8:45 a.m.

Eversole’s Knoll, off the Berryville Pike

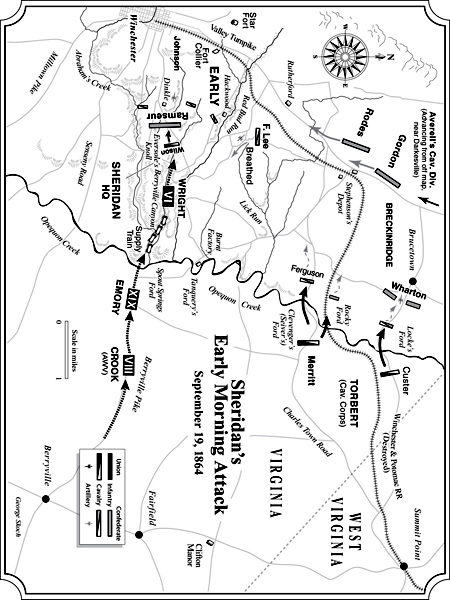

Sheridan struggled to keep his temper. The last of the Sixth Corps divisions—Davey Russell’s lot—had just emerged from the gorge, well behind schedule. It was a good thing, Sheridan told himself, that Wright had gone forward to guide Ricketts into position, or the corps commander might have gotten a tongue-lashing that cut bone.

Damned muddle. All of it.

Sheridan’s approach to leadership was crisp: You never showed fear or doubt; drove subordinates hard, but praised them generously; cut down threatening peers; and gave your superiors victories, damn the cost. But many a day he was tempted to strip the skin off a general or colonel serving under him. Today, Horatio Wright wanted a flaying. To say nothing of Emory, whose Nineteenth Corps seemed to have disappeared.

Quick-marching along the Pike, the regiment leading one of Russell’s brigades soon spotted Sheridan. The men cheered, and Sheridan waved, offering his troops a practiced smile. He made out Upton, a brutal babe in arms, chiding the soldiers forward. Sheridan valued Upton. Despite the lad’s dreary fondness for Bible verses, the young brigadier was a killer, Old Testament, not New. Astride his roan he looked savage as a Comanche.

But the rest of the day’s business crawled, as if his army were a mule of a mind to test its master. Wilson’s cavalry had done its work, securing the mouth of the gorge and knocking back Ramseur’s boys from their forward positions, but even those early attacks had gone in at much too slow a pace. Now the situation demanded infantry to finish off Ramseur before Early reinforced him.

As the army slogged up through the “Berryville Canyon,” Sheridan’s plan had begun to come apart. It made him burn. The war had taught too damned many officers caution. Audacity and ferocity won battles, the Rebels saw that much.

He had realized, too late, that inspiriting an entire army was an altogether different matter from instilling dash in a few divisions of cavalry. For the first time, the scope of his new command seemed daunting: What if, after so many triumphs, he failed?

George Crook had been right about trusting a single road, and that galled Sheridan, too. He liked Crook and respected him, but remained alert to hints of Crook’s old seniority. Before the war, Crook had been not only his superior officer, but something of a friend. And outward friendship still prevailed, with Crook behaving impeccably. Somehow, that made things worse.

In an instant of weakness, almost of panic, he imagined himself relieved and Crook replacing him.

Sheridan stiffened his spine: That would not happen.

He had passed so many officers on his climb, though. Even Davey Russell, his captain early on, was stuck leading a division under Wright. For all the good cheer his old comrades displayed toward him, Sheridan could not help feeling that more than a few would have liked to see him fail.

Unjust suspicions? Perhaps. But an officer didn’t win stars through Quaker forbearance. Life was a constant battle. Every man born short of stature—and every Irishman—learned that out of the cradle: A man got what he had the grip to seize.

In the fields and gullies off to the west toward Winchester, skirmishers pricked the morning. Wright’s lines filled out at last, their dark blue almost black against the greenery, and batteries unhitched between the groves. Well and good, but time was pressing hard.

And Wilson’s horsemen had gained this ground at a cost. John McIntosh had been shot in a clumsy attack. Sheridan had ridden up to the wounded man’s litter to tell him, volubly, that he had done nobly, but the cavalry action had been a piecemeal donnybrook, victorious only because of initial surprise and swelling numbers. A sound brigadier, McIntosh would lose a leg. Sheridan had pressed Wilson’s troopers forward for as long as it made sense, but now it was the infantry’s turn at work. And, veterans or not, Wright’s soldiers had the slows.

Below Sheridan’s hillock, a break developed in the flow of troops. Unwanted wagons creaked out of the gorge and paused, waiting for orders, blocking the road. Sheridan had expected Emory and the Nineteenth Corps to appear, ready to outflank the Rebs on the right.

If Emory didn’t emerge from the maw of that gorge at the double-quick …

And what the devil were all those wagons doing, clogging up the egress from the gorge? He’d ordered the trains to bring up the army’s rear, he’d made it clear.

Sheridan’s staff men kept well off him: They’d learned to read his moods. And when still more wagons—whose damned wagons?—appeared in place of regiments and brigades, a livid Sheridan turned to order an aide with rank to ride back and attend to the problem.

Then he decided to gallop down there himself.

“Flags stay here,” he snapped. “Forsyth, Moneghan, ride with me. Bring two couriers.”

He spurred Rienzi toward the Pike, waving his hat to troops who cheered to acknowledge him. His smile was as forced as an old man’s shit.

The soldiers had to believe that he was confident, that he had the day in hand. A bold smile at the proper time could be worth a full brigade.

Where the hell was Emory? Even Old Bricktop could not have strayed from the single road assigned him.…

Galloping through a fog of wagon dust, Sheridan pointed his mount toward the gorge, cursing Heaven and earth in anticipation. He promptly became entangled in the worst confusion he’d seen on the verge of a battle. Avoiding a crowd of purposeless men, his horse nearly collided with an ambulance. A less skilled rider would have been hurled to the ground.

The declining road was Hell under green leaves, cluttered with every encumbrance that burdens an army. Supply wagons and spare caissons swarmed the narrow Pike, wheels interlocking. Drivers raged and whipped each other’s teams to clear the way, making things worse. Put-upon men fought bare-knuckled, while others loitered, content to avoid the fray pending in the high fields. There wasn’t space for a rat between the flank of the hill and the drop into the ravine. Still worse, some idiot surgeon had set up shop at the one spot where wagons might have skirted each other.

A pile of arms and legs stood near the road, souvenirs of the cavalry attack and hardly the welcome Sheridan wanted for troops headed into battle.

The wagons belonged to Wright’s Sixth Corps, their presence a flagrant violation of orders.

“Satan’s whore of a mother,” Sheridan muttered. “Buggering Christ.”

He bullied his way down the narrow Pike, ordering idle men to clear the way, although they had nowhere to go. At last, he spotted Emory forcing his way up the track with faint success. Emory had lost his hat. His red hair spiked.

As he closed on the general commanding the Nineteenth Corps, Sheridan exploded.

“You shit-licking bastard. You’re supposed to be up and ready to attack.”

Emory was having none of it. He leaned out of the saddle as if about to punch Sheridan in the face. “I’m not going to be your whipping boy, Sheridan. If you want to know where my soldiers are, just look up that damned hillside. I’ve had to set my men scrambling through the brush to get past this mess.”

“These wagons aren’t supposed to be on this road.”

“Well, they’re not my goddamned wagons.”

“I know whose wagons they are.”

Sheridan wanted to smash somebody, something, anything. Wright, who had it coming, wasn’t there, and Sheridan couldn’t restrain himself.

“This is your goddamned shambles, Emory. As the senior officer on the spot, you should’ve damned well taken charge and cleared the lot of them off.”

Emory gave him another hard-boy glare. “I told Wright to his face, back across the creek, that his trains were to wait while my men went forward. Care to know what General Wright replied?”

“Don’t you dare lecture me, Emory.”

“He reminded me that you’d placed him in command of the field this morning. And he ordered me to damned well wait my turn while his trains went forward.” Emory’s eyes belonged to a wolf. “In fact, I’m violating my orders by trying my damnedest to get past all this.” He jerked a thumb toward the army’s rear. “I’m supposed to be back there, sitting on my saddle sores.”

Sheridan found it unbearable to be caught in the wrong. He turned and called to Major Moneghan. “Find the provost marshal. Any of his men. Tell them to clear this road. If a wagon’s stuck, push it into the ravine. Hell, push them all over. Just clear this road.”

He turned back to Emory. “Get your men up that hill and into position.”

9:00 a.m.

Brucetown

After a ride much lengthened by poor information, Sandie Pendleton finally found the generals. Breckinridge and Wharton stood talking on the porch of a ruined store.

“Compliments,” Pendleton gasped, saluting briskly. “General Breckinridge, you’re to withdraw your infantry from this position and move to Winchester with all possible speed. Yanks are pressing Ramseur. It appears to be a significant attack.”

“Plenty of damned blue-bellies up here, too,” Wharton objected. He was leading Breckinridge’s Division while the former vice president commanded the army’s wing. “At least two divisions of cavalry. With those damned repeaters. Our cavalry can’t hold ’em, can’t begin to.”

“You have General Early’s orders,” Pendleton told him, a tad too curtly. He was as short of patience as of breath.

Squinting against the sun, Wharton looked up at him. Evidently seething, but restraining himself. “Tell General Early I’ve been hotly engaged since dawn … in an effort to prevent a large body of cavalry from crossing the Opequon. To no avail. We’re now attempting to hold them close to the creek. There. Now you have it in prettied-up language, fit for a staff report. But I’m telling you plain as calico, Pendleton, if I withdraw my infantry, their cavalry’s going to run all over us, once we’re in open country. I can fight a time where I am now, but if I pull out too soon, we’ll have a disaster. And not just for this division.”

Pendleton never had cared for Wharton, who was given to unkind remarks about staff men. “Doesn’t sound like much of a fuss to me, General.”

Breckinridge tried to smooth things over. “Sandie, it’s been plenty hot up here. You rode in during a lull. They’ve been coming at us hard, on multiple approaches. Plenty of them. They’ll surely come again, any minute now. We need to hold them east of the Valley Pike. Or this entire army will be outflanked.”

Pendleton could see it. All too clearly. But the situation at Winchester was desperate and worsening. The decision was General Early’s to make, no one else’s.

With a dust-scathed voice, Pendleton said, “I’ve given you General Early’s orders. He expects you to obey them.”

He pulled his horse around before the generals could renew the argument.

* * *

Wharton turned to Breckinridge. “It’s plumb insanity.”

Breckinridge shook his head, dismayed. “If Early were here, he’d see it.”

A few fields away, Yankee bugles sounded the charge again.

“Not sure how long we’ll hold, as it is,” Wharton noted.

“’Long as we can, Gabe,” the former vice president told him. “’Long as we can.”

10:30 a.m.

The Winchester battlefield

Fitz Lee didn’t want any man to know how ill he remained, but he half believed he should bind himself to the saddle. The dizziness wasn’t constant, that was a mercy, but his head felt the size of a pumpkin and as delicate as an egg. The day was mild—perfect fighting weather—but he remained greased with sweat. Wiping his forehead to spare his eyes, he rode as hard as he could bear to ride. Determined to do his duty.

He rode well enough to leave Breathed’s horse-artillery battery hundreds of yards behind, along with the mounted detachment guarding the guns. Only Breathed himself kept pace with Lee. The artillery major had a flair for horsemanship and war that belied his prewar training as a doctor.

Lee could have used the young man’s medical skills, but gunnery took priority this morning. The boy-faced major had left his Maryland home to establish a medical practice in Missouri, only to hasten back as secession spread, coincidentally sharing a railcar with Jeb Stuart and thus deciding his fate. The joke current in the cavalry was that Dr. Breathed dissected Yankees with shrapnel, but the young man’s taste for war went even further: He relished defending his guns with pistol and saber.

Lee often marveled at what war revealed in men, but the revelations could also be unsettling. He wondered how one such as Breathed could ever again find contentment in smearing ointments on children or giving ear to a woman’s vague complaints.

Every surge of Lee’s horse seemed a ruffian’s blow, pounding his spine. But he would not relax his pace. Desperate to seize the terrain he’d scouted earlier, he galloped headlong toward the fine, high field. Longing to lie down and to shut his eyes.

The Yankees, however, had chosen to be inconsiderate.

The queer thing was that they’d been massing all morning, a multitude, but Sheridan had yet to advance his body of infantry. It made no sense, since the Yankees had the numbers, plain as Hazel. Ramseur was stretched to the point of opening gaps of twenty, even forty, yards between regiments, with no reserves, just praying that Rodes or Gordon or Breckinridge and Wharton would appear. The Yankees overlapped his front, they had the weight to crush him. Yet they didn’t come on.

Hadn’t studied the terrain, either. Or if they had, they’d drawn some poor conclusions. That was one dispensation from the Lord. The Federals appeared set to rest their flank in the fields south of Red Bud Run, a creek down in a chasm, with no attempt to secure the heights to the north. And that ground had been wrought by the Lord for artillery.

“Over there,” Lee shouted, hoarse and breathless, barely able. “Major, put your guns in battery over there and aim due south.” He drew up and Jim Breathed reined in beside him. “Attend to this personally. Plenty of Yankees will make their appearance shortly.”

Breathed snapped open his field-glass case, intent on a better look.

“Oh, they’re over there,” Lee assured him. He coughed.

“And fool enough to cross those fields?” Breathed asked, pointing. “I’d have them in perfect enfilade.”

“Knock ’em down in rows.”

With Breathed leading this time, they trotted to the lip of the field above the creek. Behind them, arriving cavalrymen eased their pace, husbanding hard-used nags, with four guns and extra caissons rattling behind them.

Lee intended to linger just long enough to see the battery positioned, but not a moment more. He had to ride north, see how Lomax was faring. The din of action, including the thump of artillery, rolled down from Stephenson’s Depot and the countryside beyond. According to reports he’d received, two Yankee mounted divisions were in action to the north. Lee foresaw an attempt at a grand envelopment, imagining advancing waves of blue. He commanded less than half their number, shamefully mounted. And the Yanks had their infernal repeating rifles.

Well, if a man couldn’t be strong, he’d best look strong.

If only the blasted dizziness would quit ambushing him.…

He just had to stay in the saddle, only that. His uniform clung, sodden, drenched by a private rainstorm. He prayed to stay upright through this fearsome day.

“That’s right,” he called to a sergeant. “Set her in just so.” Breathed’s cannoneers looked like filthy workmen, not the proud soldiers Lee knew them to be.

He felt himself wobbling again, the whole world tilting.

“You all right, sir?” Major Breathed asked.

Lee tried to smile, unsure if he succeeded. “Just pondering the lot of Man the Fallen, Major. And the frightful justice of the Lord.”

“Put a few rounds in those trees? See what they’ve got in there?”

Lee stared across the ravine, focusing by strength of will. The Yankees were out there all right, deep in that grove. He’d seen them marching up from another vantage point. But the terrain was broken, rolling and plunging, with patches of trees interrupting lines of sight. Entire brigades could play peekaboo like children. It was a landscape that favored the artful defender. And Breathed’s guns held the only perfect artillery position Lee had found all morning.

Why didn’t the Yankees come on, though? What were they waiting for? Did their delay serve a purpose? If so, what could it be? Was Early doing exactly what they wanted, hurrying down to Winchester? The blue-bellies could’ve crushed Ramseur hours before, with the strength they’d already had up.

Well, their delay was going to cost them dearly.

Lee closed a palm over his eyes, trying to force the world back into good order.

“Sir? Shall I give them a few rounds?” Breathed asked again.

“No. Don’t warn them. Surprise them.” His empty stomach burned, but he doubted that he could keep down as much as a biscuit.

“Sir … if I may speak as a doctor…”

“A minor indisposition, Major, all but behind me now.” Lee considered the dismounted cavalrymen deploying in skirmish order to shield the guns, weighing the meager force he had provided. There just were not enough men to go around. Not enough of anything, really. Except spirit. And even that, were the truth to be told, was not all it had been. “Can’t spare any more cavalrymen,” he told Breathed. “You’ll just have to make do.”

“Yanks try coming up out of that ravine, I’ll prescribe a dose of canister.”

To the north, miles off, the sound of fighting intensified. Lee imagined sabers clashing with sabers. He needed to be there, not here any longer.

About to ride off, he wiped his beard and addressed the horse-artillery major a last time.

“Hold this position, son,” Fitz Lee told Breathed. “You hold this position.”

11:00 a.m.

The rear of Sheridan’s army

Rud Hayes rode at the head of his brigade, confounded by the beauty of the day. Beyond the dust of an army on the march, a mild sun flirted with autumn. Dreaming of colors to come, the green groves slept. Fields gleamed and cornstalks faded. The earth, the air, emanated a grace past understanding, the transcendence philosophers struggled to explain. Swedenborg, Emerson, it mattered not: The language of men could not confine such wonder, this brilliance of life.

It often struck Hayes how nature remained unmoved by human folly. Up ahead, cannon grumped—not yet with the full growl of battle—but these fields would meet soldiers or lovers impartially. It put Man in his place.

Men were such small things, really, measured against the stars, and yet each life was the center of a universe. In West Virginia, they had clashed in a war of ants atop mountains as grand as Eden. Men had perished miserably amid splendor, and those who gave them orders could only hope their deaths had a greater meaning, that this hard war made sense.

Riding by his side, Russ Hastings asked, “Think we’ll go in, sir?”

Hayes judged the distant smoke. “Only if things go badly.”

The young man longed to prove his worth, to show that he could rival Will McKinley’s skills as an adjutant, but Hayes felt no craving to see his men bloodied again. If they remained out of the fight this day, it would bring no shame upon them. They had done their duty before and doubtless would do it again. But killing had to be confined to duty, never a matter of personal advantage. This murder condoned must not become a passion.

In the early days of the war, it had alarmed him that men killed so readily, then gloated. Sometimes he felt that the true purpose of discipline was not to get men to fire when ordered to do so, but to ensure they ceased firing when that command was given.

Hayes had never caught the contagion of common religion, but there had been times in this war when he feared for his soul.

He could not deny that battle thrilled the senses—disturbingly so—but he never lusted for it between-times. Content to follow orders, he did his best when required, and that was enough. He knew too many of the men he led, not only by sight and name, but in the deeper ways rooted in shared hardships and winter encampments. No glory gained at their expense appealed to him.

Nor could he feel hatred toward those across the lines. He would fight them and kill them because it was a necessity, because his cause was true, however scarred. But he could not, would not, hate them. Instead, he worried over Southern friends. He hoped, when peace returned, to renew acquaintances from his Harvard days and others forged of convivial evenings back in Cincinnati. How could he hate Guy Bryan, all but a brother?

He longed to see Guy again, whether in Ohio or Texas, and he hoped that Guy could put his own rancor behind him. Surely this war would long haunt its survivors, but Hayes did not mean to let it master his span, should he be spared. War might take his life, but it would not blunt his affection for his friends.

A pair of birds winged through the dust. Hayes wiped cracked lips with a rag. His boils bit.

At times, it seemed that the greatest challenge was not to defeat those who wore a different uniform, but to avoid becoming a man of demeaned worth. If he could not share Lucy’s Methodism, he certainly shared her faith in goodness and honesty, in the value of dealing justly with all men. If a fellow could not be great, he could be good.

War made that hard.

Hard, but not impossible, and Hayes refused to give in. Even in politics, he had proved that a man need not be craven. If politics asked compromise, it need not feed dishonesty. In this brief life, all a man possessed of value was his character. That and the love of those who adorned his life.

Lucy, above all, Lucy! He dreaded disappointing her as other men dread Hell.

A courier hastened toward him, raising dust within dust.

His brigade had not received its marching orders until well into the morning, hours after even he had expected to go forward. All matters had run late, which meant that blistering urgency lay ahead.

To live amidst war was akin to enduring a plague year: The man who rose hale and merry at dawn could not know if he would live until the evening. Dafoe would have understood.

The courier could not stop his horse and pounded past Hayes and his staff before managing to halt his mount and turn it.

“Begging your pardon, sir,” the lieutenant cried, “General Crook and Colonel Duval request your presence up yonder at the crossing.”

“How do things look?” Hayes asked.

Gleaming with sweat, the young man answered, “Confused.”

11:15 a.m.

The Union line at Winchester

Despite the presence of the man’s brigade commander, Ricketts felt compelled to speak directly to the major leading the 14th New Jersey now:

“You’ll be the man at the heart of it, Vredenburgh. This division’s at the center of the advance, the flanking divisions guide on us. That makes your regiment the unit of direction. Do not veer from the line of that damned road.” He pointed at the Berryville Pike. It led out past the skirmish line, where trees and smoke obscured it. “Follow it, if it leads to the Pit of Damnation. And maintain contact with Getty on your left. You understand?”

The major nodded. Vredenburgh had performed heroically at Monocacy, but this was another day. It irked Ricketts that despite his efforts to rebuild his division, he still had majors and even captains leading regiments. While no end of colonels prowled the army’s rear.

Bill Emerson, the man Ricketts had moved up to replace Truex as his First Brigade commander, felt obliged to put down a few cards:

“Just hug that road, Pete,” Emerson told Vredenburgh. “Put your color guard on it and tell them to stay on it, or you’ll blow their brains out yourself.”

That was hardly the tone to take when speaking of good men. Ricketts nearly fired off a remark, but restrained himself: Too late now to propound a theory of leadership.

Ricketts’ mood had turned surly enough as his watch ticked round the hours. A day that had started off well enough, with ham biscuits and fair weather, was turning as ugly as a squaw with smallpox. The entire Sixth Corps, in position for hours, had waited all this while for a single division of the Nineteenth Corps to appear, at last, on its right. Ricketts did not doubt that the delay would prove worth more than a division to the enemy.

Had Sheridan possessed the manliness to attack with the Sixth Corps alone, Ricketts was certain they could have crushed the meager Reb defense. With Getty on his left and Russell in reserve—without Russell, for that matter—they could have struck the Johnnies like an avalanche. But Sheridan, despite his swagger, moved with a spinster’s caution. Limited to prodding the Johnnies with skirmishers, Ricketts had watched as Reb artillery rolled into position, battery upon battery. And the guns, no doubt, would soon be followed by infantry. If Reb reinforcements had not already arrived. With the broken terrain, the swaybacked fields, odd groves, and overripe cornfields, the ground over which he had to advance was a division commander’s nightmare.

Couldn’t Sheridan see it? Why hadn’t he struck the Johnnies early and hard? Their line had been thin as rice paper.

“All right, Major,” Ricketts told Vredenburgh. “When you hear the advance sounded, move immediately. We’ve lost too much time already.”

“Yes, sir. New Jersey will do its duty.”

Profoundly ill-tempered, Ricketts almost said something completely unfair. Again he controlled himself: You never took out your spleen on your subordinates. The 14th New Jersey had fought magnificently at Monocacy, and the regiment had paid for it. It would not do to scorn decent men because he was mad at Sheridan.

Monocacy. Truex had led the brigade then. And the fellow had led it well. Then, in August, Truex had lied to him over a matter of horses. It had been a small enough thing in the midst of a war, but Ricketts was old Army. The subordinate who lied to his commander and went unpunished would one day do worse. Despite the man’s battlefield record, Ricketts relieved him.

He hoped he would not regret the action this day.

Monocacy, Monocacy. Poor Wallace, the man of the hour, had gone unrewarded, barely allowed to cling to his Baltimore post, while Ricketts had come in for praise beyond all deserving, in his own opinion. He had tried to speak up for Wallace, to do the man justice, only to find that the politics of the Army, once the arbiters turned against a man, remained unforgiving.

His old wounds ached, both of the flesh and of the spirit.

Ricketts turned his horse from the New Jersey line just as another surge of artillery fire probed his position. Oh, yes, the damned Rebs were waiting for them now.

Bill Emerson trotted beside him, yapping about the effectiveness of the breechloaders his old regiment, the 151st New York, had been issued. They were out on the skirmish line now, popping away.

“Arm the whole brigade like that, and you’d see something,” Emerson assured him.

“Well, it won’t happen today. Christ. There’s Wright again.” Ricketts spurred his horse.

His corps commander rode at a canter behind Ricketts’ second line. With a full complement of aides and all flags flying.

What now?

“Shall I come along, sir?” Emerson asked.

“Stay with your brigade,” Ricketts called over his shoulder. “Get your boys moving the instant you hear that bugle.”

He knew his men would go forward, but Ricketts was unsure of how much grit they’d show in a crisis. They’d behaved well enough in the minor scraps over the past month, but something had bled out of them on the Monocacy, a spirit that went beyond the casualty count. The officers would need to stay near the front of today’s assault.

As Ricketts closed on Wright and his coterie, Warren Keifer, his other brigade commander, rode toward the corps commander, too. As ambitious as he was brave, Keifer had a fondness for the company of his superiors. An Ohioan with political connections, Keifer had defied the doctors to return to the war after his serious wounding in the Wilderness. Now the colonel rode with one arm in a sling and a star on his mind.

Well, let him win his promotion, Ricketts told himself. If he can hold his half-wrecked brigade together.

Amid a flurry of salutes, Horatio Wright asked, “Everything ready, Jim?”

“We’ve been ready,” Ricketts replied. Demonstratively, he drew out his pocket watch. “Going on three hours.”

Wright nodded. “Order’s bound to come down any time now. Where will my courier find you?”

“Up by those guns.”

“Good.”

“We ought to be in Winchester by now.”

“Well, we’re not,” Wright said.

“Any word on Early’s movements?”

Wright shrugged. “I expect they’ll be reinforcing. Nothing to be done.”

For the third time in a matter of minutes, Ricketts held his tongue. Nothing to be done, indeed. Was Wright as blind as Sheridan?

No. But Wright had not risen to corps command through incautious speech or public displays of temper.

Ever so briefly, after praise spread for his stand on the Monocacy, Ricketts had flirted with the notion that he might be granted a corps command himself. His disillusionment had required no more than a look in the mirror as he shaved one morning. Every corps commander he knew had a pleasing appearance that he, drab and growing paunchy, would never possess.

He still marveled that he had somehow married not one, but two, true beauties. And both of them as good-hearted as Saint Clare.

In quick succession, two Reb shells exploded just to the rear of the party on horseback. Close enough to make every officer flinch.

“I suppose we’ve made ourselves a bit conspicuous,” Wright declared.

Yes, Ricketts thought, and thanks for calling further attention to my division’s position. He only hoped his soldiers wouldn’t break. He didn’t want to face the shame of that. Oh, they’d fight, they’d fight. But for how long?

It would come down to the dwindling number of veterans. They had to carry the new men and the shirkers, to drag them toward the Confederates. If the veterans quit …

He had to hit the Johnnies hard and fast, to avoid any faltering.

“All right, then,” Wright added. “I’ll leave you to your task. Give them the devil, Jim.”

“What about Russell’s division? Can I count on him behind me?”

Reining in his mount at another shell burst, Wright said, “I can’t move Russell without Sheridan’s consent.” He offered a smile in lieu of soldiers’ flesh. “Your boys can do this, Jim. Russell won’t be needed.” The corps commander’s horse would not be steadied, but Wright managed a nod toward Keifer’s sling. “Don’t show yourself too openly, Colonel Keifer. Johnnies see that sling, they’ll think we’re scraping the bottom of the barrel.”

And Wright, with his flags and paladins, went off, bracketed by shells. As Union batteries replied, smoke drifted down the lines of waiting men.

The waiting was terrible for them, Ricketts knew. Long delays made cowards of good men.

“This makes no sense,” Keifer told him.

“Damn it, Warren … I know that much.” Despite the mildness of the day, Ricketts found himself sweating. “Go back to your men. Stay ready.”

“I’ve been ready since nine o’clock,” Keifer said. “Longer, for that matter.”

For a fourth time, Ricketts held his tongue. He simply rode away, back to an eminence affording what passed for a view of this wretched terrain. The battery occupying the ridge kept up a perfunctory fire. The old artilleryman in him wanted to dismount and give the crews a lesson in gunnery.

He let his own staff and colors catch up, then got down to empty his bladder. Before he could get to the business, though, a courier burst from the trees, lashing his horse.

Without waiting for his mount to still, the rider shouted, “General Ricketts, you’re to advance at once!”

Removing his fingers from his trouser buttons, Ricketts remounted, loins complaining. It was turning into one thoroughly wretched day.

“On whose authority?” It was important, even now, to do things properly.

“General Wright’s, sir. By order of General Sheridan.”

Satisfied, Ricketts called, “Bugler, to me!” He drew out his watch to mark the time: It was precisely eleven forty.

Horn shining on his hip, the bugler brought his horse abreast of Ricketts.

“Sound the advance.”