Technology is changing so fast today that it seems we can’t keep up with it. Over the course of not too many years, we went from expensive, bad-in-low-light, low-resolution digital cameras to today’s inexpensive, versatile cameras that work well in low light and have good resolution. Today’s cell-phone cameras have better sensors than many digital cameras did just ten years ago. Similarly, processes like high dynamic range (HDR) imaging that used to require complex shooting and postproduction techniques can now be done automatically with digital cameras—and done very well. These kinds of advances aren’t being seen just in camera technology, of course. We see them occurring in every aspect of photography.

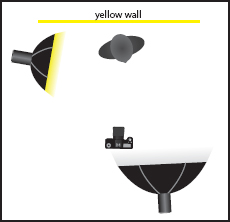

The clean, simple lighting in this image was created using one large softbox and a gelled yellow light. Shooting against a yellow wall made the image very eye-catching.

![]() second, f/8, ISO 100, 24–70mm lens at 43mm.

second, f/8, ISO 100, 24–70mm lens at 43mm.

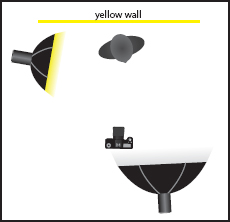

The setup here was basically the same as for the previous image, but with a grid light added.

![]() second, f/10, ISO 125, 24–70mm lens at 28mm.

second, f/10, ISO 125, 24–70mm lens at 28mm.

Today’s cell-phone cameras have better sensors than many digital cameras did just ten years ago.

Happily, a lot of these improvements also make it easier on our pockets to create the images we envision. Even lower-end cameras (especially over the last five years) have increased rapidly in terms of their quality. Today’s digital cameras have video functions and work well in low light, which is a great advantage for photographers looking to save money.

“No photographer is as good as the simplest camera.”

—Edward Steichen

In the past, when higher ISO settings yielded unacceptable noise levels in your images, working in low light meant using a fast lens (one with a very wide maximum aperture). That could be a costly proposition. Below is an example of what I’m talking about; notice how rapidly the price jumps with each fractional increase in the maximum aperture.

Canon 50mm Lens

f/1.8—$100

f/1.4—$350

f/1.2—$1500

Keep in mind that each of these price increases buys you only about ½ stop more light! Today, with the improved sensor technology in our digital cameras, you can often increase the ISO sufficiently (without incurring too much noise) and stick with a cheaper lens. And if you can get the results you want without spending thousands of dollars on lenses, why wouldn’t you?

This is a great advantage for photographers looking to save money . . .

In the past, camera phones took poor, blurry images—but Apple changed the game with the iPhone’s great little camera, which has good focus, useful exposure controls, and even a small flash. Amazing.

Portability. Let’s start with the advantages of using a camera phone. The major advantage is portability and ease of use. If you are out someplace with a camera phone, you can capture images without much hassle. For example, shooting nudes in public can be very risky. If you get caught with a big, professional-looking digital camera, you can get in trouble. However, if you get caught taking nude photos of a friend or loved one with your little camera phone, you are more likely to be let go with a warning.

Each of these images was shot with a cell-phone camera.

Apps and GPS. Another plus is the ability to use apps, which will let you do everything from smoothing the skin to adding crazy effects. Most modern cell phones also tag your images with GPS data. This can be bad if you are shooting someplace you shouldn’t be—but if you’re an active shooter, GPS data can be very helpful for remembering where an image was created. Also, if you are traveling or looking for new locations to shoot around your town, you can hop on a site like Flickr and explore locations by viewing GPS-tagged images. To do this, go to www.flickr.com/map, then browse to the location you want to explore and click “search this map.”

In the future . . . who knows? Camera phones might easily surpass point-and-shoot cameras.

Drawbacks. There are a few drawbacks, however, that you should keep in mind when using a camera phone. First, if you shoot video, they currently have bad rolling-shutter issues. More importantly, there is a stigma around shooting with a camera phone. Good or bad, it is what it is. A few shots with a camera phone are okay, but doing a whole photo shoot with a camera phone is a bit laughable—and not really professional at the current time. But in the future . . . who knows? Camera phones might easily surpass point-and-shoot cameras.

An additional problem is that most camera phones can’t shoot RAW images—and I love RAW images (we’ll talk about this file format later in the chapter). Finally, there are not many accessories for camera phones. For example, even if you can find different lenses or external flashes for your camera phones, they are not standardized. The devices may well work on one version of the phone but not the next.

I have read my fair share of photography books and web sites, but I never see too much about point-and-shoot cameras being used to photograph models. However, I have worked with many photographers who love their point-and-shoot cameras and use them all the time—sometimes for the production of fine-art images.

The fact that point-and-shoot cameras account for over 40 percent of the total sales in the photography market shouldn’t come as a big surprise; there are some really great advantages to shooting with them. Point-and-shoot cameras are light, portable, equipped to shoot video, and have a good battery life. All of these things are very important for shooting. There are even point-and-shoot cameras that are waterproof. Underwater nude images are surreal and very artistic, but using a digital SLR camera to create them can be expensive.

There are many point-and-shoot cameras on the market, so you won’t have trouble finding one that works perfectly for you. The important things to ask yourself are:

How fast or how slow is the camera? (Does it focus quickly? What is the burst rate?)

Can I control the exposure settings manually?

Does it shoot video?

Does this camera fit my needs?

The small size of point-and-shoot cameras makes it easier to shoot quickly—and without attracting attention—in public places.

Speed. In the past, point-and-shoot cameras were really slow; you would push the shutter button and nothing would happen for a few seconds and then you would get a picture. When taking pictures of models, those few seconds can be the difference between a great shot and a bad shot. Luckily, most of the current camera manufacturers have worked on this and now they are fast as lighting. However, if your point-and-shoot is a few years old, you might want to think about buying a new one.

Manual Settings. Manual settings are another thing you’ll probably want. Why does this matter? In many cases, it won’t; there are a lot of scenes/subjects for which the automatic mode will work just fine. However, there are times when you’ll want to override the automatic settings—say, for a very low-light scene or a very bright one where the automatic metering can struggle. Having the ability to change the settings is a nice option.

Your Individual Needs. The final question I listed was this: Does this camera fit my needs? It sounds silly, but it’s important. For example, earlier I talked about waterproof cameras. I don’t photograph models underwater and I live in Las Vegas, where it rains only once or twice a year. So, for me, investing in a waterproof camera wouldn’t be very useful. If I were looking for a new point-and-shoot, I would want to make sure the images looked good, that it shot quickly, that the LCD or viewfinder was really bright, and that it had wireless connectivity and GPS built in to it. Those are the features that are important to me—but everyone will have different ideas of what is important to them.

Mirrorless Cameras and Rangefinders

Over the last few years, there has been a huge leap forward in advanced point-and-shoot cameras, sometimes called rangefinders or mirrorless cameras. A rangefinder has a small optical viewfinder that doesn’t use a mirror to reflect the image. Mirrorless cameras don’t have an optical viewfinder, but sometimes a small LCD screen (instead of the optical viewfinder) plus a larger LCD screen on the back of the camera. These cameras offer a great blend of traditional digital camera features but in a smaller package. They have interchangeable lenses, manual control, the ability to shoot videos, and they let you create RAW files—most of the important features that a DLSR has (see next section), but in a small, lightweight body. This class of camera is something to keep an eye on, because if you need more than a point-and-shoot but don’t want a full-size digital camera, this option could be perfect.

Photographing a model with a point-and-shoot camera. This Canon model has a built-in zoom lens and flash, plus it can shoot video. It is light-weight—and even the extra batteries aren’t heavy to carry around.

These images were shot using a Samsung point-and-shoot camera.

These cameras offer a great blend of traditional digital camera features but in a smaller package.

Most of the images in this book were shot with a digital single-lens reflex (or DSLR) camera, because it gives me the most flexibility when I shoot. Today’s digital cameras are much better than those from just a few years ago—and they’re getting cheaper and cheaper. Mid-level cameras like the Canon 7D (currently priced around $1000) are even being used by Hollywood in the creation of multimillion-dollar movies like The Avengers, Black Swan, Act of Valor, and Red State.

These images were shot using a Canon DSLR.

Think about that. Hollywood often spends hundreds of thousands of dollars on cameras and lenses to create movies, yet they are now using the same camera that thousands of regular-guy photographers are using. Isn’t that great? For $1000, you can have the same tool that feature filmmakers are using. The real question is why is Hollywood using this camera? Simple. It produces fantastic video and great images—basically, it works!

One advantage of shooting with a DSLR is that it increases your lighting options.

With a DLSR, the camera body, external flash, batteries, and lenses add up to around 20 pounds of gear in my camera bag.

Some of the best things about using DSLRs are that they open up additional lighting options, allow you to use interchangeable lenses, and give you the ability to shoot RAW images. Let’s talk about each of these items a bit.

Lighting. With a DSLR, you can begin to add light to your images in more powerful ways. This could involve the use of small flash units (like Canon Speedlites) or large studio-strobe kits. If you know how to add and control light effectively, this can give you a great deal of freedom. However, many photographers run out and buy expensive strobes, thinking all of their lighting problems will be solved. That’s not the case. We’ll look at flash and strobe lighting in the next chapter.

Interchangeable Lenses. Switching lenses can change the mood of a shoot—from risky, to boudoir, to artistic. You can capture a whole-body shot, then switch the lens and capture a very intimate fine detail. Having a few different lenses to choose from is nice. My workhorse lens is a 24–70mm zoom, which I push to the limit; I know what it will and will not do. I now have several other lenses in regular use, but for years this was one of only two lenses I owned. I believe in knowing your tools as well as possible; it will help you grow as a photographer.

RAW Files. Being able to shoot RAW files (files that are not processed by the camera’s built-in software) is very important. With these files, you are getting the most pure information possible and you have the most potential for finishing the image exactly as you want it. Think of it this way: if you go to a fast-food place, you get the burger the way they make for you. You can maybe change it a little, but you really can’t customize it that much. If you want it medium rare, or with green onions and avocados, you’re out of luck. Imagine, instead, you went to the supermarket and got the raw materials for your sandwich (hamburger, buns, avocados, mayonnaise, etc.). This would let you make that burger any way you wanted. This is akin to shooting RAW images—and, just as with shooting RAW images, the trade-off is that you will have to invest a bit of time in your final product. That’s what it takes to get exactly what you want.

Two of these images were shot with a high-end Canon DSLR ($5000). Two of them were shot with a mid-range Canon point-and-shoot ($500). Can you tell which images were shot with which camera? (Answers appear on the next page.) The DSLR is a very heavy camera that needs an external flash. When we’re walking several miles into a shooting area, carrying all that equipment can be an issue. The point-and-shoot, on the other hand, has a built-in flash and fits in your pocket. These are some things to think about when selecting a camera.

ANSWERS TO QUESTION ON PREVIOUS PAGE—The photos on the left (top and bottom) were created with a point-and-shoot camera. The photos on the right (top and bottom) were created with a DSLR.

The trade-off is that you will have to invest a bit of time in your final product . . .

The top image was created using a DLSR that sells for almost $5000. The bottom image was created using a point-and-shoot camera that retailed for under $500. As you can see, the price of your camera isn’t a determining factor in the success of your images.