THE CULTURES OF Australia’s indigenous peoples, Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, are rich in story. Together with song, dance and art, stories were a principal means of preserving and transmitting cultural knowledge from generation to generation. Much indigenous story is related to secret and sacred ritual and excluded from general circulation. But there is also an extensive repertoire of legends and stories that may be told freely. The very small selection of such stories given here demonstrates the powerful connections between the land and all the living things upon it that is the foundation of indigenous belief.

Wirreenun the rainmaker

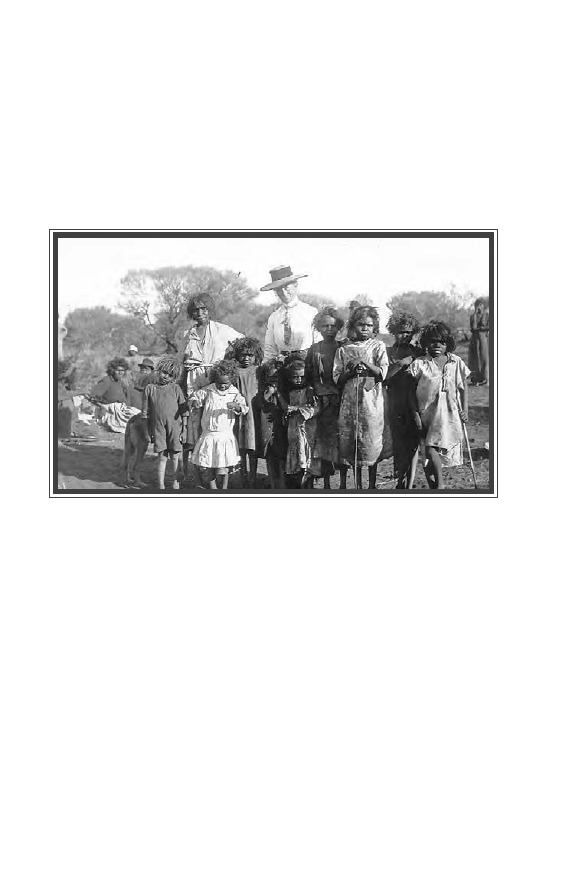

Katherine Langloh-Parker (1856–1940) was the wife of a settler near Angledool, New South Wales. She developed a close relationship with the Noongahburrah, a branch of the Yularoi people. Her knowledge of their customs, beliefs and language helped her compile a unique record of the indigenous traditions of the Narran River region, even if filtered through the perceptions of an outsider and through various translations and retellings.

Wirreenun (meaning a priest or doctor) is a rainmaker who uses his magical abilities to help his people, despite the lapse of their belief in his powers. In this story, Wirreenun is also a name.

The country was stricken with a drought. The rivers were all dry except the deepest holes in them. The grass was dead, and even the trees were dying. The bark dardurr (humpy) of the blacks were all fallen to the ground and lay there rotting, so long was it since they had been used, for only in wet weather did they use the bark dardurr; at other times they used only whatdooral, or bough shades.

The young men of the Noongahburrah murmured among themselves, at first secretly, at last openly, saying: ‘Did not our fathers always say that the wirreenun could make, as we wanted it, the rain to fall? Yet look at our country—the grass blown away, no doonburr seed to grind, the kangaroo are dying, and the emu, the duck, and the swan have flown to far countries. We shall have no food soon; then shall we die, and the Noongahburrah be no more seen on the Narran. Then why, if he is able, does not Wirreenun make rain?’

Soon these murmurs reached the ears of the old Wirreenun. He said nothing, but the young fellows noticed that for two or three days in succession he went to the waterhole in the creek and placed in it a willgoo willgoo—a long stick, ornamented at the top with white cockatoo feathers—and beside the stick he placed two big gubberah, that is, two big, clear pebbles which at other times he always secreted about him, in the folds of his waywah, or in the band or net on his head.

Especially was he careful to hide these stones from the women.

At the end of the third day Wirreenun said to the young men: ‘Go you, take your comeboos and cut bark sufficient to make dardurr for all the tribe.’

The young men did as they were bade. When they had the bark cut and brought in, Wirreenun said: ‘Go you now and raise with ant-bed a high place, and put thereon logs and wood for a fire, build the ant-bed about a foot from the ground. Then put you a floor of ant-bed a foot high wherever you are going to build a dardurr.’

And they did what he told them. When the dardurr were finished, having high floors of ant-bed and water-tight roofs of bark, Wirreenun commanded the whole camp to come with him to the waterhole; men, women, and children, all were to come. They all followed him down to the creek, to the waterhole where he had placed the willgoo willgoo and gubberah. Wirreenun jumped into the water and bade the tribe follow him, which they did. There in the water they all splashed and played about.

After a little time, Wirreenun went up first behind one black fellow and then behind another, until at length he had been round them all, and taken from the back of each one’s head lumps of charcoal. When he went up to each he appeared to suck the back or top of their heads, and to draw out lumps of charcoal, which, as he sucked them out, he spat into the water. When he had gone the round of all, he went out of the water. But just as he got out, a young man caught him up in his arms and threw him back into the water.

This happened several times, until Wirreenun was shivering. That was the signal for all to leave the creek. Wirreenun sent all the young people into a big bough shed, and bade them all go to sleep. He and two old men and two old women stayed outside. They loaded themselves with all their belongings piled up on their backs, dayoorl (grinding) stones and all, as if ready for a flitting. These old people walked impatiently around the bough shed as if waiting a signal to start somewhere. Soon a big black cloud appeared on the horizon, first a single cloud, which, however, was soon followed by others rising all round. They rose quickly until they all met just overhead, forming a big black mass of clouds. As soon as this big, heavy, rain-laden looking cloud was stationary overhead, the old people went into the bough shed and bade the young people wake up and come out and look at the sky.

When they were all roused Wirreenun told them to lose no time, but to gather together all their possessions and hasten to gain the shelter of the bark dardurr. Scarcely were they all in the dardurrs and their spears well hidden when there sounded a terrific clap of thunder, which was quickly followed by a regular cannonade, lightning flashes shooting across the sky, followed by instantaneous claps of deafening thunder. A sudden flash of lightning, which lit a pathway from heaven to earth, was followed by such a terrific clash that the blacks thought their very camps were struck. But it was a tree a little distance off. The blacks huddled together in their dardurrs, frightened to move, the children crying with fear, and the dogs crouching towards their owners.

‘We shall be killed,’ shrieked the women. The men said nothing but looked as frightened.

Only Wirreenun was fearless. ‘I will go out,’ he said, ‘and stop the storm from hurting us. The lightning shall come no nearer.’

So out in front of the dardurrs strode Wirreenun, and naked he stood there facing the storm, singing aloud, as the thunder roared and the lightning flashed, the chant which was to keep it away from the camp.

‘Gurreemooray, mooray, durreemooray, mooray, mooray,’ &c.

Soon came a lull in the cannonade, a slight breeze stirred the trees for a few moments, then an oppressive silence, and then the rain in real earnest began, and settled down to a steady downpour, which lasted for some days.

When the old people had been patrolling the bough shed as the clouds rose overhead, Wirreenun had gone to the waterhole and taken out the willgoo willgoo and the stones, for he saw by the cloud that their work was done.

When the rain was over and the country all green again, the blacks had a great corroboree and sang of the skill of Wirreenun, rainmaker to the Noongahburrah.

Wirreenun sat calm and heedless of their praise, as he had been of their murmurs. But he determined to show them that his powers were great, so he summoned the rainmaker of a neighbouring tribe, and after some consultation with him, he ordered the tribes to go to the Googoorewon, (a place of trees) which was then a dry plain with solemn, gaunt trees all round it, which had once been blackfellows.

When they were all camped round the edges of this plain, Wirreenun and his fellow rainmaker made a great rain to fall just over the plain and fill it with water.

When the plain was changed into a lake, Wirreenun said to the young men of his tribe: ‘Now take your nets and fish.’

‘What good?’ said they. ‘The lake is filled from the rain, not the flood water of rivers, filled but yesterday, how then shall there be fish?’

‘Go,’ said Wirreenun. ‘Go as I bid you; fish. If your nets catch nothing then shall Wirreenun speak no more to the men of his tribe, he will seek only honey and yams with the women.’

More to please the man who had changed their country from a desert to a hunter’s paradise, they did as he bade them, took their nets and went into the lake. And the first time they drew their nets, they were heavy with goodoo, murree, tucki, and bunmillah. And so many did they catch that all the tribes, and their dogs, had plenty.

Then the elders of the camp said now that there was plenty everywhere, they would have a borah that the boys should be made young men. On one of the ridges away from the camp, that the women should not know, they would prepare a ground.

And so was the big borah (ceremonial gathering) of the Googoorewon held, the borah which was famous as following on the triumph of Wirreenun the rainmaker.

Mau and Matang

Australia’s northernmost extreme is the small island of Boigu, just six kilometres off the coast of Papua New Guinea. The six clans of the island began when a man named Kiba and his brothers settled there. Christian missionaries came to Boigu in 1871, an event commemorated today in the annual ‘Coming of the Light’ ceremony, which blends Boigu mythology with elements of Christian belief.

This important Boigu tale of impending doom, revenge and warrior honour highlights the importance of reciprocal relationships—even those of revenge and blood—and the high regard in which warrior skills were held by all the people of Torres Strait and beyond.

Long ago there were two warrior brothers of Boigu, Mau and Matang. Mau was the elder brother. They fought for the love of fighting and very often for no reason.

One day they received a message from their friend Mau of Arudaru, which is on the Papuan mainland just across from Boigu. Mau bade them come quickly for yams and taro, which would otherwise be eaten by pigs.

Mau and Matang made ready to go to Arudaru.

Their sister wove the sails for their canoes. At mid-afternoon, just as she had completed them, she noticed a big stain of blood on one mat. She hurried to her brothers to tell them about it and so try to prevent them from setting out on their voyage.

Mau and Matang would not heed the warning sign, and they set off with their wives and children. They reached Daudai and spent the first night at Kudin. During the night Mau’s canoe drifted away. The brothers sent the crew to search for it, and they came upon it at Zunal, the sandbank of markai (spirits of the dead).

As they drew close, they saw the ghost of Mau appear in front of the canoe. In its hand was a dugong spear decorated with cassowary feathers. The ghost went through the motions of spearing a dugong, then placed the spear in the canoe and vanished.

Next they saw Matang’s ghost pick up the spear from the canoe, just as Mau’s had done. It too made as if to spear a dugong. Then it replaced the spear in the canoe and faded from sight.

On reaching the canoe, the crew members found the spear in it.

On their return to Kudin they told Mau and Matang what had happened. The brothers refused also to heed this warning. They ordered the party to set out for Arudaru, which they reached after a day’s walk.

The head man of Arudaru, whose name also was Mau, greeted them, with his own people and many others, gave them food, and said that he would give them the yams and taro the following day. With that, the Boigu people slept.

In the morning they woke to a deserted village. Only Mau of Arudaru remained. He gave them breakfast and then presented Mau and Matang with a small bunch of green bananas. It was a declaration of war.

Despite the friendship between Mau of Arudaru and the brothers Mau and Matang, the brothers had lightly killed kinsmen and friends of his, and his first duty as Mau of Arudaru was to avenge them. The invitation to come across for yams and taro had been part of a considered plan.

For days past, fighting men from the neighbouring villages had been gathering at Arudaru. There had been endless talking until the whole plan had ripened. With rage in their hearts, Mau and Matang herded their party together and set out on the return journey.

Mau of Arudaru had hidden his fighting men in two rows in the long grass so as to form two rows of unseen men. He allowed the brothers to lead their people back until they were halfway through the lines of fighting men. Then he gave the signal to attack.

The Boigu people were trapped. The women and children and the crew members fled. Mau bade his brother break the first spear thrown at him. He himself with his bow warded off the first spear that was hurled at him, splitting the end and throwing it backward between his legs, thus giving himself good luck in battle.

Matang warded off the first spear received by him, but did not break it as Mau had commanded.

Before long Matang was struck in the ankle by an arrow with a poisoned tip. ‘I have been bitten by a snake,’ he cried, and fell dead.

Mau continued to fight and kept backing towards his brother’s body until he stood astride it. He fought until nearly all his assailants lay dead. The rest would have fled, but Mau signalled to them to put an end to him, so that he might join his brother. And this they did.

Mau and Matang did not have their heads cut off as would have been done were they ordinary men. Their courage and skill in battle were honoured by their opponents. They sat the brothers against two trees. They tied their bodies to the tree trunks, facing them south towards Boigu. On their heads they placed the warrior’s headdress of black cassowary feathers and eagles’ wings, so that when the wind blew from the south the eagles’ wings were fanned backward and when it dropped, they fell forward.

Ungulla Robunbun

The anthropologist Baldwin Spencer (1860–1929) documented the complex oral traditions about ancestral beings and totemic relationships among the Kakadu people, publishing these in 1914 as The Native Tribes of the Northern Territory of Australia. The female entity in this story from Spencer’s book creates birds, insects and human beings, giving male and female their physical characteristics. She is also the bringer of language. Pundamunga and Maramma, mentioned at the end of the story, are descended from the one great female ancestor of the Kakadu, Imberombera. Imberombera travelled all over the region, leaving her spirit children wherever she went and eventually sending them forth to take the different languages to the countries of Pundamunga and Maramma. Ungalla’s naming of Pundamunga and Maramma’s children confirms that this is the country of these two beings and their descendants. Once again, the story highlights the spiritual connections between country, ancestors, totems and language that are the basis of indigenous culture. Spencer recounts the following tale, including a reference to the tale being told to him.

A woman named Ungulla Robunbun came from a place called Palientoi, which lies between two rivers that are now known as the McKinlay and the Mary. She spoke the language of the Noenmil people and had many children. She started off to walk to Kraigpan, a place at the head of the Wildman Creek. Some of her children she carried on her shoulders, others on her hips, and one or two of them walked. At Kraigpan she left one boy and one girl and told them to speak the Quiratari (or Quiradari) language. Then she walked on to Koarnbo Creek, near the salt water at Murungaraiyu, where she left a boy and a girl and told them to speak Koarnbut. Travelling on to Kupalu, she left the Koarnbut language behind her and crossed over what is now called the East Alligator River, to its west side. She came on to Nimbaku and left a boy and a girl there and told them to speak the Wijirk language. From here she journeyed on across the plains stretching between the Alligator rivers to Koreingen, the place to which Imberombera had previously sent out two individuals named Pundamunga and Maramma. Ungulla Robunbun saw them and said to her children, ‘There are blackfellows here; they are talking Kakadu; that is very good talk; this is Kakadu country that we are now in.’

Ungulla went on until she came near enough for them to hear her speaking. She said, ‘I am Kakadu like you; I will belong to this country; you and I will talk the same language.’ Ungulla then told them to come close up, which they did, and then she saw that the young woman was quite naked. Ungulla herself was completely clothed in sheets of ranken, or paper bark, and she took one off, folded it up, and showed the lubra how to make an apron such as the Kakadu women always wear now. She told the lubra that she did not wish to see her going about naked. Then they all sat down. Ungulla said, ‘Are you a lubra?’ and she replied, ‘Yes, I am ungordiwa.’ Then Ungulla said, ‘I have seen Koreingen a long way off; I am going there. Where is your camp?’ The Kakadu woman said, ‘I shall go back to my camp if you go to Munganillida.’ Ungulla then rose and walked on with her children. On the road some of them began to cry, and she said, ‘Bialilla waji kobali, many children are crying; ameina waji kobali, why are many children crying?’ She was angry and killed two of them, a boy and a girl, and left them behind. Going on, she came near to Koreingung and saw a number of men and women in camp and made her own camp some little distance from theirs. She then walked on to Koreingung and said, ‘Here is a blackfellows’ camp; I will make mine here also.’

She set to work to make a shelter, saying ‘Kunjerogabi ngoinbu kobonji, I build a grass shelter; mornia balgi, there is a big mob of mosquitoes.’ As yet the natives had not seen Ungulla or her children. There were plenty of fires in the natives’ camps but no mosquitoes. They did not have any of these before Ungulla came, bringing them with her. She went into her shelter with her children and slept. After a time she came out again and then the other natives caught sight of her. Some of the younger Numulakirri determined to go to her camp. When she saw them coming she went into her kobonji and armed herself with a strong stick. She was Markogo, that is, elder sister, to the men, and, as they came up, she shouted out from her bush wurley, saying, ‘What are you all coming for? You are my illaberri (younger brothers). I am kumali to you.’

They said nothing but came on with their hands behind their backs. As soon as they were close to the entrance to her shelter she suddenly jumped up, scattering the grass and boughs in all directions. She yelled loudly and, with her great stick, hit them all on their private parts. She was so powerful that she killed them all and their bodies tumbled into the waterhole close by. Then she went to the camp where the women and children had remained behind and drove them ahead of her into the water. The bones of all these natives are still there in the form of stones with which also their spirit parts are associated. When all was over the woman stood in her camp. First of all she pulled out her kumara (vagina) and threw it away, saying, ‘This belongs to the lubras.’ Then she threw her breasts away and a wairbi, or woman’s fighting stick, saying that they all belonged to the lubras. From her dilly bag she took a paliarti, or flat spear-thrower, and a light reed spear, called kunjolio, and, throwing them away, shouted out, ‘These are for the men.’

She then took a sharp-pointed blade of grass called karani, caught a mosquito (mornia) and fixed it on to his head (reri), so that it could ‘bite’ and said, ‘Your name is mornia.’ She also gave him instructions, saying, ‘Yapo mapolio, jirongadda mitjerijoro, go to the plains, close to the mangroves; manungel jereini jauo, eat men’s blood; kumanga kaio mornia, (in) the bush no mosquitoes.’ That is why mosquitoes are always so abundant amongst the mangroves. When she had done this Ungalla gathered her remaining children together and, with them, went into the waterhole.

There were a great many natives, and, after they were dead, their skins became transformed into different kinds of birds. Some of them changed into small owls, called irre-idill, which catch fish. When they hear the bird calling out at night they say ‘dodo’, which means wait, or, later on; ‘tomorrow morning we will put a net in and catch some fish for you’. Others turned into kurra-liji-liji, a bird that keeps a look out to see if any strange natives are about. If a man wants to find out if any strangers are coming, he says to the bird, ‘Umbordera jereini einji? Are men coming to-day?’ If they are, the bird answers, ‘Pitjit, pitjit.’ Others changed into jidikera-jidikera, or willy wagtails, which keep a look out for buffaloes and crocodiles. Others, again, changed into dark-coloured kites, called daigonora, which keep a look out to see if any hostile natives are coming up to ‘growl’. A man will say to one of these daigonora, if he sees it in a tree, ‘Breikul jereini jeri?’ that is, ‘Far away, are there men coming to growl?’ If the bird replies to him he knows that they are coming, but if it makes no sound, then he knows there are no strangers about. Others changed into moaka, or crows, that show natives where geese are to be found; others into tidji-tidji, a little bird that shows them where the sugar-bags may be secured; others into mundoro, a bird that warns them when natives are coming up to steal a lubra. Some, again, changed into murara, the ‘mopoke’, which warns them if enemies are coming up in strong numbers. They ask the bird, and if it answers with a loud ‘mopoke’ they know that there are none about and that they have no need to be anxious, but if it answers with a low call, then they know that hostile natives are somewhere in the neighbourhood, and a man will remain on watch all night. Some of the women changed into laughing jackasses.

All these birds are supposed to understand what the blackfellows say, though they cannot themselves speak. While the men were explaining matters to us they spoke to two or three wagtails that came close up and twittered. The men said that the birds wanted to know what we were talking about, but they told them that they must go away and not listen, which they did.

Before finally going into the waterhole, Ungulla called out the names of the natives to whom she said the country belonged. They were all the children of Pundamunga and Maramma.

Ooldea Water

The colourful and enigmatic Daisy Bates (1863–1951) spent many years living with Aboriginal people in southwestern Australia. She claimed a special relationship with them that gave her unique access to indigenous traditions and insights into their significance. While these claims and many of her interpretations of the anthropological evidence she gathered have been strongly challenged, the stories she collected and preserved are of great value as records of traditions that have since fragmented or been completely lost.

In her book The Passing of the Aborigines Daisy Bates dramatically introduces the story of how the small marsupial Karrbiji brought water to Ooldea, in South Australia. The explorer Earnest Giles in 1875 was one of the first Europeans to discover this permanent water source, over 800 kilometres west of Port Augusta, on the eastern edge of the Nullarbor Plain. Bates lived at Ooldea from 1919 to 1934 and gave this description of the place:

Nothing more than one of the many depressions in the never-ending sandhills that run waveringly from the Bight for nearly a thousand miles, Ooldea Water is one of Nature’s miracles in barren Central Australia. No white man coming to this place would ever guess that that dreary hollow with the sand blowing across it was an unfailing fountain, yet a mere scratch and the magic waters welled in sight. Even in the cruellest droughts, it had never failed. Here the tribes gathered in their hundreds for initiation and other ceremonies.

In 1917 the Transcontinental Railway opened and the small settlement became a watering point for the railway line. By 1926 the water had been drained off in a process well described by Bates:

In the building of the transcontinental line, the water of Ooldea passed out of its own people’s hands forever. Pipelines and pumping plants reduced it at the rate of 10,000 gallons a day for locomotives. The natives were forbidden the soak, and permitted to obtain their water only from taps at the siding. In a few years the engineering plant apparently perforated the blue clay bed, twenty feet below surface. Ooldea, already an orphan water, was a thing of the past.

Despite these events, Ooldea retained its special significance for local Aborigines, though access to the area was restricted during the 1950s in response to the atomic testing at Maralinga. By 1988, Ooldea was again Aboriginal land thanks to the Maralinga Tjarutja Land Rights Act.

This is the legend of Ooldea Water.

A long, long time ago in dhoogoor times, Karrbiji, a little marsupial, came from the west carrying a skin bag of water on his back, and as he travelled east and east there was no water anywhere, and Karrbiji said, ‘I will put water in the ground so that the men can have good water always.’

He came to a shallow place like a dried lake. He went into the middle of it, and was just going to empty his water bag when he heard someone whistling. Presently he saw Ngabbula, the spike-backed lizard, coming threateningly towards him, whistling.

As he watched Ngabbula coming along, Karrbiji was very frightened, and he said, ‘I can only leave a little water here. I shall call this place Yooldil-Beena—the swamp where I stood to pour out the water,’ and he tried to hide the water from Ngabbula by covering it with sand, but Ngabbula came along quickly and Karrbiji took up his skin bag and ran and ran because Ngabbula would take all his water from him.

By and by he had run quite away from Ngabbula, and soon he came to a deep sandy hollow among high hills, and he said, ‘This is a good place, I can hide all the water here, and Ngabbula won’t be able to find it. He can’t smell water.’

Karrbiji went down into the hollow and emptied all the water out of his bag into the sand. He covered up the water so that it could not be seen, and he said, ‘This is Yooldil Gabbi, and I shall sit beside this water and watch my friends finding it and drinking it.’ Karrbiji was feeling very glad that he had put the water in such a safe place.

All at once, he again heard loud whistling and he looked and saw Ngabbula coming along towards him. Karrbiji was very frightened of Ngabbula, and he quickly picked up his empty skin bag and ran away; but fast as he ran, Ngabbula ran faster.

Now, Giniga, the native cat, and Kallaia, the emu, were great friends of Karrbiji, and they had watched him putting the water under the sand where they could easily scratch for it and drink cool nice water always, and they said, ‘We must not let Ngabbula kill our friend’, and when Ngabbula chased Karrbiji, Kallaia and Giniga chased Ngabbula, and Ngabbula threw his spears at Giniga and made white spots all over Giniga where the spears had hit him. Giniga hit Ngabbula on the head with his club, and now all ngabbulas’ heads are flat, because of the great hit that Giniga had given Ngabbula.

Then they ran on again and Ngabbula began to get frightened and he stopped chasing Karrbiji, but Kallaia and Giniga said, ‘We must kill Ngabbula, and so stop him from killing Karrbiji,’ and a long, long way north they came up to Ngabbula, and Kallaia, the emu, speared him, and he died.

Then they went to Karrbiji’s place, and Kallaia, Giniga and Karrbiji made a corroboree, and Beera, the moon, played with them, and by and by he took them up into the sky where they are now kattang-ga (‘heads’, stars).

Karrbiji sat down beside his northern water. When men came to drink of his water, Karrbiji made them his friends, and they said, ‘Karrbiji is our Dreamtime totem,’ and all the men who lived beside that water were Karrbiji totem men. They made a stone emblem of Karrbiji and they put it in hiding near the water, and no woman has ever walked near the place where the stone emblem sits down.

Kallaia, the emu, ‘sat down’ beside Yooldil Water, and when the first men came there they saw Kallaia scraping the sand for the water, and they said ‘Kallaia shall be our totem. This is his water, but he has shown us how to get it.’ Giniga, the native cat, went between the two great waters, Karrbiji’s Water and Kallaia’s Water, and was always the friend of both. Ngabbula was killed north of Yooldil Gabbi, but he also had his water, and men came there and made him their totem, but Kallaia totem men always fought with Ngabbula totem men and killed them and ate them.

Karrbiji, after his work was done, went north, and ‘sat down’ among the Mardudharra Wong-ga (wonga-ga-speech, talk), not far from the Arrunda, beside his friends Giniga, the native cat, and Kallaia, the emu. And he made plenty of water come to the Mardudharra men, and by and by the men said, ‘Karrbiji has brought his good water to us all. We will be brothers of Karrbiji.’

The woolgrum

This story is from the Weelman people of Australia’s far southwest, now known broadly as Nyungar. It was told to Ethel Hassell, the wife of an early settler in the area during the 1870s. The woolgrum is half woman, half frog. This story, in one variation or another, was widely told. The possibility of winning a non-human wife is widespread in global tale tradition.

Far, far away in the west toward the setting sun there are three big rivers. The waters are fresh and flow down to the sea. Long, long ago, a jannock (spirit) lived between these rivers who had neither companions nor wives. He was very lonesome in this region but had to remain there for a certain time. To help overcome his loneliness he tamed all the animals in the region and they became fast friends with him. In the evening they used to sit around his fire. The chudic (wildcat) sat with the coomal (opossum), they told him stories of what was going on in the forest and on the plains.

In times of flood the rivers used to expand over a great expanse of territory, making many marshes, and, since the water was fresh, these became the breeding grounds for all kinds of gilgie (crayfish), fish and frogs [and] the jannock became friends with them too. There was one kind of frog, however, that he had difficulty in taming. This was plomp, the bullfrog. He coaxed the plomp to visit him and finally was able to persuade them to sleep under his cloak with him. He also tamed the youan, or bobtailed iguana. The youan made love to the plomp and this became very annoying to the jannock. He told the plomp that the youan made friends only that they might eat the young plomp. The plomp were grateful to him for this warning and showed their appreciation by surrounding his hut every night and singing him to sleep.

This kept up for some time, but finally it was time for the jannock to return to the other jannock. Just before he left, he breathed on the frogs and told them that in time they would be like himself.

The jannock had no business to say this, however, for he had not the power to cause them to change into beings like himself. The result was that every now and again the plomp brought forth a creature which is called a woolgrum. It is always half woman and half frog and never like a man. The woolgrum, being of jannock blood, were able also to make themselves invisible.

Now, when a man is an outcast from his tribe, no woman will live with him, even though the ostracism is not due to any fault of his own. As a last recourse to find a wife, he must travel towards the setting sun until he comes to the three great rivers which roll widely down to the sea through the broad marshes and between banks covered with thick-growing scrub. When he reaches this land he will hear the frogs croaking and on still nights he will hear the woolgrum calling. He will not be able to see them, however, because of their jannock blood, except on starlight nights in the winter when there is no moon. At that time the woolgrum come on shore and build a hut and a fire to warm themselves. On those occasions, men can sometimes see the figures of women camped by the fire. If they go too near to the fire or make a rush and try to grab the women, however, they find nothing but bushes, and the woolgrum disappear, never again to return to that camp. They make camp in another region where they may be seen again under the same conditions, but it is impossible to catch them in such a bold manner.

The only way by which a man can get a woolgrum for a wife is by following these directions. He must camp alone near the big marshy flats and live only on fish and gilgie. He must not tell anyone where he has gone or for what purpose. He must camp there until the marshes begin to dry up, at which time he must search for the youan and catch a female in the act of giving birth to her young. Just as the sun sets, but before it is dark, he must throw the newly born youan on the fire and watch until it bursts. As it burst, he must turn to the river marshes, and then he will see the woolgrum. As soon as he sees them he must seize the remains of the infant youan, throw it at the woolgrum, and run as fast as he can to the river.

If a portion of the youan touches a woolgrum, the lower or frog part disappears and a naked woman stands in the marsh. If he acts quickly he can catch her for his wife, but if he does not move hastily she will sink into the water and float down toward the sea. If this happens, there is nothing he can do to save her. He must commence his operations all over again in another region, for the woolgrum will never return to that part of the river. He will also have to wait until the next winter, when the woolgrum come to camp on the shore again.

However, should he be successful in catching the woman, he must take her to his camp and roll her up in his cloak and keep her warm by the fire all that night. The next day he can take her as his wife but must hurry away from the locality and remain constantly by her side until the moon is again in the same quarter. By that time she will have lost her power to make herself invisible and, once this is gone, she will never leave him no matter what his faults may be. She will bear him many children and they will be stronger and much more clever than any of the men or women of his tribe. They soon become bad men and women, however, and can never have any children, though the men take many wives and the women many husbands. Thus a man who gets a woolgrum for a wife knows that, although he may have many children, he will never have any grandchildren and his race will disappear completely. No jannock can harm his children because of their jannock blood, and they are always able to tell when the jannock are about.

The woolgrum herself is very beautiful, but her children are decidedly ugly, with big heads and wide mouths. They are capable of travelling very quickly, however, especially in the river beds and over marshy land, and they have a most highly developed sense of hearing. No native woman likes to think that her son would like to seek a woolgrum for a wife, for this is done only as a last recourse. No man likes to be told that his mother was a woolgrum, for that reflects on his father’s character and implies that he will never have any children to fight for him in his old age.

The woolgrum are said not to belong to either moiety; hence, whether a man is a Nunnich or a Wording, he can take as a wife any woolgrum he can catch without questioning her relationship.