CHAPTER VI.

As Teacher and Preacher.

"'Tis the man who with a man

Is an equal, be he king,

Or poorest of the beggar clan,

Or any other wondrous thing

A man may be."

Keats.

By the commencement of the year 1835 we find Michael Faraday, not yet forty-four years of age, generally acknowledged as one of their peers by the leading men of science, not only in England but also on the Continent. We find him elected member of many of the most important scientific and philosophical societies of this and other countries; we find him honoured by the University of Oxford with the degree of D.C.L.; and, as we shall shortly see, we find the Government proposing to confer a pension on him in consideration of the services which he has already rendered to science. Truly a wonderful change to be wrought in the life of a man who thirty years before was carrying round newspapers as a common errand boy. It is, however, always gratifying to note, and especially pleasing to remember, that however successful he might be, Faraday was never spoiled by the honours that were done him; he was always the same kindly, helpful, simple man that he had been. Those persons who had the great good fortune to visit him at the Royal Institution, either at the time of which we are treating or during his later life, never failed to find a cordial welcome; "a friendly chat in those quiet rooms was one of the greatest pleasures it was possible to enjoy. The frugal simplicity of the furniture was characteristic of Faraday."

The Faradays lived quietly to themselves at the Institution, though they often, after the Friday evening lectures, went round to Berkley Street to tea to Mr. Richard Barlow's house, that gentleman and his wife always being at home to their friends after the Friday evenings. On such occasions as these gatherings, Faraday, we learn, used to be the centre of much interest and delight; for he had, as may be gathered from what has already been said of his character, that happy disposition which placed him at once in sympathy with any person with whom he might be speaking; especially was this rare sympathy his with regard to children, with whom he seemed at once able to place himself on an equal footing; and this it was that made his lectures to young people not only so interesting but so widely popular as they were. This subject, however, deserves fuller consideration, and will be found treated in a later chapter.

Had he chosen to do so at this period of his career, Faraday might have been in receipt of a pretty considerable income. In 1830, indeed, he had undertaken several commercial analyses, and his income from this source alone came to as much as a thousand pounds. Such work interfered with his research, and was therefore unhesitatingly given up, and two years afterwards his professional gains amounted to but little more than a hundred and fifty pounds for the year, and in after years they did not reach even that sum.

Early in 1835 Faraday received an intimation from Sir James South that had Sir Robert Peel remained in office he had intended conferring a pension upon him. Faraday wrote in reply, saying that he could not accept a pension. The matter after this remained in abeyance for a while. During the summer Faraday spent a short holiday in Switzerland, whence he wrote to his old friend Magrath: "The weather has been most delightful, and everything in our favour, so that the scenery has been in the most beautiful condition. Mont Blanc, above all, is wonderful, and I could not but feel at it what I have often felt before, that painting is very far beneath poetry in cases of high expression; of which this is one. No artist should try to paint Mont Blanc; it is utterly out of his reach. He cannot convey an idea of it, and a formal mass or a commonplace model conveys more intelligence, even with respect to the sublimity of the mountain, than his highest efforts can do. In fact, he must be able to dip his brush in light and darkness before he can paint Mont Blanc. Yet the moment one sees it Lord Byron's expressions come to mind, as they seem to apply. The poetry and the subject dignify each other."

In the autumn of the same year, shortly after his return from the Continent, the subject of a pension for Faraday was re-opened. The independence and openness of his character came out in a remarkable manner in this matter. He was asked to wait upon Lord Melbourne, the Prime Minister, at the Treasury, which he did on October 26th. However he may have spoken of Faraday personally, Lord Melbourne spoke of literary and scientific men with but scant courtesy, and in effect seemed to consider the awarding them pensions as a piece of State humbug. We have seen how Faraday resented a slur cast upon science in a court of law, and he was no less indignant on this occasion; he returned home and wrote a letter, the tone of which though dignified was very decided. This letter, in which he declined to accept or even further to consider the acceptance of a pension from the Government, Faraday intended to forward at once to Lord Melbourne. He finally, however, allowed somewhat wiser counsels to prevail; his father-in-law, while justly proud of Michael's scientific attainments, was also a shrewd business-like man, and persuaded him to write a letter, which, although it was not one whit less dignified in its tone was less decided in its refusal of the proposed pension.

After many fruitless efforts to make Faraday change his decision, a lady, who was a friend both of the philosopher and of the Prime Minister, asked the former what he would require at the hand of Lord Melbourne to make him change his mind on the subject. "I should require," he replied, "from his lordship what I have no right or reason to expect that he would grant—a written apology for the words he permitted himself to use to me." To Melbourne's credit, be it said, that as soon as he knew of this he apologised amply for, as he expressed it, the "too blunt and inconsiderate manner in which he had expressed himself."

On December 24th of the same year the pension of three hundred pounds a year was awarded to Michael Faraday for his services to the cause of science. A pension, it may here be mentioned, half of which was continued to the Professor's widow, and on her death to his niece, Miss Jane Barnard. He was not yet forty-five, we must recollect, when he was thought to have fairly earned this reward. Early in 1836 further honour was done to him by his being appointed scientific adviser to the Trinity House; in accepting the position he wrote a characteristic letter, of which the following is a portion; it was addressed to Captain Pelly, Deputy-Master: "I consider your letter to me as a great compliment, and should view the appointment at the Trinity House, which you propose, in the same light; but I may not accept even honours without due consideration. In the first place my time is of great value to me, and if the appointment you speak of involved anything like periodical routine attendances I do not think I could accept it. But if it meant that in consultation, in the examination of proposed plans and experiments, in trials, etc., made as my convenience would allow, and with an honest sense of a duty to be performed, then I think it would consist with my present engagements.... In consequence of the goodwill and confidence of all around me, I can at any moment convert my time into money, but I do not require more of the latter than is sufficient for necessary purposes. The sum, therefore, of £200 is quite enough in itself, but not if it is to be the indicator of the character of the appointment. But I think you do not view it so, and that you and I understand each other in that respect; and your letter confirms me in that opinion. The position which I presume you would wish me to hold is analogous to that of a standing counsel. As to the title it might be what you pleased almost. Chemical adviser is too narrow; for you would find me venturing into parts of the philosophy of light not chemical. Scientific adviser (the title afterwards decided upon) you may think too broad—or in me too presumptuous—and so it would be, if by it was understood all science.... The thought occurs to me whether, after all, you want such a person as myself. This you must judge of; but I always entertain a fear of taking an office in which I may be of no use to those who engage me."

This letter is, as I have said, characteristic of the writer; it is characteristic of his sensitiveness to any honour done to him, and of his unworldliness, of his conscientiousness in making sure that he will be able to perform anything that he may undertake, and of a half-diffidence with regard to himself as to whether he was able to do all that was anticipated of him. For nearly thirty years, with credit to himself and to the Brethren of the Trinity House, did Michael Faraday continue as their scientific adviser. Frequently do we find him experimenting on lights and lighting—visiting the various lighthouses round the coast, trying the electric light for them, comparing the various lights, and reporting to the Brethren—such work as this is, as has been said, to be frequently noted in looking over a record of the mass of work which during these years Faraday was doing. It is pleasing to notice here that on her husband's death Mrs. Faraday presented such of his portfolios, of well-ordered and indexed manuscripts, as referred to this part of his work to the Trinity House. So carefully were these notes made and kept that it is possible now to refer quite easily to any particular piece of work on which Faraday was engaged during these thirty years.

In this same year (1836) there appeared the Life of Sir Humphry Davy, by his brother, Dr. John Davy. In this work statements were made with relation to Faraday and his patron which were not true; and painful indeed though it must have been to the former, he felt compelled to deny them. This he did in a long letter to his friend R. Phillips, editor of the Philosophical Magazine, in which periodical the letter was published. "I regret," Faraday wrote, "that Dr. Davy has made that necessary which I did not think before so; but I feel that I cannot, after his observation, indulge my earnest desire to be silent on the matter, without incurring the risk of being charged with something opposed to an honest character. This I dare not risk; but in answering for myself I trust that it will be understood that I have been driven unwillingly into utterance."

The subject must indeed have been a painful one; to have to assert his own right to be the discoverer of certain chemical results which were being credited to Davy. In one or two cases, when he found that he had been preceded in the discovery of anything he was the first to acknowledge that all honour was due to his predecessor, and that strict regard for true honesty in all things very properly would not allow him to be silent now. He concludes his letter to Phillips in these words, "Believing that I have now said enough to preserve my own 'honest fame' from any injury it might have risked from the mistakes of Dr. Davy, I willingly bring this letter to a close, and trust that I shall never again have to address you on the subject."

It was at about this time that another incident occurred which illustrates Faraday's absolute integrity of character—integrity that would not wink at anything that was in the slightest degree not straightforward, even though it was against his own interest, which, indeed, rather shunned doing a good deed that might seem dictated by mere self-interest. His brother was working at the time as a gas-fitter, and there was a possibility of his getting the Athenæum Club work in connection with his trade. Michael, writing on the subject, said, "Few things would please me more than to help my brother in his business, or than to know that he had got the Athenæum work; but I am exceedingly jealous of myself, lest I should endeavour to have that done for him as my brother which the Committee might not like to do for him as a tradesman, and it is this which makes me very shy of saying a word about the matter."

During these years Faraday was getting through a vast quantity of work, his experimental researches in electricity were taking up a great part of his time, but other matters were not neglected. He was frequently lecturing before the Royal Institution or the Royal Society; while he wrote a large number of scientific papers for the various philosophical periodicals to which he contributed. Besides presenting series after series of his brilliant Experimental Researches to the Royal Society, he had also to attend to his lectures at Woolwich, and his work for the Trinity House. He must indeed, hard-working man that he was, have found his long day very fully occupied; and it is scarcely to be wondered at that in 1839 the strain began to tell upon him, and a period of rest became necessary. As years went on, such periods of rest were more frequent and yet more vitally important.

In 1837 the British Association[8] held its Annual Meeting at Liverpool, and Faraday attended it, and was made, as he put it, "a most responsible person," President of the Chemical section. From Liverpool he wrote home to his wife, "To-day I think we made our section rather more interesting than was expected, and to-morrow I expect will be good also. In the afternoon Daniell and I took a quiet walk; in the evening he dined with me here. We have been since to a grand conversazione at the Town Hall, and I have now returned to my room to talk with you as the pleasantest and happiest thing I can do. Nothing rests me so much as communion with you. I feel it even now as I write; and I catch myself saying the words aloud as I write them, as if you were within hearing. Dear girl, think of me till Saturday evening. I find I can get home very well by that time; so you may expect me.

"Ever, my dear Sarah, your affectionate husband,

"M. Faraday."

This reference to getting home on Saturday evening is especially interesting, for Faraday always took his wife home to her father's house every Saturday evening, that she might see her family; they all went to church together on the Sunday. This was an unvarying rule of Faraday's for very many years, as long, indeed, as it was possible.

Faraday's mother, after having lived to see "her Michael" come to be one of the great men of his time, died at Islington in March, 1838. The loss must have been keenly felt by Faraday, for between mother and son the tenderest affection had always subsisted. She was justly proud of the position which her boy had won for himself; and he ever retained that beautiful chivalrous kindness and deference to his mother that had characterised him all along. The passages from his earlier letters to his mother which have been given in previous pages are evidence of this, and his kindly consideration was ever the same. Much as the death of his mother, and, a few years later, of his brother Robert, affected him, Faraday had in his beautiful clear-sighted faith in his religion a source of inextinguishable solace, and looking forward to a reunion hereafter could see a "beautiful and consoling influence in the midst of all these troubles."

Severe and long-continued mental work, as I have said, began to tell upon Faraday in 1839, and he was ordered by his doctor to take an absolute rest. He suffered from loss of memory and similar symptoms of an overworked brain. His wife, as her niece tells us, used to carry him off to Brighton, or somewhere down into the country for a few days when he became dull and low-spirited, and the rest soon restored him. During such a sojourn at Brighton, towards the close of 1839, Professor Brande wrote to him, saying that the doctor said Faraday was to remain thoroughly idle for a time; and he (Brande) kindly offered at the same time to do anything he could to relieve Faraday of any routine work. He had indeed read some of Faraday's electricity lectures at the Institution, although, as he terms it in his letter to Faraday, "he began to fear the fate of Phæton in the chariot of Phœbus." As yet, however, Faraday would not take a very long-continued rest, and he was before long back in Albemarle Street working, although less than he had been doing.

In the year 1840 Faraday's health made it necessary that his scientific labours should be reduced, and just about this time, although he was still adding to his series of Experimental Researches, he was husbanding his strength as far as possible. This year, too, deserves especial note, for it was now that he became an elder in the Sandemanian Church; he had before on some occasions exhorted those present at week-day meetings, but it now devolved upon him to deliver regular sermons. Faraday, as we have already seen, on more than one occasion, was not a man to undertake anything without doing it to the best of his abilities; and if this was his character in matters of everyday concern, how much more so should we expect it to be, and not without reason, his character in so vital a question as that concerning his religion. Or perhaps it would be more correct to say concerning the more obvious exercise of his religious faith, for the spirit of his religion coloured all that he did; it was indeed the moving force of his soul, and was not confined to any narrow circle.

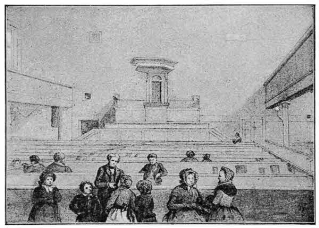

INTERIOR OF THE OLD SANDEMANIAN MEETING-HOUSE, PAUL'S ALLEY.

The flow and energy which characterised Faraday as a lecturer were replaced in his sermons by a simplicity and earnestness that together are best described as true devoutness. His sermons were always extemporary, although the outlines of them were carefully prepared beforehand, a small card having noted down on either side of it the heads of the elder's discourse and reference to such passages in the Bible as he wanted to quote. One of these cards is given that it may show with what slight notes the earnest and reverent preacher provided himself. A friend, describing him officiating at the chapel, which was situated in Paul's Alley, Redcross Street, City, but which has long since been pulled down, and the Church transferred to Barnsbury Grove, N., said, "He read a long portion of one of the Gospels slowly, reverently, and with such an intelligent and sympathising appreciation of the meaning, that I thought I had never before heard so excellent a reader."

|

|

— | 2 Peter iii. 1, 2, 14. A prophetic warning to Christians. |

|

|

— | First, the power and grace and promises of the gospel. |

— | i. 3, by His power are given great and precious promises, |

— | 4, divine nature and brethren exhorted to give diligence, |

— | 5, whilst in this life up to v. 8. |

|

|

— | Then cometh a warning of the state into which they may |

— | fall, 8, 9, if they forget—as he stirs them up, 12, 13, 15, as |

— | escapers from the corruption, i. 4. |

|

|

— | iii. 14. Wherefore, beloved, seeing ye LOOK for such things, |

— | their hope and expectation—it is to stir up their pure mind, |

— | iii., 1, by way of remembrance—hastening the day of the, |

— | v. 12, awful as that day will be, 12, 7, because of the |

— | deliverance from the plague of our own heart. |

— | 2 Cor. iv. 18, 17, 16, look not at things seen—temporal. |

— | Titus ii. 13, looking for the hope and glorious appearing. |

— | Heb. x. 37, yet a little while, and He that shall come will come. |

— | The world make His forbearance a plea to forget Him or |

— | deny Him. |

— | iii. 4, 5, perceiving Him not in His works. His people see |

— | His mercy and long-suffering and look for His promise, 12, |

— | 14, and salvation, 15, and learn that He knoweth how to |

— | reserve, ii 3, 9, and preserve, hence |

|

|

— | they are not to be slothful, Prov. xxiv. 30. |

— | nor sleeping—Matt xxv. 1. Sleeping virgins |

— | nor doubting iii. 4. |

— | nor repining Heb. xii. 12, 3, 5, lift up hands |

— | Jas. v. 7, 8, be patient—husbandmen |

— | waiteth, but waiting, Luke xii. 36, 37, 39, 40, |

— | Peter 41, v. 58, 58 refers to days of long-suffering. |

|

|

— | Wherefore, beloved, seeing ye know these things, beware, etc., |

— | danger of falling away in many parts, i. 9, ii. 20, 21, 22, |

— | great pride of the formal adherers, ii. 19, 13. |

— | But the assurance is at iii. 18—i. 2, 8. |

|

|

COPY OF ONE OF THE CARDS FROM WHICH FARADAY PREACHED.

Another of his listeners said, "His object seemed to be to make the most use of the words of Scripture, and to make as little of his own words as he could. Hence a stranger was struck first by the number and rapidity of his references to texts in the Old and New Testaments, and secondly, by the devoutness of his manner." Yet another friend, who had been privileged to hear Faraday preach before his small flock, said of his sermons, "They struck me as resembling a mosaic work of texts. At first you could hardly understand their juxtaposition and relationship; but as the well-chosen pieces were filled in by degrees their congruity and fitness became developed, and at last an amazing sense of the power and beauty of the whole filled one's thoughts at the close of the discourse."

This, his first period of eldership in the Church, continued from 1840 until 1844, when a slight misunderstanding having arisen between himself and the brethren, he for a time relinquished the office; occupying it again, however, later on in life. His earnest religious feeling was an abiding source of consolation to him in all his trials; it affected in no slight degree his life and life-work at all points, although, to his credit be it said, that it was rather the spirit of his religious feeling which was thus manifested, and it is not by any means to be understood that he was in even the slightest degree given to cant, such a thing being far from possible with him. His religion was a something too sacred and too immediately between himself and his God, as he said, for him to refer to it, except when circumstances especially called for it. Then, in the earnest sympathetic words of comfort, which he addressed to those persons with whom he was intimate when they were in trouble, we may trace the true deep current of religion, which was so essentially a part of his nature.

It is interesting to connect the name of our philosopher with a great institution such as the establishment of the penny post. In 1840 Sir Rowland Hill tells us in his autobiography that he was sorely puzzled to find an ink that, having obliterated the postage stamps, should not be removable. "In my anxiety," he says, "I went so far as to trouble the greatest chemist of the age. Kindly giving me the needful attention, though in an extremely depressed state of health, the result of excessive labour, a fact, of course, unknown to me when I made the application, Mr. Faraday approved of the course which I submitted to him: viz., that an aqueous ink should be used both for the stamp and for obliteration."

Referring to this same year we find an interesting entry in Crabb Robinson's Diary. "May 8th.—Attended Carlyle's second lecture.... It gave great satisfaction, for it had uncommon thoughts and was delivered with unusual animation.... In the evening heard a lecture by Faraday. What a contrast to Carlyle! A perfect experimentalist, with an intellect so clear! Within his sphere, un uomo compito. How great would that man be who could be as wise on Mind and its relations as Faraday is on Matter!"

Faraday's life as a scientific experimentalist and discoverer is divided into two periods by an interval of four years, during which he did but little, or, compared with his previous performances but little, work. Such a time of rest was indeed rendered absolutely necessary by loss of memory and giddiness, which had troubled him occasionally before, and which now put a stop to his experiments. This period of partial rest commenced with a three months' trip in Switzerland, where he was accompanied by his wife and her brother. Dr. Bence Jones says, "In different ways he showed much of his character during this period of rest. The journal he kept of his Swiss tour is an image of himself. It was written with excessive neatness, and it had the different mountain flowers which he gathered in his walks fixed in it as few but Faraday himself could have fixed them. His letters are free from the slightest sign of mental disease. His only illness was overwork, and his only remedy was rest."

A few passages from this Swiss journal are all that can be given. The first stay of any length was made at Thun, whence many walking excursions were undertaken, sometimes indeed Faraday walking as much as forty-five miles in the one day, a sufficient proof that he was not at all bodily ill. The journal gives us many a word-picture of the scenery and of the people, with now and then quaint observations and humorous reflections; let the following passages speak for themselves:—

"July 18th.—Took a long walk to the valley called the Simmenthal, which goes off from the valley of the lake.... The frogs were very beautiful, lively, vocal, and intelligent, and not at all fearful. The butterflies, too, became familiar friends with me, as I sat under the trees on the river's bank. It is wonderful how much intelligence all these animals show when they are treated kindly and quietly; when, in fact, they are treated as having their right and part in creation, instead of being frightened, oppressed, and destroyed.

"Monday, 19th.—Very fine day; walk with dear Sarah on the lake side to Oberhofen, through the beautiful vineyards; very busy were the women and men in trimming the vines, stripping off leaves and tendrils from fruit-bearing branches. The churchyard was beautiful, and the simplicity of the little remembrance posts set upon the graves very pleasant. One who had been too poor to put up an engraved brass plate, or even a painted board, had written with ink on paper the birth and death of the being whose remains were below, and this had been fastened to a board and mounted on the top of a stick at the head of the grave, the paper being protected by a little edge and roof. Such was the simple remembrance; but nature had added her pathos, for under the shelter by the writing a caterpillar had fastened itself and passed into its death-like state of chrysalis; and having ultimately assumed its final state it had winged its way from the spot, and had left the corpse-like relics behind. How old and how beautiful is this figure of the resurrection! Surely it can never appear before our eyes without touching the thoughts.

"Tuesday, 27th.—More pleasant rambles: fine. Now we shall think of a move, and really the changing character of the table d'hôte and other things make me in love with the thoughts of home. Dear England, dear home! Dear friends! I long to be in and among them all; and where can I expect to be more happy, or better off in anything? Dear home, dear friends, what is all this moving, and bustle, and whirl, and change worth compared to you?

"August 2nd.—Interlaken.... The Jungfrau has been occasionally remarkably fine: in the morning particularly, covered with tiers of clouds, whilst the snow between them was beautifully distinct; and in the evening showing a beautiful series of tints from the base to the summit, according to the proportion of light on the different parts. At one time the summit was beautifully bathed in golden light, whilst the middle part was quite blue, and the snow of its peculiar blue-green colour in the clefts.... Clout-nail making goes on here rather considerably, and is a very neat and pretty operation to observe. I love a smith's shop, and anything relating to a smithy. My father was a smith."

How beautiful is the following description of the waterfall at Brienz Lake: "The sun shone brightly, and the rainbows seen from various points were very beautiful. One at the bottom of a fine but furious fall was very pleasant. There it remained motionless, whilst the gusts and clouds of spray swept furiously across its place, and were dashed against the rock. It looked like a spirit strong in faith and steadfast in the storm of passions sweeping across it; and though it might fade and revive, still it held on to the rock as in hope, and giving hope, and the very drops which in the whirlwind of their fury seemed as if they would carry all away were made to revive it and give it greater beauty."

At length, on September 29th, the small party reach London again, and Faraday's journal ends thus:—"Crossing the new London Bridge street we saw M.'s pleasant face, and shook hands; and though we separated in a moment or two, still we feel and know we are where we ought to be—at home."

Faraday's allusion to his father in the extract above is very pleasing and interesting. We are told that he used to like to pay visits to the scenes of his boyhood and youth, and that he once went to the shop where his father had formerly been employed as a blacksmith, and asked to be allowed to look over the place. When he got to a part of the premises at which there was an opening into the lower workshop, he stopped and said, "I very nearly lost my life there once. I was playing in the upper room at pitching halfpence into a pint pot close by this hole, and having succeeded at a certain distance, I stepped back to try my fortune further off, forgetting the aperture, and down I fell; and if it had not been that my father was working over an anvil fixed just below, I should have fallen on it, broken my back, and probably killed myself. As it was, my father's back just saved mine."

On his return from his Swiss trip, Faraday took up a great part of his work again, and was fully occupied with a few electrical experiments, lectures, and Trinity House work. What has been termed his second great period of research did not commence until 1845. He lectured frequently at the Institution—so frequently indeed that we cannot refer to them here, but must leave them to the chapter on his lectures. Indeed, merely to detail the work which Faraday did would take up considerably more than the whole space of this little book.

In 1844 Faraday became one of the special commissioners appointed to investigate the Haswell colliery explosion. In 1846 his brother Robert met with a fatal accident, and Faraday writes to his wife, who was staying at Tunbridge Wells:—"Dear Heart,—.... Come home, dear. Come and join in the sympathy and comfort needed by many.... My sister and her children have not forgotten the hope in which they were joined together with my dear Robert, and I see its beautiful and consoling influence in the midst of all these troubles. I and you, though joined in the same trouble, have part in the same hope. Come home, dearest.

"Your affectionate husband,

"M. Faraday."

In 1849 he delivered his famous lectures on "The Chemical History of a Candle;" and in the following year he gave a series of six lectures on "Some Points of Domestic Chemical Philosophy—a Fire, a Candle, a Lamp, a Chimney, a Kettle, Ashes." His work during these years is shown in his many published letters, in his correspondence which for years he maintained with many of the leading scientists, not only in England but abroad—with De la Rive, Liebig, Humboldt, etc. His work, however, cannot be particularised, neither can the many honours that year after year were awarded to him. We find that he was a man nearly sixty years of age, in the front rank of the great chemists of his country, and acknowledged as such on every hand, and yet we find that he was still the same energetic and enthusiastic scientist, the same kindly and unselfish friend, the same honest and disinterested man that we have seen him all through. Such, indeed, he continued until the very last, his character but "deepening"—as he said of his love for his wife—as the years passed by. His chivalrous deference to women of all ages and ranks was also a remarkable feature of his character, no less at this later part of his life, than when he was a younger man; his chivalry has, indeed, been often referred to, but it was, I learn from Miss Barnard, one of his most readily observed good qualities.