Utah—An expedition on the Green River leads this biologist and explorer through the heart of red rock cougar country, revealing the ecological subtleties of canyons and plateaus that the golden cats roam.

The tawny cougar seems born of rock, this rock in this canyon.… One easily imagines a cougar on a ledge above the river… a creature indistinguishable from the canyon, too distant to reveal the story of summer on the river, reflected back to us in its green-gold eyes.

—ELLEN MELOY, RAVEN’S EXILE

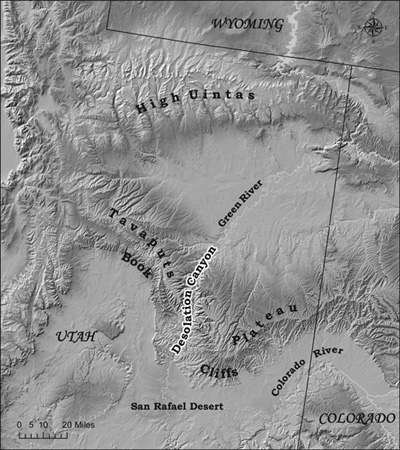

Rising abruptly from the floor of the San Rafael Desert are the Book Cliffs, named for the dark red striations horizontally running through the formation. When the sun is at low angles, the cliffs convey an image of a giant book resting on its side. From the south, the lower cliffs form an impenetrable wall of rock resembling a fortress capped with sandstone turrets.

These cliffs are but one of several prominent layers within a larger geologic structure called the Tavaputs Plateau. Collectively, these layers form an arc between the Wasatch Mountains of Utah and the Grand Mesa of Colorado, acting as a biogeographic corridor—an uninterrupted expanse of montane and subalpine plant communities ecologically connecting the Great Basin to the Rocky Mountains. The corridor helps to maintain demographic and genetic connectivity between populations of mesic-adapted species in an otherwise contiguous desert. Resembling a two-legged table, it is not a mountain range per se but more of a tilted escarpment; the skeletal remains of a wetter time now oddly juxtaposed on a dry continent. Small gullies, hardly noticeable at first, quickly turn into major canyons, and flat plains narrow to ridges that dead-end four thousand feet above the desert floor. It is this pattern of beginning at the top and working down that characterizes sandstone country. Here, erosion is constant but, like the shape of the land, tends to be punctuated rather than continuous. Erosion is to the landscape as peer review is to the scientific method: a process that results in longevity not through an eruptive force but by whittling away the alternatives that do not hold up to scrutiny or time.

In between the starry-eyed town of Sedona and the 13,000-foot crest of the Uinta Mountains lies the Colorado Plateau—one of the most rugged and least accessible landscapes left in western north america. The tavaputs are the central feature within this province. These sedimentary strata formed when the entire region was beneath an ancient sea. Over millions of years the basin was squeezed upward along massive fault lines, leaving it high and dry. Now the bottom is on top. It is these rocks and their distinct way of breaking down that give the area its character and moniker, Castle Country. No other part of the region so aptly exemplifies this description or its connotation.

AN OASIS IN THE DESERT

Cleaving the tavaputs into two unequal parts is the Green River—the only passage through the Book Cliffs. The Utes referred to the river as Seedskeedee-agee, meaning “prairie hen.” the Spaniards, perhaps finding the native term cumbersome, named it Rio de los Ciboles (Bison River), and later changed it to el Rio verde. The latter name resulted in the anglicized Green River, abbreviated even further in the vernacular to simply “the Green.”

Independent of semantics, the river is the lifeblood of the desert. From its glacier-derived headwaters in Wyoming’s Wind River Range, it is a meandering oasis in an otherwise parched landscape. The river winds down through the red rocks to its confluence with the Colorado River, where, like a bride, it gives up its name to the equally impressive but not necessarily larger stream.

Water is a precious resource in the West and, paradoxically, is often most abundant in the driest of places. In 1964 the Green was impounded at Flaming Gorge, impacting a host of rare aquatic and riparian organisms that evolved under the warm, flashy flow of a shallow desert stream. The dam has reduced the frequency and intensity of spring flood events, and along with it the volume of sediment moving through the system. In turn, many ecological processes have been altered, from plant communities to spawning habitat for native fish.

The course of the Green is not just remote in spatial terms but temporally as well. In his journals, George Bradley, a crew member on Powell’s first voyage down the Green, lamented the inhospitability of the area: “a terrible gale of hot, dry wind swept our camp and roared through the cañon mingling its sound with the hollow roar of the cataract making music fit for the infernal regions. We needed only a few flashes of lightning to meet Milton’s most vivid conceptions of Hell.” the Powell expedition named the canyon Desolation.

I have come to this place with a crew conducting research on the Green River fish community. Native species are declining in the face of society’s unyielding one-two punch: radically altered habitat conditions compounded by competition with exotic game fish. Ameliorating the combined effects of direct killing and habitat loss is a common theme in modern practice of conservation biology. Along those lines, my interest in the canyon was its function as a refuge for mountain lions. I had been involved with research examining the spatial patterns of cougar mortality and wanted to explore small pockets of remote habitat where cougars were not likely to encounter people. The conclusions of my work were based on the premise that hunting can have notable effects on cougar society. Extrapolating, perhaps localities with little or no hunting pressure might act as reservoir populations capable of supplementing outlying areas where cougars were more susceptible to negative encounters with society. Coming here I had three primary objectives: (1) determine if the area was indeed suitable habitat; (2) search for evidence of cougar presence within the canyon corridor; and (3) if cougars were present, assess the reasons for the lack of hunting pressure in the area. Desolation Canyon lies at the broken heart of a watershed covering more than one thousand square miles, which, according to crude measures, provides suitable habitat with little human intrusion.

The fact that cougars are still as widespread as they are is a testament to their tenacity. More importantly, it is also a direct result of their preference for rugged terrain. This animal exemplifies all the qualities of a species vulnerable to extinction—large territories, low densities, and conservative reproductive rates. Increasing road densities make the cats’ habitat more accessible, and the demand for hunting opportunities continues to rise. Further hindering conservation efforts, this creature—often called “ghost cat”—is a virtual apparition and the ability to census it in a reliable and economical fashion remains elusive. In a shrinking world, their population status is in question.

Life flourishes along the river. Once on the water, solitude reigns. Moving water and birdsong are the only sounds. Most of the larger plants in this system, such as willow, maple, and cottonwood, occur in a thin band along the banks of the river. Away from the water the vegetation quickly transitions to sagebrush and other drought-adapted species. Where there is enough soil and moisture, shrubland gives way to piñon-juniper forest, and on the highest ridges Douglas fir and ponderosa pine can be seen spilling down the north-facing slopes.

As the boat drifts downstream it becomes apparent that the plant community is in a state of transition. An invader from the Mediterranean called tamarisk—or salt cedar—is out-competing other water-loving species that grow along the shoreline. Tamarisk was introduced to the Southwest as a shelter-belt tree during the nineteenth century and has now spread through most of the major watercourses in the region. Functionally, it reduces the inherent variability in the environment by stabilizing the banks, narrowing the channel, and sequestering groundwater. Ecologically, it tends to support lower biodiversity than the flood-adapted willows it is replacing. This tree also affects the dynamics of beach erosion and sandbar development, which, in conjunction with the dam, has led to declines in spawning habitat for the endangered Colorado pike minnow. Yet other species, such as the willow flycatcher, have adapted well to the replacement of native willows with tamarisk. Either way, over much of the Desert Southwest this plant now forms the dominant habitat type for species that depend on stream-side forests.

PAINTED PONIES

The first night’s camp was located on a broad sandbar on an inside meander. The moist sand was evidence that the water level was dropping quickly and that only a week or so prior this beach had been submerged. All day the weather had been threatening, but as darkness approached, it became clear that what had appeared to be an afternoon thunderstorm was settling in for the evening. In preparation, we staked down our tents and lashed the bowlines of the boats to a dead tree stranded at the high-water mark. With the waning of the day, the wind picked up, blowing sand across the beach in swirling patterns, helping me appreciate the sentiments of Powell’s crew. The bank opposite our camp was a steep concave wall of sandstone capped by spires and hoodoos that silhouetted the southern horizon. As the storm intensified, lightning appeared sporadically as a broad arc above the ridge, illuminating the entire canyon for a split second at a time. Each thunderclap sounded like a cannon echoing through an amphitheater. It was following the first squall that i heard a foreign sound. It was the neighing of horses coming from the tributary behind camp. I could feel their hoof beats reverberate through the sand as they sought safe haven from the electricity.

Nevada and Wyoming have more wild horses than any other states, but wild horses are also common in Utah. Mustangs are found throughout the Book Cliffs, where they make up part of a larger population that spills into Colorado. Although Equus evolved in north america, all members of the genus became extinct here approximately eight thousand years ago. Today, horses found in the new World are feral animals of eurasian origin. Accidentally or otherwise, they were reintroduced to Mexico by Spanish explorers during the 1600s. These herds expanded northward on their own, and over time their numbers were subsidized by animals that escaped from prospectors and pilgrims settling the western territories. Equus caballus is now firmly established across much of the western hemisphere. Native grasses and shrubs in this arid land have evolved for several millennia without grazing by horses. This repatriation may have come with some as yet poorly understood ecological implications for desert plant communities.

There are places in the deserts of western north america where wild horses have been identified as a staple grain for mountain lions. Indeed, one study conducted on Montgomery Pass in California’s White Mountains found that foals constituted a significant proportion of the cougar diet during summer and fall. Predation was most pronounced in the higher elevations where steep terrain and piñon-juniper forests provided sufficient cover. Cougars preyed on the annual cohort into autumn, when either seasonal movements made their acquisition more difficult or the foals had matured to a size and savvy where they were no longer vulnerable. It is not clear whether lions would be there without the horses, or if the horses are relieving some of the predation pressure that might otherwise be directed at native ungulates such as deer and bighorn sheep. Nevertheless, under those conditions the native predator was able to incorporate the now exotic herbivore into its dietary repertoire.

The most fundamental component of habitat for any creature is the abundance and diversity of food resources. Regarding the mountain lion, habitat has one other primary component: the cover that enables it to acquire the food. The horse is a grazer, meaning that its diet is made up primarily of grasses and forbs, whereas deer are browsers, as their typical diet comprises shrubs. There is some evidence indicating that grazers may actually improve habitat for browsers, as they tend to preferentially impact plants that compete with shrubs for moisture and soil nutrients. In many shrub-steppe ecosystems, minimal dietary overlap may allow the coexistence of these large herbivores. In this country, horses are relegated to a landscape that is very amenable to the way a cat conducts its business. Broken terrain forces animals to use predictable routes to the water’s edge, where dense vegetation provides ample stalking cover. The presence of horses may benefit the cougar both directly as a food resource and indirectly as a modifier of habitat for its preferred prey species, mule deer.

RAGGED EDGES

My duty as a member of this fleet is to pilot the supply boat. It is a large inflatable raft piled high with camping gear, scientific equipment, and other sundry “necessities.” the canyon is nearly one hundred miles long, and numerous rapids punctuate an otherwise gentle current. The vegetation lining the banks is raucous with bird activity. At regular intervals great blue herons flush from backwater eddies where they hunt for small fish. The conditions for tracking here are beyond compare and I have plenty of time to drift into back bays and explore beaches for animal sign. It is August and the peak runoff has long passed with lingering patches of snow relegated to a few north-facing cirques in the higher reaches of the watershed. The farmers on either end of the canyon are drawing water from the river to irrigate their crops. We watch the water level drop with each passing day, as evidenced by the fine layer of silt left on the shore. It is this muddy canvas that provides a time stamp of the passing of creatures ranging in size from caterpillars to feral cattle. It is amazing how many species make a living within this narrow band of riparian woodland. On one beach i find sign of a black bear sow traveling with two cubs. As the trip proceeds i find evidence of horses at nearly every cottonwood spring or tributary.

Driftwood is everywhere. From its headwaters in northern Colorado to its confluence with the Green in Dinosaur national Park, the Yampa River is the largest tributary to the Green and a relic of the old regime. Combined with pulses from summer thunderstorms, the Yampa is responsible for a large amount of the untamed energy pulsing through Desolation Canyon. As a result, logs thirty feet long and a foot in diameter are stacked on rocks twelve feet above the current water level. Logjams and debris piles create habitat for insects, birds, and small mammals and building materials for beavers, while slowing the flow of sediment through the system. The Yampa remains a truly wild river, but its days as such may be numbered—four of the most rapidly growing states in the United States are in the Desert Southwest, where water is a commodity often spoken of in terms similar to those of oil and gold.

In the desert, water is the first and last limiting resource. In mountainous country, abrupt elevation gradients force hot air to rise and cool, thereby creating thunderstorms during the summer months. The plateau is made of sandstone, and water readily dissolves the bonds holding sand particles together. Moving water incises more rapidly in the vertical plane than in the horizontal, giving the land an inordinately steep character. The stairstep fashion in which sandstone erodes is evident on every scale, from the silt layers deposited on the beach, to the monolithic blocks that form the rim and widen the canyon at infrequent but noteworthy intervals. Flash flooding sends house-sized boulders cascading into the river, creating rock gardens and turbulence. Irregular gradients in the river contribute to the formation of rapids. Each is preceded and followed by languid water where sediment accumulates, creating backwaters and beaches that support localized gallery forests. The importance of these oases for wildlife is far greater than the total area they occupy. Cottonwood springs not only harbor resident animals but also act as transitional habitat for birds migrating between Mexico and the far northern latitudes.

NAGACHI AND TUKU—THE SHEEP AND THE BIG CAT

Three days into the trip i found what i was looking for. Numerous islands dot the river. Some are nothing more than ephemeral sandbars, whereas others have been stabilized by tamarisk and are now longer-term features of the river. It was on one of these islands that I detected conclusive evidence of cougar presence in the canyon.

One of my fellow crew members decided to explore the lee side of a moderate-sized island. Although these boats do not draw much water, they do require some, and this left our mate high and dry. I paddled in on the downstream side of the island where I could hike up the shore to help him out of the shallows. The water had recently receded and the mud in the channel was knee deep. Along its harder edge was an improvised trail. There in the drying mud was the track of a tom lion. Unmistakable in size and by the three-lobed heel, he had walked upstream along this backwater bank and vanished into the thickets. It was hard to tell how old the tracks were—several days at least. The blades of grass that had been pushed down under the weight of his foot had regained their posture. Additionally, small cracks were developing in the mud around the edges, indicating that the sun had baked the medium in which the event had been recorded. Serendipity has always played a significant yet unpredictable role not only in love but in scientific endeavors as well.

Potential prey species for the cougar were present, but elusive. It was in the deepest part of the canyon that I sighted several bighorn sheep on the cliffs above a major tributary. Seven sheep in all—four ewes, two lambs, and a yearling ewe. They scrambled over the cliffs on the east side of the river. The Green did not appear to be much of a barrier to movement for wildlife, but it was interesting that most of the animals I had seen were on tribal lands, on the eastern side of the river.

The bighorn sheep is a creature with a tumultuous history—a quality unlikely to change in the future. Bighorn numbers dropped precipitously following the introduction of domestic sheep to western rangelands in the mid-nineteenth century. Diseases for which the native sheep had no immunity combined with market hunting left them extirpated from most of their historic range. Today, the bighorn represents a tenuous management success story. Symbolically reintroduced to many of its former haunts, it hangs on to a precarious future. Conservative reproductive rates, fire suppression, and competition with deer impede widespread recolonization. The halt in its decline is due largely to aggressive management driven by the desires and financial backing of trophy hunters eager for a chance to collect a specimen of this wilderness icon. Therein lies the rub. The bighorn inhabits some of the roughest and most remote country left in the West. Along with the golden eagle, the mountain lion is one of the few predators equally well-adapted to this terrain. Cougars have a proclivity for killing wild sheep, much to the chagrin of sportsmen’s organizations. In less productive habitats, the generalist nature of this feline comes out, and its fondness for deer wanes in favor of whatever is readily available. The presence of bighorn indicates that there is yet another species that may in part sustain Big Whiskers.

It is quite clear why there are no cougars taken out of this drainage. Irrespective of habitat, there are few roads to gain access; the only way in or out is by boat, which during spring runoff is not a venture for the faint of heart and during winter all but the rapids are frozen. The land has only three prominent angles: flat, vertical, and the odd forty-five-degree slope that connects the two. Without trails or roads, even a mule would be hard-pressed to negotiate the steep, crumbling complexity that makes up this barren landscape.

The presence of humans and the importance of hunting are readily apparent in the rock art we find among the cottonwood springs. Petroglyphs are replete with references to animals. One panel illustrates a human figure pulling back a bow with an arrow pointed at something resembling a wild bighorn. Hunting has taken place here for a long time. It is quite possible that less hunting takes place in this canyon now than at any other time in the last millennia.

The descendents of these early hunters are still here, although relegated to precisely surveyed reservations on the eastern half of the Tavaputs Plateau. In the odd place where a trail or dirt road does reach the canyon bottom, there are prominent signs reminding travelers that from the river eastward are Ute tribal lands. The western side of the canyon is under the guidance of the Bureau of Land Management. Regardless of ownership, the Book Cliffs are part of a larger region rich in fossil fuels and, coincidentally, are not protected by wilderness designation. Portions of the canyon corridor have been eyed by energy companies eager to take advantage of the favorable political climate. Exploration is preceded by road development, which inevitably leads to greater access and subsequently the exploitation of all natural resources. When the stakes get high enough, even eden becomes negotiable.

AUTUM N COLORS

In the wild nothing is sacred and change is the only constant. Humans do everything they can to maintain the status quo—whatever that may be. Such is every species. All organisms attempt to modify their immediate environment in such a way as to enhance the highs and minimize the lows. The quaking aspen is a common member of subalpine plant communities across north america. It is called mid-successional because it makes its living during the times following a major perturbation, such as an avalanche or fire. The things aspens cannot tolerate are aridity, shade, and an undisturbed environment. These factors, alone or in concert, presage the decline of aspens, and thus their absence from climax communities. Aspens also attempt to minimize variation in certain life-history requirements. Although they need frequent fires to kill off competitors, they also need predictable sources of water.

At the apex of Desolation Canyon, where its depth rivals that of the Grand, aspens cling on in the highest north-facing alcoves. During cooler and wetter times, the trees were much more widely distributed. As the climate warmed and dried, clones at lower elevations and on southerly aspects perished. Over time, aspens “retreated” to the refugia of the highest and wettest recesses of the mountain. The interesting thing about this phenomenon is that organisms do not necessarily move to better spots, so much as they die out at the edges of their range where changes in the environment are most apparent. Significantly, modern society has sought to eliminate wildfire, whereas pre-colonial inhabitants deliberately set fires because early successional plant communities supported more wild game. Historically, aspens were a direct beneficiary of early forest management and a lightning-rich climate.

In the Book Cliffs, the desiccating influence of the desert has pushed the tree with the fluttering leaves high into the last strongholds of its domain. In its wake come the drought-tolerant species, such as piñon pine, juniper, and, where fires have become scarce, Douglas fir—none of which can support the same abundance of wildlife as their predecessor. In the face of a drier climate and interference from man, the climax community arises and the competition continues between a different set of players, where again fire and water will arbitrate the outcome. Balance is only the average of extremes and exists, if at all, only for fleeting moments.

ALLEE AND EDGE EFFECTS: A SCIENTIFIC ASIDE

As once-contiguous species distributions develop holes, connectivity—or the unimpeded flow of individuals—decays. The result is an array of subpopulations of various sizes. Breaks can occur where mortality is too high or where habitat quality degrades and cannot support resident animals. Each subpopulation exhibits its own dynamics based on size and factors associated with reproduction and survival. Collectively, these subpopulations are referred to as a metapopulation, within which the relatively larger constituent populations become increasingly important for persistence. Some of the lateral connections and demographic redundancies built into the social structure of the species act to dampen the risk of extinction. For example, transients are young, sexually mature animals that wander within the population, waiting for the death of a resident and the availability of a territory. When this cohort disappears, reproduction may decline. This has been documented in southern California, where a lion population surrounded by the sprawl of Los Angeles lost its last resident male. Reproduction ceased for a year before a transient male finally finessed the gauntlet and entered the population.

In regions where cougar presence is becoming temporally spotty, allee effects can occur. Named for W. C. allee, a pioneering population ecologist during the 1930s and 1940s, this phenomenon occurs when animals become so scarce that breeding declines because potential mates are scattered too widely. This is the primary impediment to cougar recolonization of suitable habitat east of the Mississippi River. Transients dispersing eastward from the Rockies are present but are spread out over such a wide area that reproduction is untenable. Thus, Allee effects act to accelerate declines in a low-density population.

The edge effect is the geographic equivalent of a surface to volume ratio. A given subpopulation may be surrounded by unsuitable habitat, such that most home ranges abut or overlap some agent of mortality or impediment to movement. This in turn reduces or eliminates immigration, making population persistence wholly dependent upon internal reproduction. The more insidious effect is that of inbreeding and genetic isolation, which invariably follow in the wake of segregation. Such is the case of the Florida panther, and one of the primary reasons that population exhibits such a high conservation profile.

Because humans have exerted such a strong influence on ecological processes—via the introduction of exotic species, abbreviating successional pathways, and exploitation—the larger and presumably more demographically stable populations are likely to occur in areas less accessible to direct human interference. Current genetic evidence indicates that this may have already taken place with cougars on a large scale. The Pleistocene epoch was marked by extinctions or severe range contractions of a wide array of north American fauna. In conjunction with the fossil record, genetic studies suggest that cougars also may have been substantially reduced in distribution during that time. However, populations in the tropics—where the effects of climate change were less pronounced—buffered the species from extinction and acted as a source for the recolonization of north america following glacial retreat.

A CAT THE COLOR OF STONE

Even in a land far from civilization, biotic communities are anything but pristine. In the desert, species both loved and reviled by society interact. Some of the success stories of modern wildlife management are evident; counterbalancing these successes, however, are a host of aliens established through both negligence and premeditation. Fish in the river, plants along the banks, and feral livestock grazing the hills—all in an ecosystem altered by a now static river flow. The counterpoints to this consortium of ecological wild cards are the indigenous species that persist. Species with carnivorous tendencies have caused much consternation among human societies for occupying a niche with a high degree of overlap with our own. The large predators have been labeled as pests and therefore persecuted to the point that the wilder, more remote portions of their ranges represent their last chances for survival. The black bear and the mountain lion straddle a fine line—adaptable to human presence but vulnerable in the long run. The cougar is often invoked as a symbol of wilderness; yet, it is such only because that is how we perceive it in our common mythos and, more importantly, what we make it by our own hand. Semi-urban cougar populations illustrate that this species does not require pristine wilderness to survive. Nevertheless, the social hysteria and destruction of habitat surrounding non-wilderness cougars clearly demonstrate the motives and means by which humans relegate their demons to the hinterlands.

In wilderness these creatures occur despite the tempest outside. Their once expansive and continuous ranges have been fractured, not forcing them into remote areas but making their welcome anywhere else so lukewarm that it is only in the wild areas that they persist. Where the desert gnaws away at the garden, a new community is forming. One in which vestiges of the old world either make do or make way for competitors spilling over the battlements. This begs the question, is the cougar a member of the old guard vainly holding together a crumbling ecosystem or the ultimate opportunist thriving on an ecosystem in flux? the erosion of one species’ distribution may coincide with the invasion and spread of a new one. New members filling niches of extinct natives or, like the cougar, old ones maintaining a role they have always played—but interacting with a different cast of characters. New ecosystems arise.

The lion of the mountains still roams this sandstone citadel. On the far end of the canyon the cliffs diminish in stature and the river widens as it flows into the San Rafael. An old tire lies stranded on a sandbar where the Price River drains into the Green. In the evening, the pungent scent of burning sage and piñon pine rises up through the air. The day wanes as I listen to the breeze blowing through the cottonwood leaves overlaid on the rhythm of moving water. The low-angle sun illuminates colors within the rocks that are all but invisible during the heat of the day. The west-facing wall of the canyon is lit up in a bright red, as though a light were coming from within the stone. A great blue heron soars above the river on an invisible current of air in time with the turbulence of the water. And, somewhere, a whisker twitches.