Students of literature are routinely told that Thackeray is an ‘omniscient’ novelist; indeed, that with Fielding he is probably the perfect specimen of the type. He himself tells us, repeatedly and with apparent complacency in Vanity Fair, that ‘the novelist knows everything’. But this omniscience has its holes. The reader is teased by what this allegedly all-knowing narrator would seem not to know, will not acquaint himself with, or declines to impart. Omniscient he may be; omnidictive he is not.

Most provoking of the text’s silences is that concerning Jos’s death. He dies in mysterious circumstances on the continent, sometime in the early 1830s, while in the dangerous company of Becky Crawley. From his first encounter with her, some twenty years before, Jos has been in danger from this fatal woman. In 1813 she almost netted him; but George Osborne, unwilling to have a governess marry into the family (‘low enough already, without her’, Chapter 6) frightened the fat man off. At Pumpernickel, despite Dobbin’s efforts, she finally lands her prey. Becky cannot marry Jos (Rawdon, her estranged husband, is still staving off the fevers of Coventry Island). But she lives with her victim until he dies – prematurely. She is his insurance beneficiary; the rest of the nabob’s once substantial wealth has mysteriously evaporated. And in later life Becky is a very prosperous lady, we are told. When she was first setting her hat at Jos in Russell Square she was netting a purse; now, at last, it would seem that the purse is comfortably full.

How does Jos die? The insurance people are suspicious. Their solicitor swears it is ‘the blackest case that ever had come before him’ (Ch. 67). Thackerayan innuendo confirms our sense that Becky helped Jos out of the world. Her solicitors are ominously named Messrs. Burke, Thurtell and Hayes. Burke, with Hare, was the Edinburgh body-snatcher who killed and sold corpses to the university school of medicine. John Thurtell was a murderer, hanged in 1824. Catherine Hayes was a husband killer, celebrated by Thackeray in his anti-Newgate satire, Catherine (1839).

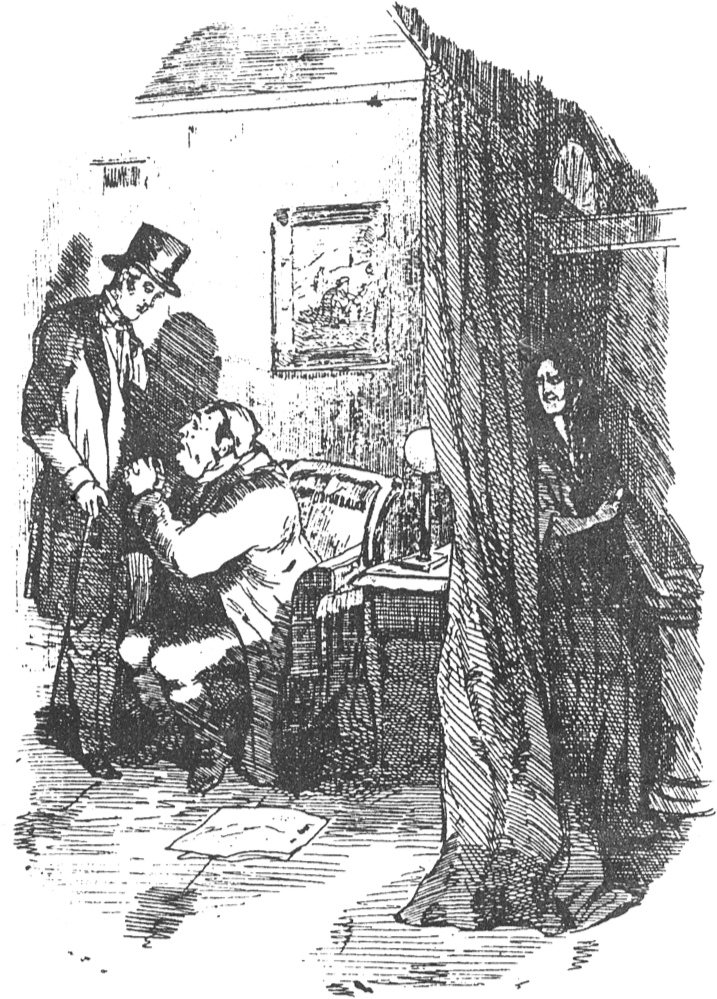

There is another broad hint in the penultimate full-plate illustration to the novel, ‘Becky’s second appearance in the character of Clytemnestra’.

Becky’s first appearance as the Greek husband-killer was in the charade at Gaunt House, just before she betrayed Rawdon into the hands of the bailiffs. Here we feel that she will use the knife that, somewhat melodramatically, Thackeray shows her holding. (An ironic Hogarthian print of the good Samaritan is behind Jos, who vainly implores an implacable Dobbin to help him.)

It all points one way. But why does Thackeray not tell us straight out? It is a mote that he seems deliberately to have left to trouble generations of readers. And when asked in later life by just one such troubled reader; ‘did Becky kill Jos?’ the novelist is reported to have merely smiled and answered, ‘I don’t know’.

Becky’s second appearance in the character of Clytemnestra

‘Was she guilty?’ The narrative asks that question of Becky (but gives no direct answer) at two crucial junctures; first, in the liaison with Steyne; secondly, after Jos’s death. It is, of course, odds on that Becky was thoroughly guilty of both these and many other like offences. Would the notoriously lecherous Marquess of Steyne have given Becky a cheque for over a thousand pounds, provided for her son and companion Briggs, and given her diamonds (which she feels obliged to hide from her husband) if he were not enjoying with her what he more flagrantly enjoys with the Countess of Belladonna? So too with Jos’s untimely decease; any open-minded reader concurs with the insurance office’s suspicion.

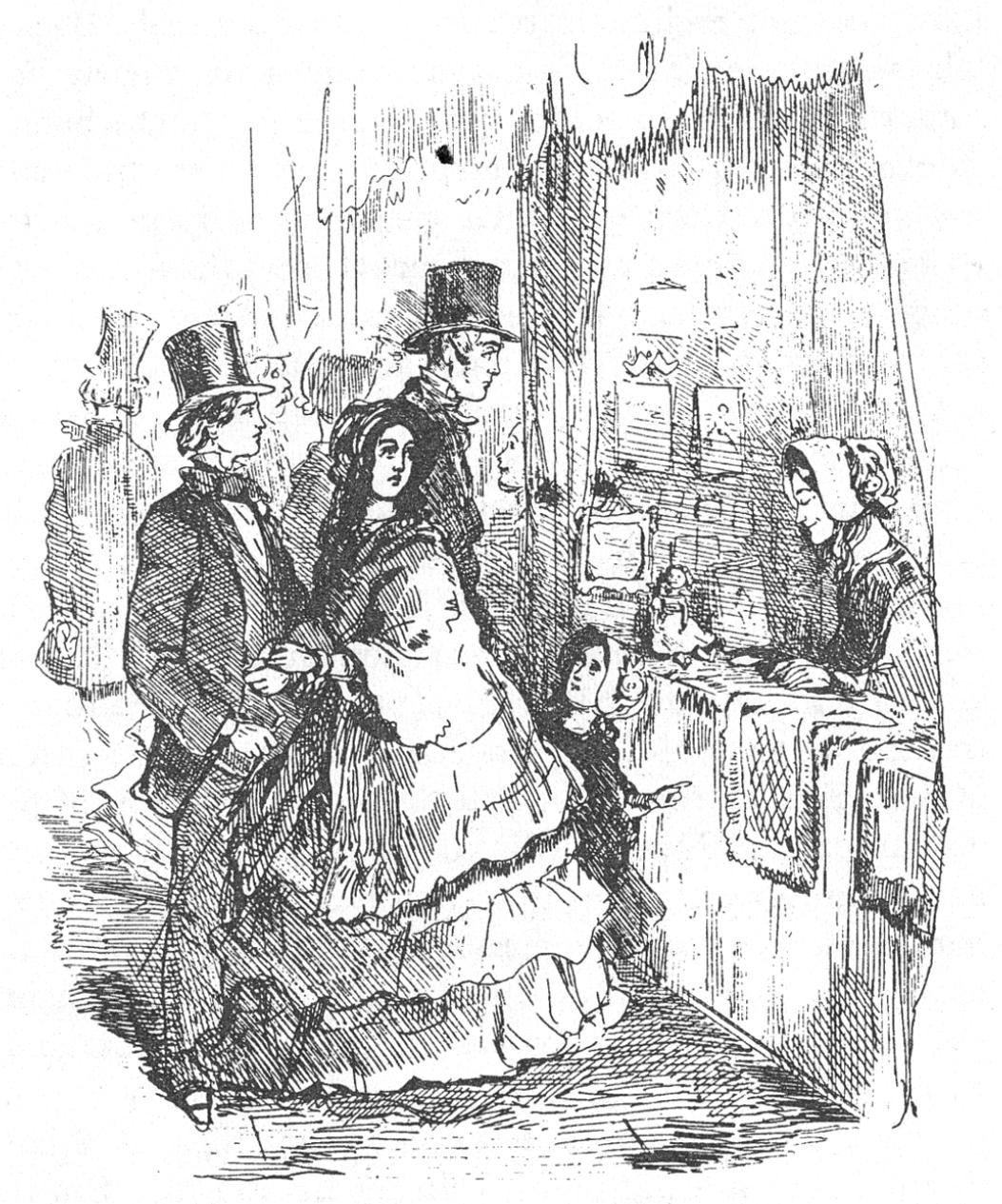

If we accept the hint that Becky indeed killed Jos, then the last illustration ‘Virtue rewarded: a booth in Vanity Fair’ (with its ironic echo of Fielding’s Amelia, or Virtue Rewarded) is one of the most un-Victorian endings in Victorian fiction. I can only think of one other Victorian novel in which a main character escapes punishment for murder (Mrs Archer Clive’s eccentric romance, Paul Ferroll, 1855). To have left Becky unpunished for her capital offence would also have been radically out of character for Thackeray, who had been one of the main castigators of the so-called Newgate Novel – more particularly the ‘arsenical’ variety recently made notorious by Bulwer-Lytton’s Lucretia (1846), a novel which The Times called ‘a disgrace to the writer, a shame to us all’ – on the grounds that it glorified wives who poisoned husbands for gain. Thackeray had built his early career around attacks on the immoralities of Bulwer-Lytton’s fiction and its depictions of vice rewarded.

Would Thackeray, one wonders, have emulated a writer whom he loathed? More significantly, as has been pointed out by a number of commentators on Vanity Fair, murder seems entirely out of character in Becky – an adventuress who might well stoop to some well-paid adultery but is, we feel, no homicidal psychopath capable of the premeditated crime of slow poisoning by arsenic.1

To return to the text which surrounds the Clytemnestra illustration. In the last years of his life the ‘infatuated man’, Joseph Sedley, is reported to be entirely Becky’s ‘slave’. Colonel Dobbin’s lawyers (who have clearly been undertaking some discreet spying on their client’s behalf) inform him that Jos has taken out a heavy insurance upon his life. Moreover; ‘his infirmities were daily increasing’ (Ch. 67). What, one may well ask, are these ‘infirmities’ – the physical decrepitude consequent on a lifetime’s gluttony? Or the slow effects of criminally administered toxins?

Virtue rewarded. A booth in Vanity Fair

Dobbin, at his wife’s alarmed request, goes to visit his brother-in-law in Brussels, where he is staying in an adjoining apartment to Mrs Crawley. She is living in great style, presumably on Jos’s dwindling store of money. A mysteriously terrified Jos tells Dobbin that Mrs Crawley has ‘tended him through a series of unheard-of illnesses, with a fidelity most admirable. She had been a daughter to him’ (Ch. 67). He, despite these daughterly attentions, is perceived by the Colonel to be in ‘a condition of pitiable infirmity’. Mrs Crawley, Jos further insists to a disbelieving Colonel, ‘is as innocent as a child’. The Colonel leaves, sternly indicating that he and Mrs Dobbin can never visit such as Mrs Crawley and her consort again. Before doing so, he urges Jos ‘to break off a connexion which might have the most fatal consequences to him’ (Ch. 67). Three months later Jos duly dies at Aix-la-Chapelle, a watering place, whither he and Mrs Crawley have repaired in a vain attempt to recover his health. There follows the coded business about the lawyers, Burke, Thurtell and Hayes, and the insurance company’s dark suspicions.

If Becky killed Jos, how was it done? By poison? Or is he, as it seems in his last interview with Dobbin, terminally ill and terrified of dying alone? Someone, that is, who is going to depart the world without the assistance of arsenic. The Clytemnestra picture is, on close inspection, baffling. It is made clear in the text that Becky is not, in fact, hiding behind the screen. (Jos is morbidly careful to arrange the meeting ‘when Mrs Crawley would be at a soirée, and when they could meet alone’, Ch. 67.) Nor, if Becky actually does kill Jos, is the deed done with a knife. Whatever else, Becky is no Lizzie Borden.

What the picture would seem to allegorize are the exaggerated fears and suspicions of the respectable world (‘I warrant the heartless slut was behind the screen all the time, just biding her time to kill the poor man!’). And Thackeray casts those suspicions in their most lurid form. So lurid, in fact, that the discriminating reader must dismiss them as preposterous. Of course – if we weigh up all the prior evidence Becky is no cutthroat. There is no question but that she is an unscrupulous woman, taking monetary advantage of a dying man, treating him doubtless with the same careless kindness which characterizes her last acts towards Amelia (whose path to a happy marriage she clears, with some well-placed malicious information about George Osborne).

In short, in this last section of the novel Thackeray is playing a game with his readers. He lures them – by flattering their responsiveness to authorial nods and winks – into thinking themselves cleverer than they in fact are. Complacently we readers, priding ourselves on being sophisticated enough to decode the Burke, Thurtell, Hayes, and Clytemnestra allusions, fall into the same vulgar prejudice as does the ‘world’ that condemns Becky. Does Becky kill Jos? Of course she doesn’t – but maliciously wagging respectable tongues will never believe otherwise.

Notes

1. Keith Hollingsworth in The Newgate Novel (Detroit, 1963), 212–15, argues that Vanity Fair is, in its last pages, emulating the Newgate Novel. Hollingsworth accepts that ‘Rebecca murders Joseph Sedley’ and that she does it by poison, presumably arsenic, the poison of choice for murderesses in the 1840s (p. 212).