September 19, morning

Northern approach to the battlefield

Nichols was wearied to a fright, so whupped down he nigh on lost his fear of the Good Lord. As the Georgia men marched out of the darkness into eye-cutting light, making haste just to halt and halt again, with every man sensing—just plain knowing—a fight lay up ahead, even that mortal excitement of the spirit had not been enough to master quitting flesh and punished souls. Men stumbled along, with equally tired officers coaxing them, pulling them, all but lashing them forward, and even the stalwart fell to sleeping upright at each sudden, tempting, unreasonable halt, leaning on their rifles as female leaned on male, snoring pillars of flesh, waiting to be roused, rumple-hearted, to hurry on down toward Winchester again.

The only blessed man in the entire regiment who retained his manly vigor was Elder Woodfin. The chaplain had begun the night march ranting like a prophet against drunkenness as the hardest fellows puked out the last of their rotgut, then he preached in the pauses, warming up to Deuteronomy and howling chapter 20 over and over again, challenging Georgia’s manhood to rally itself to smite Israel’s foes, who surely lurked:

“When thou goest out to battle against thine enemies, and seest horses and chariots, and a people more than thou, be not afraid of them: for the Lord thy God is with thee…”

That was heartening somewhat, although no man was pleased at the thought of “a people more than thou,” which seemed all too frequent a situation these days. As night’s black fur grayed and slant-light stung strained eyes, the chaplain proved as relentless as Jehovah, pounding the morning with iron words: “Let not your hearts faint, fear not, and do not tremble, neither be ye terrified…,” and Ive Summerlin had muttered, “I’m too dogged tired to be terrified of much.”

Instead of quickening against Ive’s near-enough blasphemy, Nichols had found himself in sour agreement.

The daylight had taken on weight, yet another burden, and the dust was a smothering curtain a man had to gasp through. In the distance, rifles crackled, still far off, the concern of other men, and only as the sun climbed Heaven’s flagpole did the cough of artillery call for broad attention.

Men griped and grumbled, heavy of eye, but their backs began to stiffen.

Couriers spurred their horses along the line of march, discourteous. As one lieutenant pounded by, brush-your-sleeve close and freely distributing horse-stink, Lem Davis, that good Christian of soft temper, remarked, “Bet that rich boy never sprouted one blister.” To which Dan Frawley, nurtured with the milk of human kindness, added kill-voiced, “Feet probably never touched the ground in his life, even shits in his stirrups.”

“And has a nigger to reach up and wipe his ass,” Tom Boyet, who never had a nigger, said.

Of greater force than any Yankee artillery, Elder Woodfin bellowed, “What man is there that is fearful and fainthearted?”

“Passel of such, I reckon,” Ive Summerlin grumped.

They were ordered off the road to clear it for guns and supply wagons, exiled like the people of Israel, into the fields and groves, the thickets and creek-cuts, hundreds of yards to the left to shield the trains against a surprise attack by the Yankees. Just made things worse, that did, with fall-down-right-here-and-go-to-sleep men required to push through briars and clumsy-climb fences, hurrying surly through foot-wetting streams that would have been dry in September, but for the mocking rain the day before, as if, unthinkable thought, the Good Lord had switched sides and joined the Yankees, a thing impossible.

“… thou shalt smite every male thereof with the edge of the sword…”

“Suppose a bayonet will have to do,” Sergeant Alderman put in, his tired voice longing to be one of them again, to be among equals as he had been before his elevation to striped sleeves.

“Or a Barlow knife,” Ive Summerlin proposed. Untangling himself from a scourge of thorns, he added, “Lord does work in mysterious ways.”

They did fierce labor, marching cross-country while struggling to remain a proper regiment, a brigade, and not a mob, all the while keeping up with the horses and vehicles rolling along the Pike, at least a quarter mile to their right now, and every man afoot hating those who rode.

The battle sounds edged closer, yet remained without form, as the earth had been in the early time of Creation, so that a veteran soldier could not tell if either side felt serious about fighting, or even where.

With a marked limp, Captain Kennedy worked back along their ranks, or what passed for ranks, and surveyed the beat-down faces before calling, “Private Nichols to flanking duty. With them four yonder. Yanks are out there somewheres, don’t get us surprised.”

The captain, a brave man, yawned.

“Yes, sir,” Nichols said, made instantly miserable by this separation from close comrades, condemned to join men from another company, good men, surely, but still …

Ive Summerlin laughed, not harshly. “That there’s what you get, Georgie-boy, for being famed as the soberest man in the regiment.”

“Here now, give over your blanket and haversack,” Lem Davis told Nichols. “You won’t want to be laden.” And Nichols, after a moment’s doubt, passed the treasures over his shoulder, relieved to be less encumbered for this duty.

Off he went across a stubble field, over earth clotted by yesterday’s rain, thrusting heavy-limbed into the near-noon, catching up to the four men moving abreast, them advancing almost languidly, weary as the ages and wary, too.

Louder and louder. Those guns. But the war was not yet upon them, nor were they in the war. On this late and lovely forenoon, when any man of sense wished to be elsewhere.

The flankers bickered about just how far out they ought to go, cutting a path diagonal from the long gray caterpillar crawling many-thousand-footed over the ups and downs of earth eternal, five carved from the multitude, just five, headed off to skunk out the Yankee army, that ungodly agglomeration of Amorites and Jebusites.

“Keep them eyes of your’n open,” the corporal in charge warned.

Words to summon demons. No sooner had the corporal spoken than a skirmish line of Yankees rose from thick, high clover and coon brush, the closest of them not ten paces off, rifles leveled.

A burly sergeant thumbed rearward and said, in a used-to-things voice, “You Johnnies just get along now, walk back thataway. And count yourselves damned lucky.”

Nichols opened his mouth to shout a warning to his kind, but a less amiable Yankee pointed his rifle at Nichols’ belly, stepping so close that his bayonet almost touched the spot where a button had gone missing.

“Shut your pie-trap, boy.”

It was all wrong, overwhelming. This wasn’t only a skirmish party of Yankees. Long blue lines emerged from a yellowing grove. More Yankees than Nichols had ever seen this close. With a grand hurrah, the Federals rushed forward, thousands of them, hounds let off the leash. Following his four fellow captives to the rear, to Yankee Hell, Nichols paused to look back, with all the confused longing of Lot’s wife, only to stand stiffened, as if some backwoods wisewoman cast a spell on him. He witnessed a thing he had never seen, had never wanted to see, as the sweeping blue tide neared his surprised brigade. He watched his gray-clad officers struggling to bring the march formation, disordered by traitor trees, into battle order. The Yankees halted midfield and gave them a volley, disintegrating the gray ranks, then rushing at the remnants like hungry dogs. Barking, too.

Mortified, Nichols watched his own brigade break and run, a thing it had never done on any field. All of them—all of those Georgians who remained upright—just ran back into the trees, pursued by Yankees.

Nichols jumped at the tap on his shoulder. Whipping about, more nerves than man, he found a bewhiskered Yankee captain, no taller than himself, staring at him in wonder, hardly a pipe-stem off and smelling, indeed, of bad tobacco. On both the captain’s flanks, a second battle line of Yankees advanced, but the captain and those soldiers nearest him paused.

The captain gestured at Nichols.

“Chonnie, your gun. Gif it me now, or be shot.”

The captain wrenched the rifle from Nichols’ grip. Bewildered, Nichols only then realized that he had held on to his weapon, at insane peril.

For all that, he rued its loss: He had fired many hundreds of balls, perhaps a thousand, from its barrel. Toward such men in blue. It was a fine piece, cared for like the prize horse of a stable.

The captain saw its quality. Turning to a soldier, he held out the rifle and said, “Jacob, hier gibt’s eine feine Waffe, schau mal. Leave yours und nimm this one.”

Turning to Nichols again, inspecting him as if weighing a purchase, the captain said, “Du armer Kerl, du stinkst zum Himmel hoch. You go back there.” He pointed eastward, toward humiliation. “No one is hurting you. Maybe you can eat.”

But as Nichols shifted to step off, the captain caught his wrist.

“To which brigade are you belonging?”

“General Gordon’s. I mean, it was his’n.”

The captain straightened as if on parade. Delighted, he cried, “Komm mal, los geht’s! Der Gordon retreats! Los geht’s, los geht’s!”

Nichols believed he had never felt a hurt as cruel as that inflicted by those words in English.

As the foreigner-Yankees rejoined the advance—hurrying overjoyed—Nichols shambled into the trees, a crushed thing, scorched with tears. The shame of being captured, taken without even putting up a fight, was a terrible wrong. But the prospect of marching off to a Yankee jail seemed worse by a measure. He felt he would rather die than rot in a prison camp.

Surely the brigade would re-form. And the other brigades were back there waiting, closer to the Pike. When the Yankees ran into all of them, those sorry blue-bellies had to come reeling back. Gordon’s old brigade could not be whipped, it could not happen. Even if General Evans had not returned to lead it this day, Colonel Atkinson was a Christian man. The men of Georgia could not falter long, they had to counterattack.…

Instead of passing meekly to their rear, he followed the Yankees.

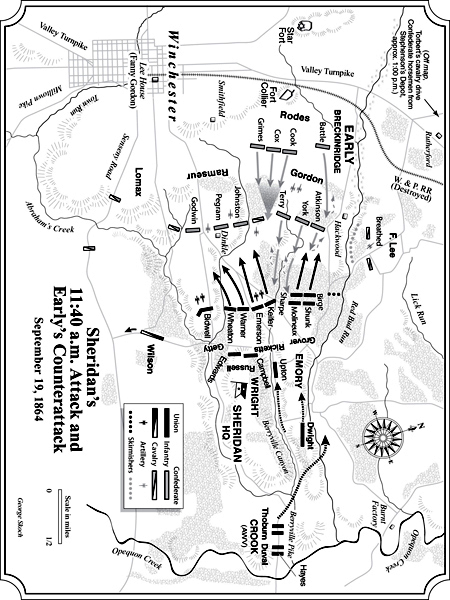

11:55 a.m.

Union center

Ricketts dared the Confederates to kill him. Galloping past knots of men left leaderless and others clutching the earth—waiting for someone, even a corporal, to take charge—he spotted Keifer near the front of his brigade, bellowing orders as round shot roared past, each projectile a miniature hurricane, accompanied by a hail of Minie balls. Behind Keifer’s mount, a crazed soldier flailed his arms as if trying to fly, splashing blood from the stumps of his wrists and keening. Keifer’s words were unintelligible, but clearly he hoped to restore his failing attack.

The brigade commander spotted Ricketts and turned his horse to meet him.

The attack in the center had faltered almost from the start. And poor Getty, on the left, was trying to advance his division over even worse ground. Only the Nineteenth Corps, on the right, seemed to have made easy progress—although Ricketts didn’t trust it. The Rebs didn’t just quit.

Keifer’s bad arm flopped in its dirtied sling. Before the colonel could speak, Ricketts said:

“I don’t give a goddamn how you do it, but get your men moving again.”

“Yes, sir. It’s that damned artillery. And there’s a gap on my right.”

“Plug it. Then take those guns.”

“Yes, sir. I’m trying.”

“Don’t try. Do it, man.”

“Yes, sir. How’s Emerson coming?”

“I’ll see to Bill Emerson. Look to your own front.”

A round shot howled by, so close they could feel its tug, almost an abrasion.

“I heard that—”

“Vredenburgh’s dead, Dillingham’s good as dead, and I need you to get the Rebs off Emerson’s boys till I get them moving again. Plain enough?”

Keifer nodded.

“Well, get on with it,” Ricketts told him.

Keifer would be all right, Ricketts decided. Just needed to be encouraged. And whipped a little.

He plunged back into the smoke, trusting to Providence that his own men wouldn’t shoot him by mistake.

With half of Vredenburgh’s neck and a shoulder torn off, Captain Janeway had taken command of the 14th New Jersey and sent a runner back for further orders—an unnerved officer’s time-honored method of skirting a decision. Ricketts rode south until he struck the Pike, then turned directly into the Rebel fires until he found the inert lines of the New Jersey men, all lying flat, as if bedded down for the night.

Janeway ran toward him. Ricketts bent from the saddle.

Unwilling to destroy the captain’s meager authority, Ricketts hissed, “Janeway, get these men moving. Now.” The junior man’s face, boyish and gilded with sweat, showed earnestness, good intent, self-doubt, and naked fear—not of dying, but of making a fateful error at his sudden assumption of command.

“Captain,” Ricketts tried again, “get your men up and continue the attack. Everyone else is making progress,” he lied. “Keifer’s almost at the Rebel guns. I need New Jersey to pull its weight today, don’t shame your state. Now … you see to your work, and I’ll get those Vermonters back there moving up on your flank.”

Janeway saluted, foolish and formal, but rushed back to his men, calling, “Colors to me! Come on, New Jersey, we’re being left behind!”

Poker was honest work compared to a battle, Ricketts decided.

He made a point of riding calmly forward, into the midst of the rising New Jersey troops, demonstrating a disdain for bullets no sane man could feel. “Come on, lads,” he shouted, forcing up a smile. “I know I can always count on the old Fourteenth.”

Given purpose and an example, men cheered him, a rare enough thing.

Ricketts made for the 10th Vermont, lied to their officers, too, and got the men going by shaming them as well. Then he praised and embarrassed the 106th New York back into action. As soon as the New Yorkers stepped off again, the Reb artillery showed it had their range, blasting great holes in their ranks, tearing men apart in a squall of blood. But the chemistry had changed and the survivors leaned into their work, quick-stepping forward, almost running, to regain their place beside their sister regiments.

His dead and wounded already crowded the fields and bands of trees, but Ricketts had his division moving again.

11:55 a.m.

Confederate center

Early screeched as he rode by Nelson’s battery.

“Pour it into ’em, give ’em hell,” the army’s commander cried. “God damn their blue-bellied souls. Just pour it into ’em.”

Ramseur’s Division was holding, desperately, but Gordon, who had promised a prompt arrival, seemed to have blundered into a scrap of his own on the far left flank. Early needed Rodes’ Division to come up—he needed it this minute—to plug the gap between Ramseur and Gordon.

It enraged him that he could not draw his army together purely by strength of will. He regretted the excursion to Martinsburg. Hell, he regretted half the things done and undone since ’61. And yes, he regretted the folly of burning Chambersburg, which he had ordered in a fit of pique, an order that fool McCausland had carried out all too well, doing his spelled-out duty for once in his life, his duty and more. Early regretted poorly chosen whores and ill-made whiskey, feuds unresolved and decent men estranged. But regret, he knew, wasn’t worth one busted rifle. Battle was of the moment, and a man in its midst did as well to celebrate past sins as to rue their doing. Conscience was a toy for men at peace.

He needed Bob Rodes. Now. And he needed Gordon to straighten out his fracas and steady the left. He needed that lazybones Fitz Lee, who had cowered too long on a sickbed, and his hardly better than worthless cavalry to do their part for once. But for the moment all he could do himself was give vent to his spite as the blue ranks rallied and pressed forward again.

“Pour it into those sonsofbitches,” he shouted in that high voice he had learned to hate himself, a voice just short of cronelike, a squeak that failed to match his splendid rage. “Kill every goddamned one of ’em.…”

12:05 p.m.

Ramseur’s Division

Stephen Dodson Ramseur watched in horror as his line broke and collapsed. Soldiers who had fought fiercely the minute before, coolly taking aim at the oncoming Yankees, began to turn from their barricades and trenches, ignoring the imprecations of their officers and fleeing, alone, then in little groups, and finally as a herd.

Delivered late and at close range, a Yankee volley scoured the line of piled-up fence rails shielding the last brave souls. Ramseur’s stoutest men turned their backs and tried to outrun an avalanche.

The Yankees cheered and surged forward.

Caught afoot, Ramseur plunged into the mob of men turned wild-eyed and frantic, men stricken by an epidemic of fear and rendered numb to the blows their officers struck with the flat of their sabers.

“For God’s sake, men! Stand and fight, stay and fight! Don’t run like women, stand!” Ramseur bullied and begged. He might have been a mockingbird, for all the good he did.

Where was that priss Gordon, where was Rodes? Dallying over breakfasts? While he held Sheridan’s army by himself?

“Stop, men! Make a stand! We’re not whipped yet.…”

“Hell we ain’t,” an insolent private snarled.

“I order every man to halt. On pain of death,” Ramseur shouted.

Not one man paused.

Ramseur picked up a discarded rifle, called, “Halt!” a last time, then started swinging the weapon by the barrel, clubbing his own men with the stock, sweeping it toward their heads as they scurried by. He hurt a few, left some bloody on the ground. All of them took it meekly, unresisting. That only made him madder.

Whether it was due to his bashing of skulls or divine intervention, a miracle gleamed: The last of his men, those who had been reluctant to withdraw, began to congeal, not quite in a line of battle, but in pockets of humanity crowding together, as if for warmth in winter. They turned their rifles on the Yankees again.

The blue advance was inexorable, though. It rolled toward them like a storm-driven tide.

But every moment, every slice off a moment, mattered terribly. The only hope of saving the rest of the army was to make the Yankees bleed for every yard.

So many of them, though. So many. Too many regimental flags to count.

His division was dissolving, from the left flank to the right. It had dissolved. And the Yankees seemed to be everywhere, with only random clots of gray-clad men and stubborn-to-the-death batteries resisting them.

A single aide remained to him, all others either slain or swept away.

Ramseur gripped the lieutenant by the forearm. “Find General Early. Tell him I can’t hold them any longer.”

12:05 p.m.

Gordon’s Division

“Georgia!” Gordon declaimed from the saddle, in a voice resonant and grand, a studied voice. “Georgia may have been surprised. Georgia may have been tricked by her low enemies. But Georgia has not been defeated. Georgia … dear Georgia … is not even dismayed. No, no! Not dismayed and barely incommoded. Georgia will rally and take her revenge on those tricksters garbed in blue.” He glowered at the disordered, panting men. “Put plain, we’re going to go back there and whip those bastards.”

The cheers from his shattered brigade were halfhearted at best, but at least they were cheers. He needed these men, his old men, needed every man. And he needed them soon. The battle growled like a monstrous bestiary as gun crews served their pieces in a fever and his other brigades, Zeb York’s Louisianans and Bill Terry’s Virginians, swung out against the snout of the Union attack, matching in ferocity, if briefly, the Federal advantage in numbers.

Gordon turned to Ed Atkinson, leading his old brigade in the absence—much lamented—of Clem Evans.

“Ed, I know these boys need time. But time is one commodity we don’t have. I need you to get them up and organized and back into the line. Won’t be long before the Yankees realize we’re snapping and snarling without a tail to wag.” He stared at the good, earnest, brave, unready man commanding his Georgians, the best choice of those available to him after the crippling bloodletting on the Monocacy. “I’m off to confer with General Rodes, see if we can’t cooperate, instead of just plugging up holes and crossing our fingers.”

Bob Rodes, bless him, had rushed up and gone straight into the line, just in time to prevent a rout, filling the gap between Gordon’s men and Ramseur’s thinned-out ranks, unleashing his leading brigade like an iron bar slammed down on a china teapot. And still it wasn’t enough. They were holding, and York and Terry had rolled back the foremost Yankees a few hundred yards—helped not a little by a battery some angel had dropped in the fields just north of a creek-cut, guns that swept the Yankees from the flank and did good business. But his gains and those of his comrades were as frail as a maiden’s wrists.

Trailed by a much-reduced staff, Gordon threaded his way between knots of stragglers and wounded men withdrawing as best they could. There seemed little danger to his person back here, with the Yankee artillery occupied in supporting their advance, but stray shots did have a way of mocking men. He rode gingerly.

He found Rodes conferring with Early, Bob nodding in his priceless way and stroking his mustaches, while Early carried on like a shopkeeper robbed and upbraiding the constable.

As Gordon approached, he heard Early say, “Close-run thing, close-run, but we can hold now. Just shore things up, we’ll hold them now, all right.”

Rodes told him, “It won’t be enough, they’ll only pound us down. Sheridan won’t quit. Grant saw to that, I reckon.”

“And you propose?” Early snapped. “What? A charge? Like damned-fool Lee at Gettysburg?” He turned, sour-faced, to Gordon. “How about you, Gordon? What do you suggest? Figure I’d better ask, since you’re bound to tell me anyway. Now that you’re done dawdling down the road.” He looked bitterly from Gordon back to Rodes and at Gordon again, shaking his head. “Jackson would have stripped both of you of your commands.”

Gordon resisted noting that Early wasn’t Jackson.

“I believe,” Gordon said in a voice artificially calm, “that General Rodes is right. If we just defend, they’re going to grind us down. Our only hope—a slim one, I grant—is to hit them right now, hard. We can do it, Bob here can do it. There’s a gap opening up, just about in the center of their attack. My bet’s on a corps boundary. Division, at least. The wing facing me’s drifting north, while the other’s hooking south. Bob’s fresh boys can run right down the middle.” He turned toward Rodes and smiled. “Or turn Cull Battle loose when he comes up.”

“I haven’t seen any gap,” Early said.

“It’s there.”

Rodes jumped in, lying his teeth off: “John’s right. I’ve seen it myself. They’ve split themselves apart, smack dab in the middle of their attack. I can ram right through.”

For all his surliness, it was clear that Early was pondering matters, giving their recommendations a fair hearing in his peculiar way. And Early, Gordon knew, was an attacker at heart, not one content to surrender the initiative.

“Damn me to bloody, blue blazes, all right, then,” Early declared. “Rodes, you see a chance, you go on in. Rip the guts out of those sonsofbitches.” He grinned, surprising both men, displaying bad teeth above his clotted beard. He canted his head northward. “My huntin’ ears tell me you’ve got yourself into another difficulty, Gordon. I’m hearing Yankee hurrahs. Best go see to it.”

And Early rode away.

The Yankee artillery fire intensified.

“Christ,” Gordon said. “Sheridan’s not playing jacks, give the little mick that. By the way, there really is a gap, Bob.”

The generals smiled at each other. “Well, if there wasn’t a gap, I suppose we’d have to make one,” Rodes allowed. “I can’t see waiting politely while Sheridan leads the dance. Shock ’em, John, it’s the only hope we’ve got.”

“Bless you, Bobby. Give those boys the devil.” He lifted his hat. “I’d better get back up there. Does sound unpleasant.”

A round of solid shot struck the earth close enough to spatter both men with dirt and bits of stone. Rodes, who wore a new-looking uniform, seemed more bothered at that than at the prospect of battle.

“Close, that one,” Gordon said.

Rodes smiled broadly, spreading his mustaches. “Close don’t count.”

No more time. Gordon pulled his horse around and teased it with the reins, no spurring required. One with its master, the great beast gathered speed.

Guns raged and the battle roared, deafening, newly alarming. Explosive rounds impacted and men screamed.

He neared a section of rifled pieces firing from a knoll, hardly a hundred yards along his way, and he realized that something was wrong. As if he smelled it well before he saw it.

The cannoneers, first of one gun, then of the next, ceased their labors and peered in his direction, openmouthed in shock. At first, Gordon thought they were startled by his appearance.

But that wasn’t it, he sensed as much in a moment. He turned to look back at whatever had caught their attention.

Through curls of smoke, he saw a dreadful thing. It was Rodes. Unmistakably. It was Bob Rodes, no longer in the saddle, but flat on the ground, as soldiers tried to control his maddened horse. The animal sprayed everyone with blood. Aides and others rushed to the fallen general. All nearby activity came to a halt.

Gordon galloped back down the slope and leapt from the saddle before his horse had stopped. Running to keep his balance, he pushed men aside then dropped to his knees beside his friend and rival.

Rodes stared heavenward, unblinking. One side of his head was a slop of jagged bone, blood, and slime. Blood drenched his chest as well.

Gordon stood up, glaring.

“All of you. Back to your business.” He firmed his spine and stiffened his jaw to master his own emotions. When he was certain that he could continue to speak without flaw or weakness, he told them, “General Rodes wouldn’t want you crying like women, he’d want you fighting. Killing goddamned Yankees. Now get to it!”

He grabbed a captain he knew to be reliable. “Ride back and find General Battle. Bring him here. I don’t care what he’s doing, you bring him here. On my order. And don’t go blathering to everybody you meet.”

“Yes, sir.”

But Rodes, before his death, had himself summoned Battle to report. Drenched with sweat and horse foaming, the brigade commander appeared barely a minute after the aide had ridden off.

“Jesus Christ,” he said when he got a look at Rodes.

Gordon turned to the dead man’s befuddled staff. “Well, don’t just let him lie there. Fetch an ambulance. Get him out of sight, take him back to Winchester.” He turned to Cullen Battle, who was a hard man. “Damned shame and worse, but there’s no time now to fuss. You’re senior brigadier, I do believe?”

Battle, still appalled, could only nod.

“Well, take command, man. By General Early’s order and on my word, you’re to take this division…” Gordon realized that he was getting ahead of himself, that he needed to explain about the gap the Yankee advance had opened. But there was no time left, every sound around them had grown ominous.

Battle rescued the situation. “And take it into that gap out there, out front of us. Yes, sir. General Early overtook me, caught me up on what’s doing. Damn Yankee fools.”

“Thrash the devil out of them, Cull. Take Sheridan’s scalp, if you can.”

“Wouldn’t say that around my Alabama boys. Might take you serious.”

They looked down at Rodes a last time as two officers and a sergeant lifted him onto a litter. Battle saluted, followed by Gordon.

John Brown Gordon took off his hat and wiped an eye.

“Sweating like a Dalton hog,” he explained. “Go kill some Yankees, Cull.”

12:05 p.m.

The fields north of Red Bud Run

Major James Breathed deemed it absurd to stand on the “dignity of an officer.” Needing to be in on the sport, he dismounted for a time and helped serve a piece, relishing the roar and recoil, the long trail of shot through the blue sky and the rising smoke, the abrupt devastation visited upon the Yankees. Fitz Lee had been right, damned right, that the high fields were a perfect artillery position. As the Yankees advanced, their right flank lay as open as a belly exposed by a clumsy surgeon’s knife. His guns had never done a better day’s service.

The Yankees appeared as foolish as they were craven, just blundering forward, one rank after another, and not one blue-belly officer in authority stopping to think, Why, my, oh my, those Rebs have guns over there, we’d best look into it. No, they just stumped forward, stalwart and stupid, and Breathed’s guns swept them away like ants.

Fitz Lee had added more horsemen from Wickham’s Brigade to defend the guns, but it seemed a waste of man-flesh and horsemeat now. The Yankees didn’t even take an interest, just let themselves be slaughtered. The ladies of Winchester might have laid out a luncheon between the caissons, for all the danger posed by Sheridan’s army. The blue-bellies didn’t even respond with artillery, let alone an infantry assault.

They deserved to lose, deserved to be killed. This wasn’t murder, just culling inferior beasts from the human herd.

Across the creek and to the right of his blue-clad, mindless targets, Breathed saw gray ranks advancing at last.

12:05 p.m.

Gordon’s front

Nichols felt caught up in one of those dreams in which things made sense and didn’t make sense at all, one of those troubling dead-of-night journeys during sleep when you watched yourself doing peculiar things, thinking all the while, That can’t be right, that can’t be right at all. He’d trailed the Yankee ranks over low hills and into swales, across shot-ripped fields and through groves sheltering skulkers, Yankees who took no interest in his wanderings, since each man’s sole concern was his own hide in his own britches.

There were wounded men, too, and dead men, some from his brigade, but none he marked from his regiment, though he didn’t look too hard, didn’t want to blunder. Most of the fallen were Yankees, though, swept by artillery fire from fields off to the north, the guns spitting flame and puffing balls of smoke, bewilderingly unmolested by the blue-bellies. Errant shells from his own kind posed more danger to him than Yankees now.

Yankee wounded drifted past him, careless of all matters beyond their pain or bewilderment. Not one bothered him or spoke a word.

Trailing the last line of Yankees at a cautious fifty yards, he crossed a stream still clear of blood, flowing quick from some spring off in a grove. He could not remember crossing the stream before, although he knew that he had been too tired to note much all the ages ago that had been that morning.

He wasn’t tired now, only gone strange, a kind of ghost, a ghost with a thumping heart. Not tired, though. Keyed up like a thoroughbred racer with peppered loins.

He stopped. Because the rear rank of Yankees stopped, just below the crest of a low hill. When they dropped to the ground, he dropped to the ground.

More shooting. Volleys. Closer. Not too close, but closer. And he heard again, at last, that kickering wail he knew, the Rebel yell.

They were coming, he’d known they’d come.

Nichols eased forward, crawling, to what he took to be a safer position, less exposed, maybe twenty yards behind the Yankees. Close enough to hear their officers shouting. It was odd to hear those words, the same words used by his officers, spoken in different accents.

A few Yankees ran past him. Nichols sprawled, playing dead. He knew that even frightened men preferred to sidestep a corpse.

More Yankees hurried rearward. Slowly, uniquely awkward, the wounded followed. Wasn’t a stampede, though. ’Least not yet. He wondered if he should have remained in that streambed a little ways back. Might pay to crawl on back there, wasn’t so far.

“They’re flanking us!” a Yankee cried. “On the left.”

And then they were off to the races, with their officers ordering their soldiers to withdraw and trying unsuccessfully to keep order.

Nichols contorted himself, throwing out an arm and a leg, imitating the dead, of which he’d seen plenty.

His heart drummed. So close. He could hear distinct cries, individual voices, wonderfully Southern. The two sides traded volleys. But the Yankees didn’t intend to hold their ground, not this ground. While Nichols prayed in silence to the Lord, repenting his sins and promising flawless behavior, he felt the approach of the retreating Yankees, telegraphed through the earth. He pressed his eyelids tight, face turned toward the earth, struggling to keep his breathing shallow, afraid a Yankee would step on his flung-out hand, or stumble over him, and cause him to reveal that he was alive.

A Yankee line paused only yards away, close enough for him to smell them and hear their leathers creak, to hear their excited gasping, as if they had to gulp all the air and leave none for their enemies.

They fired a volley. He hoped he had not flinched.

And then they were gone, withdrawing far more quickly than they had come. He waited, expecting his own kind to arrive, but more Yankees came by, last strays and skirmishers, cursing in every language in the world. They ran like rabbits, most of them.

When the footfalls stopped and only the distant cannon shook the earth, he braved a quick look around. Just as gray ranks crested the top of the little hill where the Yankees had lain and waited.

His people halted.

Glancing back toward the retreating Yankees, he saw that a few regiments withdrew slowly, in good order, defiant still, while others had all but dissolved. Just beyond the little stream, one Yankee color-bearer, admirably brave, walked calmly backward, supporting his flag with one hand and emptying his pistol with the other.

Nichols heard fateful, angry commands in Southern accents. He dropped back flat on the earth. His own side loosed a volley over his head.

Some Yankees replied, but their strength had lessened greatly. After another volley, his people advanced at a walk. Wary of nervous men, Nichols allowed the gray lines to pass over him, just as the Yankees had done.

When they had gone, he finally stood up. His impulse was to run for his own rear, to find his comrades, to be safe again, safe, if not from Yankee bullets, at least from the awful fate of a man abandoned on a battlefield, alone. But first he needed a rifle worth the carrying.

He followed the advancing ranks in gray, glancing about for a weapon that had been carried with pride, cleaned and oiled, but he didn’t get far before voices called from clots of wounded Yankees down in the swale.

“Johnny Reb, for God’s sake, give me water.” “Water, Johnny, on your mother’s love.” “Please, Johnny, water … water…”

There were so many voices, it spooked him. But no man here meant him harm.

“Tell my mother,” one voice cried, “someone tell my mother.”

“Water…”

He tugged a canteen loose from a dead Federal, rolling the man over and revealing a black hole and clotted blood where once a nose had been. Brains slipped from the Yankee’s head.

Nichols ran down to the creek. Blessedly, it was not yet tainted with blood. He filled the canteen and followed the trail of voices, returning again and again to the stream, until the water turned pink and began to redden. The men who retained some alertness beyond their pain were grateful to him. Some jabbered madly. Others wept or just stared. One gut-shot man, bubbling blood and reeking of bowel stench, drank until sated, then cried out to God.

Noble feelings had nothing to do with giving these wounded men water. Nor was it the conscious act of a Christian. Nichols had no high thoughts, none at all. He acted by rote, the way a man loaded his rifle in a battle, without thinking. The summons to action was crude, deep, and physical. He did not even pity the men to whose lips he brought a canteen. He just did a thing that needed doing, the way a man fed the chickens when it was time.

“I love you, Isabelle,” a lieutenant told him.