September 20, 1864, 3:30 p.m.

Fisher’s Hill

“Glad you’re back,” Pendleton said as Hotchkiss dismounted. “Saul needs David to strum his cartographic harp.”

The mapmaker passed his horse to the nearest orderly. The jest confounded him.

“Gordon,” Pendleton explained. “That’s what Gordon said. About you and the Old Man.”

Hotchkiss rubbed his saddle-bothered legs. “Sounds like Gordon. How’s Early?”

“About how you’d expect,” the chief of staff told him. “Blaming the sun, the moon, and the stars.” Normally fastidious, Pendleton was unkempt, dirty, and unshaven, with his collar undone and stained: He wore the look of a hard retreat, if not an outright disaster. “That’s between us, of course. Need watering, Jed?”

“Horse does, I don’t. Stopped at a farmhouse. He still on about the cavalry?”

“Hear him tell it, everything was their fault.”

“How’s Fitz Lee? Bad as the rumors?”

“Hit twice, maybe three times. Surgeons won’t give out a firm opinion.” Pendleton smirked. “Guess we’ve both seen enough of men protecting reputations they haven’t got.”

“Lee’s tough, he might pull through. Despite the surgeons.”

Around them, weary men purged old entrenchments of sediment. The weather was fine, if nothing else was.

“Touch of Jackson in Fitz Lee,” Hotchkiss went on. “Not entirely likable, but nowhere a truer heart.”

“I do miss Old Jack,” Pendleton reminisced. “Still get sick to my stomach, recalling that night.…”

“Doesn’t pay to think about it.” But Hotchkiss often thought about Jackson himself, recalling the man’s indomitable will and their shared Presbyterian prayers.

“Fitz Lee did all he could,” Pendleton resumed. “The Old Man just won’t see it. Yankees must be making cavalrymen up in those mills of theirs, never saw anything like it. Our boys tried.…”

The mapmaker nodded. “I passed the ambulance train.”

“One of the ambulance trains,” Pendleton corrected him.

“And the wagon with Rodes.”

“Godwin’s dead, too. Zeb York’s hit bad, but we brought him off. Patton was dying, we had to leave him in Winchester.” Pendleton sighed. “Not our best day.”

“Other losses? The men?”

“Can’t truly say, not yet. Strays still coming in.”

“Hundreds, though?”

“Thousands.”

“Bless us.”

“And three guns. Old Man’s angrier about the guns than anything.”

“Except the cavalry?”

“Except the cavalry.”

Hotchkiss glanced westward, scanning past a roadbed to the next height where men labored. He had been gone for hardly a week, back home in Loch Willow, then on to Staunton—where the Yankees had left a partisan force of bedbugs—but something way down deep had changed in the army. There was an odor of discontent to go with the routine stench.

“How are the men taking it?”

“Shocked,” Pendleton admitted. “Oh, they’re feisty again, talkwise. Going to lick Sheridan bare-handed, come next chance. But some of them have the jumps.”

“Not used to being on the wrong side of the outcome.”

The private truth was that Hotchkiss was sick of the war. Each time he went home, he found it harder to drag himself back to the army.

Pendleton stared northward, across the trickling run to the opposite ridge. Toward the enemy. “It’s just…”

“Just?”

“The way Early blames the cavalry…”

“The men blame him?”

Pendleton nodded. “You can’t help hearing things.”

“They’ll come around,” Hotchkiss said. Hoping it was true. If he was weary of the war, he nonetheless did not want it to be lost.

Pendleton’s eyes flashed anger. “He does his best, that’s the thing they just can’t see. He does his best, then cuts the ground out from under himself. He doesn’t have one friend, he’s pushed them away.”

“He has you. And me, if I count.”

“We don’t count, that’s the gist of it. It’s the other generals. Oh, they follow his orders, more or less, and fight like riled-up wildcats. But they just don’t like him.” A frail thing this day, the chief of staff’s temper collapsed, leaving Pendleton as glum as Hotchkiss ever had seen him. Once a font of humor—even with Jackson—the younger man had been subdued by marriage and sobered by war. Even the young were old now.

“Sheridan had the numbers,” Pendleton went on in a voice that weakened from anger to resentment. “Must’ve had three times what we had in the field. If not four. Early put up the best darned fight he could, you should’ve seen him.” He stared at the stubbled earth before his toe and kicked a clod. “I just wish he’d stop blaming everybody, talking them down. Doesn’t do any good, just makes him more enemies.” He grimaced. “Lord knows, I’m loyal to the man…”

“We both are,” Hotchkiss said.

Pendleton’s eyes were haunted. “You should have heard him an hour ago. Railing about Sheridan’s incompetence, how Sheridan should’ve done this or that and how he outfoxed him by bringing off the army. Jed, we just took a licking, and a bad one. He doesn’t help his cause, going on like that.”

“He’s never been a man to help his own cause.” Hotchkiss pictured Early in his common stance, hat brim turned up and mouth turned down, stained beard and mistrustful eyes. A man who found little comfort in this world, or in thoughts of the next.

“And Breckinridge. He’s off tomorrow,” Pendleton said. “Wangled his way out, orders from Richmond. He’s taking command down in southwestern Virginia.”

“Not much of a command.”

“He doesn’t care.”

“Always was some tension. Maybe it’s better so.”

Pendleton tried to smile. “How was your leave?”

Hotchkiss clicked his tongue, a childhood habit he never had managed to break. “Reckon I had a better week than you did. Oh, fine. Got Sara and the girls provisioned for winter. Folks are worried, though. Staunton’s had as much experience with Yankees as any of the inhabitants desire.” He began to parse his words, then decided on honesty. “Sandie, they’re scared. They put up a good front, but they’re scared to death, every one of them. They reckon that, if the Yankees come back again, it’ll go a good sight worse than it did the last time.”

“Chambersburg,” Pendleton muttered.

Hotchkiss nodded. “Can’t have a conversation, without the burning of Chambersburg coming into it. They fear the torch of vengeance. And they blame Early.”

“I don’t expect word about yesterday will provide a great deal of comfort.” Pendleton struggled to shake off his cloak of gloom. “Oh, pshaw. We’ll be all right. I’m just talking tired. Lee’ll send Kershaw back, we’ll be stronger than we were at Winchester.”

Hotchkiss, in turn, looked northward. Many a mile distant, his New York birthplace still held his parents in thrall, but he had been won by the Shenandoah, this Eden. And if it was a hard-used paradise now, the end of the war would see it bloom again, of that he was certain. He knew the composition of the soil, the strata of rocks, the springs and watercourses, and he loved that earth as the Jews of old loved Israel.

“Yankees close?” he asked.

“Cavalry south of Strasburg, on the Pike. Throw a stone and hit them. And they’re all over Hupp’s Hill. Probably watching us through a spyglass.”

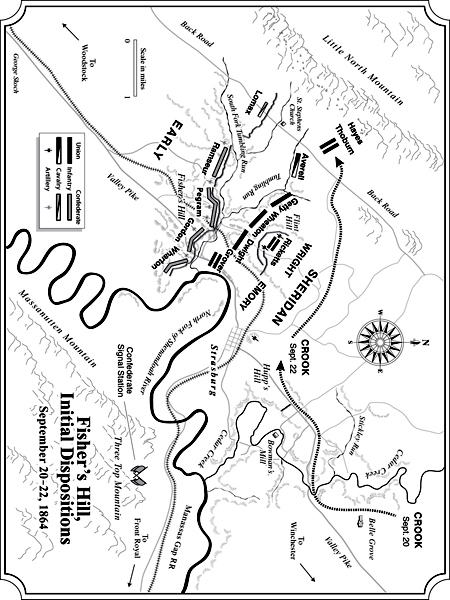

For a second time, Hotchkiss surveyed the old position, covered again with men in gray and brown: Fisher’s Hill, “the Gibraltar of the Valley.” He wasn’t a master of military art, not in its entirety. But he knew terrain. And if there was a natural fortress, a safe line of defense where a beaten army could nurse its wounds and recover, that ground was here. With the Shenandoah River a moat guarding the right flank, high bluffs rolled west for three miles before dropping down to the Back Road. Little North Mountain, rising sheer and running north to south, made a flanking movement on the left impossible. Fisher’s Hill was the one exemplary bottleneck in the entire Valley, and the Yankees had never dared to assail it, no matter their numbers. You could move against it only from the front, and attacking that way was suicide.

“Well, we’ll hold them here,” Hotchkiss said. “Buy time for General Kershaw to come back. Reckon the Old Man has a mind to see me?”

Pendleton grinned, stretching gaunt cheeks. “Well, I’m so minded. Let him holler at somebody else for a while.” The smiled curled. “You’re going to catch it for being away, you certainly picked your time.”

They walked toward a cluster of wall tents southward of the crest. Artillerymen unhitched half-lame teams and a cook got up a fire.

Pendleton said, “I had a letter from my wife. Newest Pendleton’s set to arrive any time now.” He peered across hilltops garlanded with regiments. “We’re going to be very happy.”

“Surely,” Hotchkiss said.

September 20, 7:30 p.m.

Valley Pike, north of Strasburg

“We can’t let up, can’t give them time to recover,” Sheridan said. A lantern lit the tent, turning faces orange. The gathered generals looked tired but sternly attentive. “I intend to finish this business, gentlemen.”

Horatio Wright said, “I rode up to look at the ground in front of my corps. A direct assault would be madness.”

Sheridan glared at the taller man. “Nobody said one word about a frontal assault. Now … any members of this august convocation have an idea? How to turn those bastards off that hill? I’m ready to listen.” He pivoted to face Emory. “I heard you mumbling about a move on our left.”

The Nineteenth Corps commander shook his head. “Took a good look. I’d have to cross the river twice, in full view of the Johnnies up on the bluffs. And the attacking force would lose contact with the main body, might be cut off.”

Sheridan peered down at the map on his desk. The others crowded around. As if they might summon a sudden revelation.

“They’ve got us in a fix,” Wright said.

Sheridan flared. “No. We’ve got them in a fix. And we’re going to finish what we started at Winchester.”

By preference last to speak, George Crook stood with crossed arms. “Only way to get around them, to envelop that position, is on our right.”

Wright and Emory stared at him, incredulous.

“Over that mountain?” Wright asked.

“Work along the side of it. Say halfway up. Come down in their rear.”

Wright all but sneered. “A scouting party might make it, not a corps.”

“You couldn’t keep a regiment in good order,” Emory added. “The rocks, trees, brush … an attack would fall to pieces before one shot was fired.”

Crook scratched beside his nose. “My men could do it. One division, maybe both.”

Wright gave him a killing look that said Crook was just on the brag. There was jealousy aplenty in the air over credit for Winchester.

Sheridan said, “George … that’s begging for failure.”

Crook kept his tone as calm as if counting rations. “My men have spent this war scrambling over mountains, you should see the muscles in their legs. Little North Mountain’s far from the worst climb they’ve faced.” He briefly met Wright’s eyes. “I believe such a movement offers us our best chance of success.” His attention moved on to Emory, then to Averell, the only cavalryman present. “If anyone here has a better plan, I’ll defer and shake his hand.”

Sheridan’s features mixed skepticism and hope. “You truly believe you could bring that off? And your corps wouldn’t break down into a mob? Before you went three hundred yards? You think an entire division—not to say two—could negotiate that mountain and come down on the Rebels in fighting condition?”

Crook nodded. “I can swear we’d try. Look, Phil, all of you. The only weak spot in their entire position’s on our right, out on their left. Smack at the foot of that mountain.”

Sheridan turned to Averell. “What’s Early got over there?”

“Cavalry. At least one battery of horse artillery. No sign of anything to their rear, though. Infantry are all up on that high ground.”

“For now,” Wright said.

Crook banished all emotion from his voice. “I’ve crossed Fisher’s Hill on the march, more than once. It’s a formidable position, nature’s gift to a defense. But from the river to the foot of that mountain’s nearly four miles. Takes a lot of men to man that line. And Early’s got to be stretched thin, after yesterday. No, we don’t know if we’re seeing his final dispositions, but it looks like he’s taking his risk at exactly the wrong place, figuring on the mountain to shield his flank. He should have an infantry division down there to anchor his line. But he doesn’t have that division.”

“Talked this over with your division commanders?” Sheridan asked.

“I wanted you to hear it first.”

“Bring them in, I’d like to hear their views. George, you’re playing for high stakes. I don’t intend to undercut your authority, but I need a few more opinions. From those fabled ‘mountain-creepers’ of yours.”

“I’ll have them here in an hour. If they say I’m a fool, I’ll shut my mouth.”

8:45 p.m.

Sheridan’s headquarters

Rud Hayes wished the baggage train had caught up with his division: He still wore mud stains and splashes of other men’s blood. No one in the crowded tent was dressed for a ball, but neither did they look like they’d come from a hog wallow.

“Well, Hayes?” Sheridan asked in a voice that strained at camaraderie. “Division command suit you? I hear you took those boys of yours for a swim.” Without allowing a response, he wheeled on Hayes’ companion. “Come here, Thoburn. Look at this map. You too, Hayes.”

The two colonels squeezed in beside the army commander. They towered over Sheridan.

“Look here. Little North Mountain. Know it?”

“Marched past it, sir,” Thoburn told him with a shrug.

“What about you, Hayes?”

“Fields of boulders. Steep. Tangled undergrowth.”

“Passable? I don’t want a politician’s answer now.”

“Yes, sir. It’s passable. With some difficulty.”

“By a division?”

Surprised by the question, Hayes noted that Crook’s eyes were fixed upon him. As was the attention of every man within the lantern’s cast.

“Yes.”

“Passable by an entire division? You’re confident about that, Colonel?”

“It wouldn’t go fast, but yes.” He understood exactly what was afoot now: an effort to turn the Rebs out of their position. A throw of the dice, it nonetheless made sense.

“What about two divisions?”

Hayes glanced at Crook for guidance, but the corps commander’s face was hewn of stone.

“Harder. Slower. More risk.”

“But possible?”

Hayes had taken about as much as he felt he needed to take.

“Sir, I won’t presume to speak for anyone else’s men or anyone else’s command. But my men have crawled over more boulders and worked their way through more mountainside thickets than any sensible fellow would have a mind to. My division can move along the side of that mountain or over it. With average luck, we can surprise the Johnnies, if that’s the intent. But I won’t make light of the effort.”

Sheridan canted his head toward Thoburn. “What do you think? Is Colonel Hayes here a madman?”

“Rud’s right. It can be done.”

Peeved, Wright interrupted. “I can’t believe we’re contemplating this. The Confederates would spot the movement immediately. They can see everything we do from Three Top Mountain.” He tucked in his chin, a ram about to charge. “I applaud the colonels’ enthusiasm, but I don’t believe they’d make it to Early’s rear with more than a skirmish party.”

“Well, you won’t bear the responsibility, if they fail,” Sheridan said. “I will.”

Crook stepped closer to the table. The map’s edges had curled. “Right now, they can’t see a single man in my corps. We’re still north of Cedar Creek, tucked out of sight.”

“They’ll see you when you move,” Emory countered.

Crook looked at Sheridan. “I propose that the army move in close to keep Early occupied, hold his attention through tomorrow. Demonstrations, maybe a feint or two. Steal a little ground. Make it appear as though everybody’s engaged, as though the whole army’s up and we’re positioning ourselves to hit him straight on. I’ll move my corps tomorrow night, at dark. Get close enough to the base of the mountain, then give the men a rest, but keep them hidden all through the approach march. On the mountain itself, the foliage is still so thick they won’t see us coming. And I’ll make sure they don’t hear us. We’ll go in light, knapsacks grounded, canteens and scabbards secured.” He stared down any last doubters. “We’ll hit them well before dark, day after tomorrow.”

“Give Early a full day?” Sheridan said sharply. “And most of another day?”

“We lose some time, granted. And Early keeps improving his defenses. But not on that flank. We’ll turn Fisher’s Hill into a trap. Catch him from behind in his own trenches, bury his army right there.”

Sheridan reared up, a little bull. Everyone realized that the decision had been made.

“George, you’d damned well better keep your men out of sight. And if you can hide a corps from the Rebs, God bless you.” He turned to Wright and Emory. “Push forward at first light tomorrow. Skirmish, keep the Rebs watching, parade around. Any local terrain we can use to advantage, drive the Rebs off it. But don’t become decisively engaged. Just make Early drool in his beard, thinking we might be stupid enough to hit him from the front the following day.”

He turned to Averell. “Push Lomax down the Back Road in the morning, make sure none of his scouts get near Crook’s boys.”

And to Wright: “What’s your order of march? Who’ll be closest to that mountain when you deploy?”

“Ricketts.”

“Jim needs to show his mettle. Press the Rebs hard enough to keep them fixed and expecting a frontal assault over on their left. He’ll have to chew forward a bit, accept some losses.”

Sheridan considered the men gathered in the tent, the weary men who won the day at Winchester. The air under the canvas had grown humid and ripe from sweat. And sour with new rivalries.

Sheridan slapped the flat of his hand on the map. “When Crook’s men begin rolling up Early’s flank, I want everyone pressing forward, no matter how ugly it looks out there in front of you. Don’t let Early shift troops to shore up that flank. Pound them. And when they break, by God, this time we’ll finish them.”

September 21, 5:00 p.m.

Gordon’s Division

Gordon walked among his men on the high ground of Fisher’s Hill, wielding a jovial mien to meet their complaints. The weather was a mercy, dry and clear, and Sheridan had been merciful as well. Beyond seizing the gun pits on Flint Hill, in between the armies, the Yankees hadn’t made too much of a fuss. The soldiers around him had been spared this day.

“’Tain’t fair, General,” a thick-bearded corporal declared.

Per custom, Gordon played along. “And what, on this delectable afternoon, could trouble so fine a soldier?”

“We’re way up here, up on this hill,” the man explained.

Gordon reset the hat that Breckinridge had left him as a parting gift. It didn’t fit nearly so well as the one he’d lost two days before.

“Well, it does seem to me,” Gordon told his interlocutor, “that ‘up here’ isn’t so bad a place to be. I’d rather be up here, with the Yankees down there, than the reverse.”

“’Tain’t the Yankees,” the fellow said. His comrades had gathered around, sensing another of Gordon’s famed exchanges. “No, General, it’s that we’re up here and those boys General Ramseur done took up are way over there, with another division between us.”

“And why is ‘over there’ better than here? I confess my mystification.”

“Well, lookee. They’re right there above the cavalry, ’twixt them and that mountain. One of those nags drops down stone dead, all those boys have to do is trot on down and carve themselves out some dinner. All we get is crackers.”

“Cavalry might have a say in the divvying up,” Gordon observed. “Anyway, none of those nags have enough meat left on their bones to feed two Georgians.” He smiled. Generously. A smile was about all he had left with which to be generous. “I reckon the point is that you boys are getting rambunctious for a good dinner.…”

“That’s about right, sir.”

An invisible hook raised a corner of Gordon’s mouth. “Wouldn’t mind a proper feed myself. Won’t be tonight, though.” His smile tightened. “Unless some noble Achilles were to intrude on General Sheridan’s repast.…”

“That’s the doggone thing, right there,” a soldier declared. “Worst thing about losing a battle, you don’t get to feed off the Yankees. Had my eye on a fellow looked like a great, big Dutchman, figured him for a haversack full of sausages. Then, ’fore you knowed it, I was headed the wrong way.”

“And here we are,” Gordon said. “I feel abused myself, boys. I’ve long been partial to letting our Northern confrères supplement our diet, only seems proper.” He remembered, fondly, bags of coffee beans captured in the Wilderness. “We’ll put things right, though. We’re just taking a breathing spell.”

“That’s a fact,” the first speaker said, contented to have fed on Gordon’s attention, if not on salt pork.

“Boys, you’ll have to excuse me. I daresay Colonel Pendleton’s got his eye on me from yonder. I must not be truant.”

“You tell General Early how to fix things,” a bold man said. “He’ll listen to you, General.”

“As Agamemnon paid heed to Ulysses,” Gordon said wryly, his private joke.

“Hope that ain’t catching,” a wag exclaimed to the common delight of the men.

Gordon gave them a soft salute, still studiedly genial, and strode off. In the distance, skirmishers crackled at each other, but the relative calmness of the day made Gordon wonder if Sheridan had been snake-bit bad enough to have grown wary. Or perhaps he was just flummoxed by Fisher’s Hill. Either way, the respite was dearly welcome. The men needed time.

Pendleton met him in midfield, just below a battery tucked behind gabions.

“Any word on Clem Evans?” Gordon asked. Before the chief of staff could speak.

The younger man shook his head.

“Well, I know he was headed for Richmond,” Gordon went on. “Could have used Clem back at Winchester, that’s the truth.” He repositioned the too-tight hat again. “Can’t accuse John Breckinridge of having a swelled head.” He removed the hat and held it in one hand. “Early calmed down?”

“Depends on when you walk in on him. Now he’s on to how Sheridan’s a coward for not attacking.”

“Take a fool to attack us here.”

“Well, that’s the point, I’d say. The general wants Sheridan to attack. So he can redeem himself. He’s convinced the Yankees will hit us tomorrow, come straight at us.”

Gordon noted a slight alteration in Pendleton’s tone, in his choice of words. The chief of staff was usually disinclined to criticize Early and eager to explain his worst behavior.

“I don’t know,” Gordon told him. “We’ve got Sheridan stuck, all right. But he’s got us stuck every bit as bad. He can’t attack, we can’t retreat. Not without risking a whipping out in the open.”

“He knows that. That’s the heart of it, I think. He feels his hands are tied, he’s not accustomed to it.”

“Well, I’m all for resting this army a few more days. Morale’s still a tad too flimsy for my comfort.”

The two strolled down past the gun muzzles and back toward the cluster of headquarters tents. “Have something for me, Sandie?” Gordon asked. “Looked as though you were coming on with a purpose.”

Gordon glimpsed reddening cheeks.

Pendleton confided, “I just needed to step away for a time. Told the general I was having a look to your front.”

“Nothing new to see. You can report that in all honesty. Any word from home?”

“Yes, sir. Thanks for the asking. Just had a letter. In the middle of all this, isn’t that some luck?”

“New addition to the family tree?”

“Not yet. Any day now.”

Gordon donned a practiced smile. “You’ll like being a father. Nothing like it.”

“We’re going to be very happy.”

A lone cannon barked on the left. Pegram’s front? Or Ramseur’s? Early had rearranged the division commands, with Ramseur taking Bob Rodes’ big division and Cull Battle sent back down to his brigade. Pegram now led Ramseur’s old division, while Wharton remained in command of the men left behind by Breckinridge. And Lomax had the cavalry on the field, an uninspiring, inevitable choice.

Gordon understood the logic, but wasn’t sure of the wisdom of the changes. When a fight was imminent, he preferred keeping officers above the men who knew them and with the men they knew. But what choice was there, after all? With Rodes gone? And Fitz Lee just hoping to live? Early was doing his best, Gordon had to grant, but something he couldn’t quite nail down left him uneasy.

Then there was Sheridan, whose tenacity at Winchester had been fearsome. Clearly, the little fellow was in Grant’s mold. It did not bode well.

“Any more word from Mrs. Gordon?” Pendleton asked, as if recalling that other men, too, had wives.

“Well on her way to Staunton, might even be there. Damn me down to the toenails, if she didn’t get away cleaner than this army. Amazing woman, God’s own blessing upon me.”

Pendleton opened his mouth to speak, but he swallowed the words.

September 21, midnight

Gordon’s position

More and more, he feared going to sleep. It wasn’t a child’s hants that troubled Nichols, nor was it the devil mind’s sinful imaginings, but the things of the day that came rushing back at night. He didn’t want to cry out in his sleep, the way Lem Davis did, waking men with his sudden shouts of “No, no!” But far too often the dead died again in his dreams, dead comrades and dead Yankees, crowding in on him. Sometimes they died exactly the same way he’d seen them perish, just doing the same thing over again. Other times their fates got twisted up, muddled and gruesome, beyond the power of any words to tell. Again and again, the dead tried to take him with them, beckoning with pale hands and horrid faces. He felt more dread, more terror, in the night than he ever had experienced in battle. In the night, in dreams, a man could not defend himself.

In the Good Book, dreams were either visions or warnings. What did his mean? Were they sent by the Lord, or by Satan?

He would have liked to talk to Elder Woodfin but was ashamed. A true man wasn’t scared of things like nightmares. All he could do was to pray for the dreams to stop.

Lying awake on pebbled ground, on a blanket worn thin as muslin, he held his eyes open, watching the stars, on guard for his mortal soul.

What if a man shut his eyes and never returned? What if he couldn’t wake up, couldn’t escape? What if death—a sinner’s death—left him eternally captive to his dreams? Nichols shuddered. The prospect seemed far worse than devils with pitchforks.

Someday, he promised himself, all this would end. He would go home and marry a woman as faithful and good as Ruth, and she would comfort him. He would close his mind against these things forever.

“Dear Jesus,” he begged, “don’t let none of my friends know I’m so afraid.”