Getting great candidates does not happen without significant effort. The CEOs of billion-dollar companies that we interviewed for this book recognize recruitment as one of their most important jobs. They consider themselves chief recruiting officers and expect all of their managers to view their jobs the same way.

These successful executives don’t allow recruiting to become a one-time event, or something they have to do only every now and then. They are always sourcing, always on the lookout for new talent, always identifying the who before a new hire is really needed.

The traditional hiring process looks something like this. A vacancy opens up in a manager’s division, and the manager panics. He has no idea how he is going to fill the spot, so he calls HR and begs for help. HR asks him for a job description, which he copies from an old one he finds and submits to the HR team to post.

Predictably, three months go by without much traction until, getting desperate, the manager pushes the HR team to source more people. Finally, HR presents a few candidates to the manager, and since nobody in the firm knows anything about these people, they subject the candidates to multiple forms of voodoo hiring methods with the hope of making a good decision. Months later, the manager fills the position with one of these unknowns.

Take a moment and think about how passive such an approach is. It relies on finding people in “talent pools” at particular points of need. Yet we all know that talent pools grow stagnant. Like tidal pools far from the ocean’s edge, talent pools rarely contain the most vital and energetic candidates. In fact, these traditional talent sources are so overworked that most of the people left in them are not the ones you would want to hire.

Little wonder that the most frequent question we receive in workshops is “How do I source A Players?” Clearly managers at all levels are frustrated by what they perceive as the lack of innovation on this topic.

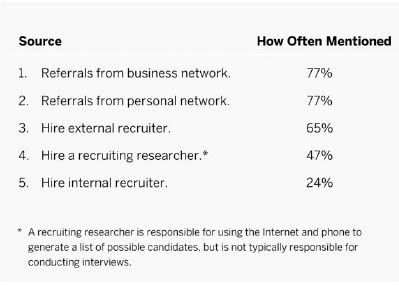

We observe that many managers source candidates by placing advertisements in one form or another. The overwhelming evidence from our field interviews is that ads are a good way to generate a tidal wave of resumes, but a lousy way to generate the right flow of candidates. Other methods include using recruiters and recruiting researchers, although success depends heavily on the quality of the actual recruiter assigned to your search.

Of all the ways to source candidates, the number one method is to ask for referrals from your personal and professional networks. This approach may feel scary and timeconsuming, but it is the single most effective way to find potential A Players.

This is an instance where innovation matters far less than process and discipline.

REFERRALS FROM YOUR PROFESSIONAL AND PERSONAL NETWORKS

The industry leaders we interviewed didn’t speak with one voice on every topic, but on the subject of sourcing new talent through referrals they were nearly unanimous. Without any prompting from us, a full 77 percent of them cited referrals as their top technique for generating a flow of the right candidates for their businesses. Yet among average managers it is the least often practiced approach to sourcing.

Take Patrick Ryan, who grew Aon Corporation from a start-up in 1964 to a $13 billion company. “I am not really smarter than the next guy,” he told us. “There are lots of smart people in business. I guess the one thing that I have done over the years that is different from most people is that I am constantly on the hunt for talented people to bring into my company.

“I set a goal of personally recruiting thirty people a year to Aon. And I ask my managers to do the same. We are constantly asking people we know to introduce us to the talented people they know.”

Ryan’s approach is among the easiest we have seen. Whenever he meets somebody new, he asks this simple, powerful question: “Who are the most talented people you know that I should hire?” Talented people know talented people, and they’re almost always glad to pass along one another’s names. Ryan captures those names on a list, and he makes a point of calling a few new people from his list every week. Then he stays in touch with those who seem to have the most promise.

You can almost certainly identify ten extremely talented people off the top of your head. Calling your list of ten and asking Patrick Ryan’s simple question—“Who are the most talented people you know that I should hire?”—can easily generate another fifty to one hundred names. Keep doing this, and in no time you will have moved into many other networks and enriched your personal talent pool with real ability.

But don’t stop there. Bring your broader business contacts in on the hunt, too. Ask your customers for the names of the most talented salespeople who call on them. Ask your business partners who they think are the most effective business developers. Do the same with your suppliers to identify their strongest purchasing agents. Join professional organizations and ask the people you meet through events. People you interact with every day are the most powerful sources of talent you will ever find.

The concept extends into your personal and social networks. We suspect that one of the first questions you get asked when you meet someone new is “What do you do?” Next time you answer that question (probably in the next week or two if our experience is any guide), follow up with “Say, now that I have told you what I do, who are the most talented people you know who could be a good fit for my company?” Do that, and you will turn a common social question into a sourcing opportunity.

After years of asking for referrals and personally recruiting people into his company, Patrick Ryan has become a master talent spotter. Not only has he personally sourced many of the executives who lead Aon today, but he spotted and landed his ultimate successor as well.

“I’ve always believed that senior hiring should be targeted hiring,” he said. “I thought it was time for us to find my successor. It is not something to really put off. You should take a lot of time in doing that.”

Ryan let the board search committee do its job, but he also offered names from his own network, including Gregory Case, whom Ryan had first met when Case was at McKinsey, the strategy consulting firm.

“He was only forty-two at the time. He had run a big division of McKinsey. People would say he did not have CEO experience, corporate experience, or public corporate experience. I thought he could overcome those because not only was he smart and hardworking, but also he was going to lead, have vision, and take the group along with him. What’s more, Greg brought talented people with him.”

All this didn’t happen overnight. As he did with others in the talent pool he had built through referrals, Ryan nurtured his relationship with Case over a period of many years before finally convincing Case to succeed him as CEO.

Ryan did the same thing when he hired his new general counsel, Cameron Findlay, whom he had met when Findlay was a lawyer at Sidley Austin, one of the largest law firms in the United States.

“He was number one in his Harvard Law School class. He had a great academic background and had a very successful background as a lawyer. I maintained a relationship with him while he was in the George W. Bush administration. I figured it was time to see him since that administration’s first term was winding down. I told him I really wanted him to join Aon. I was the first person to call Cam, and he joined us.”

What sets Patrick Ryan apart from so many other executives is how he actively built his network through referrals, then followed up with high-potential candidates to maintain the relationship. He kept his sourcing network alive and constantly renewed. And because he was disciplined about doing so, he didn’t have to go looking when a position opened up at Aon, including his own job. Ryan was already right in the midst of a flow of great candidates.

REFERRALS FROM EMPLOYEES

As valuable as outside referrals are, in-house ones often provide better-targeted sourcing. After all, who knows your needs and culture better than the people who are already working for you? Yet while this is far from a blinding insight, we’re constantly amazed at how few managers actually take the time to ask their employees for help.

Selim Bassoul, the chairman and CEO of Middleby Corporation, told us that employee referrals have been an incredible source of A Players as he doubled his business over the last five years.

“Our employees became our number-one recruiting technique,” he said. “We told the employees, ‘If you spot somebody like us, at a customer, at a supplier, or at a competitor, we want to hire them.’ That became very successful. People would say there is a great person there; let’s go after them. Employees referred 85 percent of our new hires!”

Paul Tudor Jones, president and founder of Tudor Investment Corporation, also leverages referrals from his existing employees. “It takes A Players to know A Players,” he reasons with good cause. “Our success rate is 60 percent higher for people who are referred by somebody else in our firm.”

At ghSMART, we’ve made in-house referrals a key part not only of our staffing policies but also of promotions. Principals have to source three candidates who can pass a phone screen by our CEO to earn eligibility for a promotion to partner. The payoff, as far as we’re concerned, has been little short of amazing. In the past two years, 80 percent of our new hires have come from team member referrals.

Our approach is highly disciplined—we think we should practice what we preach—but virtually any size organization can achieve much the same effect by building internal sourcing into their employee scorecards. Try including something along the lines of “Source [number] A Player candidates per year,” then reward the effort by providing a financial or other incentive such as extra vacation time for those who achieve and exceed the goal. Like us, you will quickly find yourself fishing in a greatly enriched pond.

Maybe the greatest benefit of in-house sourcing, though, is how it alters the mind-set throughout an enterprise. By turning employees into talent spotters, everyone starts viewing the business through a who lens, not just a what one. And why shouldn’t they? Ultimately, the organization’s fortunes are going to rise or fall on the ability to bring the best people on board. Hold employees accountable for sourcing people through their networks, and everyone will benefit when talent flows into the business.

DEPUTIZING FRIENDS OF THE FIRM

Back in the Wild West days when the marshal was getting ready to head out into the backcountry to hunt down a pack of villains, he would round up a handful of the town’s leading citizens, deputize them as temporary law officers, and off the posse would go, riding into the sunset. Law enforcement has grown considerably more sophisticated in the years since, but the idea of extending the reach of your search through “deputizing” some of the most influential people in your network is still a good one.

One company we know offers recruiting bonuses to its deputies—rewards of up to $5,000 if the company hires somebody the deputy sourced, depending on the level of the hire. Other companies provide incentives to their deputies and turn them into unofficial recruiters with gift certificates, iPods, and other valuable items.

BSMB, a multibillion-dollar buyout fund based in New York, has purposefully built an extensive network of deputies to help it source people for its portfolio. John Howard, the company’s CEO, described the network to us this way: “We have a group of people who are affiliated with us to whom we can reach out at any time. We have senior executives with all kinds of expertise, so we always have people to call when we need to find A Players in specific industries or to solve certain problems.”

In this case, Howard said, the incentive is both particular to the business and quite inventive: “They get to invest in our funds without fees.” With BSMB funds typically generating 30 percent or greater annual returns, deputies are quick to return Howard’s calls.

Many early-stage companies set up an advisory board to serve the same purpose as BSMB’s deputies. These advisors neither involve themselves with governance of the company nor take on fiduciary responsibility. Their reason for being is to offer advice and make introductions. In return, the company rewards them with a small amount of stock or modest cash compensation.

WHI Capital Partners has built both a network and multiple advisory boards to source talent for the companies in its portfolio. As Eric Cohen, a managing partner at the firm, told us, “To date, we have not used any recruiters to hire the five CEOs and ten other high-level executives in our portfolio. We do it a few ways. We bring people in through a trusted network. For example, we are partnered with an organization of two hundred CEOs. We can rely on their recommendations sometimes. We have also built strong boards and advisory boards at our portfolio companies as well as for WHI Capital. We’ve been able to find the person just going through a pretty extensive networking process.

“It’s kind of like dating. If you are introduced to someone randomly in a bar, there is a chance it might work out, but you are more likely to have a higher success rate if you have a friend or family member introduce you.”

Deputizing friends of the firm will create new, accelerated sources of talent, but you still need to pay attention to process, and you have to be disciplined. Make sure that the deputies are reporting in on a regular basis, and whatever incentive you choose, check and double-check that it’s sufficient so that busy people will participate.

Remember, you want your recommendations to come from A Players. As the old playground taunt goes, it takes one to know one.

HIRING EXTERNAL RECRUITERS

Recruiters remain a key source for executive talent, but they can do only so much if you don’t expose them to the inner culture and workings of your business. Think of recruiters much the way you would think of a doctor or a financial advisor. The more you keep them in the dark about who you are, what’s wrong, and what you really need, the less effective they will be.

As the SVP of human resources for Allied Waste, the $6 billion waste management company, Ed Evans has worked with many recruiters throughout his career and has experienced a wide variety of performance levels.

“You have to treat them like partners. Give them enough of a peek under the kimono so they really understand who you are as a firm and as a person. Recruiters who do not understand who you are will be counterproductive.”

In fact, great recruiters are unlikely to accept an assignment from you unless they have an opportunity to get that view. Even if they do sign on, they might force you to explore different candidates and perspectives as a way for them to peek under the kimono.

That’s part of what the best of the breed do. They educate you about the market for talent, much as a real-estate agent might take you around to multiple houses to gauge your tastes. Being open at the outset, sharing your scorecard, and doing everything else you can to bring an outside recruiter inside both streamlines the process and enhances the results.

HIRING RECRUITING RESEARCHERS

External recruiting firms often contract with recruiting researchers to explore a market, identify sources of talent, and feed names back to the recruiting firm. You can do the same by hiring researchers to augment your sourcing efforts. Researchers won’t conduct interviews themselves. Instead, they’ll identify names for your internal recruiting team or managers to pursue.

The benefits of this concept are obvious. For minimal cost, companies get a pipeline that taps into a rich source of talent. Even better, hiring the researchers on a contract basis helps maintain a variable cost structure.

The downside with researchers is that they won’t qualify candidates as thoroughly as you might like. That vetting process falls on the internal recruiters or the hiring manager directly.

An emphasis on quantity over quality can also clog the hiring process with warm bodies. One company we know was so overwhelmed with the inbound flow of candidates that it finally asked its researchers to screen candidates a little more thoroughly. This reduced the flow of people but increased their value.

You can help tailor the flow of candidates to your needs by taking time at the front end to orient recruiting researchers to your culture, business needs, and even management style and preferences. Unlike external executive recruiters, researchers aren’t likely to become your new best friend, but the more they know going in, the more you will get out of them at the end.

SOURCING SYSTEMS

Sourcing talent through these proven practices is easy. The challenge is less a matter of knowing what to do than of putting a system in place to manage the process—and having the discipline to follow through.

When the crunch is on, you and your hiring team are likely to be meeting people all day long, every day. Many of them could be A Players for some role in your company. If you’ve brought in recruiters and recruiting researchers, they will be bringing still more people to your attention. How do you capture all these names and, more important, follow up with them to build a relationship?

One executive we know uses index cards, and he is methodical in the extreme. Along with their name, he writes down a few snippets he learned, such as a spouse’s name or a hobby or a topic of discussion. He routinely revisits these cards and follows up with the people on them. Those who know him marvel at how well he remembers details about their lives.

If you are used to operating in a more high-tech environment, spreadsheets have the added advantage of letting you sort by name and date. Another executive we know generates a weekly call list by loading a follow-up date against every name in his spreadsheet.

Many big companies use off-the-shelf tracking systems to sort and filter job candidates and applicants. We are not in the business of recommending particular vendors. Suffice it to say that a good system will enable all of the employees in your business to contribute names and other useful information to the company’s database of potential A Player candidates.

Don’t be lulled into inattention by the technology, though. The most high-tech tracking system in the world won’t do you any good if you don’t use it on a systematic basis. The final step in the sourcing process, the one that matters more than anything else you can do, is scheduling thirty minutes on your calendar every week to identify and nurture A Players. A standing meeting on Monday or Friday will keep you honest by forcing you to call the top talent on your radar screen.

Here’s a best practice that puts that thirty minutes to work. Close the door to your office or go into a conference room. Pull out your list of potential A Players and sort the list by priority. Now, start making calls until you have at least one live conversation.

The conversation does not have to be long. We frequently begin with something simple like, “Sue recommended that you and I connect. I understand you are great at what you do. I am always on the lookout for talented people and would love the chance to get to know you. Even if you are perfectly content in your current job, I’d love to introduce myself and hear about your career interests.”

Most people will be thrilled to chat. Done well, you will find you can connect with forty or more new people per year. That’s a quick way to build an impressive network.

One more thing. When you are done with the call, assuming you were even moderately impressed with what you heard, be sure to ask the key follow-up question: “Now that you know a little about me, who are the most talented people you know who might be a good fit for my company?”

Hiring needs always ebb and flow with the business, but simple systems and disciplines—and simple questions such as the one just shown—will enable your sourcing network to grow exponentially over time.

CASE STUDY: FINDING THE RIGHT CEO

Bank One board members James Crown and John Hall put all these sourcing principles to work when they recruited Jamie Dimon to lead the financial conglomerate, widely regarded as one of the most successful CEO recruitments in recent history.

A little background first. Bank One could trace its roots back to 1868 in Columbus, Ohio, but it was decidedly a creation of the merger mania of the 1980s. In 1988, the bank acquired First Chicago/NBD for $28.9 billion, moved its headquarters to Chicago, and set about trying to merge the two organizations at the corporate headquarters level. The practice, though, was not always perfect.

“In the summer of 1999,” Crown told us, “we had serious problems at one of our credit card businesses, First USA. They told us they were going to have a serious earnings shortfall and a significant increase in loan losses. Moreover, the forecast trends were for things to get worse.

“We were clearly headed for trouble, as First USA had been an important source of earnings. No one had confidence that we understood how bad things might be, what we should do, or who would take control of the situation.

“This aggravated an environment that was already tense; neither the board nor the senior management group was truly integrated and working as a team. There had been disagreements about strategy, personnel, and compensation. The stress of impending losses and an eroding balance sheet just made matters worse.

“When John McCoy, the chairman and CEO, left, a treaty was worked out to search for a new CEO to lead the bank. The chairman of the nominating committee and I went on a mission starting in December 1999 to find ourselves a new CEO.”

The search committee began by creating a basic scorecard—perhaps too basic, Crown said. “We established criteria, but they seemed quite generic: experience, strong general management skills, knowledge of regulation, ability to deal with shareholders and a lot of employees. You write all of these things down because it is a wish list, but you are not really sure what all of these mean.”

Next, the Bank One board began searching for a recruiter who could help it find the right person given the complexities of the situation. They finally settled on Andrea Redmond at Russell Reynolds.

Redmond began by working extensively with the board to refine its generic scorecard into something actionable.

“The search consultant has to speak with every board member and feed what she hears back to the whole board to confirm what she heard. You don’t want to get down to the wire and realize that board members are on the wrong page. With Bank One, we knew that we needed financial services and we needed leadership—execution style. They were not integrated.”

Next, Redmond began sourcing candidates and evaluating additional candidates that the board knew from its networks. Then she put James Crown and John Hall, the chairman of the nominating committee, to work.

“John and I traveled to many locations,” Crown recalled. “We met people who were not even interested. We took no as an opening bid. We explored two issues with the candidates: (1) the status of the bank and what they thought was needed, and (2) other candidate names—to learn about people we might not have considered or to source reference checks on the people on our list.”

That search process led them finally to Jamie Dimon, who recalled vividly his first meeting with Crown and Hall.

“Jim was a very decent human being. John was a first-class mensch. I told them, ‘You don’t know me very well. This is like a marriage. I’m going to tell you who I am and what I’m like, and if you don’t think I’m the right person, you don’t want me.’”

Dimon showed even greater openness in his first session with Andrea Redmond.

“When I first met Jamie, what I was most impressed by was how blatantly candid he was,” she recalled. “I’ll never forget this. When I am busy and stressed, I can be really abrupt. We sit down. I said, trying to be sensitive, ‘So tell me a little bit about your leaving Citigroup.’ He said, ‘You know what? I was fired.’ I was stunned because nobody has ever said that to me. Nobody in fifteen years has come right out and said that. They say something else, like strategic differences, yadda, yadda, yadda. My head flew back. Finally somebody was being totally honest.”

Dimon had been a longtime protégé of Sandy Weill at Citigroup, but conflicts arose during their final years together that resulted in his termination. Long viewed as a rising star on Wall Street, Dimon was given many offers.

Still, his forthrightness went a long way toward convincing Redmond, Crown, Hall, and ultimately the Bank One board that Dimon was the right person for the job, and events have borne out that decision time and again. Under Dimon’s leadership, Bank One doubled in value and went on to merge with JPMorgan Chase in July 2004, at which point Dimon became president and chief operating officer and subsequently CEO and president of JPMorgan Chase at the end of 2005, and chairman of the board a year later.

HOW TO SOURCE

1. REFERRALS FROM YOUR PROFESSIONAL AND PERSONAL NETWORKS. Create a list of the ten most talented people you know and commit to speaking with at least one of them per week for the next ten weeks. At the end of each conversation, ask, “Who are the most talented people you know?” Continue to build your list and continue to talk with at least one person per week.

2. REFERRALS FROM YOUR EMPLOYEES. Add sourcing as an outcome on every scorecard for your team. For example, “Source five A Players per year who pass our phone screen.” Encourage your employees to ask people in their networks, “Who are the most talented people you know whom we should hire?” Offer a referral bonus.

3. DEPUTIZING FRIENDS OF THE FIRM. Consider offering a referral bounty to select friends of the firm. It could be as inexpensive as a gift certificate or as expensive as a significant cash bonus.

4. HIRING RECRUITERS. Use the method described in this book to identity and hire A Player recruiters. Build a scorecard for your recruiting needs, and hold the recruiters you hire accountable for the items on that scorecard. Invest time to ensure the recruiters understand your business and culture.

5. HIRING RESEARCHERS. Identify recruiting researchers whom you can hire on contract, using a scorecard to specify your requirements. Ensure they understand your business and culture.

6. SOURCING SYSTEMS. Create a system that (1) captures the names and contact information on everybody you source and (2) schedules weekly time on your calendar to follow up. Your solution can be as simple as a spreadsheet or as complex as a candidate tracking system integrated with your calendar.

Why was this search so successful? Part of it was the collaborative working relationship Redmond established with the board. Just as important was the commitment Hall and Crown made to the search process.

“John Hall committed 100 percent of his time to the search,” Redmond told us. “He saw eight to twelve candidates. He was very involved and very responsive. When you have a chairman that is willing to make it that kind of priority, you can make it happen.”

That commitment, in turn, played a major role in convincing Dimon to sign on to what he knew would be an extremely challenging task. “The board made me feel that I was a high-priority candidate. It takes a lot of trust to take a job like this. The board’s personal high involvement level and their flexibility on the issues that were important to me were some of the reasons I took the job.”

The larger lessons to be taken away here are the ones we’ve been stressing throughout this chapter. Take the time to hire and educate the right recruiter. Make sure she understands your needs and culture, and don’t miss the opportunity to learn from her. Source from everywhere you can, including the board’s network. And stay engaged: If you don’t own the process, no one will. Talent is what you need. Focus and commitment will get you there.