“YOU OUTRAGEOUS MAN!”

Bluebeard on the Comic Stage

In the dramas of the early decades of the nineteenth century, Bluebeard took his cue from the Colman and Kelly production, infusing contemporary chap-books with imagery and characterization from this popular stage production (1798) and its popular revivals.1 The stream of chapbooks that had taken their direction from Perrault translations was decidedly diverted. Here, Bluebeard is an oriental grotesque; his wife is named Fatima; she is sold by her mercenary father Ibrahim to the “three tailed Bashaw”2 and rescued by her true love, Selim, along with her brothers and her sister Anne. Such was the story set by Colman and Kelly, illustrated from the theatre by R. Cruikshank, and thriving in the popular ephemeral chapbooks. Not surprisingly, therefore, this was the story told repeatedly from the stage, and in the first half of the nineteenth century in particular, the Colman and Kelly production was the persistent intertext with which these other works were in dialogue.3 But after 1866, a rival “masterwork” entered the arena in Blue Beard Re-Paired; a Worn-Out Subject Done Up Anew, adapted by Henry Bellingham from a French comic opera by two masters of the form, Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy. The plot is vastly different from that of Colman and Kelly’s melodrama, the oriental cast is nowhere to be seen, and by 1868 the work had premiered in America, where, as in London, it remained popular throughout the last decades of the century, thriving in a climate encouraging to operetta.

An allusion in all types of Bluebeard dramas is Shakespeare’s Othello, also featuring a wife-killer, a man “turned Turk.” Already echoed in Robert Samber’s English translation of Charles Perrault’s fairy tale, the dramatic intertext was much more thoroughly brought to bear in stage representations of the Bluebeard tale, newly set in Constantinople or Baghdad, throughout the nineteenth century, creating comic disjunction between the tragedy of Shakespeare’s play and the burlesque use made of it.

In the early decades, in light of extant records, it seems that audiences on both sides of the Atlantic were very pleased to see Colman and Kelly’s drama itself. But with such an influential and “complete” precursor in the melodrama, there was an irrepressible upsurge of burlesque that began with making fun of this major intertext, so that the comic form in one way or another dominated the nineteenth-century dramatic representations of Bluebeard, whether Turkish (as he most often was) or not. In direct contrast to the trend on the German stage,4 serious stage renditions of the Bluebeard story in England and America were almost entirely absent, save for a few of the amateur or parlor entertainments that act out Perrault’s tale with little or no attempt at comedy.

Never presented on the English stage, Ludwig Tieck’s five-act gothic drama Blue Beard was translated into English by John Lothrop Motley and published in two issues of the New World (1840). Motley was a writer who had studied in Germany and had already published translations of German works (of Schiller and of Novalis), both in 1839 for the New Yorker, and had reviewed Goethe for the New York Review (1839). The advertisement above the translation described Tieck as “the most popular living author of Germany” whose lighter pieces were very well known; the translation was presented as a “specimen” and an “experiment” to see if it would amuse the American reading public. The subject was introduced as one of a “Fantasie” series: a dramatized nursery play, which was “chiefly entertaining as being the vehicle for the author’s delicate humor, satire, and romance.” Tieck’s play also demonstrates the influence of Shakespeare, whom Tieck had translated into German, but reveals the German writer’s poetics of “nonsense” through making foolishness, rationality, and the ability to orate actual topics for the play’s banter, and by making the Fool (Claus) wiser than the fools who employ him. The central plot concerns Agnes von Friedheim who is married to Hugo von Wolfsbrun, also called Bluebeard, by her brothers who desire a wealthy match. When she takes up residence there, with the gothic crone Matilda and her sister Anne (herself pining for her love Reinhold), she enters the chamber. The play does not show the moment of discovery, but revels in the description days after the fact. Anne notices that Agnes is behaving oddly and compels her to tell the story. Hugo, returning early, unleashes invective against his wife as a daughter of Eve: “Accursed curiosity! … The sin of the first mother of the human race has poisoned all her worthless daughters.” While Agnes begs for mercy, he is unflinching: “You abominate me now.” She is rescued by her brothers Simon and Antony, thanks to the former’s dream prophecy. Subplots, which are extensive, concern the third brother Leopold and his elopement with Bridget, the sister of Reinhold and daughter of Agnes’ godfather Hans von Marloff. There is a bevy of comic servants to offset the gothic drama.

The other possible exception to comic dramas on the subject is The Female Bluebeard, or, The Adventures of Polyphemus Amador de Croustillac by Thomas Higgie (first produced with some modifications in 1847 as The Devil’s Mount, or, the Female Bluebeard).5 The play uses the Bluebeard story for the eponymous Female Bluebeard, reputed to be wealthy, to have been a widow three times already, and to have turned to piracy. The story is set in 1685 and is a pirate story using Caribbean settings and characters to develop a love story of historical political intrigue and the necessity of disguise. Despite the use of Bluebeard’s name and its interest as an early example of the “lady Bluebeard” label, it is anomalous as a serious drama on this subject.

By contrast, comic renditions of “Bluebeard” are abundant and fall into three major subcategories: harlequinade and pantomime; extravaganza and burlesque (including opera bouffe); and amateur or parlor plays for home entertainment (frequently as “children’s” theatre). Whether amateur or professional, burlesque remained the dominant tone until the major twentieth-century Bluebeard operas.

According to R. J. Broadbent, the French play called Barbe bleu on which Grétry based his Parisian opera in 1789 (which, as has been discussed, inspired Colman and Kelly), was a harlequinade to begin with: “‘Blue Beard’ was first dramatised at Paris, in 1746, when ‘Barbe bleu’ was thus announced: —Pantomime— representée par la troupe des Comediens Pantomimes, Foir St. Laurent. It was afterwards dramatised at the Early of Barrymore’s Theatre, Wargrave, Berks., and in 1791. After that the subject was produced at Covent Garden Theatre as a Pantomime” (Broadbent 1901, 204).6 By 1791, when Bluebeard, or, the Flight of Harlequin was staged at Covent Garden, the concept of a harlequinade was already very familiar to English audiences, who had enjoyed pantomimes and harlequinades for more than a century,7 and the genre had already spawned acknowledged masters in John Rich (at Covent Garden) and his rival Garrick (at Drury Lane), as well as public battles between the theatres for pantomime’s lucrative ticket sales.8 The precedent for using “Bluebeard” as a harlequinade in England had thus been set, but after Colman and Kelly’s Blue Beard (produced, as it says in the preface, “to supply the place of a Harlequinnade”), the traditional Christmas and Easter pantomime9 and harlequinades take on the eastern cast as well. In 1811, during the popular revival of the Colman and Kelly production, Harlequin and Blue Beard burlesqued it, turning each of Colman’s characters into traditional harlequinade figures.10

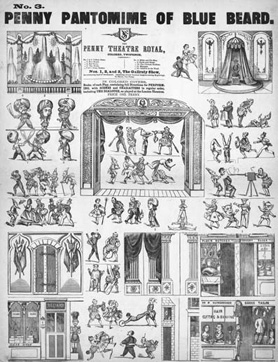

This Penny Pantomime sheet from London (ca. 1870) shows all the character transformations and set pieces from pantomime into harlequinade. From Penny Pantomime of Blue Beard. [1870?]. Courtesy of Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library.

The harlequinade in England, as elsewhere in Europe, initially took its form from the Italian Commedia del’Arte, which used a number of stock figures, masked, in a “dumb show,” accompanied by music. The term harlequinade (at this period in England it described the major portion of a pantomime) draws upon the figures from the Commedia, which in England devolved into four key players: Harlequin, the hero, able to do tumbling and direct the stage spectacles to appear as if by magic; Columbine, his lovely partner or a maid;11 Clown, the machinating and gleeful menace, derived from the Italian Scaramouche figure, or servant; and Pantaloon, who became on the English stage an old man, never able to catch the couple he pursues and who is often described as having an “ambling gait”.

Initially, the harlequinade elements were interwoven throughout the classical subject, as a continuing love story between Harlequin and Columbine, interspersing the unrelated action of the main story. But during the eighteenth century, the English pantomime structure changed to become a brief opening (usually based on a classical subject, fairy tale, or other universally known story), followed by a transformation scene that then initiates the harlequinade proper, using the same characters in order to resolve conflicts begun between them in the opening.12 The structure and relationship of the traditional double-plotted harlequinade/pantomimes of the early nineteenth century were helpfully described by J. R. Planché, himself a popular and prolific author of burlesque extravaganzas (including Blue Beard, 1839). It is interesting to note from his generic description how easily the Colman and Kelly dramatic structure (the old father, the poor rival suitor, and servants) befits the pantomime genre to which it so quickly adapted:

A pretty story—a nursery tale—dramatically told, in which “the course of true love never did run smooth,” formed the opening; the characters being a cross-grained old father, with a pretty daughter, who had two suitors—one a poor young fellow, whom she preferred, the other a wealthy fop, whose pretensions were, of course, favoured by the father. There was also a body servant of some sort in the old man’s establishment. At the moment when the young lady was about to be forcibly married to the fop she despised, or, on the point of eloping with the youth of her choice, the good fairy made her appearance, and, changing the refractory pair into Harlequin and Columbine, the old curmudgeon into Pantaloon, and the body servant into Clown: the two latter in company with the rejected “lover,” as he was called, commenced the pursuit of the happy pair, and the “comic business” consisted of a dozen or more cleverly constructed scenes, … Again at the critical moment the protecting fairy appeared, and, exacting the consent of the father to the marriage of the devoted couple, transported the whole party to what was really a grand last scene, which everybody did wait for (Planché cited in Broadbent 1901, 172–73).

It can be safely assumed that the Blue Beard, or, The Flight of Harlequin at Covent Garden in 1791 followed this form, as most likely did Harlequin and Blue Beard (1811). But the pantomime changed again, even before the general use of speaking parts, in the 1820s and 1830s. Writing “On Pantomime” in 1817, writer Leigh Hunt praised pantomime for being so “real” (84). Writing again in 1831, he lamented that pantomime had devolved into “gratuitous absurdity without object.”13 One of the major changes in the interim had been the “ballooning” of the brief opening into a play of equal length as the harlequinade and sometimes even longer.14 Although acknowledged masters in each of these roles received high praise and pantomime was consistently bankable entertainment, it had its detractors. Pantomime was low brow, and its slapstick pandered to crowds. While it remained a mute performance (set to lively music) it retained some of the best qualities of good acting performances. It remained a dumb show to get around restrictions on the minor theatres imposed by the patent theatres, until the patents were repealed and restrictions lifted by the Theatre Act of 1843. In 1830, a “speaking prologue” had been introduced, but as R. J. Broadbent wrote in 1901, pantomime “pursued the even tenour of its way” (220) until the mid-nineteenth century.15

The shift from melodrama (represented by Colman and Kelly’s production)16 to pantomime as a means of representing this fairy tale is significant and no doubt has many causes beyond simply the desire to mock a dominant precursor. Both melodrama and pantomime (especially pantomime, which reliably includes the rough treatments of Clown and Pantaloon and even stage murders) are “psychologically escapist” as Michael Booth noted, but they are also fundamentally opposed:

The governing spirits of the Regency harlequinade were misrule and anarchy: the freedom to commit amusing capital crimes and set law and authority at nought was bestowed abundantly upon Harlequin and Clown. Thus the harlequinade was, like melodrama, psychologically escapist, offering audiences a release for sadistic impulses toward cheating, tricking, larceny, cruelty, wanton destruction, violence, and rebellion. Melodrama, however, idealized morality, revered the aged parent, rewarded virtue and punished vice; pantomime satisfied different desires and did the exact opposite. The same audiences enjoyed both genres, and both found common ground in a general hostility toward constituted and inherited authority. In melodrama this was largely a matter of class conflict, but in pantomime the same hostility manifested itself in vicious treatment of an oppressive father-figure, Pantaloon, and in his watchman or policeman surrogate (1976, 5.5–6).

By 1901, Broadbent could call Bluebeard “another familiar Pantomime subject” (203). Certainly there are a number of extant plays that indicate that the familiarity was warranted. In addition to the two already referenced, a good number of pantomimes called Blue Beard survive.

John Morton’s pantomime Harlequin Blue Beard, the great bashaw, or The good fairy triumphant over the demon of discord! A Grand Comic Christmas Pantomime (first performed in 1854) is a sound illustration of the genre and of another principle used in it: the cross-dressed casting of several major parts, usually Sister Anne and Selim (but sometimes extending to other characters, such as “Mustiphustima,” the sisters’ mother, and even Fatima herself). The program in the printed edition of Morton’s play (The Acting Edition) included what was likely the playbill, giving an extensive description of the plot by scene. In Morton’s version, Rustifusti, the Demon of Discord, begins by inviting witches to help him fight the fairy. One of the witches, with his magic wand, summons an omen from a cauldron, warning that Bluebeard’s life is in danger from his new wife’s curiosity (wife number 22). It is revealed that the witch is in fact the fairy herself, and the other witches are also in disguise; the fairies keep Rustifusti’s wand. There is a comic scene in Bluebeard’s kitchen, largely comprised of physical humor (using hot pokers, a familiar instrument in the harlequinade sequences) and inventions out of control, culminating in an explosion. After pantomiming several routines in which Selim gets the upper hand on Ibrahim, Selim courts Fatima, with Ibrahim again trying to intervene and coming off the worse for it. Bluebeard enters (to the music of the now-ubiquitous march procession from Colman and Kelly) comically unsteady in his sedan chair and preceded by an hyperbolic brass band. These scenes are almost entirely mimed as the stage directions indicate. Bluebeard’s nursery is shown with twenty-one children saying good night to their new mother. At word that poachers are shooting Bluebeard’s game, he gives over the keys and enjoins Fatima not to open the blue chamber door. She immediately does, and amidst a number of special stage effects, including blue fire, one of Bluebeard’s deceased wives, her head under her arm, delivers the bad news. The key has turned blue, and Fatima begins miming her futile attempts to clean it; she is surprised by Bluebeard (who tiptoes up behind her), and they immediately enter into the threat-of-execution stage of the story. A large illuminated clock shows five minutes to twelve and forms part of the background to the scene of Sister Anne at the tower. There is the common to and fro between Anne and Fatima, with the equally common additional commentary usually found in this scene. In this version, Fatima chastises Anne for talking about the flock of sheep: “Anne, you’re a fool / All that great cry about a little wool!” Immediately after Selim kills Bluebeard, Rustifusti appears, changing the balance of power, but the Good Fairy also reappears and as the scene changes to Fairy Land, Rustifusti admits defeat and “like all Bad Geniuses in Pantomime, [goes] below.” The Good Fairy then effects the transformation of each character into their harlequinade counterparts.

Thus, we see a fairly representative use of the Bluebeard story in pantomime and harlequinade. The addition of supernatural characters to oversee the action and effect the transformation is typical. Here, it is Rustifusti versus the Good Fairy; in another, Despotino and his sidekicks are thoroughly trounced by Freedom and Britannia (Bridgeman 1860); elsewhere, Titania and Oberon team up against Bluebeard (Millward 1869).

In Charles Millward’s program, a new cast appears for the harlequinade, following the transformation. In most cases, however, the regular cast doubles up into the harlequinade characters and continues the comic business there. The comic violence done to Ibrahim continues throughout his role as Pantaloon; Abomelique becomes the Clown, to continue his attempts to thwart the “good” characters.

Cross-dressed casting, from which no doubt much physical humor derives, is endemic. In the example of Morton’s pantomime, both Sister Anne and Fatima (and therefore, at least initially upon transformation, Harlequina and Columbine) are played by male actors. Commonly, Sister Anne is played by a man. The comedy of the cross-dressed casting is further developed in pantomimes that elaborate on Sister Anne’s own frustrated wishes to marry, usually by trying to frustrate her sister’s relationship with Selim, marriage to Bluebeard, or both. Charles Millward’s pantomime (1869) is a good example of this humorous subplot: on overhearing Selim’s serenade to Fatima (on a banjo), she screams (no doubt comically), and then speaks in an aside to the audience: “ANNE: She talks of hiding him, to bill and coo, / I’d like to have the hiding of the two / (aside) Be still, fond heart, I really thought that he, / Instead of loving her, was ‘spoons’ on me” (7–8). Anne then tries to get Bluebeard to marry her instead of her sister and is rebuffed, but she is later proposed to by Shacabac. In Morton’s version, Anne is curious for her own sake, “because it’s woman’s mission to be curious” (1854, 14), while her sister is not at all inquisitive. However, often, it is Anne’s plan to encourage her sister into disobedience as part of her mission to gain a husband for herself, whatever the cost. As Sister Anne becomes more of a melodramatic villain, even quoting Iago at times, her own desire to marry leads her to hate her sister. Selim, in this version, is played by a female actor, as becomes very common over the course of the century. The same trend of cross-dressed casting continues in the amateur and home entertainments, with much being made of Sister Anne’s “maidenly coyness” for instance.

Finally, the use of pantomime as a vehicle for topical and social satire is ubiquitous. In addition to thematically related comments about Mormonism (Millward 1869),17 divorce court, and marital inequities, these pantomimes range far from the immediate subject matter to cast their topical allusions. While the deeds of public figures of the time are a matter now for historical research, others are self explanatory: “OBERON (aside): Were I a peer, would I, with offspring blest, / Make one child rich, and pauperize the rest? / Blest if I would—yet there are peers who do it” (Millward 1869, 18, original emphasis). Sometimes Sister Anne’s lookout sequence is used for this, as she names all manner of things that she can see coming, but which turn out to be illusions.18

In addition to the pantomime and harlequinade, nineteenth-century comic theatre sported many other forms, of which a dominant one was the burlesque. The forms were “overlapping” but all distinguished from the “legitimate” comedy which, until the Theatre Regulation Act of 1843 at least, was limited by law to the patent theatres. The minor theatres used music and song to evade the strictures of the Licensing Act, as seen with pantomime. Extravaganza always uses elements of burlesque. In the later decades of the century, burlesque and extravaganza became interchangeable to the theatre-going public due to the evolution of burlesque into a more heavy-handed form (as was decried in the state of pantomime). Burletta was another subgenre derived from an Italian comedic form, but whose definition in English was intentionally vague because of its use as a means of satisfying the Licensing Act.19

Because of their impact and influence on dramas that followed in their footsteps, as well as their iconic status in the genres they straddle, the two burlesques considered here in more detail are the fairy extravaganza by James Robinson Planché and Charles Dance: Blue Beard: an Extravaganza (1839), and the influential opera bouffe by Jacques Offenbach, music by J. H. Tully: Blue Beard Re-Paired (Bellingham 1866).

The dramatic negotiations with the legacy of the Colman and Kelly production took fixed burlesque form in 1839, in Blue Beard: an Extravaganza, by James Robinson Planché (another translator of Bluebeard and prolific writer of extravaganzas) and Charles Dance.20 In at least one edition it is subtitled: Very Far from the Text of George Colman.21 The play is the second in a long series of “fairy extravaganzas” by Planché that essentially created a new genre, for which Planché supplied more than twenty exempla. Planché’s extravaganzas forged a long and successful collaboration with Madame Vestris, the actress-manager of the Olympic theatre, who also acted the role of Fatima in the first production of Blue Beard, after the opening night was delayed for that purpose (Planché 1858, 237–38).

The extravaganza is an irreverent take on George Colman’s libretto, as indicated by its full title as given in the 1864 Lacy’s Acting Edition: Blue Beard: A Grand Musical, Comi-Tragical, Melo-Dramatic, Burlesque Burletta, in One Act.22 The setting is restored to France, and the play cites the legend of Gilles de Rais (although getting the details wrong). Planché noted in his Recollections: “‘Blue Beard’ was a great success. No longer ‘a very magnificent three-tailed Bashaw,’ as in Colman’s well-known and well-worn spectacle, he appeared with equal magnificence in the mediæval costume, the scene of the piece being laid, according to the original legend, in Brittany, during the fifteenth century, and was run through, not only ‘his wedding clothes,’ but the season” (1858, 237–38). The tyrant, while charged in the drama with being a necromancer like de Rais, is also named “Baron Abomelique,” even while the authors comment directly on the inaccuracy of having Bluebeard be a Turk: “The Melo-Dramatists of the past Century, converted Blue Beard into an Eastern Story, but every child knows that the old nursery tale, by Mons. Charles Perrault, is nothing of the sort. At Nantes, in Brittany, is preserved among the records of the Duchy, the entire process of a nobleman (the original of the portrait of Blue Beard) who was tried and executed in that city, for the murder of several wives, A.D. 1440. In accordance, therefore, with the laudable spirit of critical enquiry and antiquarian research which distinguishes the present aera, the scene of the Drama has been restored to Brittany” (Planché 1848, n.p.). Interestingly, though, the English reference also persists, as Abomelique swears twice “by Old Harry.”23 The matter is addressed within the play by having French names for the characters, reverting to the mother (instead of Ibrahim the father), and using the legend of de Rais to provide Bluebeard with legitimate cause to be gone from his wife. At the end of the play, the characters note for the audience’s benefit that the lack of Turkish influence was deliberate:

JOLI. But there’s another charge that may be made

By those who have not well the matter weighed;

They’ll say this can’t be Blue Beard; ask us where [sic] his

Horses, elephants, and dromedaries,

Real or stuffed?

FLEUR. To that the answer plain

Is—“Sir, the beasts belonged to Drury Lane,

And were but lent to Blue Beard, when—sad work—

They made him fly his country, and turn Turk.”

Our Blue Beard’s not a great Bashaw of three tails,

But a French gentleman of one—the details

Dished up, a l’Olympique, by the same cooks

Who for so long have been in your good books (1839, 28).

Fatima is named Fleurette, the military brothers are named “longue epee” (long sword) and “bras de fer” (arm of iron), Sister Anne is of course present, as is the mother Dame Perroquet. Fleurette is in love with Joli Coeur, who is thrown into Abomelique’s dungeon on her account. But once she realizes the degree of Abomelique’s wealth in rent rolls and that she may make a promising second match if he predeceases her, she forgets all about Joli Coeur, and is admonished for it by Anne. Bluebeard has married nineteen wives already and is looking to even the score. But despite claims to return Bluebeard to Perrault, the legacy of Colman and Kelly is the dominant intertext for the burlesque. The musical borrowings are thorough: it begins with the song from Blue Beard (“Twilight Glimmers”), and is followed by the “Grand March from the original Melo-Dramatic Opera of ‘Blue Beard’ composed by Michael Kelly”; Margot tries to usurp the heroine’s line “In pensive mood—” but is cut off by O’Shac O’Back, her Irish lover: “Don’t talk of moods or tenses!” They then sing their traditional duet (“Tink a Tink”) but all about his fondness for drinking and her disapproval (“I think, I think, I think that drinking is a sin!”). Fleurette finally sings “As Pensive I Thought,” and there is a trio “I see them galloping,” all taken directly from Blue Beard (1798). Abomelique has made “an ugly bargain, with a still more ugly sprite” (1839, 13). Fleurette’s decision to open the chamber is pragmatic: “And wherefore not, I should like to know? / If I’m to be the dame of this chateau” (16), and her response to the nineteen good women all with their heads under their arms (singing “nid nid nodding”), is equally unflappable, as she slams the door and goes about her business.

Planché’s play introduced the most extensive allusion to Othello to date and established the trend in Bluebeard dramas for the remainder of the century:

ABOMELIQUE. That key—

FLEURETTE. [aside] I feel I’ve not an hour to live!

ABOMELIQUE. Did an Egyptian to my Mother give. She was a fairy.

FLEURETTE. La, sir, you don’t mean it? Then would to goodness I had never seen it!

ABOMELIQUE. Wherefore?

FLEURETTE. He’s like the black man in the play.

ABOMELIQUE. Is’t lost? is’t gone? Speak! Is’t out of the way?

FLEURETTE. It is not lost; but what an’ if it were?

ABOMELIQUE. Ha! fetch it! Let me see it. If you dare!

FLEURETTE. Of course I dare sir; but I won’t before You promise me to spare poor Joli Coeur.

ABOMELIQUE. Fetch me that key, I say—my mind misgives.

FLEURETTE. There’s not a better natured fellow lives—

ABOMELIQUE. The key!

FLEURETTE. or on the horn can better play!

ABOMELIQUE. The key!

FLEURETTE. In sooth you are to blame.

ABOMELIQUE. Away! (21–22)

The allusion draws out the connection between Othello and Abomelique as “other,” with overtones of witchcraft. Othello successfully refutes the charge in Act I of Othello of having won Desdemona by enchantment, but when he tells Desdemona that his mother bequeathed him an enchanted handkerchief that would betray a spouse and cause a marriage to fail, he has by this point in the play begun to turn into the racist stereotype he was charged with. The “fairy” element of this fairy tale of Bluebeard has always been the enchanted key, and the English translation early introduced the notion that it was given to Bluebeard by “a fairy” (rather than the key being “fée,” or enchanted). The introduction of a love interest for Bluebeard’s wife makes the allusion to Othello tidy and ironic. Desdemona has lost the handkerchief through no fault of her own because it has been picked up and taken by Emilia, but while innocent she is forced to tell the lie that the handkerchief is not in fact lost; Fleurette has a key that has turned blue to betray her transgression, and she is deliberately withholding it, but here tells the truth: “It is not lost.” Whereas Othello’s fears that Desdemona is having an adulterous affair with Cassio are founded on nothing but the “trifles” that Iago turns into evidence against them, Fleurette (or Fatima) is actually in love with Joli Coeur (or Selim).

Planché’s “extravaganza” (burlesque, burletta) set the mold for the Blue Beard burlesques that follow it, of which there were many, but his style was considered more subtle than the burlesques that followed. There are barely any puns, and the ones that are used are subtle. O’Shac O’Back has been in the chamber dusting the heads and the bodies, presumably in order that Fleurette can realize the full effect once she opens the door; Abomelique’s countdown to Fleurette is deliberately exacting (five minutes, four, two and a half, two and a quarter …), and Anne (who has been looking with a telescope) berates her brothers for coming on horseback instead of “by the rail-road.” That is the extent of the exaggerated comedy of Planché’s style.

For the English comic tradition, the production that decidedly broke the mold set by Colman and Kelly, being a new import from a French opera bouffe, was: Bluebeard Re-Paired: A Worn-Out Subject Done-Up Anew. An Operatic Extravaganza in One Act, music by Jacques Offenbach, arranged by J. H Tully, the libretto by Henry Bellingham, adapted from the French of Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy.24 It was first staged in England at the Royal Olympic Theatre, Saturday June 2, 1866.25

At the point of Bluebeard’s entrance at the king’s court, the band strikes up Kelly’s March, but is stopped with these words from the king: “Hold! Michael Kelly must tonight the bâton yield, / for Offenbach to-night commands the field” (26). Fleurette in the French becomes Flora in the English, and Selim becomes “Saphir” in both French and English versions. In the comic opera, Bluebeard’s story is a parallel plot, not the only plot, and the affair of the lovers takes up a much greater portion of the drama by giving Fleurette a royal identity that has been kept hidden. The American edition published by Oliver Ditson and Co. gives both the French and a fairly close English translation of the French, with the Music of the Principal Airs (by Offenbach). The “Argument” provided gives the plot, with the names used in the original French. Boulotte, a “rustic maiden,” is chosen by lot to be the Rose Queen and Knight Bluebeard’s sixth wife. Fleurette, in fact Princess Hermia, long-lost daughter of King Bobeche, is discovered living in the village and returns to court. Prince Saphir, disguised as a peasant, follows her there. Bluebeard brings Boulotte to court with comic results. Spying Hermia, he determines that Boulotte should be poisoned so he can marry Hermia instead. Hermia is betrothed to Saphir, who is revealed to be the prince who had been disguised as a peasant. The alchemist who is to poison Boulotte does not kill her; she is revived in the company of the other wives. The prime minister reveals that he has likewise rescued several courtiers who had been doomed by the king. Bluebeard is denounced at court. His punishment is to keep Boulotte as his wife, while the other wives marry courtiers. Such is the French original on which the English version is based.

The English of Bellingham’s libretto (published in London by Lacy) has a few substantive changes to this French template: the king does not execute his courtiers out of jealousy that they are meeting the queen, but out of mere pettiness. In addition, French allusions such as the aspirations of the prime minister (“Shall I be a Richelieu? Shall I be an Oliver?”) are of course changed in Bellingham’s version. In fact, the prime minister is changed to a different agent of the king entirely: Robert, the English bobby (a common target in nineteenth-century comedies), the “hi of the law.” Robert is proud of his own deductive reasoning and speaks with stereotypical pompousness: “Them are secrets of state, Popolani, which, not knowing, it are not for me to divulge” (1866, 9). The second English stereotype incorporated by Bellingham is that of Jeames [sic], a courtier of the king and stereotypical English butler, punctuating his speech with many a “Haw!” The French original contains an ironic reference to the Bluebeard story that Bellingham for some reason removed: when the prime minister Oscar is to reveal that he has not in fact executed the king’s men as he was ordered to, he produces the key of their hiding place: the alchemist refers to the key of the Bluebeard story by asking if it is blood-stained (tachée de sang), and Oscar replies: “No, not that” (36). Given that the alchemist has purportedly been poisoning the wives, the blood-stained key of Perrault only makes its appearance through this allusion.

Bellingham’s anglicized version acknowledges the break that has occurred with English tradition as represented by Colman and Kelly. The first scene of the opera bouffe is pastoral; Flora the milk maid (later revealed to be the missing Princess Periwink) flirts with Saphir, the shepherd who is in fact a prince in disguise. Comic relief is in the form of Mopsa, a plain maid, in love with Saphir (her line: “My heart is pit-a-patting” [7] is an obvious allusion to Colman and Kelly’s duet between Selim and Fatima). Robert enters the village to search for the princess, sent down the river in a cradle as an infant, and now eighteen. Coincidentally at the same time, Popolani, an alchemist, enters on the opposite side of the stage, in order to obtain a Queen of the May for Bluebeard to marry as his sixth wife. Mopsa throws in her lot, and wins the lottery. The drawing takes place using a cradle, engraved with “E.R.” on the side; seeing this, Robert pantomimes “extravagant joy.” The E. R. stands for “Earlypurl Rex,” and Flora admits she is the child who came from that cradle. Flora now pledges herself to her “shepherd,” Saphir: “Now our hearts with joy replete / Both in unison shall beat.” Bluebeard arrives after they have left the stage to find his Queen of the May, Mopsa.

The second scene takes place at court, with a brief satire on the ways of court: “Who is prudent and discreet, / Let him study bowing, scraping; / Who would ruin be escaping, / Let him thus make both ends meet” (20). The king is proven as bad a tyrant in his way as Bluebeard: the king orders one of the courtiers to die because his obeisance falls short; this is the fifth man to be so condemned. Robert announces that Saphir will come courting that afternoon for the princess’ hand, and Lord Bluebeard will present his sixth wife immediately after. The king’s marriage to Queen Greymare is demonstrated to be a difficult one; they detest one another. The princess is averse to being married off to a prince, as she is in love with her shepherd; Prince Saphir arrives, and she realizes her error. Bluebeard arrives with Mopsa, who again provides comic relief by being unaware of the ways of the court. Bluebeard plans to murder Mopsa before Periwink can marry Saphir, so that he may marry the princess instead.

Scene 3 takes place in the Alchemist’s Chamber. Popolani has had a vision that Mopsa will be Bluebeard’s proverbial “last straw.” He is ordered by Bluebeard to poison her like the others. Bluebeard shows Mopsa the chamber and forces her to read the headstones of the five wives, reserving the last for her. Popolani does poison Mopsa, but revives her with electricity. In a grim twist, all the previous wives have also been so revived, but are now a form of harem for Popolani himself: “Now, what doth remain to me? / Why, only dear Popolani!” Mopsa rises to the occasion and rallies them with the hope of future husbands.

Scene 4 returns to Earlypurl’s castle for the conclusion. The marriage procession of Saphir and Periwink is interrupted by Bluebeard. When he is refused he threatens rebellion: “I’ve brought a handful of my guards, sire, / Twice fifteen hundred cannoniers; / One word, and like a house of cards, sire, / Your palace falls about your ears” (42). Bluebeard appears to win this round; he runs Saphir through with a sword and leads Periwink off. It remains to Robert and Popolani to scheme the outcome. Popolani knows the six wives live; Robert knows that the five courtiers condemned to die by the king are also still alive; they plan to revive Saphir to make the number even and arrive at the castle with the twelve dressed as gypsies. Back at the court, the gypsies arrive, and Mopsa reads the king’s palm, revealing that the queen will outlive him, and that he had condemned five men to death. Bluebeard’s six wives all unmask, and Saphir and Periwink are also reunited (although she has already been married to Bluebeard). The solution is to marry the courtiers to the wives of Bluebeard; Saphir and Periwink are a couple, as are Bluebeard and Mopsa. In their plea to the audience for applause, Bluebeard makes a traditional observation that he might be better understood by the men in the audience: “With the men p’raps I may go down, / But ladies at such freaks will frown” (49).

After 1866, Offenbach’s opera bouffe was popular on stages on both sides of the Atlantic.26 The music was noted as independently available from book and music sellers. There was also a spinoff in the form of Boulotte, which seems to be a title only used in America at this time.27

Bluebeard was frequently performed at home, by adults and children in one-act drawing room dramas and even in charades. Charlotte Cushman, later a renowned cross-dressed Romeo of the Victorian stage, reputedly played the role of Selim (which became a female role during this period) at home in her mother’s attic as a child.28 At the other end of the century, younger sister of the future American president Roosevelt, Corinne Roosevelt, played the part of Alphonso (one of the two sons of Lady Grasping) in a parlor play called Blue Beard. While she was prompted by a typed script,29 the play was a published one: Blue Beard by Sarah Annie Frost. Frequently, such plays came with stage business helpfully added for the amateur and juvenile actors at home.

By 1841, as seen in Francis Gower, Earl of Ellesmere’s Bluebeard; or, Dangerous Curiosity and Justifiable Homicide, Bluebeard has reverted to the popular “Pacha of three Tails.” The cast of characters includes Fatima, Anne, Schacabac (now their father, who like Colman’s character Ibrahim, rhymes “father-in-law” with “three tailed bashaw”),30 and as in the 1839 burlesque of Planché and Dance, the tone is obviously comedic. “Miss Fatty” is told that the fault of all of the previous Mrs. Aboumeliques [sic] is that they were “too fond of hurlothrombo pudding.” Immediately she wants to know: “How is it made? What does it look like?” (24). Again the play alludes to Othello through the implicit reference to Othello’s mother on her deathbed: “Bluebeard: My mother was a witch, and on her death-bed told me truly, / That womankind are all alike, rebellious and unruly, / And can’t be trusted any more, her own expression was it, / Than in an hen-roost can a fox, or a cat in a china closet” (27). In the same exchange, the pudding itself is said to be enchanted: “Know, abandoned woman, the hurlothrombo pudding was a fairy. Therefore, as a non-sequitur, down on your knees and prepare for death” (27). A mock preface, dated in the future French Republic of 1870, accords the play the status of a found document, ascribed to John Milton. Reading through the humorous barbs directed at Shakespeare and via the French at the English, it seems as if the author’s family acted the play privately, for Christmas. Gower’s comments here about Milton’s female characters (and precursors for Bluebeard’s wife) are interestingly allusive themselves: “Nothing can be more consistent with his known tenets than the character which he gives the female sex through the mouth of Bluebeard, as elicited by the reprehensible conduct of the heroine Fatima. … The whole passage is worthy of the man, who, rising above the prejudices of his age and country, turned his wife out of doors, and advocated the doctrine of unlimited divorce. Fatima differs, indeed, from the Lady in Comus; but she bears a close resemblance, both in character and incident, to the Eve of his five-pound poem, and to Dalilah, the heroine of a piece which appears to have been written by Milton for one of the minor theatres of his day” (11). The epilogue, spoken in the persona of Captain Napier, counsels men to leave marrying at seven wives, rather than to add an eighth; women are to control their appetites, and by referencing the cover to the pudding makes an implicit connection between greed and sexual appetite: “And you, ye fair ones, who beheld with dread, / How nearly Fatima had lost her head, / Remembering that an appetite in you / At seven is vulgar, learn to lunch at two. / And dining with your husband or your lover, / Wait till he lifts, or bids you lift, the cover” (n.p.).

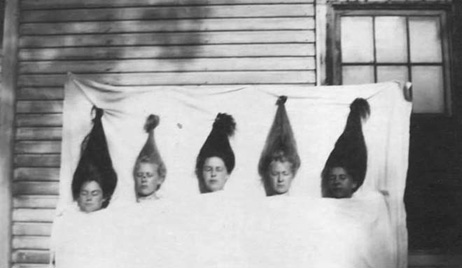

Parlor plays of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries gave information on how to make the “bloody chamber” scene. This photograph shows the results. Courtesy of Evan Finch.

Much can be gleaned from this advice as to how these home productions were conducted. The play Blue Beard, or Female Curiosity, A Sensation Drama in Two Acts and Two Scenes, By an Experienced Amateur (Dean & Son 1871) is very short, and evidently aimed at young or very amateur performers in its easy, memorable rhyme (“It is no jest: look at those spots; / What say you to those crimson dots?” [7]) and easy actions (“FATIMA clasps her hands in an attitude of abject terror. BLUE BEARD folds his arms, and glares at her” [10–11]). The play text includes extensive information to assist with the production: a sample play-bill with the suggestion to print and circulate it, and costume ideas: Bluebeard’s beard “can be made of blue fringes” (3). Selim can be “dressed either as a civilian, or as a common Turkish soldier” while the citizens can be dressed in “Every variety of Eastern costume that can be improvised” and their number can be reduced “if the effect is not so much the object as acting” (3). Finally, production advice includes the following: “A piece like BLUE BEARD can be made most effective by the expenditure at the fancy stationers’ of a trifling sum in the purchase of gold-paper, gold-paper ornaments, tin-foil, and pasteboard” (3). Throughout, the script is interspersed with stage directions that often indicate what the action is supposed to mean: “She is supposed to impart the mystery of the Blue Room to SISTER ANNE, who seems petrified with horror and surprise, not unmingled with incredulity” (7). There is a reference to Anne Boleyn at the end of Act I, and to Mary, Queen of Scots, so that in the second instance Anne corrects Fatima: “Stop, dear, you make a trifling error; / Of course you’re flurried in your terror. / A queen, and not a king, ’tis said, / Sent to the block poor Mary’s head” (8). Act II begins with Kelly’s “Blue Beard’s March,” “if it can be managed” (8). Sister Anne is able to do her lookout lines from a window, if there is one, changing the word “turret” to “window” to suit, or beside the stage, if not. There is helpful props advice given to accompany the final sword battle: “As they fight they should use the black iron swords sold at the toy shops, and, to make the combat effective, it would be well to practise so as to make the blades strike fire. This can be soon learnt” (13).

Finally, the script for a “Blue Beard” charade by Miss E. H. Keating in Dramas for the Drawing Room; or Charades for Christmas is similarly helpful in providing an insight into Bluebeard’s use as parlor entertainments. Scenes are given for each syllable, and then for the whole word (blue beard). The scene for the first syllable (blue) is relatively lengthy, full of references to color (including two characters, Mr. Indigo and his wife Lady Violet), and many red herrings (volumes of references to current technologies and scientific lectures). But the clues are of course present: repeated references to “blue,” lots of French expressions and discussion about the use of French in the house; the explosion in the kitchen of a device that perhaps recalls the pantomime scene where Bluebeard does the same; a reference to Othello, and Lady Violet having “no desire to become a domestic Desdemona” (9); a handkerchief (9); a reference to “tails from the Tartars” (10), and to human hair; and finally, where the syllable should be supplied at the end of the scene, the orchestral music “My Own Blue Bell” (12). The second scene is much less oblique; two men meet after they have both grown beards. They comment frequently on them. The final reference is “in case the Russians should invade old England, why we should be able to beard them” (17).

The final scene is longer, performed in “intensely Turkish [costumes] of the old school” (29), and contains a complete rendition of the Bluebeard story, using Colman and Kelly’s template, without the Shacabac/Beda subplot (and keeping the name Irene for Fatima’s sister), with Selim on a banjo, using music from the 1798 production in several instances. As seen in the same author’s home play of the same tale, the ghost of one wife speaks to Fatima, warning her to escape, and the ghosts defer to one another trying to get back into order again. Also seen in Keating’s play, the Bashaw has three pages, each holding up one of three tails; when the brothers kill him, they do so by severing these tails, at which point he lies down (and gets up again). There are topical references such as to a caricature (of historical novelist G. P. R. James) in Punch by Thackeray, “Barbazure.” As had by then become a common motif, Abomolique [sic] plans to take a train and returns because he mistook it. In Scene 2, Irene coaxes Fatima to open the door “He meant you to go in, or else would he / Be such a goose as to give you the key?” (24). They send a page off for scouring drops to clean the key with, but Abomolique returns early, quoting Othello: “That key did an Egyptian with my mother barter / For two old hats, and Fox’s Book of Martyrs” (26). He tells her to prepare herself “As tragic heroines do, by letting down your hair” (27) and gives her time to get some bill and wage-paying done. Not that it would be possible for an audience still to be in the dark this point, Selim mentions “he … in nursery story” (29) and finally states that Abomolique has gone “Down where the Blue Beards go” (29).

The popularity of “Bluebeard” as stage entertainment is not very surprising, given its inherently dramatic nature. It success in comic form is perhaps more surprising, but once the melodramatic mold of Colman and Kelly’s production had been burlesqued, both in pantomime and extravaganza, it developed rapidly and inventively, until finally even the repetitions of comic motifs became clichéd. The persistent models for the fairy tale were those of Perrault, as adapted by Colman and Kelly and as burlesqued in a variety of comic forms. Despite the arrival of the Grimm’s variants of this fairy tale in English in the midnineteenth century, the impact of these later arrivals was not registered in dramatic form. Through this popular currency Bluebeard assuredly would have been recognizable in nineteenth-century arts and letters drawing on the story to however wide an audience they aimed to reach.