Chapter 8

Information Requests and Complaints

Federal government agencies in the United States and Canada gather a wide array of information about people to provide essential services and to carry out their responsibilities — from issuing pension checks to enforcing laws.

However, you have the right — with some limited exceptions — to ensure the material is up-to-date and not used for unintended reasons. So how do you obtain that information?

1. Accessing Your Information in the United States

In the United States, the Privacy Act of 1974 dictates how federal agencies collect, maintain, use, and disseminate personal information.[1] The law guarantees the right:

• to see records about oneself;

• to request the amendment of records that are not accurate, relevant, timely or complete; and

• of individuals to be protected against unwarranted invasion of their privacy resulting from the collection, maintenance, use, and disclosure of personal information.

US citizens and aliens lawfully admitted for permanent residence may make a request for personal information under the Privacy Act. You can file a request by either completing a form or writing a letter to the institution in question, asking for information about yourself, or another individual, as long as that person consents. For instance, if you were making a privacy request to the US Department of Justice (www.justice.gov/usao/resources/making-foia-request/foia-frequently-asked-questions#4) you would write a letter, or complete a form (www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/oip/legacy/2014/07/23/cert_ind.pdf). Be sure to provide enough detail to allow staff to identify the relevant records.

If seeking information about yourself, you’ll be required to verify your identity in order to ensure the records are not disclosed to someone else.

There is no fee. Agencies have 20 working days to respond, though that length of time can vary depending on circumstances such as workload and the complexity of the request. Upon receipt of the request, the department will send an acknowledgment letter with a tracking number.

The outcome of a Privacy Act request may be appealed.

2. Accessing Your Information in Canada

Canada’s privacy framework consists of a network of laws operating at multiple legal layers, backed up by active privacy commissioners and a judiciary that is alive to the importance of protecting privacy in the digital age. Although navigating them can sometimes be complex, taken as a whole, Canada’s privacy laws provide some of the most effective and comprehensive privacy protections in the world.

At the federal level, there are two privacy laws that protect your information: The first is the Privacy Act, which covers about 250 departments, agencies, and Crown corporations, ranging from Indigenous Affairs and Northern Development Canada to the Yukon Surface Rights Board. The second is the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, which covers many private-sector organizations.

The Privacy Act —

• sets rules for how the federal government collects, retains, uses, and discloses your personal information;

• gives you the legal right to access and correct information held about you by the federal government; and

• puts in place and empowers an ombudsman, the Privacy Commissioner.

Canadian citizens, permanent residents, and individuals present in Canada may make a Privacy Act request.

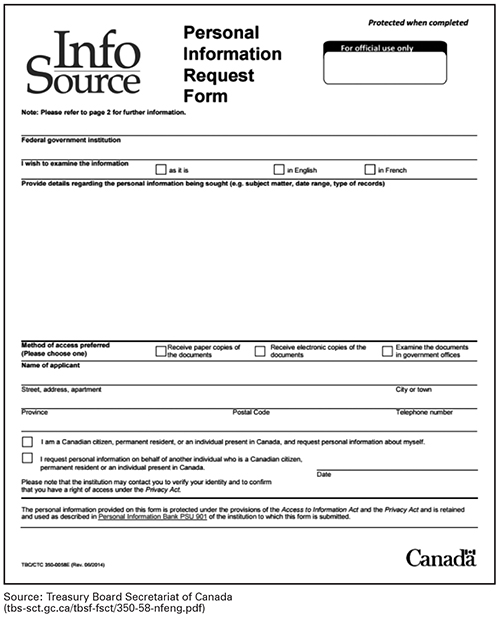

You can file an application with a federal organization by completing a Personal Information Request Form (see Sample 6) or writing a letter. As in the US, there is no fee. If you are writing a letter, be clear that you’re requesting information under the Privacy Act. Some agencies now accept requests electronically.

Sample 6: Personal Information Request Form

Send the request to the Access to Information and Privacy coordinator of the agency you believe holds your information (www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/hgw-cgf/oversight-surveillance/atip-aiprp/coord-eng.asp).

It’s important to identify yourself so the agency can be sure it is actually you asking for your personal information. The institution might contact you to verify your identity and to confirm that you have a right of access. You should also outline the information you are seeking, as being precise can speed things along.[2] Under the law, the institution in question has 30 calendar days to respond, though it may take a 30-day extension.

To find out more about the process and how it works, visit the Office of the Privacy Commissioner’s website (priv.gc.ca).

If you are unhappy with the length of time it’s taking to deal with your request, or the amount of material the institution ultimately discloses, you can complain. The process is described in more detail on the Privacy Commissioner’s website (priv.gc.ca/complaint-plainte/index_e.asp).

The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) is the rulebook for how private-sector organizations collect, use, and disclose personal information. It also covers the personal information of employees of federally regulated organizations such as airlines, banks, and telecommunications firms. PIPEDA generally does not apply to charities and other nonprofit organizations. In addition, there are exceptions when a province has legislation considered “substantially similar” to PIPEDA.[3]

In seeking access to your information under PIPEDA, you may submit a written request to the organization believed to have your personal information. You must provide sufficient detail — such as account numbers or the names of people you may have dealt with — to help the agency identify the records you want. Organizations must give you the information sought within a reasonable time and at little or no cost.

Under both the Privacy Act and PIPEDA you may complain to the Privacy Commissioner if you feel your personal information has been inappropriately handled. The commissioner is also responsible for enforcing elements of Canada’s anti-spam law.

Here is the complaint form (plainte-complaint.priv.gc.ca/en) as well as more on the process (priv.gc.ca/complaint-plainte/index_e.asp).

Confused about where to turn with your privacy issue in Canada? The Privacy Commissioner has prepared a handy guide to help (priv.gc.ca/information/pub/guide_ind_e.asp).