A CONSTITUTION may be altered by means of (1) a formal amendment process; (2) periodic replacement of the entire document; (3) judicial interpretation; and (4) legislative revision. What difference does it make if we use one method rather than another? What is the relationship between these four methods? What do we learn about the constitutional system and its underlying political theory by the pattern of choice among these alternatives? These are some of the questions I shall address below.

It is true that a constitution is often used as ideological window dressing; and even in places where constitutions are taken very seriously, these documents fail to describe the full reality of an operating political system. Yet it is also true that today hardly any political system, dictatorial or democratic, fails to reflect political change in its respective constitution. Constitutions may not describe the full reality of a political system, but when carefully read they are windows into that underlying reality.

This essay is an initial attempt to use a critical, if often overlooked constitutional device—the amendment process—as a window into both the reality of political systems and the political theory or theories of constitutionalism underlying them. The method will be systematic, comparative, and, to the extent possible, empirical. We will begin with a brief overview of the theoretical assumptions that underlay the formal amendment process when it was invented; we will then identify a number of theoretical propositions concerning the amendment process and look for patterns in the use of the amendment process that can help us create empirical standards upon which to erect a theory of constitutional amendment.

The modern written constitution, first developed in English-speaking North America, was grounded in a doctrine of popular sovereignty.1 This belief in the people as the ultimate source of power was, from the European viewpoint, a startling innovation of either momentous or monstrous importance—depending upon whether the European was a republican or a monarchist. Even though many in Britain were skeptical at best, Americans did not regard popular sovereignty as an experimental idea, but rather one that stood at the very heart of their shared political consensus.2 American political writing had used the language of popular sovereignty even before Locke’s Second Treatise was published, and the early state constitutions of the 1770s contained clear and firm statements that these documents rested upon popular consent.3

Although the theory of popular sovereignty was well understood in America by 1776, the institutional implications of this innovative doctrine had to be worked out in constitutions adopted over the next decade. Gradually it was realized that a doctrine of popular sovereignty required that constitutions be written by a popularly selected body other than the legislature, which Americans labeled a convention, and then ratified through a process that elicited popular consent—ideally in a referendum. This double implication was established in the process used to frame and adopt the 1780 Massachusetts and 1784 New Hampshire constitutions, although the referendum portion of the process did not become standard until the nineteenth century. Americans moved quickly to the conclusion that if a constitution rested upon popular consent, then the people could also replace it with a new one. John Locke had argued that the people could replace government, but only when those entrusted with the powers of government had first disqualified themselves by endangering the happiness of the community to such a degree that civil society could be said to have reverted to a state of nature.4 The Americans went well beyond Locke, and his chief interpreter, William Blackstone, by institutionalizing constitutional change while still in civil society, which is to say whenever they wanted. It is of considerable importance that they included not only the replacement of a constitution, but also its formal amendment.

The first new state constitution in 1776, that of New Jersey, contained an implicit notion of amendment, but the 1776 Pennsylvania document contained the first explicit amendment process—one that used a convention process and bypassed the legislature.5 By 1780 almost half the states had an amendment procedure, and the principle that the fundamental law could be altered piecemeal by popular will was firmly in place.

In addition to popular sovereignty, the amendment process was based on three other premises central to the American consensus in the 1770s—an imperfect but educable human nature, the efficacy of a deliberative process, and the distinction between normal legislation and constitutional matters. The first premise held that humans are fallible, but capable of learning through experience.6 Americans had long considered each governmental institution and practice to be in the nature of an experiment. Since fallibility was part of human nature, provision had to be made for altering institutions after experience revealed their flaws and unintended consequences. Thus the amendment process was predicated not only on the need to adapt to changing circumstances, but also on the need to compensate for the limits of human understanding and virtue.

A belief in the efficacy of a deliberative process was also part of the general American constitutional perspective. A constitution was viewed not as a means to arrive at collective decisions in the most efficient way possible, but to arrive at the best possible decisions in pursuit of the common good under a condition of popular sovereignty. The common good is a more difficult standard to approximate than the good of one class or a part of the population, and the condition of popular sovereignty, even if operationalized as a system of representation, requires the involvement of many more people than forms of government based on other principles. This in turn requires a slow, deliberative process for any political decision, and the more important the decision, the more deliberative the process should be.

Constitutional matters were considered more important in 1789 America than normal legislation, which led to a more highly deliberative process that distinguished constitutional and normal legislative matters. The codification of the distinction in constitutional articles of ratification and amendment resulted in American constitutions being viewed as a higher law that should limit and direct the content of normal legislation.

In sum, the amendment process invented by the Americans was a public, formal, highly deliberative decision-making process that distinguished between constitutional matters and normal legislation, and returned to roughly the same level of popular sovereignty as that used in the adoption of the constitution. The assumptions underlying the amendment idea require that the procedure be neither too easy nor too difficult. A process that is too easy does not provide enough distinction between constitutional matters and normal legislation, thereby violating the assumption of the need for a high level of deliberation and debasing popular sovereignty. One that is too difficult, on the other hand, interferes with the needed rectification of mistakes, thereby violating the assumption of human fallibility and preventing effective recourse to popular sovereignty when necessary.

The literature on constitutions at one time made a distinction between major and minor constitutional alterations by calling the former “revisions” and the latter “amendments.” The distinction turned out in practice to be conceptually slippery, impossible to operationalize, and therefore generally useless.7 It would be more helpful to use “amendment” as a description of the formal process developed by the Americans, and “revision” to describe processes that instead use the legislature or judiciary. Unless we maintain the distinction between formal amendment and revision, we will lose the ability to distinguish competing constitutional theories.

The innovation of an amendment process, like the innovation of a written constitution, has diffused throughout the world to the point where only 5 of the existing 142 national constitutions lack a provision for an amending process.8 However, the diffusion of written constitutions and the amendment idea do not necessarily indicate widespread acceptance of the principles that underlie the American innovation. In most countries with a written constitution, popular sovereignty and the use of a constitution as a higher law are not operative political principles. Any comparative study of the amendment process must therefore first distinguish true constitutional systems from those that use a constitution as window dressing, and then go on to recognize that among the former there are variations in the amendment process that rest on assumptions at odds with those in the American version. Indeed, it is the efficiency with which study of the amending process reveals such theoretical differences that draws us to it.

At the same time, a comparative study of amendment processes allows us to delve more deeply into the theory of constitutional amendment as a principle of constitutional design. For example, we might ask the following questions: What difference does it make when constitutions are formally amended through a political process that does not effectively distinguish constitutional matters from normal legislation? Why might we still want to draw a distinction between formal amendment and revision by normal politics as carefully and as strongly as possible?

One important answer to the question is that the three prominent methods of constitutional alteration other than complete replacement—formal amendment, legislative revision, and judicial interpretation—reflect, in the order listed, a declining commitment to popular sovereignty; and the level of commitment to popular sovereignty may be a key attitude for defining the nature of the political system. However, it is not always possible to tell when popular sovereignty has been abandoned for an elitist alternative. For example, some constitutions by design, and others by accident, leave so much room for interpretation that what some call amendment-through-interpretation is actually specification in the face of ambiguity. That is, those who write constitutions often purposely leave considerable room for interpretation. Formal constitutional provisions may not always define a single-peaked preference—that is, one clear choice that dominates all alternatives—but, rather, a range of acceptable possibilities, all of which may be understood as undergirded by popular sovereignty. As long as interpretation does not move outside a range of possibilities defined by a normal language interpretation of the constitutional provision, even if the operation of the political system is significantly changed as a consequence, there has not really been an amendment but rather a specification of a choice within a range of possibilities. Thus, rather than focusing only upon whether the operation of a political system is changed, we should also consider the range of possibilities permitted by a constitutional provision.

With these considerations and assumptions as background, it is possible to begin the generation of testable propositions that can be used in the construction of a theory of amendment.

Every theory has to begin with a number of assumptions. We have seen how the original American version rested on the assumptions of popular sovereignty, an imperfect but educable human nature, the efficacy of a highly deliberative decision-making process, and the distinction between normal and constitutional law. While these help define the working assumptions of one theory of amendment, albeit the original one, they do not provide a complete basis for describing even the contemporary American theory, let alone a general theory of amendment. We turn now to developing a theory that includes the American version but also accounts for, and provides the basis for analyzing, any version of constitutional amendment.

Our first working assumption has to do with the expected change that is faced by any political system.

ASSUMPTION 1: Every political system needs to be altered over time as a result of some combination of: (1) changes in the environment within which the political system operates (including economics, technology, and demographics); (2) changes in the value system distributed across the population; (3) unwanted or unexpected institutional effects; and (4) the cumulative effect of decisions made by the legislature, executive, and judiciary.

A second assumption concerns the nature of a constitution.

ASSUMPTION 2: In political systems that are constitutional, in which constitutions are taken seriously as limiting government and legitimating the decision-making process they describe, important alterations in the operation of the political system need to be reflected in the constitution.

If these two assumptions are used as premises in a deductive process, they imply a conclusion that stands as a further assumption.

ASSUMPTION 3: All constitutions require regular, periodic alteration, whether through amendment, revision, or replacement.

Revision, as noted earlier, refers to alterations in a constitution through judicial interpretation or legislative action. However, we are initially more concerned with the use of a formal amendment process, and this requires that we develop several concepts for use in our propositions. The first concept is that of amendment rate.

“Amendment rate” does not refer to the number of amendments a constitution has. Rather it refers to the average number of amendments passed per year since the constitution came into effect. Many constitutional scholars criticize constitutions that are much amended.9 However, constitutionalism and the logic of popular sovereignty are based on more than simplicity and tidiness. Any people who believe in constitutionalism will amend their constitution when needed, as opposed to using extraconstitutional means. Thus, a reasonable amendment rate will indicate that the people living under it take their constitution seriously. Furthermore, the older the constitution is, under conditions of popular sovereignty, the more successful it has been, but also the larger the number of amendments it is likely to have. However, it is the rate of amendment that is important, not the total number of amendments.

In sum, a successful constitutional system would seem to be best defined by a constitution of considerable age that has a total number of amendments, which, when divided by the age of the constitution in years, represents a reasonable amendment rate—one that is to be expected in the face of inevitable change. A less than successful constitutional system would seem to be defined by a very high rate of constitutional replacement, an exceptionally high rate of amendment, or an exceptionally low amendment rate.

This raises the question of what constitutes a “reasonable” rate of amendment as opposed to one that is too high or too low. Since we will use a systematic study of actual amendment rates, we hope to illuminate this question empirically rather than in an a priori manner. This means we must initially use a symbolic stand-in for our propositions. Futhermore, since a reasonable rate is likely to be a range of rates rather than a single one, the symbol will represent a range with an upper and a lower boundary such that anything above this reasonable rate is probably too high, and anything below the range too low. We shall use <#> to symbolically represent this reasonable range of amendment rates.

The first proposition is frequently found in the literature, but it has never been systematically verified, or its effect measured.

PROPOSITION 1: The longer a constitution, the higher its amendment rate, and the shorter a constitution, the lower its amendment rate.

Commentators frequently note that the more provisions a constitution has, the more targets there are for amendment, and the more likely the constitution will be targeted because it deals with too many details that are subject to change. While on the one hand this seems intuitively correct, the data that are used usually raise the question of which comes first—the high amendment rate or the long constitution? This is because a constitution’s length is usually given as of a particular year, and not in terms of its original length. So for example, the Alabama Constitution of 1901 had reached the stupendous length of 174,000 words by 1991 and had an extemely high amendment rate of 8.07 per year. Was the constitution long because it had a high amendment rate, or did it have a high amendment rate because it was long to begin with? We will answer this question in the next section using data from American state constitutions. For now it is sufficient to note that the question turns out to be an important one to resolve because the empirical relationship is so strong and consistent that in order to test every other proposition it will be necessary to control for the length of a constitution.

Our second proposition is also a common one in the literature, although it too has never before been systematically tested.

PROPOSITION 2: The more difficult the amendment process, the lower the amendment rate, and the easier the amendment process, the higher the amendment rate.

As obvious as this proposition is, it cannot be tested until one shifts from the number of amendments in a constitution to its amendment rate, and until one develops an index for measuring the degree of difficulty associated with an amendment process. Such an index is presented in the next section as part of what is needed to develop a way of predicting the likely consequences of using one amendment process versus another. Until these consequences can be predicted with some degree of reliability, we cannot sensibly evaluate competing forms of formal amendment in terms of their being too easy or too difficult.

The literature on American state constitutions generally argues that these documents are much longer than the national Constitution because they must deal with more governmental functions. For example, if a constitution deals with matters such as education, criminal law, local government, and finances, it is bound to be more detailed, longer, and thus have a higher amendment rate. From this we can generalize to the following proposition.

PROPOSITION 3: The more governmental functions dealt with in a constitution, the longer it will be, and the higher rate of amendment it will have.

The concept of popular sovereignty was originally developed to justify the replacement of one government by another, and therefore the complete replacement of a constitution is perfectly in accord with the concept. During the bicentennial of the U.S. Constitution much was made of the document’s age—usually to the positive. Our concern here is not to praise or blame either high or low rates of constitutional replacement, but to develop a general theory that will help us understand why a constitution may be altered by replacement instead of by amendment or revision, and what difference it makes. Whether for good or for ill, some political systems replace their constitutions with great regularity while others rarely replace theirs.

It would seem that constitutions are usually replaced for one of three reasons. An abrupt change in regime may leave the values, institutions, and/or implications of the old constitution seriously at odds with those of the people now in charge. Or even without the specific demarcation denoted by the notion of regime change, a society might simply come to feel that the constitution written years before has simply not kept up with a host of important, albeit incremental, changes through time. Finally, the old constitution may have been changed so many times that it is no longer clear what lies under the encrustations, and clarity demands a new beginning. Once again we make use of our “reasonable” rate of amendment.

PROPOSITION 4: The further the amendment rate is from the mean of <#>, either higher or lower, the greater the probability that the entire constitution will be replaced, and thus the shorter its duration. Conversely, the closer an amendment rate is to the mean of <#>, the lower the probability that the entire constitution will be replaced, and thus the longer its duration.

A low rate of amendment in the face of needed change may lead to the development of some extraconstitutional means of revision, most likely judicial interpretation, to supplement the formal amendment process. We can now, on the basis of earlier discussion, generate a string of propositions that will prove useful in a discussion at the end of this essay on theories of constitutional construction.

PROPOSITION 5: A low amendment rate associated with a long average constitutional duration strongly implies the use of some alternative means of revision to supplement the formal amendment process.

PROPOSITION 6: In the absence of a high rate of constitutional replacement, the lower the rate of formal amendment, the more likely the process of revision is dominated by a judicial body.

PROPOSITION 7: The higher the formal amendment rate, (a) the less likely the constitution is being viewed as a higher law; (b) the less likely a distinction is being drawn between constitutional matters and normal legislation; (c) the more likely the constitution is being viewed as a code; and (d) the more likely the formal amendment process is dominated by the legislature.

PROPOSITION 8: The more important the role of the judiciary in constitutional revision, the less likely the judiciary is to use theories of strict construction.

PROPOSITION 9: Reasonable rates of formal amendment and replacement tend to be associated with a belief in popular sovereignty.

After testing Propositions 1 through 4 using data from the American state constitutions, we shall seek further verification by examining the amendment process in nations where constitutionalism is taken seriously and does not serve merely as window dressing. The American state documents are examined first because data on them are readily available and easily comparable and because the similarities in their amendment processes reduce the number of variables that must be taken into account. Moreover, together they constitute about half of human experience with serious constitutionalism.

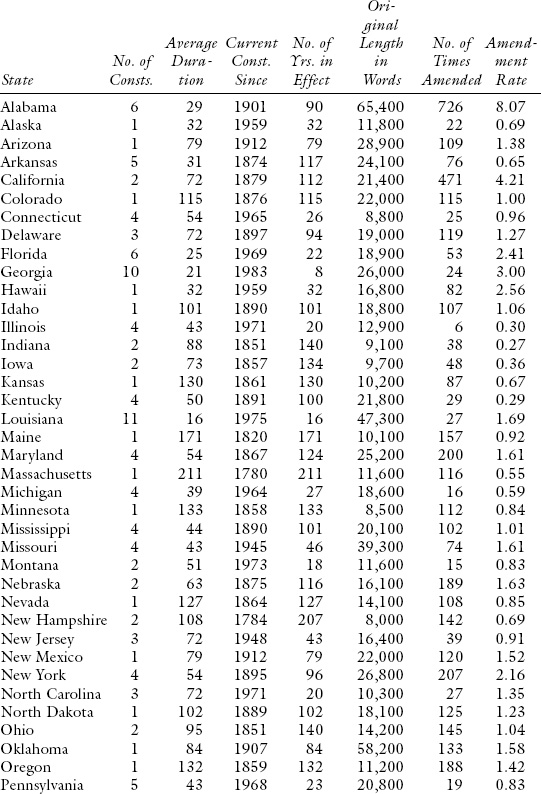

The data in Table 1 provide a state-by-state breakdown on some of the constitutional characteristics that the literature has deemed important, such as a constitution’s length, date of adoption, number of years in effect, and frequency of replacement. We will begin with a consideration of length.

Albert Sturm, one of the most able students of state constitutions, summarizes the literature as seeing state constitutions burdened with (1) the effects of continuous expansion of state functions and responsibilities and the consequent growth of governmental machinery; (2) the primary responsibility for responding to the increasing pressure of major problems associated with rapid urbanization, technological development, population growth and mobility, economic change and development, and the fair treatment of minority groups; (3) the pressure of special interests for constitutional status; and (4) continuing popular distrust of state legislatures resulting from past abuses, which result in detailed restrictions on governmental activity. All of these factors contribute to the length of state constitutions, and it is argued that not only do these pressures lead to many amendments, and thus greater length, but that greater length itself leads to the accelerated need for amendment simply by providing so many targets for change.10 Thus, the length becomes a surrogate measure for all of these other pressures to amend, and is a key causal variable.

Table 1 shows that the average amendment rate is much higher for the state constitutions than it is for the national Constitution. Between 1789 and 1991, the U.S. Constitution was amended 26 times for a rate of 0.13 (26 amendments divided by 202 years equals 0.13 amendments per year). As of 1991, the fifty state constitutions had been in effect for an average of 95 years, and had been amended a total of 5,845 times, or an average of 117 amendments per state. This produces an average amendment rate of 1.23 for the states (117 amendments per state divided by the 95 years the average state constitution had been in effect). The state rate of amendment (1.23) is thus about 9.5 times the national rate (0.13).

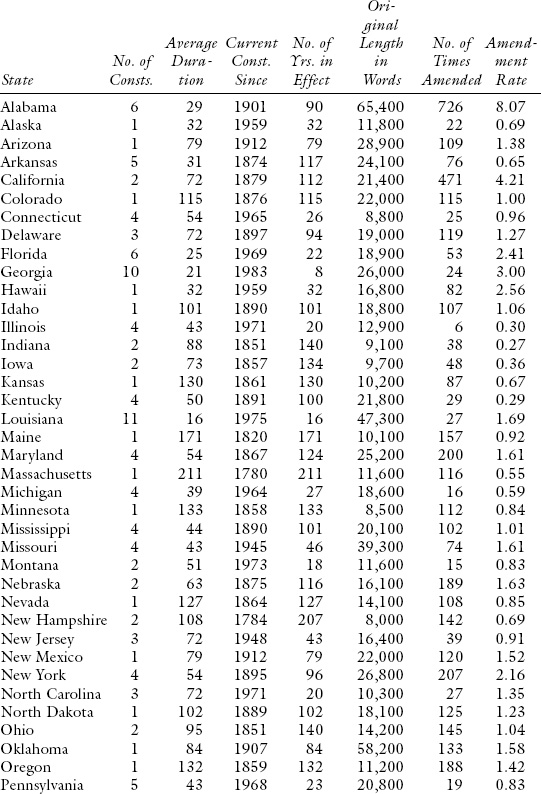

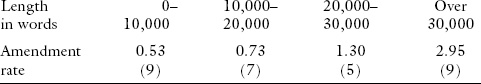

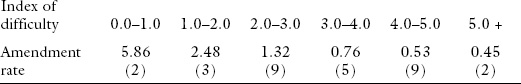

The data from Table 1 allow us to begin our analysis of the propositions developed earlier. Proposition 1 hypothesized a positive relationship between the length of a constitution and its amendment rate. The longer a constitution is when it is adopted, the higher its amendment rate should be. Table 2 summarizes the findings, which strongly support Proposition 1. Furthermore, the relationship holds whether we use the original or the current length, which includes the results of the amendments.

The average length of state constitutions increases from about 18,300 words as originally written to about 28,300 as amended by 1991. Not only is Proposition 1 supported, but there is good reason, when these propositions are being tested with foreign national constitutions, for using either the original length or the amended length. The relationship between size and amendment rate is the strongest and most consistent one found in the analysis of state data.

TABLE 1

Basic Data on American Constitutions, 1991

Source: Data on the number of constitutions, the year the current constitution went into effect, and the number of times the constitution has been amended are taken from H. W. Stanley and R. G. Niemi, Vital Statistics on American Politics (Washington, D.C.: C.Q. Press, 1992), pp. 13–14. All other data have been determined by the author.

TABLE 2

The Length of a U.S. State Constitution and Its Amendment Rate as of 1991

a The amendment rate using the length of the constitution when it was adopted. The number of constitutions in each category is indicated below the amendment rate in parentheses.

b The amendment rate using the length of the Constitution as of 1991, which includes all amendments. The U.S. Constitution has approximately 7,300 words when the amendments are included, as opposed to the approximately 4,300 it had originally.

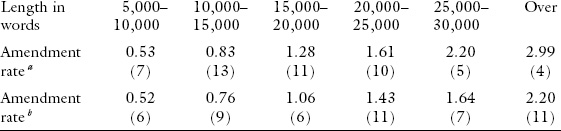

TABLE 3

State Amendments by Category, 1970–79

Source: Based on a table from Albert L. Sturm, “The Development of American State Constitutions,” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 12 (Winter 1982): 90.

State constitutions, on average, are significantly longer than the U.S. Constitution. Can we account for this difference? Proposition 3 suggests that the wider range of governmental functions at the state level results in significantly longer documents, and thus, in line with Proposition 1, produces a higher amendment rate, which makes them longer still.

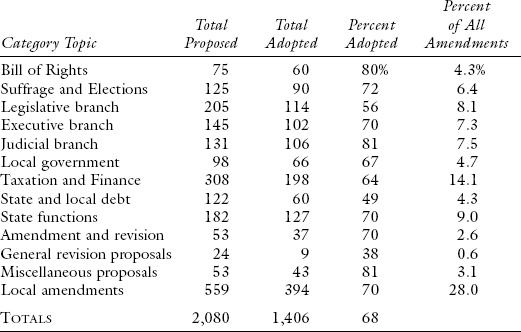

Table 3 uses data from a recent decade to show the relative importance of different amendment categories. Amendments dealing with local governmental structure (4.7 percent), local finances (an indeterminate part of 4.3 percent), or local issues (28 percent) make up at least one-third of all amendments and pertain to a topic, local government, that is excluded from national constitutional concern. Without amendments for local matters, the average state amendment rate would fall from 1.23 to about 0.8—a reduction in the ratio to around six times the national rate.

Amendments dealing with state debt and new state functions are also outside the range of national concern, and if these were excluded the state amendment rate would fall to about 0.67, which is five times the national rate.

The national Constitution deals with suffrage and election matters in two brief sentences that leave these matters to the states. However, nine of the twenty-six amendments to the U.S. Constitution deal with elections or suffrage, and therefore this category cannot be considered a special burden of the state.

Additions and changes to rights, and amendments dealing with the operation of the legislative, executive, and judicial branches, are not special burdens of state constitutions either. However, despite the Sixteenth Amendment in the U.S. Constitution, the matter of taxation and finance is to a certain extent a special state burden that adds to its amendment rate. Most of these amendments deal with what might be termed control of the cash flow. The strong inclinations at the state level to (1) limit the taxing power, (2) control the methods of raising money through other means such as bonds, and (3) prevent corruption by instituting an ever more refined system of financial checks and cross-accountability flow from a source completely missing at the national level. As a conservative estimate, we could consider about half of these amendments to be so motivated, which would reduce the state amendment rate to about 0.58, or four and a half times the national rate.

Finally, the method of amending and revising constitutions is itself the subject of amendment at the state level, though never, thus far, at the national level. If we exclude these from the count as well, we end up with an adjusted state amendment rate of about 0.54. This figure is still about four times the national amendment rate, but by eliminating the amendments that flow from concerns that are peculiar to state constitutions we now have a figure that we can compare to the national rate of 0.13 using what amounts to the same base. In other words, the difference between 0.13 and 0.54 represents what we might term the “surplus rate,” which still needs to be explained. However, an interesting question, one that seems never to be asked, is whether a state rate of amendment four times the national rate is too high, or a national amendment rate one-fourth that of the state average is too low.

The answer depends in part on your attitude toward judicial interpretation. Propositions 5 and 6 suggest that if you have reasons to prefer judicial interpretation as a means of modifying a constitution over a formal amendment process, then the amendment rate for the national document is not too low. However, if you have reasons to prefer a formal amendment process, such as an attachment to popular sovereignty, then the answer may well be that the amendment rate of the U.S. Constitution is too low and the amendment rates of the states within <#> is to be preferred.

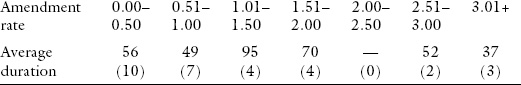

Propositions 5 and 6 assume a low rate of amendment coupled with constitutional longevity. Proposition 4, on the other hand, posits a general relationship between the rate of amendment and constitutional longevity. Table 4 provides an initial look at this relationship.

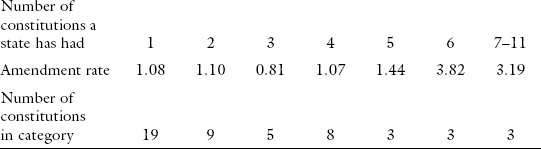

A majority of states have had only one or two constitutions in their respective histories. Three would seem to be an optimal number with respect to minimizing amendments, but even those states that have had four constitutions have an amendment rate that is below average. However, beyond four constitutions there is a marked and consistent trend toward a very high amendment rate. Why this should occur at five constitutions and not at, say, three is not obvious.

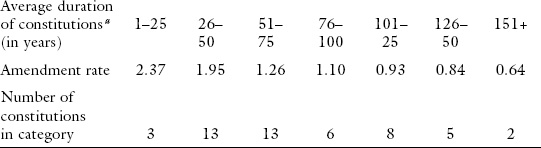

Of course, Table 4 may be measuring the difference between old and new states, since a new state cannot have been around long enough to have six, seven, or eleven constitutions. To correct for this possibility, we can divide the number of constitutions a state has had into the number of years it has been a state. The result, which we can term the rate of replacement, indicates the average duration of a state’s constitution, and is a measure of constitutional activity that controls for a state’s age. Table 5 shows the results and, together with Table 4, suggests that a high amendment rate is associated with a high replacement rate.

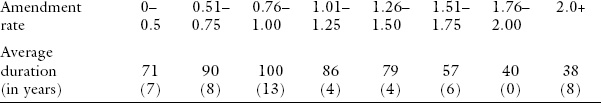

However, Proposition 4 predicts that the rate at which constitutions are replaced will increase as the amendment rate moves up or down with respect to <#>. In Tables 4 and 5 the amendment rate was the dependent variable. However, if we make it the independent variable instead, we can see if the bi-directional effect occurs, and thus directly test Proposition 4.

Table 6 shows the average duration of the state constitutions grouped according to amendment rate. The lower the average duration, the higher the replacement rate. Proposition 4 predicts that the replacement rate will be highest, and thus the average duration lowest, as the amendment rate moves above or below <#>, which is yet to be defined. Table 6 supports Proposition 4 by showing that the average duration of a state’s constitution declines as the amendment rate goes above 1.00 and as it goes below 0.76. What this means is that for American state constitutions, an amendment rate between 0.76 and 1.00 is associated with the longest-lived constitutions, and thus with the lowest rate of constitutional replacement. This range, then, will be defined as <#>.

There are thirteen constitutions with amendment rates within <#> as we have just defined it: Connecticut (0.96), Colorado (1.00), Maine (0.92), Minnesota (0.84), Montana (0.83), Nevada (0.85), New Jersey (0.91), Pennsylvania (0.83), South Dakota (0.95), Utah (0.81), Virginia (1.00), Washington (0.84), and Wisconsin (0.87). The average of these rates is 0.89, which we will use to define # within <#>.

Everything discussed to this point has dealt with characteristics of entire constitutions. Another possible source of variance, according to the literature, is the nature of the amendment process itself. We turn now to this topic as a means of testing Proposition 2, and for developing an index with which to measure the difficulty of a given amendment procedure. We will then be ready to look at the constitutions of other nations.

TABLE 4

Number of Constitutions and the Amendment Rate

TABLE 5

Average Duration of Constitutions and Amendment Rate 1776–1991

a The number of years since a state’s first constitution was adopted divided by the number of constitutions it has had since then.

TABLE 6

Amendment Rate and Average Duration of a Constitution

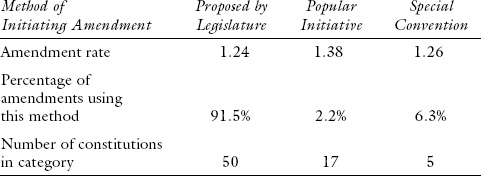

In the American states the method of ratifying an amendment can essentially be held constant: Every state but one now uses a popular referendum for approval. However, amendments may be initiated by the state’s legislature, an initiative referendum, a constitutional convention, or a commission. It is generally held that the more difficult the process of initiation, the fewer amendments proposed and thus the fewer amendments passed. Similarly, many believe that the initiative, by making the process of proposing an amendment too easy, has led to a flood of proposals that are then more readily adopted by the electorate that initiated them. Another widely held belief is that the stricter or more arduous the process a legislature must use to propose an amendment, the fewer amendments proposed.

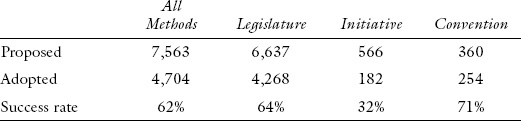

As Table 7 shows, during the period 1970–79, relatively few amendments were proposed by other than a legislature. One-third of the states use popular initiative as a method of proposing amendments, and yet even in these states the legislative method was greatly preferred. The popular initiative has received a lot of attention, especially in California, but in fact it has thus far had a minimal impact.

What has been the relative success of these competing modes of proposing constitutions? Table 8 shows that the relatively few amendments proposed through popular initiative have a success rate roughly half that of the two prominent alternatives. The popular initiative is in fact more difficult to use than legislative initiative, and it results in proposals that are less well considered. Ironically, the easier method to use, legislative proposal, tends to produce a more well-considered amendment proposal—one that is more likely to be acceptable, and thus accepted.

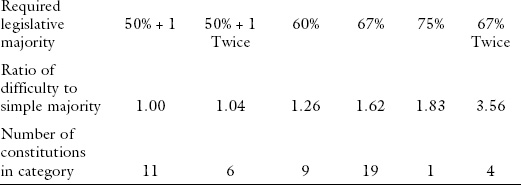

The popular initiative has not produced a flood of proposed amendments, and it is not a method with a higher rate of success. Popular initiative is a more difficult method, and has a lower success rate. But what about the varying methods for legislative initiation? States vary in how large a majority is needed in a legislature for a proposal to be put on the ballot, and some states require that the majority be sustained in two consecutive sessions. Table 9 summarizes what we find in this regard.

TABLE 7

Method of Initiation and State Amendment Rate 1970–79

Source: Based on data from Albert L. Sturm, “The Development of American State Constitutions,” Publius 12 (Winter 1982): 78–79. Total of all methods will exceed fifty since many states specify the possibility of more than one method of initiating amendments. The initiative method adds about five amendments a year nationwide beyond what we would expect using only the legislative proposal method.

TABLE 8

Success Rate of Various Methods for Proposing Amendments in the Fifty States, 1776–1979

TABLE 9

Comparative Effect of Majority Size on Amendment Rate

In this table we have normed the decline in the amendment rate produced by each type of legislative majority against that of the least difficult method. That is, since simple majority rule by the legislature results in the highest amendment rate, we ask what difference it makes to use a more difficult method for initiating amendments. The data indicate that in the American states, when the method of initiation is stiffened to require majority legislative approval twice, the amendment rate for that state’s constitution goes down by 4 percent, which is the same as making the difficulty of amendment 4 percent higher. That is indicated here by the Index of Difficulty rising to 1.04. A requirement for a three-fifths legislative majority (60 percent) reduces a state’s amendment rate by 26 percent compared to the amendment rate of states using a simple majority requirement, which is reflected here in an increase in the Index of Difficulty to 1.26.

Even though the data are drawn from the entire universe under study (American state constitutions), the number of cases (states) is too small to generate undying confidence in the results we obtain. Nevertheless, in the absence of better data, and keeping this major caveat in mind, we can reach the following conclusions from Table 9.

1. Generally speaking, the larger the legislative majority required for initiation, the fewer amendments proposed and the lower the amendment rate.

2. Requiring a legislature to pass a proposal twice does not significantly increase the difficulty of the amendment process if the decision rule is one-half plus one.

3. The most effective way to increase the difficulty of amendment at the initiation stage is to require the approval of two consecutive legislatures using a two-thirds majority each time.

One can also use the variance in the degree of difficulty between alternative legislative majorities to establish the core of an Index of Difficulty, an initial attempt at which is presented in Table 10, for any amendment process. The index identifies more than seventy possible actions that could in some combination be used to initiate and approve a constitutional amendment; together, they cover the combinations of virtually every amendment process in the world. The index scores assigned to all but a few of these more than seventy possibilities in the index are derived from data on American states. Each score is a number that represents a ratio of difficulty normed to a simple majority approval in two legislative houses, as used in Table 9.

For example, approval by a simple majority in one house is assumed to be one-half as difficult as similar approval in two houses and therefore assigned an index score one-half of 1.00, or 0.50. To illustrate another example, we know from Table 8 that amendment proposals made by popular initiative have almost exactly one-half the success rate of those initiated by the legislature in American states. Since nineteen states use a two-thirds majority, and seventeen use a simple majority, the minimum score for a popular initiative must be one-half of the weighted scores for the method used in all fifty states. This combined weighted score for legislative initiative in all fifty states turns out to be almost exactly 1.50, and thus the index score for the easiest popular initiative must be twice as difficult, or 3.00. Index scores for larger numbers of voters required for popular initiative (identified in the index as voter “petitions”) are assigned estimated increments of difficulty. As a final example, we know from state data that since 1776 64 percent of all amendment proposals made by a state legislature have been approved. We also know from state data that the approval rate is almost identical since the nearly universal adoption of popular referenda as the means of approval replaced approval by state legislatures. We can thus say that a popular referendum used as the means for approving a proposed amendment is about as difficult as having the state legislature approve it. As just noted, the average degree of difficulty for state legislative action, weighted for the relative frequency of using one type of majority versus another, is 1.50. We thus assign a weight of 1.50 to approval by popular referendum using the most usual means—one-half plus one of those voting—and add estimated increments for larger majorities.

The index score assiged to a given amendment process is generated by adding together the numbers assigned by the index to every step required by that process.

How the index works can be illustrated by using it with the amendment process described in Article V of the U.S. Constitution. There is more than one path to amendment, and each must be evaluated. A two-thirds vote by Congress, since it requires two houses to initiate the process, is worth 1.60; whereas initiation by two-thirds of the state legislatures is worth 2.25. The latter path leads to a national convention, which uses majority rule in advancing a proposal, thus adding 0.75—under the assumption that the special initiating body is elected. The first path still totals 1.60, and the other now totals 3.00. Ratification by three-fourths of the states through either their legislatures or elected conventions adds 3.50. The path beginning with Congress now totals 5.10, while the path beginning with the state legislatures and using a national convention totals 6.50. Even though the second path has never been successful, and one can see more clearly now why it hasn’t, it is still a valid option. For the total amendment process we can use the lower figure unless or until the more difficult procedure is ever used, indicate the range of difficulty by using 5.10–6.50, or average the two paths together to obtain a composite index score of 5.80. Thus far we have tended to use a weighted score that reflects the actual use of one method versus another, and since the 6.50 path has never been used, a weighted composite score would be 5.10, which is what we will use here.

TABLE 10

An Index for Estimating the Relative Difficulty of an Amendment Process

If we perform the same calculation for the American states, we find that the average index score is 2.92, with very little variance. The highest state score is 3.60 (Delaware), and twenty-six states are tied for the lowest score at 2.75. Another sixteen states have a score of 3.10. Thus, while we were able to detect variance between select subsets of states (see Table 9), in general the range of variance is modest compared with that found in the constitutions of other nations.

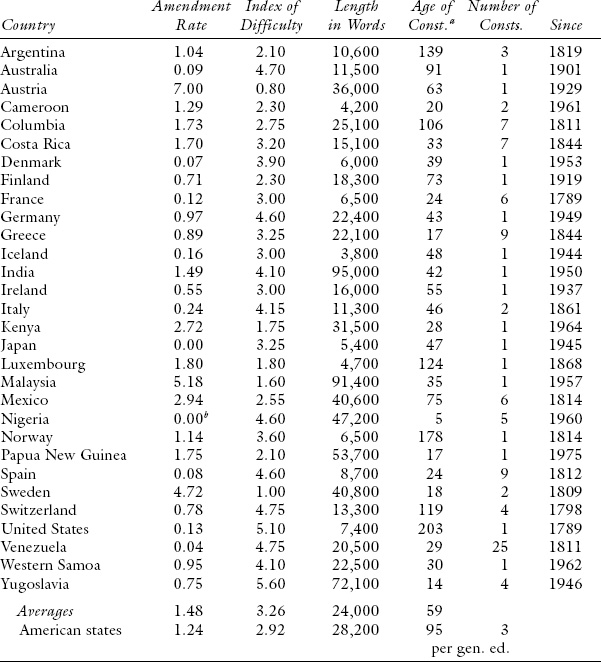

We have reached a point where we can now begin to test our propositions using data from the constitutions of other nations. Because there are fewer nations that take constitutionalism seriously than there are American states, and because data are not available for some of these nations, the total set of international constitutions that can be used to test our propositions is not very large. The results using cross-national data can thus be viewed as highly suggestive, though not empirically conclusive.

The first thing to be noticed in Table 11 is that the U.S. Constitution has the second most difficult amendment process. This implies, if Propositions 2 and 4 are correct, that the amendment rate for the U.S. Constitution is too low, because its amendment procedure is too difficult, while the average amendment rate for the U.S. state constitutions is not too high.

Table 12 shows the same basic relationship between the length of a constitution and its amendment rate that we found with the American constitutions (see Table 2).

Table 13 shows a linear relationship between the Index of Difficulty and the rate of amendment that is entirely in line with our expectations. The more difficult the amendment process, the lower the amendment rate.

Finally, the curvilinear relationship we found between the amendment rate and average duration of American state constitutions also seems to hold for national constitutions (compare Table 6 with Table 14); although now <#> seems to be somewhat higher—between 1.00 and 1.25 rather than between 0.76 and 1.00. There is a moderate range of amendment rate, which tends to be associated with constitutional longevity.

TABLE 11

Basic Data on Selected National Constitutions

a The age of a constitution in years, as of 1992.

b Data are for the most recent civilian constitution. The military constitution of 1984 revised the 1979 document by adding 206 amendments.

TABLE 12

Length of Constitution and Amendment Rate of Selected National Constitutions

TABLE 13

The Amendment Rate and the Degree of Difficulty in Amending National Constitutions

TABLE 14

The Amendment Rate and Average Duration of Selected National Constitutions

The difficulty of the amendment process and the length of a constitution are key factors affecting a constitution’s amendment rate, and thus the probability it will be replaced. A high rate of constitutional replacement is apparently associated with rates of amendment that are either too high or too low. There would seem to be a “healthy” pattern where a constitution is amended at a regular but moderate rate to keep up with change. Such a constitution will start out relatively short, and although it may over time end up having a good number of amendments, it will also be an old constitution that is still relatively short. Aside from brevity, a moderately difficult amendment process is also important. If the Index of Difficulty proves useful for measuring the difficulty of an amendment process, and thus the likely amendment rate the amendment process will produce, it should be possible to design for an inherently moderate amendment rate with more confidence.

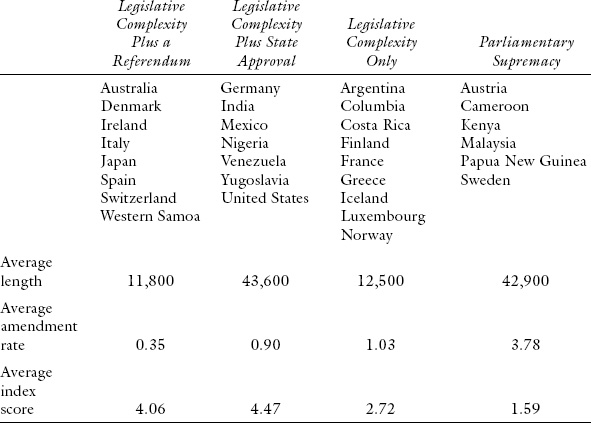

TABLE 15

National Constitutions Grouped according to Their General Amendment Strategy

To return to our initial topic, the difficulty of the amendment process may be related to a commitment to (1) popular sovereignty, (2) a deliberative process, and/or (3) the distinction between normal legislation and constitutional matters. We can examine these relationships by grouping our thirty national constitutions according to which one of four general amendment strategies is used.

Working from right to left in Table 15, the first strategy can be labeled “Parliamentary Supremacy.” This amendment strategy is consistent with the general Westminster form of government in which Parliament is the dominant player in all aspects of politics. This strategy does not utilize any of the three assumptions just listed. A second strategy is to use legislative complexity—some combination of extraordinary majority, multiple votes, intervening elections, delay, procedural checkpoints—as a means of making the amendment process more deliberative, which also draws a distinction between normal legislation and constitutional matters.

Although the Index of Difficulty rises, on average, about 75 percent as a result of this complexity, and the amendment rate falls almost 75 percent, the process is still dominated by the legislature such that we cannot say popular sovereignty is reflected institutionally.

The third strategy adds to legislative complexity the basic requirement that some majority of constituent governments also approve the amendment. This strategy thereby uses an even more complex decision-making process, which emphasizes the deliberative process and the distinction between constitutional and normal legislative matters much more than does the Legislative Complexity strategy. In addition, there is implicit an assumption of popular sovereignty, although the people are treated as grouped into substates with these state governments as a stand-in for the people. This strategy seems to reflect a rather weak commitment to popular sovereignty. However, federal systems usually need to combine a commitment to popular sovereignty with one to a highly deliberative process that protects minorities within the population, and ratification by constituent governments serves both ends. This dual need is exemplified in the Swiss amendment process, which requires ratification by both a majority of its states and a majority in a referendum. Australia, another federal system, requires a referendum that produces a majority of votes in a majority of the states. Federal systems that use ratification by constituent governments for the amendment process are committed to popular sovereignty, but their federal structure requires them to both express popular will through state mediation and provide the extra dose of procedural complexity that federal systems almost by definition require—or else they would not be federal systems to begin with. It is perhaps most correct to say that the State Approval strategy of constitutional amendment institutionally reflects an indirect popular sovereignty rather than a weak one. In any case, the State Approval strategy has an average Index of Difficulty score that is 65 percent higher than that for the Legislative Complexity strategy, and an amendment rate that is about 15 percent lower.

The fourth strategy is to add a referendum to the approval of constituent states, or in place of such state approval. This, the most difficult amendment ratification strategy, institutionalizes the most direct form of popular sovereignty, and also emphasizes the deliberative process and the distinction between constitutional and normal legislative matters. The Index of Difficulty score falls off slightly, about 10 percent, while the amendment rate falls off another 60 percent.

Table 15 also shows that countries that use a referendum form of amendment, as well as those that use solely a complex legislative form, have, on average, much shorter constitutions. These are framework constitutions that define the basic institutions and the decision-making process that connects the institutions. Except for that of the United States, and that of Germany, the nations in the other two categories use a code-of-law form of constitution, which contains many details about preferred policy outcomes and places in their documents what amounts to a basic code of law. These constitutions tend naturally to be much longer. A code-of-law form of constitution implies a reduced distinction between normal legislation and constitutional matters, as what in other systems would be “normal legislation” is put into the document. We can conclude that in general the State Approval strategy is aimed less at enhancing this distinction via a more difficult amendment process than it is in enhancing the deliberative process to protect minorities. Again, the U.S. document seems to be an exception in the State Approval category.

A number of interesting inferences can be based on Table 15. First, a short frame-of-government document using legislative complexity, without assuming popular sovereignty, can achieve about the same rate of amendment as a document based upon popular sovereignty that uses a much more difficult process but has the greater length of a code form. One can relax the level of difficulty and greatly reduce the rate of amendment simply by shortening the length of the constitution.

Second, the U.S. Constitution is unusually, and probably excessively, difficult to amend. The United States should move either to the strategy of using a referendum, in which case its amendment rate may well triple, or else reduce the number of states required for amendment ratification to two-thirds (from three-fourths), which would also roughly triple the amendment rate.

Third, we have already determined that the amendment rate is highly correlated with the degree of difficulty. We can now see that different amendment strategies, which reflect different combinations of assumptions about constitutionalism, have definite levels of difficulty associated with them. That is, institutions have clear, and in this case predictable, consequences for the political process.

Finally, both the length of a constitution and the difficulty of amendment may be related to the relative presence of an attitude that views the constitution as a higher law rather than as a receptacle for normal legislation. Certainly it seems to be the case that a low amendment rate can either reflect a reliance upon judicial or legislative revision, or else encourage such reliance in the face of needed change. It is not out of the question that the inordinate difficulties facing those who wish to amend the U.S. Constitution led to an unusually (and some would undoubtedly say “inordinately”) heavy reliance on innovative judicial interpretation.

The theory of constitutional amendment advanced in this essay has posited a connection between the four methods of constitutional alteration. Propositions 1 through 4 developed the concept of amendment rate in such a way that we were able to show an empirical relationship between the formal amendment of a constitution and its complete replacement. Propositions 5 through 9 used amendment rate to relate these two methods of alteration to the other two—judicial and legislative revision. We have now reached a point where we can systematically include these last two methods in the overall theory. Toward that end it is worth considering briefly Propositions 5 through 9 in the light of our findings on the amendment process in national constitutions.

PROPOSITION 5: A low amendment rate, associated with a long average constitutional duration, strongly implies the use of some alternative means of revision to supplement the formal amendment process.

The countries that have an amendment rate below <#> (defined as 1.00–1.50 for national constitutions), and also have a constitution older than the international average of fifty-nine years (with no interludes of military government) include Australia, Finland, Norway, Switzerland, and the United States.11 The proposition implies that these countries either have found an alternative means, such as judicial revision in the United States, or that they are under strong pressure to find another means.12

PROPOSITION 6: In the absence of a high rate of constitutional replacement, the lower the rate of formal amendment, the more likely the process of revision is dominated by a judicial body.

In the absence of further research, we have only indirect evidence for this proposition. Table 15 shows that the lower the rate of amendment, the further we get from legislative dominance. Executive revision is not a part of normal constitutional theory, so we are left with the judiciary.

PROPOSITION 7: The higher the formal amendment rate, (a) the less likely the constitution is being viewed as a higher law; (b) the less likely a distinction is being drawn between constitutional matters and normal legislation; (c) the more likely the constitution is being viewed as a code; and (d) the more likely the formal amendment process is dominated by the legislature.

Our discussion of Table 15 has supported all parts of this proposition, although only parts (b) and (d) have direct empirical support.

PROPOSITION 8: The more important the role of the judiciary in constitutional revision, the less likely the judiciary is to use the theories of “strict construction.”

In the absence of further research, Proposition 8 is a prediction to be tested. To aid that research, the next section will develop a clearer definition of “strict construction.”

PROPOSITION 9: Reasonable rates of formal amendment and replacement tend to be associated with a belief in popular sovereignty.

We now have enough evidence to reject this proposition in its strict sense. The pattern of amendment rates for national constitutions suggests the range of 1.00–1.50 for <#>, our “reasonable” range. The constitutions in the Parliamentary Sovereignty group are much higher than this range (one standard deviation from the mean of this group runs from 1.75 to 5.18), and the Referendum group is too low (0.08–0.78). The constitutions with an amendment rate within <#> are evenly divided between the State Approval (0.75–1.49) and Complex Legislative (0.89–1.80) groups, which means that about half use an institutionally indirect version of popular sovereignty, and half use institutions that imply legislative rather than popular sovereignty. Even if we relax the definition of <#> by 0.25 in either direction, we take in as many additional constitutions from each category. Proposition 9 is rejected, which implies that the assumption of popular sovereignty is not necessary for designing a useful, effective amendment process.

In our effort to develop a theory of constitutional amendment, Propositions 5 through 8 together indicate the need to develop a systematic overview of the operational attitudes toward a constitution if we are to explain the relationship between the four means of constitutional change. The relative presence of these modes of thought is the last major link in our theory of amendment.

Those who interpret a constitution are said to put a construction on the words, and thus judicial interpretation is often construed by the legal community as “constitutional construction.” Since judicial interpretation and legislative revision are prominent alternatives to the formal amendment process, it will be useful to lay out the major contending modes of constitutional construction that appear in various constitutional systems. We are interested in the extent to which a mode of constitutional construction leaves room for a formal amendment process.

What follows is a description of modes of construction as they have been abstracted from Chester James Antieu’s characterization of the answers given in various countries to the question of how they should interpret their respective constitutions.13 This list cannot be found in Antieu’s work, since he blithely mixes the different theories together. However, a careful reading allows us to unravel and describe a number of distinct positions. These theories of constitutional construction are purified in the sense that they will be distinguished from one another as much as possible. However, like Antieu, judges are likely to blend or mix principles from two or more without realizing the logical contradictions into which they have wandered. The following list, while logically defensible, is intended primarily as a heuristic device for understanding some of the possible theoretical relationships between approaches to constitutional construction and the formal amendment process.

Emphasis is placed on the intent of those who wrote the constitution—signified by careful attention to the historical records pertaining to the writing and adoption of the document as the basis for interpretation. Words are to be read as much as possible with the meaning they had at the time of the constitution’s writing and adoption. The constitution tends to be interpreted as a higher law that negates any legislation or judicial interpretation that is inconsistent with original intent. Put another way, a constitutional provision should not be interpreted in such a way as to defeat the evident purpose for which the framers wrote it. Constitutional content may be altered only through formal amendment processes that recur to a process of constitutional legitimation equivalent to that used to ratify original intent. One would expect the formal amendment rate to be high in a political system where this mode of construction is used.

Emphasis is placed on the natural and currently accepted meaning of words as found in a standard dictionary; attention is paid to the logic implied by a strict adherence to the rules of grammar; and different sections of the constitution are read together, although the constitution is not usually construed as a coherent, theoretical whole. Little if any attention is paid to original intent, or to the possible impact of one reading versus another. Indeed, it is this mode of construction that leads some courts to reach decisions that seem pedantic and contrary to common sense—such as reversing a case on the basis of a technicality that seems to be required by constitutional language. If the meaning of a constitutional passage has been altered over time by a shift in ordinary language, this is considered a valid alteration, and if such a new meaning is not acceptable, the formal amending process must be used to undo the alteration caused by the shift in the ordinary use of the language. Since changes in the use of language can be considered random in their impact with respect to the need for constitutional change, and since such a mode of constitutional construction would seem to preclude much judicial interpretation, the rate of formal amendment for a political system using this mode of construction would probably be quite high.

Emphasis is placed on the range of meaning that can be sustained by a reading of a constitutional provision using judicial precedent as determinative. Rather than seeing any provision as having a singular, exclusive, or “single-peaked” meaning, each provision is viewed as allowing a range of possible behavior that falls within the limits defined by the statement. The range of meaning, and thus the allowable limits upon the behavior it defines, is summarized in the set of legal precedents brought to bear. Thus, the meaning of a provision is subject to expansion or contraction depending upon the set of precedents deemed relevant. Constitutional purpose is contained in these precedents rather than in the “mischief” that this provision was designed to remedy. There is less room for a supreme court to maneuver with this mode of construction than with the teleological mode, although they are somewhat related, since over time judicial precedent will tend to define what looks functionally equivalent to basic principles. As with the teleological mode, pressures for formal amendment will not be strong, since adjustments in constitutional meaning can be gradually updated through evolving precedent to meet changing circumstances. Since there is less room for a court to maneuver than in the teleological mode, the rate of formal amendment will tend to be somewhat higher than in that mode.

Emphasis is placed on construing every constitutional provision in conformity with the basic principles or fundamental purposes contained in the basic law. Rather than viewing a constitutional provision in isolation, its meaning is viewed in the context of the entire document, which is viewed as a theoretically coherent whole and as evolving in its implications. Thus, there is a “progressive construction” as the basic principles of a constitution are applied to new circumstances that were not foreseen by those writing the document. Careful attention is paid to basic principles that undergird and inform the entire document. Interpreters rely upon “reasonable intent,” the spirit of the law, not upon a strict rendering of the words. That is, constitutions are not to be interpreted according to the words used in particular clauses, but rather the whole constitution is to be examined in order to determine the meaning of any part. Such an approach requires relatively infrequent amendment since only shifts in the underlying, basic principles require an alteration in the constitution. Otherwise, the Supreme Court and/or legislature may engage in broad interpretation of constitutional provisions as long as such interpretations are generally seen as being in conformity with the constitution’s basic principles.

Emphasis is placed upon what is reasonable to civilized people, with members of the court standing in as the conscience of those people. Such an approach is often typified by an interest in the decisions reached by supreme courts in other countries, but this mode of construction is just as often characterized by a judicial activism that is fueled by domestically conditioned value systems. “Natural law” can have a religious basis, such as fundamentalist Christianity, Islam, or Judaism; but it can also be secularly grounded in rationalism, humanism, or social science, for example. Secular versions will tend to be more cosmopolitan and internationalist in the implications drawn from the constitution, while religious versions will tend to be more particularistic and culture-bound in constitutional construction. Since this mode of constitutional construction provides the widest leeway for judicial activism, formal constitutional amendment in political systems using this mode will tend to be very low.

Emphasis is placed on the balancing of competing values, interests, factions, classes, social needs, or institutions, with an eye on the impact upon political society. Any form of extraneous evidence may be brought to bear, especially empirical data, scholarly works, or opinions (both legal and nonlegal) bearing on the probable relative costs, benefits, and incentives of the decision on the parties involved. Typically, the court will ask if reason or fairness demands that one side prevail even though the other party also has a constitutionally sustainable case. Such construction is often invited by constitutional provisions that contain language such as “may not unduly infringe upon,” or “may, within reasonable limits.” Such a mode of construction is usually associated with a constitution that has many such vague statements. Because the judiciary is virtually invited to determine the constitution’s meaning, the rate of formal amendment for this mode of constitutional construction is quite low.

Emphasis is placed upon finding a singular, literal meaning for a constitutional provision that is congruent with the purpose of a provision in terms of what it was intended to accomplish. There is little or no attempt to determine the logical imperatives of a theory that might make sense of the entire constitution when considered as a whole with related parts. With this mode of construction the constitutional provision tends to be read as equivalent to a normal statute, and thus not as a higher law. As with a statute, constitutional provisions are interpreted in view of the purpose to be accomplished by its enactment. Even so, with the proclivity for narrow construction comes the need to frequently alter provisions that do not address or resolve new issues, and there is a tendency for the legislature to frequently amend the constitution through normal legislation. Common law countries using the Westminster model are especially prone to this mode of construction, since that model begins with an assumption of parliamentary sovereignty. There is little need for a formal amendment procedure beyond specifying the legislature’s role in constitutional revision, although some countries using the Westminster model have a separate amendment procedure anyway.

These modes of constitutional construction have been presented in a rather “pure” form. Most judicial systems are probably a blend, since adherents of two or more modes would be contending for supremacy, although this is yet to be determined empirically. In any case, these modes have been roughly rank-ordered according to their predicted rate of formal amendment—from highest to lowest. This rank ordering must still be empirically tested, as well as the modes’ relative rates of formal amendment, but for now we will predict the following ranges of formal amendment rates, using as a basis for our estimates the amendment patterns discovered earlier.

| Range | Mean | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Strict construction—historical | 1.75–2.75 | 2.25 |

| 2. Strict construction—textual | 1.50–2.50 | 2.00 |

| 3. Legalistic construction | 0.75–1.75 | 1.25 |

| 4. Teleological construction | 0.50–1.50 | 1.00 |

| 5. Judicial or natural law construction | 0.00–1.00 | 0.50 |

| 6. Political or social construction | 0.00-0.50 | 0.25 |

| 7. Statutory construction | 3.00–4.50 | 3.75 |

These overly precise predictions suggest that once we determine the theory or theories of constitutional construction in use in a given country, the pattern will be to sort into four distinguishable categories. Those countries where we find a statutory form of construction dominant on the court and among those prominent in other major political bodies will exhibit a very high rate of formal amendment. We have used here the amendment rate we determined empirically from our examination of national constitutions. The lowest rates of amendment will be associated with constitutions where judicial (natural law) or political (social) construction is used, and it will be difficult to distinguish the two in their effects.

Countries where legalistic or teleological construction predominates will have moderate amendment rates, and it will be difficult to distingish the effects of these two modes. Finally, countries where some form of strict construction is used will tend to have an amendment rate significantly higher than the legalistic-teleological combination, but recognizably lower than that associated with statutory construction. Again, it will be difficult to distinguish the effects of the different forms of strict construction.

From this abstraction of the modes of construction we can derive several more propositions to be tested later as part of a theory of amendment.

PROPOSITION 10: The stricter the mode of construction tied to the words of a constitution, the higher the rate of formal amendment, and vice versa.

This proposition is self-explanatory from the previous discussion.

PROPOSITION 11: A relatively difficult amendment process will tend to be associated with a broad theory of judicial construction, one in which the court has few if any restrictions on how it justifies its decisions, and an easy amendment process will be associated with a narrow theory of construction.

This says nothing more than that, in the face of the inevitable need to adjust to change, the more difficult the formal amendment process, the more need there is for judicial activism in this regard, and thus the more likely that broad theories of construction will be used by the constitutional court (i.e., the less it will tend toward strict construction). A relatively easy amendment process, on the other hand, will relieve these pressures, and the constitutional court is likely to use more restrictive theories of construction. If a constitution can be altered by legislative action, the court is likely to take itself completely out of the amendment process.

PROPOSITION 12: Courts will usually develop internally competing theories of construction that are contiguous.

That is, if a theory of strict construction is used, it will tend to be in conflict with another theory of strict construction rather than with a social or natural law construction. Likewise, social and natural law theories of construction will be in competition with each other rather than with theories of strict construction. We can expect a similar competition between legalistic and teleological theories of construction. The use of the statutory construction mode tends to preclude the use of any of the others.

These twelve propositions form the core of a theory of constitutional amendment that has analytic coherence, empirical import, and normative implications. We could add other propositions by formalizing some of the points that have been repeatedly made, such as: “The statutory construction mode tends to be associated with political systems based on parliamentary sovereignty”; or “The rate of amendment may be manipulated by adjusting the length of a document and the difficulty of its amending process, separately or together”; or “Frame-of-government constitutions tend, on average, to be less than one-third as long as code-of-law documents.” However, the general parameters of the theory are now clear, as is the direction for future research.

1A good deal has been written about the role of popular sovereignty in American political thought. See, for example, Edmund S. Morgan, Inventing the People: The Rise of Popular Sovereignty in England and America (New York: W. W. Norton, 1988); and Willi Paul Adams, The First American Constitutions (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980), especially chap. 6.

2Donald S. Lutz, The Origins of American Constitutionalism (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1988), especially chap. 7.

3This position is developed further in Donald S. Lutz, Popular Consent and Popular Control: Whig Political Theory in the Early State Constitutions (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1980), pp. 218–25.

4This is the interpretation argued by Adams in The First American Constitutions, p. 139. However, most political theorists probably interpret Locke as saying that the constitution may be changed when those in power have put themselves in a state of nature vis-à-vis civil society. Under this interpretation, civil society has not ended, since the social compact is still operative—i.e., the people continue to give their consent to be bound in the selection of government by the majority. Since those in government no longer follow majority will, they have implicitly withdrawn their consent and moved outside the civil society into a state of nature. This is closer to the interpretation used by Americans during the Founding era.

5While this was the first explicit amendment process in a state constitution, the first explicit use of an amendment process anywhere was in William Penn’s 1678 Frame of Government, which undoubtedly explains why the 1776 Pennsylvania Constitution was first among the postindependence state documents. See John R. Vile, The Constitutional Amending Process in American Political Thought (New York: Praeger, 1992), pp. 11–12.

6For the phrasing and theoretical importance of this assumption, I am indebted to Vincent Ostrom, The Political Theory of a Compound Republic: Designing the American Experiment.

7 On this point, see Albert L. Sturm, Thirty Years of State Constitution-Making: 1938–1968 (New York: National Municipal League, 1970), p. 18. See also Chapter 2 in this volume, by Sanford Levinson, who notes the presence of this distinction in some state constitutions in the United States and its use at least by the California Supreme Court to strike down some efforts at change by popular referendum on the grounds that they are “revisions” rather than mere “amendments.”

8Henc van Maarseveen and Ger van der Tang, Written Constitutions: A Computerized Comparative Study (Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.: Oceana Publications, 1978), p. 80.

9For an overview of the standard criticisms about the shortcomings of state constitutions in this and other respects, see Sturm, Thirty Years of State Constitution-Making, especially pp. 1–17.

10Much of the data on state constitution making has been taken from, or calculated on the basis of data in, Sturm, Thirty Years of State Constitution-Making; Albert L. Sturm, “The Development of American State Constitutions,” Publius 12 (1982): 90; H. W. Stanley and R. G. Niemi, Vital Statistics on American Politics, 3d ed. (Washington, D.C.: C.Q. Press, 1992); James Q. Dealey, Growth of American State Constitutions (New York: Da Capo Press, 1972); Walter F. Dodd, The Revision and Amendment of State Constitutions (New York: Da Capo Press, 1970); Daniel J. Elazar, American Federalism: A View from the States, 2d ed. (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1972); Fletcher M. Green, Constitutional Development in the South Atlantic States, 1776–1860 (New York: Da Capo Press, 1971); and Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, The Referendum in America (New York: Da Capo Press, 1971). Cross-national constitutional data have been taken from the constitutions themselves, and from commentary on these constitutions, found primarily in Albert P. Blaustein and Gisbert H. Flanz, Constitutions of the Countries of the World, 19 vols. (Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.: Oceana Publications, 1987 and supplements).

11Of those other constitutions with an amendment rate well below <#>, Ireland’s will reach fifty-nine years of age in 1996, Iceland’s in 2003, Japan’s in 2004, Italy’s in 2005, Germany’s in 2008, Denmark’s in 2012, and France’s in 2017, assuming none of them is replaced before then.

12It is beyond the scope of this effort to systematically test the tendency in these countries to develop an alternate means of constitutional alteration, but Australia provides an interesting example. Australia has one of the most difficult amendment processes in the world: Proposed amendments must first be passed by both houses of Parliament, or by one house twice, and then ratified, in most cases, by both a majority of voters nationwide and a majority of voters in at least four of Australia’s six states. Certain amendments, dealing with state representation in the national Parliament and the redrawing of state boundaries, require majority approval in all six states. Australians also have a High Court that resolutely refuses to become involved in innovative constitutional interpretation. The result is rather widespread dissatisfaction among Australians with their constitution, but a continuing inability to revise or replace it. See Cheryl Saunders, “Constitutional Amendment—the Australian Experience,” paper prepared for delivery at the 1992 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, September 3–6, 1992.

13Chester James Antieu, Constitutional Construction (Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.: Oceana Publications, 1982). Use was also made of Edward McWhinney, Judicial Review in the English-Speaking World (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1956).