July 8, dawn

Monocacy Junction

“Sir, sir!” The orderly shook Wallace, none too gently. “I hear a train. Coming from Baltimore way.”

Wallace brushed off the man’s hand and rose, stiff and groggy, from the floor. He heard the swelling throb of a locomotive. God grant it be the veterans.

He pulled on his boots and fumbled with his coat, forgoing sash and sword. Ross had orders to stop any train that approached the iron bridge, but Wallace feared that his own two stars might be needed to settle matters.

The noise of the great machine grew huge, then screamed to a hissing stop.

Righting his hat, Wallace hurried out of the shack. Sleep’s claws pursued him: He’d known little rest for days. In the foreground, a locomotive steamed, impatient. Dark forms leaned from passenger car platforms and crowded the doors of freight wagons. Mist smoked off the river.

A figure alighted from one of the cars, moving with a haste that betokened anger: a big fellow, blacksmith brawny, followed by stumbling underlings.

Wallace strode toward the tall officer, who looked around as if anxious to land a punch. Sweat prickled Wallace’s back.

“What’s the meaning of this?” the new arrival bellowed at anyone who might hear. “Why has this train been stopped? What damned idiocy is it now?”

Wallace spotted Jim Ross, his senior aide and a newly promoted lieutenant colonel. Ross would be no match for the bull in blue.

Quickening his pace again, Wallace waved to Ross: Let me handle this.

“And who the hell are you?” the big man, a colonel, snapped. He marked Wallace’s shoulder boards, but didn’t recoil or salute. He merely lowered his voice to a muzzled growl. “You in command here?”

Wallace extended his hand. “Major General Wallace, Middle Department. To whom do I owe the honor?”

The scent of coffee rose from a cook-fire, teasing him. He wished he had been allowed a cup before this confrontation.

The big man paused, then accepted Wallace’s paw, enclosing it. “Bill Henry, Tenth Vermont. Why have my men been stopped?” He freed Wallace’s hand, which hurt. The colonel was short a finger, Wallace noted, and his uniform was hard used.

“You don’t have orders to stop here, then?” Wallace asked. “At Monocacy Junction?”

“None.”

Confined to the train, bleary soldiers eyed the two officers. One man emptied a slop bucket from a freight car.

“And your orders are?”

“Proceed to Point of Rocks. Either continue on the train, or march if the line’s interrupted. Report to Harper’s Ferry for duty at Maryland Heights.”

Wallace tried to judge the man before him, what his temper really signified. “And the Tenth Vermont belongs to?”

“First Brigade, Truex commanding. Third Division, General Ricketts. Sixth Corps.”

“Where’s General Ricketts?”

The colonel shrugged, stretching a bit. His complexion had been burned as brown as a pig turned on a spit. “Doubt he’ll be up before tonight. Hadn’t arrived in port when we entrained. What’s going on?”

A cup of coffee would have been a blessing. He would have liked to offer one to this still-seething colonel, too.

Hundreds of morning-blurred faces watched the exchange now, those on the train and more from the roused camp.

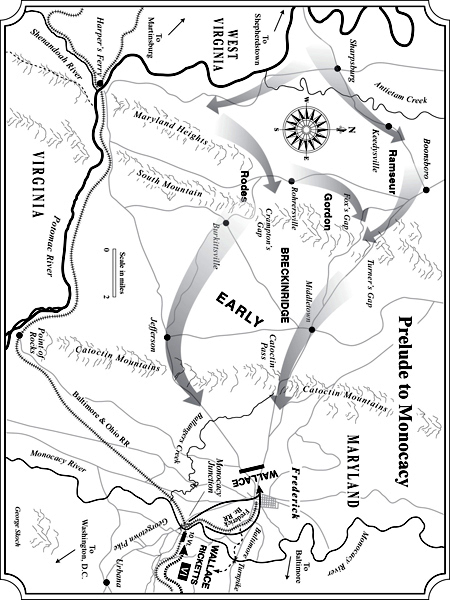

“Colonel Henry,” Wallace began in a confidential tone, “if you proceed to Point of Rocks—and if the line has not been cut by now—you will take yourself and your men away from a battle coming to this place today or, at the latest, tomorrow. General Early is going to sweep over the ridges to our west with a reinforced corps, and his men are going to march as fast as their legs can go for our national capital.”

Fending off sleep’s last grip, Wallace straightened his back. “I have twenty-three hundred raw recruits, and two hundred good cavalry. The enemy’s said to number between twenty and thirty thousand. That number may be exaggerated, but they’re veterans all. Yesterday, we held off their advance guard just west of Frederick. But if you and those coming behind you continue to Point of Rocks, they will overwhelm us and be on their way to Washington. And your regiment will have done no good to anyone.”

Wallace reached out a hand, but withdrew it before touching the other man’s sleeve. “I need you, Colonel. I don’t expect to beat Early. Just hold him long enough for Grant to reinforce Washington.” He met the man’s eyes in the seeping light. “I have no authority over your command. I leave the decision to stay or proceed to you.”

The colonel stared down at him for a dreadful stretch of seconds. Off to the side, Ross held still. On the cars, the soldiers, too, were silent, all their routine foolery suspended. As if they sensed—knew—that their fate was in play.

“Let my boys cook up some breakfast,” the Vermonter said at last. “And tell me where you want us.”

July 8, 9:00 a.m.

Fox Gap, Maryland

“They should’ve let us go, John,” Breckinridge said. “They just should’ve let us go.”

Erect in the saddle, as always, Gordon nodded. “Didn’t, though. And here we are.” He smiled. A gentleman always knew just when to smile. “Not a bad place at all, wasn’t for this dust.” He spread an arm toward the ripening fields that graced the valley. “All the bounty of Ceres.”

Before and behind the two generals and their staffs, long gray columns moved through tunnels of dust. Above the dirty air, the sun attacked.

“All the more reason they should have let us go,” Breckinridge told him. “Rich country, bountiful. The North has all it needs. Could’ve even spared us Maryland, way this Kentucky boy reckons.” He coughed. “John, I put it down to New York greed, Boston pride, and damnable Yankee spite. That’s what this war’s about.” He brushed dust from his long, slender mustaches.

Well, Gordon thought, pride and spite on our part, too, if love of a way of life in place of greed. None of them had expected this: the long years of blood and sorrow, of glory increasingly dimmed by lamentation. For months now, he had privately contemplated the possibility that the South might lose. He was in it to the end, all right, partly from pride and unabated anger, and partly in foreknowledge of what would fix a man’s status after the war, win or lose. But the probable end looked different to him now than it had before the slaughter below the Rapidan: The South was bleeding to death.

The man who failed to look ahead fell behind.

He wished he had a confidant to whom he could unburden himself regarding the prospects of the ailing Confederacy. But no man dared utter heresy or hear it; all had to pretend to a flawless belief that by some astonishing run of the cards the game would turn in their favor, even now. Many, like dear Clem Evans, truly believed it, discovering hidden victories in every defeat. Clem believed in miracles, divine or earthly, and Gordon had no wish to weaken his enthusiasm: He needed men who would fight without hesitation.

Gordon loved to fight. His concerns about the war’s outcome didn’t alter that. On the contrary, he knew full well that he’d miss all this immeasurably: Nothing so enlivened a man as a battle. A side of Gordon dreaded the end, the demotion back to mundane life and petty concerns. But he meant to be prepared for it.

He thought a bit more on Clem Evans, who planned to become a Methodist preacher and practiced by delivering camp sermons. Immaculate belief was a powerful thing. It was a gift the war had taken from Gordon.

No, he could never talk to Clem, fond as he was of the man.

He even had to be circumspect with Fanny, who possessed blind faith that he, her champion, could not be defeated. Evidence meant nothing to such as her; her confidence shone like Persephone’s in the Underworld. Nor would he deprive his wife of hope. When worse came to worst, her practical side would digest defeat and continue.

His splendid Fanny! She was as fine a woman as ever breathed, demure in the world and passionate in his arms, Penelope to his Ulysses. No, far better than Penelope, since Fanny had left their children in her family’s care to follow him through the war, to nurse his wounds and sew on his latest rank. She would not sit at home working her loom amid the cowards. Fanny believed in a distant Christ, but wanted her husband near.

Beside him, Breckinridge alerted, canting his head like a hound dog figuring things.

“That cannon?”

“Didn’t hear it.”

“Listen now.”

Gordon waited a fair time, then shook his head.

“Imagining things, I suppose,” Breckinridge told him. He mused for a bit, then added, “Johnson’s cavalry ran up against some militia yesterday. On the Frederick road. Gave him a fight, I hear.”

“I doubt Johnson gave anybody much of a fight,” Gordon commented. “I’m in accord with Early on that much. Johnson’s brigands aren’t worth a pail of oats. Cavalry’s not what it was. Best men gone, horses ruined.”

“McCausland, though, he’ll fight. Full of pepper, that boy.”

Gordon lifted a brow and sweat stung his eye. “Wouldn’t stop for a few militia, I’ll give him that.”

“Assuming they’re just militia.”

Gordon smiled, but with no trace of pleasure. “I’ve been pondering that question myself, if truth be told.” He pulled his horse away from the column. “Yankees have to figure this out, at some point. Sooner or later, it won’t be farmers in soldier suits anymore. And we’ll have a real fight on our hands.”

“Well, we’re ready for that, too,” his temporary superior told him. “Let them come on out and get whipped, they’ll find us ready.”

Ever alert to the nuances of companionship, Gordon reassumed his genial tone. “I expect so, General, I expect so. And I do hope to host you in Georgia, after the war.…”

Ahead, a soldier staggered to the roadside and collapsed.

“Killing this army,” Breckinridge sputtered. “Just killing it.” He turned his well-formed face toward Gordon. The man’s waxed mustaches were frosted with dust again. “You disagree, I know that, John. But I do believe we’re pushing the men too hard. They’re game enough, but the body’s a sight weaker than the spirit.”

Gordon knew it was fruitless to argue, or at least impolitic. Early brought out his combative nature, but Breckinridge was of a different breed, a gentleman. And like so many of his fellow gentlemen, Breckinridge was willing to push men to their deaths on the battlefield, but would not press them sufficiently hard to get them there before the foe was ready—and thus save far more lives.

No one since Jackson grasped the brute mathematics. Even if you lost one man in ten—or more—on the march, if you got to the fight before the Federals could double or triple their strength, you had the odds. It wasn’t hard figuring. And it was a remarkable thing, how much men delivered if they were soundly led. Soldiers just wanted a little show, a handful of stirring words and a flash of courage from the man giving orders.

Beside the road, the fallen soldier raved as they rode past.

“Poor devil won’t see Washington,” Breckinridge said.

Gordon wanted to tell him, “None of us will see Washington, if we give the Yankees time to shift their beef. We should have been across the Monocacy yesterday, rather than fooling with Sigel and tearing up rails.”

Instead, he said, “Hottest weather we’ve seen, I do believe. Prelude to Hades, and not even ten.” He lifted his hat to the nearest soldiers and poured the Deep South into his sonorous voice. “Weather here’bouts leave you boys mindful of Georgia? Y’all settling thoughts on home, way I am myself? Peaches near to ripe on the branch, and the Lord smiling down on the cotton? Win this war, and we’ll all go home a-grinning, that’s a fact.”

“Sure enough,” a voice returned. “Home, sweet home!” called another. A third voice rhapsodized, “Get me some of that sweet well water’n drink it till I bust.…”

Breckinridge sneezed. “I swear, John Gordon, you start in to praising Georgia again…”

Amazing, Gordon thought, that a political man who had been vice president of the United States and had run for the highest office did not understand the value of praising Georgia in front of Georgian troops. Not least when a man intended to go back home and run for a seat, if the bullets veered off. Let the war be lost or won, the political future would belong to veterans, whether they sat in the governor’s chair or stood behind it, out of sight of the Yankees.

Thinking on Washington again, Gordon pondered Early’s likely intentions. Despite Black Davey Hunter’s depredations before they whipped him back into western Virginia, Early kept a strict hand over the soldiers—of which Gordon approved. There had been no reprisals, at least not yet, for the burnings in Lexington and elsewhere, the wanton destruction and barbarism. He knew that Early intended to press the Yankee town fathers for ransoms, wherever he sensed full coffers and Union loyalties, but the soldiers were not to indulge themselves, a prohibition that occasionally demanded the wisdom of Solomon in its enforcement. Gordon approved of maintaining order and discipline—he would have no rampaging—but he also had sense enough to avert his eyes, nose, and salivary glands when his men cooked up fresh pork or a quarter of beef that appeared by magic.

Soldiers were like children, delighted to get away with small transgressions. One of the knacks of leadership was to know which mischief to ignore and when to descend upon a rogue like the Furies. The best leaders weren’t the soft ones who meant to be kind, but those who firmly punished misdeeds the soldiers themselves despised.

If they did get to Washington—get inside the city—what did Early intend? Old Jube wouldn’t say. Probably hadn’t decided, Gordon figured. For all his barking and snorting, Early had trouble making big decisions; Gordon had realized that way back at Gettysburg. The revelation had come as a shock, since making decisions came naturally to him, the way what to do in battle just seemed obvious. It had bewildered Gordon to realize that all those fellows with West Point educations did not see things that were plain as Aunt Sally. On a battlefield, what struck others as audacity was only common sense, as far as John Brown Gordon was concerned. And if you did not know what to do, you attacked.

Gordon never found leading much of a challenge. Following was another matter, though.

Well, he hoped that Early was shaping up a plan, since they wouldn’t be able to hold the city long, even if they took it. Have to destroy the military stores, of course, and put the right government buildings to the torch. The Navy Yard, certainly. That was part and parcel of war. Perhaps the Treasury, too. But the President’s House? The Capitol? Gordon recoiled at the thought of such destruction.

Yes, he had seen the ruins of the Virginia Military Institute. And Governor Letcher’s house had been burned to the foundation, his family prevented from rescuing heirlooms or even saving essentials. There would be no forgetting. But giving in to the impulse to retaliate was the opposite of strategy. And the South needed a strategy that weighed the possibility of defeat, with all its consequences. Vengeance was a very dangerous tincture, best administered in measured drops.

If they reached the streets of Washington, they would have to restrain the soldiers on pain of death. It was natural for the South to hate the North, given the years of Yankee depredations, but woe unto the South if the North learned hatred. Burn Washington, then lose the war, and only the nigger would profit.

The sun seemed hot enough to ignite fires. Still, Gordon felt they were lagging on the march. But he could do nothing, not with Breckinridge present.

He chafed, but smiled.

Adjusting his rump in the saddle, he asked, “Well now, Mr. Vice President … we do get to Washington, what would you like to do in that fair Thebes on the Potomac?”

“Take a bath,” Breckinridge said.

July 8, 4:00 p.m.

The western approach to Frederick

Why didn’t they come on? Wallace asked himself. They already had the numbers. What were they waiting for?

He steadied his sweat-glossed horse and scanned the horizon.

Days of little sleep had told on his nerves, and all morning it had seemed as though the Confederates were preparing to attack. Yet their probes had rarely risen above the skirmish level, and in the afternoon the Rebs had gone quiet. From moment to moment, he had waited for their guns to open, for gray ranks to swarm forward. But the attack never came, only odd encounters, as when a stray detachment of Reb cavalry somehow got into the streets of Frederick and collided with two squadrons of Clendenin’s troopers. Back for a parley with the city’s mayor, Wallace had nearly been caught up in the clash—which had kicked up so much dust the riders fought blind, lost souls in a maelstrom. In short order, the graybacks had found it politic to withdraw the way they’d come, disappearing after giving the town fathers a fright.

The mayor and his coterie had begged him not to give up the city to the Confederates, citing their loyalty to the Union and pleading that Frederick had already suffered, due to repeated Rebel visitations. Having witnessed the poverty of the South, Wallace barely refrained from chiding the men. If the war had harmed Frederick City, the wounds were invisible. Prosperity was evident on every side. Nor would he promise what he couldn’t deliver.

“I’ll do my best.” Those were his only words, carefully chosen. He knew he could not protect the city much longer. The real fight would come on the river, three miles south.

Military stores were being evacuated from the yards, and what could not be rescued would be destroyed. As for the convalescent soldiers in Frederick’s hospitals, not all could be removed … but the Confederates were not beasts.

He was proud of what he had managed to bring off. The little battle the day before had been splendid. Not only had Clendenin fought with art, but the Potomac Home Brigade had been unexpectedly stalwart, as had the strays and artillerymen he’d sent forward.

Now he had a veteran regiment in the line, those Vermonters, men with faces so darkened by campaigning that they might have been mistaken for U.S. Colored Troops. And regiments kept appearing down at the junction. Every hour that passed was an hour won.

Tomorrow would bring the reckoning, though. It could not be otherwise. Scouts had reported enormous clouds of dust just west of the ridges, clouds that betokened divisions on the march.

Nickering, his horse stepped back, then calmed again. Wallace patted the animal’s neck, taking its smell on his hand. The heat was monstrous. The Vermonters had set the example by stripping to their shirts, and the recruits had aped them. Wallace didn’t mind. But he felt that he had to remain in uniform himself, another of the pretensions rank required.

He remembered how, in his innocent years, he had written extravagant scenes of battle between Cortez and Montezuma The actions he had described seemed ludicrous now, impossible in their chivalry and glamour. He had captured neither the swift, brute shock of combat nor the grinding dullness that surrounded it. Even Mexico had taught him little, compared to this grim war that crimsoned a continent.

Captain Woodhull reappeared, returning from the Frederick telegraph station. He did not seem pleased with the world.

“Bad news, Max?”

“Yes, sir. I mean, yes and no.” The young man’s face was a Niagara of sweat. “Two more regiments arrived down at the junction. Makes five total, the whole brigade. With another brigade set to follow, maybe tonight, Mr. Garrett says. Colonel Ross wants to know if you’d like any more men sent up here.”

“No. No more. If we can bluff the Rebs until dusk, I mean to pull everyone back across the river.”

“The mayor—”

“The mayor’s a fool. Good Lord, does he really believe we could hold an army at arm’s length? Here? In the open? Does he want a fight in his streets?” Wallace shook his head. “If Early rides in quietly in the morning, the people of Frederick will fare a good deal better than they would under a bombardment.” Bunching a sodden handkerchief, he wiped sweat from his eyes. “What’s the bad news?”

“Telegraph operator ran away. The one in Frederick, not at the junction. I found the message from Colonel Ross on his desk.”

Wallace hooked his lips. “Wise man, I suppose.” He gestured back toward the townspeople with their carriages and parasols who, in defiance of his repeated orders, had clustered behind his lines to see a battle. “Wiser than those fools. Max, you try one more time to reason with them. If I go back there again, I’ll lose my temper.”

General Tyler steered his mount toward Wallace, but did not hurry the animal. Erastus Tyler had been put out to pasture, too, condemned to rot in Baltimore’s defenses, but the man had handled his little force magnificently the past evening and had been ready to stand his ground today.

All of them had done handsomely: Tyler, Clendenin … and Captain Alexander, with his pop guns. The fellow looked like a college professor, but handled artillery like a young Napoleon. All these men whom Washington had cast aside or consigned to the rear …

Would anyone think well of him when this was over? There had been so many setbacks in his life. So many failures, in truth. His father had turned him from home while still half a boy—not out of cruelty, but to teach the prodigal son a needed lesson. Having left many a school and quarreled with many a master, he had found himself copying legal texts to survive, earning his soup by piecework. Of course, the lawyer who took him in had been a family friend … but his father’s firmness had been a required tonic. Still, he had failed in his first, halfhearted reading of the law and gone off to Mexico. That had been the dawn of his serious life. Upon returning home, he had passed the bar, wed, and even prospered. But the greatest humiliation had been yet to come: his scapegoating after Shiloh, the sort of shame a man never quite lived down.

Tyler reined in. His mouth gaped.

“What I wouldn’t give for a good iced punch,” he said. “Whole bowl of it.” He lifted his hat, revealing a bald pate above his woolly beard. “Think they really mean to come this way, sir? They haven’t been showing much spunk.”

Wallace had begun to have his own doubts as the afternoon dragged on. Had the Rebs been laughing at him all the while, fixing him in place while they marched to Washington on a southerly route? Should he have let those veteran regiments continue to Point of Rocks? Had he failed again?

“They’re coming,” Wallace said, determined to be right. “They’re coming right over that ridge.”

Rather than look Tyler in the eye, he snapped open his telescope.

And there they were! Marching down three separate mountain roads, five miles away at most, endless columns surrounded by halos of dust.

“Look for yourselves,” he told the men beside him.

July 8, 9:00 p.m.

Early’s headquarters, Catoctin Pass

The tent did a fine job of trapping the day’s heat. Kept the dust off a man somewhat, but there was little more to recommend it. Did serve for a hint of privacy, but Early much preferred to borrow a house, when a house could be had. His quartermaster had picked out a site on the mountainside, though, hoping to snare a breeze. Hope hadn’t come to much.

By a lantern’s light, Early stared at Brigadier General Bradley Johnson. “Understand what it says there?”

The cavalryman looked up from reading the order. “Yes, sir. I understand.”

“Make all the noise you can. Burn bridges, army stores, anything touching the government. Make ’em believe the armies of Hell are headed their way and Baltimore’s doomed as Sodom.” He cackled, disdaining the sound of his own laugh, then sharpened his tone again. “Just leave the civilians alone, I’ll have no wantonness. You know this country, these here are your own people. Don’t go acting the fool.”

“Point Lookout?”

Early grimaced. “You read the order. You get down there and free those boys … if practicable. No damned foolishness, though. South don’t need any more dead heroes, category’s filled.”

Johnson nodded. Early had chastised the cavalryman for his dawdling before Frederick, only to have Johnson hurl back in his face Early’s admonition not to become decisively engaged or to do anything to suggest that their goal was Washington. Early lost his temper, couldn’t help himself. Few things enraged him as much as a cavalryman in the right.

Well, let Johnson and his band of thieves go roving. The sight of the mangy fellow was enough to set a man to missing Jeb Stuart, for all that fool’s shenanigans. Early would never have backed the fellow’s recent promotion to brigadier general, but Johnson had been a Breckinridge man in politics before the war, and the old ties remained.

Days were when Early feared politics alone would be enough to ruin the South, no need of Yankees. He’d had his fill of politics at that damned Richmond convention, but the filth of it all had followed him into the war. When peace came, he didn’t intend to run for any damned office.

“Don’t tarry, Johnson,” Early said. “Go on, see to your men. I’ll square things with Ransom.”

Johnson saluted and went out. Immediately, Sandie Pendleton entered the tent.

“God almighty,” Early said of Johnson. “Fool would sweet-talk a hoor he’d already paid for.” He sighed at the world’s inexhaustible frustrations. “Got ’em all rounded up, do you?”

“Yes, sir. General Gordon just rode in.”

Early snorted. “Gordon.”

Made him want a chaw. But there was too much talking to be done. Army full of lawyers, talk everything to death.

Pendleton held the tent’s flap open and Early crabbed through. Outside, the skin-gripping air was mean, but cooler than in the tent. The quartering party had pitched it with the sides rolled up for ventilation, but Early had made them drop the canvas again. Didn’t intend to sleep in the damned thing, just needed some privacy. Always said he didn’t mind shitting in front of a thousand men, but preferred to think in private.

Well, there they were. Scattered about the near-dead fire that no man wished to approach in the lingering heat. The last, small flames gave an orange cast to men’s faces, lighting them from below, creating devils. The air sparked with fireflies.

“All right, then,” Early said. “Sandie’s got your orders written down all nice and pretty, but I want you to hear the gist of things from me.” He scanned the shadowed faces, pausing briefly, against his will, at Gordon’s. Bugger always looked so damned superior, cock of the walk. The sight of Gordon made him gum a chaw that wasn’t there.

“Ramseur’s Division leads in the morning, stepping off at dawn.” Early faced the young general, who had removed his hat. It was too dark to make out much, but Early sensed the prematurely receding hairline and earnest eyes. “Any damned militia lurking ’twixt here and Frederick, you clear them out fast, Dod. And don’t stop, hear? Pass your lead brigade through town on the Baltimore road, as if that’s where we’re all headed. Make a demonstration, set them to quivering. But your following brigades will turn south for Monocacy Junction and seize the crossing. Fast.”

“What if they put up a fight on the Baltimore road, sir?” Ramseur asked. “Shall I engage? How far out should I push?”

“They dig in their heels east of town, it’ll be by the bridge. Only sensible place. No, don’t engage. Not seriously. Just keep ’em occupied, amuse ’em. I want those peckerwoods thinking on Baltimore burning, but I’d as soon have them run off and sow panic as meet their Maker.” Early grunted. “Make a little show of giving chase, they do run off. Mile beyond the river should be enough. But I don’t want your boys drawn into a shit-flinging contest, no point in it. General Rodes will relieve your brigade on the Baltimore road, he’s next in the order of march. He can take care of any proper fighting needs to be done, he’ll have some time. Upon relief, the brigade will rejoin your division.”

He turned to Rodes. “General, your division will cover this army’s left tomorrow. Any Yankees still fussing after Ramseur’s boys been relieved, you help ’em meet Jesus. Seize the Baltimore bridge, if it don’t look to cost you. Yanks get spooked and pull off, you cross the river, demonstrate toward Baltimore with a few regiments, and turn your division south.”

Early nodded at everybody and nobody, squinting to read their postures in the dark. These all were men who had seen the worst of war: There was no dread.

“Ramseur here will lead the march on Washington,” Early stressed, “a city I expect to set eyes on in forty-eight hours.” He glanced at Gordon, hoping to see disappointment, but Gordon’s features—what he could read of them—remained superior, aloof. Pale scar on his cheek a badge of pride. Why men thought Gordon affable, Early never could figure.

Returning his attention to Ramseur, Early added, “Dod, you just make sure the telegraph wires are cut before you turn south. Then you move fast on that junction, hear? Grab the road bridge and railroad bridge, both of them, and keep right on going. Any resistance down that way, smash it quick. Your boys can brush away home guards and militia.”

“If they’re home guards and militia,” Gordon put in.

Early turned on him, almost relieved to have the excuse. “Expecting the Army of the Potomac, General Gordon? Have I been inattentive? Did Useless Sumbitch Grant and Granny Meade sneak up on us? While I was at my Bible?” Exasperated despite himself, he turned to his chief of staff. “Sandie?”

Pendleton, a young man of pleasing manners, stepped forward and smiled at Gordon—with none of the malice Early knew his own smiles held in spades.

“General Gordon, we have had reports of veteran cavalry in the area. In limited numbers. That’s to be expected, you’ll agree. But a citizen of Frederick—whose sympathies lean in the proper direction—made his way to our headquarters to report there’s no one in Frederick but home guards. Hundred-day men and the like.”

“And when did this good citizen pay us a visit?” Gordon asked.

“Yesterday.”

“Yesterday,” Gordon repeated.

“Yesterday evening, to be precise. General Gordon, we have had no reports, no indications, of a significant Union force anywhere in our path. The Federals … do seem embarrassed.”

“And even if they’ve rounded up a herd of goddamned Regulars, Ramseur can handle them.” Early turned to Breckinridge, who seemed disinclined to enter the exchange. “Or does General Gordon have information he hasn’t yet shared with us? Maybe Sherman evacuated Georgia? To hurry up north and catch us by the tail?”

Breckinridge said nothing, but looked toward Gordon.

“I have no information,” Gordon said, “but sooner or later the Yankees—”

“Are going to burn in Hell,” Early said. Pulling back on his temper’s reins, he addressed Ramseur again, although he had meant to be finished with the business. “Whatever’s down along that river, you finish ’em off quick, and then you get along down that Washington road. We wouldn’t want to disappoint General Gordon.” His voice had ranged higher in pitch than he wished it. It always did when someone got his goat. He knew it, could predict it, but never could do one goddamned thing about it.

Mastering himself as best he could, Early shifted toward Breckinridge. “Your divisions will halt this side of the river. Until the others have passed. You will position General Gordon’s Division on the right side of the highway to Washington, where General Gordon can observe the army’s progress across the Monocacy and resume the march when ordered.”

Early knew he had just created more bad blood. He had not planned it that way, but Gordon had a genius for setting him off.

There was one last matter to which to attend.

“General McCausland? Where’s McCausland?”

“Here, sir,” the cavalryman said. “Just standing off from what’s left of that fire.”

“Yes, indeed,” Early said. “I have observed that cavalrymen tend to withdraw when things get hot. McCausland, you and your mule-jockeys cover the right. Minus Johnson. He’s setting off to cover himself in glory. Substantial amount of horseshit, anyway.” Early grunted pleasurably at the latter thought. “Uncover any fords not on Jed’s maps. Then get on down to Urbana, push right along. Clear the road for Ramseur’s boys—I’ll have no excuses—and screen the march. No reason you couldn’t reach Silver Spring come nightfall.”

The darkness had fallen heavily and the fire had faded to coals. His generals had become mere forms, highlighted by the occasional glint of a button or a belt buckle.

“Questions?”

Ramseur’s voice crossed the darkness. “Where will I find you, sir? If I need to report?”

Early smiled. “I mean to take my breakfast in Frederick, gentlemen. I have weighty matters to discuss with the local authorities … who I am convinced desire to make a substantial contribution to the Confederate States of America.” He cackled again. “Under threat of seeing their fair city put to the torch.”

* * *

After Early retreated into his tent, Gordon sought out Pendleton.

“Sandie … for God’s sake…”

“He doesn’t mean it, sir. He has no mind to burn Frederick. But the moneybags in Frederick won’t know that.”

The fireflies blinked like skirmishers. Gordon believed he could actually smell the heat.

“And Washington?”

Pendleton hesitated. Gordon could just discern the chief of staff’s features, not well enough to read them.

“He doesn’t say,” Pendleton confided. “But I hardly think—”

“Sandie, Jackson made you. And you helped make Jackson. You know we’ve been dawdling along. Oh, the marches themselves are hard enough, I’ll admit that under duress. But they haven’t been direct, they haven’t gone anywhere. We’ve been fiddling around with no-account Yankee detachments and minor supply depots, splitting off in every direction and tearing up rails we could just as well rip up later. And now we’re behind, by my reckoning. Sooner or later, even the dumbest Yankee in Washington is going to get some inkling of what we’re up to.”

Infinitely frustrated, weary, and crusted with sweat, Gordon continued: “And what on earth is he thinking, Sandie? He and I have our differences, but we’re not enemies. We’re both on the same side in this blasted war, last time I caught up on the Richmond papers.”

Pendleton stood stock-still, a barely breathing outline in the darkness. Gordon knew that the young man was wise far beyond his years, an expert judge of his fellow man, and skilled at measuring just how much to say. But he and Gordon had been in agreement many a time over the months, even when the chief of staff declined to support Gordon’s position publicly. Pendleton had not survived Jackson, Ewell, and now Early by offering strong opinions. The boy had physical courage, more than a surfeit. Uncanny judgment, too. But speaking up just wasn’t in his blood.

Voice low as a regicide’s, Pendleton said, “Lynchburg, the business in the Valley … now this … this raid or invasion, or whatever one may call it … it’s his first independent command, his first truly independent command. And he’s done pretty well, up until now. But with every success, the possibility of failure…” Pendleton shook his head, slowly, a dark shape in dark air. “Consider the responsibility, the weight he’s feeling. We’re all Lee could spare—and the truth is Lee really couldn’t spare us, either. General Early loses this army, and he’s the man who lost the Confederacy, that’s how he looks on things. On top of all that, he’s measuring himself against Jackson, he can’t help it. He’s just—”

“Jackson would’ve been in Washington by now.”

“You don’t see all the orders he receives from General Lee. Some … border on the fantastic.”

“Sandie, every hour we waste we’ll pay for in blood. Or failure.” Gordon folded his arms. “Or both.”

“He smells Washington now, he’s got the scent. He wants to get on with things.” Again, Pendleton hesitated before speaking further. “You really shouldn’t badger him, sir. It doesn’t help.”

“We should’ve been across that river yesterday. If he only would’ve—” Gordon caught himself sounding like a spoiled child, if not a bully. There was much in what Pendleton had said, he’d known it all before the boy spoke one word. But so much went back to that lost day in the Wilderness, the missed opportunity …

Gordon softened his voice and his stance, serving up a portion of geniality, however thin the crust.

“I do ride on ahead of my horse sometimes,” he said with a smile meant to be felt, if not quite seen. “Sandie … if there’s any way I can help the man … genuinely help him…”

Weighing his words again, Pendleton said, “I’m sure you’ll get your chance, sir.”

July 9, 1:00 a.m.

Monocacy Junction

Weariness pinned him to the floor, but Wallace couldn’t sleep. When tired, he slipped too readily into pessimism. And he was morbidly tired.

Two additional regiments had arrived from the Baltimore docks, with claims that the rest of their division was on the way from Virginia. Nonetheless, he felt less confident than he had before the first veterans appeared, asking himself yet again if he was being vainglorious, demanding that men die in a hopeless fight. Was this about redeeming his reputation, even as he lied to himself that the battle’s outcome must ruin him? Was all this born of the romance of novels, a child’s dream of a gallant forlorn hope? Played out at the expense of other men’s lives? The visions that kept him from sleep conjured slaughter and panic, fleeing men and disaster. Nor did the vermin haunting the blanket that served as a mattress soothe him.

Was this what theologians meant by the dark night of the soul?

Or did he just need sleep?

The withdrawal from Frederick had gone smoothly, untroubled by the Rebs. The townspeople had been furious, though, cursing him and the troops they had recently cheered. Wallace consoled himself by recalling the cries of “Go ahead! Run for Baltimore!” That was precisely what he wanted people to tell the graybacks when they arrived, that he had withdrawn his small force toward Baltimore, his little ruse. And then he would be waiting for Early when the Rebs strolled down the Washington road.

Even that slight surprise might help, buying an extra hour.

He turned from one side to the other, feeling uneven planks through the blanket’s nap. Another creature scurried along his calf, making him jerk and slap at himself. The heat’s embrace was smothering.

As sleep teased Wallace, Ross stumbled in. He looked a sorry wreck, but had insisted on keeping his post.

“Sir?” His voice rasped. “General Ricketts is here, he’s just behind me.”

Wallace sat up and fumbled to a knee. “My coat.”

Before he could dress, Ricketts entered. The division commander wasn’t especially tall, but broad enough to give the door frame a fright. By candlelight, the man had an Irish look of the hardest sort.

Wallace held out his hand. The other man slapped his own hand against it, gripping firmly but quickly letting go.

“General Wallace? Jim Ricketts. I hear Early’s on the loose.”

“He’ll be in Frederick by morning. Three miles from here.” Wallace thought for a moment, rubbed an eye. “He could be there now.”

“I suppose I’m in it, then. What’s Early’s strength?” There was absolutely no nonsense in the division commander’s voice. “Railroad fellow made it sound like the Mongol Horde was upon us.”

“Reports claim twenty to thirty thousand, so I figure fifteen to twenty.”

Ricketts nodded. “Sounds right. What exactly do you intend to do?”

“Fight.”

“Here?”

“Here.”

“How many men do you have? Of your own?”

“Twenty-five hundred, a few hundred of them veterans. You?”

“Five thousand. Total. When my last regiments arrive. And that’s counting every cook.” Ricketts shook his head. “Don’t care for the odds. Good position?”

“The best defensive line between Frederick and Washington. You’ll see it, come first light. Meanwhile, Colonel Ross can guide any more troops who come in, he knows the ground.”

“And your objective? In making a stand?”

Wallace fought a yawn and lost, but there was no point apologizing. “Three things: First, I want to know for sure whether Early’s on his way to Washington, or if he’s headed for Baltimore, after all. That drives every subsequent decision. Second, I want to push aside the curtain and find out how many men he’s really got. I mean, good Lord, he’s marched all the way from Lynchburg, and no one’s certain what his force consists of.” Wallace tried to shake off the weariness gripping him, to speak cogently, urgently. “Third, if his objective is Washington, I want to hold him up as long as possible, give Grant time to transfer a corps or two and save the city.”

Ricketts stared straight into his eyes. The fellow was cold as an iron bar in January. He considered Wallace’s words, then asked, “You have a plan? That includes my men?”

Wallace nodded, escaping his weariness in a burst of enthusiasm. “And excellent ground, truly splendid! Since your men began coming in, I’ve shifted my green troops to the right, to cover the fords to the north and the bridge on the Baltimore road. It’s a great deal of ground, but the terrain’s steep this side of the river, and there aren’t many fords up there. I’m gambling that Early’s not going up that way.”

Struggling to keep his own eyes steady, he met Ricketts’ gaze again. “Your men will concentrate here, as my left wing. There’s a covered bridge on the Washington road—you could see it from the porch, if we had some moonlight—and an open-deck rail bridge off to its right. Early intends to cross right here, I’m convinced of it.”

He raised his hands in excitement, as if about to grip Ricketts by the coat. “There’s good ground to anchor the left of your position, I think you’ll like it. Open fields, but higher than the north bank, you’ll have the advantage.” A nervous smile overtook his features and he realized his hands were shaking. “You’ll see it all at first light, I’ll show you everything. I believe we can give them a time of it, General Ricketts. We’ll give them a time.…”

“I have no guns,” Ricketts said with a first, faint hint of emotion. “I was ordered to leave my artillery at Petersburg. I’m a damned artilleryman, and I don’t have a single battery.” He shook his head, becoming human at last. “Don’t have one ambulance, either. Or my field surgeries. I have to believe we were meant to fill up the Washington forts. Before things came undone.” He glanced down at the planks and looked up again. “What kind of artillery do you have?”

“One battery, six three-inch rifles. And one good howitzer.”

Under Ricketts’ whiskers, his mouth formed an acid smile. “Early will hardly be able to claim you had an unfair advantage. Cavalry?”

“Five squadrons of the Eighth Illinois. They’re well officered. And some mounted infantry.”

“So … if my entire division closes … we’d have seventy-five hundred men, at most, a third of them green as shamrocks, with no artillery to speak of and not enough cavalry to picket a field latrine.”

“I do have ammunition stacked. And a train waiting back of the hill to take off the wounded. And we have the river to our front, it’s really a splendid position.”

“And your position is how many miles long?”

“Three. Approximately. A bit more.”

Ricketts sighed. “General Wallace … we haven’t the chance of two mice facing a regiment of cats. You realize this is madness?”

“Yes. I do.”