October 17, noon

Fisher’s Hill

“Congratulations!” Clem Evans said as the farmhouse emptied. “Child’s a wonderful thing, a perfect blessing.”

“I do feel blessed,” Ramseur told him. His expression was milder than Evans ever had seen it. “More blessed than any man has a right to feel. And Grimes got his own good news right after mine.” His eyes traveled far. “Whip Phil Sheridan … maybe I can go home. See Nellie, the baby.”

“Boy or girl?”

Ramseur ran a palm over his gone-bald-too-young scalp. “Signal didn’t say. Just that everything went fine, the crisis passed.”

“Well, that’s blessing enough.” Evans paused, revisiting his own happiness. “Will say, though, a little girl’s less trouble. My boy, my Doodie now … he’s a trial to his mama, mischief he gets up to.” A proud, indulgent smile warmed his face. “Love the little devil, man can’t help himself. You’ll see.”

It was a wonderful thing, a thing worth pondering, Evans decided, an outright mercy. The way news of the birth of another man’s child could lift so many hearts amid a war. Friends and comrades did not content themselves with the standard felicities, but showed an honest pleasure, almost delight, in another man’s news—even if the event rekindled their own longing for home, for their own loved ones. Perhaps, Evans thought, it was just the affirmation of life between all the deaths, the promise that a man’s blood would go on, a swaddled, mewling hint of resurrection.

After Early abruptly ended the meeting, Evans had waited to be the last to shake Dod Ramseur’s hand, allowing his fellow generals and their attendant colonels pride of place. He reckoned that humility was as becoming in an officer as in a preacher. Rare, though.

As the last of their fellow commanders escaped the headquarters, leaving the mice and wrecked furniture to hurry back to their empty-bellied troops, the two men lingered, each unwilling to let go of the moment. Sparked with happiness, Ramseur added:

“Speaking of devils, Clem … I hear you gave the boys a blaze of a sermon, downright fiery. Glad to have our ‘fighting parson’ back.”

Evans refreshed his smile, the way a man sometimes had to in the pulpit, when worldly tremors shook the hope of Heaven. Ramseur was a good and sturdy Christian, if no Methodist, but the youthful general’s faith had a darkling tinge. Evans hoped that his Sunday sermon had, indeed, been heartening, but it hadn’t been “fiery,” not in the hellfire sense. As the war turned ever grimmer, his faith shone kindlier. Never had been a hard-gospel man, for that matter.

Evans moved the wrong way and a spear pierced his right side. Those pins. He still suffered breathtaking pains when he stirred himself heedlessly: The surgeons had not been able to extract all the fragments left by the packet of pins that got in that bullet’s way on the Monocacy. But a man could live with pain, he could learn how.

Wistfully, Evans remembered his train trip home, barely able to stand and his stitches oozing—sometimes bleeding—and there on a platform he’d spotted his wife by blessed chance as she waited to board a train headed north to find him. Their encounter amid Georgia’s suffering and confusion had been a little miracle of the Lord’s. He had hugged her tight right there, in front of all, gripping her fiercely, almost wantonly, with his wound shocking him with bolt after bolt of pain. His flesh shrieked, “Let her go!” insistent and heartless, but he would not, could not, do it, utterly unable to release her, clutching her warm and living and loved against him, and Allie clinging in return, making the pain ever worse until hot tears fled from his eyes, and as she felt the wet on her pressed-close cheek, she had said, sweetly bewildered, “Clem! You’re weeping.”

“Best be off, I reckon,” Ramseur said. “Plenty to do before morning.”

“Surely.”

Neither man moved.

“Like to hear a real plan,” Ramseur added, glancing around to be certain Early was gone. “Old Jube’s keeping things close.”

“I suspect we’ll hear this evening.”

“Doesn’t leave much time.”

“Not much.”

Both men had lost their smiles.

“I do miss Sandie Pendleton, that’s the truth,” Ramseur admitted. “Kept the old man as close to even-keeled as anyone could.”

“I’ve prayed for his soul,” Evans said.

General Gordon, on whom Evans had been waiting, broke off a discussion with Jed Hotchkiss. The Georgian left the mapmaker hunting through papers.

“Well, Dod,” Gordon said, voice rich, “you’re shining like the polished shield of Perseus, like the bright helm of Achilles.” When Gordon grinned, the left side of his mouth lagged behind the right, constricted by an old scar. His Antietam wound, Evans knew. “Fatherhood will do that to a man.”

“Feel like I could run barefoot to North Carolina,” Ramseur said, reminded that there was happiness in the world. “I want to see Nellie and the baby so bad.”

“Well, don’t run off just yet,” Gordon told him. “We’re going to need you. Way I’ve been in terrible need of Clem here, while he was home luxuriating.” He settled a hand, briefly, on Ramseur’s shoulder. “And when you do go, Dod, I suggest the train.”

“Do you have any sense of what Early’s thinking?” Ramseur asked. “He called us all in here, then told us round about nothing. Just ‘prepare to attack in the morning.’ That’s hardly…”

“Hardly like to build confidence,” Gordon completed the thought. “Fact is I don’t believe he’s made up his mind. About this attack, how to do it. He’s looking at hitting them on their right, over where the ground gentles out. But that’s too obvious, and he knows it.” He gestured toward the landscape beyond the walls. “And Fisher’s Hill doesn’t bring back the best of memories.” He turned to Evans. “Be glad you weren’t there, Clem.”

“Strength’s back up, though,” Ramseur countered. “With Kershaw back. We’ve got almost as many men as we did before Winchester.”

Gordon nodded and folded his arms, a favorite stance. “Numbers are fine, but I’m not sure about morale. These men need to win. And as for reinforcements, Kershaw’s it. No more men in Lee’s pocket, we have to get this one right. Or the Valley’s gone forever.”

Deprived of his cheer again, Ramseur stared at the floor.

Laying a hand on the younger man’s shoulder, Gordon told him, “Go on back to your men, Dod. Do what you have to do. Then think about your good news, let yourself savor it. Hotchkiss and I are going to have a look at things, see if we can’t devise some martial astonishment.” He turned. “Clem, you’re welcome to come along, I’m minded toward your company. If you feel ready to drag that carcass along.”

“Where?”

“Signal station. Up on Three Top. Tough climb, I’m told. Fair warning.”

Evans caught Gordon glancing at his side.

“Hotchkiss was up there in August,” Gordon continued, “makes it sound like Mount Olympus, only prettier. Claims a man can see the entire world.” He produced a smaller, fiercer smile. “Figure we’ll have a look at Sheridan’s bunch, see if those boys are still sitting on their backsides, gobbling salt pork.” The smile died. “Find out what’s waiting for us, if nothing else.”

October 17, noon

The War Department, Washington, D.C.

“No,” Sheridan said.

He looked in turn at the two men arrayed against him, meeting their glowers with an assurance he had not felt on his last visit to this office. Two months and a string of victories made the difference.

The room smelled of wax and cigar smoke.

“No,” he repeated. “I just don’t see it.”

First, he addressed Halleck, a bug-eyed, blustering man who had saved him from obscurity three years before, a man who’d possessed the skill to organize armies, but not the gift for leading them in battle. Now his hour was past, eclipsed by Grant.

“Such extensive fortifications would only tie down my army. And a fortress built to protect Manassas Gap and the railroad line wouldn’t even stop that horse thief Mosby. We must remain mobile, mobility’s the key.”

“Grant’s not mobile,” Halleck said. “He hasn’t moved from Petersburg since June.” Halleck was a man who could not keep spite from his voice on the best of days. And this was not his best day.

“He doesn’t have to be,” Sheridan answered. “That’s my point. Lee’s made a fortress of Petersburg and Richmond. And he’s sacrificed his freedom to maneuver. Lee’s trapped himself, now it’s only a matter of time.”

A far greater menace than Halleck, Secretary Stanton reentered the fray from behind his desk: “There can be no more advances on Washington, Sheridan. Not so much as a feint. Not a one-horse raid.” He sat back, locking his fingers together as if grinding a tiny creature between his palms. Frozen behind spectacles, Stanton’s eyes never faltered in a staring match. “That, I believe, is what General Halleck seeks to communicate, the point of his recommendations. With the election but weeks away”—he freed the invisible animal, waving it off—“I won’t have any embarrassments. Do I speak with sufficient clarity, General Sheridan?”

Gesturing toward a table covered with plans he found ridiculous, Sheridan replied, “Those fortifications couldn’t be finished before the election, anyway.”

He was instantly sorry he’d said it. The observation was so obvious, so embarrassing to the scheme’s proponents, it smacked of insolence.

“We must … we have to consider the period after the election, too,” Halleck spluttered. “The war’s not over, nothing’s guaranteed. The security of Washington…” The man wet the air when he spoke, misting the faces of anyone sitting too near.

“Of course,” Sheridan said as a gesture of appeasement, “your design is the classic solution, General Halleck, classic Vauban. No West Point man could miss it. But with the South nearing collapse … there’s a stronger case for leaving a limited maneuver force in the Valley, just enough men to keep an eye on things, while the Sixth Corps moves to reinforce Grant and bring all this to an end. We have to move against Lee with all we have. We have to move.”

“But you don’t deny the inherent merit of fortifications,” Halleck tried. “History instructs us in their value, you know.”

“Of course not. Fortresses … have their place. It’s only a matter of using our resources as effectively as possible. At this stage in the war.” To soothe his old master further, he added, without a grain of sincerity, “It’s a shame your plan, this fortified line, wasn’t put in place years ago. It would … have made a difference. Earlier.”

He glanced at Stanton and met reptile’s eyes behind glinting spectacles. Stanton understood what he had just done, of course. But the secretary of war was no longer concerned with Halleck, an ally who had failed him.

“Grant,” Stanton said, “believes you should move your army across the Blue Ridge. And take Charlottesville. Then go on to Lynchburg, close the noose around Lee.”

Sheridan saw the trap, but not an easy way out of it. Grant was his protector, the man who had forced his appointment past these two men when they questioned his ability. But Grant didn’t see the difficulties such a move would face with the Valley ruined—if they’d cut off food and fodder for the Rebels, they’d done the same to themselves, and a long supply line over the Blue Ridge or even switched to the east merely invited partisan attacks. He’d need as many men to guard his rear as he had at the front. That wasn’t the mobility he had in mind.

But he wouldn’t criticize Grant before these men. Stanton and Halleck practiced divide-and-conquer. And Sheridan had no intention of being conquered.

“General Grant sees the thing entire, of course. I defer to him,” he lied.

He had no intention of marching across the Blue Ridge in the winter, emulating Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow in reverse. Grant could be persuaded, given time. Sheridan had already determined that when the game reached its final moves, he would be fighting at Grant’s side, not licking his wounds after a march to nowhere or sitting in some useless fortress, waiting for an attack by a phantom army.

“General Halleck?” Stanton said coolly. “My apologies for keeping you from your labors. I’ll see off General Sheridan.”

Dismissed, humiliated, and, apparently, growing accustomed to such treatment, Halleck mumbled farewell.

When the door shut behind the chief of staff, Stanton permitted silence to fill the room, to gather force. Sheridan’s ears fell prey to the suddenly audible noise from the teeming avenue—a thoroughfare even busier and more prosperous than it had been mere months before. Riches bloomed from corpses, at least in the North. Willard’s Hotel, where he’d breakfasted in haste, harbored as many men of business and favor seekers as it did do-nothing officers.

The secretary of war sat unnervingly still, a judge before whom no felon would choose to stand.

Sheridan had to remind himself that he was no felon. On the contrary, he had given Stanton victories.

The secretary introduced a tiny sound, that of fingertips tapping a closed fist.

Sheridan met his stare, refusing to waver.

At last, Stanton spoke: “It’s a splendid thing, I suppose, to see oneself celebrated in all the newspapers.” He separated his hands. “No doubt, it’s a heady feeling, intoxicating.” His viper’s eyes fixed Sheridan. “Of course, you’re too sound a man to succumb to all that. You’re wise enough to know … that today’s hero often proves tomorrow’s fool.”

The slit of Stanton’s mouth shifted in what might have been a smile. “Poor George McClellan, for example. I recall how beloved the fellow was, adored by the men and women of the North. By children, too, for that matter.” He laid a white hand on his desk. “Who worships McClellan now? A handful of traitorous Copperheads, and even they have doubts.” The faint realignment of the lips recurred. “And he dreamed of becoming president? After the press had moved on to more promising men, after ridicule had begun to coil around him? Military men … lose themselves in the labyrinth of politics, a netherworld they find inscrutably foreign. McClellan never had a chance, he hadn’t the subtle mind such matters require. And now? He’s become a horse’s ass, a ruined man. The election hasn’t taken place and he’s already half-forgotten.”

This time, Stanton’s smile was unmistakable. “And what of the soldiers, I ask you? The men on whom he counted, whose hearts he believed he’d won for all eternity? Fickle as spoiled girls. Now that we’re winning the war, they’ll go for Lincoln. Little Mac never understood human nature.” The secretary tilted his head slightly to one side, just as Sheridan had seen rattlesnakes do. “He assumed that adulation doesn’t expire. But the affections of the herd are merely the froth on a pail of milk. The bubbles fade as you watch.”

Peering over his spectacles, Stanton’s eyes glowed from the shadows of his brow. “But you, Sheridan? I look at you … and I see a man of high talent, of eminent suitability for your profession. And, I hope, of commensurate sense.” The not-quite-smile flickered. “The esteem of the public can be destroyed overnight, you understand.”

Stanton sat up straight, changing his posture as he changed the subject. “You’re absolutely convinced that Early’s finished? What about that encounter a few days back?”

“Hardly more than a skirmish.”

“Our forces withdrew, though.”

“Hupp’s Hill has no value to us. Not now. Early was just trying to salvage his pride. What little remains of it.”

Stanton nodded. “I’m also told that your signalmen intercepted a curious message. To the effect that General Longstreet had arrived.”

The secretary’s knowledge startled Sheridan.

“I don’t believe it for an instant,” he told Stanton. “The Rebs would never let the cat out of the bag by waving signal flags in our faces. They’d throw away any chance they had of surprise.” He leaned toward Stanton. “And surprise would be their only chance. No, that signal was nothing but a ruse. Longstreet never came.”

“But to what purpose? This ruse?”

“Early’s afraid, that’s my guess. He’s trying to spook me, deter us from attacking him. He can’t afford another debacle.”

“He followed you down the Valley, though.”

“Matter of pride, all of it’s about their endless pride. Trying to show he’s active, doing something. He won’t last long. There’s not a crumb to eat between my army and Lexington, and I took most of his wagons. He can’t keep his men supplied right now, let alone as the weather worsens.” He met Stanton’s relentless stare again. “Early’s played out.”

“One hopes,” Stanton said. He rose. Again, he almost smiled. “My congratulations once more on your torrent of victories.” He made no move to come from behind the desk and offer a handshake. “I hope I shall never hear the usual calumnies leveled at you—journalists are unforgiving, mind you. Look at George Meade. It’s almost as if someone poisoned the press against him. Of course, you’ll always count me among your supporters, Sheridan.” He canted his head again. “But there’s only so much a single man can do.”

When Sheridan didn’t answer, Stanton added, “I believe you have a special train? Don’t let me keep you, General.”

Sheridan nodded. “I want to get back to my army.”

“You have concerns?”

“No. I’ve just never cared for the Cedar Creek line. I intend to fall back on Winchester. Better ground.” He gave Stanton hard eye for hard eye. “I was summoned to Washington before I could start my movement.”

“Ah, yes. Conflicting demands, the vicissitudes of generalship.” The secretary took up a paper from his desk, as if it suddenly needed his attention.

Sheridan saluted. Stanton chose not to notice.

His ordeal in the city he hated wasn’t over. Halleck lurked mid-hallway. He had two colonels with him, one detestably fat and the other skeletal.

“Sheridan!” the chief of staff called in a mighty whisper. “Unfinished business, if you please.”

Christ, what now? Sheridan wondered.

“These men … my engineers … they worked on the fortress plan. Splendid work, you saw the drawings yourself. I thought they might go with you to the Valley. Men of such caliber might be a help in siting your lines for the winter. You can show them the ground around Winchester yourself, en route to your army.”

When Sheridan hesitated, Halleck added almost pathetically, “It’s the least you might do.”

“Of course,” Sheridan said instantly. “They’ll be a great help.”

“Good, good. That’s all. Bonne chance. Splendid work. Proud of you, Philip. I always could spot ability, you know. You, Grant. Had to protect you both from the wrathful powers.…”

“My gratitude,” Sheridan said, “can’t be put into words.”

October 17, 3:30 p.m.

Three Top Mountain, Signal Knob

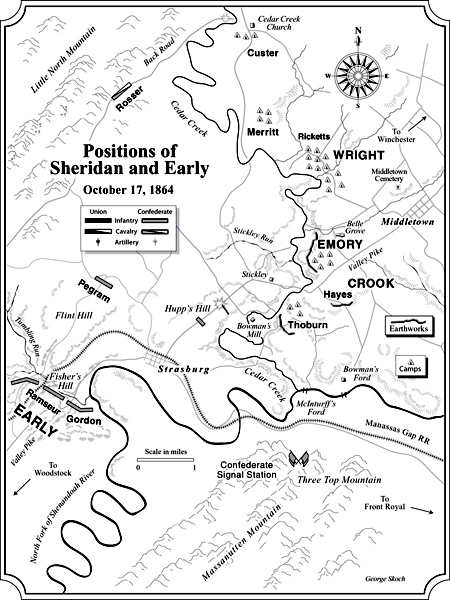

Words failed Gordon. Of all the opportunities he had witnessed—and seen squandered—nothing approached this, not even that dangling Union flank in the Wilderness.

“My, oh, my!” Clem Evans said. It was the third time in as many minutes that Evans had used the expression.

“Indeed,” Gordon commented. On a rock above them, a signalman waved his flags.

“I told you,” Hotchkiss said.

Far below, arranged like toys on a tabletop, Sheridan’s army revealed itself. The unaided eye could detect not only division encampments, but brigade allotments and regimental tent lines. With field glasses a man could spy the different uniform facings, the red of the artillery, cavalry yellow, and the pale blue that condemned a man to the infantry. Gordon could count every gun and every wagon. He could even confirm the report that the army was headquartered in the Belle Grove plantation house, busy now with the comings and goings of couriers and staff men.

Done right, a surprise attack might capture Sheridan.

“Beautiful, too,” Clem said. “Fair as the rose of Sharon.” And he was right. The Valley and its guardian mountains flamed, but with autumn reds and oranges, copper and gold, and not because of Sheridan’s pyromania. The air was bracing and clear as a maiden’s conscience, and down below—at a bruising climb’s remove—the Shenandoah gleamed as it ran northward, clinging snugly to the mountain’s base.

But Gordon had a poor eye for nature this day. His interest lay in Sheridan’s lax dispositions.

“I make it two to one against us,” Hotchkiss said.

“I like that better than three to one,” Gordon told him. Still a tad short of breath, he sighed. “Well, we know where he expects us to attack. To the extent he’s worried about an attack at all.”

“Cavalry massed on the left,” Hotchkiss agreed. “Just where General Early’s minded to go.”

“Not sure we’d even get across the creek, not over there. Not without paying a price we can’t afford.”

“I make that the Sixth Corps back toward Middletown, to the rear,” Evans put in.

“Army of the Potomac arrangement, unmistakable,” Hotchkiss said.

“Makes sense, putting them there,” Gordon told his companions. “Their best corps behind the cavalry, positioned to move to the south or west.” He passed the glasses back to Hotchkiss. “What I do find interesting is the rest of that army. Why on earth place a lone division off by itself, a mile to the south of its nearest support?”

“Looks flat from up here, I know, but they’re on high ground. Overlooking the creek bend,” Hotchkiss explained.

“I understand that,” Gordon told him. “What I don’t understand is why they’re all but abandoned out there. Just begging to be snapped up.”

“Bait?” Hotchkiss asked.

Gordon shook his head. “Can’t see how they’d spring the trap, the way the camps are disposed. And look behind them, up at the middle encampments. They’ve dug their earthworks, piled up their share of dirt.” He turned to Evans. “But what do you see? What do you see, Clem?”

“They all face south, every one of them. And the Sixth Corps hasn’t really entrenched at all.”

“Exactly. I don’t see a single stretch of fieldworks facing east. Not even southeast. Not one.”

“Problem,” Hotchkiss said, “would be getting there. Take the Front Royal road out of Strasburg to get up on that flank and they’d spot us, day or night.”

Gordon ignored the caution. “Any fords up there?”

“On the creek? Or the river?”

“The river. East of the mouth of the creek. A ford where we could get ourselves on their flank.”

“Find a farm by a river, find a ford. Wouldn’t solve the problem of getting there, though.”

“We’ll have to move along the side of the mountain. In the trees.”

Gordon saw Clem Evans lift a hand to his side, his wound. Clem had been game, but the climb, for which their riding boots had not been suited, clearly had pained him. Hellfire, it had been the Devil’s own ordeal for all of them, scrambling over rocks on all fours and forcing their way through thickets for hours, then tracing the ridgeback, thirsty and exhausted. Gordon had felt the strain of his own wounds, healed years before.

Worth it, though.

“Don’t see how,” Hotchkiss said. “River hugs the mountain tight as a corset.”

“Crook’s boys did it to us at Fisher’s Hill.”

“Smaller mountain,” Hotchkiss said. “And there wasn’t a river to be crossed twice, once when we set out, then right under Sheridan’s nose.”

Burning with visions of how a splendid battle could be won, Gordon let impatience rule his voice. “For God’s sake, Jed! You’re the one who wanted me to climb up here. You knew Early’s scheme wouldn’t work, before we saw all this. And here before us, welcome as revelation, is a potential Marathon, a Plataea. And you’re a naysayer?”

“Not a naysayer, General. Just raising a few details. Details do have a way of troubling plans, seen enough of that.” He kicked a disguise of leaves away from a rock. “I agree this has a beckoning look. I just don’t see how to get where we need to go.”

“Got to be a way,” Clem Evans said. Fire had kindled in his voice, too.

“We’ll find a way,” Gordon insisted. “Jed, we’ll find a way, you know we can. But you need to be with me, locking arms, when we put this to Early. If it’s me alone…”

Hotchkiss nodded. “I’m with you. That’s not the question.”

“What we need,” Gordon told them, “is one more day. Early’s impatient, we all know rations are short. But we need a good stretch of daylight to find a trail, a back road, anything. Find a way to pass Strasburg without being seen. Then find a ford that can cross, say, half the army.”

A fusillade of yellow leaves crackled toward them.

“I’ll pray on it,” Evans said.

October 17, 8:00 p.m.

Belle Grove plantation

“It’s the right thing to do,” Emory insisted. “Early’s no threat, he’s finished.”

Horatio Wright was doubtful. Sheridan had left him in command for the duration of his hasty excursion to Washington. The responsibility weighed more heavily than Wright had expected.

“What do you think, George?” he asked Crook.

Crook lowered a near-empty glass. Taking their ease at the day’s end, the generals were sharing a dose of whiskey. None drank heavily, and Wright only sipped his ration.

“Well,” Crook said, “I suppose I have no objection. The men are tired. Lord knows, they’ve done good service.”

“If I saw the least danger, I’d be the first to oppose it,” Emory argued. The firelight glinted orange in his red hair.

The fire was welcome: The nights were growing cold.

And yes, the men were tired.

“I’ll have the order published in the morning,” Wright told them. “Too late tonight, we’d just make a hash of things.”

“They’ll be grateful, the boys,” Emory assured him. “Standing to their weapons at two a.m. was the sensible thing a month ago. Not now, though. Campaign’s over.”

Crook had another taste of Virginia whiskey, the last wealth of the plantation’s looted cellar. “I suppose we can let the men sleep,” he said with only a slight hesitation.

October 17, 8:00 p.m.

Fisher’s Hill

“God almighty, Gordon,” Early said. “If I offered you angel’s wings, you’d cuss the feathers.”

Lit by a pair of candles, the cold room reeked. An orderly had tried to build a fire, but the chimney refused the smoke, driving out the staff. Cackling at the weakness of his subordinates, Early had declined to move his headquarters.

“I wish you could have seen it for yourself.” Speaking, Gordon studied the big, bent-over man, whose rheumatism had forbidden the climb. “If Jed and I find a route for the approach march, we could hit them just before dawn day after tomorrow, run right over them. Half their divisions aren’t in supporting distance of one another. And every last one is facing the wrong way, the way they expect us to come. They’d go down like dominoes.”

“You say.” Early spit tobacco juice into the blackened fireplace. “Haven’t seen them go down like dominoes yet.”

“Be it on my head, if this attack fails.”

“Damn you, Gordon, don’t be asinine. We get ourselves whipped, it won’t fall on your head. And you damned well know it.”

Hotchkiss stepped in. “General Early, Sheridan’s got his entire cavalry corps massed on his right. If we attack the way … the way we considered … we’d run right into them. Then the Sixth Corps would come right down on top of us.”

Slowly, bitterly, Early shook his head. “Sucking at the same teat as Gordon, are you?” He grunted. “Sandie Pendleton came back from the grave, I’d take a strap to his back for getting killed.”

“General Gordon’s asking for one day, sir. And I believe—”

“Oh, surely. ‘One day.’ And let the men eat shoe leather for dinner. Except they haven’t got any goddamned shoes.”

“It’s not as bad as that,” Gordon said.

“Not yet.” Early turned and stared at the fouled hearth. “God almighty, God almighty…” He wheeled again, ignoring Hotchkiss to shoot his scorn for all straight-backed, pomaded, woman-pleasing men in Gordon’s direction. “All right. All right, then, General Gordon. You take your day. Let it never be said I was unreasonable, let that never be said.” His spite overflowed toward Hotchkiss as well. “You take your goddamned day.”

He clomped out of his headquarters.

Gordon and Hotchkiss looked at each other.

“I’d almost describe that as pleasant,” Gordon said.

October 18, 6:30 a.m.

Fisher’s Hill

Dan Frawley fried up the rancid bacon, trying to burn the stink off it. The other men took turns tossing hardtack into the spitting grease. Nichols reckoned that none of them had figured when they signed up that the day would come when they’d be pleased to eat filth.

“Give my favorite hound for a cup of coffee,” Ive Summerlin said. “For half a cup.” In the unfixed light, he looked more like a Cherokee than ever.

“Doubt you own a hound worth a cup of coffee,” Corporal Holloway told him.

“Tell you, that’s how the Yankees been whipping us lately,” Tom Boyet offered. “They’re all rallied up on coffee. We got none.”

“Well, now,” Sergeant Alderman said, “maybe you should stroll over there for a visit, bring us some back.”

“I reckon that’s about what Old Jube’s thinking,” Dan Frawley put in. “Rations need to come from somewheres, men do have to eat. And Richmond ain’t no help.” He shuffled the bacon in the pan. It really did stink, no matter the frying inflicted. Still, it gave off enough bacon smell to madden a man.

Nichols knew he’d eat it, even if he puked it right back up.

Returned from a visit to the trees, Lem Davis said, “Surprised we haven’t gone over there already. Shows you what rumors are worth. Expected we’d take us a few Yankee haversacks, have a right full dinner.”

“I don’t mind staying put,” Ive admitted. “Not one little bit. I’m tired of getting whupped. Early’s played out.”

“Too late for Early.” Tom Boyet repeated the popular joke.

“Oh, we’ll attack,” Sergeant Alderman cautioned them all. “Only reason we’re sitting on Fisher’s Hill again. Early won’t try to defend it, not after last time. He means to attack, don’t you worry.”

“Place just makes my skin crawl,” Ive said.

“That’s your lice,” Holloway told him.

“I wager on chiggers,” Tom Boyet added. “Never had ’em worse than I did around here.”

“Hand over your plates,” Dan said. “Before this cooks to nothing.”

Careful not to nudge a comrade aside, the men accepted their portions, a mouthful apiece.

Being a town man, Tom Boyet gagged. “I can’t eat this,” he said.

But he ate it, after all.

The greased-over hardtack was fouler than the bacon, but every man chawed his to a pulp and swallowed it.

“Slick a man’s guts right through,” Lem Davis said.

“Know who I dreamed on last night?” Holloway asked. “Zib Collins. Poor Zib.”

“I dreamed about one of those big Pennsylvania gals,” Ive snapped. He and Zib had been close. “Man wouldn’t never sleep cold wrapped in that lard.”

They all had slept cold the night before. October had grown traitorous.

A leaf floated into the frying pan that Dan had laid aside.

“Quick, fry that up!” Ive told him. “Better than this ptomaine fatback, I bet.”

Dan picked the leaf from the pan and considered it. As if he really might take a bite.

Dreams. Nichols did not want to think about dreams, not about Zib and not about big, fat Dutch girls. He’d rather eat slops.

His night-world had grown violent and grisly, haunting him into the light near every day. That night, he had dreamed that his home was burning down with his ma inside. Chained by the unholy laws of sleep, he had only been able to watch, immobile and helpless. Other dreams of late had been much worse.

In his dreams the dead were not angels. And twice he had met a living woman in sleep, an unclothed woman, whose body was riddled with snakes like a cheese with worms. He dreamed of being hunted, never of hunting. Even his fondest night thoughts brought him shame.

Despite sharing blankets with Ive, he had lain awake shivering after that dream of fire. With his ma burning in a Hell made by men with torches. He did not think he’d cried out, though. That was something. In the depths of the night, sleepers shouted as they struggled with their dreams. At times, you heard whimpers in voices that surprised you. Strong by day, men shrank in the dark, and outbursts that once would’ve made for a morning of ribbing passed without comment. At dawn, men met each other’s eyes less often and hands trembled over tin plates.

Rising, Tom Boyet declared, “’Fraid I’m coming down with the trots again.”

Seemed like just about everyone had the bloody runs on and off. Nichols had been fortunate so far. He ascribed his good luck to nearly dying back in that Danville hospital: Maybe once you had it really bad, it didn’t come back. Kind of like the measles.

“Lord, for a cup of coffee,” Ive lamented. “Wouldn’t care how fast it scoured my guts.”

Elder Woodfin appeared, lugging the big Bible he favored in camp. The chaplain had grown a touch softer of late, just on the rough side of pleasant. Lem believed he was jealous of General Evans, whose sermons raised a man’s spirits instead of whipping him into a corner and keeping him there. Elder Woodfin’s homilies were ferocious, hard enough to kill any Yankee in earshot, but they weren’t always a comfort.

The chaplain squatted close enough to the fire to borrow some warmth.

“I want you boys to recall Psalm One Forty-four today. I’ll speak it out, and you’re welcome to recite with me.” He looked sternly at Nichols, demanding allegiance.

Leaves charged over the knoll.

“Blessed be the Lord my strength,” the chaplain began, “which teacheth my hands to war, and my fingers to fight…”

Nichols recited along. He had his psalms near perfect.

Fueled by the Word, Elder Woodfin’s voice gained power. “Bow thy heavens, O Lord, and come down; touch the mountains, and they shall smoke…”

Eager, Nichols plunged ahead: “Cast forth lightning, and scatter them: shoot out thine arrows, and destroy them.”

Elder Woodfin smiled with big brown teeth. Dan and Lem kept up fair, forgetting bits but then rejoining the psalm as it rolled past the “hurtful sword” and on to the plea: “Deliver me from the hand of strange children, whose mouth speaketh vanity…”

That stretch baffled Nichols every time: Weren’t children supposed to be innocent? Up to no good sometimes, even downright nasty, but why did children trouble David enough to nag his psalm? How could a warrior-king be frightened of brats? Couldn’t folks back then just take a strap to them?

Had “strange children” haunted David’s dreams?

Sun tore the haze. It would be another fine, God-given day. They would not fight.

Nichols decided to fix his mind on the last line of the psalm: “Happy is that people whose God is the Lord.”

He and his brethren were the Lord’s people, weren’t they? Surely they would be happy when God was ready.

October 18, 10:00 a.m.

Bowman’s Ford

“Yankees are like to shoot us, they catch us in these duds,” Hotchkiss said cheerily.

Pausing to scrape the soil with his hoe, Gordon grinned and told him, “Not me, Jed. Generals only get shot on the battlefield. Otherwise, we’re protected by the gods and a certain etiquette.” He cleared his throat portentously. “But a lesser fellow now, one who might not possess such august rank … were such a one caught in civilian clothes, he’d have some explaining to do. I’d put in a word for you, though.”

“I’d take that kindly.”

Shifting his stance, Gordon caught a mighty whiff of the rags he wore. Vermin were a given. Surely this day would count among the sacrifices he’d offered up to the Cause.

“Let’s go on a ways,” he told the mapmaker.

Careful not to appear in a hurry, they puttered down the harvested field, stopping now and again to prod the soil, as if its condition demanded close inspection. Glimpsed through gaps down in the trees, the sun glinted off the Shenandoah’s brown waters.

Gordon halted sharply—more abruptly than he meant to.

Feigning interest in the earth again, he asked, “See them?”

“Two. Midstream.”

“Right. Water’s at least a foot below their stirrups.”

“Farmer wasn’t lying.”

“In my experience,” Gordon said, “the sons of Ceres don’t lie. But they do prevaricate upon occasion.”

“Don’t waste soap and water on their clothes, either,” Hotchkiss noted. “Won’t mind parting with this fancy dress.”

“Go on back up. Get your uniform on and head back to camp, catch up with Ramseur. But start off slow, they’re watching us.”

“What about you?”

“Just visiting that fork over by the tree line. Tug a branch across the far trail, block it. So we don’t stray off tonight. Things do get confusing in the darkness, and I can’t risk posting a guide this close to the ford.”

“I could do it for you,” Hotchkiss told him.

“You go on. I need to have another look at things.”

“Be careful, sir.”

Gordon smiled. “I don’t intend to frequent a Yankee prison, I assure you. Fanny’s reaction, I fear, would be intemperate.” He became very much the general again. “Go on back, I’ll catch up. And if I don’t, tell Early about the trail and about this ford. Ramseur will back you now, he saw enough. Convince him, Jed.” He gave his scalp a respite from the borrowed straw hat. “We can beat Sheridan bloody, smash his army. Early just has to have faith.”

October 18, 10:15 a.m.

Bowman’s Ford

“You’re a farmer,” the cavalry corporal told his companion.

The river streamed around their horses’ legs.

“Yup,” the cavalry private agreed.

“And I’m a farmer,” the corporal said.

“Yup.”

“Ever see farmers act like those two fellers?”

“Nope.”

“Can’t figure out what they’re doing.”

“Ain’t farming.” The private spit into the stream. “And them two ain’t no farmers.”

“That’s what I been trying to tell you, Amos.”

“Didn’t need telling.”

“Captain Heurich might need telling. Rebs might be up to something.”

“No good telling that bullheaded Dutchman anything,” the private said.

“We’re down here to ‘observe.’ And I’m observing.”

“That man won’t listen, though. He don’t listen no more than a widow’s mule. Afraid to stir things up.”

“Well, I reckon we’ll report and see what happens.”

The private shook his head, watching the pair in the high field go their separate ways.

“Them two ain’t no farmers,” he repeated.

October 18, 2:00 p.m.

Near Winchester

Sheridan cursed Halleck. The two engineers imposed on him, the fat colonel and the lean, may have been wonders at planning fortifications for Halleck’s fantasies, but neither man could ride a horse worth a damn. He watched them bounce in their saddles as he and his retinue waited for them to catch up.

Wary of any men on horseback, a string of darkies paused in their search for bodies. After a month, the battlefield still held secrets. And it stank.

“You boys!” Sheridan yelled. He pointed. “Get down in that ditch there and look. That’s where soldiers would be.”

The crew had collected a wheelbarrow-load of leathers, brass, and weapons. A decayed corpse in blue rags topped the load. Sheridan wondered briefly whether the coloreds put to such labor felt all that a white man would. He decided it didn’t matter.

The fatter engineer beat the lean one to Sheridan.

“This is simply marvelous!” he declared. “Seeing the battlefield like this, right at your side, sir! It’s all so complex, the defiant geometries … so different from the newspapers.”

“I expect so,” Sheridan said through gritted teeth. “How about my winter lines? Any recommendations?”

Joining them, the lean colonel struggled to master his horse. He had no idea how to manage the reins except by yanking them. Sheridan decided not to offer advice.

“Oh, we’ll have to consult the maps for that. Make calculations.”

“You could’ve consulted maps in Washington.”

“General Halleck thought—”

“I know what General Halleck thought.” Sheridan cut him off.

Sweating grandly, the portly colonel said, “These manly pursuits do tire one, do they not, sir? After a time, the eye doesn’t see so acutely.…”

You’ll see your dinner sharp enough, Sheridan figured. Recalling the old debt he owed Henry Halleck, though, he refrained from calling the engineers “worthless bastards.”

“You’ve got my attention,” Sheridan snapped. “I suggest you two make use of it. Tired or not. I can’t spare any more time after today, there’s an army to lead.”

Without further comment, he spurred Rienzi off across the fields, letting the others follow as best they could. The previous afternoon had been squandered on a slow ride from Martinsburg as the two engineers fought to stay in their saddles and pestered him with questions. Now this precious day had been wasted, too: By the time all this nonsense was done, it would be too late to ride down to Belle Grove and rejoin the army.

First thing after breakfast, though, he intended to be in the saddle.

October 18, 2:00 p.m.

Fisher’s Hill

“No time to waste,” Early told the assembled generals. “You’ve got the details, so let’s review this quick and get the men ready.” He glanced toward Gordon with less than his normal distaste. “Gordon commands the right wing. Until we all join back up. Right wing consists of Ramseur’s Division and Pegram’s, along with Gordon’s mongrels under Evans.” He grimaced, unable to help himself. “For this goddamned plan to work, Gordon has to move half this army across the river at dark and pass the woods Indian file. Then cross again east of Sheridan before dawn. Tall order. But I expect everybody to make this work.” He looked around the room and repeated, “Everybody.”

He curled toward Kershaw and Wharton, the two division commanders he’d oversee personally. “Kershaw, you’re going to sweep right over that division they got dangling, catch ’em snoring and farting. Keep the rest of the Federals looking south. While Gordon comes down on their heads like bats in the shitter.”

He grunted, clearing his throat of phlegm and grudges. “On Kershaw’s left, Wharton advances along the Valley Pike, followed by the artillery when ordered—everything’s got to be boneyard quiet, so no wagons, not even ambulances. Not until the attack’s begun to grip.” He nodded, as if weighing a small matter, then returned to the plan. “Wharton seizes the Cedar Creek bridge, takes the high ground, then he keeps on moving.”

With a smirk, he turned to Rosser. “Who knew the Laurel was a running vine, hah? If they don’t take off again, Rosser’s jockeys will fix the Yankee cavalry on our left, keep the bastards occupied. I want the Yankees looking every which way. All understand?”

The assembled generals murmured what passed for agreement.

Early turned to Gordon. “Anything else?”

“Bears repeating,” Gordon said, “that soldiers are to leave behind their canteens, cups, bedrolls, and any bayonets without full scabbards, anything that could make the least noise or slow a man. And no talking, to include officers. As far as the right wing goes, Jed Hotchkiss is out setting in guides at every point where the column could make a wrong turn, up to the Front Royal road, above the river. I’ll lead myself after that, I’ve walked the ground.”

He caught himself in an oversight: “And no horses for officers, not even generals. Not until we’re all across that river. Horses can follow the last of the infantry. One obstreperous horse could ruin everything, we need silence.” He judged the gathered faces, finding bloodlust, impatience, and at least a few traces of doubt. “Any matters not resolved to your satisfaction, gentlemen?”

“Boys are going to come out of that water cold,” Pegram said. “Nights have gone chill. And you have them crossing twice.”

Gordon shrugged. “No choice. Don’t worry, they’ll move faster to warm up.” He scratched his head, still purging refugees from the farmer’s clothes. His answer hadn’t satisfied Pegram, but all he could add was, “Speed will be everything, catch them in their tents. Keep moving, head for Belle Grove, take their headquarters. Tear their army apart before they’re even awake.” And pray to the Lord it works, he told himself. “Other questions?”

“John,” Ramseur spoke up, “earlier, you said Payne’s cavalry would meet us up along the Front Royal road. To clear the vedettes at the river and cover our flank. I’m assuming they’ll have their horses? Which means there’ll be noise, no matter what we do.”

“Payne’s taking a roundabout route, something of a feint. I’ve warned him to keep things quiet near the river.” Gordon forced a smile. “Not sure those nags of his have the grit left to make much fuss.”

There were no more questions. With orders to step off the moment darkness fell, every general wished to rejoin his troops, to set things in motion, and not to be the delinquent blamed for disaster. If disaster there was to be. And several men doubted the plan, that much was evident.

Plenty of fight in them, though. Gordon could feel it. They only needed a taste of winning again.

October 18, 9:30 p.m.

Belle Grove

“Only a few more, sir,” the aide commiserated.

Horatio Wright yawned. He had expected Sheridan back, but word had just come that the army commander would remain in Winchester overnight.

Unlike Sheridan. Had something gone wrong in Washington?

Well, there was always something wrong in Washington. And Sheridan was welcome to this job, he couldn’t come back soon enough for Wright. For all his experience as a corps commander, he hadn’t realized the full extent of an army commander’s less inspiring duties. The paperwork never ended, nor did the irksome demands on a fellow’s time.

Fighting a corps was a far better proposition.

He caressed his tired eyes with thumb and forefinger. “All right,” he told the aide, “go on. I’ll stop you if I want to read anything through.”

The aide bent close to the candles sheathed in glass. “Cavalry vedettes report a pair of men dressed as farmers acting queer. Across the river, near the Front Royal road.”

“Never knew a farmer who wasn’t odd,” Wright said. “Go on to the next report.”

October 18, 11:00 p.m.

Base of Three Top (Massanutten) Mountain

Ripping leaves from a screen of trees, the wind needled wet soldiers. After a maddening scare stirred up by Pegram, the right wing had made its first crossing of the river and thousands of men filed along the mountainside trail in careful silence. As if each of them grasped what was at stake.

This was a last chance, the last good chance.

Gordon tried to pay attention to each step and every crushed leaf, but he found his thoughts returning to Jubal Early. The old man had not resisted his final plan, not for a moment. It was as if Early had run out of spleen. And Gordon had truly seen Early, really seen him, for the first time in weeks, if not months. He had found a sharply aged man, with beleaguered eyes retreating under the barricades of his eyebrows. The skin around those eyes was tense and ruined, and Early’s hair had grayed markedly. Only his beard remained unchanged, as crusted and foul as ever.

Seeing the man so clearly had startled Gordon. It was as if he saw not flesh and blood, but a specter, a shade, of the nemesis with whom he had quarreled so bitterly. He’d never seen a being so worn through. Not with the mundane weariness of men marched or fought to exhaustion, but with a depletion of the very soul.

Gordon stumbled over a root. And as he regained his balance he came to his senses: Pity was an emotion for women and fools.