![]()

DEVELOPING OUR CONCENTRATION helps us steady our attention. The next skill we’ll develop, mindfulness, helps us to free our attention from burdens we may not even know we’re hauling around.

The first time a meditation teacher encouraged me to practice mindfulness—which entails giving purposeful, nonjudgmental attention to whatever arises in the present moment—I made a discovery. As I focused my attention not only on each breath but also on any thought, emotion, or physical sensation that came up while I was sitting, I began to notice that with each experience, two things were happening. There was the actual experience and then there was what I was adding on to it because of habitual responses that I’d developed over a lifetime.

One of the first places I saw this happening was in my knees. My teacher encouraged his students not to move during our sittings. I, however, always moved; my knees hurt; so did my back. The more I tried to be still, the more I shifted and readjusted. Eventually I realized that I moved not because the pain in my knees or back was really so severe, but because as soon as I felt one little moment of discomfort, I’d start thinking, What’s it going to feel like in ten minutes? In twenty minutes? It’s going to be unbearable. So I’d change positions, motivated not by present discomfort, but by anticipated pain. I was imagining aches multiplied by minutes, hours, years, until I felt them as a burden too impossibly big for anyone to bear. And then I’d spiral into self-judgment: Why did you move? You didn’t have to move. You’re always the first to move.

The disruption to my concentration from moving lasted only thirty seconds, but the disruption from anxiously imagining the future and then unleashing all those rebukes added another ten minutes of mental distress. Until I learned to spot those add-ons—a tendency to judge myself harshly and to spin a permanently miserable future from a temporary sensation—they came between me and my direct experience: This is what knee pain feels like right now, not an hour from now. It’s throbbing, needle-like. Now it’s little spasms, with a still space between them.… Can I handle it for right now? Yes, I can. Only direct experience gives us the crucial information we need to know what is actually happening.

Mindfulness, also called wise attention, helps us see what we’re adding to our experiences, not only during meditation sessions but also elsewhere. These add-ons might take the form of projecting into the future (my neck hurts, so I’ll be miserable forever), foregone conclusions (there’s no point in asking for a raise), rigid concepts (you’re either for me or against me), unexamined habits (you feel tense and reach for a cookie) or associative thinking (you snap at your daughter and then leap to your own childhood problems and then on to deciding you’re just like your mom). I’m not saying we should abolish concepts or associations; that’s not possible, nor is it desirable. There are times when associative thinking leads to creative problem-solving, or works of art. But we want to see clearly what we’re doing as we’re doing it, to be able to distinguish our direct experience from the add-ons, and to know that we can choose whether to heed them or not. Maybe there is no point in asking for a raise, maybe there is. You can’t know until you separate your conditioned assumption—I never get what I ask for—from the unadorned facts of your work situation

A very good place to become familiar with the way mindfulness works is always close by—our own bodies. Investigating physical sensations is one of the best ways for us to learn to be present with whatever is happening in the moment, and to recognize the difference between direct experience and the add-ons we bring to it. Next week we’ll apply the tool of mindfulness to emotions and thoughts.

I once witnessed a particularly good example of add-ons in action when I was teaching a retreat with my colleague Joseph Goldstein. We were sitting drinking tea when a student in some distress came in and said, “I just had this terrible experience.” Joseph asked “What happened?” And the man said, “I was meditating and I felt all this tension in my jaw and I realized what an incredibly uptight person I am, and always have been and I always will be.”

“You mean you felt some tension in your jaw,” Joseph said. And the man said, “Yes. And I’ve never been able to get close to anyone, and I’m going to be alone for the rest of my life.”

“You mean you felt tension in your jaw,” said Joseph. I watched the man continue barreling down this path for some time, all because of a sore jaw, until finally Joseph said to him, “You’re having a painful experience. Why are you adding a horrible self-image to it?”

I’m sure you know how the man with the sore jaw felt. We’ve all had times when we’ve declared ourselves total losers or envisioned a bad end based on a fleeting sensation or thought. A typical trip down that path goes like this: I bend down to tie my shoe, and somehow I pull a muscle in my back. This is the beginning of the end, I think. Now everything will start to go. (Joseph would say, “You mean you hurt your back.”)

This week’s mindfulness exercises—a Body Scan, a Walking Meditation, a Body Sensation Meditation, and three shorter meditations rooted in everyday experiences—will help us feel more comfortable and in tune with our bodies. They’ll deepen our understanding of the way our experiences are constantly changing, and they’ll help us spot our add-ons.

In Week Two, add a fourth day of practice, with a session of at least twenty minutes. Try to integrate both walking and sitting meditations. If you meditate in the evening and you’re feeling either extra restless or drowsy, you may want to do a walking meditation as a way of rebalancing your energy. Or you may simply enjoy getting back into your body if you’ve been sitting at a desk and living in your head all day.

Though some of this week’s meditations begin with our concentrating on the breath, as in Week One, or using the breath as an anchor to which we can return, breathing isn’t always the main focus. Some don’t involve awareness of the breath at all. The breath is one of the many tools for training attention; in this 28-day introductory program, my goal is to give you an overview of many different methods and techniques available to you.

In the Body Sensation Meditation, for example, we’ll use mindfulness to observe the way we automatically cling to pleasant experiences and push away unpleasant ones. It’s natural to perceive everything we think, feel, or take in with our five senses as being pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral. Whether we’re enjoying the sun on our face, hearing an insult, listening to music, smelling our dinner cooking, or feeling a wave of anger, the experience gets sorted into one of these three slots. It’s just what humans do.

When the experience is pleasant, our conditioned tendency is to hang on to it and keep it from leaving. That, however, is impossible. “Nothing endures but change,” said the Greek philosopher Heraclitus. We long for permanence, but everything in the known universe—thoughts, weather, people, galaxies—is transient. That’s a fact, but one we fight. Mindfulness allows us to enjoy pleasant experiences without that extra thing we do, which is to grasp at the pleasure in an attempt to keep it from changing. In fact, we’re often so preoccupied with trying to make a pleasurable experience stay that we’re unable to enjoy it while it lasts.

I remember losing touch with mindfulness when a friend from California who’d never been East planned an autumn visit to New England. Anticipating her arrival, I anxiously worried about whether the resplendent, colorful leaves would stay beautiful for her. It’s got to be this way when she comes, I thought. If the leaves fall and they’re all brown and shriveled, what kind of an inaugural autumn visit will that be for her? As it turned out, she wasn’t able to come after all. When I heard that, I thought, Well, I guess now I can just let nature take its course. Obviously, it’s ludicrous to try to keep leaves from falling from the trees. And I’d been so anxious about their departure that I missed their full glory when it was right in front of me.

On the other hand, if an experience, thought, or feeling is painful, our tendency is to run from it or push it away. For example, if we have physical pain in one part of the body, we might find the rest of our body tightening up, as though to ward off further discomfort. In that way, our aversion to pain adds tension and tightness to the original discomfort. Or maybe we globalize the pain and load it with judgment and recrimination. (This is all my fault. It will never change.)

Ironically we might have little direct knowledge of the pain we’re reacting to because we’re scrambling so fast to make it leave, often in ways that make it worse. What we have to understand is that there’s a big difference between pain and suffering. We can have a painful physical experience, but we don’t need to add the suffering of fear or projection into the future or other mental anguish to it. Mindfulness can play a big role in transforming our experience with pain and other difficulties; it allows us to recognize the authenticity of the distress and yet not be overwhelmed by it.

And if an experience is neutral, ordinary, we tend to disconnect from it or ignore it. We live in a fog, or in our heads, oblivious to many daily moments that might offer the possibility for richness in our lives. In an ordinary day we can be moving so fast that we lose touch with quieter moments of happiness that could nourish and sustain us. Some of us may come to believe we need a dose of drama—good or bad—or a jolt of adrenaline to wake us up and make us feel alive; we get hooked on risks and thrills.

When we can’t let the moment in front of us be what it is (because we’re afraid that if it’s good, it will end too soon; if it’s bad, it’ll go on forever; and if it’s neutral, it’ll bore us to tears), we’re out of balance. Mindfulness restores that balance; we catch our habitual reactions of clinging, condemning, and zoning out, and let them go.

Lie down in a comfortable spot with your arms by your sides and your eyes closed. Breathe naturally, as in the Week One Core Meditation. You are going to do a scan of the entire body from top to bottom as a way of getting centered—a reminder that you can be at home in your body. To begin, feel the floor (or the bed, or the couch) supporting you. Relax and allow yourself to be supported. Bring your attention to your back, and when you feel a spot that’s tense or resisting, take a deep breath and relax.

If during your body scan you detect a sensation that’s pleasant, you may feel an urge to hang on to it. If so, relax, open up, and see if you can be with the sensation of pleasure without the clinging. If you detect a sensation that’s painful, you may reflexively try to push it away; you may feel angry about it, or afraid of it. If you spot any of these reactions, see if you can release them. Come back to the direct experience of the moment—what is the actual sensation of the pain or pleasure? Feel it directly, without interpretation or judgment.

Bring your attention to the top of your head and simply feel whatever sensations are there—tingling, say, or itching, pulsing; perhaps you notice an absence of sensation.

Very slowly, let your attention move down the front of your face. Be aware of whatever you encounter—tightness, relaxation, pressure; whether pleasant, painful, or neutral—in your forehead, nose, mouth, cheeks. Is your jaw clenched or loose?

Turn your attention to your eyes, and feel the weight of your eyelids, the movement of your eyeballs in their sockets, the brush of the lashes. Feel your lips, the light pressure of skin on skin, softness, moisture, coolness. You needn’t name these things, just feel them. If you can, try to step out of the world of concepts like “eyelids” or “lips” and into the world of direct sensation—intimate, immediate, alive, ever-changing.

Return your attention to the top of your head, then move down the back of the head, over the curve of your skull. Notice your neck; any knots or sore spots?

Once again return to the top of the head, and then move your attention down the sides, feeling your ears, the sides of your neck, the tops of your shoulders. You don’t have to judge the sensations, or trade them in for different ones; just feel them.

Slowly move your awareness down the upper arms, feeling the elbows, the forearms. Let your attention rest for a moment on your hands—the palms, the backs. See if you can feel each separate finger, each fingertip.

Bring your attention back to the neck and throat, and slowly move it down through the chest, noticing any sensations you find there. Keep moving your attention downward, to the rib cage, the abdomen. Your awareness is gentle, receptive; you’re not looking for anything special but rather staying open to whatever feelings you might find. You don’t have to do anything about them; you’re just noticing them.

Return your attention to the neck, and now let your awareness move down the back of your body: shoulder blades, the midback, the lower back. You may feel stiffness, tension, creakiness, quivering—whatever you encounter, simply notice it.

Now bring your attention into the pelvic area and see what sensations you feel there. Slowly move your awareness down your thighs, your knees, your calves, and all the way down your legs, feeling the ankles. Settle your attention into your feet.

When you feel ready, open your eyes.

As you end the meditation, see if you can continue to feel the world of sensation and all of its changes, moment by moment, as you move into the activities of your daily life.

Walking meditation is—literally—a wonderful step-by-step way of learning to be mindful, and of bringing mindfulness into everyday activity. It becomes a model, a bridge, for being mindful in all the movements we make throughout the day.

The essence of walking meditation is to bring mindfulness to an act that we normally do mechanically. So often when we’re getting ourselves from place to place, we’re on automatic pilot, hurrying because we’re looking forward to a rendezvous or late for a meeting. Maybe we’re planning our excuse, imagining what the other person will say, and what our response will be. We get so caught up in the story that we miss the journey. So in this meditation we shed the story and bring our attention to the basics—the sensations of our body moving through space.

Instead of following your breath, as in the Week One Core Meditation, you’ll let your attention rest fully on the sensation of your feet and legs as you lift them, move them through space, and place them on the ground. Most of the time we have the sense that our consciousness, who we are, resides in our head, somewhere behind our eyes. But in this meditation, we’re going to put our feet in charge. Try to feel your feet not as if you’re looking down at them, but as if they’re looking up at you—as if your consciousness is emanating from the ground up.

You may practice either inside or outside. Be sure you have enough space to walk at least twenty steps, at which point you’ll turn around and retrace your path. If it’s possible, you can also do your walking meditation outdoors where you won’t need to turn around. While you’re walking, your eyes will, of course, be open, and you’ll remain fully aware of your surroundings, even though your focus will be on the movement of your body.

Start by standing comfortably with your eyes open at the beginning of the path you’ve chosen. Your feet are shoulder-width apart, your weight evenly distributed upon them. Hold your arms at your sides in whatever way seems comfortable and natural, or clasp your hands lightly behind your back or in front of you.

Now settle your attention into your feet. Feel the tops of your feet, the soles; see if you can feel each toe. Become aware of your foot making contact with your shoes (if you’re wearing them) and then the sensations of your foot making contact with the floor or ground. Do you feel heaviness, softness, hardness? Smoothness or roughness? Do you feel lightly connected to the floor or heavily grounded? Open yourself to the sensations of contact between foot and floor or ground, whatever they might be. Let go of the concepts of foot and leg and simply feel those sensations.

Still standing comfortably, begin slowly to shift your weight onto your left foot. Notice each subtle physical alteration as you redistribute your weight—changes in balance, the way your muscles stretch, strain, and relax again, any cracking or popping in your ankle. Maybe there’s a little trembling in the leg bearing the weight, maybe your leg feels supple or strong.

Very slowly and carefully, begin to move back to the center, with your weight equally distributed on both feet. Then shift your weight onto your right foot and leg. Once again notice what your body feels as you make this adjustment. Be aware of the difference between the weight-bearing leg and the left leg.

Gently come back to center and stand comfortably for a moment.

Now you’ll begin walking, with the same deliberate movement, the same gentle attention that you just practiced as you shifted your weight. Remain relaxed but alert and receptive. Walking at a normal speed, focus on the movement of your legs and feet. Notice that you can focus on the feeling of your feet touching the ground and at the same time be aware of the sights and sounds around you without getting lost in them. It is a light attentiveness to the sensations of movement, not a tight focus. The sensations are like a touchstone for us. You can make a quiet mental note of touch, touch.

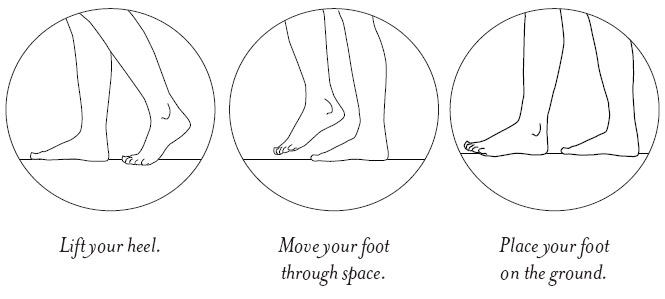

After a few minutes, see if you can slow down a bit and be aware of what it feels like as you lift the heel, then the whole foot; what it feels like when you move your leg through space and place your foot. Make a simple mental note each time your foot lifts and each time it touches the ground, lift, place; lift, place or up, down; up, down to anchor your attention.

If you’re outside, you may find yourself distracted by people moving around you, the play of sun and shadow, the barking of a dog. That’s okay; just return to focusing on your feet touching the ground. When you notice that your mind is wandering, bring your attention back to the stepping, the sensation of movement. Notice that the very moment you recognize that you’ve been distracted, you’ve already begun again to be aware.

After some minutes, slow your walking down further and divide the step into three parts: lift, move, place or up, forward, down. Finish one step completely before you lift the other foot. See if you can detect the specific sensations associated with each small part of the step: lifting the heel, lifting the whole foot, moving the leg forward, placing the foot down on the ground; the sensation of touching, of shifting your weight, of lifting the other heel, and then repeating the process. The rhythm of this slow walking is quite different from the rhythm of the way we usually move. It might take a while for you to get used to this new pace and cadence: lift, move, place, and come to rest. Only then lift the back foot.

Though your attention is on your feet and legs, you may occasionally want to check in with the rest of your body. Become aware of the sensations in your leg, hips, back—pressure, perhaps, stiffness or fluidity. No need to name them, though; just feel them. Then come back to the sensations in your feet and legs. Feel the slight bounce as your foot meets the ground and the security of the earth holding you up.

Keep the noting—lift, move, place—very soft and your movements graceful, as if this slow walking were a martial arts exercise, or a kind of dance step. Lift, move, place. Lift, move, place. Stay with the feeling of what you’re experiencing right now, in just this moment.

Newcomers to walking meditation may feel a bit wobbly—and the more slowly you move and the more aware of your feet you become, the more unbalanced you feel. If that happens, speed up a bit. Do the same if your mind starts wandering a lot, or you’re having trouble connecting with your bodily sensations. Then slow down again when your concentration is restored. Experiment with pace until you find the speed that best allows you to keep your attention on the feeling of walking —the speed that allows you to remain most mindful.

And after twenty minutes or so of walking, simply stop and stand. Notice what you feel at the point where your feet meet the floor or ground; take in what you see and hear around you. Gently end the meditation.

Remember that at any place and at any time throughout the rest of your day, you can bring mindfulness to a movement, becoming aware of how your body feels as you stand, sit, walk, climb stairs, turn, reach for the telephone, lift a fork at mealtime, or open the front door.

If walking is a problem for you, you can do this meditation without actually walking. Instead, sit (or lie down if you’re bedridden) and focus your awareness on another part of the body—moving your hand up and down, say—or on the sensations of wheeling if you’re in a wheelchair. When the instructions call for slow, deliberate, focused movements of the legs and foot, do the same with whatever part of the body you’re using.

Sit comfortably on the floor with your legs crossed and your back straight, or lie on your back with your arms at your sides. Your eyes may be open or closed.

Begin with hearing: Be aware of any sounds that reach you. Let them come and go; you don’t have to do anything about them.

Now bring the same relaxed and open awareness to your breath, at the nostrils, the chest, or the abdomen, wherever you detect it most clearly. If you wish, make a quiet mental note on each inhalation and exhalation—in, out, or rising, falling.

The breath is the primary object of awareness here until a physical sensation is strong enough to take your attention away. If that happens, rather than struggle against it, let go of the awareness of the breath, and let your attention settle fully on the bodily sensation that has distracted you. Let it become the new object of your meditation.

If it’s helpful to you, make a quick, quiet mental note of whatever you’re feeling, whether it’s painful or pleasing: Warmth, coolness, fluttering, itching, ease. No need to find exactly the right words—-noting just helps bring your mind into more direct contact with the actual experience. You’re not trying to control what you feel in your body, nor are you trying to change it. You’re simply allowing sensations to come and go, and labeling them, if that’s helpful to you.

If the sensation that has claimed your attention is pleasant—a delicious sense of looseness in your legs, say, respite from a chronic ache, or a calm, floaty lightness—you may have the urge to grab onto it and make it last. If that starts to happen, relax, open up, and see if you can experience the pleasure without the clinging. Observe the sensation, and allow it to leave when it leaves.

If the sensation arising in your body is unpleasant or painful, you may feel a reflexive urge to push it away. You may feel annoyed by it, or afraid of it; you may feel anxious, or tense. Note any of these reactions, and see if you can come back to your direct experience. What’s the actual sensation, separate from your response to it?

If what you sense is a pain, observe it closely. Where do you feel it? In more than one place? How would you describe it? Although at first, pain seems to be monolithic and solid, as we look carefully we see that it’s not just one thing. Maybe it’s actually moments of twisting, moments of burning, moments of pressure, moments of stabbing. Does the pain grow stronger or weaker as you observe it? Does it break apart, disappear, return intermittently? What happens between twists or stabs? If we’re able to detect these separate components of the pain, then we see that it’s not permanent and impenetrably solid, but ever-changing; there are spaces of respite between bursts of discomfort.

See if you can zero in on one small detail of it. Rather than take in every sensation that’s happening in your back, for example, look at the most intense point of pain. Observe it. See if it changes as you watch it. If it’s helpful to you, quietly name those changes. What’s actually happening in this moment? Can you see the difference between the painful sensation, and any conditioned responses you’re adding to it, such as fighting it, fearfully anticipating future pain, or criticizing yourself for having pain?

If a troubling thought distracts you, let it go. If it’s an emotion, focus your attention and interest on its physical properties instead of interpreting or judging it. Where do you feel the emotion in your body? How does it affect or change your body? Whether the physical sensation is pleasurable or painful, continue to observe it directly.

Don’t try to stay with painful sensations uninterruptedly for too long. Keep bringing your attention back to the breath. Remember that if something is very challenging, the breath is a place to find relief, like returning to home base.

Allow your attention to move among hearing, following the breath, and the sensations in your body. Mindfulness remains open, relaxed, spacious, and free, no matter what it’s looking at. If you feel a physical sensation especially strongly, briefly scan the rest of your body. Are you contracting the muscles around the painful sensation? Are you trying to hold on to a pleasant sensation, bracing your body against its departure? In either case, take a deep breath and relax your body and mind. Pain is tough, but it’s going to leave us. Pleasure is wonderful, but it’s going to leave us. You can’t hang on to pleasure; you can’t stop pain from coming; you can be aware. When we practice mindfulness, we don’t have to take what’s happening and make it better, or try to trade it in for another experience. We just allow the mind to rest on whatever is capturing our attention.

Gently end your meditation. See if you can bring the feeling of being centered within your body, of directly experiencing your ever-changing sensations, into the rest of your day. A few times a day, stop whatever you’re doing and become aware of your body. See which sensations predominate. Try to have a direct physical and tactile experience as you’re performing everyday activities—feel a water glass against your hand as a cool hardness; when you sweep the floor, sense the exertion in your arms, the tug on the muscles of your back and neck.

A friend told me that he’d decided to make brushing his teeth a mindfulness exercise—to slow down and concentrate on each separate step of this usually automatic task. The first thing he noticed, he said, was that he was holding on to the toothbrush so tightly it might have been a jackhammer about to leap out of his hand. He felt this was a useful clue, an indication perhaps that he was using inappropriate force or energy in other activities, from the way he made his bed to the way he held his body as he lay down to sleep.

Often we can take the lessons we learn from observing one single activity and apply them to the rest of our life. See if you can use a part of your everyday routine as a meditation, a time of coming into the moment, paying attention to your actual experience, learning about yourself, deepening your enjoyment of simple pleasures, or perhaps seeing how you could approach a task more skillfully.

Choose a brief daily activity—something you may have done thousands of times but never been totally conscious of. This time bring your full awareness to it; pay attention on purpose. Here’s a mindfulness exercise you might try:

How many times a day do we perform an action without really being there? When we’re simultaneously reading the newspaper, checking our e-mail, having a conversation, listening to the radio, and drinking a cup of tea, where is the taste of that tea? In this exercise we try to be more fully present with every component of a single activity—drinking a cup of tea.

Put aside all distractions, and pour a cup of tea. Perhaps you’ll want to make brewing the tea a meditative ritual. Slowly fill the kettle, listening to the changing tone of the water as the level rises, the bubbling as it boils, the hissing of steam, and the whistle of the pot. Slowly measure loose tea into a strainer and place it in the pot, and inhale the fragrant vapor as it steeps. Feel the heft of the pot and the smooth receptivity of the cup.

Continue the meditation as you reach for the cup. Observe its color and shape, and the way its color changes the color of the tea within it. Put your hands around the cup and feel its warmth. As you lift it, feel the gentle exertion in your hand and forearm. Hear the tea faintly slosh as you lift the cup. Inhale the scented steam; experience the smoothness of the cup on your lip, the light mist on your face, the warmth or slight scald of the first sip on your lips and tongue. Taste the tea; what layers of flavor do you detect? Notice any leaf bits on your tongue, the sensation of swallowing, the warmth traveling the length of your throat. Feel your breath against the cup creating a tiny cloud of steam. Feel yourself put the cup down. Focus on each separate step in the drinking of tea.

Restore your attention, or bring it to a new level, by dramatically slowing down whatever you’re doing. If you’re eating lunch, feel the sensation of the food on your tongue or the pressure of your teeth as you chew, your holding of a fork or spoon, the movement of your arm as you bring the food to your mouth. These specific components of an action may be invisible as you speed through your day.

Try slowing down when you’re washing dishes, bringing your awareness to every part of the process—filling the sink with water, squirting in the detergent, scraping the dishes, immersing them, scrubbing, rinsing, drying. Don’t hurry through any of the steps; zero in on the sensory details. See if you can be in the present moment as you wash one item. Do you feel calm? Bored? Notice your emotions as they come and go—impatience, weariness, resentment, contentment. Whatever thoughts or feelings arise, try to meet them with the gentle acknowledgment, This is what’s happening right now, and it’s perfectly okay.

You may notice that many judgments come to mind: I chose the wrong tea. I drink too much tea. I don’t give myself enough time to enjoy tea. I should be paying bills, not sniffing tea. Am I running out of tea? Note these thoughts, and let them go. Simply return to the direct experience unfolding in the moment. Just now; just drinking tea.

Some people who try the walking meditation for the first time don’t feel their feet until they look down. The exercise eases us into greater connection with physical sensations as they’re happening—so we don’t become like the thoroughly disconnected Mr. Duffy in James Joyce’s short story “A Painful Case,” who “lived at a little distance from his body.” Walking in this slow, contemplative way gives us a fresh, immediate experience of our bodies—not a rumor of our feet, or what we remember about our feet, but what our feet feel like that very second. This meditation helps us bring mindful movement into our daily lives.

The Body Sensation Meditation offers a way to see the difference between direct experience of our bodies and the habitual, conditioned add-ons we carry with us. It’s especially useful in helping us learn to let sensations arise and subside naturally, without clinging, condemning, or disconnecting. Those three conditioned responses can rob us of a good many chances for authentic happiness. How many times has the wonderful moment in front of us been poisoned because we’re fretting over its anticipated departure? I think about a new mother who told me she caught herself feeling such wistfulness at how fast her baby was growing up and away from her that she almost didn’t see the lovely child in her arms right then. How many times has an attempt to dodge pain made us miss the sweet parts of bittersweet—the chance to grow in response to a challenge, to help others or accept help from others? How many pleasures escape our notice because we think we need big, dramatic sensations to feel alive? Mindfulness can allow us to experience fully the moment in front of us—what Thoreau calls “the bloom of the present”—and to wake up from neutral so we don’t miss the small, rich moments that add up to a dimensional life.

The Body Sensation Meditation is also especially helpful in pointing us toward a mindful approach to pain. It trains us to be with a painful experience in the moment, without adding imagined distress and difficulty. If we look closely at it, the pain is bound to change, and that’s as true of a headache as it is of a heartache: the discomfort oscillates; there are beats of rest between moments of unpleasantness. When we discover firsthand that pain isn’t static, that it’s a living, changing system, it doesn’t seem as solid or insurmountable as it did at first.

We can’t avoid pain—but we can transform our response to it. One of my students used the Body Sensation meditation to deal with intractable chronic pain, eventually diagnosed as Lyme disease. Again and again, she brought her awareness back to what she was experiencing in the moment, the one moment in front of her. She observed her pain, she said, the way the tide of it surged and receded, its location, the routes it traveled, its shape and texture—sometimes pulsing, sometimes radiating, sometimes jagged as lightning bolts. She watched closely to see how her pain, like everything else in the world, changed. And she found moments of respite that were sustaining to her. She didn’t get rid of the pain, but, she told me, “I found the space within the pain.”

The science is interesting on this point: Researchers are discovering that for some people, meditation can actually diminish the perception of pain. In 2010, British scientists found that longtime meditators seem to handle pain better than the rest of us because their brains are less focused on anticipating it. After using a laser to induce pain in study participants, the scientists then scanned their brains. Experienced meditators showed less activity in the areas of the brain normally turned on when we anticipate pain, and more activity in the region involved in regulating thinking and attention when we feel threatened. “The results of the study confirm how we suspected meditation might affect the brain,” explained Dr. Christopher Brown, of the University of Manchester, the chief researcher. “Meditation trains the brain to be more present-focused and therefore to spend less time anticipating future negative events.”

Q: Won’t zeroing in on pain, making it the object of attention, just make it worse?

A: Sometimes approaching pain with pinpoint awareness is useful, so that you’re feeling it just at its most acute or intense point. At other times it’s more useful to step back and be with the pain in a broader way—noticing it fleetingly and then letting it go. What’s most important is to approach the pain with a spirit of exploration: For whatever time you’re focusing on it, are you open to it, interested in it, paying attention to it? Or are you filled with fear and resentment, drawing conclusions and making judgment about the pain?

Dealing with pain is not a question of endurance, sitting with your teeth gritted and somehow making it through, even if you’re feeling great distress at what is happening. Our practice is, as much as possible, to recognize our experience without getting lost in old, routine reactions. The point is to be open not just with pain, but with everything.

Q: I find walking practice much easier than sitting. But is walking “real” meditation?

A: We can practice meditation in four different postures: sitting, standing, walking, and lying down, and each one is equally “real,” a complete practice in itself. The obvious difference among them is energy. Meditating lying down will likely generate the least energy, while walking will produce the most. Sometimes people choose to do walking meditation instead of sitting when they’re feeling foggy or drowsy. Walking is also a good alternative to sitting when we feel restless and need to channel the extra energy coursing through our bodies. Walking won’t disperse that energy but will help direct it so that we experience more balance.

Q: When I’m doing walking meditation, it’s hard for me not to notice everything going on around me. What should I do?

A: There are certainly times when something in the environment draws our attention dramatically. In that case, you might just stop walking and pay full attention to whatever it is for a few moments before letting it go. But if you find yourself stopping every ten seconds because your attention is being snagged by every bird, leaf, or passerby, you might need to shift toward paying more attention to the sensations of movement—not shutting out everything that’s happening around you, but not letting your surroundings draw your attention away completely. Aim for a balance.

Q: Sometimes when I meditate after work, my body feels tense and twitchy, and I’m distracted. Would I have a better meditation if I did some yoga or other stretches first?

A: Knowing this about yourself is a good start. First I’d suggest doing a walking meditation before you sit if you tend to feel restless at the outset. Or you could replace the seated session altogether with a walking meditation if you’re in a place where that’s possible.

Another option: Right before doing a seated meditation, take five or ten minutes to stretch your body, or do a couple of yoga postures that you know get rid of kinks. Stretch in any way that your body is telling you it needs. Then settle in to your seated posture and begin your meditation session. See if your body has quieted down enough to free you to pay attention to the breath. Of course, if you feel agitation or discomfort while seated, try to be with these feelings in a balanced way to see what you can learn from them.

Q: Sometimes my back and knees really hurt when I sit with my legs crossed—so much that I want to quit. Should I sit in a chair?

A: You could certainly sit in a chair, or you could wait to see whether your back hurts less as you become more familiar with the cross-legged position. You should also check to see if your body is supported and you are sitting in good alignment—do you need cushions under your knees or to add another cushion for height, for example? You might also experiment with seeing what you can learn from the discomfort. Locate it precisely in your body. Be with the sensation for a few moments and watch to see if it changes. As you observe, it may grow stronger or weaker; it may move around, it may stay the same. Approach it with a spirit of exploration: What am I actually experiencing? Is it totally unpleasant? Is anything about it comfortable? Is it changing? See what you’re telling yourself about the pain. I shouldn’t have this pain. I hate this pain. If I still have this pain in half an hour, I won’t be able to stand it. Try to make a quiet mental note of just what you’re experiencing in the moment directly, without judging it, adding to it, holding onto it, or pushing it away. Once you’ve noted the sensation, return your attention to the feeling of the breath. If you find that you’re fighting the pain, hating it, it’s better to change your posture and begin again. But try seeing what happens when you don’t relate to the pain in your usual way and instead observe it with an open mind.

For most of us, mindfulness is fleeting. We manage it for a moment, and then we’re gone again for a long period of time, preoccupied with the past, the future, our worries; we see the world through the goggles of long-held assumptions. What we’re doing in practice is working to shift the ratio, so that we can gather and focus our attention more frequently. Mindfulness isn’t difficult; we just need to remember to do it.

One new meditator, a lawyer, said that the walking meditation led him to focus on small physical details he’d previously missed. “I, a noted curmudgeon, find that I’m very grateful for things like a breeze or the sun on the back of my neck. The other day I made it a point to pay attention to the sun and the wind, and how good they felt, as I walked from my office to a meeting that could have been tense. I arrived in a pleasanter frame of mind, more open to hearing the other person’s point of view. The meeting went much better than I’d expected. They don’t teach sun and wind in law school.”

Often people think, I don’t have the right kind of mindfulness, the right level of concentration. Progress is not about levels; it’s about frequency. If we can remember to be mindful, if we can add more moments of mindfulness, that makes all the difference. Countless times a day we lose mindfulness and become lost in reaction or disconnected from what is happening. But the moment we recognize that we’ve lost mindfulness, we have already regained it; that recognition is its essence. We can begin again.

*Listen to tracks 4 and 5 from the audio meditations