CHAPTER 1

Starting to think about a care home

In 2007, a Lancashire County Council research survey1 returned statistics that showed the top concern for people over sixty-five to be the fear of losing independence. The research was conducted among people all aged over forty-five, showing that where worries about money most affected people up to fifty-five, after that anxiety focused on loss of independence.

Sixty-two per cent were afraid of not being able to get out and about; 52 per cent said they did not want to become dependent on others; and 48 per cent were afraid of having to leave their homes.

Of the 1,700 people surveyed, 69 per cent cited being able to stay in their own homes as the most important aspect for a happy life in old age.

The only thing that surprises me is that the percentage was not even higher.

“Going into care” is a matter of dread for many, many elderly or infirm people, or others whose needs makes it hard for them to be safe living in their own homes.

A neighbour of mine, in her eighties, recently made the transition from living alone in her large semi-detached villa to residential care. She was desperately lonely, she had had many falls, and she could not go out alone or get upstairs. She had two sons, one living abroad but making frequent trips home to see her, the other doing all he could to put together a care package that would support her adequately at home. She was loved, she had friends, but the time came when she needed someone on hand round the clock. It was very evident that she could no longer manage, and yet, in those difficult weeks and months as her family monitored her situation, assessing what could be done to get things right for her, a friend and frequent visitor to her home whispered to me, eyes big with drama and voice laden with emotion, “She don’t want her sons to know how bad she is, because she’s frightened they’ll have her put away!”

To say that “going into care” has a bad press would be an understatement of monumental inadequacy. This book is about what we might do to make that transition easier: the acknowledgment of how much is lost, the rebuilding of a sense of self, the issues that should be considered in helping people to accept dependency without losing the ability to be happy.

Our task will be to look steadily at how much we ask of people when they must give up their homes for the last time. So there will be much said about trauma, sadness, and bereavement.

We will take a very careful look at what every one of us reading these pages might do to make ready for the time when “we” morph into “them” and become in our own turn the frail, the incontinent, the bent, slow souls with the ulcerated legs, going along slowly with the aid of a walking frame to the postbox at the corner. What attitudes, what habits of mind and life, could be the gift of today to tomorrow?

But right here at the outset, before we work through the difficult issues to be addressed and steadily faced, let’s not forget that – however much they might have dreaded making the transition – lots and lots of people have a really nice time in residential care.

The right place

The key to a successful outcome is, of course, finding the right place. That achieved, it can be the beginning of a new lease of life not only for the individual concerned but for all those who bore the responsibility for their care at home as well.

A friend of mine whose mother had Alzheimer’s disease talked to me about the impossibility of giving her mother the care she needed – precisely because she was her mother. A mother–daughter relationship is often hierarchical – mother’s wishes are to be respected, her preferences observed; her daughter is to treat her with due deference. Mother gives advice and often laments aloud the failure of the younger generation to do anything (from table manners to international banking) properly. When the time comes that her daughter must tell her in no uncertain terms to change her knickers, and insists on going through the fridge or tracking down that very iffy smell emanating from the wardrobe, the balance of the relationship is badly threatened. Let battle commence!

When my friend’s mother “went into care”, the focus was all on the safety and supervision of the mother. The bonus never even considered beforehand was that, in the short time left before her mother descended into infirmity, the two of them had their friendship back again. My friend became the welcome visitor bringing special treats and the promise of outings, the person who stayed to chat and share a cup of tea, instead of the evil witch who humiliated her own mother by ferreting out soiled linen and mouldy corned beef.

When they “go into care”, people who dared not venture much past their kitchen doorstep, whose gardens resemble nothing so much as virgin rainforest with a strong emphasis on buddleia, can once again sit out in the June sunshine and enjoy a cup of tea surrounded by well-kept roses.

People whose leisure options extended to television or sitting quietly find Scrabble partners, discussion groups, in-house communion services, and a visiting library when they “go into care”.

Having someone to wash your hair, the possibility of eating freshly cooked vegetables, and someone else to lug that heavy vacuum cleaner around can all be a tremendous relief.

With the ascendency of family-friendly software from innovators like Nintendo, some residential care homes are able to put their televisions to good use in offering regular Wii Fit sessions to encourage residents to set their own levels in staying supple and active, and connected in to the developments of modern leisure pursuits.

Such a reality is nothing to dread!

It’s important to make the distinction between a transition that is difficult because it is a move from something desirable to something undesirable, and something that is a positive move but is challenging because thresholds and transitions always are. So let’s be clear that we are not here joining forces with my neighbour’s wild-eyed friend, shaking our heads in mute disgust that people must be “put away”. We are saying that the practical, good, helpful, life-enhancing option of residential care, even while it offers so much to individuals and their families, still requires courage, still asks a great deal, and still calls for imaginative and sensitive pastoral support.

When it comes to searching out the right residential care home, the variables and possibilities are almost endless. The choice is a very individual one. Even what might at first seem to be obviously limiting factors – money, for example – may not necessarily be so. Some residential accommodation of a very rough-and-ready, cheap-and-cheerful ambience might suit some people better than a rarefied and plush or clinical atmosphere of a more expensive home offering “better” facilities.

Some residential care homes offer a programme of opportunities to make friends and keep active – music and movement classes, singalongs and coach trips – whereas others may offer a calm and dignified atmosphere with a beautiful garden to enjoy. One prospective resident may prioritize the privacy of an en suite bathroom, whereas another may be content with shared facilities or a commode.

It is a matter of taking the time to consider what really matters to the person who is going to live there. It is also worth enquiring among people who work locally as care assistants. Very often, among elderly populations the reputation of a care home can relate to what it used to be like ten years ago, when you need to know what it is like today. What do the agency nurses and carers think?

“How on earth do I find out that?” you may be wondering. Care assistants are not a well-paid workforce. I should think many of them keep an eye on Freecycle, the website where unwanted household items are given away free. A question posted on the café section noticeboard might draw a response. Many faith communities take the care of their elderly seriously, so enquiring at a church or mosque or gurdwara might give some helpful feedback.

“Is the food nice?” is not the sort of question that will tell you what you need to know. Nor is “Are the staff kind?” It depends what kind of food you like, and the staff may be kind to your friend’s mother, but not necessarily to yours. Your friend’s mother might be a real poppet whereas yours may be an absolute witch. But having a look at the way the rooms are organized and what facilities for receiving visitors are offered, enquiring about moving and lifting policies, the programme of in-service training given for care assistants as well as nurses, the ratio of staff to residents, and the levels of MRSA infection in the place might yield a little more information.

Inspection reports giving very helpful information are published online, but even then some important details can be missed. Only two out of three stars were given to one of the most loving care homes I know – a place where the manager/proprietor instigated the wonderful custom of having the funerals of residents take place there within the sitting room of the home. The coffin is brought in and placed on trestles in the conservatory, against a backdrop of the beautiful garden beyond; the organist brings her keyboard, and all the residents and staff are able to attend. No one is left out because they are too poorly or on duty that day – everyone is included. The residents in this care home were too frail in health for it to be practical to consider taking any significant number of them out to the funeral, and some of the care staff would inevitably have to stay behind to look after those who could not go. When you consider how integral a part of that community of staff and residents each resident becomes, it begins to feel very fractured and sad that most funerals of residents could normally include only a small delegation of one or two staff members to represent the home, and usually none of the other residents. A care home that would pioneer so sensitive and imaginative an initiative has my attention immediately.

A visiting inspector may not ask the questions that would turn up such information, so inspection reports are most useful in conjunction with personal acquaintance or recommendation from a trusted friend. Having said this, published inspection reports provide an immensely helpful resource for anyone beginning to investigate the residential care possibilities in their local area, and may include information about where and how to obtain a care assessment and help with finance.

In the appendix at the back of the book, you will find a list of useful websites and organizations offering this sort of practical help, information, and advice.

When the time has come to leave one’s own home and find residential care accommodation, there may be a sense of relief: struggling on with insufficient help can leave us feeling desperate, vulnerable, and afraid. Even so, all change brings challenges, and it is wise to take the time to think through the emotional impact of such big changes, however welcome and necessary they may be. It is important, too, to consider and establish what are the hopes, priorities, and expectations of the person “going into care”, doing a reality check on those, and forming a vision for a way forward that is both feasible and desirable.

Grief at what is lost

Over a number of years employed as a church pastor, meeting with people who were dealing with life’s big issues – birth, marriage, sickness, death, family trouble – I have often seen people shed tears and express grief and sorrow, but not very often in nursing homes. This seems odd to me. When it is plain to see how fiercely people cling to their homes, memories, and possessions, would they not weep to leave them?

If I were a widow living in a little bungalow that my husband (God rest his soul) had built with his own hands, and where I had planted the garden, with an old tabby cat lying by the ashes of the fire, and the paintings and sculptures of my children displayed on the walls and shelves, I should weep to leave that place. If I were leaving the home where the plaster bore the pencil marks of the heights of my children as they grew, the place where my youngest was born one stormy June morning, the kitchen where the family gathered every day to eat the nourishing one-pot meals where a tiny bit of meat was augmented by beans and carrots and potatoes and barley until it fed us all, I would weep inconsolably. If I were that widow saying goodbye to my Norfolk chair and my Orkney chair (the one that came from my mother) and the kelims I picked up at the flea market, and the olive tree I’d been growing in a pot on the terrace for twenty-four years, and the china tea-service that came from my great-grandmother, and the canteen of cutlery that my husband’s parents had for a wedding present, I would weep and weep as my heart broke over many months.

I remember once seeing a mother go to the rescue of her little girl who had fallen and grazed her knee. The child was horrified by the trickle of blood, and as she comforted her, the mother said, “It’s good for it to bleed, darling; it flushes away the dirt.”

And so it is with tears. Tears are good.

Yet many people feel uncomfortable when someone is weeping, alarmed at the sense of disintegration, of things going wrong, and at the sense of responsibility that comes in the company of someone so vulnerable.

I remember very vividly watching a small group of mourners arrive at an elderly woman’s funeral. The husband of the deceased woman was in the centre of the group, clearly on the verge of tears. He had lost his beloved companion of over sixty years. His sister, standing close to him, was urging him not to cry: “Come along, Jack! Be a man! Keep your chin up!” It was their way – to weep in a public place would have felt deeply embarrassing to that family – but surely it should be acceptable to shed tears at the funeral of your wife?

Our tears are often held back, to be expressed in times of privacy. If we can help it, we do not weep on the railway station, in the library, in the hotel foyer. We weep in the solitude of our own room at home, in the arms of those we love and trust, in the protective space of the wide shore as we sit looking out at the ocean.

It is comforting, healing, or supportive, to people who have lost their homes and everything in them, to allow them to feel they can cry. People ought to be allowed to shed their tears when they have lost everything. There should be enough sense of privacy and there should be someone they can trust and confide in to make this possible.

Who will there be, in a care home, to sit with newcomers who need to shed tears at the loss and sadness of leaving the familiarity of home? Maybe a member of the family, who has come with the new resident to help them settle in. But some people are even more embarrassed by expression of emotion in their own family than with strangers. Maybe one of the care staff will have time to sit with the new resident, talk quietly together, allow some the emotion of what must be processed to overflow. But care staff are often pressed for time, occupied with residents’ meals, helping them to the bathroom or to wash and get into bed. If the resident–staff ratio is high, it may be that the only time the care staff have to listen to residents is when they are helping them on the toilet. And although, in general, care staff are likely to be more comfortable with the expression of what is usually private – emotion, bodily functions – than the general public may be, some members of staff will be more at ease with people who are overwhelmed with sorrow than others. A chaplain or trained volunteer may have a very helpful role to play here, having both the understanding and the time to spend specifically on what is happening in a person’s inner world. There may also be a key worker assigned to the new resident, who will build a particular relationship and take time to listen and to understand.

Even at such momentous times of change, there will be some making the transition to living in care accommodation who have come to terms with the tearing pain of loss. Some will have gradually downsized their possessions in a wise, strategic manner, maybe making a series of house moves from the large family home to the retirement bungalow to the warden flat and now finally to a residential care home or nursing home room. Some will have spent a long time in hospital considering what to do for the best – going through the options, making arrangements – and will have gone through a process of accepting the necessity for change. Some will be simply in shock – bewildered, not knowing how to be or who to be in these unfamiliar surroundings, with the soothing routines of home all entirely evaporated.

Some new residents may have come unwillingly to this new place and may be frightened or belligerently defensive. They will need extra reassurance as they come to terms with the changes in their lives – and, if they are noisy or disorientated and confused, it may be a time when extra support is needed for all the residents, who may find the newcomer distressing or alarming.

If the care staff, chaplains, and volunteers in our care homes, and the relatives of those who must leave their own home, have the maturity and confidence within themselves to consider and behold the emotions and responses of those who leave their independence behind – even when they cannot fix it – they will be agents of healing and reassurance.

To hear the stories of times now gone also helps. Even when someone has left the familiar setting of their own home for a room that presents an entirely different kind of environment, memories have vitality and power to recreate a sense of personal history and identity.

Martha was like a statue, calm and stoical and pale: it was hard to know what she thought or what she had heard, or even if her wits were entirely functioning. But one day as I sat beside her and took time to chat, I realized that in fact she was simply far away most of the time. As she talked about the dairy farm, about taking the cows for milking across the hill where a wide and busy road now hummed with traffic night and day, about primrosing in the spring along the hedgerows of Three Oaks and Westfield, she began to come alive. As she told me how her brother had helped her and Tom to buy the cottage when the chance came – but they had paid the money back, yes, every penny– and as she remembered the winter they had walked to chapel along the tops of the hedges because the snow was so deep, I saw the only animation on Martha’s face I had ever seen. She needed to relive the past to live at all.

In helping people to make the transition required when they leave behind the home that was the repository of so much experience and memory, the chaplain, visitor, or care assistant who has the time to listen may offer more than they will ever know: the chance once again to touch what was held so dear.

Regret for what might have been

It is not always recognized that when we can no longer live in our own homes, we are losing not only what we had but also the chance for what we didn’t have.

Perversely, the loss of what we never had can bring a far deeper grief than the loss of what we have had.

You can observe this in the lives of adult children mourning the death of a parent who did not love them. They suffer a double grief: the loss of the person who has died and the loss of hope for a breakthrough or reconciliation one day.

You can see it also in people struggling with one of the great challenges of middle age: the acceptance of mediocrity – the recognition that I will always be an assistant teacher, never a head; that I may be the star of the amateur dramatic society, but I don’t have quite what it takes to go professional; that I will never make a million; that when fifty years of working life have gone by, I will have paid off the mortgage on this budget villa with its rather inadequate garden – and that will be my life’s achievement.

The small half of what we lose is what we had; the greater half is the loss of the things that might have been.

This loss is exacerbated by our tendency to assume that what might have been would inevitably have been good. So, when a nun talks about choosing a celibate life in community, she may fantasize that in making this choice she gave up the chance to have a husband who loved her, a family of children, and a home of her own. I never met a nun who imagined that what she gave up was a cramped and vulnerable life of lonely singledom (never met the right person somehow), or a marriage soured by the sadness and frustration of infertility, or the terror and grind of living with a violent man who drank too much and sexually abused his children. It was never that sort of life the nun imagined she had given up – more the cottage with roses round the door.

Similarly, the man who is disabled by a stroke in his forties and can no longer manage at home is unlikely to say to himself, “Actually, I would never have amounted to much anyway – I’m lucky to get my bills paid here, because I certainly never managed to cover them on the wages I could earn.”

No. The loss of what might have been is massive, as big as our imagination; you could say it is the losing of our dreams. And although the great future may have existed only in our imagination, the loss nonetheless is very real.

Although mourning for what might have been is a human inevitability, it is not an occupation that feeds the soul. The most helpful place to start any journey of the soul will always be “what is real, now”. What could be, should be, or might be true is likely to include a few water bombs of disappointment.

To honour and touch gently the real journey of the real past, to open one’s hands and permit what might have been to go, to look honestly at present limitations – all these are necessary stages in coming to terms with present reality. The way in to real peace will always be through engagement with one’s actual circumstances; the surest way for grief over what might have been to lose its hold, is for realistic hopes for a real future to begin to build.

Hopes for the future

Have you ever made a vision board? These are helpful envisioning tools that enable us to sharpen our focus on how we would like our life to be. It’s possible to make a vision board electronically, using text boxes and cutting and pasting internet images; or you can use good old-fashioned marker pens and paper, scissors, and glue, cutting out magazine pictures and sticking them on to a fair-sized rectangle of cardboard.

The vision board includes images of the way of life you choose and desire, along with affirmations and descriptions of what you would like to achieve and see manifested in your life.

If I were considering exchanging living in my own home for residential care, on my vision board I would have, right there in the middle, a picture of a view of trees through a big, low window. If I had such a view, I would be well on the way to realizing what I need to be happy. I would also include a picture of a large plateful of healthy salad – I don’t know how I would cope on a diet of white-bread sandwiches, tiny helpings of vegetables, and abundant biscuits, cake, and scones! I’d have pictures of a cat and a dog – I’d love to live somewhere where they had a resident cat and visiting pat-dogs. I would add a picture of someone in a room on her own: privacy is profoundly important to me. I might add simple affirmations such as “peace and kindness”, “quietness”, “respect”, “people who understand me”, and “no streetlights shining in through my window”.

When my vision board was all finished, I would take it with me when I went to visit prospective accommodation. Often I become intimidated, inhibited, and tongue-tied in interview situations, obsessed with being pleasant and polite, and what is important to me vanishes from my mind completely. With my vision board, I would be able to start making an assessment of whether I could be happy in this place.

A vision board essentially aims high. It is a concept arising from philosophies of positive thinking which embrace the conviction that we “dream” our world – we manifest our life experience by our thoughts; what we pay attention to, we get more of. This is observably true, and it takes very little reflection to see that sharpening the focus of our hopes, dreams, and priorities, by such means as making a vision board, significantly increases the likelihood of realizing them.

Although even pessimists would surely concede this, many remain sceptical of the extent that we can really influence what happens to us by the application of conviction and focused, sustained envisioning.

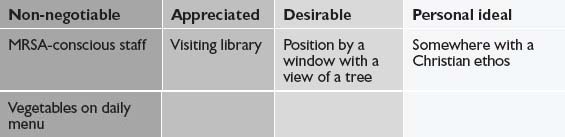

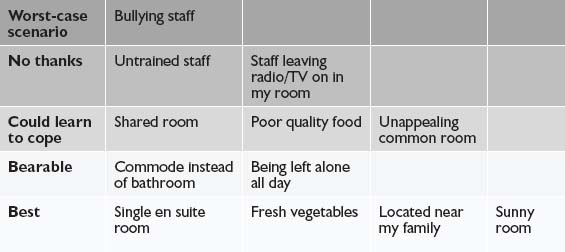

It may also be helpful, therefore, to make a list of our hopes and dreams, and another one of our fears and dreads, creating two spreadsheets: one shading from “basic non-negotiable requirements” to “personal ideal”; the other shading from “worst-case scenario” through “acceptable, I suppose” to “what I would like best if I can choose”.

It’s hard to project forward very far with some of the things that might be included on our lists. For me, at the present time, one of my “basic non-negotiable requirements” would be to enjoy complete privacy for bowel movements. I should absolutely require a single room with an en suite bathroom. But that’s now. It may be that a time will come when I cannot go to the bathroom without the help of a hoist or a wheelchair, or that I may enter residential care having had a colostomy bag fitted: in which case the parameters all change, and, as I learn to adapt to the new me, my priorities would correspondingly alter also.

On the other hand, there are some things I know will never change. Whatever happens to me, to feel the sunshine and the breeze, to hear the birds sing, and watch the seasons change will remain necessary food for my soul. Even if I lose my sight, to sit where I can smell the garden, feel the morning rise, and hear the first tentative notes of a blackbird in the dawn would mean the world to me. Even if I lose my hearing, to be where I can see the colours of the new day and the sunset would feed my soul. I ask myself: can I really insist on this? In a world where destitute people bear hideous cancers in the gutter, can I ask for a room with a view? So I have to decide: where on the spectrum do I place this, in real terms? Is it a “personal ideal”, something I long for, but cannot insist upon? Or is it a “non-negotiable basic requirement”, more important to me than cleanliness or kindness, than high-quality nutrition, adequate medication, privacy, or financial considerations?

Some people may prioritize a preference for eating in privacy. In a nursing home, it may be normal for residents to take their meals in their own rooms, but in a residential care home they may be encouraged to join the others in the dining room. Sometimes a respite client whose spouse has just died will want to be alone in their room and have meals brought to them. In some places that will be accepted; in others the view is taken that it is therapeutic for them to come to the dining room to socialize. Some residential homes place a great emphasis on socializing – with a living area where lots of clients sit and chat – whereas others do not prioritize the community aspect of residency, and clients stay mostly in their rooms. So it is important to match the care home’s approach to socializing with that of the prospective resident. Thinking through our personal priorities beforehand will help us to clarify and focus, so that we choose wisely in finding a new place to call home. Undertaking such an exercise of envisioning and thinking through helps us to know ourselves, and to enter imaginatively the options and experience of those we care for or work with, who are making the transition from living in their own homes to residential care.

To talk these matters through with people whose situation requires them now to seek out accommodation in a care home will help them to bring into clarity, into itemized order, what is probably a confused and unexamined blend of preferences and dread, a felted mat of likes and dislikes that have never been systematically considered and prioritized.

It helps to nail this right down – get a list on paper, logged into a spreadsheet with a strong visual differentiation. Perhaps a page shaded like these examples:

or this:

or like this:

However such spreadsheets are formulated, they create a concise form of record-keeping for the planning and preparation in making the transition from living independently to residential care accommodation.

They are useful in communicating with the managers of homes on the list of possible choices, because they provide at-a-glance information. People often get flustered at interviews, especially if things do not progress in the way they had imagined and mentally rehearsed; and when we are flustered, we find it hard to make use of preparatory notes when they are formulated as several pages of jottings in a notepad. Small, easy-reference, single-page spreadsheets like these are more helpful, and copies can be made so that the manager and the prospective resident can look at them together.2

Personal standards, expectations, and priorities

Our hopes and fears will be conditioned by our past experience, our family and cultural background, and our personal standards, expectations of life, and priorities.

Because these are an intrinsic part of who we are, how we grew up, and our personal history, they often remain at the level of unexamined assumptions – and the deeper their roots in our psyche, the more true that is likely to be.

It can be very helpful, therefore, in finding our niche in a community setting, to have a wise companion – whether a chaplain, a nurse or care assistant, a volunteer, or someone from among our own friends and family – to help us reflect upon and consciously express what is important to us, what motivates us, what opinions and beliefs determine our visceral reactions.

It is a time for honesty. If Mother holds extremely racist views, and she is going into a residential home where all the residents and care assistants are white, and hers will be the only brown face, it may be better for her to face honestly that she detests white people, and find a situation where she will feel less threatened, than to try to suppress or deny an attitude which may not be politically correct but is likely to become a source of distress.

I know that one of my own expectations of life is courtesy. If the time came for me to live in a nursing home, I could be very forgiving of clumsiness and human error, and I would not be especially fussy about schedules and timetables – if eleven o’clock found me still sitting in my dressing-gown, unwashed, because the day staff had got behind, that would not trouble me in the slightest – but if I were treated with discourtesy and contempt, the sparks would fly.

I know also that treats are very important to me. I have to have something to look forward to. Even if I am adequately housed, clothed, and fed, if there is no fun, no special occasion, no highlight to the week, my mood becomes very low very quickly. My treats are such things as a magazine once a month, a piece of cake or a chocolate in the afternoon, a good film on the television – nothing expensive or ambitious, but little things that make a real difference to my sense of well-being.

It is also very important to me to be close to my family. I lead a solitary life now, so days passing when I saw no one but a care assistant with a breakfast tray… lunch tray… supper tray… would not be a source of suffering. But to know that in the course of a week different family members would be calling by for a half-hour chat would mean the world to me.

My living standards have never been especially high. I am not house-proud. Our home is not dirty, but the shine on the floor wouldn’t hurt your eyes. I vacuum the middle bits of the room tolerably often, but the spiders are safe behind the sofa. I am not meticulous about washing grapes and apples before I eat them – I do it sometimes. In our house nothing matches and most things are second-hand. So if I went into nursing care, pristine carpets, pale wood bedroom furniture matching throughout, crisp chintz curtains, and accessorized lampshades would feel distinctly alienating. I like things a little old-fashioned. I like odd-shaped attic rooms tucked in the eaves of the building and conservatories that are kind of returning to the wild.

And deeply, with a passion, I hate uniforms.

My mother, on the other hand, trained as a nurse and devoted to the decor of her homes, would find a starched blue and white uniform soothing to her soul, and elegant furnishings and five-star bathrooms essential to her personal well-being.

Our standards, priorities, and expectations are intensely personal and condition our hopes and the things of which we are afraid.

At the centre of good care provision is the personal, so the essence of a good selection process includes the ability to gain trust and establish rapport, to ask the right questions, to give people the time to reflect upon and identify what is important to them, and then formulate the results of that reflection into easily assimilated data.

Points to remember

- Although most older people dread the loss of their independence and fear making a transition into residential care, this step can bring a new lease of life and a dramatic improvement in relationships with close family members who have been acting as carers.

- Researching information about suitable residential accommodation may usefully include contacting informal local networks such as Freecycle or faith groups, in addition to the usual avenues of enquiry such as published inspection reports and organizations with a specific brief of supporting and advising older people.

- Leaving one’s home for the last time is a profound and comprehensive bereavement; grief at what is lost and a space to remember and to shed tears are appropriate and helpful in making this great transition. This looking back may also include the expression of regret for what might have been and will now never be.

- Part of a constructive transition will include envisaging and developing hopes and plans for the future. Such simple envisioning tools as vision boards, charts, and spreadsheets can assist in the helpful formulation and easy communication of these hopes and plans.

- In choosing an appropriate residential setting, it is important to come to a realistic assessment of the prospective resident’s standards, priorities, and expectations, as well as their clinical status and nursing requirements.