Many are familiar with the early twentieth-century Dada movement, when anti-war artists from a range of countries attacked the social and cultural order that had given rise to World War I. In the current literature, it is commonplace to date Dada’s New York beginnings to French artist Francis Picabia’s arrival in June of 1915 and his five “object portraits” published in the July-August issue of the avant-garde art journal 291.1 These depictions are rightly singled out because they embody so many of the definitive features of Dadaist production in New York, in that their evocation of industrialism and commercialism violated the conventions defining art while simultaneously setting off a chain of associative readings that transgressed the subject at hand.

Where I part with the prevailing view, however, is in regard to Picabia’s attitude towards the United States and, by extension, the role ascribed to him in the development of American modernism. Art historian Wanda Corn and others have argued that the object portraits were a celebratory incorporation of American popular culture into high art, a broadening, if you will, of the modernist landscape to include the American point of view.2 However, this reading downplays the complexity of Picabia’s portraits as well as the dissident politics that inspired them. By way of reply, this chapter focuses on one of these works, Portrait of a Young American Girl in a State of Nudity (1915), as a case study in how the advent of Dada in New York was bound up with an anarchist critique of contemporary American culture and the distinctive type of modernity it embodied.

Picabia was a Paris-based painter who had first visited the United States in the company of his wife, Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia, in 1913 to attend the opening of a large-scale exhibition of European and American modernism known as the Armory Show. The exhibition began in New York (February 17-March 15) and then traveled to Chicago (March 24-April 16) before closing in Boston (April 28-May 19). The Picabias arrived in New York on January 20 and stayed on through February and March before departing home for France on April 10. In New York, the couple met with the photographer Alfred Steiglitz, who ran a small non-commercial gallery (known as “291,” after its Fifth Avenue address) and journal—Camera Work—to show-case the latest experiments in European and American modernism. During their stay, the Picabias grew close to Steiglitz and many others in his circle, notably the Mexican caricaturist Marius de Zayas, the anarchist journalist Hutchins Hapgood, and Paul Haviland, a wealthy art collector and photographer.3

Prior to his New York visit, Picabia had been exhibiting for just under two years with a group of Parisian cubists (the “salon cubists”) led by painter and theorist Albert Gleizes, who co-authored the seminal statement, Cubism (1912), with fellow painter Jean Metzinger. Gleizes was the group’s organizational dynamo who arranged exhibitions, promoted the movement in the press, and discouraged any aesthetic deviations.4 The group’s successes in Paris ensured that when the American organizers of the Armory Show went to France in a quest for modern art, they would return with a substantial list of cubist paintings and sculpture. At the Armory Show, Picabia exhibited four paintings, including Dances at the Spring (1912) (see color plate 4), alongside work by Gleizes, Marcel Duchamp, Raymond DuchampVillon, Roger de La Fresnaye, Fernand Leger, and Jacques Villon.5

Picabia’s paintings were textbook examples of the cubist aesthetic circa 1912, which followed the metaphysical tenets of the French philosopher Henri Bergson. Briefly, Bergson argued that the conventional scientific view of the world—which filtered perception through clock time, Newtonian physics, and Euclidian geometry—was a false-hood. Developing a metaphysics to counter it, he posited that the true state of matter could only be grasped through a suspension of the intellect so as to open us to in-tuition. According to Bergson, artists were more capable than others of entering into a sympathetic, intuitive relationship with the world, a claim that was also trumpeted by Gleizes and the cubists, who based their style on these principles.6

Image Not Available

Francis Picabia, Portrait d’une Jeune Fille Américaine dans 1’état de Nudité. 291, nos 5-6, July-August 1915. © Estate of Francis Picabia / SODRAC (2006).

Francis Picabia, ca 1913. Photograph.

In Time and Free Will (1889), Creative Evolution (1907), and other works, Bergson argued that matter was actually energy in a condition of flux and interpenetration and that each moment in time was qualitatively different from the last, like the condition of matter itself. This was the reality that cubism depicts. In Picabia’s Dances at the Spring, for example, the dancers’ bodies appear to break up and merge with their surroundings because the painter is trying to represent the dynamism of matter in space and time as filtered through his artistic intuition.7

So things stood in 1912. However, upon arriving in New York, Picabia made a dramatic break with the cubist movement. As recorded by Hutchins Hapgood in an interview for the Globe newspaper, Picabia argued that the artist’s role was not to “mirror the external world” but rather “to make real, by plastic means, internal mental states.”8 Picabia explained that he could no longer follow cubism because the cubists were “slaves to the strange desire to reproduce” the external world, just like the old masters whose works hung in the dusty halls of the Louvre.9

While his cubist paintings were on exhibit in the Armory Show, he began working in a new “post-cubist” style.10 This was an “unfettered, spontaneous, ever-varying means of expression in form and color waves,” painted “according to the commands, the needs, the inspi-ration of the impression, the mood received.”11 The results—sixteen watercolors, including New York Perceived Through the Body (1913)—were exhibited at a one-man show (with catalogue) which opened at Steiglitz’s 291 gallery on March 17, two days after the New York leg of the Armory Show closed.12 In a special catalogue statement summing up his new aesthetic, Picabia claimed to be unleashing “the mysterious feelings of his ego.” An article on “The Latest Evolution in Art and Picabia” published in Stieglitz’s in-house journal, Camera Work, went further. Here, his style was characterized as “the real Anarchy, needed and foreseen.”13

What prompted Picabia to reject cubism in favor of abstraction? The impetus can be traced to a second ex-cubist, Marcel Duchamp. In the summer of 1912, Duchamp left Paris for Munich, where he studied Max Stirner’s anarchist-individualist manifesto, The Ego and Its Own, a materialist critique of metaphysics and an assertion of libertarian individualism.14 Stirner argued that the metaphysical thinking underpinning religion and notions of truth laid the foundation for the hierarchical division of society into those with knowledge and those without. From here, an entire train of economic, social, and political inequalities ensued, all of which were antithetical to anarchism.15 Combatting metaphysics, Stirner countered that ideas are indelibly grounded in our corporal being. The egoist, therefore, recognized no metaphysical realms or absolute truths separate from experience. Indeed, Stirner deemed the very notion of an “I” to be a form of meta-physical alienation from the self. Libertarian “egoism,” Stirner wrote, “is not that the ego is all, but the ego destroys all. Only the self-dissolving ego . . . the finite ego, is really I. [The philosopher] Fichte speaks of the ‘absolute’ ego, but I speak of me, the transitory ego.”16 Once conscious of its freedom, this self-determining, value-creating ego inevitably came to a “self-consciousness against the state” and its oppresive laws and regulations.17 As Stirner put it, “there exists not even one truth, not right, not freedom, humanity, etc., that has stability before me, and to which I subject myself.”18 He concluded:

I am the owner of my might, and I am so when I know myself as unique. In the unique one the owner himself returns into his creative nothing, out of which he is born. Every higher essence above me, be it God, be it human, weakens the feeling of my uniqueness, and pales before the sun of this consciousness. If I concern myself for myself, the unique one, then my concern rests on its transitory, mortal creator, who consumes himself, and I may say: I have set my affair on nothing.19

Years later, Duchamp related that reading Stirner in Munich brought about his “complete liberation.”20 He and Picabia were very close, and upon returning to Paris that fall, they likely discussed Stirner’s ideas at length.21 In any event, scarcely three months later, Picabia was introducing New Yorkers to “the mysterious feelings of his ego” in free-flowing expressions “cut loose” from cubist “convention” and its “established body of laws and accepted values.”22

If Stirnerist egoism pushed Picabia to adopt a new expressive style, it also, evidently, reinforced his predilection for challenging the statist and religious mores of his day: Picabia was an archhedonist who engaged in numerous extra-marital affairs and excessive drug taking. “He went to smoke opium almost every night,” Duchamp later re-called, “[and] I knew that he drank enormously too.”23 This hedonism would take a decidedly political turn after Picabia returned from New York.

For example, in 1913, he lent his name to anarchist-led protests in Paris against the censorship of a newly unveiled monument at the famous Père Lachaise cemetery honoring the era’s most notorious homosexual, Oscar Wilde (1854-1900). Objecting to the monument’s prominent genitalia and the very idea that a disgraced homosexual merited any memorial, officials had covered the statue with a tarpaulin and fixed a metal plate over the offending organ. In response, a group of Parisian-based anarchist-individualist artists who called themselves the Artistocrats mounted a campaign in defence of the monument. Writing in their journal Action d’art, they celebrated Wilde’s sexuality as a healthy expression of egoist anarchism and condemned the censors as sex-negative perverts whose prudery went against the laws of nature. They also published a full-page anti-censorship statement with Picabia’s name listed among its signatories.24

Picabia was shortly to marshal his own protest against the same censorious forces besieging the Wilde monument. His first full-scale exercise in artistic “egoism” upon returning from New York was an attack on the repression of sexual impulses under the moral regime of Catholicism. The imposing canvas, the enigmatically titled Edtaonisl (Ecclesiastic) (see color plate 5), was exhibited at the Autumn Salon of November 1913. The painting’s subject was a Dominican priest whom Picabia had witnessed during the sea voyage to New York furtively watching the rehearsals of a Parisian exotic dancer.25

Asked to explain his painting, Picabia related that he had fused impressions of the “rhythm of the dancer, the beating heart of the clergyman, the bridge [of the ocean-liner] ... and the immensity of the ocean.”26 Here, Picabia echoed a central tenet of Stirner’s philosophy: that the idealist notion of a “soul” separate from the body fostered self-alienation and the suppression of our natural desires and pleasures.27 Rooted in sensation, his painterly critique of alienation played havoc with artistic conventions, metaphysical idealism, and the priest’s vow of chastity. Thus, he brought the moral cornerstone of Catholicism into disrepute while at the same time leaving critics dumbstruck be-fore one of modernism’s earliest examples of full-blown abstraction.28

When World War I began in August 1914, Picabia was conscripted, but initially avoided the trenches by arranging enlistment as a chauffeur for a French cavalry general behind the lines, first at Bordeaux and then Paris. Increasingly endangered by the war’s progression (he was deemed fit for the infantry), he next secured an assignment as an army purchasing agent and was sent overseas in the summer of 1915 to procure supplies in the Caribbean.29 Promptly abandoning his mission upon reaching New York in June 1915, he reconnected with de Zayas, who had just launched the satiric avant-garde monthly 291 that March. While still in Paris, Picabia had contributed Girl Born Without a Mother (ca 1915), a loosely sketched depiction of rods and springs erupting in ill-defined activity, to 291’ June 1915 issue. This was followed in the July-August edition by the five meticulously executed “object portraits,” including the drawing of a spark plug, Portrait of a Young American Girl in a State of Nudity (1915), mentioned at the beginning of this chapter.30

Read sequentially, the portraits are witty and sometimes caustic commentaries on the personalities associated with de Zayas’ journal. The portrait gracing the cover of 291, for example, is a broken camera with lens extended, whose bellows has become detached from the armature and is collapsing. Attached to the side of the camera is an automobile brake set in park, and a gearshift resting in neutral. The lens strains toward the word “Ideal” printed above it in Gothic script; beside the apparatus is stenciled, Here, This is Steiglitz / Faith and Love (1915). Steiglitz, whom Picabia had befriended during his first New York excursion in 1913, had a long history of opposing modern art’s commercialization, which he feared would compromise the artist’s creative integrity. For over a decade he had run his gallery as a non-commercial venue where New Yorkers could gain exposure to modern photography, sculpture, and painting and, if Steiglitz deemed them sincere in their admiration, purchase a work at prices that varied widely according to the means of the admirer and other considerations.31 Picabia had exhibited at this gallery and was intimately familiar with its workings, as was de Zayas. Indeed, de Zayas had named his journal after Steiglitz’s gallery to signal his allegiance to the latter’s ideals; however, by the summer of 1915, he was rethinking his position.

De Zayas saw a need for a more conventional approach, believing modernists of quality could maintain their independence regardless of commercial pressures if their art was effectively promoted by sympathetic professionals who respected their freedom and paid them well for sales. When Picabia arrived in New York, he joined the debate on the side of de Zayas and as a result, a rift developed. By July, de Zayas had decided to usurp the preeminence of Steiglitz’s project and embark on a new venture, to be located in midtown Manhattan and christened the “Modern Gallery” (the gallery eventually opened in October 1915).32 Exasperated by Steiglitz’s continuing hostility, Picabia and de Zayas evidently called him to account. The July-August cover of 291 suggested Steiglitz’s efforts to popularize modernism on his terms were as exhausted as a broken camera. It was also a potshot at propriety: the sagging bellows resemble a slackened and impotent penis, incapable of achieving an erection.33

Inside the journal were four more drawings. The first, a self-portrait, was a car horn entitled The Saint of Saints—This is a Portrait About Me (1915). The horn is positioned against what appears to be an automobile cylinder and spark plug depicted in cross-section; Picabia loved fast cars and here he is, blowing his own horn as the avant-garde artist who is more “advanced” than anyone else. The horn was followed by the spark plug rendering Portrait of a Young Girl in a State of Nudity, which referred to artist Agnes Ernst Meyer’s role as the “spark” that had started the journal by agreeing to bankroll it behind the scenes. The next portrait, De Zayas, De Zayas! (1915), plays on the editor’s vision in founding a journal devoted to satire. It consists of electrical wiring linking an improbable ensemble of objects—a corset, automobile headlights, an electrical post, and a gyrating mechanical device—all of which “work” to create illumination. The final portrait, Voila Haviland the Poet as He Sees Himself (1915), depicts his friend Paul Haviland as an electric lamp with no plug; earlier, in June of that year, the Franco-American Haviland had been forced to “unplug” himself from participating in 291 following a summons from his father to at-tend to the family business in France. These insular references would have eluded most of 291’ readers; they have only come to light thanks to painstaking art historical research.34

In an interview for the New York Tribune in October 1915, Picabia described his new portrait style as revelatory, relating that upon disembarking in New York, he had been struck by America’s “vast mechanical development.” “I have enlisted the machinery of the modern world, and introduced it into my studio,” he provocatively argued, be-cause “the machine” is “more than a mere adjunct to life. It is really a part of human life—perhaps its very soul.”35

Ascribing such significance to machines underlines the multifaceted complexity of Picabia’s new style, in which he furthered his rejection of cubism and his hostility toward censorious social institutions in a critique with America as its cipher. This was a remarkable exercise in artistic iconoclasm, but to grasp its ramifications, we need to examine Young American Girl more closely from a cubist perspective.

As we have seen, the cubists trumpeted their style as the product of an intuitive, anti-intellectual, and qualitative experience of reality. They even went so far as to equate a cubist artwork, born of qualitative experience, to a living organism.36 The antithesis of qualitative perception was the utilitarian state of mind, which quantified, ordered, and standardized nature. According to Bergson, this type of thinking was unartistic, but could nonetheless provide occasion for a distinctive kind of artistry, namely the comic; this is the theme of his book Laughter (1900), which analyzed humor’s relation to our lesser utilitarian minds.

Bergson’s thesis focused on moments of disjuncture when manifestations of living, organic, qualitative being get mixed up with the in-organic, quantitative, and lifeless. He characterized the type of being that is the antithesis of a living entity as “readymade” and “mechanical.” “The attitudes, gestures, and movements of the human body,” he wrote, become laughable in “exact proportion as the body reminds us of a mere machine.”37 Contrasts of automatism with natural movement, “the rigid, ready-made, and mechanical” with “the supple, ever-changing, and living,” were “the defects that laughter singles out.”38 Here, we find one of the satirical themes in Young American Girl and the other object portraits; Picabia drew on Bergson’s thesis concerning humor to mount what was, in effect, a parody of cubism.

A cubist portrait was understood to be an artistic exercise of profound sympathy, in which the artist captured the sitter’s unique personality through a process of intuition attuned to the life force of the subject, right down to her material dynamism. To quote Gleizes and Metzinger in Cubism, by circumnavigating the intellect, the artist created a “sensitive passage between two subjective spaces” in which “the personality of the sitter” was “reflected back upon the understanding of the spectator.”39 As such, the painting was a unique expression of a unique moment in the creative evolution of both the artist and the subject.

Picabia’s Young American Girl is the antithesis of this. It is, in cubist terms, completely art-less, lacking in emotion, empathy, or originality: or rather, it is a parodic inversion of Bergsonian cubist values, an exercise in mimicry that apes the painterly idealism it critiques in its guise as a humorous joke. To cite Bergson:

Whether we find reciprocal interference of series, inversion, or repetition, we see that the objective in comedy is always the same—to obtain what we have called a mechanization of life. You take a set of actions and relations and repeat it as it is, or turn it upside down, or transfer it bodily to another set with which it partially coincides—all these being processes that consist in looking upon life as a repeating mechanism, with reversible action and interchangeable parts.40

Cubism is made fun of, but this is not the only target. What, for instance, was Picabia saying about the United States when he represented Americans, including a “young girl,” as machines? I would argue he was passing judgment, and that his assessment is less than flattering. Taking his comments to the New York Tribune reporter as our starting point, Picabia suggests that Americans are distinguished as a nation by an advanced state of industrialism, which dominates them to such a degree that machine qualities have invaded their very souls, so to speak. Thus, Picabia inverts cubism’s metaphysical reading of what it is to be human in order to clear the ground for addressing the culture of the United States critically. And through this elliptic process of mirroring he comments not only on its industrial prowess, but also on the mass marketing that drives it. Picabia’s young American girl is a diagrammatically drawn spark plug—the sort of thing one could find in any auto-parts catalogue, newspaper, or magazine advertisement.41 However, if this is advertising, what of its content? Stripped of art’s aura, the patina of beauty encapsulated by the girl’s “state of nudity” implied something else: a marketing ploy that pointed to the portrait’s encoded satiric function as sexual provocation.

This sexual stamp had Parisian roots. In all likelihood it was inspired in part by Supermale (1902), a satirical (and certainly by American standards, obscene) novel by the French satirist Alfred Jarry.42 Jarry’s book tells the story of an American scientist who creates a “perpetual motion food” which allows for, among other things, non-stop sex. In a challenge to her father, the scientist’s young daughter—“a little slip of a girl”—demonstrates that she can achieve the same results through sheer force of will. The object of her affections is a machine-like “super-male” who is abnormally lacking in emotion. After a lengthy performance with the young girl, he dies while hooked up to another of her father’s inventions, a love-inspiring machine.43

The Jarryesque subtext of Picabia’s Young American Girl, then, is its tongue-in-cheek presentation of feminine sexual allure Americanized, industrialized, and commercialized. Think of this portrait as a satire of American advertising in which Picabia shamelessly parades a young girl for sale in a “state of nudity” with a standard manufacturer’s guarantee—FOR-EVER—of flawless performance in perpetuity. Certainly, this latter feature is what caught the attention of the 291 circle. In an accompanying article on the object portraits, de Zayas wrote that modern art could only succeed in the United States if it adopted the features of commercialism—and then praised Picabia for inventing such an art.44

More to the point, Picabia had created an artistic means of attacking this commercialism on its own turf. Young American Girl was a slap in the face of the puritanical artistic values underpinning the mass marketing of modern American femininity. In the early twentieth century, popular magazines and advertisements were filled with unsullied but curvaceous full-bodied beauties such as J.C. Leyendecker’s vacationing golfers or popular magazine illustrator Howard Chandler Christy’s virginal American Girl (1912), from his “Liberty Bells” series. In the minds of both publishers and the general public, such idealizations made the marketing of femininity respectable, even aesthetically and culturally uplifting.45

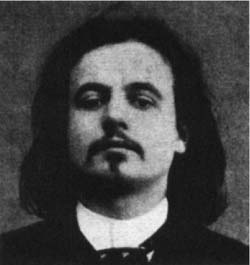

Alfred Jarry, 1896. Photograph by Felix Nadar.

Picabia’s version of commercialized womanhood mirrored and mocked American marketing by stripping its prototype Young American Girl down to her “essence” as a sexual commodity for sale. Here, the politics of censorship make their entrance, because Picabia’s portrait can also be read as a challenge to the repressive anti-obscenity laws which were at the time regulating American artistic production, both high and low.

The spearhead of censorship was Anthony Comstock, Special Agent for the United States Postal Office and chief investigator for the New York Society for the Repression of Vice, an organization em-powered to arrest and charge anyone in possession of literature, photographs, or artwork it judged to be obscene.46 From 1873, when the Federal obscenity law (“The Comstock Act”) was passed, Comstock and his agents had full power to search premises and seize materials at will. In the first two years alone, over 194,000 pictures and photo-graphs were confiscated and destroyed under their watch. At the same time, anti-vice organizations and state laws against vice mushroomed around the country.47

Art was not immune from the onslaught. One of Comstock’s earliest raids targeted a fashionable New York art gallery for distributing reproductions of “objectionable, lewd, and obscene” work by “the modern French School” (the works in question were nudes by well-known French academics such as William-Adolphe Bouguereau).48 The repressiveness was such that by 1895, no less a figure than Kenyon Cox of the conservative New York Academy of Design was complaining bitterly about it.49 The illustration beauties of American commercial art, therefore, reflected more than native prudishness: they were carefully calibrated to sell a product while remaining firmly within the boundaries of what the censors deemed respectable.

Howard Chandler Christy, The American Girl, Liberty Belles, 1912. Oil on canvas.

When did censorship in the United States become a concern of Picabia’s? As we have seen, upon returning to France in the summer of 1913, he had challenged censorious moralizing in his own country by signing the petition in support of the Wilde monument and exhibiting the anti-clerical Edtaonisl that November. Earlier still, however, he was involved in another obscenity controversy. In March 1913, while Picabia was in New York, the Armory Show traveled to the Chicago Art Institute, where conservatives reacted by filling the press with letters and articles condemning the exhibition, in particular calling the room given over to the French cubists “obscene,” “lewd,” “immoral,” and “indecent.”50 Chicago’s anti-vice Law and Order League called for the exhibition’s closure, and civic figures such as clergymen and high school instructors concurred.51 The mayor of Chicago even joined the bandwagon by visiting the exhibition, where he singled out Picabia’s Dances at the Spring and made fun of it in the company of reporters.52

Finally, in early April, the Illinois Senate sent a vice investigator to examine the artwork. In a front-page news story for the Chicago American, the investigator declared cubism to be “lewd” and feared for its “immoral effect on other artists.”53 Based on the investigator’s report, the State Lieutenant Governor ordered the Illinois Senate’s anti-vice “White Slave Commission” (white slavery was a popular term for prostitution) to determine whether or not the art was “harmful to public mores” (in the end the exhibit was allowed to continue).54 The level of hostility was so intense that the alarmed New York organizers published a hastily compiled pamphlet entitled For and Against, which reprinted, among other items, a statement by Picabia that had accompanied his “post-cubist” exhibition at Steiglitz’s 291 gallery.55

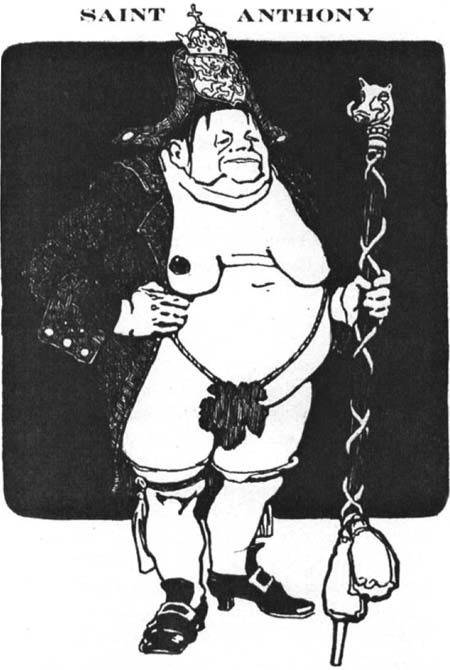

Recall that when this scandal reached its boiling point in early April, Picabia was spending considerable time with the journalist Hutchins Hapgood. Hapgood was a member of the Free Speech League, an organization founded in 1902 with the express purpose of challenging Comstock and the anti-obscenity laws.56 Picabia might well have discussed the Armory Show’s reception in Chicago with Hapgood or, for that matter, with any of the artists and critics in the Steiglitz circle. The depths of their pro-vice contempt for censorship are ably summed up in a caricature published in The Revolutionary Almanac (1914) by Hippolyte Havel, a friend of Steiglitz and Hapgood who also knew Picabia.57 Entitled Saint Anthony, Guardian of Morals (ca 1914), the illustration accompanies a story in which Comstock muses on the trials of life in a world of “nudity and shamelessness,” where “good and chastity” go unrewarded while those with “neither conscience nor care” feast on “sinful life’s joys.” Frustrated by this state of affairs, he dreams of overthrowing God—who has evidently acquired a taste for vice—in order to decree that the entire universe be surveyed, from dawn to sunset, by a censoring army of “emissaries, spies, and detectives.”58 One can well imagine Picabia chortling at the joke.

In 1915, the Chicago events of two years earlier might have seemed like a distant memory were it not for the fact that in March, just a few months before Picabia’s arrival in June, none other than Comstock himself again raised the hackles of New Yorkers by raiding an art exhibition at a popular Greenwich Village restaurant run by Havel and his lover Polly Holiday.59 The art in question was a series of nudes by Clara Tice, a young artist who had studied under the anarchist painter Robert Henri.60 During the raid, outraged patrons blocked Comstock’s officers until one of them, Alan Norton, editor of an ir-reverent monthly magazine entitled Rogue, announced that he was purchasing the entire collection on the spot.61 This threw a wrench into Comstock’s rights of seizure and brought the raid to an end, though charges were laid.

THE GUARDIAN OF MORALS

Saint Anthony, The Guardian of Morals, ca 1914. From Hippolyte Havel, ed., The Revolutionary Almanac, 1914.

The incident got front-page coverage the next day in the New York Tribune and rekindled the New York modernists’ fight against Comstock’s censorious regime.62 In May and July of 1915, the art promoter and publisher Guido Bruno defied the law by mounting two exhibitions in his Greenwich Village gallery featuring drawings of nudes by Tice.63 In the wake of her subsequent trial (and acquittal) on obscenity charges in September, he staged a mock court event where Tice defended herself before a cross-section of New York’s avant-garde.64 By the time Picabia arrived in New York, therefore, the Tice affair would very likely have caught his attention, given his past encounters with the American drive to suppress “vice” during the Armory Show.

Let us return, then, to Picabia’s Young American Girl and consider it more closely from this perspective. In her 1997 study Suspended License, Elizabeth Childs has observed that “the history of censorship is not just a matter of institutional solutions to embarrassing or threatening art; it is also a history of individual artistic decisions made in the face of such policies.”65 Childs enumerates a range of artistic responses to such repression, from self-censorship to avoid persecution to courting it by breaking the rules anyway. And then there are the more subterranean tactics of “working inside or around a censorious art system.” “These tactics,” she writes, “include changing the venue for the exhibition of the work; changing the image itself; changing the context for viewing the work; appearing to follow the rules while en-coding prohibited sentiment in art; or perhaps the most effective ploy, turning the tables and attacking the censoring institution through the art itself.”66

Young American Girl encodes and attacks. Read as a brazen “advertisement” of a young girl’s naked sexuality, the portrait is nothing less than a pornographic outrage worthy of the severest prosecution. Yet it isn’t, literally—one has to interpret it as such. Here, Picabia echoed one of the most telling accusations American radicals leveled against Comstock—pornography is in the mind of the beholder. Furthermore, in the course of doing so, he exposed the hypocrisy undergirding American censorship. The nakedness of this portrait was all about “marketing the product”; thus, in one fell swoop, Picabia put the lie to the puritanical grease facilitating the capitalization of sex for profit. Here, Bergson gets the last word. In Laughter, he speculated:

Might not certain vices have the same relation to character that the rigidity of a fixed idea has to intellect? Whether as a moral kink or a crooked twist given to the will, vice has often the appearance of a curvature of the soul. Doubtless there are vices into which the soul plunges deeply with all its pregnant potency, which it rejuvenates and drags along with it into a moving circle of reincarnations. These are tragic vices. But the vice capable of making us comic is, on the contrary, that which is brought from without, like a ready-made frame into which we are to step. It lends us its own rigidity instead of borrowing from us our flexibility. We do not render it more complicated; on the contrary, it simplifies us.67

Whereas America was vice-ridden in the worst sense, Picabia was vice-ridden in the best sense. His subtle and mercurial ego, untouched by vice’s “tragic” aspect, deployed the humorous side of the equation by way of parodying the “moral kink” of Comstockery as a mechanical simplification in a “readymade frame”: Portrait of a Young American Girl in a State of Nudity.

If we read Picabia’s object portraits as a straightforward embrace of things American, we are missing the point. Certainly, he introduced a new field of expression to art in the United States, but he did so in solidarity with anarchist currents of dissidence decidedly at odds with the establishment values that claimed purchase on America. In other words, the advent of Dada in New York was as much a political event as an artistic one.

1 Rudolf E. Kuenzli, “Introduction,” New York Dada, Rudolf E. Kuenzli, ed. (New York: Willis Locker and Owens, 1986): 2-3.

2 Wanda Corn, The Great American Thing: Modern Art and National Identity, 1915-1935 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999): 64-66.

3 On Picabia and Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia’s visit, see the leading authority on New York Dada, Francis M. Naumann, New York Dada (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994): 19-20.

4 The leading role of Gleizes is discussed in Mark Antliff, Inventing Bergson: Cultural Politics and the Parisian Avant-Garde (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993): passim.

5 See the catalogue listings of works exhibited in The Armory Show 50th Anniversary Exhibition (New York: Clarke and Way, 1963): 190, 200.

6 On cubist aesthetics as codified by Gleizes and Metzinger, see Antliff, Inventing Bergson, 39—66.

7 Ibid., 46-48.

8 Hutchins Hapgood, “A Paris Painter,” New York Globe, February 20, 1913, 8.

9 “Picabia, Art Rebel, Here to Teach New Movement,” New York Times (February 16, 1913): sect. 5, 9.

10 The style was destined to stir considerable controversy. See Ineana B. Leavens, From “291” to Zurich: The Birth of Dada (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1983): 74-75.

11 “A Post-Cubist’s Impressions of New York,” New York Tribune (March 9, 1913): part 11, 1.

12 The exhibition ran from March 17 to April 5.

13 The preface was reprinted as “Cubism by a Cubist: Francis Picabia in the Preface to the Catalogue of his New York Exhibition,” For and Against: Views on the International Exhibition held in New York and Chicago, Frederick James Gregg, ed. (New York: Association of American Painters and Sculptors, Inc., 1913): 45. See also Maurice Aisen, “The Latest Evolution in Art and Picabia,” Camera Work, Special Number (June 1913): 21.

14 Stirner’s influence is discussed in Francis M. Naumann, “Marcel Duchamp: A Reconciliation of Opposites,” Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century, Rudolf E. Kuenzli and Francis M. Naumann, eds. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989): 29-32.

15 Max Stirner, The Ego and Its Own (London: A.C. Fifield, 1915): 180-190; 473.

16 Ibid., 237.

17 Ibid., 361.

18 Ibid., 463

19 Ibid., 490.

20 Naumann, “A Reconciliation of Opposites,” 29.

21 For example, Duchamp and Picabia might have conversed about Stirner during a trip to Jura, France in October of that year, just prior to Picabia’s trip to the United States. The Jura trip is discussed in William A. Camfield, Francis Picabia: His Art, Life and Times (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1979): 35.

22 “A Post- Cubist’s Impressions of New York,” 1.

23 Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp (New York: Da Capo, 1987): 32.

24 Mark Antliff, “Cubism, Futurism, Anarchism: The ‘Aestheticism’ of the Action d’art Group, 1906-1920,” Oxford Art Journal no. 21 (1998): 109.

25 Virginia Spate, Orphism: The Evolution of Non-Figurative Painting in Paris, 1910-1914 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978): 328.

26 Camfield, 61.

27 The mind-body fusion is the basis for Stirner’s materialist critique of the “soul”—a self-alienating concept used by Christianity to suppress our sensual inclinations. See Allan Antliff, Anarchist Modernism: Art, Politics, and the First American AvantGarde (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001): 77; Stirner, 451-453.

28 The critical reception is discussed in Camfield, 59.

29 Ibid., 71.

30 Naumann, New York Dada, 59-60. According to Michel Sanouillet, the first three issues of 291 (March, April, May) were mailed to Picabia in Paris, and he created his drawing at the request of de Zayas for inclusion in the June issue. Michel Sanouillet, “Picabia’s First Trip to New York,” Dada New York: New World for Old, Martin Ignatius Gaughan, ed. (New York: G. K. Hall, 2003): 118.

31 I discuss the exploitive commercial pressures on American modernists and various attempts to overcome them in Antliff, Anarchist Modernism, 24; 32-33; 54-55.

32 Marius de Zayas, How, When, and Why Modern Art Came to New York, Francis M. Naumann, ed. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996): 90-96.

33 Richard Whelan, Alfred Steiglitz: a Biography (New York: Little, Brown, 1995): 348-349.

34 Naumann, New York Dada, 60-61.

35 “French Artists Spur on an American Art,” New York Tribune (October 24, 1915): 2.

36 Antliff, Inventing Bergson, 35.

37 Henri Bergson, Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic (1900) in Comedy, Wylie Sypher, ed. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press): 79.

38 Ibid., 145.

39 Gleizes and Metzinger, Cubism quoted in Antliff, Inventing Bergson, 48.

40 Bergson, 126.

41 William Innes Homer has traced Picabia’s advertisement sources. See William Innes Homer, “Picabia’s ‘Jeune fille américaine dans I’etat de nudite’ and ‘Her Friends’,” Art Bulletin 58 (March 1975): 110-115.

42 Linda Henderson, Duchamp in Context: Science and Technology in the Large Glass and Related Works (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998): 47-51.

43 Alfred Jarry, The Supermale (New York: New Directions, 1977).

44 Maurice de Zayas, “New York At First Did Not See,” 291 5-6 (July-August 1915): n.p.

45 In her exhaustive study of such representations, Martha Banta singles out Christy’s series as the prototype ideal. Martha Banta, Imagining American Women: Idea and Ideals in Cultural History (New York: Columbia University Press, 1987): 206-211.

46 Nicola Beisel, Imperiled Innocents: Anthony Comstock and Family Reproduction in Victorian America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997): 3.

47 Jane Clapp, Art Censorship: A Chronology of Proscribed and Prescribed Art (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1972): entry 1874 (b), 151.

48 Ibid., entry 1887, 160-161. Some of the artists are listed in Nicola Beisel, Imperiled Innocents: Anthony Comstock and Family Reproduction in Victorian America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997): 168.

49 Kenyon Cox to Mr. Fraser, April 2, 1896, Century Collection, Manuscripts Division, New York Public Library.

50 See, for example, “May Bar Youngsters From Cubists Show,” Chicago Record Herald (March 27, 1913): 22; “Art Institute Censured by Pastor for Display of ‘Vulgar’ Pictures,” Chicago Record Herald (April 8, 1913): 9.

51 Milton W. Brown, The Story of the Armory Show (New York: Abbeville Press, 1988): 208-209.

52 “’I See It’” Says Mayor at Cubist Art Show,” New York Herald (March 28, 1913): 9.

53 “Cubist Art Called Lewd: Investigator for Senate Vice Commission Fears Immoral Effect on Artists,” Chicago American (April 3, 1913): 1.

54 “Slave’s Commission to Probe Cubist Art,” The Inter-Ocean (April 2, 1913): 10. Reporters who were invited along recorded that Picabia’s Dancers at the Spring was again singled out for derisive comment during the commission’s visit; “Art of Cubists Staggers Critics in State Senate,” The Inter-Ocean (April 3, 1913): 1.

55 Picabia, “Cubism by a Cubist,” 45-48.

56 Hutchins Hapgood, A Victorian in the Modern World (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1939): 279. The League’s founding and activities leading up to World War I are discussed in David M. Rabban, Free Speech in Its Forgotten Years, 1870-1920 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997): 44-64.

57 Antliff, Anarchist Modernism, 97-99.

58 “The Confiscated Picture,” The Revolutionary Almanac, Hippolyte Havel, ed. (New York: Rabelais Press, 1914): 70-71.

59 Marie T. Keller, “Clara Tice, ‘Queen of Greenwich Village,’” Women in Dada: Essays on Sex, Gender, and Identity, Naomi Sawelson-Gorse. ed. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998): 414. On Havel and Holiday see Antliff, Anarchist Modernism, 80.

60 Keller, 415.

61 Ibid., 414.

62 Ibid., 417-418.

63 Ibid., 414.

64 Ibid., 418.

65 Elizabeth C. Childs, “Introduction,” Suspended License: Censorship and the Visual Arts, Elizabeth C. Childs, ed. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997): 15.

66 Ibid., 16.

67 Bergson, 69-70.