Just steps away from the sycamore-lined northern stretches of Vali’asr Street, near the wealthy Tajrish district, the Cinema Museum (Muzeh-ye sinemā) stands impressive in Tehran’s historic Ferdows Garden (Bāgh-e ferdaws), among some of the city’s most stylish boutiques and cafés. A placard at the entrance informs visitors about the historical significance of the museum’s context and surroundings: a garden that dates back to the reign of Mohammad Shah Qajar (1834–1848); the establishment of a school during Reza Khan’s rule in the 1930s; efforts to turn the space into an artistic and cultural center in the 1950s; and the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance’s control of the building after the revolution of 1978–1979. The museum’s location in Ferdows Garden and its description of the site attest to the cultural value of cinema in Iran, or at least to the museum’s ambitions for cinema as high art, a designation wherein the film industry is an elite cultural institution that has helped to write the Iranian national narrative. I visited the Cinema Museum during the summer of 2014, and despite the ways in which the museum positions itself with regard to this narrative, the experience of navigating through the building’s various hallways and corridors reveals the museum as a distinctly reformist institution.

The placard at the garden’s entrance betrays the urgency of situating the museum—and by extension cinema as a whole—historically, an urgency that grows out of the museum’s relative youth. The Cinema Museum, the only one of its kind in Iran, was formally established in 1998 and opened its doors to the public in its current location in 2002. Whereas the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance and other government offices house film and video archives in Iran, the Cinema Museum is unique as a public research institution that exhibits the history of the film industry and that archives documents related to Iranian cinema. On entering the museum building, visitors do not encounter an old camera, a film canister, or even a movie poster but, rather, run into another placard, one that describes the circumstances surrounding the founding of the Cinema Museum. The description establishes a cast of characters who helped bring the museum to fruition. These include Mohammad Beheshti, the first director of the Farabi Cinema Foundation, cited as the impetus for the museum’s establishment; the deputy of cinematic affairs (Seyfollah Dad); and Mohammad Khatami, who was present at the museum’s opening in Ferdows Garden. These three men, in addition to their work supporting the film industry in Iran, are reformist politicians, and the emphasis on their contributions to the museum’s establishment positions it as a reformist effort.

The Cinema Museum began its work in 1998, and a ceremony in honor of the museum’s establishment was held on May 25, 1998. Just two days earlier, on the one-year anniversary of Khatami’s election, celebrations among his supporters had swept through the country. The date of the museum’s founding therefore takes on special significance; holding the ceremony almost exactly one year after Khatami’s election situated the museum politically within reform, part of the changing cultural sphere. The way in which the museum’s founders imagined it also spoke to this positioning. Seyfollah Dad, who had directed Mohammad Khatami’s campaign movie just a year earlier, was serving as the deputy for cinematic affairs at this time. At the museum’s inauguration Dad stated that “the opening of the museum is an instrumental step in advancing and distinguishing Iranian cinema, and it is an effort to preserve the works, masterpieces, and relics of the history of Iranian cinema.”

1 To this end, the museum’s founders envisioned not only exhibits that display the material history of Iranian cinema but also a library that preserves its rich textual history. At the time of its founding, the museum had already amassed a collection of 4,000 publications related to Iranian cinema, and one of the chief aims of the museum at this time was to publish reports on these archival materials. The museum endeavored to publish these reports in other languages as well so non-Iranians could also use them.

2 The museum thus envisioned Iranian cinema as a barometer for the success of the Islamic Republic and as a means of diplomacy. This vision of Iranian cinema was radically different from a revolutionary cinema that privileged ideology over aesthetics and anti-imperialism over diplomacy. Within the Cinema Museum, Iranian cinema is not simply at the service of the Islamic Republic as an instrument for propaganda but is, rather, a discursive feature of Iranian culture, battling for authority in art, politics, and ideology.

The Cinema Museum, as a reformist institution, reaffirms reform cinema as a distinct period within the history of Iranian film, one that tracked aesthetic and political changes but also witnessed new institutional support, like the museum. Reform cinema, the inheritor to revolutionary cinema, marked legal changes and new discursive operations within and with regard to the film industry. New laws regulated the oversight of video technology, looser interpretations of censorship codes prevailed, and filmmakers developed new aesthetic strategies to contribute to the discourse of political reform. At the same time, the rise of reformist politics in Iran also facilitated new institutional support for the film industry, including the Cinema Museum. We can see traces of this institutional support in the country’s cinema-related periodicals as well. For example, in the first twenty-five years of the Islamic Republic there were forty-four film journals, and seventeen of them (or more than one-third) were established during Khatami’s presidency. Similarly, in the eighteen years between the revolution and Khatami’s election, 520 books related to cinema were published; in contrast, during the first seven years of Khatami’s presidency a staggering 676 books on the topic of cinema were published, more than the total sum of books published in the prior period.

3 The surge in cinema-related publishing during Khatami’s presidency was part of the reformist push to foster a free press within the country.

4 The institutional support of cinema that developed in tandem with the rise of political reform, such as new publications and venues for scholarship and the Cinema Museum, reminds us that reform cinema fostered not just aesthetic changes but also the centralization and stabilization of the film industry. The establishment of the multifaceted film culture that we associate with cinema within the Islamic Republic thus grew out of reformist politics and not just the initial enthusiasm of the revolution.

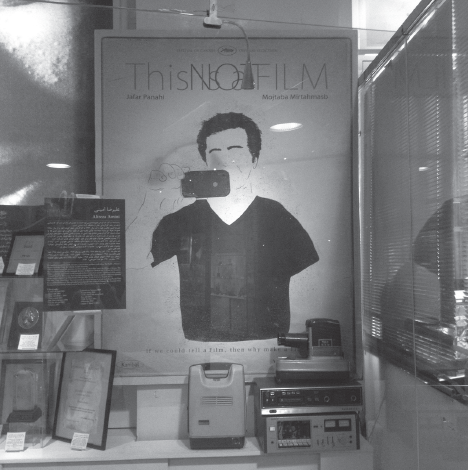

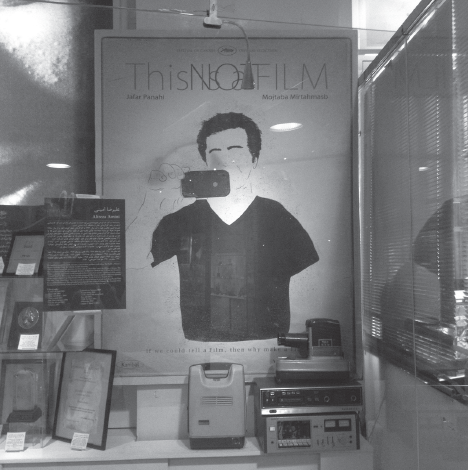

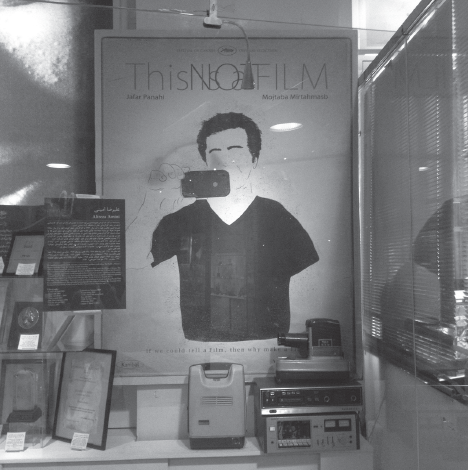

Central to the Cinema Museum’s vision of Iranian cinema is the film industry’s role as a diplomat, a cultural interlocutor that responds to Mohammad Khatami’s call for a “dialogue among civilizations.” To this end, the museum’s third and largest hall is devoted specifically to displaying the awards that filmmakers have won at international film festivals, including Abbas Kiarostami’s Palme d’Or. Iranian film posters from around the world adorn the walls and displays of this hall, which makes it one of the most visually exciting spaces within the museum. Tucked away deep inside the building, this hall is also full of surprises, and when visitors enter, they are immediately greeted by a large poster for

In film nist (This is not a film, 2011), a movie directed by Jafar Panahi and Mojtaba Mirtahmasb (

figure C.1). On this poster, a black-and-white sketch of Panahi holds an iPhone pointed directly at the onlooker, and he seems to be recording us, tracking our every move, and implicating us in some larger project of witnessing. The poster captures the movie’s dizzying convergence of technology, politics, and storytelling, and its prominent place within the Cinema Museum is shocking because

This Is Not a Film was produced underground, without any permits, and it defiantly pushes back on the twenty-year ban on filmmaking (

mahrumiyat az filmsāzi) that the Islamic Republic’s Revolutionary Court issued Panahi in December 2010.

FIGURE C.1 The poster for Jafar Panahi’s This Is Not a Film in the Cinema Museum in Tehran. Photograph by the author.

The story of

This Is Not a Film’s

arrival at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival, where it received a special out-of-competition screening, has all the trappings of a Hollywood action movie.

This Is Not a Film arrived in France on a USB stick that had been hidden in a cake that was sent from Iran to Paris.

5 Mirtahmasb, who had previously served as Panahi’s cameraman, shot

This Is Not a Film on an iPhone as well as the more traditional digital video camera. The movie, filmed over just four days, purportedly examines a day in the life of Panahi in his home as he anxiously awaits the start of his six-year jail sentence. In December 2010 Tehran’s Revolutionary Court convicted him of conspiring to commit crimes against national security and of spreading propaganda against the Islamic Republic, charges typically filed against dissident artists. He was sentenced to six years in prison and was issued a twenty-year ban on making films, leaving the country, and talking to foreign media. Many people, however, speculate that Panahi’s real crime was supporting the efforts of Jonbesh-e sabz (the Green movement), a grassroots initiative calling into question the legitimacy of the 2009 electoral results that guaranteed Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s second term as president.

The Green movement began as a series of mass demonstrations following the announcement of Ahmadinejad’s victory, and these demonstrations marked the largest protests in Iran since the revolution thirty years earlier. Supporters of the movement rallied around Mir-Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karoubi, the two reformist candidates who had challenged Ahmadinejad. Mohammad Khatami was also originally on the ballot, but he withdrew his candidacy during the campaigning period and endorsed Mousavi in an effort not to split the reformist vote. Following the initial wave of protests, at a time when it seemed like the country was once again on the verge of revolution, Mousavi, Karoubi, and Khatami became the ex post facto leaders of a movement that sought to reform the political system in Iran, especially in light of Ahmadinejad’s neoconservative politics and Ayatollah Khamenei’s unilateral support of Ahmadinejad’s election. Although the Green movement ultimately failed to unite around a single set of goals and eventually broke down, especially after Mousavi and Karoubi were placed under house arrest, the Green movement enjoyed widespread support during the year that followed the 2009 elections, especially among Iran’s youth.

Iranian filmmakers, both those based in Iran and those based outside of the country—including Marjane Satrapi, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Jafar Panahi, and Mohammad Rasoulof—voiced their support of the young protestors. In spring 2010, Panahi and Rasoulof were arrested while shooting a fictional film they were codirecting about the devastating effects of the government’s crackdown on personal liberties following the rise of the Green movement. Prior to his arrest, in September 2009, Panahi convinced all of the jurists at the Montreal Film Festival to wear green scarves in support of the Green movement in Iran, and this defiant move, along with the unpermitted movie, was added to the list of charges launched against him during his sentencing. Following his initial sentencing, Panahi was released from jail, but since that time he has been subject to a policy in Iran known as habs-e ta‘ziri (suspended sentence). This policy means that although Panahi is not currently serving his six-year jail sentence, the courts could send him to prison at any time.

Despite the tenuousness of his situation, Panahi has refused to stay quiet, and he has continued to make movies and conduct interviews with foreign media outlets.

This Is Not a Film was the first movie that he made following his sentencing, and its arrival at Cannes surprised those familiar with the politics of culture in Iran. Many film critics have been distracted by its unconventional submission to Cannes and the details of Panahi’s arrest; however, the movie is ultimately a complicated exploration into what it means to make a film in Iran and how reformist politics have refashioned filmmaking in the country. The title,

This Is Not a Film, calls film as a category into question, a designation that is particularly important in Iran because Persian does not have a platform-neutral word like “movie.” Instead, in Persian all movies are films, even if they only exist in a digital format, like

This Is Not a Film, which arrived at Cannes on a flash drive rather than in a film canister. The movie’s title gestures toward the epistemological limitations of “film” in Persian, and Mirtahmasb and Panahi capitalize on these limitations by suggesting that their movie is not a film and thus not covered in the terms of Panahi’s ban on filmmaking. The use of video, and iPhone video footage in particular, allows Mirtahmasb and Panahi to sidestep the governmental approval process, even as they challenge the democratic vision of video that reform cinema helped establish.

This Is Not a Film is replete with tricks that reveal that as much as digital video technology frees the director, as Kiarostami claimed, video footage in turn deceives the viewer. At one point, Panahi even directly addresses the camera and declares, “I feel like what we are doing here is also a lie.”

In

This Is Not a Film,

Mirtahmasb and Panahi use medium as a launching point for a larger inquiry into the nature of filmmaking, accountability, and authority. Storytelling is central to this inquiry, and Panahi devotes a large portion of

This Is Not a Film to a script that had recently been rejected by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. In this script, a young woman has been accepted to study art at university, but her parents, who disapprove of her plans, lock her in their house instead. Of course, the similarities to Panahi’s captivity in

This Is Not a Film are not meant to go unnoticed, and this is one way that Mirtahmasb and Panahi misguide us. Despite the fact that Panahi has never been placed under house arrest, the sense of captivity that Panahi creates with the claustrophobic video shots and the references to house arrest in the rejected script have caused film critics to assume erroneously that Panahi was under house arrest when

This Is Not a Film was shot, and even the movie’s description on Amazon.com claims that the film takes place “during his house arrest in Tehran.” At one point, Panahi reads from the rejected script and constructs the interior space of the young woman’s home-jail using masking tape on his carpet. He abruptly stops in the middle of constructing the imaginary floor plan, however, and asks the camera, “If we could tell a film, why make a film? Or, indeed, why write about one?” These questions return to the movie’s title.

This Is Not a Film does not attempt to tell a story or advance a plot, and by this measure it is not a film, according to the definition that Panahi introduces.

Although it claims not to be a film at all, This Is Not a Film builds off the concerns that Panahi raised in his previous three films: Dāyereh (The circle, 2000), Talā-ye sorkh (Crimson gold, 2003), and Āfsāyd (Offside, 2006). These three films examine individuals who push the legal limits in Iran and often suffer the consequences. Rather than condemning these criminals, however, Panahi’s camera sympathetically positions them as victims of social disparity and an unfair legal system. In This Is Not a Film, Panahi is the criminal who is represented sympathetically onscreen. This Is Not a Film thereby inverts many of the normative features of film, and it creates a space in which the director becomes a character; the cameraman becomes the director; scripts are read rather than performed; iPhones replace 35 mm film cameras; three-dimensional spaces (like houses) are reduced to two-dimensional masking tape lines; and a film is not even a film. In light of the political events surrounding this project, This Is Not a Film ultimately demonstrates how the cry for reform in the Islamic Republic has affected filmmaking and has refashioned many of its conventions.

The poster for

This Is Not a Film in

the Cinema Museum thus testifies to the ways in which reform cinema has reorganized what it means to make a film in Iran, and how certain film institutions have been implicated in this process. But the poster’s presence is more than just a relic of reform cinema. It is also a statement of protest, and its position within the Panahi display case appears to be a sleight of hand on the part of the museum’s curators. On October 20, 2010, Panahi appeared in court to face his sentencing, and he read aloud a statement outlining his defense, which was later published online. In this statement, he asked, “Is there anyone in this court who recalls that the display case for Jafar Panahi’s awards at the Cinema Museum is much bigger than his prison cell was during his arrest?”

6 Of all of Panahi’s internationally successful films,

This Is Not a Film is the only one to feature an image of Panahi on its poster. To see Panahi held captive in this display reminds us of just how political filmmaking had become, especially in Ahmadinejad’s Iran.

To this end, This Is Not a Film and its prominent place in the Cinema Museum unearth one of the most important implications of reform cinema in Iran. Beginning with its rise in the early 1990s, reform cinema marked the exact point at which revolutionary politics were no longer radical but rather represented the old order. Political reform became the dominant progressive ideology in Iran, whereas revolutionary rhetoric became the domain of the conservative guard. Whereas Massoud Bakhshi’s Tehran Has No More Pomegranates captured the tension between revolution and reform and the instability of both of these terms, This Is Not a Film, which grew out of the political uprisings of 2009, shows us that reform cinema might easily give way to another radical revolutionary cinema. Revolutions, we are wont to remember, revolve. They circle back as reform reaches its limits.