DISTANCE

Distance is a continually shifting relationship, depending on the speed, agility and control of both fighters. It is a constant, rapid shifting of ground, seeking the slightest closing which will greatly increase the chances of hitting the opponent.

![]()

The maintenance of proper fighting distance has a decisive effect on the outcome of the fight—acquire the habit!

![]()

There must be close synchronization between closing and opening distance and the various actions of the hands and feet. To fight for any length of time within distance is safe only if you overwhelmingly outclass your opponent in speed and agility.

![]()

When taking the guard, it is preferable to fall back a little too far than to come too close to your opponent. No matter how fast you are able to parry, if a man is close enough to you he will arrive with his attack, for the nature of an attack is such that it gives the advantage of the initiation to the attacker (providing the correct measure is there). Likewise, however accurate, fast, economical and timely your attack may be, it will fall short unless you have calculated your distance well.

![]()

The fighting measure is the distance which a fighter keeps in relation to his opponent. It is such that he cannot be hit unless his opponent lunges fully at him.

![]()

It is essential that each man learn his own fighting measure. This means in a fight he must allow for the relative agility and speed of himself and his opponent. That is, he should consistently stay out of distance in the sense that his opponent cannot reach him with a simple punch, but not so far that, with a short advance, he cannot regain the distance and be able to reach his opponent with his own powerful attack.

![]()

If fighters are constantly on the move when fighting, it is because they are trying to make their opponent misjudge his distance while being well aware of their own.

![]()

Thus, a fighter is constantly gaining and breaking ground in his effort to obtain the distance which suits him best. Develop the reflex of always maintaining a correct measure. Instinctive distance pacing is of utmost importance.

![]()

The shielded fighter always keeps himself just out of distance of the opponent’s attack and waits for his opportunity to close the distance himself or to steal a march on the opponent’s advance. Attack on the opponent’s advance or change of distance toward you. Back him to a wall to cut off his retreat or retreat yourself to draw an advance.

![]()

The majority of fencers, when they are preparing an attack or trying to avoid one, take turns advancing and retreating. This procedure is not advisable in fighting because the advance and retreat during the assault must be made rapidly, by bounds and at irregular intervals in such a fashion that the adversary does not notice the action until it is too late. The opponent should be lulled, then the attack should be launched as suddenly as possible, accommodating itself to the automatic movements (including the possible retreat) of the opponent.

![]()

The art of successful kicking and hitting is the art of correct distance judging. An attack should be aimed at the distance where the opponent will be when he realizes he is being attacked and not at the distance prior to the attack. The slightest error can render the attack harmless.

![]()

An attack will rarely succeed unless you can lodge yourself at the correct distance at the moment it is launched. A parry is most likely to succeed if it can be made just as the opponent is at the end of his lunge. Many a chance to riposte is missed by the defender stepping back completely out of distance when he parries. To these examples must be added the obvious importance of choosing the correct measure, as well as timing and cadence, when making a counterattack by stop-hit or time-hit.

![]()

Marcelli, past master of fencing, said, “The question whether it is necessary to know in advance the tempo or the distance is a matter for the philosopher rather than the swordsman to decide. Just the same, it is certain that the combatant has to observe simultaneously both the tempo and the distance. And he has to comply with both simultaneously, with the action, if he wishes to reach his object.”

![]()

The fighting measure is also governed by the amount of target to be protected (i.e.: the targets the adversary stresses) and the parts of the body which are most easily within the adversary’s reach. The shin is most vulnerable and is constantly threatened. If the opponent specializes in shin/knee kicking, you have to take his measure from shin to shin.

![]()

When the correct distance is attained, the attack should be carried through with an instantaneous burst of energy and speed. A fighter who is in a constant state of physical fitness is more apt to get off the mark in a fraction of a second and, therefore, to seize an opportunity without warning.

Distance in Attack

The first principle for fastest contact in attacking from a distance is using the longest to get at the closest.

Examples

In kicking: The leading shin/knee side kick (with a lean)

In striking: The finger jab to eyes

Study the progressive weapons charts.

![]()

The second principle is economical initiation (non-telegraphic). Apply latent motor training to intuition.

![]()

The third principle is correct on-guard position to facilitate freedom of movement (ease). Use the small phasic bent-knee position.

![]()

The fourth principle is constant shifting of footwork to secure the correct measure. Use broken rhythm to confuse the opponent’s distance while controlling one’s own.

![]()

The fifth principle is catching the opponent’s moment of weakness, physically as well as psychologically.

![]()

The sixth principle is correct measure for explosive penetration.

![]()

The seventh principle is quick recovery of appropriate follow ups.

![]()

The “X” principle is courage and decision.

Distance in Defense

The first principle for using distance as a defense is combining sensitive aura with coordinated footwork.

![]()

The second principle is good judgment of the opponent’s length of penetration, a sense for receiving his straightening weapon to borrow the half-beat.

![]()

The third principle is correct on-guard position to facilitate freedom of movement (ease). Use small phasic bent-knee position.

![]()

The fourth principle is the use of controlled balance (in motion) without moving out of position. Study evasiveness.

FOOTWORK

One can only develop an instinctive sense of distance if he is able to move about smoothly and speedily.

![]()

The quality of a man’s technique depends on his footwork, for one cannot use his hands or kicks efficiently until his feet have put him in the desired position. If a man is slow on his feet, he will be slow with his punches and kicks. Mobility and speed of footwork precede speed of kicks and punches.

![]()

Mobility is definitely stressed in Jeet Kune Do because combat is a matter of motion, an operation of finding a target or of avoiding being a target. In this art, there is no nonsense of squatting on a classical horse stance for three long years before moving. This type of unnecessary, strenuous standing is not functional, for it is basically a seeking of firmness in stillness. In Jeet Kune Do, one finds firmness in movement, which is real, easy and alive. Therefore, springiness and alertness of footwork is the theme.

![]()

During sparring, a sparmate is constantly on the move to make his opponent misjudge his distance, while being quite certain of his own. In fact, the length of the step-forward and backward is regulated to that of his opponent. A good man always maintains such a position as to enable him, while keeping just out of range, to be yet near enough to immediately take an opening (ref.: the fighting measure). Thus, at a normal distance, he is able to prevent his opponent from attacking him by his fine sense of distance and timing. As a result, his opponent is then compelled to keep shortening his distance, to come nearer and nearer until he is too near!

![]()

Mobility is vitally important in defense as well, for a moving target is definitely harder to hit and kick. Footwork can and will beat any kick or punch. The more adept a fighter is at footwork, the less does he make use of his arms in avoiding kicks and blows. By means of skillful and timely sidestepping and slipping, he can get clear of almost any kick and punch, thus preserving both of his guns, as well as his balance and energy, for counters.

![]()

Also, by constantly being in small motion, the fighter can initiate a movement much more snappily than from a position. It is not recommended, therefore, that you stay too long on the same spot. Always use short steps to alter the distance between you and your opponent. Vary the length of your step, however, as well as the speed, for added confusion to your opponent.

![]()

Footwork in Jeet Kune Do tends to aim toward simplification with a minimum of movement. Do not get carried away and stand on your toes and dance all over the place like a fancy boxer. Economical footwork not only adds speed but, by moving just enough to evade the opponent’s attack, it commits him fully. The simple idea is to get where you are safe and he isn’t.

![]()

Above all, footwork should be easy and relaxing. The feet are kept at a comfortable distance apart according to the individual, without any strain or awkwardness. By now the reader should see the unrealistic approach of the traditional, classical footwork stances. They are slow and awkward and, to put it plainly, nobody moves like that in a fight! A martial artist is required to shift in any direction at split second notice.

![]()

Moving is used as a means of defense, a means of deception, a means of securing proper distance for attack and a means of conserving energy. The essence of fighting is the art of moving.

![]()

Footwork enables you to break ground and escape punishment, to get out of a tight corner, to allow the heavy slugger to tire himself in his vain attempts to land a devastating punch; it also puts pep into the punch.

![]()

The greatest phase of footwork is the coordination of punching and kicking in motion. Without footwork, the fighter is like artillery that cannot be moved or a policeman in the wrong place at the wrong time.

![]()

The value of a couple of good hands and fast, powerful kicking depends mostly on their being on a well-balanced and quickly movable base. It is essential, therefore, to preserve the balance and poise of the fighting turret carrying your artillery. No matter in what direction or at what speed you move, your aim is to retain the fundamental stance which has been found the most effective for fighting. Let the movable pedestal be as nimble as possible.

![]()

The correct style in fighting is that which, in its absolute naturalness, combines velocity and power of hitting with the soundest defense.

![]()

Good footwork means good balance in action and from this springs hitting power and the ability to avoid punishment. Every movement involves the coordination of hands, feet and brain.

![]()

A fighter should not be flat-footed but should feel the floor with the balls of his feet as though they were strong springs, ready to accelerate or retard his movements as required by changing conditions.

![]()

Use the feet cleverly to maneuver and combine balanced movement with aggression and protection. Above all, keep cool.

1. The foundation is sensitivity of aura.

2. The second is aliveness and naturalness.

3. The third is instinctive pacing (distance and timing).

4. The fourth is correct placement of the body.

5. The fifth is a balanced position at the end.

![]()

Use your own footwork and your opponent’s to your advantage. Note his pattern, if any, of advancing and retreating. Vary the length and speed of your own step.

![]()

The length of the step-forward or backward should be approximately regulated to that of the opponent.

![]()

Variations of measure will make it more difficult for the opponent to time his attacks or preparations. A fighter with a good sense of distance or one who is difficult to reach in launching an attack may often be brought to the desired measure by progressively shortening a series of steps backward or by gaining distance toward him when he lunges (stealing the march).

![]()

The simplest and most fundamental tactic to use on an opponent is to gain just enough distance to facilitate a hit. The idea is to press (advance) a step or so and then fall back (retreat), inviting the opponent to follow. Allow your opponent to advance a step or two and then, at the precise moment he lifts his foot for still another step, you must suddenly lunge forward into his step.

![]()

An opponent difficult to reach may be reached by a series of progressive steps—the first one must be smooth and economical.

![]()

Small and rapid steps are recommended as the only way to keep perfect balance, exact distance and the ability to apply sudden attacks or counterattacks.

![]()

Sure footwork and balance are necessary to be able to advance and retreat in and out of distance with respect to both your own and your opponent’s reach. Knowing when to advance and when to retreat is also knowing when to attack and when to protect.

![]()

A good man steals, creates and changes the vital spatial relations to the confusion of his opponent.

![]()

Practice your footwork with a view to keeping a very correct and precise distance in relation to your opponent and move just enough to accomplish your purpose. Fine distancing will make the opponent strive that much harder, and thus bring him close enough to be subject to efficient counterblows.

![]()

To move at the right time is the foundation of great skill in fighting, not just to move at the right time but also to be in the best position for attack or counter. It means balance, but balance in movement.

![]()

Having your feet in the correct position serves as a pivot for your entire attack. It balances you properly and lends unseen power to your blows, just as it does in sports like baseball where drive and power seem to come up from the legs.

![]()

To maintain balance while constantly shifting body weight is an art few ever acquire.

![]()

Correct placement of your feet will ensure balance and mobility—experiment with yourself. You must feel with your footwork. Rapid and easy footwork is a matter of correct distribution of weight.

![]()

The ideal position of the feet is one that enables you to move quickly in any direction and to be so balanced as to resist blows from all angles. Remember the small phasic bent-knee stance.

The rear heel is raised because:

1. When you punch, you transfer all your weight quickly to your lead leg. This is easier if the rear heel is already slightly raised.

2. When you are punched and have to “give” a bit, you sink down on the rear heel. This acts as a kind of spring and takes the edge out of a punch.

3. It makes the back foot easier to move.

![]()

The rear heel is the piston of the whole fighting machine.

![]()

The feet must always be directly under the body. Any movement of the feet which tends to unbalance the body must be eliminated. The on-guard position is one of perfect body balance and should always be maintained, especially as regards the feet. Wide steps or leg movements which require a constant shift of weight from one leg to the other cannot be used. During this shift of weight, there is a moment when balance is precarious and so renders attack or defense ineffective. Also, the opponent can time your shifting for his attack.

![]()

Short steps while moving ensure balance in attack. Also, the body balance is always maintained so that any offensive or defensive movement required is not limited or impaired as the fighter moves forward, backward or circles his opponent. Thus, it is better to take two medium steps rather than one long one to cover the same distance.

![]()

Variations of measure will make it more difficult for the opponent to time his attacks or preparation.

![]()

Unless there is a tactical reason for acting otherwise, gaining and breaking ground is executed by means of small and rapid steps. A correct distribution of weight on both legs will make for perfect balance, enabling the fighter to get off the mark quickly and easily whenever the measure is right for attacks.

![]()

Lighten the stance so the force of inertia to be overcome will be less. The best way to learn proper footwork is to shadowbox many rounds, giving special attention to becoming light on your feet. Gradually, this way of stepping around will become natural to you and you will do it easily and mechanically without giving it a thought.

![]()

You should operate in the same manner as a graceful ballroom dancer who uses the feet, ankles and calves. He slithers around the floor.

![]()

The accent is on speedy footwork and the tendency toward attack with a step-forward (drill! drill! drill!), often combined with an attack on the hand.

![]()

There are only four moves possible in footwork:

1. Advancing

2. Retreating

3. Circling right

4. Circling left

![]()

However, there are important variations of each, as well as the necessity of coordinating each fundamental movement with punches and kicks. The following are some examples:

The Forward Shuffle

This is a forward advance of the body, without disturbing body balance, which can only be performed through a series of short steps forward. These steps must be so small that the feet are not lifted at all, but slide along the floor. The whole body maintains the fundamental position throughout; this is the key. Once body feel results, combine the step with tools. The body is poised for either a sudden attack or a defensive maneuver. Its primary purpose is to create openings (by the opponent’s defensive reactions) and to draw leads.

The Backward Shuffle

The principle is the same as that of the forward shuffle; do it without disturbing the on-guard position. Remember that both feet are on the floor at all times, permitting balance to be maintained for attack or defense. It is used to draw leads or to draw the opponent off-balance, thus creating openings.

The Quick Advance

Remember that though this is a fast, sudden movement forward, balance must be kept. The body flattens toward the floor rather than leaping into the air. It is not a hop. In all respects, it is the same as a wide step-forward where the rear foot is brought immediately into position. Get the body feel with tools.

The Step-forward and the Step Back

Gaining and breaking ground may be used as a preparation of attack. The step-forward is obviously used to obtain the correct distance for attacking and the step-back can be used to draw the opponent within distance. “Drawing” an opponent usually means drawing out of distance from a lead by swaying back from the hips, or making use of the feet in such a way that the lead will just fall short. Its object is to lure your opponent within reach at a crucial moment, while staying out of reach yourself.

![]()

The step--forward will add speed to the attack when it is combined with a feint (forcing the opponent to commit himself) or a preparation (to tie and close the boundaries). If the step-forward is made with the line of engagement covered, the attacker will be in the best position to deal with a stop-hit launched during this movement.

![]()

The step-back can be used tactically against an opponent who has formed the habit of retiring whenever any feint or other offensive movement is made and is, therefore, very difficult to reach, especially if he is superior in height and length.

![]()

Constant steps forward and back with a carefully regulated length can conceal a player’s intentions and enable him to lodge himself at the ideal distance for an attack, often as the opponent is off-balance.

Circling Right

The right lead leg becomes a movable pivot that wheels the whole body to the right until the correct position is resumed. The first step with the right foot may be as short or as long as necessary—the longer the step, the greater the pivot. The fundamental position must be maintained at all times. The right hand should be carried a little higher than ordinary in readiness for the opponent’s left counter. Moving to the right may be used to nullify an opponent’s right lead hook. It may be used to get into position for left hand counters and it can be used to keep the opponent off-balance. The important things to remember are never step so as to cross the feet, move deliberately and without excess motion.

Circling Left

This is a more precise movement requiring shorter steps. It is used to keep out of range of rear, left hand blows from a right stancer. It also creates good position for the delivery of a hook or jab. It is more difficult but safer than moving to the right and, therefore, should be used more often.

The Step-In/Step-Out

This is the start of an offensive maneuver, often used as a feint in order to build up an opening. The foot movement is always combined with kicking and punching movement. The initial movement (the step-in) is directly in, with the hands held high as if to hit or kick, then out quickly before the opponent can adjust his defense. Lull the opponent with this maneuver, then attack when he is motorset.

The Quick Retreat

This is a fast, fluid, forceful backward movement, allowing further retreat if necessary or a stepping forward to attack if desired.

![]()

If it is necessary to combine a step-back with a parry, it is because one is pressed for time. The parry must, therefore, be made at the beginning of the retreating movement—that is to say, when the rear foot moves.

![]()

When the opponent’s offensive action is a compound one, the correct coordination will be to perform the first parry simultaneously with the movement of the rear foot, and the remaining parry, or parries, simultaneously with the retreating lead foot.

![]()

The step back can be taken first, but this should only be the case when the attack has been prepared with a step-forward and not when the attack has been made with a step-forward.

![]()

To a man with quick footwork and a good lead, the art comes easily enough. It is a continuous process of hit-and-away. As your opponent moves in, you meet him with a defensive hit with the lead and immediately step back; then, as he follows-up, you repeat the process, continually retreating around the ring. As you do so, frequently check yourself in your stride and temporarily stop to meet him with a straight right or left or occasionally both.

![]()

Success in “milling on the retreat” takes good judgment of distance and the ability to stop in your retreat quickly and unexpectedly. The common fault is to deliver your blow while actually on the move instead of properly stopping to do it. Develop great rapidity in passing from defense to attack and then back to defense again.

![]()

Remember, do not attempt to hit while backing away. Your weight has to shift forward. Step back, halt, then hit or learn to shift your body weight momentarily forward while the foot backs up.

![]()

Whether on the offensive or retreating, one should strive to be a confusing and difficult target. One should not move in a straight forward or in a straight backward direction.

![]()

When avoiding or maneuvering your opponent by footwork, keep as near to him as you can for retaliatory purposes. Move lightly, feeling the floor as a springboard, ready to snap in with a punch, kick or a counterpunch or kick.

![]()

To retreat from kicks is to give the adversary room so it is wise, at times, to crowd and smother his preparation and gain time consequently with a stop-hit.

Sidestepping

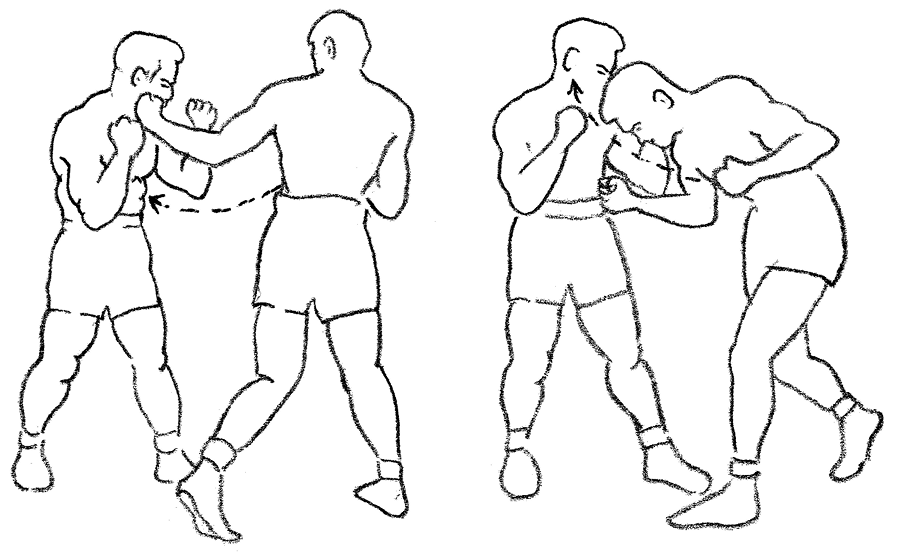

Sidestepping is actually shifting the weight and changing the feet without disturbing balance in an effort to quickly gain a more advantageous position from which to carry the attack. It is used to avoid straight forward rushes and to move quickly out of range. When an opponent rushes you, it is not so much the rush you sidestep as some particular blow he leads during the rush.

![]()

Sidestepping is a safe, sure and valuable defensive tactic. You can use it to frustrate an attack simply by moving every time an opponent gets set to attack or you may use it as a method of avoiding blows or kicks. It may also be used to create openings for a counterattack.

![]()

Sidestepping may be performed by shifting the body forward, which is called a “forward drop.” This is a pretty safe position with the head in close, the hand carried high and ready to strike the opponent’s groin, or stomp on his insteps, or carry a two-fisted hooking attack. The forward drop, also called a “drop shift,” is used to gain either the outside or inside guard position and is, therefore, a very useful technique in infighting or grappling. It is also a vehicle for countering. It requires timing, speed and judgment to properly execute and may be combined with the jab, straight left, left and right hooks.

![]()

The same step may also be performed directly to the right or left or back, depending on the degree of safety needed or the plan of action.

![]()

Properly used, sidestepping is not only one of the prettiest moves, but is also a method of escaping all kinds of attacks and countering an opponent when he least expects it. The art of sidestepping, as of ducking and slipping, is to move late and quick. You wait until your opponent’s kick or blow is almost on you and then take a quick step either to the right or left.

![]()

In nearly all cases, you move first the foot nearest the direction you intend to go in. In order to do the step-in the quickest possible manner, the body should sway over in the direction you are going slightly before the step is made. The rear foot then follows quickly and naturally and, in sidestepping a rush, the fighter turns immediately and counters his man as he flies past him.

![]()

When sidestepping a lead, the counter is naturally quite easy. Not so after a rush for to counter effectively here, a fighter has to keep very close to his opponent, moving just enough to make him miss. The fighter must then turn extraordinarily quickly to be on him before he has flashed past.

![]()

Remember, when an opponent rushes you, it is not so much the rush you sidestep as some particular kick or blow he leads during the rush; indeed, if you step to the side of your opponent without catching sight of some blow to get outside of, you will be very liable to run into a hook or a swing.

![]()

Sidestepping right: Carry the right lead foot sharply to the right and forward, a distance of about 18 inches. Bring up the left foot an equal distance behind the right. The step serves to swing the body to the left, bringing the right side farther forward and closer to the opponent’s left rear (when in a right stance himself). For that reason, the right side step is not used as frequently as the one to the left. Most of the weaving and sidestepping is to the left, keeping you closer to his right and farther away from his left rear hand. (The situation changes in right-stancer versus left-stancer.)

![]()

Occasionally, a right side step is taken just to vary the direction of the weaving and, even less frequently in, slipping a right lead, getting inside of it to counter with a left. It is used in starting a left to the body.

![]()

Sidestepping left: From the fundamental right stance position, bring the left foot sharply to the left and forward a distance of about 18 inches. This should carry you to the outside of the opponent’s right jab. You will find just as you take the step to the left, the left side of your body swings forward and the right side back, so that you rotate toward the opponent’s right flank. As you complete this half-circle movement, you will find that your right foot is again in its normal position ahead of the left foot.

![]()

If you have taken the sidestep to the left to avoid the opponent’s right lead, you should sway your body and duck your head (without losing balance) in the direction of the step—that is to the far left. His right will swish by, over your head, in the direction of your right shoulder. Now, as you wheel to the right toward the opponent, you have his whole right flank exposed and can quickly land a left to the body or jaw with telling effect.

Remember this simple thought: Move first the foot closest to the direction you wish to go in. In other words, if you wish to sidestep to the left, move the left foot first and vice versa. Also, in all hand techniques, the hand moves first, before the foot. When foot techniques are used, of course, move the foot first, before the hand.

![]()

Remember also to always retain the fundamental stance. No matter what you do with that moving pedestal, the turret carrying the artillery must remain well-poised, a constant threat to your foe. Aim always to move fluidly but retain the relative position of the two feet.

![]()

Examine footwork for:

1. Body feel and control, as a whole, in neutralness.

2. Attack and defense capability at all times.

3. Ease and comfort in every direction.

4. Application of efficient leverage during all phases of movement.

5. Superb balancing at all times.

6. Elusiveness in well-protected corresponding structure and correct distancing.

![]()

Experiment on the following mechanics and feeling of footwork:

1. Footwork to be evasive and soft if the opponent is rushing.

2. Footwork to avoid contact point (as if the opponent is armed with a knife.)

![]()

The ultimate aim is still to obtain the brim of the fire line on the opponent’s final real thrusts.

![]()

Remember, mobility and rapidity of footwork and speed of execution are primary qualities. Practice footwork and more footwork.

![]()

Footwork can be gained also by skipping rope (an exercise to learn how to handle one’s body weight lightly), sparring (the learning of distance and timing in footwork) and shadow kickboxing (homework for sparring).

![]()

Running will also strengthen the legs to supply boundless energy for efficient operation.

![]()

Increase control of the legs through medium squatting posture exercises and ape-imitation movement (low walking).

![]()

Incorporate alternate leg splits for flexibility.

![]()

No matter how simple the strokes being practiced in the lesson are or whether they are of an offensive or defensive nature, the practitioner must be made to combine footwork with them. He must be made to advance or retire before, while and after the stroke he is working on has been executed. In this way, he will acquire a natural sense of distance and develop great mobility.

![]()

Practice footwork variations along with:

1. kicking tools

2. hand tools

3. covered hand and/or knee positions

EVASIVENESS

During fighting, there is a good deal of parrying, especially with the rear hand, but it is better to use footwork—duck and counter, snap back and return, slip and punch.

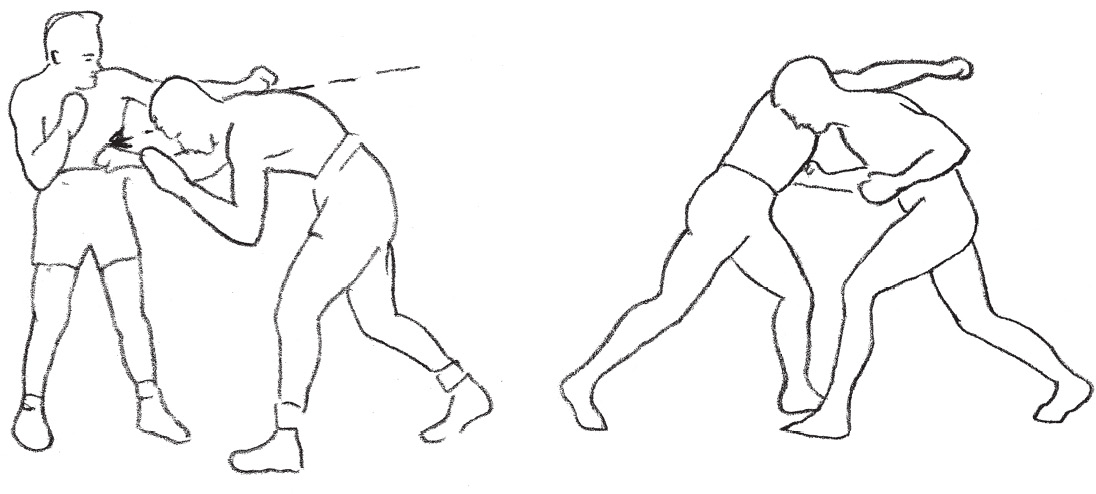

Slipping

Slipping is avoiding a blow without actually moving the body out of range. It is used primarily against straight leads and counters. It calls for exact timing and judgment and, to be effective, it must be executed so that the blow is escaped only by the smallest fraction.

![]()

It is possible to slip either a left or a right lead. Actually, slipping is more often used on the forward hand lead because it is safer. The outside slip, that is, dropping to a position outside the opponent’s left or right lead, is safest and leaves the opponent unable to defend against a counterattack.

Slipping is a most valuable technique, leaving both hands free to counter. It is the real basis of counter-fighting and is performed by the expert.

![]()

Slipping inside a left lead: As the opponent leads a straight left, drop your weight back to your rear left leg by quickly turning your right shoulder and body to the left. Your left foot remains stationary but your right shoulder pivots inward. This movement allows his left hand to slip over your right shoulder as you obtain the inside guard position.

Slipping outside a left lead: As the opponent leads a straight left, shift your weight right and forward over your right leg, swinging your left shoulder forward. The blow will slip over your left shoulder. A short step-forward and to the right with your right foot facilitates the movement. Your hands should be carried high in a guard position.

Slipping inside a right lead: As the opponent leads a right punch, shift your weight over your lead right leg, thus moving your body slightly to the right and forward. Bring your left shoulder quickly forward. In doing so, the punch will slip over your left shoulder. Be sure to rotate your left hip inward and bend your left knee slightly. The inside position is the preferred position for attack. Move your head separately only if the slip is too narrow.

![]()

Slipping outside a right lead: As the opponent leads a right, drop your weight back on your left leg and quickly turn your right shoulder and body to the right. Your right foot remains stationary and your left toe pivots inward. The punch will slip harmlessly by. Drop your right hand slightly, but hold it ready to drive an uppercut to the opponent’s body. Your left hand should be held high, near your right shoulder, ready to counter to his chin.

![]()

Another method is to shift your weight to your left leg and pivot your right heel outward so that your right shoulder and your body turn to the left. Drop your right hand slightly and keep your left hand high, near your right shoulder.

![]()

When slipping, the shoulder roll will shift your head—don’t tilt it unnaturally.

![]()

Try to always hit on the slip, particularly when moving forward. You can hit harder when stepping inside a punch than when you block and counter or parry and counter.

![]()

The key to successful slipping often lies in a little movement of the heel. For example, if it is desired to slip a lead to the right so that it passes over your left shoulder, your left heel should be lifted and twisted outward. Transferring your weight to your right foot and twisting your shoulders will set you up nicely to counter.

![]()

To slip a lead over your right shoulder with a defensive movement to the left, your right heel should be twisted in similar fashion. Your weight is thus shifted to your left foot and your left shoulder is to the rear, so you are favorably placed to counter with a right hook.

![]()

If you remember that the shoulder over which you desire to slip a blow and the heel to be twisted are one and the same, you will not go far wrong. Exceptions are movements similar to the first description of “slipping outside a right lead.”

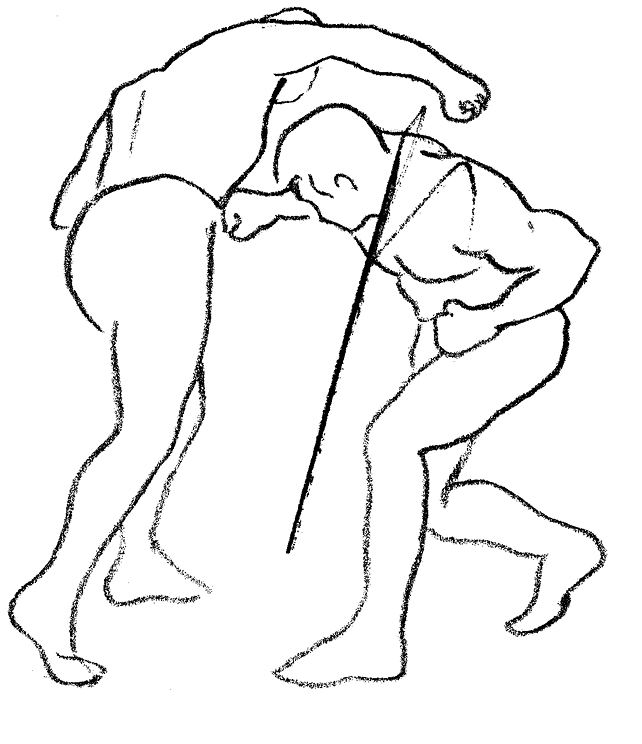

Ducking

Ducking is dropping the body forward under swings and hooks (hands or feet) directed at the head. It is executed primarily from the waist. Ducking is used as a means of escaping blows and allowing the fighter to remain in range for a counterattack. It is just as necessary to learn to duck swings and hooks as it is to slip straight punches. Both are important in counterattacks.

The Snap Back

The snap back means simply to snap the body away from a straight lead enough to make the opponent miss. As the opponent’s arm relaxes to his body, it is possible to move in with a stiff counter. This is a very effective technique against a lead jab and may also be used as the basis of the one-two combination blow.

Rolling

Rolling nullifies the force of a blow by moving the body with it.

• Against a straight blow, the movement is backward.

• Against hooks, the movement is to either side.

• Against uppercuts, it is backward and away.

• Against hammers, it is a circular movement down to either side.

![]()

The Sliding Roll

The fundamental asset of the clever fighter is the sliding roll. He spots the punch or a high kick coming, perhaps instinctively, and takes one step back, sweeping his head back and underneath. He is now in a position to come up with several handy blows or kicks into nice openings.

![]()

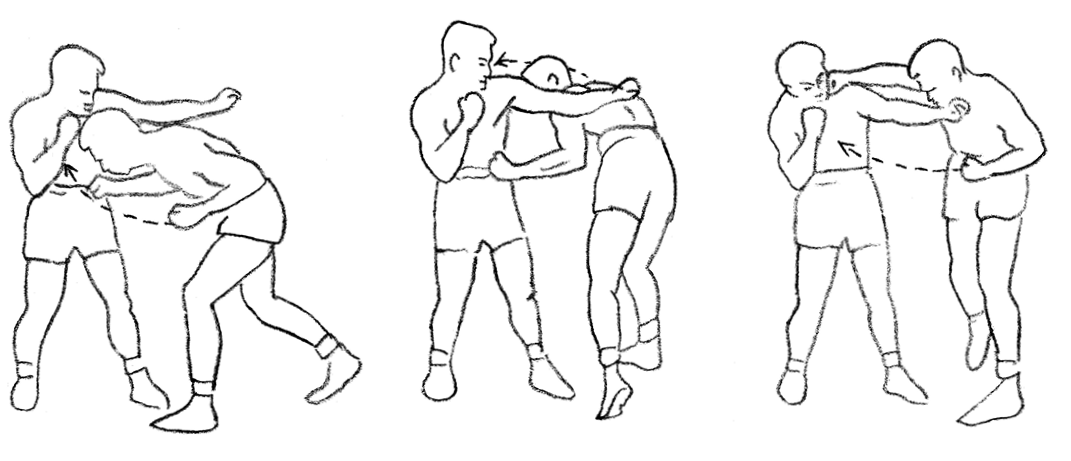

The Body Sway (Bob and Weave)

The art of swaying renders the fighter more difficult to hit and gives him more power, particularly with the hook. It is useful in that it leaves the hands open for attack, improving the defense and providing opportunities to hit hard when openings occur.

![]()

The key to swaying is relaxation and the stiff, rigid type of boxer must be easier to deal with than the ever-swaying type.

![]()

Weaving means moving the body in, out and around a straight lead to the head. It is used to make an opponent miss and to sustain a counterattack with both hands. Weaving is based on slipping and is a circular movement of the upper trunk and head, right or left.

![]()

Mechanics of the bob:

1. Sink under the swing or hook with a single, perfectly controlled movement.

2. Bring your fists in toward your opponent for guarding or attacking.

3. Maintain a nearly normal punching position with your legs and feet, even at the bottom of the bob. Use your knees to provide the motion.

4. Maintain at all times the normal slipping position of your head and shoulders for defense against straight punches. It is extremely important that you be in position to slip at any stage of the bob.

5. Don’t counter on a straight-down bob except, perhaps, with a straight thrust to the groin. Weave to apply delayed counters with whirling straight punches or hooks.

![]()

Purposes of the weave:

1. To make a moving target of your head (from side to side).

2. To make your opponent uncertain about which way you will slip if he punches at you.

3. To make your opponent uncertain about which fist you will throw when you punch.

![]()

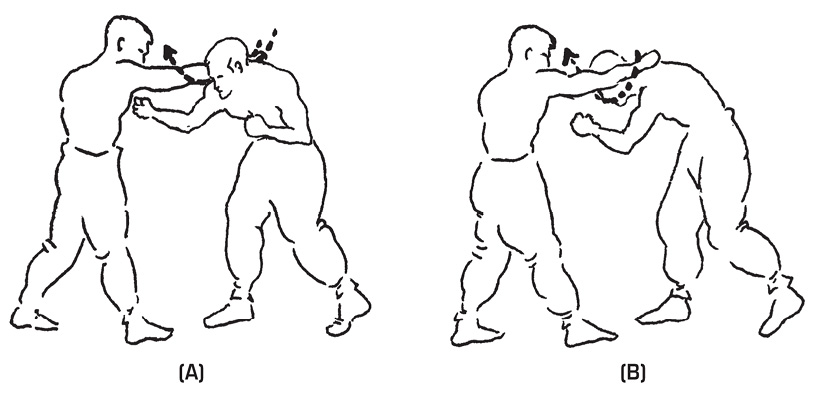

Weaving to the inside: On a right lead, slip to the outside position (figure A). Drop your head and upper body, move in under the extended right lead and then up to the basic position. The opponent’s right lead now approximates your left shoulder (figure B). Carry your hands high and close to your body. As your body moves to the inside position, place your open right hand on the opponent’s left. Later, counter with a right blow on the slip, then a left and right as the weave is performed.

![]()

Weaving to the outside: As the opponent leads a right punch, slip to the inside position (figure B) and place your right hand on the opponent’s left. Now, move your head and body to the left and upward in a circular movement so that the opponent’s right lead approximates your right shoulder. Your body is now on the outside of the opponent’s lead and in the basic position (figure A). Carry both hands high and close.

![]()

Remember, weaving is based on slipping and thus, mastery of slipping helps to obtain skill in weaving. It is more difficult than slipping, but a very effective defense maneuver once perfected.

![]()

The weave is rarely used by itself. Almost invariably, the weave is used with the bob. The purpose of the bob and weave is to slide under the opponent’s attack and get to close-quarters. The real bobber-weaver is always a hooking specialist. It is the perfect attack for one to use against taller opponents. Break your rhythm often when you use it. Don’t be a rhythmatic bobber-weaver. Sometimes when you slip inside a punch, you counter terrifically as you step. Evasiveness should not be practiced without hitting or kicking to counter.

![]()

In addition, while the punches are coming, keep your eyes open every minute. The punches will not wait for you. They will strike unexpectedly and, unless you are trained well enough to spot them, they will be hard to stop.

![]()

The elbows and forearms are used for protection against body punches. Blows aimed at the head are swept aside by the hand when you are not sliding and countering.

Almost every fighter at one time or another reaches a dangerous spot where he loses some of his command and must protect himself. When this time comes, it is wise to have learned good defense.