It helps to picture the dramatis personae of Middlemarch less as a community of English townspeople of the early nineteenth century than as a Papuan tribe – each connected to the other by complex ties of blood and marriage. Unknotting these ties requires the skills of the anthropologist rather than those of the literary critic. Let us start with Casaubon. Early in the narrative, the middle-aged vicar of Lowick is most vexed when Mr Brooke (making unwarranted deductions from their age difference) refers to young Will Ladislaw as ‘your nephew’. Will, as Casaubon testily points out, is his ‘second cousin’, not his nephew. We learn from questions which Dorothea asks on her first visit to Lowick, that Casaubon’s mother, whose Christian and maiden names we never know, had an elder sister, Julia. This aunt Julia – as we much later learn – ran away to marry a Polish patriot called Ladislaw and was disinherited by her family. Julia and her husband had one child, as best we can make out. Ladislaw Jr. (we never learn his first name) inherited from his father a musical gift which the son turned to use in the theatre – to little profit, apparently. In this capacity he met an actress, Sarah Dunkirk. Sarah, like Casaubon’s aunt Julia, had run away from her family’s household to go on the stage. At some point before or after running away, she discovered that her father, Archie Dunkirk, who at one point in the text is alleged to be Jewish (although a practising nonconformist Christian of the severest kind), was engaged in criminal activities. He is reported to have had a respectable pawnbroking business in Highbury, and another establishment which fenced stolen goods in the West End. Sarah broke off all relations with her mother and father on making this discovery. They have another child, a boy, and effectively disowned their disobedient daughter.

Sarah was subsequently married to, or set up house with, Ladislaw Jr. The couple had one child (Will) before the father prematurely succumbed to an unidentified wasting disease. Before dying, he introduced himself to Edward Casaubon, who generously undertook to take care of the penniless widow and child. Will is too young to remember anything distinctly about his father. On her part Mrs Ladislaw died in 1825, some ten years after her husband, of what is vaguely described as a ‘fall’.

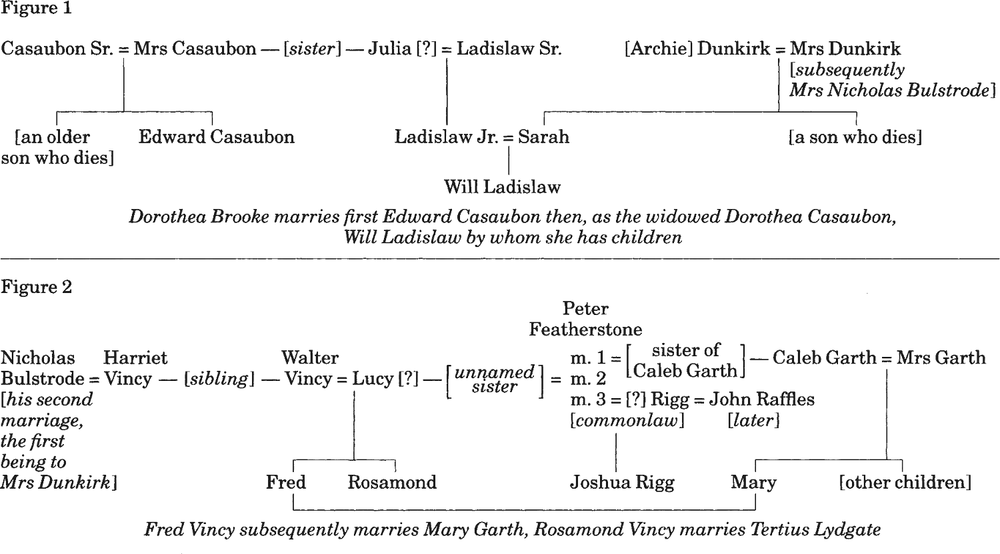

At some point after Sarah Dunkirk’s breaking off all relations with her parents, her brother died. Shortly after this her father also died. In the distress of her double bereavement, Mrs Dunkirk (now an old lady, and – although she does not know it – a grandmother) turned to a young evangelical clerk of her husband’s, called Nicholas Bulstrode. Eventually, she married the young man. The disparity in age precluded children. As she approached death, a distraught Mrs Bulstrode made desperate attempts to locate her daughter Sarah with the hope of reconciliation. But, although he had discovered their whereabouts, Bulstrode – assisted in his act of deception by another former employee of Dunkirk’s, John Raffles – suppressed all information about Sarah and her little boy. Raffles in fact makes contact with Sarah twice, although he only informs Bulstrode about the first encounter (this is important since, for complicated reasons, he only discovers Ladislaw’s name on the second occasion). When Mrs Bulstrode died, Bulstrode, by his act of deception, inherited his wife’s entire fortune and used it to set up a bank in Middlemarch. It will help at this point to refer to a family tree (see Fig. 1). As Farebrother puts it with uncharacteristic coarseness later in the narrative (presumably echoing Middlemarch gossip): ‘our mercurial Ladislaw has a queer genealogy! A high spirited young lady and a musical Polish patriot made a likely enough stock for him to spring from, but I should never have suspected a grafting of the Jew pawnbroker’ (Ch. 71).1

This means, of course, that Bulstrode is Casaubon’s distant cousin by marriage – although both are oblivious of the relationship. In Middlemarch, the still-young, newly widowed, and now rich Nicholas Bulstrode married Harriet Vincy. She is a sister of Walter Vincy, manufacturer, husband to Lucy Vincy and father of the novel’s jeunes premières Fred and Rosamond. Mrs Vincy’s sister was the second wife of the rich skinflint, Peter Featherstone. Featherstone’s first wife was a sister of Caleb Garth, father of Mary Garth and other children who feature on the edge of the novel’s plot. Peter Featherstone has no child by either of these two wives, both of whom predecease him by some years. But, unknown to his hopeful heirs (among whom the most hopeful is his nephew Fred Vincy), Peter Featherstone had a third, common-law wife, called Rigg. By this Miss Rigg, Featherstone has an illegitimate son, Joshua, born in 1798. Discarded by Featherstone, Miss Rigg subsequently married John Raffles, the aforementioned employee of Dunkirk and conspirator with Bulstrode to defraud Will Ladislaw of his inheritance. It will help here to refer to another tree (see Fig. 2).

Thus John Raffles, fence, blackmailer, gambler, the most despicable character in the novel, is related to Casaubon and (by subsequent marriages in the novel) to Lydgate, Dorothea Brooke, Will Ladislaw, and Sir James Chettam. The line of connection goes as follows: Raffles’s wife is the mother of Peter Featherstone’s child and heir; Peter Featherstone is the husband of Lucy Vincy’s sister; Lucy Vincy is the wife of Walter Vincy, the mother of Rosamond (who marries Lydgate) and the sister of Harriet Bulstrode; Harriet is the husband of Nicholas Bulstrode; Bulstrode was the second husband of the former Mrs Dunkirk; Sarah Dunkirk was the wife of Ladislaw Jr.; Ladislaw Jr. was the cousin (by his aunt Julia) of Edward Casaubon; Casaubon is the husband of Dorothea; Dorothea is the sister-in-law of Sir James Chetham. Put simply, Bulstrode is (by marriage) Casaubon’s cousin, Dorothea’s cousin, Will’s step-grandfather, and related in some way to virtually everyone in the novel.

Every main character in Middlemarch’s massive plot can be connected by lines of consanguinity or marriage in this way – with the exception of Farebrother (who none the less regards himself as an ‘uncle’ to the Garth children). Clearly, it is part of Eliot’s grand design, and pertains to what Rosemary Ashton aptly calls, ‘the central metaphor of Middlemarch, the web’.2 One of the odd features about the novel, however, is that we are not always sure how aware the main characters are of the webs of kinship that exist between them. This is particularly the case with Casaubon.

We know something of Casaubon’s background from incidental remarks. Before their marriage, he tells his fiancée Dorothea that his mother was one of two daughters, just like Dorothea and Celia. Of his father we know nothing, except that Lowick is the family home and Casaubon’s mother was a young woman there – whether she had been brought there as a bride, or had lived there as a child, we do not know. Edward was a younger son, and – after ordination – was given the living at Lowick. Subsequently his elder brother died (both parents were evidently already dead at this point) and he came into the manor as well as the vicarage. All these Casaubon deaths must have occurred much earlier, in the narrative’s distant prehistory. It was evidently as the head of the family that Ladislaw Jr. approached Edward for help, and this was when Will was still too young to know anything about his circumstances other than that he was very hungry.

In this context one may note a remark which the Revd Cadwallader makes early in the narrative to Sir James Chettam. Sir James, still smarting at the absurd idea that Dorothea, whom he loves, should choose to marry such a dry stick as Casaubon, asks what kind of man he is. ‘He is very good to his poor relations’, Cadwallader says, using the plural form of the word:

he … pensions several of the women, and is educating a young fellow [i.e. Will] at a good deal of expense. Casaubon acts up to his sense of justice. His mother’s sister made a bad match – a Pole, I think – lost herself – at any rate was disowned by her family. If it had not been for that, Casaubon would not have had so much money by half. I believe he went himself to find out his cousins, and see what he could do for them. (Ch. 8; my italics)

We never discover who these unnamed ‘relations’, ‘women’, ‘cousins’ are. They make no appearance at Casaubon’s funeral, nor is any bequest to them mentioned in the subsequent lengthy discussion of the will. Dorothea inherits everything, as we understand (Will, who might have expected ‘half’, is spitefully excluded). What is interesting, however, is Cadwallader’s recollection that Casaubon has made active investigations about his relatives, presumably on coming into his inheritance. He would surely have extended his inquiries to his aunt Julia and her offspring and might even have found out something about the murky world of the Dunkirks.

In conversation with Dorothea shortly after Casaubon’s first heart-attack, Will casually tells her that his ‘grandmother [was] disinherited because she made what they called a mésalliance, though there was nothing to be said against her husband, except that he was a Polish refugee who gave lessons for his bread.’ Dorothea goes on to ask what he knew about his parents and grandparents, and Will replies:

only that my grandfather was a patriot – a bright fellow – could speak many languages – musical – got his bread by teaching all sorts of things. They [i.e. grandfather and grandmother] both died rather early. And I never knew much of my father, beyond what my mother told me; but he inherited the musical talents. I remember his slow walk and his long thin hands; and one day remains with me when he was lying ill, and I was very hungry, and had only a little bit of bread. (Ch. 37)

Shortly after, Will recalls, ‘my father … made himself known to Mr Casaubon and that was my last hungry day’. And shortly after that, his father died.

An initial mystery is why Julia’s alliance with a cultivated Pole should have resulted in such a total alienation from her family. A second mystery is Casaubon’s extraordinary disinclination to discuss anything to do with Will’s origins. He returns all Dorothea’s inquiries with ‘cold vagueness’ and refuses outright to answer any of his wife’s questions about ‘the mysterious “Aunt Julia”’ (Ch. 37). Thirdly, one may wonder why Casaubon, an extraordinarily rectitudinous man, does not make over part of the family portion to Will, if he is the legitimate grandson of the older daughter (Julia) who would – had she not made her mésalliance – have inherited half or more of her parents’ wealth, wealth which has all funnelled into the sole possession of Casaubon.

These questions, particularly the last, should be borne in mind when scrutinizing Raffles’s account of how, all those years ago, he discovered Will and his mother and kept the news secret from Mrs Dunkirk, at Bulstrode’s behest. ‘Lord, you made a pretty thing out of me,’ Raffles tells Bulstrode, on their reunion at Stone Court: ‘and I got but little. I’ve often thought since, I might have done better by telling the old woman that I’d found her daughter and her grandchild: it would have suited my feelings better’ (Ch. 53). He goes on, after revealing that Bulstrode gave him enough to emigrate comfortably to America,

I did have another look after Sarah again, though I didn’t tell you; I’d a tender conscience about that pretty young woman. I didn’t find her, but I found out her husband’s name, and I made a note of it. But hang it, I lost my pocket book. However, if I heard it, I should know it again … It began with L; it was almost all l’s, I fancy.

The name, of course, is Ladislaw. This accounts why it is Bulstrode does not put two and two together when his young step-grandson turns up in Middlemarch. But under what name, then, did Raffles first discover the mother and child? One has to assume he discovered them as ‘Sarah and Will Dunkirk’. It beggars credulity that if he were charged to find proof of their identity, with £100,000 at stake, he would not have made some attempt to ascertain names and identities. Without some name to work with, how could he (or his lawyers) have found them in the first place?

This may be taken in conjunction with Ladislaw’s extreme sensitivity on the subject of his mother. Consider, for example, Raffles’s overture to Will, once he has tumbled to who he is. ‘Excuse me, Mr Ladislaw’, he asks:

‘was your mother’s name Sarah Dunkirk?’

Will, starting to his feet, moved backward a step, frowning, and saying with some fierceness, ‘Yes, sir, it was. And what is that to you?’ … ‘No offence, my good sir, no offence! I only remember your mother – knew her when she was a girl. But it is your father that you feature, sir. I had the pleasure of seeing your father too. Parents alive, Mr Ladislaw?’

‘No!’ thundered Will, in the same attitude as before. (Ch. 60)

One notes that Raffles does not say – as would be normal – ‘was your mother’s maiden name Sarah Dunkirk?’ One notes too the extraordinary anger which Raffles’s inquiry provokes. The same angry response is evident in Will’s interview with the repentant Bulstrode, very shortly after:

‘I am told that your mother’s name was Sarah Dunkirk, and that she ran away from her friends to go on the stage. Also, that your father was at one time much emaciated by illness. May I ask if you can confirm these statements?’

‘Yes, they are all true,’ said Will … ‘Do you know any particulars of your mother’s family?’ [Bulstrode] continued.

‘No; she never liked to speak of them. She was a very generous, honorable woman,’ said Will, almost angrily.

‘I do not wish to allege anything against her …’ (Ch. 61)

One notes again the use of the name ‘Sarah Dunkirk’ rather than, ‘your mother’s name was Sarah Dunkirk before marriage’. Also prominent is Ladislaw’s touchiness at any aspersion against his mother’s ‘honour’.

There seems at least a prima-facie case for wondering whether or not Will was born out of wedlock. This would explain why it is he and his mother are first found by Raffles under some other name than Ladislaw (presumably ‘Sarah Dunkirk and son’). Irregular unions were common enough in the nineteenth-century theatre world. It is worth recalling too that Will Ladislaw is known to be an idealized portrait of George Eliot’s consort, G.H. Lewes. And, as Rosemary Ashton’s recent biography has revealed, Lewes was illegitimate.3 As Ashton notes, Lewes may not himself have known the fact. She adds: ‘It is not surprising … that we know nothing about G.H. Lewes’s earliest years. They must have been precarious socially, and probably financially as well … Whatever Lewes was told about his own father … he nowhere mentions [him] in his surviving writings’ (p. 11). There is, of course, a difference. It seems that at some point Ladislaw Jr. did marry Sarah Dunkirk – possibly as he felt death was coming, and he needed to hand over responsibility to Casaubon, he made an honest woman of Sarah and a legitimate child out of Will. All this is highly speculative. But any ideas we form about this aspect of the novel are driven to guesswork. One could, of course, speculate that Sarah when she left her parents took on a stage-name, and it was under this that Raffles first found her. There is also the baffling detail that at one point in the narrative Raffles seems to refer to Sarah’s family name as ‘Duncan’ (see Ch. 60).

One is on firmer ground with hypotheses about what must have been going through Casaubon’s mind, and agonizing him, as he watched Dorothea and Will forming a close relationship. He may well have known (from his interviews with Ladislaw Jr. and Will’s mother, who has been alive until quite recently) about the discreditable ‘Jew pawnbroker’ business, if only vaguely. Should he tell the young man? Casaubon may also, as I have speculated, have known that Will was born out of wedlock (which would explain why he had not made part of the family fortune over to him, as a legitimate heir). At the very least, it seems strongly probable that Casaubon is possessed of some guilty knowledge and that the anxiety of it hastens his premature death.

Notes

1. It is feasible that Farebrother is simply retailing vulgar Middlemarch gossip here (as the narrative earlier suggests), assuming that all pawnbrokers are Jewish. Since Dunkirk attends the same fundamentalist Christian church as Bulstrode he would have to be an apostate as well as Jewish. If the ‘grafting of the Jew pawnbroker’ is accepted as true it may be taken to have consequences in the text. Bernard Semmel, in George Eliot and the Politics of National Inheritance (New York 1994), 97–8, suggests that Ladislaw’s revulsion at Bulstrode’s offer to make amends may reflect his horror at discovering his unsuspected Jewish ancestry. Semmel, who accepts that Dunkirk was Jewish (and Ladislaw therefore partly Jewish), further suggests that the characterization of Will may owe something to Eliot’s conception of Disraeli, who in 1830 would be about the same age as her hero.

2. Middlemarch, ed. R.D. Ashton (Harmondsworth, 1994), p. xxi.

3. R.D. Ashton, G.H. Lewes (Oxford, 1990), 10–11.