ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Although writing a book seems to be largely about long periods of time spent alone with a computer, it is ultimately a collaborative effort. In that spirit, I'd like to begin by thanking my best collaborators, Adair Lara and Wendy Lichtman, teachers who became writing partners and then friends, and who have been with this memoir since the very first words I set on paper. Also, thanks to Rebecca Koffman, who has read every version of these pages.

To Richard Reinhardt, who encouraged me to attend the Squaw Valley Community of Writers, where I learned how to write this book. And to both Richard and his wife, Joan, for the use of The Cabin and The Vineyard, truly charmed places in which to write.

Thanks to Meg, for her encouragement and love. And to Kurt, for liking all my endings, especially the ones with hats.

To Jim and Tracy, for the dinners, the babysitting, and the friendship.

I would also like to thank my wonderful agent, Amy Rennert, for her good advice, and for coping with the many neuroses of a writer with a first book. Thanks to my editor, Diane Higgins, for loving this story, and to her assistants, Patricia Fernandez and Nichole Argyres, for handling all the details turning it into a book required.

Thank you to Elaine Petrocelli and the staff and teachers at

vi Acknowledgments

Book Passage for providing so much inspiration and support. They are some of the best friends a writer could have.

Finally, this book would not exist without my husband, Ken, my best editor and best friend, who never stopped believing that we would bring Alex home, and never stopped believing in me.

For Ken,

who gave me the time and space in which to write

And for Alex,

without whom there would be no story

Matryoshka

My son Alex, who is two years old, loves to play with the ma-tryoshka dolls my husband and I bought from a vendor in Iz-mailovsky Park. Each doll is a different family member, and Alex likes to twist open the father, who is playing an accordion, to find the mother nested inside. One by one, he opens them all: the grandfather balancing a yellow balalaika on his knee, the grandmother holding a golden samovar, until he comes to a tiny baby with a red pacifier painted into its mouth.

When he's got them apart, purple and green and black half-bodies scattered across the carpet, I'm struck by how complete the family is: children, mother, father, grandparents. No one is missing, pulled out of place by death or desertion.

As I watch him stacking the dolls, one smiling face disappearing into the round body of another, I have a strong and sudden urge to call my mother. I want to ask her if it's normal for children to eat what the cat threw up, or learn to say "dog" before "Mommy." I want to know if she ever wished I'd get tired of One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish, if she thought about leaving me in the frozen-food aisle when I started to scream and kick the shopping cart, if she lay awake at night, afraid something might take me from her.

Instead, I ask Alex if he wants to play naked tiger, which is what we do to get him ready for his bath. He yanks on the tabs of his diaper and removes it with a grand gesture, a magician

6 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

delighted with the reappearance of his penis. I throw his toys into the tub, while behind me, he leaps around with the white bucket from his training potty on his head. His legs are starting to look more like a boy's than a baby's, and I want to catch them and kiss them while he'll still let me.

I put Alex into the warm water of the tub and push back his hair with a wet hand. With his hair slicked back, he looks like a small, smooth-skinned businessman.

After his bath, I dress him in a T-shirt printed with circus animals.

"Elephant big-nose," he tells me, pointing to an elephant balanced on a ball.

We jump onto the bed together, the weight of our bodies pressing a valley into the comforter. Alex slips the first two fingers of his right hand into his mouth, fingers that have developed small calluses from rubbing against the sharp edges of his teeth. He presses his damp head against my chest, wetting my shirt and raising goose bumps. I tuck my knees beneath his legs, so more of his body touches mine, and remember another bed.

The pink chenille spread that left curved tracks on my cheek if I rested on it too long, the stripy light from Venetian blinds that clanged like something mechanical whenever the wind blew, and my mother, sleepy and pregnant with my twin brothers. Every afternoon we'd nap together, with my face as close to hers as she would allow. Before we'd fall asleep, I'd ask her to sing the same song over and over—a song in Italian about an orchestra.

Lying on her back, my yet-to-be-born brothers causing the middle of her body to rise like a mountain, my mother would pretend to play the trombone, her arm pulling the long slide up toward the ceiling. Turning to look at me, she'd purse lips with traces of pink lipstick on them and make the wet sound of a trumpet. Just her breath on my face made me feel as if nothing bad could touch me.

Now, in the bed with Alex, I try to sing the Italian song about the orchestra, but only a few of the words come back to me. The rest I have to invent: long phrases filled with vowels that make Alex smile around the fingers in his mouth.

Lying there, I wish I could ask my mother if she can still slide the trombone to the ceiling, still make the wet sound of the trumpet. I wish I could ask her if she would breathe on my face again.

Alex's biological mother abandoned him in a Moscow hospital three days after he was born. She left without telling anyone, disappearing back to the Ukraine, leaving the orphanage to find a name for him. Because it was still winter, they chose for his last name the Russian word for snow.

Alex was the result of his mother's third pregnancy. Ken and I do not know whether he has a brother like the boy matryoshka who plays a flute painted around the curve of his head, or a sister like the matryoshka who carries a single spotted teacup. We don't know if his mother ever had the babies from those pregnancies, or why she chose to have him.

Alex loves the mother matryoshka. Sometimes he opens up the set just to her. Her painted dress is embroidered with puffy white sleeves, and she has round blue eyes and blond hair. She looks much more like him than I do.

One day, I imagine that he will look at her small painted-on mouth and ask her the questions about his Russian mother that I cannot answer.

Alex throws his body over the footboard of the bed to show me how he can stand on his head. His hair falls into the air like ruffled feathers.

Then we go into his room, and I sit on the floor beside a dress-up frog whose clothes I can no longer find. Alex puts the matiyoshkas back together, starting with the baby with the painted pacifier in its mouth, which he threatens to eat because he likes it when I tell him not to. When he's finished, he comes

8 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

and sits in my lap, nesting himself there. I push my nose into the skin at the back of his neck, breathing in the scent of rising bread, and vanilla bean, and the ocean. And I wonder if my mother had ever breathed in the scent of my skin, and if she thought it as sweet.

ww>

Cellular Multiplication and Division

I never wanted to have children.

I'd watch the families climbing out of their minivans and walk wide around them, so I wouldn't be contaminated by the damp stickiness of their parenthood. I'd study them from afar, little girls with princess hair and socks that matched their dresses; moms lumpy from pockets filled with goldfish crackers and Cheerios. The dads always seemed confused, lugging a crying child in a plastic carrier like something heavy someone else had slipped into their basket at the supermarket.

The lives of these parents appeared to be made up of running noses, earnest cartoon characters, and small plastic cars to be stepped on with bare feet. Watching them move across the parking lot, the mother unaware of the small chocolate-colored handprint on the seat of her pants, the father dragging a flowered diaper bag behind him, I'd shudder and walk cleanly away, a neat leather purse over my shoulder.

And then my mother started dying.

My mother's cancer came as a small hard lump in her breast. She discovered it one morning in the shower and told her doctor before she told anyone else. She had to wait a week for the mammogram. Another to see the surgeon. She said she could feel the cancer cells spreading through her body as the receptionist turned the pages of her appointment book.

When the surgeon did see her, he put her in the hospital and removed the hard lump the size of a BB that wasn't supposed

14 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

to be there. Afterward, I flew from my home in California to New Jersey to see her.

"It's in the lymph nodes," she said. She was sitting up in bed, dressed in a hospital gown with green geometric shapes printed on it. She wasn't smoking, and it made her look strangely still. "All I get is bad news."

They kept her in the hospital for five days. The night before she was released, she told me, "Tomorrow, we'll go to the outlets."

"You're sure?"

"Yes. I want to go to Lizzie's." Lizzie's was the Liz Claiborne outlet. My mother kept on a first-name basis with all of her favorite stores.

By 10:00 the next morning, we were walking among clapboard buildings with false dormers meant to make the mall resemble a small New England village. By noon, we'd made two trips back to the car to unload shopping bags. By 3:00, the arm where the surgeon had removed my mother's lymph nodes was so sore, she could try on only slacks and shoes.

The following week, I drove her to her first appointment with the radiologist. While we waited, I pointed out the purplish highlights in the receptionist's hair, the outfits of celebrities in People magazine, hoping these things would keep my mother from noticing the sallow-skinned people waiting beside us.

After half an hour, the purple-haired receptionist called my mother's name, and a technician tattooed the place on her breast where they would aim the radiation.

The next day, my mother told me to go home.

"I'll be fine," she said. My parents were divorced, my mother now married to man who was younger than she was. "Mike will take care of me."

After the radiation, my mother was given chemotherapy. Every three weeks she'd lie in a reclining chair while drugs that destroyed every fast-growing cell in her body dripped into her

veins. Her last treatment came the week before Thanksgiving. My husband, Ken, and I flew back to spend the holiday with her.

We sat in her living room surrounded by my mother's collection of antique clocks—clocks that chimed the hour several minutes apart, so that I always felt that time itself was forced to wait until the last clock had caught up. My mother's scalp was covered with soft down like a baby duck's, and she'd lost the thick black eyebrows that made her look like herself. Her skin had a greenish cast, made greener by the pale pink lipstick she liked to wear.

"It was hell," she told us. "I don't care what happens, I'm never going through that again."

But two years later, when the cancer metastasized to her liver, she agreed to try an experimental high-dose chemotherapy.

When my mother's cancer returned, undeterred by the radiation and chemicals the rest of her body couldn't tolerate, I began to believe that I would be next. At least once a week, I'd check my own breasts, lying flat on the floor because I thought it would make it easier to detect the lump I knew was hiding under my skin like a small time bomb. Moving my fingers in the tight spiral shape I'd learned from the "Guide to Breast Self-Exam" enclosed in a package of panty hose, I'd hold my breath until I'd reached the last spiral.

"I'm thinking about having a mastectomy," I told my mother on the phone.

"Whatever for?" she asked.

"I'm afraid this is going to happen to me."

"I did not give you breast cancer," she said, and hung up.

Not long after, I stood in line at the supermarket behind a woman with boxes of apple juice and a little boy in her cart. As the woman waited for the cashier to ring up shampoo that wouldn't cause tears and packages of fruit leather, she ran her fingers up and down the back of the boy's Winnie-the-Pooh sweatshirt. I watched her brush the fuzzed fabric and thought

16 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

that her life must be filled with the touch of soft things: flannel pajamas and stuffed bears, well-washed blankets and the little boy's skin. Running my fingers along the sleeve of my sweater, I tried to imagine what that would be like.

As my mother lost the ability to walk—from the cancer or the chemotherapy, nobody seemed to know which—I began to wonder what it would feel like to be pregnant. I imagined myself huge and round, so fertile I could make fruit and flowers spring out of the ground just by walking over it. Pregnancy seemed the antithesis of cancer; another condition that caused cells to multiply and divide, but with an entirely opposite result.

When the experimental chemotherapy did not slow the cancer in my mother's liver, I called and told her I wanted to visit.

"This isn't a good time," she said. "The house is a mess. I've got a woman here taking care of me. There's really no room for you."

And I let her talk me out of coming, afraid that if I saw her I would have to tell her about wanting a baby.

The one time I'd gotten pregnant, my mother had slapped my face. I was twenty-one years old and had forgotten to use my diaphragm.

"We could get married," my boyfriend told me. He was thirty-three and had been married before.

"I don't think so," I said, not realizing until he'd asked that I didn't want to marry him. "Besides, I don't want children."

On a bright morning, he drove me to a clinic near the Bronx Zoo, where they performed so many abortions the preop counseling was done in groups of five.

Two weeks later, I woke in the middle of the night with stomach cramps and threw up on the floor.

It took nearly two months for the doctors to discover that I was still pregnant, the fetus trapped inside one of my fallopian tubes, rupturing it every time it tried to grow. They put me in the hospital two days before Christmas and scheduled me for surgery.

The night before the operation, a fireman dressed as Santa Claus came into my room and gave me a candy cane and a handful of Hershey's kisses. Later, the doctor came by to explain that he would have to remove the damaged tube.

"As long as you're in there," I told him, "tie the other one."

The doctor stared at me, sucking on the chocolate kiss I'd given him.

"I'm not planning on having children. Ever."

"That's not a decision you should make right now."

And when the surgery was over, I still had one untied tube.

After the operation, I moved back into my old bedroom. I told my mother I'd had the surgery to remove a cyst.

A few weeks later, a bill from the anesthesiologist arrived and she opened it. At the bottom of the page, under diagnosis, someone had typed "tubal pregnancy." My mother read the words and slapped my face. She said it was for not telling her the surgery had been so complicated, for not letting her know that I might have died. I told her people rarely died from having a fallopian tube removed, but she only looked as if she wanted to slap me again.

"I'm so glad you don't want to have children," my mother would say after that. "It's too risky for you." And I didn't argue with her, though I knew that women who'd had tubal pregnancies also had babies every day.

While my mother waited to hear if she'd be a candidate for a bone-marrow transplant, I sent her small gifts. Bath oil scented with lavender, a wooden roller etched with tight grooves to massage her feet, books on tape with stories where nobody died. One day, I sent her a tape about cancer patients who had cured themselves using meditation. It was called, "How to Be an Exceptional Patient."

"Why did you send this to me?" my mother shouted into the phone. "I don't want to be an exceptional patient, I want to be left alone." And she hung up before I could say anything.

The only time my mother had ever walked me to school was

18 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

the first day of kindergarten. I remember shiny black plastic shoes reflecting red and yellow leaves, a pear in a brown paper bag with my name printed on it, the feel of her bigger hand wrapped around mine. When school was over, I ran outside, searching for her among the mothers standing outside the chain-link fence.

"It's only two blocks," she said, when I got home, my plastic shoes already cracking across the toes. "You know the way."

The summer I was ten, my father would take my brothers and me waterskiing on a small lake that smelled of oil and gas from the boat engines. We were each allowed to bring a friend, and every Saturday, six kids and my tall black-haired father would take turns skiing until our legs felt shaky and we'd swallowed so much lake water that it hurt to take a deep breath.

My mother never came with us on those Saturdays. "A whole day on a boat with a bunch of kids?" she'd say, taking a pack of cigarettes and an instant iced tea out to a lounge chair in the backyard. "No, thanks." And she'd look at my father as though his wanting to spend the day with us revealed something embarrassing about him.

I remember hearing my mother once say that she wished she'd never had children, but when I asked her about it, she sounded surprised.

"That's impossible," she said, lighting a long, thin cigarette. "I couldn't wait for you to be born." And then she repeated the story she told me every year on my birthday.

"When I went to the hospital to have you, it was still winter. The trees were bare and there was snow on the ground."

"In April?" I asked, because that was what I always asked.

"Yes. But the day I left the hospital to bring you home, the flowers were blooming and the birds were singing. It was like you'd brought spring with you."

After a while, my mother stopped talking about the bone-marrow transplant. I knew she was on antidepressants, and there

must have been something else for the pain. Sometimes she'd fall asleep while I was talking to her, and the woman who was staying at her house would have to hang up the phone.

Again I made plans to visit.

"Ken and I are going to Boston on business," I told her. "We'll come to see you as soon as we're finished."

She drifted back into sleep before she could tell me not to come.

While we were in Boston, my brother called to tell me that my mother had died. When I told Ken, he held me in his arms and cried into the back of my neck. I could see his shoulders moving up and down.

There were no flights to New York until the next morning. In the meantime, I needed to be around noise and people, so Ken and I walked to Boston's North End, to the Italian neighborhood. It was the last night of a feast dedicated to a Catholic saint—I didn't know which one, and the hot, rainy streets were jammed with tourists and locals. Men in white V-necked T-shirts carried a plaster statue of the saint, dipping him so the faithful could pin dollar bills to his ribbon sash.

There were sausages sizzling at stands on every corner, and somebody had set a pair of speakers in their second-floor window—Frank Sinatra singing "Fly Me to the Moon." I knew these things were there, the smell of meat cooking, the syrupy sound of Frank Sinatra's voice, but it was like observing them through water.

I don't have a mother anymore, I repeated to myself, as Italian women with fleshy arms reached past me to embrace friends in the crowd. And I wondered when I would cry.

Ken and I walked by booths featuring games of chance— roulette wheels where the money lost would benefit the church—past stands filled with pyramids of sugarcoated zeppoles shiny with oil.

"We should eat," I told Ken. And we pushed into a tiny

20 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

restaurant where a neon sign blinked: "We are famous for our mussels."

We sat at a small table, our knees touching beneath the red and white checked cloth.

"Mussels," we told the waitress, unable to disobey the sign.

The mussels came served in a cast-iron skillet that burned my wrist when I touched it to the edge. We washed them down with wine that stained our teeth purple.

I tried thinking about the time my mother had hit me with a can of frozen orange juice and broken a blood vessel beneath my eye. The six months we didn't speak to each other after she made me leave the house.

Instead, I remembered the Easter I was thirteen and my best friend and I were to sing a duet in the church choir. We'd practiced for weeks, our voices high and pure—just like angels, I'd thought. But on Easter morning, as we stood surrounded by white lilies, the hymn about Jesus rolling away the stone suddenly seemed unbearably funny, and we started giggling.

The organist began the music over again, giving us a chance to catch up, but we couldn't stop laughing long enough to get out any of the words about the washing away of our sins. My Sunday-school teacher hissed at us from behind the organ, and I was certain that my mother would be furious. But when I spotted her in the second row, her face was buried in the Easter-morning program, and the top of her head was shaking with laughter.

In the restaurant famous for its mussels, a man wearing a plastic lobster bib pretended to catch his little girl's finger with a red claw as his wife showed their son how to twirl spaghetti in a soup spoon.

My mother is gone, I thought, watching the woman lick sauce off the little boy's nose.

"I've been thinking about having a baby," I told Ken.

He held a mussel shell shaped like a small boat in the air.

"You said you never wanted children."

"But you always did."

He took a drink of the wine. His tongue looked purple.

"I could never imagine not having them."

"Did you think I'd change my mind?"

"I hoped you would."

I watched the father in the plastic bib wiggle the front half of a lobster in his little girl's face.

"It might not happen right away. I have only one fallopian tube, and I'm almost forty."

"We could start tonight." Ken showed me his purple tongue.

"Not tonight." I didn't want to start a baby in all that sadness.

Instead, we ordered another bottle of purple wine, and as the pile of mussel shells grew between us, we talked about whether crooked teeth were hereditary, and spoke aloud every name we had ever loved.

The Urine of Postmenopausal Nuns

The first time I tried to get pregnant was in a small hotel on the coast of Maine, shortly after my mother's funeral. It was an old-fashioned New England place with croquet on the lawn and a boathouse where you could sip gin and tonic and watch the other guests in outfits from L. L. Bean rowing on the bay.

Our room had a small window with starched white curtains that blew in on a wind smelling of salt water and boiled lobster. Ken and I made love on scratchy sheets, and afterward I lay listening to the wooden rowboats bumping against the pilings, wondering if I was pregnant.

When I wasn't, I bought a copy of Our Bodies, Ourselves: Updated and Expanded for the Nineties. It still had the illustrations I remembered from college: diagrams of female genitalia, and line drawings of couples engaged in sexual intercourse. The women were always sketched with unshaven armpits. They were nearly always shown on top of the men.

Thumbing through, I found forty-nine pages devoted to preventing pregnancy, nothing about encouraging it.

However, a section on natural birth control gave elaborate instructions on how to use changes in body temperature and vaginal mucus to determine when you were most fertile. I decided to practice this natural method, charting the rise and fall of my fertility, and then have sex whenever I wasn't supposed to.

I spent the next few months making a graph of my daily temperature and checking the viscosity of my vaginal mucus.

24 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

But my temperature graph never seemed to make any of the little spikes the book described, and no matter how I rolled and pressed it between my fingers, my vaginal mucus always felt exactly the same.

"Stay in bed with your legs and hips elevated for thirty minutes after sex," said a woman who was having her hair shampooed next to me.

And the next time Ken and I made love, I lifted my feet high on the wall behind our bed and lay there like a biblical vessel waiting to receive the gift of life.

"Could you bring me a glass of water?" I asked Ken. "Can I have another pillow?"

While I waited, I visualized thousands of tiny sperm swimming up my vaginal canal like little salmon.

"Your uterus is probably out of balance," said my friend who believed in the healing power of crystals and the advice of psychics. "Let me align it for you."

I took off my clothes and crawled onto her massage table. My friend lit votive candles, placing them on every flat surface. Then she put on music sung by a woman with a high breathy voice.

I closed my eyes, and the friend who listened to psychics rubbed sandalwood oil in little circles around my navel, working her way out to the edges of my pelvis, as if she could see what lay beneath the skin with her fingertips. When my breathing became deep and slow, she placed her fingers near my hipbones and pressed, fast and hard. It felt as if everything inside me had been rearranged.

"You should get one of those ovulation predictor kits," suggested a pregnant woman in my yoga class.

There were eight different brands on the drugstore shelf. I chose the one with the baby on the box.

I put the box with the baby on it in my medicine cabinet and tried not to think about it too much. Buying the ovulation predictor meant that Ken and I had made the leap from people

who were going to get pregnant right away to people who weren't—a distance we'd been covering in baby steps each month when I'd get my period.

"I have to pick up some tampons," I'd tell Ken, as if what I was saying had little importance. "Do we have any Advil?" And I wouldn't look at him, afraid that seeing his disappointment would make mine more real, the way looking through a magnifying glass makes everything appear bigger and more sharp.

I began measuring my life in two-week increments. When I got my period, I'd just want the two weeks until I ovulated again to be over. Once I ovulated, I wanted to fast-forward to the day I'd written the P in my calendar, to find out if I was pregnant.

Each month, when my breasts felt heavy and sore, I'd think, I'm pregnant. I'd lie in bed and convince myself I was nauseated, focusing my attention deep in my belly, certain I could feel a soft fluttering there. I'd turn down a glass of wine without saying why and imagine my baby growing ever more perfect.

And then, when I felt the warm blood slide out of me, I'd be sorry I ever made myself want this. I'd wish I could go back to pitying the pregnant women in their tentlike dresses with little collars that made them look like gigantic schoolgirls. I hated envying their swollen bellies and feet, their need for naps and glasses of milk.

"My sister-in-law had a friend who got pregnant after trying acupuncture," the checker at the drugstore told me.

The acupuncturist's office smelled like the shops in Chinatown, the ones that sold ginseng roots shaped like little men.

"Stick out your tongue," the acupuncturist said, and I made a face like a Balinese mask while he stared into my mouth. Then he placed four fingers along a tendon in my arm and concentrated so deeply that I was afraid to breathe.

"Take off your shoes and socks and lie on the table," he instructed.

I heard him opening small paper sleeves, and when I turned

26 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

my head I saw him slip a short needle into the skin of my wrist. The needle didn't hurt; it didn't feel like anything. Only the sound of the paper sleeves being torn let me know he was putting in another.

Afterward, the acupuncturist gave me a small plastic bag filled with a fine gray powder that had the same bitter, musty smell as the room.

"Mix two teaspoons of this with hot water, and drink it three times a day."

I drank it all, even though it tasted like dirt.

"Isn't it funny how you get pregnant only when you don't want to?" my chiropractor asked, twisting my neck so it made a burst of popping sounds. "Like when you're in high school and it'll ruin your life?"

"I want to have sex in the car and pretend we're seventeen years old," I told Ken.

"No problem," he said.

We made love in our Toyota Celica, parked in our own driveway, twenty feet from our bed.

"Can you move just a little?" I asked Ken. "My head keeps bumping against the button that makes the window go up and down.

"Try taking a vacation," my dental hygienist advised from behind her plastic mask. "I know loads of people who have gotten pregnant on vacation."

Ken and I went to Mexico and made love on a lumpy bed in a town where dogs barked all night. At an open-air market, I found an old man who sold potions and remedies. His stall was crowded with old shoeboxes filled with powders, dried herbs, and plants I'd never seen before.

"Do you have anything that might help someone get pregnant?" I asked him, making my hands emulate the curve of a pregnant belly. The woman selling chipotles in the next booth turned away, smiling.

The man handed me a round black root still covered with dirt. :h chocolate," he said. He mimed shaving a piece off the root.

"Why chocolate?*" I asked.

Again, he made the little shaving motion. "This," he said, pointing to the root; then another shaving motion. "And chocolate."

Ken took the root from me, turning it over in his hand.

"What is this?" he asked the man.

The man shrugged, and said something in Spanish to the woman in the chipotle booth. They both laughed.

1 brought the root home, hiding it in my suitcase from the agricultural inspectors at the airport.

j re not going to eat that, are you?" Ken said. course not." I told him.

I put the root in my underwear drawer, along with a Cadbury Fruit and Nut bar and a vegetable peeler.

The next morning, while Ken was in the shower, I shaved off a piece of the black root and a piece of the Cadbury bar. I put the two pieces together, black and brown curls, and smelled them. Chocolate and earth. I heard Ken turn off the water, step out of the shower, and I put the shavings on my tongue. Bitter and sweet, they tasted. I swallowed them.

When the black root from Mexico did not make me pregnant, I called a fertility clinic.

"How long have you been trying?" asked the woman who answered the phone.

:een months. Eighteen cycles of my period." That's long enough."

She explained all the treatments I could try: hormones that would make me produce more eggs, a procedure that involved ng Kens sperm before injecting it into me. Which would be most likely to get me pregnant?"

28 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

"We have the most success with in vitro fertilization."

"That's what I want."

Everything in the clinic's waiting room was baby-colored: pink walls and pale blue carpeting. Another couple sat across from Ken and me on a mint green couch. They were holding hands and laughing about something in the clinic's copy of Business Week. I'd heard that only 25 percent of the couples who tried in vitro got pregnant—one in four—and I worried that the laughing couple would get our baby.

A woman in a pale blue lab coat that matched the carpet came into the waiting room. "I'll be your in vitro fertilization counselor," she told Ken and me. "I'll be taking you step-by-step through what can often be a difficult and complicated process."

"Thank you." I leaped off the couch and reached for her hand. "Thanks so much."

The in vitro counselor led us into a small office with photographs of snowcapped mountains on the wall. She sat behind an empty desk and smiled. Her teeth were very white, like the snow in the pictures. Extending her baby blue arms, she handed us each a little book titled The In Vitro Fertilization Story.

"The first thing we're going to do is put you on birth-control pills."

"But I want to get pregnant."

"The birth-control pills are to regulate your cycle, so it coincides with your in vitro appointment."

"Couldn't I just change my appointment?"

"These appointments are given out months in advance." She stretched out the word "months." "They cannot be changed at the last minute."

"Yes, yes, of course," I assured her. "I wouldn't do that."

"Good." The counselor showed me her white teeth. "Now, a few weeks before your appointment, we'll start you on injections of Pergonal."

"What's Pergonal?" asked Ken.

"A fertility drug made from the urine of postmenopausal nuns."

Ken laughed through his nose.

"The nuns live in the French Alps," the counselor informed him. She looked pointedly at the snowcapped mountains on the wall, making me believe they must be the home of the postmenopausal nuns.

"The possible side effects of Pergonal include mood swings, severe headaches, and strangulated ovaries."

I gave my head a little nod for each side effect.

"What about cancer?" Ken asked. "Don't fertility drugs cause cancer?"

"Preliminary studies show a possible connection." The counselor studied the cuff of her baby blue sleeve. "But as of this point, nothing concrete has been documented."

Since my mother's death, I'd begun to believe that cancer's having come so close to me had made me more susceptible. I'd hold my breath when I walked past idling cars, wouldn't let the dentist X-ray my teeth, and stepped away from the microwave when it was on. I ate only organic fruits and vegetables, checked my meat and milk for growth hormones, and swallowed so many antioxidants and cancer-fighting vitamins that it took two glasses of nonirradiated orange juice to wash them all down.

Yet now I could sit in a room decorated in baby colors, and ignore everything the counselor was saying about the increased risk of uterine and cervical cancer.

"So there's no documented connection between Pergonal and cancer?" I said.

"Not at this time."

"Good."

"When your eggs are ready, we'll remove them with a long needle that can pierce the uterine wall. And then we'll fertilize them."

30 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

"That's where you come in." The counselor turned to Ken and flashed him her white teeth.

"Once the eggs are fertilized, we'll use a catheter pushed through the cervix to introduce them into your uterus."

I was nodding my head at her like it was attached by a spring.

This is how it should be done, I thought, with piercing needles and catheters filled with fertilized eggs. All this relying on penises and vaginas was much too imprecise.

The counselor stood and excused herself, leaving us alone while she went to get something she called "the financials."

"Are you sure you want to do this?" Ken whispered. His copy of The In Vitro Fertilization Story was open to a drawing of a fallopian tube with a twisted-looking blob at the end of it.

"I want a baby."

"Can't we keep trying on our own?"

"If you want. But we're going to do this, too."

The financials were three pages long. At the bottom of the third page was the total cost of our vitro fertilization. $10,000.

"And we pay this whether we get pregnant or not?" Ken said.

"Of course," the counselor told him.

"Of course," I echoed.

I'd already decided that I would use the money I'd gotten from the sale of my mother's house, an amount that was close to $100,000.

"How many times are you thinking of trying this?" Ken asked me.

"Two or three." But I'd already calculated the number of tries against my mother's money, and knew I'd keep going until I'd used every bit of it.

Grisha

"The people who have successful adoptions are patient, willing to be flexible, and are not easily discouraged," said the woman at the front of the room. She was wearing a baggy sweater and a paper badge that read: "Hello my name is Maggie." Beside her, printed on a flip chart, was the question, "Is Adoption for You?"

I was sitting on my coat and the backs of my legs felt itchy and hot. Ken and I had arrived too late to get a seat at the big table in the center of the room, and we'd had to squeeze into a row of chairs that had been added along the wall.

The room smelled of wet wool and the green powder that the janitors would use to sweep the floors in high school. Someone had written, Gung Hay Fat Cboy, the Chinese for Happy New Year, across the blackboard.

Beneath fluorescent lights, couples close to forty and single women with resolute expressions were writing Maggie's words into notebooks. Ken had handed me a pad when we sat down, but I hadn't gotten any further than the question on the flip chart.

I was three months away from my in vitro appointment.

In the weeks following the orientation at the fertility clinic, I'd started calling adoption agencies I found in the yellow pages.

"Please send me your materials," I'd say. And my mailbox would fill with photographs of adoptable children.

"Would you like to make an appointment?" the bright-voiced women at the other end of the line would ask me.

"Not yet," I'd tell them. "I still have other options."

I'd known only one person who was adopted. She was the daughter of friends of my father's; people who were not related to me by blood, but seemed to be because I'd known them all my life. This adopted girl was tall and dark, and when she stood next to her short, fair parents, she made me think of the object that doesn't belong on an IQ test—the carrot in a row of apples.

Maggie was writing on the flip chart with a marker that left the sharp smell of ink in the room. On one side of the page, she printed the words Domestic Adoption, on the other, International Adoption. Beneath them, she wrote Risks in red ink. Each time she lifted her hand, the sleeve of her sweater slid down her arm.

"Birth mothers are your biggest risk in domestic adoption because they can always change their minds." Maggie printed Birth mother below the red Risks.

"In international adoption, it's the instability of foreign governments." She wrote Political Instability beside Birth mother, and drew little red arrows radiating from the words.

"My agency handles international adoption, mostly children from Russia and former Soviet bloc countries."

Maggie tossed a pile of brochures on the center table.

The woman sitting in front of us turned to pass one to me. I noticed that she kept a hand on her husband's arm, as if to keep him in the room.

Maggie had used a picture of herself on the cover of the brochure; her pale eyes and dull brown hair looking much the same in black and white as they did in person. In the photograph, she was holding the hand of a small boy wearing the kind of hat that's sold at Disneyland: a black beanie with plastic mouse ears. The hat was too big for the boy, and it made him look shrunken and elderly.

Inside the brochure, Maggie described Russia as bleak and degenerating. Delays are to be expected, she wrote. It is not uncommon for adoptions to be stalled or never completed.

I'd heard about this meeting on the radio while driving across

34 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

the Golden Gate Bridge. I'd had to keep repeating the phone number over to myself until I could stop and write it down.

"We should go to this, just to see what our options are," I told Ken.

"But I thought we weren't planning on adopting."

"We're not." I did not tell him that I believed going to an adoption meeting would help me get pregnant, the way that women who adopt suddenly find themselves pregnant.

Maggie turned the flip chart over to a clean page.

"These are the documents you'll need for an international adoption: Certified originals of birth certificates and marriage certificates." She scrawled the words in black ink, putting a little check mark beside each each item. "Notarized financial statements. Copies of federal income-tax returns. Letters of recommendation." She filled the page with check marks like a child drawing a flock of birds.

I watched a nearsighted woman whose glasses reflected so much light that her eyes seemed to float. She was moving her pen quickly across the paper. I could hear it scratching like a small, nervous animal.

"Then there's the paperwork required by the Immigration and Naturalization Service."

Maggie wrote 1-600 Orphan Petition at the top of the paper and started a new list beneath it, writing so fast I couldn't keep up.

"We are never going to have a child," I whispered to Ken.

He smiled as though I'd said it to make him laugh. Then he reached for my leg, but patted my folded coat instead.

Maggie turned back to the page that read "Is Adoption for You?"

The nearsighted woman was nodding her head, as though the question had been asked aloud.

"I just received a tape of Russian orphans." Maggie pointed to a portable television in the corner. "It'll be on in the back of the room."

She snapped the tops back onto her markets, and everyone closed theit notebooks.

The woman in the thick glasses stumbled over a chair rushing to speak to Maggie. I pulled my tights away from the backs of my thighs, and went to watch the videotape.

On the screen, a small blond boy in blue overalls was trying to walk. He took a few heavy-footed steps, and fell face first onto an Oriental carpet. I waited for him to push himself up and try again, but he didn't move. He just lay there, crying into the elaborate pattern of the rug. Behind him, the thick calves of a woman in a white coat moved back and forth, busy with something else.

The woman who'd been holding onto her husband's arm made a little "aww ..." sound.

Ken was looking through a binder of children's photographs. The children in the pictures were dressed in tetry-cloth jumpsuits, and had neat lines in their hair, marking where someone had passed a comb. I watched their small, serious faces appear and disappear as Ken turned the pages.

"Cute," he said without much conviction.

"This is the fourth adoption meeting we've been to," said a man in a leather jacket. "China, South America, Vietnam, now Russia." He ticked the countries off on his fingers.

Ken pushed the binder over to him. "Here."

"Thanks."

Ken touched the man's leather shoulder.

"Let's go," he said to me.

"Single-parent adoption is possible," Maggie was telling the nearsighted woman, "at least for now." The woman leaned in close, trying to focus on each word as it came out of Maggie's mouth. "But all that could change. The Russians are always changing the rules."

"Good night," Ken told her.

I took my umbrella out of a metal wastebasket. It was still wet.

"Thanks." I followed Ken to the door.

36 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

"You know," Maggie said to our backs, "there's a little boy on that tape who could be yours."

We turned around.

"I mean, he looks like you." She stared at me. "Same big, dark eyes."

Ken took a step to where the video was still running. "On that tape?"

"He's the last child."

The nearsighted woman turned her glasses to me, showed me her floating eyes.

My umbrella made a little shh . . . sound as it slid back into the wastebasket.

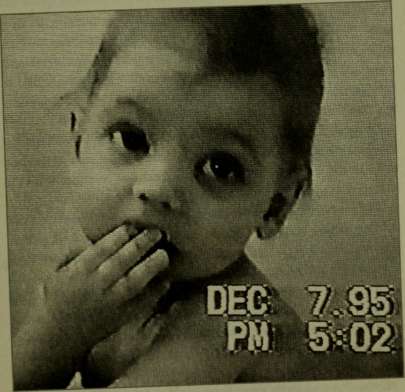

The boy on the videotape had enormous eyes and wispy brown hair that stood up on the top of his head. He was naked, lying on a white metal changing table and kicking his legs out behind him in little swimming motions.

Beside him stood a squat woman with the kind of determined round face that had once appeared in photographs of Russian housewives lined up to buy toilet paper. She was wearing a white lab coat and had tied a babushka around her hair, and it made her look like a cross between a scientist and a charwoman.

In the background, I could hear a man's voice speaking in Russian. He shouted at the woman and she turned the little boy's head toward the camera. His dark eyes stared at me.

A hand in a white sleeve materialized from the side of the screen. It held a yellow-spotted giraffe that squeaked when it was squeezed. The hand crushed the giraffe close to the little boy's ear, and a female voice called, "Grisha! Grisha!"

The man behind the camera barked a command, and the woman in the babushka lifted the boy up. His small hands were clenched into fists, and I could see his ribs, his uncircumcised penis, his too-thin legs.

She's gripping his chest too tightly, I thought, forcing a breath of air into my own lungs.

The woman made a move to set the boy down, and the man behind the camera shouted at her. He seemed unable to decide how he wanted the boy displayed, and the woman swung the small body back and forth like a bell. When at last she lay him belly down on the metal table, he slid the first two fingers of his right hand into his mouth and began sucking them.

The woman shot out a thick arm and pulled the fingers from his mouth.

"Don't do that," I scolded the videotaped woman.

Two hands in white sleeves appeared and began clapping out a rhythm that made me think of Cossacks dancing with crossed arms. The little boy watched the moving hands, curling his upper lip back over three new teeth, and squinting his eyes shut. His flat baby nose was creased, and I supposed he was smiling, because the woman in the babushka smiled back just long enough for me to see a gold incisor.

The camera moved in close to the boy's face, turning his features soft and blurry. The two fingers of his right hand rested near his cheek, on their way back into his mouth, and the odd smile was gone, replaced by a certain vacancy. I could not pull away from the dark eyes Maggie had thought so much like mine, and I felt a pressure in my chest, as though my heart had become too large for the space that contained it.

Ken made a sound like choking, and the little boy disappeared into a blue screen.

"I've got a photo of him somewhere," Maggie said. She searched through a folder stuffed with brochures, pushing aside pictures of her own face. "I took it from the TV."

She pulled out a blurred Polaroid photograph, held it out to me. "You can take it with you."

But I still have other options, I wanted to tell her. I still have the piercing needles and the urine of postmenopausal nuns.

38 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

"Go ahead," she coaxed, waving the Polaroid as if she were drying it.

But Russia is full of political instability. And // is not uncommon for adoptions to be stalled or never completed.

"I can take another one."

I looked down at the small face in her hand, remembered the odd unpracticed smile.

It's only a picture. It doesn't mean anything.

I reached for the photograph and slipped it into the soft wool of my pocket.

"Why don't you try domestic adoption?" asked a woman who was balancing her two-year-old son on her hip. "That's what we did with Paolo." She slipped her hand under the bottom of the little boy's sweater and rubbed his smooth belly.

I ran my finger along the thick edge of the photograph that had spent the past week in my pocket. Below us, thin January sun shone on rows of bare vines that seemed incapable of bursting into leaf.

A woman walking by touched the rounded curve of Paolo's cheek. Another woman asked if there was any more chardonnay.

It was a party of women. My friend Kate hosted it every year in a borrowed house above vineyards. She called the event "No Boys Allowed" and invited mothers and daughters and women she'd only just met but who seemed interesting. Women who'd been arriving since late morning, carrying in winter flowers and pots of soup, blue-veined cheeses, and blood oranges.

"Domestic is so much easier," said Paolo's mother. "You work with a lawyer. You know all about the birth mother." She was keeping track of the advantages on the fingers she'd wrapped around her son's back. "And you get your child younger, so you can bond with him sooner."

The little boy on her hip pulled open the breast pocket of her shirt and looked inside.

"They gave Paolo to me as soon as he was born." She cupped one of the little boy's red basketball sneakers in her hand and jiggled his leg.

"But what if the birth mother changes her mind?"

"That's why you work with a good lawyer. I'll give you the name of mine."

She handed Paolo to me while she searched her pockets. I shifted him to my other side so his weight wouldn't crush the photograph in my pocket.

"Call this number." She traded me the card for her son. "This woman will get you a baby." She blew a dark bang out of Paolo's eye and went to get more wine.

I watched a thirteen-year-old girl and her mother dancing to Aretha Franklin, their winter coats twirling around them. Then I sat at an outdoor table, where women were shaping small figures from blocks of clay.

A speech therapist had made a horse with uneven legs. An actress who sold real estate was just finishing a mermaid with a clamshell bra. Her five-year-old daughter was making a pig.

I sat beside Kate, who was working on a pregnant woman. The little figure had wide hips, swollen breasts, and a rounded belly twice the size of her small clay head.

"It's a fertility goddess," she explained.

Kate had been trying to get pregnant for four years.

"Do you think it'll work?"

"Who knows?" She shrugged. "My mother has me visualizing my baby floating around in my uterus now."

She thwacked a piece of clay in front of me. "Here, make one for yourself."

Kate was the first person who knew I wanted a baby.

It was the summer my mother was dying. Ken and I had gone with Kate and her husband, Dan, to a cabin in the Sierra foothills that had been built in the 1940s by Dan's grandfather. In the afternoons, we'd swim in a green lake that made our teeth chatter

40 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

if we stayed in too long. At night, we'd drink bourbon and play board games we found on the knotty-pine shelves, the clicking of the dice competing with the sound of crickets outside the screens.

Every morning, Kate and I would walk into town for newspapers and doughnuts.

"I'm thinking about having a baby," I told her, halfway between the 7-Eleven and the bakery.

Kate stopped walking and dropped the branch she'd been using to knock the heads off weeds along the side of the road. She was shorter than I, and when she reached up to hug me, the hair on the top of her head tickled my chin.

"I'm so glad we're going to do this together," she said, rubbing my bare shoulder.

Kate added a little more clay to her pregnant woman's belly, using her thumbs to make the mound symmetrical. "I'm going to keep her under the bed."

"I loved being pregnant," the speech therapist said.

"Me, too," agreed the actress. "I felt absolutely and completely sensual."

I pulled small pieces from my block of clay, remembering a book on infertility I'd taken from the library and kept only two days because having it in the house made me think of myself as barren, like Ruth in the Old Testament. The book had suggested holding a little mourning ceremony for the biological child you would never have.

Write a letter to your never-to-be-born baby, the book advised. Print his or her name on a piece of paper and burn it, sending all your hopes and expectations skyward with the smoke.

Pressing my fingers into the wet clay, I wondered if that would work. If burning the name of a nonexistent child would keep me from feeling that I'd been excluded from something, like the boys who were not allowed at this party.

"What are you making?" asked Kate.

I looked at the rounded bits of clay I'd fashioned into small arms and legs, the piece that could be a torso, lying on its belly.

"I'm not sure."

I could attach the clay legs so they looked as if they were about to make the kicking motions from the videotape, thin the body so it would be a more accurate representation, take a pointed stick and draw in the feathery hair. Afterward, I could take the clay figure of the little boy and put it under my bed, and let something other than me decide if this was the way I would become a mother.

"Have you ever thought about adopting?" I asked Kate.

"Oh, Dan and I are pretty far from that. We still want to have our own child."

She used a stick to give her fertility doll a pair of oval-shaped nipples.

"Why? Are you thinking about it?"

"I don't know." I smushed the clay arms and legs together. "I'm terrible at this kind of thing."

In the kitchen, a woman was hovering over a pan of brownies. "My husband's a dentist," she said with her mouth full, "but he's really a poet."

"Are those vegan?" asked another woman, who kept touching the side of the pan.

I wandered into the back bedroom and shut the door. Sitting on the bed, I picked up a knitted doll from Guatemala and walked it across the pillows. Then I dialed my own number.

"Is it just me, or can you not get that little boy out of your head?" I asked Ken.

He breathed into the phone.

"It's not just you."

"What should we do?"

"I could call that woman from the meeting."

"Maggie."

"I could call her."

42 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

"What about the in vitro?"

"I'd love it if you didn't have to go through that."

"But then I don't get to be pregnant."

I sat the Guatemalan doll on my lap and straightened its knitted hat.

"We don't know anything about adoption. We've never even thought about Russia."

"My family came from there," Ken said. "Poland, actually— near the Russian border."

Outside, Paolo's mother was dancing with her son, riding him on a hip and holding his arm up as if they were waltzing.

"Maybe you should call Maggie," I told Ken.

"It's Sunday."

"You can leave her a message."

"OK," he said. "I love you."

"I'm going to hang up now so you can call."

Outside, more women were dancing: Kate and the vegan and the speech therapist who had loved being pregnant. They swirled beneath a papier-mache parrot that hung above the patio.

I reached into my pocket and took out the Polaroid. There never was an unborn child for me to mourn, I thought, never a name to send skyward. There is only this little boy.

I put the photograph back and went to dance with the women beneath the bright bird.

The address Maggie had given us was a small, dark house in the Berkeley hills. It slumped in a grove of peeling eucalyptus trees that made the air smell like Vicks VapoRub.

We ran to the porch through rain that dripped off the sword-shaped leaves of the eucalyptus. Ken knocked on the door, bouncing a crystal that hung behind the window. I unrolled the collar of his jacket where it had bunched up; picked a piece of lint off my corduroy skirt and threw it into the rain.

Maggie opened the door.

"Good," she said, "you're here."

She turned to lead us into the house, and I saw that the seat of her black leggings was covered with cat hair.

"Just let me get something." She stopped at a small room that must have been her office.

The screen of her computer was covered with overlapping Post-Its reminding her to buy cat litter and get gas. She had an old-fashioned fax machine that printed messages on rolls of curled paper, and a long fax had tumbled out of the machine and onto the floor like a paper waterfall.

Maggie searched through the piles of paper on her desk, rearranging them into new configurations. Buried beneath a book about achieving financial freedom, she found a yellow folder covered with the rounded scribbles someone makes when they're testing a pen.

"Why don't we go into the living room?" she said, waggling her fingers at the tiny office. We followed her down a dark hallway that smelled like mushrooms growing.

I sat on the couch, trying not to touch a pillow that looked to be made of some kind of fur. Ken sat beside me, sinking into a cushion so soft it puffed up around his hips.

"I don't know if the little boy you're interested in is still available." Maggie pulled a chair over from her kitchen table.

"What do you mean?" Ken asked.

"Yuri probably sent that tape to all the agencies he works with."

"Yuri?"

"Yuri's my Russian coordinator."

Maggie brushed something off her seat.

"Frankly," she said, "he's a bit of an asshole."

Ken and I stared at her from the depths of the couch.

"Anyway, I sent him an E-mail."

"Can't you call him?" Ken asked.

"I don't know where he is. I only have a number for his wife."

44 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

"What does she say?"

Maggie shrugged. "Who knows? She doesn't speak English."

"You mean there's no way to reach him?" Ken, who wore a pager that vibrated against his side whenever someone wanted him, did not believe in the unreachability of anyone.

Maggie put her face close to us.

"He's hiding from the Russian Mafia," she whispered.

"Mafia?" Ken tried to raise himself out of the billowing cushion.

"They broke into the apartment of a friend of Yuri's—another adoption coordinator." Maggie's face looked overheated. "They burned all his papers and smashed his computer."

"Why?"

"There's money in adoptions." Maggie sat back in her chair.

I touched the furry pillow by accident and wiped my hands on my corduroy skirt.

"Anyway, if it turns out that your child is available, you'll have to travel to Russia right away. Moscow wants families to see their children before they send in their paperwork."

"You mean we see him and then we have to leave him behind in the orphanage?" I couldn't imagine how I would be able to hold that little boy, learn the smell of his skin, and then get back on the plane carrying only a paperback and an inflatable pillow. "Isn't that hard?"

"Everybody does it." Maggie shrugged, but it seemed to me as fantastic as discovering that everybody breathed water or had X-ray vision.

Maggie dug around in the scribbled-on folder, pulling out forms and little notes and shoving them under her thigh for safekeeping.

"Here's a list of all your adoption expenses." She handed me a green paper. "My fee is $5,000." She pressed her finger against the page. "Yuri's is $10,000. A lot of his is used for bribes." Talking about bribes gave her that feverish look again.

"What's this?" Ken asked. "Humanitarian aid, $1,000."

"That's money you pay directly to the orphanage."

"To buy food and things for the children?"

"Sometimes that happens," Maggie said, and I remembered the bones along Grisha's spine, sticking up like a row of small mountains.

Maggie handed me one of the papers from beneath her thigh. "This is a list of the documents you'll need to send to Moscow."

According to the list, the Russians wanted us to be tested for HIV, TB, and the exact amount of albumin in our urine.

"What should we do about the letter from our employer?" Ken asked. "We work for ourselves."

"What do you do?"

"Write comedy."

Maggie frowned and crossed her legs, a couple of papers fluttered to the floor.

"Trade-show scripts," I explained. "Very technical."

"I guess you could just write your own letter," Maggie said, but she didn't sound certain..

Maggie didn't sound certain about a number of things. "They don't need to see your tax returns," she told us, then a little later instructed us to make three—no, four—copies of our 1040s. "I think you'll have to wire over an I-17IH approval form," she said, although when she thought about it, it was possible that they'd changed that requirement. "Everything you send in must be apostilled," she explained, and when we asked her what apostilled meant, she told us it was something they did up in Sacramento which she'd never quite understood.

"How many adoptions have you done?" I asked Maggie.

She scratched at her leggings.

"Three, maybe four."

I waited for her to decide which it was.

"I'm working on one now. A six-year-old girl from Siberia. The orphanage director doesn't want to let her go."

46 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

"Why not?"

"I don't think he likes Americans."

I stared at the arm of the couch where a cat had pulled fibers into a little forest of loops. I needed to make myself believe that Maggie could work the magic necessary to get Grisha out of the orphanage; that she and the man named Yuri she couldn't reach by telephone would be able to wave our documents and money and release him like a dove from a dark-sided box.

"Anyway, this is all we can do until we hear from Yuri." Maggie stood. A yellow Post-It was stuck to the back of her leg.

We followed her back through the damp little house.

"You'll call us as soon as you hear from him?" Ken asked.

"Of course."

"When do you think that'll be?"

Maggie's shoulders moved up in a shrug and stayed there as we went out into the rain.

While we waited for Maggie's call, Ken bought books. Every day he'd come home with a new title: Raising the Adopted Child. Real Parents, Real Children. Are Those Kids Yours?

He'd stack these books beside the bed and read to me from them at night; entire chapters about bonding and attachment, pages on the telltale signs of abandonment grief.

"What if he's not available?" I'd say, turning onto my side and pushing my feet down to where the sheets were cool. "What if somebody else saw him first?"

But Ken would just keep reading, insisting that I listen to the section about the adopted preschooler.

Ken told everybody about Grisha. "He's a little boy from Russia," he explained to his mother on the phone. "Didn't Daddy's family come from there?"

"He sucks his first two fingers," he said to Kate, who'd called to talk to me. "The same ones I did."

"We'll have to go to Moscow," he informed a man from a

software company we were writing a script for. "Probably sometime this month."

"What are you going to tell them if we don't get him?" I'd ask. "What are you going to say?"

But he wouldn't answer me. And later I'd hear him on the phone, explaining to whoever had called that Grisha was the Russian diminutive for Grigori.

"Where should we put his bed?" Ken wanted to know when we were supposed to be working. "Do you think he'll want to sleep with us?"

"I don't know," I told him, trying to concentrate on a brochure with glossy photographs of people smiling at their computer terminals.

But I'd be remembering the swimming motions Grisha had been making on the videotape, imagining the two of us in an ocean as warm as a bath, me holding him across the surface of the water, and him splashing me with drops that would leave my lips as salty as if I'd been kissing away tears.

"Did you call the fertility clinic?" Ken asked me, at least once a day. "Did you cancel the in vitro?"

"I will," I told him. But I kept putting it off.

I couldn't see myself with any of the other children on Maggie's videotape; the dark-haired boy in the saggy diaper who was trying to climb the bars of his crib, the brother and sister with identical faces in different sizes. If the little boy with the inexpert smile couldn't be mine, I wanted my turn with the piercing needles and the urine of the postmenopausal nuns.

It was three days before we heard from Maggie.

"The phone!" Ken shouted. He was wearing a pink towel and his cheeks were covered with a green shaving gel that smelled seaweedy.

"You get it," I said.

He ran past me, still clutching the black handle of his razor.

48 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

"Hello? Hello?" He yelled into the receiver, like someone using a phone for the first time.

I stood in the doorway of the bathroom, wet hair dripping down my neck.

"It's Maggie," Ken mouthed. "She's heard from Yuri."

If I can touch two pieces of wood before she says anything, I thought, nobody else will be taking him. I placed a hand on either side of the doorjamb.

"Yes?" Ken was saying. "Yes?" And then he was nodding his head at me and wiggling his legs in a little dance beneath the pink towel.

I waited in the doorway with my palms touching wood.

"Thank you," Ken said into the phone. "Thanks so much."

He put down the receiver and yanked off the pink towel, twirling it over his head.

"He's ours, he's ours, he's ours!" he sang, dancing around the bed with his penis flapping.

I ran across the room and caught him around the waist. The hair on his chest was springy and damp.

"Let's ask Maggie for a copy of the tape," I said.

"OK."

"And more of those pictures."

"All right."

Ken wrapped his arms around me. The seaweedy gel made our cheeks stick together.

"I think he should sleep with us," I told him. "Don't your books say that's better for bonding? Later, we could put a crib, or maybe a small bed, in the room next to ours, so we can hear if he has a bad dream."

"All right," Ken kept saying into my wet hair. "OK."

Perinatal Encephalopathy

Kate and Dan lived in an old house they'd spent years renovating. Before they'd bought it, the house had come loose from its foundation, torquing itself around an old stone fireplace like a bent back. Kate and Dan had had to raise the entire structure in order to coax the house back into alignment.

Ken and I walked up the stone steps, skipping the one that was loose.

Inside, the house smelled like the Middle Eastern markets Dan was always taking us into; tiny grocery stores where he'd spend an hour poking his nose into jars of spices, before presenting us with little bags of the sweetest cardamom, the hottest clove.

"Dan's making Moroccan lamb stew," Kate said. She stretched up for the wineglasses, her loose sleeves moving a second or two behind her. "He's been simmering it for three days."

"It gives the spices time to get into the meat." Dan hugged Ken and me at the same time, the way an adult can hug two children at once.

"Can I put this on?" Ken waved around the videotape Maggie had given us of Grisha in the orphanage.

"In the living room," Kate said, but he was already gone.

Ken aimed two remote controls at the television like a gun-fighter. Behind him was a photograph he'd taken in Mexico and given to Kate because she'd loved it: twin girls walking along a cobblestone street in white communion dresses, the girl in front examining her lace bib for stains.

"Hey, Dan, which remote is it?"

"The one that says Sony."

"They both say Sony."

Ken pressed a button, and the sound of a woman singing in Portuguese wailed out of speakers that flanked the fireplace like Easter Island statues.

"I love this singer," Dan shouted over the woman's moaning. "She's Brazilian."

Ken pressed the other remote, and Grisha popped up on the television. He seemed to be moving his legs in time to the Brazilian music.

"It's on!"

"Pause it!" I made little motions with an imaginary remote at the television.

Ken pressed a button and silenced the singer from Brazil. Grisha continued moving his legs, as though he could still hear the music.

"The other one," Kate said, touching Ken's shoulder as she went by.

Ken froze Grisha with one leg in the air.

Dan carried in a tray of gold-colored drinks, placing them on a New Yorker magazine that, because of an error in the subscription department, came addressed to Dan & Kate Ryan, Best in Frozen Foods.

"I'm starting it." Ken pressed the remote and Grisha's legs started moving again.

"Grisha! Grisha!" called the off-camera voice.

Dan sat beside Kate on the couch.

"Grisha is the nickname for Grigori," I explained, forgetting that Ken had already told them this.

Dan repeated the name in the accent of a Russian cartoon character.

The babushkaed woman on the television lifted Grisha, displaying his naked body for the camera.

52 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

"Look how long those legs are," Ken said, pointing with the remote. "I think he's going to be tall."

"He will grow strong for to work for the people," Dan said in his Russian cartoon voice.

The arms in the white sleeves appeared, clapping out the music for Russian dancers. Grisha pressed his eyes shut and lifted his lip, in his off-kilter smile.

"I love that," Ken said.

"Hmmm ..." Kate made the sound with her gold-colored drink pressed against her lips.

Dan was still talking in his cartoon voice, referring to the little boy on the tape as "comrade."

Grisha's face blurred, then cleared. He was closer now, his dark eyes staring out of Dan's wide-screen TV.

Kate is going to cry, I thought. And I set my drink on the magazine addressed to Best in Frozen Foods, so I could watch her.

Kate cried at things that were sad, and things that were happy. "Once I cried at the opening of a Kmart," she'd told me. And I'd never once doubted it was true. Every Thanksgiving, we'd gather with Dan's family at the cabin in the Sierras, and after dinner, we'd put on hats that hung from antler pegs—a plaid hunting cap, a rubber rain hat, a turban from a play Dan had been in—and go around the table telling the things we were thankful for. As each person listed his or her particular blessing, Kate would sit in a little felt pumpkin hat and cry.

But now, with Grisha's solemn face wide across her television set, Kate's eyes were narrowed and dry.

I turned back and watched Grisha disappear.

Kate and Dan had told us where Tuscany was and explained why we would want to go there. They'd cooked the first cassoulet I'd ever eaten, the first posole. They'd taught us about the painted animals from Oaxaca, the music of Ben Webster, and how to make ice cream out of fresh peaches.

Every New Year's Eve, the four of us would cook an elaborate

dinner while wearing hats made of shiny paper. On their tenth anniversary, we'd all gone to Mexico, where we spent a week sampling the cocktails Dan invented and fishing out the iguanas that fell into the toilet. Once, to settle a bet, we took turns weighing our heads on an old bathroom scale.

Now Ken and I needed to know what they thought of the little boy kicking his legs in a Russian orphanage.

Ken rewound the tape, making everything on the screen happen backward.

"You can see why we fell in love with him," he said.

Something beeped in the kitchen.

"The stew!" Dan ran out of the room, bumping the photograph of the girls in their communion dresses.

Ken turned to Kate, spilling some of the gold-colored drink on his leg.

"Incredible isn't he?" She was staring at the screen, watching the woman in the babushka push Grisha's fingers back into his mouth. "He's very cute."

"Katie?" Dan poked his head in the room. "Did you remember to put in the tabil?"

"The stuff in the little bowl?" She hopped off the couch, making waves in her drink. "I can't remember." And she followed him into the kitchen.

On the television, Grisha's body was swinging back and forth like a bell in reverse. I watched with Ken for a while, and then went into the kitchen.

The kitchen windows were steamy, the air peppery and damp.

"Smell this." Dan held a small bowl of brown powder under my nose. It was sharp and spicy and burned a little, like breathing in cayenne.

"Every one of my kids wants to be Martin Luther King, Jr.," Kate was saying. Kate taught preschoolers: three- and four-year-olds whom she spoke to in both Spanish and English. "We're doing a play for Martin Luther King Day, and I've got twenty little MLK, Jrs."

54 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

She lifted the lid on a steaming pot of fennel, letting loose the smell of licorice.

"Do you think he's a little thin?" I asked her.

She poked at a fennel bulb with a fork.

"That's to be expected."

"We have to go to Moscow soon to see him."

"You should try to get some Cuban cigars, while you're there." Dan leaned over the fennel pot.

"They want us to make sure we want him."

"That fennel is done."

Then Ken came in and asked Dan a question about the way he'd hooked up his speakers, and Dan went into the other room, saying he wanted Ken to listen to something by a new band made up of musicians from an old band he remembered Ken liking. Kate said the couscous was probably ready and wouldn't be good cold, and Dan opened a bottle of red wine he'd found in a North Berkeley wine shop that reminded him of a meal he and Kate had eaten in Spain. Then we all sat down to dinner, and Ken tried to remember the name of a movie he'd seen in college that he thought took place in Morocco, and Dan told us about a play he was thinking of doing which would require him to learn several accents, though none of them would be Moroccan, and Kate said that North Africa was supposed to be beautiful and we should all try to take a trip there, and somehow the conversation never came back to what it was Kate had or hadn't seen on the videotape.

Kate called the next day.

"I'm giving you the name and number of a specialist in child development. I think you should show her your videotape."

"Why?"

"She'll know if he's doing all the things a nine-month-old should be doing."

"From a tape?"

"You can tell a lot from a tape."

I doodled on the number she'd given me, turning the eight into a little man with a hat.

"You really think I should do this?"

"Just so you know."

I added a pair of running legs to the little man, remembering the boy in the helmet. He was twelve, maybe thirteen years old, and couldn't control his limbs, so that he had to wear a Styro-foam helmet whenever he went out. Now and then, I'd see him with his mother in the grocery store; the mother making one-word exclamations—"Apple!" "Carrot!" "Pear!"—and the son repeating them.

I didn't want to be doing that, I thought. I didn't want to be teaching my teenaged son the names of the most common fruits and vegetables.

"All right," I told Kate, "I'll show her the tape."

"That was heartbreaking," said the specialist in childhood development.

The director who was sitting beside her nodded, her glasses inching down her nose.

The specialist's name was Jill. She had big, bony hands, and when she shook mine, she'd made it look like a child's.

The director's name was Sharon. She was round and hard, like the small European ladies who push you out of their way at the market.

"Could we watch it again?" asked Jill.

Ken rewound the tape, the sound like a small motor racing.

I looked around the room. In a corner, someone had set up a puzzle board with cutouts in the shapes of ducks and chickens and horses. The wooden pieces that fit these cutouts had been scattered over the floor, and I imagined a child struggling to find the right place for the wooden rooster while a specialist stood over him, taking notes.

56 THE RUSSIAN WORD FOR SNOW

The tape stopped winding, and Ken pressed the remote. Grisha appeared, swimming across the screen.

I watched Jill's face, but she kept its broad planes blank, like the featureless masks that are sold at Halloween, masks that are often more frightening than those made to look like goblins or monsters.

"There's no vocalizing here," she said. For a moment I thought she was speaking to me.

"And no evidence of crawling ability," Sharon replied.

"I don't remember him tracking that squeeze toy."

"The giraffe."

"Did you notice the arms and legs?"

"Very rigid." Sharon made a fist with her fat little hand.

"But it's that expression that concerns me." Jill put a long finger on Grisha's sideways smile. "It doesn't seem to be caused by any outside stimuli."

Sharon hitched her chair closer. The backs of the two women were blocking the television. Grisha poked his face out from between their heads, as if looking for me.

"Heartbreaking," Jill repeated when the tape went to blue.

"What are you seeing?" I asked her.

"What we're looking for are developmental milestones," Sharon explained, "as well as evidence of basic neurological functions."

"Are you seeing something wrong?"

The room filled with the loud frightening sound of static.

"Sorry," Ken said, pressing buttons until the television turned off.

"Let me show you something." Sharon stood and I could see she was not much taller than a child herself. "I think you'll find this helpful."

She walked to a bookcase filled with videotapes and brought one back.

"May I?" she said to Ken, who had not let go of the remote.

On the screen, a middle-aged man in a suit sat beside a little girl with an elastic bow stretched around her bald head. The little girl looked to be about the same age as Grisha.

"This man is an expert in assessing childhood development." Sharon gave his image a little pat with her finger.

The man in the suit placed a tower of plastic blocks in front of the little girl, and watched with delight as she took them apart. He put a plastic dump truck in her lap, and clapped when the little girl pushed it over to him. He hid a stuffed monkey under his jacket and waited for the girl to find it. "Good job," he repeated each time the child completed a task. "Good job."

I wondered if Sharon meant to show us that Grisha was not like the little girl with the bow on her head? Wanted us to see that he would not be able to take apart the blocks, or push the truck? That the stuffed monkey would remain lost to him?

"Perhaps that's enough," Jill said, when the man began singing "The Itsy-Bitsy Spider."

Sharon turned off the television.

"Do you have any other information on this child?" Jill asked.