from different “points of view,” elucidating its interrelationships with other problems—all embedded in a larger system that developed over time. Understanding the wider context of a single problem by comprehending it from different vantage points and on different levels of generality would make transparent the relationships among diverse problems as both preconditions and effects of the system they jointly constituted.

While I would never claim to be the first “dialectical libertarian”—precisely because I have argued that a dialectical sensibility has informed the writings of many significant thinkers in the classical liberal and libertarian traditions throughout intellectual history—I was one of the first writers to identify explicitly these dialectical tendencies in those traditions; and, to my knowledge, I remain the first person to use the actual phrase “dialectical libertarianism” to name this paradigmatic methodological approach to the defense of liberty.

My usage of this phrase was met with resistance by colleagues on both the left and the right. There were colleagues who viewed Marxism as having a monopoly on—or a virtual identity with—dialectical method, and who dismissed my claims on the face of it. And there were colleagues who were aghast to see anybody connect a libertarian politics to a method that they decried as “Marxist,” and hence as anathema to the project for liberty. In a sense, critics from both the left and the right accepted the false premise that dialectics was an exclusively Marxist “construct.” The mere mention of the word “dialectics” conjured up images of the “thesis-antithesis-synthesis” waltz typically associated with Hegel (even though that triad more appropriately belonged to Fichte) or the Marxist historical materialist dismissal of logic as a “bourgeois” prejudice. Indeed, some Marxists had argued that dialectics “transcended” logic, becoming a means of “resolving” actual logical (and hence, ontological) contradictions, thus showing that “A” and “non-A” were one and the same. (They seemed to have forgotten that even the law of noncontradiction contains a contextual proviso: a thing cannot be A and non-A at the same time and in the same respect.)

In modern and postmodern social theory, the terms of the discussion have clearly been shaped by the left. Marx himself had derided bourgeois theorists for putting forth a dogmatic, ahistorical, atomistic notion of human liberty that saw individuals as entirely separate from one another. Like Robinson Crusoe on a desert island, the individual depicted in the “Robinsonade” narrative of the bourgeois theorists is unrelated to other individuals and to any social or historical context. For the most part, unfortunately, Marx’s opponents in mainstream classical and neoclassical economics failed to challenge this critique of the atomistic theory of the individual. Even worse, their own static conceptions of perfect competition posited a rationalistic model of Economic Man in possession of perfect knowledge, a model that reflected the very “Robinsonade” narrative that Marx rejected.[1]

But as Friedrich Hayek and others have pointed out, it was not unusual for the left

to define the terms of scholarly discussion, for even the word “capitalism” was a

product of the socialist conception of history (“History and Politics,” in Hayek 1954,

15). It took a major effort by twentieth-century Austrian thinkers—such as Hayek and

his teacher, Ludwig von Mises—to provide a thorough reconceptualization of the market

society and its foundations. As members of the Austrian tradition founded by Carl

Menger, these thinkers viewed the market in dynamic, institutional, historical, and

contextual terms. And others in the libertarian intellectual tradition—Ayn Rand,

for example—posited a version of “capitalism: the unknown ideal,” which refused to

disconnect the defense of liberty from the identification of the larger context that

made liberty possible.

And so, it became the self-conscious goal of my “Dialectics and Liberty Trilogy” to recapture dialectics, “the art of context-keeping,” by severing its connection to the left, and reclaiming its rightful place as a handmaiden of logic and an essential methodological tool that might help us to understand the various forces that undermine—or nourish—the possibility of human freedom.

Though some of my early essays (for example, Sciabarra 1987) focused on “the crisis of libertarian dualism”—the problems that were inherent in nondialectical, atomistic, utopian approaches to the defense of liberty—it wasn’t until the completion of my 1988 doctoral dissertation, “Toward a Radical Critique of Utopianism: Dialectics and Dualism in the Works of Friedrich Hayek, Murray Rothbard, and Karl Marx,” that the theoretical outline of my intellectual project became fully apparent. It is somewhat ironic that my work was nurtured under the mentorship of Marxist social theorist Bertell Ollman. Ollman had developed a deep appreciation for the work of many libertarian thinkers. He was a Volker Fellow who worked for Hayek at the University of Chicago in 1959–1960 and interacted with such libertarians as Murray Rothbard and Leonard Liggio in the Peace and Freedom Party throughout the 1960s in opposition to the war in Vietnam. And while few libertarians embraced the direction of my work, some thinkers, such as Don Lavoie, Douglas B. Rasmussen, and Douglas Den Uyl, who had embraced dialectical themes in their own work, provided me with enthusiastic support. Ultimately, the reframing of libertarian social theory as a dialectical project became one of the primary goals of my lifelong intellectual journey.

The first book in my trilogy was Marx, Hayek, and Utopia, which was published in 1995 by the State University of New York Press. It had actually been slated for publication in 1989 by a West German press, Philosophia Verlag, but they went out of business, and the book’s publication was long delayed. Perhaps there is some symbolism in the fact of its delay—since there is no longer an East and West Germany to talk about!

The book built upon the Marx and Hayek portions of my dissertation and explored provocative parallels between the theoretician of “scientific socialism” and the Austrian “free market” economist, highlighting their surprisingly convergent critiques of utopianism and their mutual appreciation of context in defining the meaning of political radicalism.

For example, Hayek, in his emphasis on process and spontaneous order, enunciated a profoundly dialectical critique of utopianism. Hayek rejected both collectivist and atomist conceptions of the human being. For Hayek, since no human being can know everything there is to know about society, people cannot simply redesign it anew. Human beings are as much the creatures of their context as they are its creators. His rejection of utopian social planning is, at root, a repudiation of what he calls “constructivist” rationalism. The utopians rely on a “pretense of knowledge,” Hayek argued, in their attempts to construct a bridge from the current society to an ideal future one. Whereas the collectivists criticized bourgeois theorists for embracing “ahistorical” and “state of nature” arguments for capitalism, they themselves embraced an ahistorical, exaggerated sense of human possibility in their projections of an ideal communist society. Marx was critical of this “constructivism” in the works of the utopian socialists, but his own work succumbs to the same constructivist impulse. Implicit in his communist ideal is the presumption that human beings can achieve god-like control over society, as if from an Archimedean standpoint, virtually eliminating unintended social consequences such that every action brings about a known effect. Hayek (1973, 14) saw this as a “synoptic delusion,” an illusory belief that one can live in a world in which every action produces consistent and predictable outcomes. And, invariably, the quest for total knowledge becomes a quest for totalitarian control.

This Hayekian critique of nondialectical, utopian thinking is based on what Troy Camplin (2017) has characterized insightfully as “a blank slate view of the world.” In such a view, he writes,

you can completely dismiss everything that came before and create something completely, radically new in the world. . . . If the mind is a blank slate, we can write anything onto it—we can create through education the socialist man, if we so desire. This gives us a blank slate view of society. That is, we can simply shelve everything that’s ever been done, all of human history and experience, and create the world anew. (110)

Camplin’s insights are ultimately critical of any such approach even within libertarianism; it is simply not the case that we can create a new “libertarian man” or “libertarian woman”—for this completely acontextual, ahistorical view is a hallmark of utopian, rather than genuinely radical, social thought.

Whatever problems one might detect in Hayek’s various theories of social evolution (and I discuss these in Marx, Hayek, and Utopia), I believe that he contributes much to a dialectical libertarian social theory in his seminal work on the corrosive nature of government control, The Road to Serfdom. He does not focus on the one-dimensional economic effects of state regulation, but instead on the insidious, multidimensional effects of statism—how its consequences redound throughout a nexus of social relations: economic, political, and even social-psychological. In other words, Hayek analyzes statism not only as a politico-economic scourge, but as a phenomenon whose effects can be measured on different levels of generality and from different vantage points.

For Hayek, “the most important change which extensive government control produces is a psychological change, an alteration in the character of the people.” There is a social-psychological corruption at work, therefore, in which causes and effects become preconditions of one another, part of a system of mutually reinforcing processes. “The important point is that the political ideals of a people and its attitude toward authority are as much the effect as the cause of the political institutions under which it lives,” he writes (Hayek [1944] 1994, xxxix). This is a system, then, of mutual implications, of reciprocal connections between social psychology, culture, and politics:

Freedom to order our own conduct in the sphere where material circumstances force a choice upon us, and responsibility for the arrangement of our own life according to our own conscience, is the air in which alone moral sense grows and in which moral values are daily re-created in the free decisions of the individual. Responsibility, not to a superior, but to one’s conscience, . . . the necessity to decide which of the things one values . . . and to bear the consequences of one’s own decision, are the very essence of any morals which deserve the name. That in this sphere of individual conduct the effect of collectivism has been almost entirely destructive is both inevitable and undeniable. A movement whose main promise is the relief from responsibility cannot but be antimoral in its effect, however lofty the ideals to which it owes its birth. (231–32)

Hayek understood that under advancing statism, culture tends to both promote and reflect those social practices that undermine individual self-responsibility. Likewise, a free society is one in which the culture tends to promote and reflect those social practices that require individual self-responsibility. For Hayek, political change is built on a slow and gradual change in cultural mores, traditions, and habits, which are often tacit; trying to impose such change, without the requisite cultural foundations, is doomed to failure. Moreover, Hayek argued, those cultural foundations are reflective of the historically specific circumstances of a particular time and place. Despite having often been derided as a conservative, Hayek embraced the essence of a radical, rather than a utopian, approach. “[W]e are bound all the time to question fundamentals,” he said; “it must be our privilege to be radical” (Hayek [1967] 1980, 130).

Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical, the second book in my trilogy, was published by Pennsylvania State University Press in 1995 (and a second edition by that press in 2013). Russian Radical generated enormous controversy for its two novel claims: First, that Ayn Rand, like any individual, was born in a particular place and at a particular time. She came to intellectual maturity in the waning days of Silver Age Russian culture—a culture marked by Nietzschean themes and by the use of literature as a guide to revolutionary action. But it was also a culture imbued with a dialectical sensibility—taught by the professors of the courses she attended and the textbooks that she read as a student at the University of Petrograd, from which she graduated in 1924 (see especially Sciabarra [1995] 2013, part I, and appendices I, II, and III; 2017). And second, that this dialectical sensibility would come to thoroughly permeate her approach to radical libertarian social analysis.

Rand, of course, would not have self-identified as either a “dialectical” thinker or as a “libertarian,” since she typically linked the former term to the historical materialists she encountered in the Soviet Union and rejected the latter term because of its use by anarcho-capitalists, whose position on the nature and necessity of government she repudiated. But this is irrelevant.[2]

In Russian Radical, I illustrate how Rand used dialectical tools not only throughout the structure of her philosophy (discussed in part II of the book, “The Revolt Against Dualism”), but also in the structure of her analysis of social problems (discussed in part III, “The Radical Rand”). By no means did Rand reject the law of noncontradiction or deny the existence of logically opposed, true alternatives (such as existence versus nonexistence, life versus death, good versus evil, and so forth). We can clearly see, however, that Rand regarded many dualities as “false alternatives” and that her dialectical revolt against dualism is a revolt against false alternatives. For Rand, such false alternatives are often variants of the mind-body dichotomy, which she rejects in all its manifestations: the spiritual versus the material, the analytic versus the synthetic, the rational versus the empirical, logic versus experience, reason versus emotion, morality versus prudence, theory versus practice, and so forth. Such false dichotomies obscure the essentially integrated nature of human being. Much the same can be said of Rand’s rejection of all the other false alternatives generated by modern philosophy, such as intrinsicism versus subjectivism in epistemology, classicism versus romanticism in aesthetics, deontologism versus consequentialism in ethics, and socialism versus fascism in politics.

But there is a subtlety in Rand’s analysis that some of her defenders and detractors often miss, for even when she identified “true” dichotomies—that is, those things and phenomena that she regarded as mutually exclusive and opposed—she provided a wider context for understanding their relationships. For example, when Rand spoke of the valid opposition of selfishness versus altruism, she repudiated conventional definitions of both selfishness (which involved the brute, uncaring sacrifice of others to oneself) and altruism (which involved the caring, benevolent sacrifice of oneself to others).

For Rand, the alternative could not be characterized simply as an opposition between “selfishness” and “altruism.” She sought to define the credo for a “new concept of egoism”—the subtitle to her book, The Virtue of Selfishness (Rand 1964a)—and this led her to reject the conventional concept of selfishness, epitomized, perhaps, by the “master” morality of Nietzsche, and the self-sacrifice or “slave” morality advocated by mystical and collectivist thinkers, such as Saint Augustine and Auguste Comte. She thus gave voice to what Robert Heilbroner ([1981] 1987) tells us about the master-slave relationship, something recognized by Aristotle and Hegel alike:

The logical contradiction (or “opposite” or “negation”) of a Master is not a Slave, but a “non-Master,” which may or may not be a slave. But the relational opposite of a Master is indeed a Slave, for it is only by reference to this second “excluded” term that the first is defined. (6–8)

Thus, in The Fountainhead, Rand reveals how both “master” and “slave” morality require and imply one another. As she puts it: “A leash is only a rope with a noose at both ends” (Rand [1943] 1993, 661), alluding to the fact that masters and slaves are in a mutually destructive relationship of codependency. For Rand, the truly independent man is neither master nor slave.

In Atlas Shrugged, however, Rand’s focus shifts to the relationships among individuals as manifested within a larger social system, developing over time toward the inexorable rupture of coercive, collectivist statism and to the discovery of a new, humane society that recognizes the sociality of each individual as something that is not in conflict with, but a natural, harmonious by-product of, genuine individualism. In the process, Rand shows vividly that human beings can flourish socially only in a system that recognizes individual reason and individual rights.

As she wrote in her preparatory notes for Atlas Shrugged (initially titled “The Strike”), the novel had to focus on this wider cluster of relationships to fully illustrate the social implications of her commitment to reason and to the virtue of rational self-interest:

Now, it is this relation that must be the theme. Therefore, the personal becomes secondary. That is, the personal is necessary only to the extent needed to make the relationships clear. In The Fountainhead I showed that Roark moves the world—that the Keatings feed upon him and hate him for it, while the Tooheys are out consciously to destroy him. But the theme was Roark—not Roark’s relation to the world. Now it will be the relation. In other words, I must show in what concrete, specific way the world is moved by the creators. Exactly how do the second-handers live on the creators. Both in spiritual matters—and (most particularly) in concrete physical events. (Concentrate on the concrete, physical events—but don’t forget to keep in mind at all times how the physical proceeds from the spiritual.) (Rand, journal entry, 1 January 1945, quoted by Peikoff in Rand [1957] 1992, x)

This emphasis on analysis of the contextual totality as a cluster of relationships is crucial to Rand’s worldview. In the years after his 1968 break with Rand, Nathaniel Branden (1980) further clarified and extended this core notion—in opposition to those critics who saw the “atomistic” individual[3] at the center of classical liberal and libertarian thought:

There are a thousand respects in which we are not alone. . . . As human beings, we are linked to all other members of the human community. As living beings, we are linked to all other forms of life. As inhabitants of the universe, we are linked to everything that exists. We stand within an endless network of relationships. Separation and connectedness are polarities, with each entailing the other. (61)

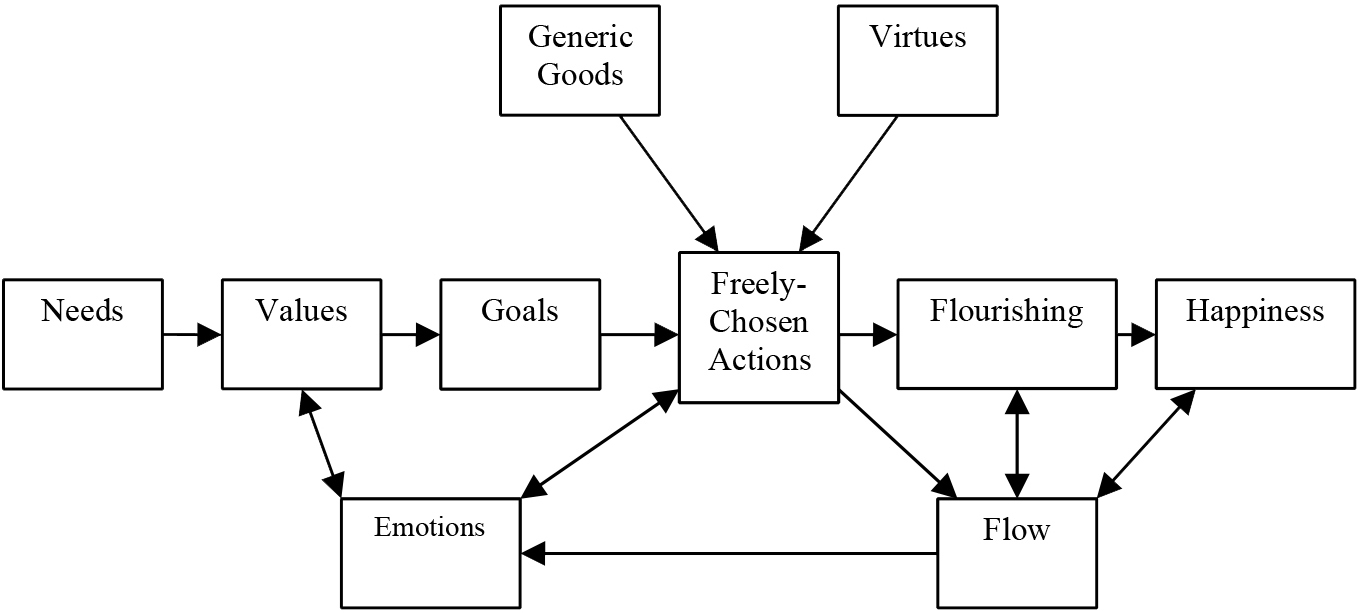

In Rand’s work and in the work of those influenced by her, atomism and disconnectedness fall by the wayside. The integration of mind and body, the essential connection between the spiritual and the material, is paramount. By the time Rand had authored Atlas Shrugged, she was emphasizing the need for shifts in vantage point and levels of generality—between the “Personal” and the “Social” (Rand, journal entry, 9 January 1954, in Harriman 1997, 653)—to elucidate different aspects of the objects under analysis. It is this kind of shift made explicit by Rand that inspired me to construct a model through which to display and interpret the structure, the dynamics, and especially the explanatory power of this form of wide-ranging contextual inquiry. This became the central guiding purpose of part III of Russian Radical.

Much like Hayek, Rand proclaimed herself a radical “in the proper sense of the word: ‘radical’ means ‘fundamental’” (“Conservatism: An Obituary,” in Rand 1967, 201). On this basis, Rand (1964b) wore the label as a term “of distinction . . . of honor, rather than something to hide or apologize for” (15).

I first proposed the Tri-Level Model of Social Relations in Russian Radical as a means of grasping the depth of Rand’s radical analysis of social problems (see Sciabarra [1995] 2013, 324–29, for example, which shows how this model is on display in Rand’s analysis of the problem of racism). But it was later in Total Freedom: Toward a Dialectical Libertarianism (Sciabarra 2000, 379–83), that I expanded on the model, elucidating the manner in which Rand shifts levels of generality and perspective, so as to grasp the systemic ways in which social problems develop over time. By consequence, only a comprehensive strategy can truly resolve social problems, given that their reciprocal causes and effects are to be found on each of those levels of generality that Rand’s approach makes transparent.

Though I provide below a diagrammatic presentation of the Tri-Level Model that focuses on Rand’s particular analysis (figure 1.1), I believe that this model can be helpful to any theorist working within a libertarian analytical framework. Indeed, libertarian theorists who disagree fundamentally with Rand’s premises and/or conclusions can separate the content of her analysis from the model and still use this model as a blueprint to develop their own dialectical-libertarian perspectives. The crucial point here is that despite my reconstruction of Rand’s approach as illustrative of the model’s usefulness, it can be employed by any theorist working in the classical liberal or libertarian traditions. It just compels such theorists to broaden their focus beyond strictly political and economic questions, because social relations of power (just as free social relations) are manifested on three distinct levels of generality, what I call “the Personal” (L1), “the Cultural” (L2), and “the Structural” (L3). These levels can only be abstracted and isolated for the purposes of analysis and can never be reified as wholes unto themselves. They are reciprocally related and are thus preconditions and effects of one another.

Source: Sciabarra [1995] 2000, 278; 2000, 380.

On Level 1 (L1), the Personal level of analysis, Rand analyzes social relations of power from the vantage point of individuals’ ethical, psychological, and “psycho-epistemological” practices—that is, the implicit (tacit) methods of awareness and other tacit factors that typically operate on a subconscious level of awareness (emotions, “sense of life,” and so forth), which often undermine self-responsibility and inculcate subservience or obedience to authority. On Level 2 (L2), the Cultural level of analysis, Rand analyzes social relations of power from the vantage point of linguistic, pedagogical, educational, aesthetic, and ideological factors that both reflect and bolster statist politics. On Level 3 (L3), the Structural level of analysis, Rand analyzes social relations of power from the vantage point of political and economic structures, processes, and institutions.

Each of these levels entails mutual implications; relations of power are both manifested in and perpetuated by personal, cultural, and structural dynamics. Most importantly, this tri-level model displays the broad outline of a dialectical libertarian strategy for social change, whether one accepts Rand’s specific applications of it or not. For in opposing the master-slave relationship in each of its manifestations, across each of the dimensions of the analytical model, Rand compels libertarians to aim for a nonexploitative society of independent equals who trade value for value. Indeed, by grouping the three levels into three distinct forms, we can illustrate how each level of generality provides us with a different analytical and strategic focus.[4]

In this combination, the Personal (L1) and the Structural (L3) levels are placed in the background of Rand’s analysis, and the preconditions and effects of culture (L2) are made the central, primary factor of consideration. This has the advantage of bringing into focus the dominant cultural traditions and tacit practices that help to perpetuate the overall system of statism, which Rand fundamentally opposed.

But an exclusive focus on those dominant traditions and practices tends to lessen our regard for people’s abilities to alter their psycho-epistemological or ethical habits (L1). Additionally, this focus minimizes the importance of the statist political and economic structures (L3) that both perpetuate and require specific cultural practices identified by Rand as “mystic,” “altruist,” and “collectivist,” a cultural base bolstered by dominant ideologies that celebrate the anti-rational, the necessity of self-sacrifice, and the primacy of the group.

Rand thought it was crucially important to pay attention to cultural context in the struggle for social change. For example, it’s one of the reasons she rejected wars dedicated to so-called “nation-building,” in which the United States had “sacrificed thousands of American lives, and billions of dollars, to protect a primitive people who never had freedom, do not seek it, and, apparently, do not want it” (Rand 1972, 66). Rand had opposed U.S. entry into World War I and World War II, but it was this more specific assertion that Rand made in her opposition to the wars in Korea and Vietnam. One could only imagine how she would have reacted to U.S. attempts to graft “democracy” onto the Middle East, a region dominated by tribalism and theocratic fanaticism, antithetical to those cultural preconditions necessary for the sustenance of a free society.

Another crucially important aspect of culture that Rand focused on was education and the pedagogical techniques that dominated educational institutions. By their ability to stunt individual cognitive development, undermine conceptual and linguistic clarity, and inculcate obedience to authority, few institutions were more powerful in creating a subservient population.

Though Rand placed strong emphasis on the influence of culture in sustaining social relations of power, she was not a cultural determinist. She did not grant that culture was the sole factor determining historical destiny. Cultural contextualism was key to understanding how power relations are perpetuated, and how free institutions might be nourished in the struggle for social change, but Rand unequivocally rejected cultural determinism and its reactionary implications.

In this combination, the Cultural (L2) and the Structural (L3) levels of analysis are placed in the background, and the preconditions and effects of the Personal (L1) are made the primary factor. This brings into focus the importance of those individual and interpersonal psycho-epistemological and ethical practices that perpetuate the irrational culture and politics that statism requires. It underscores Rand’s belief that individuals need to change themselves as a precondition of any attempt to change society. They need to practice rational virtues in pursuit of rational values—that is, rational actions in pursuit of rational goals. They need to engage in introspection, to articulate their thoughts, emotions, and actions, and to take responsibility for their own lives. Indeed, as Rand puts it, “anyone who fights for the future, lives in it today” (Rand 1975b, viii).

But an exclusive focus on the personal tends to shrink the importance of cultural and structural factors, which provide the context for, and have a powerful effect on, people’s abilities to be individuals. Certain cultural attitudes and practices are so deeply embedded in our lives, Rand suggests, that it is extremely difficult to call all of these into question at any given point. Moreover, Rand recognized that many individuals were put at a cognitive disadvantage, from elementary school through the institutions of higher learning, because of pedagogical practices that militated against individuals learning principles of efficient thinking, including proper methods of logical analysis, inductive reasoning, and contextual integration. (On these principles, see especially Branden 2017.) In essays such as “The Comprachicos” (in Rand 1975a, 187–239), she asserted that the educational system and its anticonceptual pedagogy tended to teach individuals how not to think, undermining their capacity to logically integrate and understand the real relations among things, events, and social problems, crippling their ability to act in a way that might radically transform for the better the society in which they live.

Likewise, certain political and economic realities often constrain and cripple our ability to act as individuals. Within statism, Rand argues, our ability to act as individuals is most constrained, since groups become the most important social unit in the shaping of public policy. This is not merely “identity politics” writ large: statism both requires and sustains tribalism of every sort. Or, as Rand put it, “the relationship is reciprocal”: Just as tribalism was a precondition of statism, so too was statism a reciprocally related cause of tribalism (“Racism” in Rand 1964a, 128).

Indeed, as statism grows, groups multiply along economic, ethnic, cultural, sexual, gender, ideological, and other lines, encompassing every aspect of human existence, reflecting a kind of “global balkanization” (“Global Balkanization” in Rand 1988, 123). Ultimately, what results is an internecine battle among warring pressure groups, leading to an “aristocracy of pull.” New Age–like thinkers who believe that all we need to do is “free ourselves first” and the rest will follow automatically, do not understand the organic unity of tribalism and statism. They often fall victim to Level 1 thinking, divorced from Levels 2 and 3.

The same dynamics are on display in the Randian literature on the nature of alienation, a subject that has been discussed primarily as a Level 1 issue by psychologists (see, for example, Stokols 1975, who views it as a “sequential-developmental” problem) and a Level 3 issue by Marxist theorists (see, for example, Ollman [1971] 1977, who views the problem as endemic to human life in capitalist society).[5] Psychologist Nathaniel Branden, who, after his 1968 break with Rand, would be dubbed “the ‘father’ of the self-esteem movement” (Campbell and Sciabarra 2016, 1), specifically addressed the subject in an essay (“Alienation”) that first appeared in installments in The Objectivist Newsletter. It was reprinted as a chapter in Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal (in Rand 1967, 270–96) and was later revised and expanded in one of Branden’s most important post-Randian works, The Disowned Self (Branden [1971] 1978, 207–37).

Branden’s discussion of modern alienation focuses not just on the vast cultural expanses of modern alienation (Level 2), but especially on Level 1 (personal) and Level 3 (political-economic) factors that are mutually reinforcing in their implications:

A free society, of course, cannot automatically guarantee the mental well-being of all its members. Freedom is not a sufficient condition to assure man’s proper fulfillment, but it is a necessary condition. And capitalism—laissez-faire capitalism—is the only system which provides that condition.

The problem of alienation is not metaphysical; it is not man’s natural fate, never to be escaped, like some sort of Original Sin; it is a disease. It is not the consequence of capitalism or industrialism or “bigness”—and it cannot be legislated out of existence by the abolition of property rights. The problem of alienation is psycho-epistemological; it pertains to how man chooses to use his own consciousness. It is the product of man’s revolt against thinking—which means: against reality.

If a man defaults on the responsibility of seeking knowledge, choosing values and setting goals—if this is the sphere he surrenders to the authority of others—how is he to escape the feeling that the universe is closed to him? It is. By his own choice. (in Rand 1967, 295)

In his later, revised version of this essay, which appeared as appendix B in The Disowned Self, Branden emphasizes the organic conjunction of the personal, cultural, and structural levels:

As to any sense of alienation forced on man by the social system in which he lives, it is not freedom but the lack of freedom—brought about by the rising tide of statism, by the expanding powers of the government and the increasing infringement of individual rights—that produces in man a sense of powerlessness and helplessness, the terrifying sense of being at the mercy of malevolent forces. (Branden [1971] 1978, 237; italics in text)

In this combination, the Personal (L1) and the Cultural (L2) levels of analysis are placed in the background, and the preconditions and effects of political and economic structures, institutions, and processes become the primary factors to consider. For Rand, this perspective has the advantage of bringing into focus the dominant political and economic practices that help to perpetuate statism, or the “New Fascism” as she called it (“The New Fascism: Rule by Consensus” in Rand 1967). Rand draws much from her knowledge of Austrian economics in explaining the destructiveness of statist policies. Among these practices, one sees: regulations, which often benefit the industries being regulated, blocking entry into whole fields of economic endeavor and giving impetus to the growth of coercive monopolies; financial manipulation through the Federal Reserve System and other institutions, which are the driving force of the boom-bust cycle; taxation, which often redistributes wealth to entrenched businesses slurping at the public trough—a chief component of what, today, is conventionally referred to as “crony capitalism”; an expanding welfare state bureaucracy that keeps people in an endless cycle of poverty and dependency; and all the other prohibitions, laws, and guns that constrain us.

These constraints have global significance since a country’s statist domestic policy often extends into the sphere of foreign policy, providing the context for “pull-peddling” interventionism abroad (Sciabarra [1995] 2015, 315–23), the growth of the national security state, and ultimately, the pretext for wars (whether they be of the cold or hot variety, including those that grow out of protectionist or neomercantilist practices).

But an exclusive focus on these dominant political practices tends to shrink the importance of, and need for, individuals to alter their ethical or psycho-epistemological habits (Level 1). Such a focus also tends to obscure the importance of culture, which has a powerful effect on the kinds of politics and economics that are practiced (Level 2).

One of the most important criticisms that Rand levels against “anarcho-libertarians” is that they reify a Level 3 analysis, as if an attack on the state is all that is needed to liberate humanity. Such an attack is futile, in Rand’s view, in the absence of those personal and cultural practices that are essential to the sustenance of political freedom.

By tracing the implications of the tri-level model, we highlight the relational links that Rand sees among the various factors in society. Indeed, this is how she put the tools of a dialectical analysis to work. Each of her commentaries on the social problems of the day reveals the complex interrelationships among personal, cultural, and structural components of those problems. She subjects virtually every social problem to the same multidimensional analysis, rejecting all one-sided resolutions as context-dropping—that is, as partial and incomplete—if they do not identify important reciprocal relations or fundamental factors that generate more salient, but less basic manifestations. As a “radical for capitalism,” Rand (1961, 25) writes: “Intellectual freedom cannot exist without political freedom; political freedom cannot exist without economic freedom; a free mind and a free market are corollaries.” Rand (1962) argues further that: “A change in a country’s political ideas has to be preceded by a change in its cultural trends; a cultural movement is the necessary precondition of a political movement” (1).

Just as relations of power operate within psychological, psycho-epistemological, ethical, cultural, political, and economic dimensions, so too the struggle for freedom and individualism necessarily takes place within a certain constellation of psychological, psycho-epistemological, ethical, cultural, and structural factors.

This emphasis on the contextual totality is so central to Rand’s approach that Leonard Peikoff, one of Rand’s foremost orthodox interpreters, has argued that, methodologically, Hegel was right to say: “The True . . . is the Whole” (Peikoff 1991, 4). Peikoff argues that Rand’s systematized approach embodies this methodological principle. But Peikoff rightly adds that even though one could be correct about broad fundamental principles of method, one might also be operating with erroneous foundational premises, an improper approach to validation, faulty induction, incorrect identifications of historical data, or quasi-mystical conceptions of what the concretes are—such as Leibnizian monads, Hegelian Ideas, or the stages of economic production outlined in Marxian historical materialism. Hence, defending a dialectical libertarianism requires more than just a methodological commitment to understanding the analytical integrity of the whole.

The third and concluding book in my “Dialectics and Liberty Trilogy” was Total Freedom: Toward a Dialectical Libertarianism, published in 2000 by Pennsylvania State University Press. Although each of these works can be read on its own terms, each remains an extension of the other, and together, the significance of each work becomes more apparent. In particular, Total Freedom attempts to answer many of the outstanding questions from the first two books in the trilogy.

In part I of Total Freedom, I offer a rereading of the history of dialectical thinking, a redefinition of dialectics as an indispensable tool for any defense of human liberty and a critique of those aspects of modern libertarianism that are decidedly undialectical and, hence, dangerously utopian in their implications.

I often refer to dialectics most concisely as “the art of context-keeping.” In part I of Total Freedom, however, I develop a much more refined definition of dialectics, viewing it as a species of the genus “methodological orientations” and comparing it with other such orientations (specifically, strict atomism, dualism, monism, and strict organicism). Because human beings are not omniscient, because none of us can see the “whole” as if from a “synoptic,” god-like perspective, it is only through a process of selective abstraction that we are able to piece together a more integrated understanding of the phenomenon before us—including an understanding of its antecedent conditions, interrelationships, and tendencies. In social theory, the object of our inquiry is society: social relations, institutions, and processes. Society is not some ineffable organism; it is a complex nexus of interrelated institutions and processes, of volitionally conscious, purposeful, interacting individuals—and the unintended consequences they generate. Understanding the complexities at work within any given society is a prerequisite for changing it.

In my reconstruction of the history of dialectics, which takes up the first three chapters of the book, I begin with the ancient Greeks. It is no accident that even Hegel, Marx, and Lenin celebrated Aristotle as the father of dialectics, the man whom Hegel ([1840] 1995, 130) himself called “the fountainhead” of dialectical inquiry. In works such as the Topics—the very first theoretical treatise on dialectics—Aristotle presented numerous techniques by which one might gain a more complete picture of an issue by varying one’s “point of view.” The Topics serves as a grand discussion of how shifts in one’s perspective can reveal different things about the objects of our inquiry and about the perspectives from which those objects are viewed. But examples of the use of dialectical techniques abound throughout the Aristotelian corpus.

In rereading the history of dialectical thinking, from the ancients to the postmodernists, I place special emphasis on the unheralded dialectical techniques used by classical liberal and libertarian thinkers such as Herbert Spencer, Carl Menger, Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek, Ayn Rand, Nathaniel Branden, and Murray Rothbard. My finding of dialectical elements extends as well to contemporary libertarians as diverse as Roger E. Bissell, Douglas Den Uyl, Douglas Rasmussen, and Edward W. Younkins (who work within a neo-Aristotelian framework); Deirdre McCloskey (who has emphasized the importance of the rhetorical dimension in defense of liberty); Hans-Hermann Hoppe, G. B. Madison, and Stephan Kinsella (who offer variations on a dialogical or “estoppel” framework, as Kinsella calls it); Gerald O’Driscoll, Mario Rizzo, Don Lavoie, Peter Boettke, Steven Horwitz, David Prychitko, and Robert Higgs (each of whom has contributed to an Austrian resurgence with an emphasis on dynamics, drawing from schools of thought as different as Public Choice, the New Institutional Economics, and Hermeneutics); Jason Lee Byas, Kevin Carson, Gary Chartier, Billy Christmas, Nathan Goodman, and Roderick T. Long (who have been associated with left-libertarianism or left-market-anarchism); and scholars such as Robert L. Campbell, Troy Camplin, and John T. Welsh, whose work encompasses fields as diverse as psychology, evolutionary biology, aesthetics, political theory, and social science methodology. We are fortunate to be able to feature the contributions of many of these contemporary writers in this volume.

While many of these thinkers have long exhibited important aspects of a dialectical approach in their work, I certainly cannot claim credit for having fundamentally influenced the vast majority of these scholars. Rather, I view my own work as having made explicit the unacknowledged or implicit dialectical elements to be found in the work of classical liberal thinkers and many of my contemporaries in the libertarian intellectual tradition. Nevertheless, to the extent that my explicit articulation of a dialectical libertarian research program has influenced my contemporaries, I cannot claim any credit or responsibility for the diverse directions that it has taken over the past two decades. In this regard, I have always adopted a hermeneutical approach to my own work (and in my analysis of the work of others). As I wrote in Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical:

As W. W. Bartley argues, the affirmation of a theory involves many logical implications that are not immediately apparent to the original theorist. In Bartley’s words, “The informative content of any idea includes an infinity of unforeseeable non-trivial statements.” The creation of mathematics, for instance, “generates problems that are wholly independent of the intentions of its creators” [Bartley, “Knowledge is a product not fully known to its producer,” in Leube and Zlabinger 1984, 27].

I have adopted a similarly hermeneutical approach. The principles of this scholarly technique were sketched by Paul Ricoeur in his classic essay, “The Model of the Text” [see Dallmayr and McCarthy 1977, 316–34]. Ricoeur maintains that a text is detached from its author and develops consequences of its own. In so doing, it transcends its relevance to its initial situation and addresses an indefinite range of possible readers. Hence, the text must be understood not only in terms of the author’s context but also in the context of the multiple interpretations that emerge during its subsequent history.

The central lesson of this hermeneutical approach is that no concept or delineated theory—such as dialectics or the possibility of a dialectical libertarianism—is frozen in time. This makes a dialectical libertarianism all the more significant as a theoretical and strategic vision; it is not a sclerotic deduction of the implications of fixed axioms, but a living, viable research program that seeks to grasp the complexities of a wider systemic context over time—a context that might nourish or undermine the achievement of human freedom.

And, so, the question must be asked: Just how fruitful can any “dialectical libertarianism” be if thinkers united under that umbrella are as different from one another, in some respects, as Marx was from Mises? In truth, it is almost impossible not to find some form of dialectical analysis in the work of any thinker. No thinker can be totally nondialectical, just as no thinker can be totally illogical, for, as Aristotle himself noted, we are bound to find some dialectical and logical sensibility in virtually any person who thinks, “since the truth seems to be like the proverbial door, which no one can fail to hit” (Metaphysics 2.1.993b5–6 in Aristotle 1984, 1570)—or, in colloquial parlance: even a broken clock is correct twice a day!

I think the important issue is this: If the ideas of such thinkers differ fundamentally in content, whom can we identify as more faithful to a dialectical approach, and hence more radical in their social analysis? This is not a trivial question, because, as I outline in the first book of my “Dialectics and Liberty” trilogy, Marx, Hayek, and Utopia (Sciabarra 1995), dialectical thinking is identifiable with radical social theory, whereas nondialectical thinking leads to its opposite: utopian social theory. There is a fundamental distinction between dialectical, radical thinking and nondialectical, utopian thinking. As I write:

the radical is that which seeks to get to the root of social problems, building the realm of the possible out of the conditions that exist. By contrast, the utopian is, by definition, the impossible (the word, strictly translated, means, “no place”). . . . [U]topians internalize an abstract, exaggerated sense of human possibility, aiming to create new social formations based upon a pretense of knowledge. In their blueprints for the ideal society, utopians presuppose that people can master all the sophisticated complexities of social life. Even when their social and ethical ends are decidedly progressive, utopians often rely on reactionary means. They manifest an inherent bias toward the statist construction of alternative institutions in their attempts to practically implement their rationalist abstractions. (Sciabarra 1995, 1–2)

In the most dialectical aspects of his critique, Karl Marx recognized the pitfalls of utopian thinking, but because of fundamental flaws in his epistemology and in the premises of his social theory, he ultimately succumbed to those very pitfalls in his projection of a future communist society, whose utopian tenets can result in nothing but dystopian consequences. I discuss those flaws at length in both Marx, Hayek, and Utopia and Total Freedom: Toward a Dialectical Libertarianism.

Marx provides us with a prime example of how a thinker can exemplify certain strengths of a dialectical analysis of social problems, while still failing to provide valid conclusions. Logical consistency and integrated thinking do not stand if they are built upon false premises. It is not without significance that Rand had named her very first Objectivist Newsletter column “Check Your Premises,” for without valid premises grounded in the facts of reality, whole systems of thought come crashing down regardless of the logical or dialectical dexterity of those who construct them.

Two different thinkers can look at the same (or similar) facts of reality and grasp some of the same issues at work in understanding a particular social problem and yet, because of differences in their theoretical premises, may arrive at fundamentally opposed solutions to those problems. For example, Marx’s understanding of the boom-bust cycle shows some remarkable similarities to the valid theories put forth by Ludwig von Mises and F. A. Hayek, fathers of the modern Austrian school of economics (Sciabarra 1995, 76–79). Marx shares with his Austrian rivals an understanding of the political character of the business cycle, viewing the state and central banking as the fulcrum of the credit system and, hence, the source of the inflationary boom and its inexorable bust. But Marx views this as historically progressive, because it hastens the collapse of capitalism and the movement toward socialization of the means of production. By contrast, Mises saw the state-banking sector as a retrogressive institution grafted onto market relations, a product not of free-market “capitalism,” but of political economy in the fullest sense of the phrase (see especially Sciabarra 2000, 291–95). Mises argued that the dissolution of the state-banking nexus and the establishment of a full gold standard would end the boom-bust cycle along with its chaotic calculational and redistributive effects, clearing the way for the globally liberating processes of market forces.

I devote part II of Total Freedom to a full exegesis of the thought of Murray Rothbard, as a way of illustrating how thinkers can exhibit both dialectical and nondialectical elements in their work, with conflicting radical and utopian implications.[6] At his most dialectical, Rothbard, following the Misesian approach, analyzes the subject of class dynamics and structural crisis from many vantage points and on several levels of generality (Sciabarra 2000, 267–307). Indeed, the very notion of a “state-banking nexus,” in Rothbard’s approach, is inherently dialectical, because it is both a precondition and effect of the institutions in their fundamental relationship, which defines the nature of both the modern state and the modern banking system. It makes possible the emergence of class conflict, domestic and foreign interventionism, and the boom-bust cycle. For Rothbard, the state cannot be what it is in the absence of its support of and/or from the banking system, and the banking system cannot be what it is in the absence of the state.

And yet, there is a fundamentally dualistic conception that animates Rothbard’s quest “for a new liberty” (Rothbard 1978)—specifically his view of the state and the market as dualistic adversaries, leading him to advocate the monistic absorption of the state’s functions into market activities (his notion of “anarcho-capitalism”). This doesn’t necessarily mean that a nondualistic anarchism is impossible (see, for example, Johnson 2008). But Rothbard’s focus is primarily a political one, a Structural focus, which does not pay enough attention to those Personal and Cultural prerequisites for the nurturing of a free society. In later years, he became more sensitive to those prerequisites for a libertarian social order; but in my view, his strategy for “Liberty Plus” (Rothbard 1990) raises more questions than it answers (Sciabarra 2000, 355–62).

In the final analysis, dialectical libertarianism forms the basis of a broad research program, within which there may be much theoretical diversity and varying strategic implications. The project seems daunting, for the invitation to large-scale theorizing might give the impression that one must analyze everything before one can change anything. But this specter of “analysis paralysis” is as much of an example of the “synoptic delusion” fallacy as is the notion of central planning. What is required is a more fully developed critique of the system that generates the social problems in our midst—and a corresponding vision for social change that resolves these problems at their root, in all their personal, cultural, and structural manifestations. A genuinely radical project beckons, one that integrates the explanatory power of libertarian social theory and the context-keeping orientation of dialectical method.

Aristotle. 1984. The Complete Works of Aristotle. Volume Two. The revised Oxford translation. Edited by Jonathan Barnes. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Branden, Barbara. 2017. Think as if Your Life Depends on It: Principles of Efficient Thinking and Other Lectures. Foreword by Chris Matthew Sciabarra. Transcriber’s introduction by Roger E. Bissell. Print version published by CreateSpace. Kindle edition also available.

Branden, Nathaniel. [1971] 1978. The Disowned Self . New York: Bantam.

———. 1980. The Psychology of Romantic Love . New York: Bantam.

Burns, Jennifer. 2009. Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right. New York: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, Robert L. and Chris Matthew Sciabarra. 2016. Prologue to symposium: Nathaniel Branden: His work and legacy. The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies 16, nos. 1–2 (December): 1–14.

Camplin, Troy. 2017. After the avant-gardes. Review of After the Avant-Gardes: Reflections on the Future of the Fine Arts. Edited by Elizabeth Millan. The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies 17, no. 1 (July): 68–83.

Dallmayr, Fred R. and Thomas A. McCarthy, eds. 1977. Understanding and Social Inquiry. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Harriman, David, ed. 1997. Journals of Ayn Rand. Foreword by Leonard Peikoff. New York: Dutton.

Hayek, F. A. [1944] 1994. The Road to Serfdom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

———, ed. 1954. Capitalism and the Historians. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

———. [1956] 1980. The dilemma of specialization. In Studies in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics. By F. A. Hayek. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 122–32.

———. 1973. Law, Legislation, and Liberty—Volume I: Rules and Order. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hegel, G. W. F. [1840] 1995. Lectures on the History of Philosophy: Volume 2—Plato and the Platonists. Translated by E. S. Haldane. Introduction by Frederick C. Beiser. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, Bison Book Edition.

Heilbroner, Robert. [1981] 1987. The dialectical approach to philosophy. In Machan 1987, 2–18.

Heller, Anne C. 2009. Ayn Rand and the World She Made. New York: Doubleday / Nan A. Talese.

Johnson, Charles. 2008. Liberty, equality, solidarity: Toward a dialectical anarchism. In Long and Machan, 155–88.

Leube, Kurt R. and Albert H. Zlabinger, eds. 1984. The Political Economy of Freedom: Essays in Honor of F. A. Hayek. Munich: Philosophia Verlag.

Long, Roderick T. and Tibor R. Machan, eds. 2008. Anarchism/Minarchism: Is Government Part of a Free Country? Abingdon, Oxon, UK: Ashgate.

Machan, Tibor R., ed. 1987. The Main Debate: Communism versus Capitalism. New York: Random House.

Mises, Ludwig von. [1949] 1963. Human Action: A Treatise on Economics. Chicago: Henry Regnery.

Murray, Charles. 1995. The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life. New York: Free Press.

Ollman, Bertell. [1971] 1977. Alienation: Marx’s Conception of Man in Capitalist Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Peikoff, Leonard. 1991. Objectivism: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand. New York: Dutton.

Rand, Ayn. [1943] 1993. The Fountainhead. 50th anniversary edition. With a new afterword by Leonard Peikoff. New York: Signet.

———. 1961. For the New Intellectual. New York: New American Library.

———. 1962. Check your premises: Choose your issues. The Objectivist Newsletter 1, no. 1 (January): 1, 4.

———. [1962] 1967. Conservatism: An obituary. In Rand 1967, 192–201.

———. 1964a. The Virtue of Selfishness: A New Concept of Egoism. New York: New American Library.

———. 1964b. Alvin Toffler’s Playboy interview with Ayn Rand: A candid conversation with the fountainhead of “Objectivism.” The Objectivist (March). Reprint.

———. 1967. Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal. New York: New American Library.

———. 1972. The Shanghai gesture, part III. The Ayn Rand Letter 1, no. 15 (24 April): 65–68.

———. 1975a. The New Left: The Anti-Industrial Revolution. Rev. ed. New York: New American Library.

———. 1975b. The Romantic Manifesto: A Philosophy of Literature. 2nd rev. edition. New York: New American Library.

———. 1982. Philosophy: Who Needs It. New York: New American Library.

———. 1988. The Voice of Reason: Essays in Objectivist Thought. Edited and with additional essays by Leonard Peikoff. New York: New American Library.

Rothbard, Murray N. 1978. For a New Liberty. Rev. ed. New York: Collier Books.

———. 1990. Why paleo? Rothbard-Rockwell Report 1, no. 2.

Sciabarra, Chris Matthew. 1987. The crisis of libertarian dualism. Critical Review 1, no. 4 (Fall): 86–99.

———. 1988. Toward a Radical Critique of Utopianism: Dialectics and Dualism in the Works of Friedrich Hayek, Murray Rothbard, and Karl Marx. Ph.D. diss. New York University.

———. 1995. Marx, Hayek, and Utopia. Albany: State University of New York Press.

———. [1995] 2013. Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical. 2nd ed. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

———. 2000. Total Freedom: Toward a Dialectical Libertarianism. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

———. 2017. Reply to the critics of Russian Radical 2.0: The dialectical Rand. The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies 17, no. 2 (December): 321–57.

Stokols, Daniel. 1975. Toward a psychological theory of alienation. Psychological Review 82, no. 1: 26–44.

To be fair, even though economists such as Mises and Rothbard have used the Robinson Crusoe metaphor in describing what Mises ([1949] 1963, 194) called the “autistic exchange” of the “isolated hunter who kills an animal for his own consumption,” the heterodox approach of the Austrian tradition focuses its prime attention on the dynamics of real-world factors, epitomized in its emphasis on time, uncertainty, and imperfect knowledge—and the function of the price structure in a market process of rivalrous competition that drives entrepreneurial discovery and innovation.

There is evidence in the Branden Biographical Interviews that Rand did use the term “dialectical” in a nonpejorative sense as a way of describing her approach—in contrast to the extreme rationalism that she identified in the thought of architect Frank Lloyd Wright (Interview #13). Contrary to my own transcription of that interview, it appears, however, that Rand’s use of the word reflected correspondence with Martin Lean, a professor of philosophy at Brooklyn College. (This is according to Gregory Salmieri, who revealed this in personal correspondence with me.) Here was my initial transcription of the relevant section of the interview, where Rand contrasted her approach with that of Wright:

his approach to ideas was: the Truth with a capital T, and you know what that means. It’s not quite my approach. In other words, he would not be what we call “dialectical.” . . . In other words, he would not be a precise definer or intellectual philosophical conversationalist; he would be the emotional philosophical genius who would talk about the meaning of Life, with a capital L. . . . (Branden Biographical Interview #13, 26 February 1961; transcription and emphasis mine)

Having examined a transcript from the Ayn Rand Archives, Salmieri tells me that Rand actually states: “In other words, he would not be what Lean would call ‘dialectical.’” Regardless, it is clear that Rand, at the very least, referenced the word from Lean who saw it as an apt description of her approach in that specific context. See Sciabarra 2017, 338–39 (some of the material in the current section being derived from this essay). Similarly, there is evidence that she did identify her politics as “libertarian” in the Old Right sense (Burns 2009, 48–49), even though she came to reject libertarianism in later years, especially in the aftermath of her encounters with the Circle Bastiat, led by Murray Rothbard (182–84). Also see Heller 2009, 295–303.

So wedded was Rand to the concept of mind-body integration that she rejected the very notion of the “atomistic” as an “anti-euphemism,” a way of denigrating individualism by identifying it with a “scattered, broken up, disintegrated” conception of human being. See “How to Read (and Not to Write)” in Rand 1988, 131.

These three levels of generality can accommodate other aspects of social research that are beyond the scope of this chapter. For example, this tri-level model is very relevant for those who have argued, along the lines of Charles Murray (1994), about the relative impact of genetic, biological, and environmental factors shaping the cognitive and emotional capacities of individuals or certain groups of individuals—and how this might affect social relations of power. Even if one accepts Murray’s highly contentious thesis, which, he argues, bears on “intelligence and class structure in American life,” it is still necessary to subject the evidence he offers (or any evidence to the contrary) to the rigor demanded by this tri-level analysis.

To take another example from our own volume, see Troy Camplin’s essay “Aesthetics, Ritual, Property, and Fish: A Dialectical Approach to the Evolutionary Foundations of Property,” which examines the impact of genetics, deep evolutionary psychology, and ritual in the genesis of private property. Camplin offers a truly broad, complex, and highly dialectical context to consider, but it is one that the proposed tri-level model easily incorporates insofar as it enables us to grasp the implications of the analysis for each of the levels of generality that the model highlights. The point here is that the tri-level model does not offer canned answers; it offers, instead, different lenses by which to draw out the full implications of the evidentiary support for any research that bears on social relations of power—or of freedom.

Special thanks to Ryan Neugebauer for alerting me to the essay by Stokals (1975). I should also take this opportunity to thank Ryan, as well as Nick Manley, and my co-editors, Roger E. Bissell and Edward W. Younkins, for their comments on an earlier draft of this chapter. The usual caveats apply.

Part II of Total Freedom was also drawn from a portion of my doctoral dissertation (Sciabarra 1988, 79–299).

Edward W. Younkins

Toward a Synthesis of Traditions and Disciplines

Philosophy provides the conceptual framework necessary to understand man’s behavior.[1] To survive a person must perceive the world, comprehend it, and act upon it. To survive and flourish, a man must recognize that nature has its own imperatives. He needs to have viable, sound, and proper conceptions of man’s nature, knowledge, values, and action. He must recognize that there is a natural law that derives from the nature of man and the world and that is discoverable through the use of reason.

By combining elements found in the writings of Aristotle, Austrian economists, the Objectivist philosopher Ayn Rand, neo-Aristotelian, classical liberal philosophers of human flourishing, and those from other disciplines, we can reframe the argument for a free society into a consistent, reality-based whole whose explanatory power is greater than the sum of its parts. In other words, the Austrian, value-free, praxeological defense of capitalism and the moral and political arguments of Aristotle, Rand, the neo-Aristotelians, and others can be brought together in a libertarian synthesis of great promise, a powerful argument for a free society in which individuals have the opportunity to flourish and to be happy. In particular, it will be argued that Aristotelian and neo-Aristotelian theories of morality and human flourishing are compatible with Objectivist teachings about the nature of reality and man’s distinguishing characteristics of reason and free will, and with Austrian ideas about value theory, decision making, action, and social cooperation.

Neo-Aristotelian classical liberals have provided the model for the approach taken in this chapter, modifying aspects of Aristotle’s political and economic philosophy and combining them with classical liberal and Austrian political and economic thought. Although these thinkers do not agree on every detail, they tend to include, and agree upon, most of the following features in their writings: metaphysical and epistemological realism; an identifiable human nature (i.e., essentialism), the moral and rational nature of man; the existence and importance of rationality, practical reason, free will, and free choice; agent causality; a natural teleology of human flourishing or self-perfection; the possibility of ethical knowledge; a eudaimonistic theory of virtue ethics; individualism; natural law and natural rights; the natural sociality of man with the implied importance of civil society and subsidiarity; a political theory emphasizing freedom, pluralism, diversity, and the limited nature of the state; and praxeology as a tool for deriving objective economic principles and the logical implications of such principles. A conceptual framework will be presented that integrates these ideas along with those of a number of contemporary philosophers, economists, political scientists, positive psychologists, and others.

A dialectical approach is useful in advancing our knowledge of freedom and flourishing. Dialectics may be viewed as a method of analysis, a model of inquiry, a meta-methodological orientation or meta-theoretical foundation that emphasizes context-sensitivity in its approach to any object of study. An Aristotelian dialectical approach attempts to grasp the full context and to understand the whole through differential vantage points and levels of generality. Stressing the totality of systems and dynamic connections, the dialectical thinker makes every possible effort to see interconnections between and among seemingly disparate branches of knowledge. This is done by first shifting viewpoints on any object of study in order to illuminate different aspects of it and then combining the various perspectives in order to gain a comprehensive understanding of the full context of the object of study. This approach allows us to recognize the dynamic interrelationships between the personal, political, historical, psychological, ethical, cultural, economic, and so on (Sciabarra 2000).

Because no field is totally independent of any other field, there are really no discrete branches of knowledge, only cognition in which subjects are separated for purposes of study. Examining an object of study from a variety of alternative contexts, vantage points, and disciplinary areas can aid the investigation of reality. In a complex world, there is the need to bring together insights and methodologies from a variety of disciplines, which can mutually enrich and inspire one another. Dialectics calls for an inclusive, transdisciplinary approach to the study of freedom, flourishing, and happiness. An open-system realism combines approaches and disciplines and promotes critical exchange, mutual engagement, pluralism, and methodological toleration. Scholars are needed whose systematic project is to integrate disciplines and to discover the unity of intellectual frameworks beyond disciplinary perspectives. Context-keeping individuals are needed to investigate from a variety of perspectives and at different levels of generality to make connections among seemingly disparate disciplines in order to illustrate the unity of knowledge. Synthesists are needed to build links and collaborative unity across artificially disjointed disciplines. Philosophers, economists, political scientists, psychologists, sociologists, cultural anthropologists, and neuroscientists are at the forefront of modern research on freedom, flourishing, and happiness. They need to work together on an integrative yet open model. Such a study of well-being requires attention to personal, demographic, economic, political, cultural, historical, psychological, biological, and other factors.

Because of the nature of reality, it is impossible to totally separate subjects when analyzing a phenomenon. Disciplinary boundaries are blurred and permeable and mere artifacts of scholarship, and do not reflect actual divisions in reality. Boundaries blur, fields intersect and overlap, and connections are amplified as integration becomes the goal of education. Of course, for purposes of specialization, it is essential to keep in mind the context and vantage point from which an object is being studied; but in the end, we need to reintegrate the results of such study with the rest of our total knowledge of reality. Although we do have to subdivide reality in order to study an aspect of it, we need to reintegrate at the end of our analysis with the added new knowledge. Abstraction requires integration, and differentiation necessitates a consideration of unity. Because a paradigm’s consistency with reality is all that matters, it is legitimate to take a selective approach with respect to existing philosophical positions (e.g., Aristotelianism, the school of Austrian economics, and Objectivism), to extract what is true from their writings, and to use it as the basis for a better integration and a deeper understanding. Such is the case in the study of human flourishing and happiness and the type of society that would make these possible.

What follows here is a brief attempt, relying heavily on logic, dialectics, and common sense, to formulate ideas about freedom and flourishing, and to relate them logically to other ideas and to the facts of reality. Because the rules of logic are determined by the facts of reality, logic is in a sense not only epistemological but also ontological. Furthermore, even though there are differences between these ideas and the identity of the things that they are about, the ideas themselves are derived from and about reality. However, because my concern as a system-builder is with truth as an integrated whole, this inquiry does not extend beyond a systemic level. It provides an outline of the essentials of a worldview, leaving it to philosophers, economists, and others to fill in the details and to evaluate, critique, revise, refine, and extend my proposed systematic framework.

A proper political and economic philosophy must be based on the nature of man and the universe. Our goal is to have a paradigm that appeals to and reflects reality as an independent ontological order—a paradigm in which the views of reality, human nature, knowledge, values, action, and society make up an integrated whole. Such a paradigm will help people to understand the world and to survive and flourish in it. Once this knowledge is gained, we can then ascertain the role the state should have. Because necessary prescriptions are embedded in the nature of things and are discoverable through observation, logic, and a rational epistemology, what is required is philosophical realism in the secular natural law tradition. Natural law can provide man with a framework of the nature of human society and with general and universal principles (see d’Entreves 1951; Finnis 1980; Gierke 1957) that will permit the construction of the best political regime.

A proper philosophy must appeal to the objective nature of human beings and other entities in the world. There is a world of objective reality that exists, and it has a determinate nature that is intelligible. Because reality establishes the conditions for objectivity (see Buchanan 1962; Gilson 1986; Miller 1995; Pols 1992) and will not yield to permit a person’s subjective desires, realism is a necessary, instrumental means for a person’s success in the world.

There is a human nature, and because each individual has a specific identity as a human being, we can say that there are particular things and actions that are appropriate to him and for him. It is man’s nature to be a metaphysically unique self,[2] volitionally conscious, rational, and purposive. Possessing reason and free will, each individual has the capacity and responsibility to discern and use proper means to attain his truly valuable ends, to actualize his potential to be a flourishing, individual human being and to be morally efficacious. One’s entire life can be viewed as a project or overall goal that is subject to continual evaluation. A person has the responsibility to discover his individual strengths and virtues and what is good for himself through a process of moral development, to choose wisely his aims and aspirations within the changing circumstances of his life, and to perfect himself by fulfilling the potentialities that make him who he is.

Morality is an essential functional component of one’s existence as an individual human being. Moral knowledge is possible and can be derived from the facts of reality including human nature. Possessing rationality and free will, a person needs a proper moral code to aid him in making objective decisions and in acting on those decisions in his efforts to attain his true self-interest. Morality and self-interest are inextricably interrelated. Morality is concerned with rationally determining what best contributes to a person’s own flourishing and happiness.

An individual’s flourishing is teleological, consisting in the fulfillment of his unique set of potentialities to be a mature human being. Each person has an innate, unchosen potentiality for his mature state along with the obligation to attempt to actualize that potentiality. Each person is responsible to discern and to live according to his daimon (i.e., true self), which includes his aptitudes, talents, and so on. This involves a process of progressive development, unfolding, or actualization in which a man attains goals that are in some way inherent in his nature as an individual human being. What constitutes a person’s daimon at a given point in time is a function of his endowments, circumstances, latent powers, interests, talents, and his history of choices, actions, and accomplishments. We could say that the fulfillment of one’s daimon is not static or fixed. An individual uses his practical rationality to assess himself and to work on his life in accordance with the objective standard of his flourishing as a singular human person. He can increase his generative potential to attain his own flourishing. A person is able to critique what he has done in the past and can change what he does with respect to the future development of his potentialities. Possessing free will, a man can adjust his actions in response to feedback that he has received.

Flourishing is a successful state of life, and happiness is a positive state of consciousness that flows from, or accompanies, a flourishing life. The legitimate function of every human person is to live capably, excellently, and happily. This involves an ethic of aspiration toward one’s objective well-being that is actively attained and maintained. A person should aspire to what is best for him, taking into account his given potentialities, abilities, and interests. Limits for self-fulfillment are set by reality including the type of being that we are and our individual characteristics.

In their work on second wave positive psychology, Lomas and Ivtzan (2016) have pointed

out the fundamentally dialectical nature of well-being. Working from a Hegelian dialectical

perspective, they explain that flourishing involves a complex and dynamic interplay

of positive and negative experiences. A flourishing life consists of plural and oftentimes

conflicting values. There is a dynamic interplay or tension between interacting elements

or forces. They have identified five key dichotomies: optimism vs. pessimism, self-esteem

vs. humility, freedom vs. restriction, forgiveness vs. anger, and happiness vs. sadness.

They have identified the following principles: (1) The principle of appraisal, which

states that it can be difficult to categorize specific phenomena as either positive

or negative; (2) The principle of co-

valence, which says that many experiences involve a complex, intertwined blend of

positive and negative elements; and (3) The principle of complementarity, which states

that flourishing itself involves an intellectual dialectic, balance, and harmonization

between positive and negative aspects of living (i.e., a dynamic harmonization of

dichotomous states). Although individuals should strive to maximize the positive in

their lives, it is true that we are all faced with certain, negative, involuntary

aspects of life, and that there is virtue and merit to dealing with, and attempting

to overcome, those negative aspects.