During Prohibition, D. G. Yuengling & Son survived by making “near beer” and diversifying into other areas, including dairy products.

BEER IS A simple, fermented, alcoholic drink made from water, barley (a cereal grain), hops (the bitter, pungently aromatic flower of the female hop plant), and yeast (a live, one-celled organism). Beyond those four basic components, however, beer is also a beverage that is brewed all over the world, with a complex flavor profile, and which is available in a wide range of colors, flavors, styles, and alcoholic strengths.

Beer has an ancient history – traces of a primitive, fermented drink have been found in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, and it’s likely that early civilizations throughout the world made a beer-like drink. A 6,000-year-old Sumerian tablet discovered in Mesopotamia shows several people using straws to drink from a communal bowl – they look like they are enjoying themselves, so maybe they are sharing a beer – and a 3,900-year-old Sumerian poem honoring Ninkasi, the patron goddess of brewing, purportedly contains an ancient recipe for beer.

The first “beers,” made from spontaneously fermented sugary substances – likely cereal grains – were not very beer-like. The beverage was most likely a sour brew made from whatever was handy and plentiful – honey, berries, fruits, and grains – and accidentally fermented by airborne wild yeast. Hops had not yet been cultivated and were unknown, therefore this primitive beer would have been flavored with herbs and spices. Cultivation and use of hops in beer was a significant development in the history of brewing. Hops impart bitterness and aroma, but also have a preservative effect on beer, inhibiting bacterial growth. Although there is a written record of hop use in beer as early as AD 822 in northern France, the cultivation and widespread use of hops really began sometime around the twelfth or thirteenth century in what is now Germany. Brewers in the Middle Ages also often used herbs and spices in place of hops. You may have been lucky enough to find a “gruit” – a beer brewed with a combination of herbs in place of hops – at your local brewery or brewpub.

A hop farm in Washington State. Most US hops are grown in the Pacific Northwest.

Beer, specifically ale, has been part of the American landscape since the Pilgrims landed – reputedly they had to cut their journey short and land in the New World in the first place because they were in danger of running out of beer! Ale was a staple of everyday American life, brewed in small batches for a household’s own use, or to supply a tavern or inn’s thirsty patrons. Clean water was difficult to come by and drinking it was risky. Ales, which were boiled, were a much safer alternative, and the alcohol in the beverage helped to stave off contaminants and increase its “shelf life.”

Many of the Colonial forefathers, among them George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson, brewed their own beer on their farms and estates (although it’s likely the women and servants did the actual work). Like the ancients, the colonists would have used ingredients that were grown close to home and in abundance – the food supply could not be compromised. These early colonial brews, designed more for sustenance than merriment, were low in alcohol, and brewed with ingredients such as corn, wheat, barley, and molasses. Beer in America experienced a significant change in the mid-nineteenth century when the German immigrants arrived, bringing to their new homeland their contagious exuberance for beer, which was irrevocably enmeshed in their culture. These German tradesman and journeyman brewers brought a wealth of skills and traditions, such as the Reinheitsgebot, also known as the German Purity Law of 1516, which decreed that beer was to be brewed only with water, hops, and barley.

The earliest known photo of the Yuengling brewhouse, about 1855.

Employees of D. G. Yuengling & Son, Inc., about 1873.

In the ensuing years, these new Americans established local and regional breweries, making beers that were reminiscent of their homeland – strong, heavy styles. They didn’t just satisfy the needs of their burgeoning German-American population, however – they also succeeded in introducing their new countrymen to their “national” drink, the lager beer. In a time before refrigeration, lagers were fermented in cool places such as caves. The lower temperatures required a longer fermentation period, resulting in a cleaner, crisper beer.

As the popularity and production of beer, wine, and spirits increased, a staunch anti-alcohol campaign began to take shape across the country. The growing temperance movement, which frowned on intoxicating liquors, to put it mildly, along with anti-immigrant sentiment, moved some states to make early attempts at banning alcoholic libations. Most of these efforts were short-lived until the Volstead Act, or National Prohibition Act, in 1919, and the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which went into effect on January 16, 1920.

Beer wagon at the Yuengling brewery, about 1870.

Prohibition, also known as the “Noble Experiment,” made the manufacturing, sale, and transportation of alcoholic beverages illegal, but not its consumption. Hundreds of the smaller breweries, most of them family-owned, were put out of business, but many of the larger breweries were able to continue and thrive. The names of these German brewers are still recognizable; they have long dominated the national brewing landscape and become synonymous with American beer – Joseph Schlitz, Frederick Pabst, Frederick J. Miller, Adolph Coors, Eberhard Anheuser, and Adolphus Busch.

Yuengling racking cellars, about 1900.

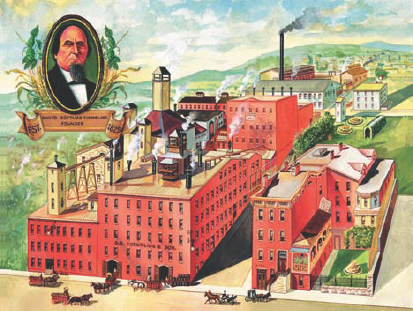

Some of these larger breweries relied on good, old-fashioned ingenuity and diversified, producing other products to stay in business. America’s oldest brewery, D. G. Yuengling & Son, Inc. (established as the Eagle Brewery) in Pottsville, Pennsylvania, is one such Prohibition success story. Forced to shut down its beer production for more than a decade, the brewery survived by making “near beer,” a legal drink because it contained virtually no alcohol, and by building a dairy across the street. The brewery, still family-owned, has operated continuously since 1829.

Illustration of Yuengling Brewery and its founder, David Gottlieb Yuengling.

Despite Prohibition, alcohol was still being produced domestically – albeit illegally – as well as being smuggled into the country. In order to turn a tidy profit, bathtub booze and beer was often watered down. Perhaps due to the influence of these Prohibition and post-Prohibition era beers, Americans seemed to develop a taste for these lighter lagers.

The Twenty-first Amendment ended Prohibition on April 7, 1933, but once closed, the small, local breweries supplying hearty beers were gone for good. After World War II, returning GIs embraced the light-bodied beers and a new trend was born. With few exceptions, it would be decades before the flavorful, full-bodied beers made by smaller breweries were again available in the United States.

Adding to the lack of variety, virtually no foreign beers were imported into the US in the early years after Prohibition, leaving a beer landscape dominated by the large breweries. Benefiting from a lack of competition, the large breweries continued to grow, but there were still some successful regional breweries, such as Yuengling, which provided beer to a localized population.

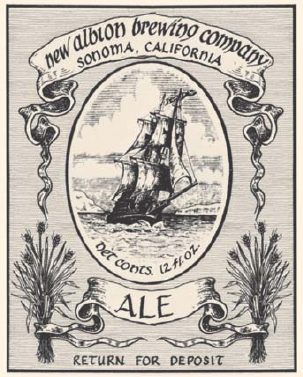

New Albion Brewing Company, which opened in 1977 and closed five years later, is recognized as the first modern American “microbrewery.”

The West Coast is undisputedly the birthplace of the modern craft beer movement. In 1965, Fritz Maytag bought a controlling interest in a failing brewery. His business philosophy – to brew diverse, flavorful beers, some of which were lost styles – was successful and the Anchor Brewery was saved.

While Anchor is regarded as the first “craft” brewery since Prohibition, most consider New Albion Brewery, opened by Jack McAuliffe in Sonoma, California, to be America’s first modern microbrewery. A visionary with a fondness for British ales, McAuliffe built his brewery from scratch and opened in 1977. Unfortunately, McAuliffe was ahead of his time and New Albion closed in 1982.

The brewing industry witnessed another milestone in 1977 when Bert Grant, a native Scotsman, opened Yakima Brewing & Malting Co. in Washington State. This was the first time since Prohibition that an establishment was able to serve its own beer along with food: the first brewpub was born.

Back in the early 1980s, when modern brewing pioneers McAuliffe and Grant were making history, fewer than one hundred breweries were operating in the United States. Today, there are more than 2,500 craft breweries in the US, with many more poised to open in the next few years.

A German-built brewhouse newly installed in an American microbrewery, New Jersey’s Flying Fish Brewing Company. Thanks to the increasing popularity of craft beer, breweries around the country are expanding their facilities.

Today’s breweries come in all shapes and sizes. Beer production is measured by the barrel, a unit of liquid measure equal to 31 gallons. What we casually refer to as a “keg” is technically a half (15½ gallons) or quarter (7¾ gallons) barrel. The smallest craft breweries, often referred to as “nanobreweries,” rely on brewing systems not much bigger than one a home brewer might use. In comparison, the brewing giants produce millions of barrels per year.

Today, the numerous independent craft breweries opening across the country are true to their roots. They are small, cater to a community-based clientele, strive to use local ingredients in their beers, and take pride in naming their breweries and brews after familiar geographical or historical landmarks.

Thanks to President Jimmy Carter, home brewing was legalized on the federal level in 1979, but it wasn’t until 2013 that it was allowed in every state, when Mississippi and Alabama finally legalized home brewing. While home brewers enjoy more freedom than their predecessors, alcohol is highly regulated in the US and even home brewers are bound by federal, state, and local laws. For example, some states require hobbyists to obtain a home-brewing license. Others restrict the amount of beer produced per year to a few hundred gallons. There may also be stipulations that the beer is used only “for personal consumption,” or that it may not leave the premises.

A traditional copper-hooded kettle at The Ship Inn, a brewpub in Milford, New Jersey.

Rather than quell hobbyists’ interest in home brewing, the spate of new brewery openings and the increased availability of local brews in recent years has only served to spur on the home-brewing movement, a commentary on our love affair with craft beer.

A very small nanobrewery system at the Tuckahoe Brewing Co., Oceanview, New Jersey.