Seven

INTO THE COURTS

1.

In 1849, inspired by Henry Bibb’s memoir, the mathematician and militant abolitionist Elizur Wright predicted that “this fugitive slave literature is destined to be a powerful lever . . . an infallible means of abolitionizing the free states.” The reason, he wrote, is that unlike speeches and even sermons, the “narratives of slaves go right to the hearts of men.” If only one could “put a dozen copies of this book into every school district or neighborhood in the Free States,” stories like Bibb’s would “sweep the whole north on a thorough going Liberty Platform for abolishing slavery, everywhere and every how.”

Whatever their differences in tone or style, all the slave narratives of the 1830s and 1840s had a common purpose: to arouse sympathy for runaways and revulsion at the horrors from which they fled. They were written in impassioned language intended to make them painful and thrilling to read.

But in those same years, the dispute over slavery was proceeding on a parallel track in an entirely different kind of language—the dispassionate language of the law. “In the warm halls of the heart,” Herman Melville was soon to write, “memory’s spark” can “enkindle such a blaze of evidence, that all the corners of conviction are as suddenly lighted up as a midnight city by a burning building.” But “in the cold courts of justice” there are only “oaths” and “proofs.”

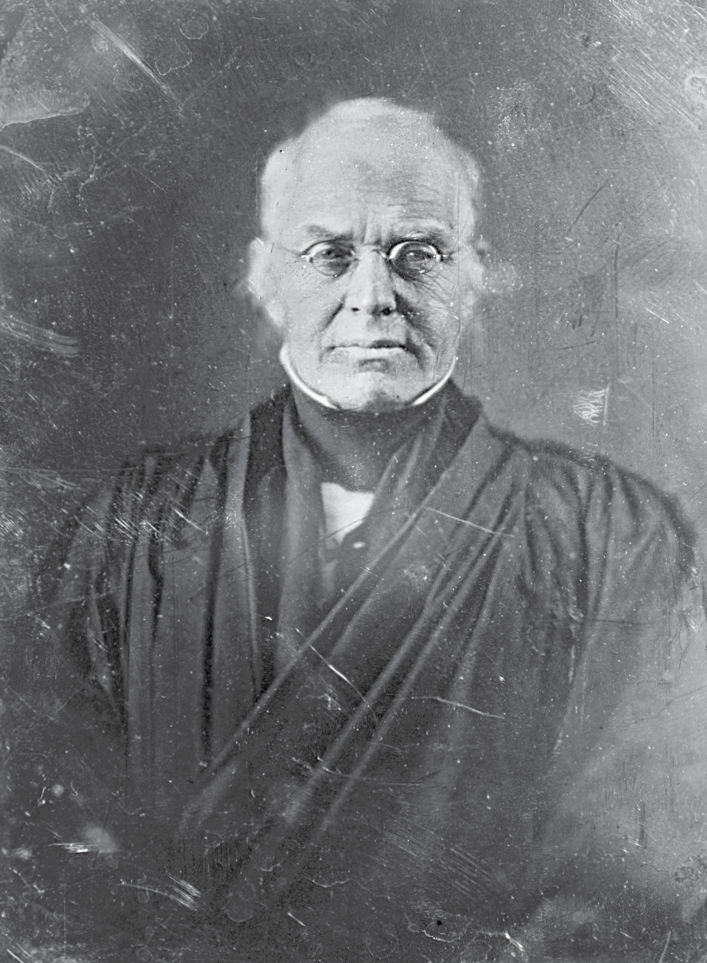

Every judge in every court had sworn an oath to uphold the Constitution. This was not an oath that could be selectively applied. “You know full well,” as Supreme Court justice Joseph Story wrote to a friend in 1842, “that I have ever been opposed to slavery. But I take my standard of duty as a Judge from the Constitution.” However repugnant he might find slavery and the props that supported it, he had sworn fidelity to Article 4, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution as much as to any of its other provisions. The “object” of that clause, as Story put it, “was to secure to the citizens of the slave-holding states the complete right and title of ownership in their slaves, in every state of the Union, into which they might escape.”*

As for the proofs, the Constitution was mute. And so it was up to Congress to determine which proofs would count. Congress had tried to meet this challenge by stipulating in the fugitive slave law of 1793 that an affidavit or oral testimony “taken before and certified by a magistrate” of the state to which a runaway had escaped was proof enough to send him back. Presented with such evidence, any judge charged with deciding the fate of any accused fugitive was expected, as today’s idiom would have it, to check his personal beliefs at the courthouse door.

Most did their best to do so. In an 1834 trial of a slave whose Louisiana mistress had tracked him to New York, Judge Samuel Nelson of the New York Supreme Court turned his courtroom into a classroom for instructing the public about what the Constitution said about runaways, and why:

At the adoption of the constitution, a small minority of the states had abolished slavery within their limits. . . . It was natural for [the southern] portion of the Union to fear that the latter states might, under the influence of this unhappy and exciting subject, be tempted to adopt a course of legislation that would embarrass the owners pursuing their fugitive slaves, if not discharge them from service, and invite escape by affording a place of refuge.

After concluding this history lesson, Nelson denied a writ of homine replegiando (personal replevin), which would have granted the defendant trial by jury, and ordered him into the custody of the Louisiana woman so she could take him back. “The right of the owner,” Judge Nelson said, “to reclaim the fugitive in the state to which he fled has been yielded up to him by the states,” and “it cannot be doubted, that under the provision of the constitution and laws, the right to this species of service is protected without regard to the residence of the owner.”

In a fugitive slave case ten years later, Judge Nathaniel Read of the Ohio Supreme Court distinguished, to the same effect, between the higher law of nature and the positive law of the land:

It being my duty to declare the law, not to make it, the question is not, what conforms to the great principles of natural right and universal freedom—but what do the positive law and institutions which we, as members of the government under which we live, are bound to recognize and obey, command and direct.

The Constitution, as Frederick Douglass put the matter, was a “living, breathing fact, exerting a mighty power over the nation of which it is the bond of Union.” For anyone who wondered just how mighty, Article 6, the so-called supremacy clause, spelled out the answer:

This Constitution, and the laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof . . . shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby, anything in the Constitution or laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding.*

These words would seem to have settled the matter once and for all: failure to return a fugitive upon presentation of due evidence of ownership was a violation of the slave owner’s constitutional rights. By swearing loyalty to the Constitution, every judge in every court had sworn to send the runaways back.

2.

To the extent that they were committed to working within the law, antislavery activists were therefore left with two options: obey the Constitution or alter it. But Article 5 set out a daunting process for making even the slightest change: an amendment must be proposed by a two-thirds majority of both houses of Congress (or by a convention called by two-thirds of the state legislatures) and then ratified by three-quarters of the states. Given the intransigence of the slave states on the fugitive slave question, this was plainly impossible. Writing in 1832, William Lloyd Garrison offered his view of a Constitution that not only protected slavery but, by blocking its own revision, protected itself:

A sacred compact, forsooth! . . . It was a compact formed at the sacrifice of the bodies and souls of millions of our race, for the sake of achieving a political object—an unblushing and monstrous coalition to do evil that good might come. Such a compact was, in the nature of things and according to the law of God, null and void from the beginning.

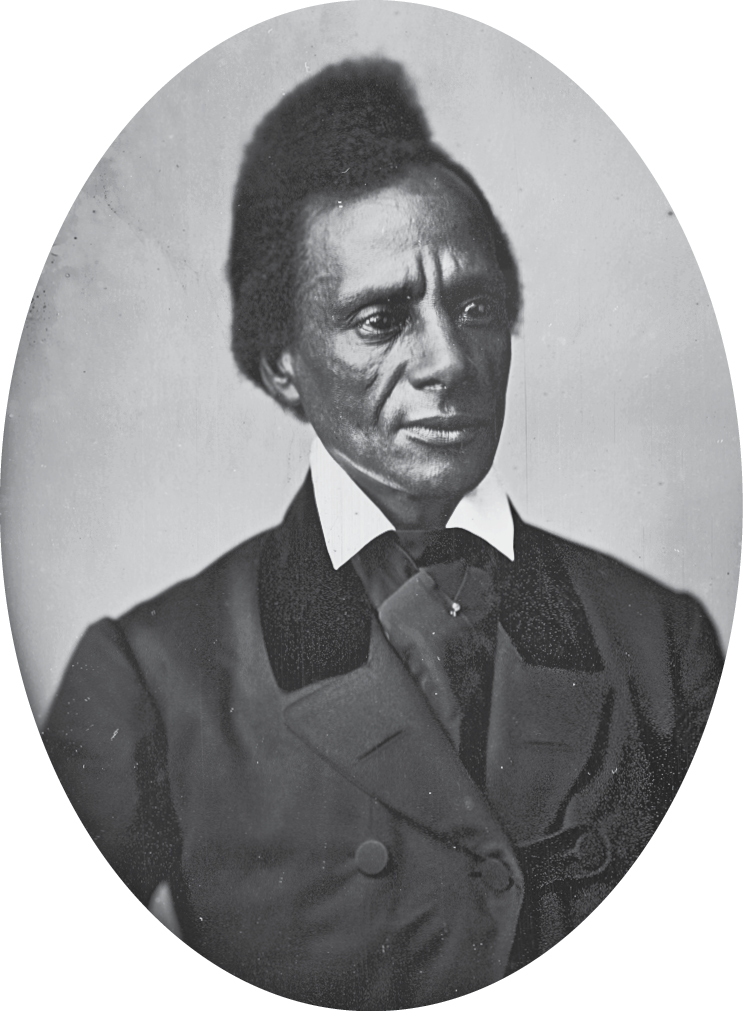

Some years later, the black activist Charles Lenox Remond amplified Garrison’s point. “It does very well,” he wrote in the National Anti-slavery Standard in 1844, “for nine-tenths of the people of the United States, to speak of the awe and reverence they feel as they contemplate the Constitution, but there are those who look upon it with a very different feeling, for they are in a very different position.” White Americans might regard it as a sacred document, but from the point of view of black Americans “slavery was in the understanding that framed” the Constitution, and “slavery is in the will that administers it.”

On this view, abolitionists of the Garrisonian stripe saw no choice for the free states but to secede and form a purified union of their own under a new constitution that would ban slavery altogether. Others, clinging to the hope that time would solve the problem, tried to convince themselves that the fugitive slave clause of the existing Constitution was a provisional necessity, a patch on a wound that would heal as the slave states slowly gave way under “moral suasion” to the higher law. Until such time as the patch could be removed without rupturing the wound, the right to recapture runaway slaves would remain in force.

Charles Lenox Remond

These ideas, far removed from the actual experience of enslaved men and women, had a certain cerebral abstraction, as if they were debating points. But when it came to flesh-and-blood fugitives whose fate depended on a proceeding in court, neither radicals who disavowed the Constitution nor conservatives who waited for a sea change in the national culture were of much use. There were, however, others in the antislavery movement—some of them gifted lawyers—who were neither ready to see the nation dissolved nor inclined to wait for the slave states to repent. Their strategy was to probe the internal contradictions of the Constitution in the hope of opening up some legal space through which at least a few fugitives might slip.

They pinned their hopes on the fact that while the Constitution required return of fugitive slaves, it also included—thanks, ironically, to slave owners such as Jefferson and Madison—a bill of rights designed to protect individual liberties against government intrusion. The pertinent words were those of the Fifth Amendment, which stated that “no person . . . shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” Like everything else in the Constitution, these words were of course open to interpretation, and so antislavery lawyers set to work.

The courts were their battleground, and the issue at stake was whether slave owners could pursue runaways without constraint. The words of the fugitive slave clause—“shall be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be due”—sounded clear enough, but how could the rendition requirement be reconciled with the requirement for “due process”? Did the founders really mean to grant unchecked power for seizing a person on the bald claim that someone owned him?

The law of 1793 had attempted to answer these questions, but in fact it only raised more questions. Soon after it was passed by Congress, one Massachusetts representative protested on the floor of the House that it was an invitation for kidnappers to seize anyone they fancied on the pretext that they were acting on behalf of a slave owner exercising his property rights. “The person may be a freeman,” he pointed out, “for it would not be easy to know whether the evidence was good, at a distance from the State; the poor man is then sent to his State in slavery.” By the turn of the century, northern legislatures were responding to what they regarded as a dangerous federal law by passing state laws intended to provide protection against it.

These laws came to be known as “personal liberty” laws. In the first four decades of the nineteenth century, such laws were adopted throughout the free states, from Ohio to Vermont, with the cumulative effect of making it more difficult to extradite an accused runaway to a slave state. The most stringent was Pennsylvania’s 1826 “Act to Give Effect to the Provisions of the Constitution of the United States, Relative to Fugitives from Labor, for the Protection of Free People of Color, and to Prevent Kidnapping,” provoked in part by a notorious abduction of several black boys from the Philadelphia docks, where they were lured aboard ship and taken to Georgia and Mississippi as slaves. Pennsylvania was a common destination for fugitives from Maryland, Virginia, and points south, and among all the free states bordering on slave states (Iowa, Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey), it went furthest in protecting free blacks born or living for years in the state, as well as in making it difficult to retrieve recent runaways. By excluding testimony from the slave owner himself, the Pennsylvania law forced him to prove his “claim to a runaway by informed and impartial witnesses”—presumably men from his home state for whose time and travel expenses he would have to pay.

In the minds of supporters, personal liberty laws such as the Pennsylvania law of 1826 embodied a cardinal principle of American jurisprudence: even at risk of acquitting guilty persons (in this case, guilt meant fleeing for freedom), innocent persons, namely free blacks in the North claimed as runaways by whites in the South, must be afforded such basic rights as trial by jury and immunity against self-incrimination. For opponents, the personal liberty laws had nothing to do with protecting free citizens. The real aim of these laws was to obstruct slave owners by dragging them into a bureaucratic nightmare if they tried to reclaim property to which they had legitimate title. And so the personal liberty laws became another flash point between North and South.

Still, when it came to the constitutional principle that a slave could not achieve freedom by moving from South to North, the personal liberty laws only nibbled at the edges. Then, in 1836, the Massachusetts Supreme Court took a bite.

3.

Mary Slater, a resident of New Orleans, had come to Boston to visit her father, Thomas Aves. She brought with her a slave named Med, a girl of about six years old who belonged, according to the laws of Louisiana, to her husband. When Mrs. Slater became ill, she left the child with her father under his protection—or, from the point of view of antislavery Bostonians—in detention. When news reached members of the Boston Female Anti-slavery Society that a slave girl was being held in the heart of their city, they sought a writ of habeas corpus challenging Aves’s right to keep her. He responded that he was acting as agent for his son-in-law, the girl’s legal owner, until such time as the child could return to Louisiana in the company of Mrs. Slater or some other responsible party. In August 1836, the case reached the Massachusetts Supreme Court, presided over by Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw.*

The substantive issue facing the court was whether an enslaved person from another state could be forcibly returned from Massachusetts into slavery. This was not quite the same question Judge Nelson had faced in the New York case of 1834, because the defendant in that case had been charged as a fugitive. In the Aves case, the little girl had been brought into the state by an agent of her master (his wife), and no one accused her of having run away. Massachusetts also had a distinctive history with slavery. New York had been late in abolishing it (its last slaves were not emancipated until 1827), and slave owners who brought human property into the state were still granted a nine-month grace period before any such slave could claim freedom. In Massachusetts, where slavery had been illegal since 1783, there was no law prescribing one way or another the status of a slave brought in from another state.

Now, thanks to the interest of the Boston Female Anti-slavery Society in a six-year-old girl, that issue would have to be faced. Was the fact of her presence in Massachusetts reason enough to free her? Or, as Judge Nelson had ruled, was it true that to a “qualified extent slavery may be said still to exist in a state, however effectually it may have been denounced by her constitution and laws”—to a sufficient extent, that is, that a slave remained enslaved while traveling to a free state in the company of her master?

Benjamin R. Curtis, the attorney for Aves, answered this question in the affirmative. He argued on the principle of “voluntary comity” that Massachusetts owed deference to the laws of Louisiana, regardless of what feelings those laws might affront. The attorney for the plaintiffs, Ellis Gray Loring, countered that the principle of comity did not apply. There had been no slaves in Massachusetts for over fifty years, so the very idea of comity was a farce. Besides, Louisiana was known for throwing into jail black sailors who arrived in one of its ports aboard Massachusetts-registered ships. According to the principle of comity, should Massachusetts reciprocate by jailing citizens of Louisiana upon their arrival in Boston Harbor?

To the consternation of some northern conservatives, and to the horror of many in the South, Judge Lemuel Shaw came down on Loring’s side of the argument. Comity, he ruled, applied “only to those commodities which are everywhere and by all nations, treated and deemed subjects of property.” People were not recognized as property in Massachusetts. Med was removed from the custody of Mr. Aves and released.

She was given over for protection to members of the Boston Female Anti-slavery Society, who assigned her a new name, Maria Somerset, in dual honor of their founder Maria Weston Chapman and the liberated slave in the famous Somerset case. Perhaps Shaw expected that someone in the society would adopt her. Instead, she was sent to an orphanage. Whether this was because of the limits of Boston charity or because the child’s bewilderment at being kept from her family in Louisiana made her frantic and unmanageable is not known.

The Aves case set an important precedent. Over the next few years, many northern states followed it by granting freedom to slaves belonging to masters who voluntarily brought them into the state. Even historically slow New York repealed its statute granting slave owners a nine-month reprieve before their slaves were declared free. Nevertheless, one can feel Shaw straining, almost squirming, as he took pains to deny that a slave, simply by being carried to a free state, is released in any metaphysical sense from his status as a slave:

Although such persons have been slaves, they become free, not so much because any alteration is made in their status, or condition, as because there is no law which will warrant, but there are laws, if they choose to avail themselves of them, which prohibit, their forcible detention or forcible removal.

But the basic problem of the legal status of fugitive slaves remained, and Shaw knew it. According to the Constitution, which was the supreme law of the land, fugitives who had run from their masters were exempt from any prohibition placed by state law against “detention or forcible removal.” In Shaw’s mind, therefore, the whole case turned on the meaning of “escaping.” “The claimant of a slave, to avail himself of the provisions of the constitution and laws of the United States,” he said, “must bring himself within their plain and obvious meaning,” which “in the constitution is confined to the case of a slave escaping from one state and fleeing to another.”

By this logic, if Med had run into the arms of the Female Anti-slavery Society begging for sanctuary, Shaw might well have regarded her as a fugitive and returned her to slavery. But because she was not guilty of escaping, and remained entirely passive—carried into the state like a package, and docile once she got there—he set her free.

4.

Suddenly Lemuel Shaw was a hero to the antislavery movement. Garrison, not exactly known for respecting jurists, called him “rational, just,” and even “noble.” Yet as a legal precedent, the Aves case proved to be a diversion from the more contentious problem of how the law should deal with slaves who had run from their masters.

In most such cases, the masters prevailed. Few judges concurred (though they might have wished to) with Judge Theophilus Harrington of Vermont, who was reputed to have said back in 1807 when presented with documents purporting to prove the identity of a fugitive, “If the master could show a bill of sale, or grant, from the Almighty, then his title to him would be complete: otherwise it would not.” Throughout the 1830s and 1840s, convictions were the norm, though judges often handed them down in language tinged with resignation and regret.

Even lawyers for the plaintiffs sometimes gave voice to the “alas my hands are tied by the Constitution” theme. In Pittsburgh, not long before the Aves case, a fugitive named Charles Brown was apprehended by agents for his Maryland owner, who had advertised for his return, making little distinction between the goods (“blue cloth coat,” “white fur hat”) with which Brown had absconded and Brown himself:

Stop the thief—50 dollars reward.—Ran away from the subscriber’s farm, near Williamsport, on Saturday night last, a negro boy, who calls himself Charles Brown, 18 years old, about 5 feet 9 or 10 inches high, not stout, but well proportioned; of a dark complexion, and good countenance. Had on and took with him, one fine blue cloth coat, half worn, white fur hat . . . one pair new drab corduroy pantaloons, one black silk vest, one fine muslin shirt, . . . one light drab home-made cloth short coat, one or two pair of double threaded cotton pantaloons, one pair white cotton drilling . . . fine shoes, stockings, and other articles not remembered. He rode away a sorrel mare, about 15 years old, with white blaze in the face, both hind feet believed to be white; paces and trots, and when pacing, throws one of her feet a little out, as if stiff in the joint.

Arguing that Brown must be restored to his master, the slave owner’s attorney tried to soften his argument with expressions of lament (“God knows no man . . . more regrets the black spot of slavery on our national escutcheon than I do”) before turning to the judge to say that he, too, must defer to mind over heart:

And you, sir, certainly, acting under oath, will not yield to your abhorrence of the curse of slavery, in deciding a question which comes directly to your conscience, acting under oath; nor strain a point to deprive one of your fellow-citizens, of Maryland, wrongfully of his lawful property.

Two years later, in an 1837 case that gained national attention, a young enslaved woman named Matilda had been brought from Missouri to Ohio by her owner—who was also her father—a man named Larkin Lawrence. After he refused to grant her freedom, she fled and was hired as a household servant by James Birney, the Kentucky-born slave owner turned abolitionist, who was living in Cincinnati. It is not clear whether Birney, who had once owned a cotton plantation in Alabama but was now publishing an antislavery newspaper, the Philanthropist, knew she was a fugitive. In any case, when Lawrence’s agents found her in his charge, Birney surrendered her, and she was brought to court.

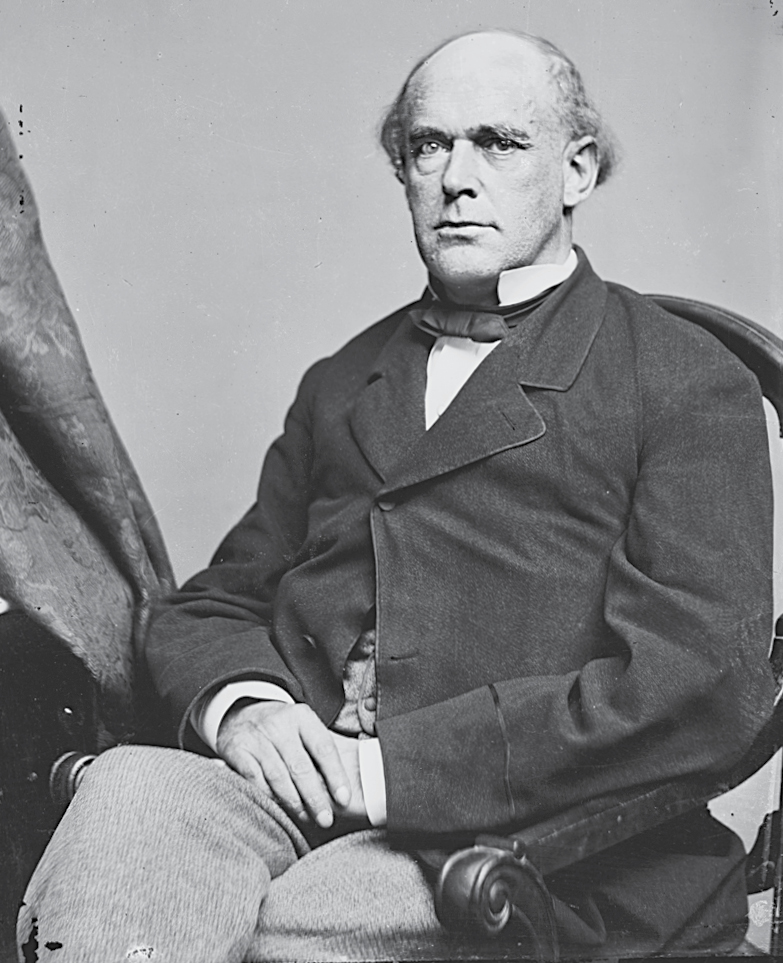

Matilda was represented by Salmon P. Chase—the future Ohio senator and governor, later secretary of the Treasury and chief justice of the United States. Raising his sights heavenward, Chase noted that slavery would never survive a weighing in “the golden scales of justice . . . on high.” Then, lowering his gaze, he conceded that “the right to hold a man is a naked legal right”—a right, that is, defined not by God in heaven but by legislatures and courts on earth. Still, as Judge Shaw had ruled in the Aves case, this right was not unlimited. “It is a right which, in its own nature, can have no existence beyond the territorial limits of the state which sanctions it, except in other states where positive law recognizes and protects it. It vanishes when the master and the slave meet in a state where positive law interdicts slavery.” But because Matilda had run from her owner, Chase still had to find a way to save her from the constitutional demand that runaways be returned. On the principle that “the moment the slave comes within such a state, he acquires the legal right to freedom,” he tried to convince the court that Matilda was not a fugitive at all because she had been brought to Ohio by her master and only upon reaching free soil had she attempted to escape.

Justice John McLean of the U.S. Supreme Court (serving on the western circuit at the time) was unconvinced. He admonished the jury to suppress its feelings and observed that

in the course of this discussion, much has been said of the laws of nature, of conscience, and the rights of conscience. This monitor, under great excitement, may mislead, and always does mislead, when it urges anyone to violate the law. I have read to you the Constitution and the acts of congress. They form the only guides in the administration of justice in this case.

The law was the law. Divine justice was something else. Matilda was removed to the custody of her owner. What became of her is unknown.

Salmon P. Chase

And so it went in case after case. Under the suffocating precedent of the Constitution, antislavery lawyers fought for breathing room, but they seldom found it. Five years later, in the spring of 1842, also in Ohio, a pious antislavery man named John Van Zandt, who had once been a slave owner in Kentucky (he became the model for the virtuous John Van Trompe in Uncle Tom’s Cabin), encountered a group of nine slaves on the run from his home state. He hid them in his wagon, where they were discovered by slave catchers hired by their owner. Eight were returned to Kentucky; one escaped.

Obliged under Kentucky law to pay the slave catchers a monetary reward for their services, and deprived of the slave who had successfully fled, the slave owner sued Van Zandt for damages totaling twelve hundred dollars. The case was eventually heard in 1847 by the U.S. Supreme Court, where Salmon P. Chase—assisted by William H. Seward—was once again counsel for the defense.

This time he tried some novel arguments. The law of 1793 penalized anyone who “shall harbor or conceal” any “person after notice that he or she was a fugitive from labor,” but Chase claimed that Van Zandt had been unaware that the people whom he had treated with Christian charity were fugitives, and therefore he should not be convicted of having harbored them. Chase then launched into a lengthy disquisition on the etymology and definition of the word “harbor,” citing Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary and Shakespeare’s King John, to which Seward later added the name of the French port city of Le Havre in order to make the case that “the idea of motion, progress, flight, or escape is absolutely excluded” from the meaning of the word. Therefore Van Zandt could not possibly be guilty of harboring anyone. In another act of intellectual contortion, Chase even claimed that the law of 1793 and the constitutional clause itself applied only to the original thirteen states in existence at the time they were written, and because Ohio did not enter the Union until 1803, Ohioans were exempt. These were all extravagant arguments. Writing for the Court, Justice Levi Woodbury of New Hampshire rejected them, and Van Zandt’s conviction was upheld.

5.

Because of the stranglehold of the Constitution, everyone in the antislavery movement understood that runaways and their accomplices faced long odds in court no matter how ingenious their lawyers might be. And so the more militant among them tried to save them from coming to court at all. “Vigilance committees” formed throughout the North—groups of citizens, black and white, in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Albany, all the way to Pittsburgh and Detroit, committed to aiding and sheltering fugitives, to spreading the word when slave catchers showed up, sometimes even to breaking captives out of detention and getting them out of town. Still, the legal machine ground on. Then in 1842 came the first decision concerning the fugitive slave problem ever to be rendered by the U.S. Supreme Court—with larger implications than any previous ruling in any fugitive slave case.

A collision between the federal fugitive slave law of 1793 and the Pennsylvania personal liberty law of 1826 had long been brewing. One purpose of the federal law had been to spare slave owners from delays and burdensome expenses. But the Pennsylvania law, by requiring a warrant from a Pennsylvania judge before an accused person could be arrested, made delay not only likely but long enough for vigilant citizens to hide him or help him to flee farther north. The Pennsylvania law also provided, regardless of the outcome of the case, that slave owners could be charged with court expenses. And while federal law allowed for penalties to be imposed on persons hindering the return of fugitives, the Pennsylvania law granted slave owners only the right to pursue damages, which would entail yet more court proceedings, more time, and more expense. In short, it was designed to make things as difficult as possible for slave owners to retrieve their runaways.

It was under these circumstances that a woman enslaved in Maryland named Margaret Morgan fled, in 1832, to Pennsylvania, where she joined her free black husband and, over the ensuing years, gave birth to several children. In 1837, a Maryland white woman who, under Maryland law, had inherited Margaret as well as her children hired an attorney named Edward Prigg “to seize and arrest the said negro woman” as her rightful property. Prigg attempted to obtain a warrant from a Pennsylvania justice of the peace, who refused. He then decided to sidestep the legal process and brought Margaret Morgan and her children back to Maryland by force. Prigg was charged in a Pennsylvania court and convicted of kidnapping, a judgment affirmed by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court—at which point he appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States. It was the first time a fugitive slave case reached the nation’s highest court.

Writing for the high court on March 1, 1842, Justice Joseph Story found the 1826 Pennsylvania personal liberty law unconstitutional. Like other judges before him, he supplemented his verdict with a history lesson, pointing out that if the founders had not agreed on a constitution requiring the return of fugitive slaves—odious as that might be to lovers of freedom—every free state could “have declared free all runaway slaves coming within its limits” and would thereby have created “animosities” so “bitter” that “the Union could not have been formed.” Story went on to declare that “any state law or state regulation, which interrupts, limits, delays, or postpones the right of the owner to the immediate possession of the slave, and the immediate command of his service and labour” was invalid.

Joseph Story c. 1844

It was a bombshell. The Court had effectively struck down all legislative efforts by northern states to impede the fugitive slave clause of the Constitution. All protections for accused runaways had been swept away, including provisions for due process set out in the personal liberty laws. “One-half of the nation,” as one historian puts it, “must sacrifice its presumption of freedom to the other half’s presumption of slavery.”

And yet Story gave something to the antislavery side too. Even as he upheld the constitutionality of the 1793 federal fugitive slave law by striking down state laws designed to interfere with it, he gave implicit permission to states to invent new ways to weaken or even render it useless. His decision left room for states to deny the use of state officials and facilities—justices of the peace, police officers, jails—for enforcing the federal law, and thereby to leave the work entirely up to federal authority. “The provisions of the act of 12th February, 1793, relative to fugitive slaves,” Story wrote, “is clearly constitutional in all its leading provisions, and, indeed, with the exception of that part which confers authority on state magistrates, is free from reasonable doubt or difficulty.” Then he noted a momentous exception:

As to the authority so conferred on state magistrates, while a difference of opinion exists, and may exist on this point in different States, whether state magistrates are bound to act under it, none is entertained by the Court that state magistrates may, if they choose, exercise the authority unless prohibited by state legislation.

In short, while no state law may impede the claimant in a fugitive slave case, and state officials may aid the process of arrest and rendition “if they choose,” they are not obliged to do so.

With five words—“unless prohibited by state legislation”—Story had unleashed, perhaps unwittingly, what would become a second wave of personal liberty laws. Over the next few years, states throughout the North passed new laws forbidding state officials to cooperate in the rendition of fugitives. The federal government at the time had few resources to make its laws stick, and so what the states were saying to the government in Washington was essentially, “Do your own dirty work. We won’t help.”* In a memoir of his father published in 1851, Justice Story’s son looked back at the Prigg decision with filial pride and called it a “triumph of freedom.”

Even before the rise of the new personal liberty laws, the Prigg decision was put to the test. The first test came in October 1842, once again in a Massachusetts courtroom presided over by Judge Shaw. A Boston police constable, armed with a warrant obtained from the Boston Police Court by a Virginia slave owner, arrested a young black man named George Latimer and held him in the Leverett Street jail. Word quickly spread, and concerned Bostonians petitioned Judge Shaw for a writ of habeas corpus. The writ was granted and the prisoner was brought before the state supreme court for a hearing to determine if he could be released on bail pending a hearing on his case in federal court.

This time, in the eyes of abolitionists, Shaw did not emerge a hero. He was firm in regarding the case as a federal matter and ruled that under the act of 1793, recently upheld in Prigg v. Pennsylvania, the slave owner and his agents had due authority to have the prisoner held as a suspected runaway until a federal court ruled on his fate. While transferring Latimer back to the city jail, officers of the court were attacked by a mob, with at least one person seriously hurt. Latimer remained in detention pending a rendition hearing before the federal judge—who happened to be Justice Story, on circuit duty—to whom Latimer’s putative owner would presumably present proof of ownership.

In the interim, abolitionists tried various strategies to get the prisoner released. Among them was a writ of personal replevin—the same legal instrument presented to Judge Nelson in the 1834 New York case, which, if accepted, would have required trial by jury. When they took the matter again to Judge Shaw, his response was summarized by William Lloyd Garrison, who was present in the courtroom:

He probably felt as much sympathy for the person in custody as others; but this was a case in which an appeal to natural rights and the paramount law of liberty was not pertinent! It was decided by the Constitution of the United States, and by the law of Congress, under that instrument, relating to fugitive slaves. These were to be obeyed, however disagreeable to our own natural sympathies. . . . He repeatedly said, that on no other terms could a union have been formed between the North and the South.

Soon thereafter, Garrison, who had once praised Shaw for his wisdom and probity, excoriated him for playing “the part of Pilate in the Crucifixion of the Son of God.”

The Latimer case drove Boston into a fury. “Fire and bloodshed,” according to one observer, “threatened in every direction.” Petitions with over sixty-five thousand signatures and weighing more than 150 pounds were delivered in a barrel to the Massachusetts State Senate demanding a new law prohibiting cooperation by state authorities in any fugitive slave case. Another barrel of petitions beseeching Congress “to pass such laws and to propose such amendments to the Constitution of the United States as shall forever separate the people of Massachusetts from all connection with slavery” was sent to seventy-five-year-old John Quincy Adams, who attempted to present them in the House but was rebuffed on authority of the gag rule. Asked to serve as counsel for Latimer, Adams declined on the grounds that his legal skills were out of practice,* but he agreed to advise Latimer’s attorneys “subject to my bounden duty of fidelity to the Constitution of the United States.”

Abolitionists published a broadside called the Latimer Journal and North Star, in which they reported the latest events three times a week. “The slave shall never leave Boston,” they said, “even if to gain that end the streets pour with blood.” Meanwhile, the hearing in federal court had been delayed, possibly because Justice Story was ill or because he wished to grant the slave owner sufficient time to obtain proof of ownership from his home state.

During the wait, pressure mounted on city authorities to release the prisoner to the custody of the claimant because holding Latimer much longer seemed likely to precipitate a riot. On November 18, the sheriff of Boston ordered that he be turned over to the Virginian—a nervous stranger in a hostile city—who now feared less for his property than for himself. When a group of abolitionists raised four hundred dollars to buy Latimer’s freedom, he accepted the offer and the case was closed.

But not quite. On March 24, 1843, Massachusetts legislators walked through the door that Justice Story had opened. The legislature passed what became known as the “Latimer law,” prohibiting state officials from detaining anyone charged under the 1793 fugitive slave law and from using any state facility for that purpose. Over the next few years, similar statutes were adopted in Pennsylvania, Connecticut, New York, and Rhode Island. Bostonians were proud to have taken the lead. John Greenleaf Whittier (echoing the English poet William Cowper’s celebration of the Somerset verdict some sixty years earlier) exulted:

No slave-hunt in our borders,—no pirate on our strand!

No fetters in the Bay State,—no slave upon our land!

6.

But the legal battles were by no means over. Four years after the Latimer case, and three months after the Van Zandt conviction was upheld by the Supreme Court, another fugitive slave case made national news by proving the potency of the new personal liberty laws.

In June 1847, a pair of Maryland slave owners traveled to the town of Shippensburg, in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, searching for three fugitive slaves rumored to have fled there—a man and a girl of about ten (possibly father and daughter), as well as an adult woman married to a free black man living nearby. The Maryland men forced their way into the house where the runaways were harbored, brought them to the county seat, Carlisle, and presented their claim of ownership to the local justice of the peace, who jailed the fugitives and, under the fugitive slave law of 1793, granted a certificate authorizing their return to Maryland.

But before the slave catchers could complete their mission, they ran into legal complications. The Cumberland County judge was presumably aware of the Prigg decision, including its stipulation that state authorities may assist in the rendition of fugitives “unless prohibited by state legislation,” but when a local lawyer presented him with a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of the prisoners, it became clear that the judge was unaware of the new personal liberty law passed two months earlier by the Pennsylvania legislature forbidding the use of “any jail or prison for the detention of anyone claimed as a fugitive.” When a theology professor from nearby Dickinson College showed him a copy of the statute, which was modeled on the Massachusetts “Latimer law” of 1843, the judge allowed rendition of the runaways to proceed but voided the authority of the local sheriff to hold them in custody pending their return to Maryland. In short, the slave catchers would be allowed to complete their business, but as for holding and transporting their captives, they were on their own.

This was just the sort of hairsplitting that southerners had feared ever since the Prigg decision. One Maryland newspaper lamented that the new Pennsylvania law was intended “to destroy the force of the law of congress of 1793.” To all intents and purposes, it did.

As the dispute inside the Carlisle courthouse heated up, so did the racially mixed crowd gathered outside. Whites mostly clamored for the slaves to be sent back to slave country, while blacks (roughly three hundred free black citizens lived in Carlisle and environs, of whom scores had shown up at the courthouse) demanded their release. When the captives were finally brought out onto the courthouse steps, dozens of black men, “seeing their fellows about to be carried away into interminable bondage,” suddenly “made a rush, and carried off the woman and child.” During the melee, one of the Maryland men was trampled and severely injured. A few days later he died. Thirty-four local black residents, including nine women, were arrested on charges ranging from assault to murder, and the Dickinson College professor was charged with inciting the riot.

Two months later, a jury convicted thirteen black defendants and acquitted the white professor. The Cumberland County judge, who had wanted to see the whole lot locked up, denounced what he regarded as the weakness of the verdict and sentenced eleven of the convicted men to three years’ solitary confinement in the Eastern State Penitentiary. The following spring, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court reviewed the case, released all the defendants, and, in a rebuke of the judge, noted that three-quarters of a year spent in the penitentiary was more than enough punishment for their putative crimes.

News of these events spread far and wide. Moncure Conway, a Dickinson student from Virginia who was soon to join other conscientious objectors to slavery in the South such as James Birney and Angelina Grimké by exiling himself to the North, recalled years later that there was “probably not an abolitionist among the students, and most of us perhaps were from the slave States.” Yet most came to the defense of their professor in a series of resolutions that were published in national antislavery newspapers.

Some local papers (reflecting not only racial animus but also, perhaps, a degree of “town-gown” hostility) took a different tack, declaring that the root problem behind the case was the fact that too many black people—slave and free—were entering Pennsylvania. Referring to the death of the Maryland man, one paper proclaimed that “the Abolition fanatics can now witness the first and choice fruits of their maddened zeal” and went on to

question whether it was a sound policy to permit blacks of all descriptions and characters such unrestricted liberty to come and settle among us. We appear to be the Botany Bay* for the African race. Every runaway negro finds a home in Pennsylvania. Is not this evil becoming a crying one? Should it not be remedied? . . . It is not to be denied that a large portion of the time of our Criminal Courts are taken up in trying worthless vagabond negroes, for almost every species of crime at a great expense to the public. They fill our poor houses and jails and this alarming evil is on the increase.

In short, lax immigration laws were to blame for rising crime rates. As we lately have been reminded, this facile explanation has perennial appeal.

The full implications of the Supreme Court decision in Prigg v. Pennsylvania were becoming evident. On the one hand, it reaffirmed the basic principle of the Constitution and the law of 1793—that slave masters had the right to retrieve their slaves from wherever within the United States they had fled. On the other hand, because state legislatures could forbid state authorities to assist them in exercising that right, it had become merely a nominal right—a paper privilege with little value in the real world.

Perhaps the largest consequence of the court battles leading to and flowing from the Prigg decision was that people on both right and left were losing faith in the legitimacy of legal and political institutions. John C. Calhoun deemed the personal liberty laws “one of the most fatal blows ever received by the South and the Union.” For William Lloyd Garrison, the spectacle of judges upholding the right of slave owners to retrieve their slaves, however much the personal liberty laws might retard the process, only confirmed that “villainy is still villainy though it be pronounced equity in the statute book.”

Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, an astute student not only of constitutional history but of political reality, summed up the impact of the Prigg decision: “This decision of the Supreme Court—so clear and full—was further valuable in making visible to the legislative authority”—namely, Congress—“what was wanting to give efficacy to the act of 1793; it was nothing but to substitute federal commissioners for the State officers forbidden to act under it.” Sooner or later, in other words, the federal government would have to step in by creating a class of “commissioners” to do what state officials were refusing to do. The path forward—or backward—was clear, but it would be three more years before Congress would embark on it.