New Mexico—More than a decade spent studying cougars reveals the many trials and tribulations of adolescent males as they venture out and attempt to establish territories of their own.

The doe behaved oddly. She stopped foraging and cautiously walked toward a small thicket of junipers. At about forty meters, she stopped and stretched her neck forward, as if straining to see or smell more clearly. Still appearing unsure, she began to circumnavigate the thicket. When her circuit was almost completed, a young puma broke from the cover. He trotted fifteen meters away from the deer, stopped, turned, and returned to the thicket. Thirty seconds later, the puma reappeared and bolted upslope to a lone juniper a stone’s throw from his initial hiding place. Although the young cat did not use characteristic stealth, the doe’s gaze remained fixed on the thicket. She finally lost interest and began feeding. After a quiet hour, I realized the doe and her comrades—a loose group of does, fawns, and one fork-antlered buck—were working their way toward me. Since I did not want to become part of this interaction, I cautiously moved down the draw and off Antelope Hill. No matter. Despite these efforts, my careful movements were more distracting than those of a flustered puma; I was acknowledged by quickly raised heads and frozen stares. To my relief, I proved even less impressive than the cat—the deer resumed feeding. I fixed my binoculars on the lone juniper. If the deer had detected me, surely so had the puma. I smiled when I saw him. This time he used all available cover to his advantage and returned to his original hiding place. His tawny coat blended well with the sandy slopes, but I caught the flash of a yellow ear tag and the black collar around his neck. I knew I would have to return to this place, just to see what Kidd, as I called him, thought was so special about those two little juniper trees.

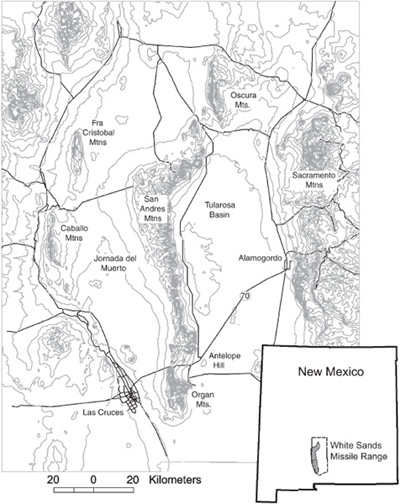

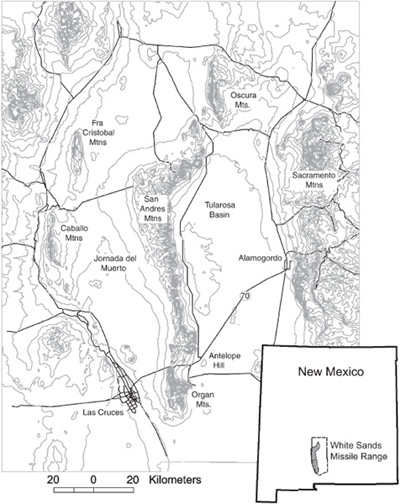

We first caught Kidd in the summer of 1989. Tracks indicated a female and her two cubs were using Black Mountain and traveling the desert draws that led up its south side, including Bonney Spring Canyon. Black Mountain is at the southern end of the San Andres Mountains, located in south-central New Mexico. This long, narrow range stretches seventy miles from south to north, rising up slowly from the creosote flats on the west and dropping dramatically to the desert floor—a mix of Chihuahua desert, gypsum sands, and ancient lava flows—to the east. Although the mountains may appear barren from a distance, the view is deceiving. Perennial springs bubble up through limestone rock and form pools along stretches of shadowed canyons, helping to sustain a rich assemblage of plant and animal life. The tallest peaks reach high enough to break the desert’s grip, supporting healthy groves of piñon, oak, and even ponderosa pine. Although the creation of White Sands Missile Range in the 1940s restricted subsequent human access and impacts on the land, the mountains are rich in human history. During our everyday activities we were reminded of its past—the pictographs, pottery shards, and grinding holes made by ancient peoples; the rock battlements where Chief Victorio and his band of Apaches once took refuge from the U.S. Cavalry; the crumbling walls of a stone cabin where it’s rumored Billy the Kidd once hid; the abandoned homes of homesteaders, including one of lawman Pat Garrett, along with the corrals and pens used to house their goats, sheep, and cattle; and the mine tailings and shafts from an era of frenzied mineral extraction. Now this place, with its relative isolation, limited human access, restrictions on domestic stock, and protected populations of pumas and their prey, had become an ideal location for a puma study.

That summer day, our team was nearing the end of the fourth year of a ten-year study of puma ecology and behavior; Kidd would be our sixty-fourth puma capture. As we approached, we saw a cat that was scared, defiant, and hot. A leg-hold snare held tight to his right forefoot. At six months and twenty kilograms, Kidd was still very dependent on his mother, Two-Catch (female #60), and would be for another seven months. Using a jab stick, we gave Kidd a dose of immobilizing drug. Once he was tractable, we removed the snare, recorded his vitals, and fitted him with an expandable radio collar. As he recovered from the drug, Kidd greedily lapped up water from my cupped hand.

Radio collars provide information on puma behavior and movements that cannot be gathered any other way. The only reason I got a glimpse of Kidd that day on Antelope Hill was that the radio-telemetry signal from his collar told me to look for him there. By radio-collaring pumas as cubs, we are able to determine who survives, who dies and from what, when they become independent from their mothers, and how they behave after independence, including their dispersal paths and distances. Such information can be vital to the successful management and conservation of the species.

The right environmental conditions, a mother’s skill, the cub’s good sense, and a healthy dose of good luck all play a role in a cub’s survival to independence. Although newly independent pumas of both sexes undergo many survival challenges, this story focuses on young males. Newly independent male pumas have a strong urge to travel. Whether aggressive, territorial adult males instigate dispersal or it is more deeply programmed in the cat’s genetics, these felid teenagers typically travel over one hundred kilometers from their birth site before establishing a territory of their own. Two of the longest documented dispersal distances were by males that left their natal areas in central Wyoming and the Black Hills of South Dakota and died in central Colorado and Oklahoma, distances of 480 and 960 kilometers, respectively. Such long dispersal movements by males (females that disperse typically move less than half the distance of males, and some females remain near where they were born) suggest it may be a mechanism to minimize breeding between closely related individuals.

That’s the big picture. Individually, young males have many choices to make and challenges to meet. Two days after seeing Kidd on Antelope Hill, I returned to the site. Kidd was not there, but I did find out what was so special under those two juniper trees—the remains of an old buck and Kidd’s first documented mule deer kill since independence from Two-Catch. Although independent, Kidd had not yet made any long-distance dispersal moves. His kill was at the south edge of his natal range, just south of the highway that connects Las Cruces with the headquarters of White Sands Missile Range, Holoman Air Force Base, and Alamogordo. We found that it often took males a little time before they dispersed, and sometimes they made several attempts (i.e., they would leave their natal area only to return days or weeks later) before they fully committed themselves. Kidd may have needed the prodding from a territorial male to finally make that move. Unfortunately, the male he faced gave no quarter. I was radio-tracking pumas from the air the day I picked up a worrisome double beat from Kidd’s transmitter. I radioed Ken Logan (our field research leader and also my husband) with the news and met him at the site after landing. Male #88, a recent immigrant weighing sixty kilograms, had apparently discovered one of Kidd’s deer kills. At fourteen and a half months and forty-two kilograms (even with a belly full of deer meat), Kidd was no match for #88. We found him lying twenty meters from the deer cache, puma hair in his claws and deadly bite marks to his head.

Most male pumas that survive to independence also survive long enough to begin their dispersal journey. But the path to a new home and a coveted territory is not an easy one. During the window of time we studied the San Andres pumas, larger male pumas killed more of the tagged dispersers as they ventured from their natal homes. Competition between male pumas for space and, more importantly, for the chance to breed with females is probably the impetus for the sometimes deadly fights between males. Such aggressive tactics have probably worked well for the species overall, allowing bigger, stronger, more experienced males to maintain territories where their offspring can safely grow to independence. But deadly fights are not the only danger young males face. Because of their inexperience, and possibly because they are more likely to take chances—it’s a teenager thing—young pumas sometimes get into trouble with people or do things we deem undesirable. For example, after dispersing south within the San Andres Mountains, M23 began to settle into an area that supported some of the few remaining desert bighorn sheep on the mountain. He managed to kill three before a decision was made to move him to central New Mexico, far from desert sheep country. Another disperser (#92) traveled over one hundred kilometers northeast to private ranch-land where he was killed by the landowner for killing calves.

Probably because much of southern New Mexico has a sparse human population, none of our dispersing pumas had direct conflicts with people. But given the distances that these cats typically travel, it is not hard to understand why, in more populated areas, young cats—frequently footloose, naïve males—are sometimes found wandering through a residential area or up on someone’s back porch, testing the palatability of the resident cocker spaniel. In general, the dispersing pumas we studied tended to follow the north-south axis of the San Andres Mountains, enjoying the security it offered for as long as possible.

However, dispersers sometimes made marathon movements across the wide desert basins. It appeared as if they were simply trying to get to other mountain ranges they spied in the distance. Although it may not be easy to trek through arid flatlands sparsely populated with anything a puma would find desirable to eat, imagine instead a puma trying to disperse through landscapes characterized by human development—perhaps along the Front Range of Colorado, from the Sandia Mountains east of Albuquerque, or through the Peninsular Ranges of southern California.

In 2025, eleven western states (Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming) will support about twenty-five million more people than they did in 1999. This population surge will undoubtedly create more challenges for dispersing pumas as more of their habitat becomes altered and fragmented. Although male dispersal is natural and beneficial to puma populations, it sometimes proves difficult and, on rare occasions, it fails to take place at all. Often this is correlated with human-caused alterations to the landscape.

In a study population in southern California, all male progeny attempted dispersal, but whenever they approached the wild-land-urban interface, they stopped—at least for a while. One even returned to establish a territory adjacent to his natal area. The biologist studying that population concluded that unless habitat connectivity was maintained to allow pumas to move freely between habitat patches in the region, the puma population there would probably go extinct. In Florida, extensive agricultural and urban development has isolated the puma population and essentially prohibited most males from freely dispersing.

We even began to see glimpses of this problem in our study population, with the widening of the highway between the San Andres Mountains and the Organ Mountains to the south. Prior to the widening, adults and dispersers occasionally, and safely, crossed the highway. Kidd was among them. After the widening, we documented only two crossings, and both cats were killed. Dispersal is healthy for puma populations, allowing for the influx of new genetic material and repopulation of areas that have experienced extirpation or high puma mortality. Where human impacts affect puma movements, puma subpopulations will become less resilient.

In the ten years we studied pumas in the San Andres Mountains, we captured and tagged 163 pumas while they were still spotted, blue-eyed, nursing cubs. Of those, about 100 pumas made it to independence. The transition from independence to adulthood was tougher on the males, since about 44 percent of males, compared to only about 22 percent of females, did not make it. We recaptured any male that remained within the San Andres Mountains and survived into adulthood. However, we were unable to track very many of the males that ventured beyond the San Andres Mountains because either they were not radio-collared, they slipped their collars, or we lost track of them.

I was anxious to observe a success in the form of a male puma that dispersed outside the study area, established a territory, and produced offspring of his own. I thought I was going to witness it with Houdini, one of three cubs born to Female #4 in the summer of 1986. We marked his sisters at four weeks of age—but Houdini managed to evade capture (hence his name) until his first birthday. He stayed with his mother for two more months. When she met up with the resident male to breed again, Houdini was on his own. On the same hill where, over two years later, Kidd made his very first deer kill, Houdini found himself in a standoff with one of his mother’s suitors—Male #1. Considering another young disperser had tried to evade #1’s fury by climbing a utility pole (where he was immediately electrocuted), I was a little surprised—and admittedly elated—that Houdini survived the encounter. With experience comes wisdom, so I was not surprised when, days later, Houdini was on the move, traveling northwest across the creosote flats of the Jornada del Muerto (literally, “journey of death”) to the Caballo and Fra Cristobal Mountains east of Elephant Butte Reservoir.

Weekly I would make the drive to the Alamogordo airport, strap antennas to the wing struts of a Cessna 182, and fly with pilot Bob Pavelka to locate pumas from the air. That’s why I knew where to look for Houdini. Two days after one of these flights, I found myself negotiating the rutted dirt roads west of the reservoir, searching for tangible evidence of the cat. I stopped the truck by a shallow draw and poked along up it. There they were—the large, rounded tracks of a puma walking at a steady pace. I bent down and touched a track, and then gazed in the direction they headed—toward the dark silhouette of the Black Range. Houdini had safely crossed the Rio Grande and Interstate 25 and was heading to his new home.

This was the closest I would ever again be to Houdini. Over the next year I tracked him weekly from the air. Then we got the call—a hunter’s dogs had cornered Houdini and he had been killed. At only thirty months of age, it was possible Houdini had sired a litter, but just as likely not.

It’s hard to read success in the face of a frightened, narrow-faced, wide-eyed cat that is all ears. Number 82 (who would later earn the name of Lupe) had already left his mother and begun his southward dispersal move through the San Andres when we snared and collared him. At sixteen months and forty-three kilograms he was already bigger than many adult females, but he had the lanky look, narrow face, and flawless, tawny coat of a cat that had a lot of growing to do and experience to gain. Knowing the gauntlet of territorial males, busy highways, housing developments, hunters, and temptations (in the form of domestic livestock) Lupe would face once he left the San Andres Mountains, I was not optimistic he would live long. Maybe Lupe felt the same, since he soon turned around and went back home. Four months later he tried again, beginning one of the longest journeys of any of our tagged cubs. Lupe went south again, but this time he followed the mountain chain all the way to its conclusion, the Franklin Mountains overlooking the sprawling town of El Paso. For the next eighteen days, I could not find him. Then, with expanded aerial searches, I was able to pick up a familiar beat. Possibly thwarted by what he encountered, Lupe shunned the city, turned east, and crossed seventy-four kilometers of stark desert to a momentary safe haven in the Sacramento Mountains. His journey continued over the next three months, until something told him he had found what he was looking for—a new home in the Guadalupe Mountains.

Almost every week, Bob and I made the aerial journey to these mountains, searching for Lupe’s signal. I still remember some of those trips—the contrast of white and wet gypsum sand on the wind-formed hills of White Sands National Monument; the rows of cotton-ball clouds below us, stretching to the horizon; the drone of the engine and hiss of the receiver as I strained to hear his signal; the drop in engine power and downward circling as we pinpointed Lupe’s location in the rocky crags and juniper-covered hillsides.

A little over two years later, the batteries in Lupe’s transmitter finally gave out; our connection was gone. But this time I was confident I’d witnessed success. Lupe was over four years old and a prime adult puma. Just maybe, one day, one of his descendants will make the journey back to the San Andres Mountains and his genes will again mix with those of the desert cats that dwelled there.

As a scientist I must remain objective; however, our intimate knowledge of these pumas’ lives could not help but produce respect, admiration, and a pang of loss when an animal died. But the individual loss is buffered by the belief that the species will endure. I must also admit a bias, a deep desire for pumas to exist, to evolve, and to continue to affect the evolutionary direction of the ungulate species they depend on for survival. My experience with pumas in New Mexico leaves me hopeful; my further experience studying these cats in the rapidly changing landscapes of California makes me recognize the difficulties that lie ahead. Even on the Uncompahgre Plateau of Colorado, where I sometimes assist with monitoring collared cats, tagging cubs, and investigating the places where pumas have been, I can see the changes. In the summer of 2004, Ken and I stood on Horsefly Canyon’s west rim and got tantalizing glimpses of puma #6 and his very vocal mate. Just above them, jutting from the opposite rim, perched a new two-story home.

Pumas are resilient and adaptable, but it will take a caring, engaged citizenship to ensure the puma’s future. Part of our success will be dependent on a better understanding of puma behavior and not simply on our ability, or lack thereof, to precisely estimate puma numbers. Observing and analyzing the behavior of animals helps to inform us about the life history strategies that help them to survive, reproduce, and, ultimately, persist.