CHEAP THRILLS

Bluebeard in Chapbooks and Juveniles

Bluebeard came to prominence through the eighteenth century initially in the form of reprints and pirated knockoffs of Mother Goose tales, quickly breaking out into chapbook form. The term chapbook refers to small, cheaply printed books, crudely illustrated, and even more crudely sewn, which were in circulation throughout the British Isles by the hundreds of thousands in their heyday (1750 to 1850). These books were distributed to every rural area of Britain on foot by chapmen (also known more prosaically as traveling-, running-, or flying-stationers; peddlers, packmen, or hawkers). By the late eighteenth century, “Bluebeard” was headlining many of these same chapbooks alone or with one or two other tales, divested of the rest of the Mother Goose set (which of course continued to be reprinted, as they have been to the present day). It was through these cheap, ephemeral chapbooks, rather than the more expensive and elaborate printings of Mother Goose, that the majority of households of the period across all classes came to know Bluebeard.1

A common feature of chapbooks, which will have relevance to the study of extant Bluebeard chapbooks and the difficulty of distinguishing them, is that they were commonly pirated. Rival printers freely and routinely stole each others’ texts, and copyright was largely ignored (Darton 1932, 70).2 The chapbook phenomenon in England and Scotland in particular (little is known about Welsh and Irish production of chapbooks) is contemporary with that in other European countries. Chapbooks were printed and distributed in France from the time the printing press was invented and were known there as livres de colportage, referring to the neck (col) bag that was used to carry (porter) the books; or the bibliothèque bleue in reference to the books’ cheap blue paper covers. While America imported these books by the tens of thousands for sale in peddlers’ packs, Harry Weiss in his several studies of American chapbooks commented that there was never the same type of explosion of chapbooks in America as in Europe (1942, 124). Nonetheless, they were imported in huge numbers.3 The phenomenon peaked early in the nineteenth century, and chap-books all but expired in the second half of that century. As early as 1882 in his major work on chapbooks, Chap-Books of the Eighteenth Century: With Facsimiles, Notes, and Introduction, John Ashton called them relics, in need of a rescue “from the limbo into which they were fast descending” (xii). As Ashton’s work demonstrated, while they were dying out of popular culture, chapbooks were becoming a subject for scholarly collection and study for the first time. In the past, they may have been collected for their sentimental value, as they were notably by James Boswell, who returned to a bookseller to purchase and bind together a sample of the reading materials of his youth4; they were also collected from boyhood by Sir Walter Scott, who said he had them “from the baskets of the travelling pedlars” (Corson 1962, 203). But the first scholarly commentary on chapbooks both owes its derivation to the increasing scarcity of the now-prized “waifs of past popular literature” (Bergengren 1904),5 and perhaps to the study of and credibility given to popular culture akin to the rise of folklore studies (by which means Bluebeard chapbooks could be interesting twice over).

In addition to being the means by which Britain came to know Bluebeard with great familiarity, these slight chapbooks are credited with preserving fairy tales altogether.6 Fairy tales had a solid niche in the chapbook market, but the concept of a book market for children was comparatively new. John Newbery is credited with realizing the market potential in England for children’s literature, beginning as late as the mid-1740s.7 In her study of Mother Goose, Ségolène Le Men pointed to the shift in audience from adults to children, positing that this shift actually occurred in England (1992, 35).

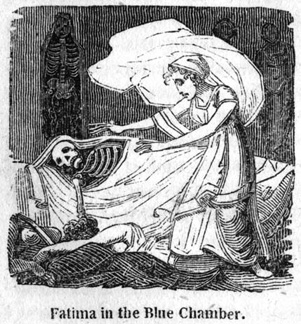

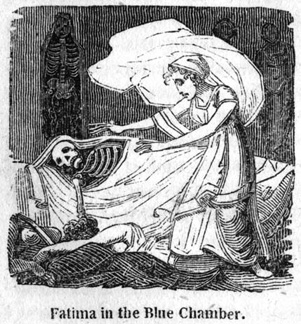

In chapbook form, it is fascinating to see what permutations the tale takes from the original and even from the first two major English translations (by Robert Samber and G. M.). Once firmly and thrillingly installed in the chapbook tradition and freed from the context of Mother Goose collections that more or less consistently followed the translations of either Samber or G. M., “Bluebeard” of course changed. The strain of orientalism, by which the nineteenth-century audience came to know Bluebeard as a Turk, his wife as Fatima, and which on the stage both comic and serious created a host of named “extras,” took permanent root in the chapbook tradition. Given that it was in chapbooks that Bluebeard reached his widest audience, it is interesting to see just what story they were telling.

Chapbook illustration, “Fatima in the Blue Chamber.” Printed for N. Hailes, Juvenile Library. 1817. Blue Beard: Adorned with Cuts. Courtesy of The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

Charles Perrault claimed the tales from the oral tradition for children and rewrote them for an adult salon readership. In chapbooks, though, they were primarily returned to children, for whom these chapbooks were bought and by whom they were read and exchanged. Compellingly, the very first example of what an actual reader of chapbooks remembers reading in his childhood in the early 1800s, quoted in a book-length study of the chapbook phenomenon in England, is: Bluebeard.8 The penchant for multiple illustrations in the chap-books no doubt helped to ensure a broad audience.

A representative chapbook is one published by Dean & Son,9 who had several versions of the Blue Beard story in chapbook form throughout this century: Blue Beard, or, Female Curiosity. The chapbook is 12 pages and illustrated. It is already distinguishable from the lower end of rough-and-ready chapbooks by the fact that the illustrations are, for the most part, both pertinent to the story they are illustrating and consistent with one another. The cover is illustrated with a woman seated with a child, reading, on her lap. The back cover lists “13 sorts” in this series of “Children’s Popular Tales,” all at “1d. each, Plain, or 2d. Coloured,” as follows: Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves; Whittington and His Cat; Blue Beard, or Female Curiosity!; Butterfly’s Ball and Grasshopper’s Feast; Jack, the Giant Killer; Cat’s Castle Besieged by the Rats; Little Red Riding Hood; Cinderella and Her Little Glass Slipper; Children in the Wood; Death and Burial of Poor Cock Robin; Jack and the Bean Stalk; Old Mother Hubbard and her Dog; Valentine and Orson. More than half of these titles are familiar staples among chapbooks. In the center of the Bodleian copy’s cover is the title: Blue Beard, or Female Curiosity. At the bottom is the name and address of the publisher, and the price: “Dean & Son, Threadneedle St, One Penny.”

Chapbook illustration. From Dean & Son. 1854–1856. Blue Beard, or, Female Curiosity. Courtesy of The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

Directly on opening the chapbook, the interrelationship between illustrations and text is strikingly apparent. The verso of the title page has the title: BLUE BEARD above two half-page illustrations, while its facing recto page has yet another illustration above the text. Visually, nearly three-quarters of the two pages are illustrations of the story, and all precede the text. Somewhat unusually, restraint has been shown in not yet illustrating any of the three most iconic moments of the tale: the chamber discovery, the near-execution, or the simultaneous signaling and arrival of the rescuing brothers, which, if not already on the cover page, frequently serve as introduction to the tale. This Dean & Son version does make up for the lack by having two renditions of the near-execution depicted within the text: one before the wife has been granted her time to pray, and the other in its usual spot, after this time has elapsed. But at the beginning, this Dean & Son chapbook shows first, a woman sitting on a balcony, Bluebeard standing to her left, scimitar hanging below his waist, his left arm behind his back, his right arm over her shoulder. His cloak is trimmed with ermine. Below, in the bottom half of the page, Bluebeard is in the right foreground, unsheathing his scimitar, and there is a ship in the background taking up the left half of the picture. This picture, scimitar aside, is the only one not entirely consonant with the rest of the illustrations, which all depict Bluebeard dressed alike; in this one, he is in trousers instead of kaftan. In the third picture, the couple is walking by an elaborate fountain. Bluebeard is steering the woman with his left arm; with his right he is gesturing to the fountain. The images symbolize, in turn: courtship, power, and wealth. The overall effect in these first three illustrations, seen almost simultaneously, is the overwhelming presence of Bluebeard. In general, this version is representative of other chapbook versions in its economy of style. The key elements are here as they are in Perrault. When fitting the story into a fixed number of pages, as chapbooks must usually do, for any elaboration something must be lost. So, the main deviation in the ending of this version, which accounts for the final three paragraphs, is bought at the expense of other standard hallmarks, such as the delay in seeing the brothers arrive:

Poor Fatimer [sic] had fainted, and was some days before she recovered; when [new page] finding herself so unexpectedly rich, she intreated [sic] her sister and two brothers never to leave her; and she also sent for her dear mother to live with her, and to share her fortune.

Under their advice, she had the bodies of the unfortunate ladies buried with the greatest solemnity.

And then, on condition that they paid just and liberal wages to their labourers, she very greatly reduced the rents of Blue Beard’s tenantry. She built and gave pretty cottages, each with large gardens, without rents, to all the industrious working families on her large estates; and in performing such acts of goodness and mercy, she passed a long life, beloved and respected by all who knew her (Dean & Son 1854–1856).

The illustrations are a feature and an attraction to buyers of chapbooks, frequently advertised by the publisher, so it is not unusual to see that the text also gives ground to such a large number of engravings. As has been said, the pictures tell the story in counterpoint to the text rendition of it. The economy of style keeps the chapbook versions like this one in close contact with the fairy tale and oral traditions: cause and effect are boldly juxtaposed, without embellishments. The wife cannot clean the key; the husband returns; he asks for the keys the next day. In versions that do embellish, as the one quoted below demonstrates, these moments become heightened. The wife attempts to clean the keys with all manner of things (a catalogue that includes at various times sand, brick dust, and emery, and often includes naming soaps by brand). The midcentury comic version by F. W. N. Bayley elaborated: “With soap, lime, and ashes / She works and she washes, / In puddle and pail, / But it will not avail: / In meal and in malt, / In brandy and salt!” She finishes by roasting and boiling the key, which “Defies all the forces of fire and water” (Wm. S. Orr & Co. [ca. 1842], 27). In some of these chapbook variations, Bluebeard does not return before night, allowing the wife and her sister Anne a longer frightful period of waiting. They may then spend all night trying to clean the key before giving it up as a lost cause, as in the following example: “They spent a great part of the night in trying to clean off the blood from the key, which was the only evidence of Fatima’s imprudence; but it was without effect. … Fatigued with their exertions they at last retired to bed: but the wretched Fatima, who could not sleep, lay ruminating on the awful scene she had gone through, and devising means for escaping the vengeance of her cruel husband Blue Beard” (Glasgow: For the Booksellers 1852, 10).10 Occasionally, escape is fatally delayed: “she therefore resolved to escape from this dreadful mansion as soon as the entertainment which was appointed for the next day should have taken place” (Printed for N. Hailes 1817, 62). In one version, the cat and mouse game of asking for the keys is itself protracted; Blue Beard may ask for them on the pretext of needing to dress (W. Walker & Sons [185–], 5).

The orientalism of the Dean & Son version is minimal; it exists in name alone (Fatimer/Fatima) and to some extent in the nature of the illustrations, which while showing a coach instead of an elephant and livery instead of black slaves, as is often the case, and calling Bluebeard’s blade a sword instead of a “scymitar,” still depict oriental balconies and a beturbaned Bluebeard. It is less usual for Bluebeard to involve others in his activities, as when he calls out to his slaves to bring him his sword, but their role is fleshed out in much greater detail in the stage versions, as the secondary cast of characters. The chapbook History of the Cruel Monster Blue-beard (J. Bailey [1812–1813]) uses this cast and the plot outline from the Colman and Kelly 1798 play, likely due to its popular 1811 revival. Bluebeard is “Abomelique,” the “barbarous Blue Bearded bashaw” with a servant named Shacabac who is included in his secrets and given a charmed talisman to place in the chamber; Fatima is sold to this husband by her corrupt father Ibrahim, as her lover Selim is not rich. When Bluebeard (Abomelique) is wounded by Selim, he is reclaimed by demons: “when a violent noise arose, and three or four infernal spirits were seen, who advanced to Abomelique, exclaiming his time was come; and the wound given by the youth had broken his charm which had hitherto preserved him from punishment, with these words they cast him into the furnace, which, with the infernal spirits and Blue Beard, sunk with a thundering sound, and vanished entirely from view” (J. Bailey [1812–1813], 17). This storyline is responsible for the chapbook illustrations, which show demons or lively skeletons and puffs of smoke pouring out of the chamber, as on the cover of S. Marks & Sons Blue Beard ([1876]).11

In orientalized chapbook versions it is not uncommon to begin by locating Bluebeard in Turkey: “In Turkey dwelt a wealthy man, / Whom maid and matron fear’d; / For frightful was his countenance,— / He wore a large blue beard!” (Samuel & John Keys [between 1873 and 1894]).12 Some even comment on the difference in marriage laws, as the [1812–1813] chapbook also does: “Though Turkish laws allow every man the liberty to have as many wives and concubines as he can support, yet Abomelique, so far from availing himself of that privilege, never had more than one wife at a time; and it was not a little remarkable, that out of 12 young and beautiful damsels, to whom he had been married, no one lived more than a few months and for the major part were reported to be dead in only a few weeks after their marriage; and their funeral conducted in so private a manner, that none of their relatives had any opportunity of examining their bodies, to discover whether their death was occasioned by ill usage” (J. Bailey [1812–1813], 4).

The daughter’s “vanity” is an issue in the Dean & Son example: “Among the guests, there were two sisters, daughters of a respectable widow, to whom Blue Beard paid particular attention; and this raised the vanity of the youngest so much, that she thought she should not object to become his wife” (1854–1856).13 This vanity, instead of the mere greed implied by Perrault, is a feature sometimes editorialized upon in the chapbooks. Whereas Perrault’s version leaves implicit that the courting is accomplished less by Bluebeard himself than by the show of his wealth and entertainments, the chapbooks focus instead on the younger daughter’s vanity: “Personal attentions, even although paid us by an ugly creature, seldom fail to make a favourable impression, and therefore it was no wonder that Fatima, the youngest of the two sisters, began to think Blue Beard a very polite, pleasant and civil gentleman, and that the beard, which she and her sister had been so much afraid of, was not so very blue” (G. Caldwell 1828).14 In some chapbooks, the mother also chastises her daughters for their prejudice against Bluebeard. An elaborate version of this vanity and prejudice is given in the N. Hailes miniature book, Blue Beard (1817), so that it seems curiosity is not to be the least of the wife’s failings:

Such however is the thought-less emulation of young ladies, that scarcely any thing pleases them so well as an opportunity of surpassing each other in the vain trapping of finery. …

There is no strength of understanding, or variety of knowledge, or goodness of heart in making a shew of these childish embellishments; but a fondness for them certainly proves that the person who is so much attached to them, has very little else to be proud of. Indeed, so far from being a recommendation to a person; this foolish propensity for gaudy attire makes the nearest approaches to manners and dispositions of the most ignorant of mankind.

In all the places where savages are found, there is the strongest partialities for useless finery. In the islands of the Pacific Ocean, and in other parts of the world where knowledge has not yet enlightened the inhabitants, the uncivilized people decorate themselves with bits of glass, feathers, pearls, and shining stones. But they may be forgiven for this weakness; their minds have not been improved by instruction, and they have not art or science, or rational amusement to engage their attention.

But what can be thought of persons, who, surrounded by every allurement to useful and interesting employments, devote their minds to the decorations of dress: and who would foolishly think, that their glittering and fantastical ornaments give them superiority over the worthy and the wise? It would be advantageous to young folks to recollect, that so much attention to outward appearance betrays extreme vanity; and that vanity is the most degrading quality of the human heart, and the certain source of general contempt (Printed for N. Hailes 1817, 12–16).15

Whether the irony is intentional or not (and presumably it is not), lavish descriptions of the sumptuous castle and its trappings immediately follow this lesson. The same strain is visible even late in the nineteenth century, in the McLoughlin Bros. pantomime toy book Blue Beard [189–]: “Poor, foolish Fatima, you see, flattered herself that whatever might have been the trouble with his former wives, she would know how to manage him, and by means of his seemingly great affection for herself, would be able to retain her power over him forever. We shall see in the end, how miserably she was deceived in these notions, and the heavy price she was obliged to pay for her vanity and love of display” ([189–]).16

Instead of blaming the wife’s curiosity outright, the Dean & Son chapbook gives the wife some nearly reasonable motivation: she “thought it strange” that she should not be allowed to go into this closet, and this is the cause of her final temptation. The suspenseful pause on the threshold is another of the heightened moments that prove irresistible to many chapbook publishers and later embellishers of the Bluebeard story. In some chapbooks, Anne tries to dissuade her sister at the door (one illustration shows Anne trying to pull her sister’s arm away from the keyhole), to no avail.17 As discussed in the next chapter, Anne’s role here takes a significant shift, as she becomes the pantomime “villain” and betrays her sister.

Chapbook illustration. From W. Davison. 1808–1858. History of Blue Beard. Alnwick. Courtesy of The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

Other wives are indignant that they should not be able to go into the chamber. In one late verse edition, Fatima and Anne both convince each other, after a week of obedience, to transgress: “They looked, and they longed, and they fidgeted round, / And whispered, ‘We’re not to obedience bound; / If a husband has secrets, it can’t be a sin / For a good wife to know them’—and then they went in” (McLoughlin Bros. [189–]). Often, it is in the form of the following assumption: “Thinking as Blue Beard was so very fond of her that he would easily forgive her for disobeying him, she, with a trembling hand, applied the key to the lock, and opened the door” (G. Caldwell 1828, 12).

Another moment often embellished is the time given to the wife. Perrault’s “half a quarter of an hour” has given all English translators some trouble: in Dean & Munday’s Blue Beard (1821), it was given as “the eighth part of an hour,” while in Thomas Nelson’s The Story of Blue Beard (1900) it was: “seven and a half minutes exactly, and not a moment longer!”18 The chapbooks reflect the difficulty of translating the time and range most commonly between five, ten, or fifteen minutes. But to heighten the dramatic moment, a countdown emerges in some chapbooks, so that the wife is given first a quarter of an hour. When that expires, she asks for five minutes more, then two, then one …; as each limit expires, the threat of death is again raised. Bluebeard is even complacent. She is completely in his power, so what is five more minutes?19

Another “untranslatable” expression that results in chapbook variations refers to the military ranks of the brothers. Perrault’s “dragoon” and “musqueteer” do not translate well, so in English chapbooks they are officers “dressed in regimentals.” Instead of purchased captains’ commissions, as in Perrault, they are in one American version of 1797 awarded “colonel’s commissions” (John M’Culloch 1797).20

While the variations in time are understandable, given the difficulty of translating the idiom, it is not in translation that the chamber becomes the “Blue Chamber” or the “Blue Closet” in many chapbooks, but in Colman and Kelly’s melodrama (complete with blue fire).21 The Colman and Kelly drama definitely referred to the Blue Chamber and underscored the point with liberal use of blue smoke during and at the end of the production. As early as Tabart’s fifth edition there are illustrations in chapbooks captioned: “The Blue Chamber” (Tabart & Co. [1804 or 1805]).

Given that the readership of these chapbooks was children, a fact reflected in titles such as: The History of Blue Beard: An Entertaining Story for Children, and in use of nursery book or “Good Child” or “Juvenile Library” series titles, or “A Keepsake for Children” (London: Printed for the Booksellers [18–]), it is perhaps surprising to what extent the gore of the chamber is detailed, as it almost always is. In Samber’s translation of Perrault’s tale (1729), the description is given as follows: “But she could see nothing distinctly, because the windows were shut; after some moments she began to observe that the floor was all covered over with clotted blood, on which lay the bodies of several dead women ranged against the walls. (These were the wives that the Blue Beard had married and murder’d one after another.)” In chapbooks, the opportunity for embellishment is irresistible: “She found herself amidst the severed limbs and mutilated bodies of her husband’s former wives! The scene was frightful! Her own future condition, she immediately thought, might add to these dreadful objects! Her blood chilled! Her very hair rose upon her head! Nor was her terror diminished, when she saw upon the wall these awful words: ‘The fate of broken promises and disobedient curiosity.’” (Printed for N. Hailes 1817, 57–58)22 Perhaps it is as a result of captioned illustrations, as much as by the Colman and Kelly 1798 drama that used this device,23 that the contents of the chamber are rendered literally legible. The wife’s realization (“Her own future condition, she immediately thought, might add to these dreadful objects!”) is spelled out: “she saw upon the walls these words: The Reward of Disobedience and Imprudent Curiosity” (Peter G. Thomson [n.d]). In one case, the heads themselves are each labeled: “An inquisitive wife” (Printed for J. Harris 1808).

In some chapbooks, there is an attempt to render a story of origins, the answer to the question: What did the first wife see when she looked inside? The originary story that circulates through chapbooks is surprisingly consistent: “Blue Beard’s first wife was a bold-spirited woman, with whom he quarreled soon after marriage; and having in the heat of his anger murdered her, he concealed her body in this blue closet. The rest of his wives, who, like Fatima, could not refrain from indulging their curiosity, he had killed for acting contrary to his express commands; and the key had always betrayed their disobedience” (W. Walker & Sons [185–])24 The tradition of originary myths for Bluebeard’s chamber is now long and rich, but it is interesting to note that at its heart is always an unruly woman. Like Lilith, Eve’s precursor in Eden, Bluebeard’s first wife’s transgression was to be “bold-spirited.”

The last paragraphs of the Dean & Son version tell of perhaps one of the most interesting changes made in the nineteenth century to the Perrault version. In Perrault, the wife inherits Bluebeard’s fortune and dispenses it to advance the situation of her siblings and herself: the brothers are bought captains’ commissions, she and her sister Anne are dowered and marry. The monetary nature of the end of Perrault’s story has been attributed to his lawyerly mindset. But it is still in starkly rapid contrast to the attentive descriptions of Bluebeard’s lavish wealth and what it has bought him. In many Victorian versions, however, the details of how his wife proceeds once Bluebeard is dead, and how she then spends her fortune, are carefully rendered. But in contrast to the descriptions of lavishness (the “pomp and ceremony” of the wedding alone is sometimes given a page or two), the wife’s disbursement of funds is much more charitably directed. Frequently, as in the Dean & Son version provided above, the house is opened to public view, and thereby a sort of exorcism is performed. In some cases, it is described in very practical terms: “The fatal closet underwent a complete repair, which removed every trace of his barbarity” (J. Innes [1830?]). The laws, rights and protections of community are restored through public rites, exorcising Bluebeard’s anti-social secrets.25 In these versions, there is often no mention of remarriage, but rather she becomes a “respectable widow,” like her mother, with whom she may now live. Her family still benefits from Bluebeard’s death, but does so by living together and behaving as good landlords to the tenantry. A long variation on this theme is given in the chapbook History of Blue Beard:

All those horrid murders which had been committed by Blue Beard, were unknown to his domestics, on whose credulity he imposed by falsehoods, which they had no means of detecting: Fatima and her brothers thought the most prudent way to act was to assemble them together, and then disclose the wickedness of their late master.

It was now that each of the domestics could recall to their memory the bitter sigh and heavy groan that had struck upon their ears, shortly before the wives of Blue Beard disappeared; yet the artful, and seemingly meek behaviour of their master, contrived to lull all suspicion of the atrocious fiend. It was with some difficulty that they made themselves believe that they had been serving this demon in human form.

By the directions of Fatima, her two brothers conducted all the servants to the dreadful scene of her husband’s cruelties; and then showing them his dead body, related the whole occurrences which had taken place. They all said that his punishment was not adequate to what he deserved, and begged that they might be continued in the service of their mistress. As Blue Beard had no relations, Fatima was sole heir to the whole of his immense property; and mistress of the castle; in the possession of which she was confirmed by the laws of the country.

Immediately after the interment [sic] of the dead bodies, the company retired to Blue Beard’s private chamber, and on examining his papers discovered a sealed packet, which, on being opened, contained a sheet of parchment, on which was written the names of his murdered wives, with the addresses of their nearest relatives, and at Fatima’s request, her brothers, with as much delicacy and feeling as the distressing and mournful tidings would call forth, wrote to them a full explanation of Blue Beard’s conduct, and a detailed account of the circumstances which led to the tragic termination of this infamous character.

Soon after this, Fatima gave a magnificent entertainment to all her friends, where happiness was seen in every face; and on this occasion the poor, who were assembled for many miles round, partook most liberally of her bounty. Though possessed of riches almost inexhaustible, Fatima disposed of them with so much discretion, that she gained the esteem of all who knew her. She bestowed handsome fortunes on her two brothers, who were the means of saving her life; and to her sister who was married about twelve months after, she gave a very large dowry.

The beauty, riches, and amiable conduct of Fatima, attracted a number of admirers; and among others, a young nobleman of very high rank, who to a handsome person, added every quality calculated to make a good husband; and after a reasonable time spent in courtship, their marriage was celebrated with great rejoicings (Glasgow: For the Booksellers 1852, 14–15).

If it is perhaps unseemly for Bluebeard’s wife to profit so directly from his death, it certainly seems to be the case that she cannot be seen to profit so personally from her disobedience. One verse moral (directed to “Young Ladies”) stated: “‘Inquisitive tempers / To mischief may lead; / But placid Obedience / Will always succeed’” (Printed for J. Harris 1808).26 Frequently it is moralized that the happy ending came at great cost: “But though his kind treatment soon made her forget Blue Beard’s cruelty, she never forgot, that to her own indiscreet and foolish curiosity, she owed the terrible trial through which she had passed” (Pott & Amery [n.d.]); “Although the kindness of her second husband was equal to Blue Beard’s cruelty, she never forgot that her own foolish prying was the cause of the terrible danger she had so narrowly escaped” (Thomas Nelson 1900, 119). The connection with her inheritance (rather than the kind treatment of a later husband) is most clearly made in the following formula: “Fatima used with discretion and liberality the wealth of which she had become possessed: but she never forgot that she should ‘keep her promise; obey those who were entitled to her submission; and restrain her curiosity within moderate bounds’” (Printed for N. Hailes 1817).

Bluebeard does not entirely escape the moralizing trend either. The Miss Merryheart series of Dean & Son (printed by McLoughlin in America) all note that Bluebeard’s conscience is awakened as he is killed: “Sudden as the attack of these brave men was, it was not quicker than the awakened conscience of this cruel man. All his deeds of blood instantly presented themselves to his mind. The image of every unhappy being whom he had destroyed, appeared to his imagination, and embittered the misery he now endured. After a few convulsive struggles, he fell back and expired” (Dean & Son [ca. 1860]).27

This moment is heightened in Hailes’ 1817 miniature book version, whose castigation of the youngest daughter’s vanity has already been quoted above, and is a lengthy dying speech from Bluebeard worthy of the stage. Still, in doing so, he nonetheless manages to heap further blame on his would-be victim:

The monster had yet sufficient life to speak: he raised himself on one arm; and looking on them all, thus spoke: “I am at last justly punished. By the splendour of my riches, I have induced many a beautiful woman to become my wife; but as soon as I discovered any deviation from truth, or disobedience to my will, she suffered death. I put Fatima’s veracity to the test by obtaining her promise that she would not open the door of the blue closet; and by leaving the key with her, she broke her word; and the key, which has the property of preserving the stains of blood until it be rubbed with a peculiar oil, afforded the evidence of her guilt. By the same means I knew that she had disobeyed my desire. These two faults incurred my revenge. She has had but a narrow escape: yet I hope she will in future never break a promise; disobey those to whom she had promised submission; nor give way to the impulse of curiosity.”

He grew faint, and having uttered a few prayers for forgiveness, he fell back and expired (Printed for N. Hailes 1817, 85–87).

In an example from the late eighteenth century, quoted above as giving “colonel’s commissions” to the brothers, the title “with morals” entirely understates the case. Perrault’s morals are given, which is not often the case in chapbooks, but in addition, an extra moral is provided at the end of the tale itself: “The curiosity of Blue Beard’s wife had well nigh cost her her head; and this disposition will bring all of all sexes, who indulge it beyond the bound of prudence, into difficulties they can hardly escape from. Yet the reader is desired to take notice that there are two species of this turn of mind: the one commendable, when it leads to knowledge; the other blameable, when it only serves to gratify an idle inquisitiveness” (John M’Culloch 1797, original italics). It is unusual both in that the additional moral includes both sexes in its caution and in distinguishing between good and bad uses of curiosity, rather than castigating curiosity altogether.

Although it was common for chapbooks to be pirated and copied wholesale, a surprising discovery emerges from a survey of so many variations on the Bluebeard theme: a consistent “alternative” translation from Perrault to the dominant two by Robert Samber and by G. M. It has some of the characteristics of the Samber translation, using the term “collations,” for example, and also several of the hallmarks of G. M.’s translation (“half a quarter of an hour”; “bawled”; “scimitar”) blended together. But in addition, there is a series of hallmarks of this alternative version that are not present in either Samber’s or G. M.’s translation and that are nevertheless astonishingly consistent. In these, Bluebeard entreats his wife to invite her friends “and to treat them with all sorts of delicacies”; he warns she must not enter the chamber, “nor even put the key into the lock, for all the world”; he departs only “after tenderly embracing her”; and when she transgresses “she determined to venture in spite of everything.” When she tries to recover from her shock at seeing the chamber’s contents, she goes to her room “that she might have a little time to get into humour for amusing her visitors”; she tries to pretend she is “transported with joy” at her husband’s unexpected return, and when he asks for the keys he tells her to bring them “by-and-bye.” When he sees the key is bloody, he concludes that she must enter the chamber by saying “Vastly well, madam”; and the two officers who enter are “dressed in their regimentals” (Cunningham 1889).28

Chapbook illustration, the chamber. From E. Billing. 1839–1849. History of Blue Beard. London. Courtesy of The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

The woodcuts and engravings that adorned chapbooks were often rough and recycled, but whatever the quality they seem to be a necessary component of the chapbook. The number and type of illustrations formed a major advertising point in the competitive publishers’ lists. As Harry Weiss wrote: “Regardless of the crudeness of chapbook illustrations, they have a certain charm and quaintness and seem to be an integral part of the chapbook itself” (1942, 5).29 They were integral, in other words, even when the illustrations were barely connected thematically to the text. As has been said, the illustrations were often a form of “filler” only tenuously linked to the subject at hand. This can lead to amusing results in Bluebeard’s case. In some instances, such as J. Swindells [1830?], a couple of the illustrations depict a man with no beard. In the case of J. Pitts [1810?], Bluebeard is depicted properly bearded, except that in this case the text has described him as “clean-shaven,” perhaps to accompany an earlier illustration.

Chapbook illustration. From J. March. [1864–1875]. Blue-Beard. Courtesy of The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

It also seems that the illustrations, particularly the frequently repeated one of the near-execution, were an integral part of their first production, in Charles Perrault’s manuscript edition of Contes (1695). Ségolène Le Men neatly situated the headpieces and composition of that first illustration of “La Barbe Bleue” and the resulting print edition (1697) within the emblematic tradition, which again argues how integral the illustrations are to the tale: “The organization of the illustrated page shared by [Perrault’s] manuscript and the [1697] edition may suggest the reason why Perrault’s tales were illustrated in the first place. Tales belong to an emblematic tradition, as do fables. … Emblems are a mixed medium rooted in the interplay between the concrete and the abstract, involving both text and image” (1992, 21).30 Le Men also indicated that as “Each period added new pictures to the original group of single illustrations” (37), so the text was ultimately “evicted.” In many chapbooks, this “eviction of the text” has already begun, in fact, as the illustrations grow in size and number to displace the text. The publishing restrictions (for cost and distribution) on chapbook size and page numbers dictate that the one must give way as the other usurps the limited space. More than merely decorative and perhaps, as Le Men argued, reminiscent of “pictorial pedagogy” (22), the chapbook illustrations of Bluebeard come to be repetitions of the same scenes from the text, to the point where they come to be the requisite iconography of the story.31

The Bluebeard chapbook illustrations are a series of “set pieces”; certain iconic postures repeated over and over again. The very first illustration, in Perrault’s manuscript version of 1695, is in two forms: frontispiece illustration and in-text illustration (headpiece).32 As Le Men described, Bluebeard is first recalled in the frontispiece illustration that draws visual elements from all the stories in the Contes in order to function as a rhetorical memory device. Bluebeard is recalled in “The carefully closed door and its visible keyhole” of the room in which “Mother Goose” is telling stories (the very door on which the sign “Contes de mamere loye” [sic] is nailed). The headpiece illustration derives directly from the story: “In Bluebeard, the picture is evenly split into two parts in order to show two settings and actions simultaneously: Bluebeard and his wife vis-à-vis the galloping horsemen; the inside vis-à-vis the outside of the castle” (1992, 32). Even the depiction of the near-execution is due to formal requirements: “the imminent danger and not the crime itself [is] pictured, as baroque pictorial conventions would dictate” (32).33

In keeping with this first illustrated headpiece, the illustration that most often represents the Bluebeard tale on chapbook covers and frontispieces is this moment of near-execution, except that it is now featured alone, while the imminent rescue is its own set piece.34 Baroque pictorial conventions may have dictated this moment to some extent, but, in addition to being suspenseful and dramatic, it also depicts erotic violence. In the chapbook illustrations focusing on the wife’s near-execution, Bluebeard stands over her, scimitar drawn. His wife is helpless and imploring, her head at or below his waist, pulling herself away as Bluebeard grabs and pulls her hair. It’s not just Bluebeard’s power, cruelty, and secrets being depicted, but sadistic, erotic violence. Even in comic versions such as F. W. N. Bayley’s, the overtones are made clear: “Oh! hadn’t a fair lady better be dead / Than be dragged down stairs by the hair of her head?” (Wm. S. Orr & Co. [ca. 1842], 41).35 This, rather than the moment of women discovered in the chamber, is what is on the covers of Bluebeard chapbooks, and it is obviously connected to the corpses in the chamber.

The requisite illustrations grow through chapbook repetition to include standard “set pieces” for: the courtship (and/or the wedding procession), the giving of the key, the chamber, the call for rescue, the near execution, the killing of Bluebeard. The illustrations are sometimes captioned, and these captions and the order of illustrations (the first illustration going to the near-execution) tell the story a second time. The illustrations in The History of Blue Beard (W. S. Johnson 1850) are, with a couple of omissions, exactly the same illustrations as those in J. Innes [1830?] but with the addition of another on the first page: the near execution, as Bluebeard holds her by the hair and the brothers rush to the rescue. The others are captioned as follows: “Ann waving her Handkerchief to her Brothers at the time Blue Beard was going to murder Fatima”; “The First Visit of Ann and Fatima to the Castle”; “The Procession of Blue Beard after his Marriage”; “Blue Beard intrusting [sic] Fatima with his Gold and Jewels”; “Imprudent Curiosity of Fatima to see the Blue Chamber”; “Blue Beard asking how the Blood came on the Key”; “The Brothers Killing Blue Beard, to save their Sister.”

Chapbook illustration. From W. Davison. 1808–1858. History of Blue Beard. Courtesy of The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

The “beautiful cuts” of the chapbooks are gleefully rendered in the vision of the chamber, which has its own standard illustrations, but nevertheless also a surprising range of diverse elements. Despite an established readership of children, the contents of the chamber are usually rendered in all their gory detail (often colored by child laborers) liberally colored in swathes of red. The standard arrangement is: the wife reacting to the sight in horror, throwing her hands up and shielding her eyes; the key dropping to the floor in midfall; the bodies of several women lying or hanging or both, with and without their heads. Blue Beard [1861] shows an engraving depicting five headless corpses, eerily standing up, and six female heads on the floor, with blood. The description here is given with gusto: “She stood in the midst of blood, the heads, bodies, and mangled limbs of the murdered ladies strewed over the floor” (J. Bysh [1861], 4).

The key is usually oversized throughout these illustrations, and in the illustrations of the bloody chamber it is an integral and necessary element. In many cases, the key is visible in midfall; the illustration captures the moment of looking (discovery), and simultaneously the act of dropping the key that will result in the other discovery. In some chapbooks the key is depicted as broken on the floor; this was a prop resulting from stage adaptation, where a spot on a key would not be readily visible to the audience, but also helpful to the gradual bowdlerizing of the chamber in which there is first no blood, and finally no bodies. Instead, in response to the Colman and Kelly play, itself a gothic product, the contents of the chamber in illustrations become more lively and “supernatural”; skeletons appear alive, puffs of smoke issue from the room, and even demons fly about.

The Death of Bluebeard visually mirrors the chamber in its depiction of a corpse, balancing and redeeming the tale’s violence with Bluebeard’s own murder. Printed for J. Harris, successor to E. Newbery. 1808. Blue Beard, or, The Fatal Effects of Curiosity and Disobedience, Illustrated with Elegant and Appropriate Engravings. Courtesy of The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

There are, of course, a few examples of editions with no bodies in the chamber at all. A late version, Blue Beard and Puss in Boots acknowledges that the child reader may have some qualms with the material in its dedication: “To Siegfried. / If the tale of Blue Beard / Should make you afeard, / As the time nears for bed! / “Puss in Boots” read instead!” (J. M. Dent & Co. 1895). By 1900, there is a giant key, dripping blood, pictured on a back cover of [Ten] Favourite Stories for the Nursery, with Numerous Illustrations (Thomas Nelson 1900), and not only are the chamber contents not depicted (the wife is shown from behind, as she looks in), but also the death of Bluebeard occurs “offstage”; the picture shows the brothers leaving him for dead, one stepping away from the body, the other already as far away as the doorstep.36 The violence, like the chapbook phenomenon, has passed.

The chapbooks, “orphaned” and “rude” as they may have been, were the vehicle by which Bluebeard traveled across the British Isles and America, just as his counterpart was traveling across Europe. These chapbooks provide vivid evidence that while tastes in children’s reading may not have changed, the publications marketed for children certainly have. The fairy tale thrived in this blunt format, and the illustrations were integral to its continued popularity. By sheer repetition, the orientalism introduced by the 1798 melodrama also took permanent hold, and it was a Turkish Bluebeard and a wife named Fatima who were most often projected to the reader of these chapbooks. The chapbooks also, importantly, blurred the distinctions between readerships; fairy tales were on a path to becoming children’s fare, but chapbooks were widely read and not only by children. Furthermore, the memorable influence of childhood reading on future adult authors and artists, like Charles Dickens, also contributed to Bluebeard’s hold on the English imagination.