CONTEMPORARY BLUEBEARD

Bluebeard proliferated throughout the latter half of the twentieth century. As the protagonist of Loren Keller’s novel Four and Twenty Bluebeards writes, “there was plenty of room in the ‘postmodern’ world, or any other, for my twenty-four versions” (1999, 257). In the contemporary landscape, these versions are simultaneous with one another. Charles Ludlam’s avant-garde play Bluebeard (1987) features a Bluebeard who is part mad-scientist, part “Turk” (2.9), and it is set in part to Béla Bartók’s music from the opera Duke Bluebeard’s Castle. As Charles Dickens predicted, the “counterfeits” have taken the field.

“Bluebeard” works in the latter half of the twentieth century make full use of the tale’s self-reflexivity, enhancing it through postmodern techniques.1 As in the case of Keller’s protagonist, who spends a “Bluebeard summer” acting the role of Bluebeard in George Bernard Shaw’s play St. Joan and whose personal life becomes embroiled by living with a dyed beard for the duration of the run, the tale’s characters become self-aware. The earlier one-act comedy Bluebeard Had a Wife (1957) resembles every other Victorian amateur production in every way, including slapstick (with a dead fish). However, in addition to a forbidden “cabinet,” the tyrant Bluebeard also keeps a forbidden book, his memoirs: “BLUEBEARD (smiles contentedly as he reads aloud): ‘There was a man who had fine houses, both in town and country, a deal of silver and gold plate, embroidered furniture, and coaches gilded all over. This man was so unusual as to have a blue beard— (He strokes his beard admiringly.)—which made all the townsfolk run away from him.’ (He chuckles at the thought)” (Kelly 1957, 11).2 The climactic revelation is in fact accomplished first with Anne suspensefully reading aloud from the book: The wife recognizes that “those are the very words he spoke to me” (18). When Anne reads aloud the discovery of the bloody chamber, the cook faints. Even in juvenile literature, postmodern self-reflexivity is the norm. In the illustrated children’s book The Three Naughty Sisters Meet Bluebeard (Capdevila 1986), the sisters are sent back into story land by the Witch, help the wife open the forbidden door (discovering Bluebeard behind it), decide to trick Bluebeard, and save his wife. Under threat of crocodiles, they realize they can alter the story they are in and take an eraser to the crocodiles, thus defeating both Bluebeard and the Witch.

In addition to making the story the subject, these referential texts play cat-and-mouse games with the reader, foregrounding the reader’s own complicity and processes in reading intertextually. The story is not only about Bluebeard; the story is Bluebeard. The text is Bluebeard’s castle, while the act of reading is thereby allied with the wife’s simultaneous acts of investigating and transgressing. Such is the case, for instance, with Donald Barthelme’s story “Bluebeard” (1987), which continually thwarts the reader’s intertextual presuppositions, and with Max Frisch’s novel Bluebeard: A Tale (1982).3 The pattern is characterized in “Bluebeard’s Second Wife” by Susan Fromberg Schaeffer, in which the reader is first reassured: “you know all about the castle” (1988, 571) and then told there is a secret chamber nonetheless: “Of course, you think you know what happened next” (573). Méira Cook’s story “Instructions for Navigating the Labyrinth” (1993) also sustains the conceit: it is fragmented and combines different genres within the story: riddles, direct address to the reader, and a Bluebeard story, all of which are interconnected through the reader. The story here is malevolent: a labyrinth that is impossible to escape: “How do you enter the labyrinth? / Reader, turn left turn left turn left” (107). Again, as in “Bluebeard’s Second Wife,” it encourages the reader to make equations with the Bluebeard story specifically in order to thwart them: “You know the rest” (108). At the same time, the text is informing the reader throughout that it is doing so: “This is the story of a red-herring so that you will recognize one the next time it swims past” (111).

This chapter charts the contemporary forms “Bluebeard” has adopted in the (now much broader) Anglophone tradition. As has been seen, self-reflexivity often takes the form of Bluebeard as an artist, writer, photographer, or art collector. By actualizing these self-reflexive gestures, postmodern texts explore various crises of artistic representation, most often around the display of murdered female bodies and the act of looking, as seen in Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Bluebeard (1987). The contemporary tendency to self-reflexivity has been put to extremely productive use in feminist works using the Bluebeard story to challenge cultural assumptions about gender, violence, and artistic representation. The tradition of self-reflexivity inherent in depicting Bluebeard on film is also used to challenge traditional genre representations and constructions of the gaze, as seen in The Silence of the Lambs (1991) and The Piano (1993) to be discussed at greater length. Finally, the contemporary women writers Margaret Atwood and Angela Carter both return repeatedly to the Bluebeard story in their various works, as did Thackeray and Dickens in the nineteenth century. They also rewrite the tale, reflecting a feminist focus. Underscoring this, there has been a notable shift in the direction of Grimm variants and “Mr. Fox” with their tropes of dismemberment and cannibalism, but also female trickery and self- and “sister”-rescue.4

Of course, more than simply a collector of women, Bluebeard has always been an “artist.” While his grand house features gilded mirrors rather than paintings, foreshadowing the nature of his artistry, Charles Perrault’s Bluebeard crafted the tableau of dead wives in the “forbidden” chamber presupposing a specific spectator: his transgressing wife.5 He has deliberately crafted a tableau mort to reflect the living wife who will soon become part of the image she has seen, claimed by this uncanny mirror. He tells the wife: “as you have seen, so shall you be,” transforming female spectator into “spectacle.” The tale is thus predisposed to self-reflexivity and the use of mirrors and doubling, as well as the double and self-contradicting moralités, indicate that Perrault himself actualized this metadiscursive potential. Considering murder as death artistry is a common metaphor. Contemporary depictions of serial killers as death artists6 owe a debt to writers such as Thomas de Quincey’s “On Murder as Fine Art” and to the Marquis de Sade (whose novel Justine [1778] alludes to Bluebeard by name), as much as to the procedural relationship whereby the killer shapes the corpse tableau for the detective to analyze.

It is a short step from there to make Bluebeard an actual artist of some kind in addition to his tableau creation, further enhancing the tale’s self-reflexive possibilities. The Victorians were familiar with referring to Bluebeard as a collector. As the song “Oh! Mr. Bluebeard” put it: “Now some collectors hunt for gems, / Others for guns and knives, / Pictures or lamps or slippers or stamps, / But he collected wives” (Chapin [1910], n.p.). In the English variant “Bloudie Jacke” (1842), recorded by the Victorians, the Shropshire Bluebeard is a cultured figure whose ladyfingers figure among Rembrandts and other rare pieces of art. The woman’s intrusion seems uncultured:

She roams o’er your Tower by herself;

She runs through, very soon,

Each boudoir and saloon,

And examines each closet and shelf, Your pelf,

All your plate, and your china—and delf.

She looks at your Arras so fine, Bloudie Jacke!

So rich, all description it mocks;

And she now and then pauses

To gaze at the vases,

Your pictures, and or-molu clocks;

Every box,

Every cupboard, and drawer she unlocks (203).

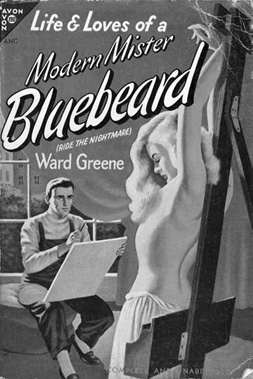

In the twentieth century in particular, Bluebeard emerges not just as an art collector but as an artist in his own right. The 1949 Avon cover of Ward Greene’s novel Lives and Loves of a Modern Mister Bluebeard (1930) depicts an artist drawing a woman who is naked from the waist up, herself tied to an easel, mirroring a scene in the novel in which the model finally faints, unnoticed by the artist. In the 1947 film The Two Mrs. Carrolls, one of the 1940s “Bluebeard cycle” of films,7 Humphrey Bogart plays an insane Bluebeard figure who paints his best work when he has decided to kill the woman who is its muse. The painting “The Angel of Death” representing his first wife hangs ominously over the mantle in the home he shares with his second wife. He tells the second Mrs. Carroll, once he has completed his skeletal painting of her and has resolved to kill her in favor of another: “You made my work live again. Now there’s nothing more from you. So I must find someone new.” In Edgar Ulmer’s film Bluebeard (1944), Bluebeard is a painter and puppet maker, and one of his paintings is taken into court to be analyzed: to discover its artist is to discover the murderer.

Three later twentieth-century works in particular demonstrate the critical exploration of representational practices at work when Bluebeard is a visual artist. Edward Dmytryk’s film Bluebeard (1972) thematizes photography and plays cinematically with the viewing audience. Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Bluebeard (1987) deconstructs both realism and abstract expressionism, attempting to arrive at a postmodern theory of art that can express humanism. Cindy Sherman’s photographs in Fitcher’s Bird (1992) invite spectators to be self aware in their role in relation to the photography that is viewed.

Edward Dmytryk’s film Bluebeard depicts Baron Kurt von Sepper (Richard Burton) as an artist whose images derive from photography. He photographs women’s faces when they are dead and traces them into unrecognizable intricate line drawings. The face is so embedded that the image is on public display in his mansion. The serial murder of his wives is represented in the film by increasing the number of pictures on the wall in a series of brief, juxtaposed shots. The women incorporated in them are not shown until much later in the film, as flashbacks. In some scenes the baron or his housekeeper is able to watch the new wife looking quizzically at the image: a face looks at a face through a face; the last wife Anne comes face to face with her likeness even before she opens the forbidden chamber.

Avon cover (1949) for Ward Greene’s Life and Loves of a Modern Mister Bluebeard (1930). Bluebeard has often been identified with an artist, creating a tableau of women for other women to see. Copyright © 1930 by Ward Greene. Avon reprint edition copyright © 1948 by Avon Publishing Co., Inc. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Through the perspective of the last wife Anne, the secret chamber is finally depicted. The entrance is through a life-sized hunting portrait of the baron and this reveals a room that is a freezer. The baron’s wives are literally frozen within this room. The act of opening the door triggers a hidden camera to photograph the evidence of transgression; first the frozen image is formed, then the women are frozen into these images. The baron takes Anne into the darkroom to show her the photograph of herself that he has developed, inviting her to see herself as he sees her. Again the film’s representation of this image is redoubled, by virtue of Anne’s previous discovery of a room filled with headless dressmaker’s mannequins from whom these frozen women are at first indistinguishable.

The film is self-aware and even parodic to an extent. The casting and frequent nudity of the international female stars was contrived to fulfill foreign distribution requirements. The murder of the first wife for her incessant singing (“How else could I shut her up?”) is followed by other overdetermined motivations. Raquel Welch plays a chaste nun who, once she has agreed to marry the Baron von Sepper, disburdens herself of an endless confession of male lovers accompanied by an increasing state of lurid undress, driving von Sepper to shut her up in a coffin. Yet the brash Anne, played by Joey Heatherton, who attends his funeral with the gold key prominently around her neck, is unable to rescue herself (she requires help) despite buying time for rescue by trying to get her husband to talk himself into a cure. In a psychoanalytic echo of Scheherezade’s role, she will be killed at dawn but she prompts him to heal himself by telling her everything in flashback of his previous wives. By analyzing his pattern, she diagnoses him contemptuously. He is unaware of his own impotence and the fact that he kills his wives at the point when they demand a sexual relationship.

The choice of photographer-artist for von Sepper is interesting given his choice of forbidden chamber, which is the freezer. The frozen image is represented multiple times in the film. These are the forms of the baron’s death artistry, effectively set in contrast with the moving image that is embedding all these representations. The film outlives the baron; just as Anne was shown from behind, photographed in the moment of transgressing, she is again shown from behind as she walks away from the baron lying dead (and posed) at his funeral.

Yet for all its domestic focus, the film attempts to depict a broader ramification of von Sepper’s cruelty and impotence. It is implied that his impotence derives from his wartime experience. He is depicted as a returning war hero at the outset of the film and his blue beard is the result of being shot down and burned. Called to one of his honeymoon beds, he faints and is put to bed by the doctor instead, who insists on the rest that all war heroes deserve. His impotence and its wartime cause are inextricable. Further, the way he speaks about women as monsters who “only began to look human when they were dead” objectifies them in ways linked with his anti-Semitic politics. Thus, although he is incapable of seeing the connection, von Sepper’s Nazism and his order to raze a Jewish quarter sow the seeds of his downfall by the hand of a man whose parents were killed. The depiction of the holocaust does more than extend von Sepper’s characterization. True to the trope, the last wife survives Bluebeard’s attempts to freeze her in (his) frame; by spilling out from the embedded flashbacks into the present, in which the baron is killed and Anne is saved, the film both depicts images of holocaust and yet does not contain them. The survivors (Anne and the unnamed Jewish man) are allied with the moving image itself.

Depicting Bluebeard as a photographer in a film gives rise to self-reflexive commentary on the art of representation. Using an abstract expressionist painter, Rabo Karabekian, as the main character for his novel Bluebeard (1987), Kurt Vonnegut provided a metaphor for his own artistic engagement. Karabekian’s house guest, Circe Berman, tells him his art is solipsistic: “What’s the point of being alive … if you’re not going to communicate?” (35, original emphasis). This criticism prompts Karabekian to open up his secret museum in the potato barn. Here, he has locked away a large painting depicting the “unutterable” sight as he saw it on D-Day, May 8, 1945. The painting is called “Renaissance” and it unites representational realism with his previous abstract expressionist works.

The novel comprises a debate between the ancients and the moderns as well, in the form of mimetic realism on the one hand and abstract expressionism (and modern art in general) on the other. Karabekian, a child of Armenian refugees, a seventy-one-year-old painter and art collector, began his artistic career apprenticed to a fascist “Bluebeard,” Dan Gregory. Gregory’s thinly disguised fascist sympathies are made analogous to his photorealistic art. Gregory’s art uses realism as a weapon and repels the spectator. He is an admirer and advocate of Mussolini who would, he says, “burn down the Museum of Modern Art and outlaw the word democracy” (132). Rabo Karabekian’s father says of a camera: “all it caught was dead skin and toenails and hair which people long gone had left behind” (76). By making his art camera-like, Gregory is likewise a brilliant “taxidermist” (82). He is further linked with Bluebeard in that his house has a Gorgon-head knocker on the front door and eight human skulls on one of the mantles. The photographs of his wife, Marilee, in which she is posed and costumed in different ways renders her unrecognizable to Karabekian, who sees her in Gregory’s paintings as “nine different women” (77).

If Dan Gregory is Bluebeard, Karabekian is his apt apprentice. He tells his house guest Circe Berman: “‘I am Bluebeard, and my studio is my forbidden chamber, as far as you’re concerned’” (46, original emphasis). Now writing his autobiography in his Long Island gallery/mansion, under Berman’s tutelage, he is undergoing his second resurrection. Karabekian’s description of his career illustrates a layered process through at least three discernible and distinct phases, each expressed by an artistic work on the exact same canvas at three different times. After mimetic realism, the second represents abstract expressionism. The third, entitled “Renaissance,” is a new communicative act for Karabekian, despite its being locked in the potato barn that Circe is forbidden to enter.

Karabekian’s own talent as a “camera” (44) who can “capture the likeness of anything [he could] see” (43, 236) remains his hidden “reserve” when he turns to the new school of abstract expressionism, which prevents these works from being the form of expression he is hoping for. In the orange field titled “Hungarian Rhapsody,” Karabekian first sketches a caricature of his friend intended to display his talents, but this face remains and reemerges after the demise of the painting, when the paint flakes off the canvas. In attempting to escape history by painting over it, he has only achieved a camouflage. Even the seven strips of tape on this orange canvas are not the “pure abstraction” (256) that they masquerade as. To Karabekian they “secretly” represent six deer in a glade and the lone hunter who has them in his sights (256). Like Gregory’s art, which is antagonistic to the viewer because of the absoluteness of the mimetic vision, these abstract expressionist works are “meant to be uncommunicative” (35, original emphasis). The works produce responses like the following, from Karabekian’s cook: “They just don’t mean anything to me … I’m sure that’s because I’m uneducated. Maybe if I went to college, I would finally realize how wonderful they are” (127).

The third painting is a “Renaissance” (265) in that it involves a turning away from the self-sufficient forms of either photographic realism or abstract expressionism and is instead an attempt to communicate. It depicts representative humanity in 5219 figures in a D-Day vision of survivorhood. David Rampton contrasted this with Bluebeard’s art in his comments on Vonnegut’s novel: “In Bluebeard’s secret chamber is death; in Rabo’s, a painting that depicts life and death, the survivors of a six-year nightmare of bloodletting caused by people who make Bluebeard look like Mr. Rogers” (1993, 22). There is a story for every figure, but after the barn is opened to the public, as the painting already in a sense has been, the painting becomes “activated.” This signals Karabekian’s return to a world of community and communication after his seclusion. The painting’s name also signals return: “Now It’s the Women’s Turn.” Lawrence Broer interpreted this in the context of the Bluebeard story: “By contrast to the obscenely destructive male of the seventeenth-century tale by Charles Perrault, Rabo notes that it is the female of the species who plants the seeds of something beautiful and edible” (1989, 168). Like Karabekian, Broer was quoting Marilee’s comparison of men planting mines and women planting seed. Earlier, Gregory’s wife Marilee summed up abstract expressionism as a male artistry about “The End.” In turning back from the end, this work is a turning back on the threshold of Bluebeard’s chamber. Karabekian’s “forgiveness” is opening his work to the viewer: “‘Make up your own stories as you look at the watchamacallit’” (270).

The book of Cindy Sherman photographs Fitcher’s Bird is self-reflexive, like all of her photography, in which she tends to serve as both photographer and subject. But like the fictive painter Karabekian, she actively separates her pieces from overdetermination by the artist in order to open them up to reader’s narrative engagement with them.8 She does not title the majority of her photographs; even one of the History Portraits depicting her posing as Judith of Holofernes is untitled (#228). Sherman’s gestures are highly postmodern: rejection of genre stratifications, use of borrowing and pastiche, and use of photographic medium to create nonphotographic art (confounding “high” art culture of painting with traditionally “low” genre photography). At the same time, what Sherman represents throughout her work is the female body. Sherman’s artistry enlists the viewer to acknowledge objectification of the image by oscillating back and forth over the surface/depth schism.9 Sherman’s photographs are not static but filmic and narrative. She repeatedly stresses the narrative engagement the photographs encourage of the spectators. The role of the camera (and thus the location and directing of the spectator’s gaze) in her work is immediately self-reflexive in a way that a novelistic description of a painting is not and works to deconstruct the camera’s construction of gaze. Her work then functions less as model of static visual art than as a useful feminist deconstruction of what is at work in mainstream filmic representations of women’s bodies.

Fitcher’s Bird is representative of her work on the female body in that it uses dolls, masks, and medical prosthetics, Sherman’s favorite props when she is not herself deliberately masquerading as the model. The photographs of the Fitcher’s Bird series feature high-key lighting and vivid color saturation. The grotesque is juxtaposed throughout with the pathetic, whether it is in the form of the grubby fingers and dirty feet next to pristine hands and shiny eggs, or the contrast between viewing Fitcher seen from an extremely low angle as a predator or the second time from above, reflecting the power shift as he struggles to carry the basket hiding one of the sisters inside back to their parents’ house. In all cases the frame is filled with close-ups and extreme close-ups: there is no comfortable distance from which to assume the role of a passive spectator. The artistically decorated skull with jewels is suspiciously clean and fresh looking next to the dirty, hairy, and sweaty figures who are “alive”; the irony is that Sherman’s pristine “art” is prepared to get dirty. The choice of “Fitcher’s Bird” also highlights a shift in focus to female artistry and its role as a strategy for self-rescue, and both the feathered bird and the decorated skull are appropriately two of Sherman’s set pieces.

In 1961, Sara Henderson Hay’s poem “Syndicated Column” targeted traditional gender platitudes through ironic use of a traditional genre and using an even more traditional poetic form, the sonnet:

Dear Worried: Your husband’s actions aren’t unique,

His jealousy’s a typical defence.

He feels inadequate; in consequence,

He broods. (My column, by the way, last week

Covered the subject fully.) I suggest

You reassure him; work a little harder

To build his ego, stimulate his ardor.

Lose a few pounds, and try to look your best.

As for his growing a beard, and dyeing it blue,

Merely a bid for attention; nothing wrong with him.

Stop pestering him about that closet, too.

If he wants to keep it locked, why, go along with him.

Just be the girl he married; don’t nag, don’t pout.

Cheer up. And let me know how things work out.

While feminist treatment of the Bluebeard tale is arguably embedded within the variants themselves, with “trickster” women figures like Scheherezade and all the women who rescue themselves through wit, courage, and trickery, it was an increasingly insistent phenomenon through the course of the twentieth century to take the fairy tale and retell it, further privileging the woman’s own agency and empowering her within a format that has, like Hay’s “Syndicated Column” writer, enculturated girls into subservience, silence, and passivity. Traditional and misogynist forms do persist. Alongside Bluebeards for mature readers in the three-part Bluebeard comic series by James Robinson (1993) and illustrated by Phil Elliott10 is the Mills and Boon/Harlequin romance version of the tale: Bluebeard’s Bride (Holland 1985).11 These are the two sides of the same cultural coin, as Fay Weldon wittily indicated: “The transformation from ugly duckling to swan fills the prepubertal child with unreasonable hope. After the wintry ice of rejection, the warmth of sun and acceptance will surely come. Well, perhaps, and hi there, Mr. Fox” (1998, 330).

Like Hays’ poem, in the short stories by Shirley Jackson, “The Honeymoon of Mrs. Smith” (in two versions) thought to have been written in the 1960s, the reader is invited through tragic irony to share the intertextual secret. The two stories are most interesting for being two complete versions of the story by the same author, neither of which was previously published. In each, Mrs. Smith has married a man, strongly suspected of drowning six previous wives in the bathtub and burying them in the cellar, on very little acquaintance. All the townsfolk are aware of her precarious position. In each version, however, the treatment is radically different. In “Version I” the townsfolk gossip about her but seem paralyzed and unable to talk to her about their suspicions, except for her downstairs neighbour whose concerns the wife dismisses as macabre fancy. The reader becomes aware of the wife’s predicament, but—as is the case with tragic irony—she never does. In “Version II: The Mystery of the Murdered Bride,” however, the townsfolk are unable to warn the wife of her predicament because she is perfectly well aware of it, having recognized the man from the moment he sat down beside her. But in this case, the irony is that foreknowledge has contributed nothing. She is fatalistic, complicit, seeing her election as inevitable destiny. Despite “seeing then the repeated design which made the complete pattern” this wife maintains “tactful respect for her husband’s methods” (83) and awareness of the role she is expected to play in the tragedy: “Everyone is waiting; it will spoil everything if it is not soon” (87). At the end of the story it is Helen prompting her nearly reluctant husband: “‘Well?’ ‘I suppose so,’ Mr. Smith said, and got up wearily from the couch” (88).

With metafictional techniques, the reader is invited more directly into the intertextual situation. In “Bluebeard’s Second Wife,” the reader is told: “Reader, if you find that castle, if you hear the voice of many women laughing, do not go in” (Schaeffer 1988, 578). In A. S. Byatt’s “The “Story of the Eldest Princess,” the narrator states just as baldly: “Keep away from the Woodcutter, if you value your life” (1992, 22). But the advice to avoid Bluebeards is ignored by the protagonists who are, like Mrs. Smith, increasingly self-aware but also empowered to alter the pattern instead of submitting to it. As in Byatt’s story, the postmodern self-awareness of Bluebeard’s survivors extends to awareness of the story they are in. Just as the princess says, “I am in a pattern I know” (16), the Bluebeard women know the pattern they are “caught” in. In Dora Knez’s Five Forbidden Things (2000) another “Bluebeard’s wife” states: “Well, she thought, there is always one thing forbidden to women” (26). In Annie Proulx’s short fiction “55 Miles to the Gas Pump” (1999), Mrs. Croom climbs to the roof to saw a hole in the attic to find what she knew to be there: “just as she thought: the corpses of Mr. Croom’s paramours” (491). The wife in Joyce Carol Oates’ “Blue-bearded Lover” only asks why she cannot go in to the chamber because she knows this to be her role in the drama: “for I saw that he expected it of me” (1988, 183).

Most tellingly, women are themselves dangerous in their cunning. In “The Wife Killer,” Lydia Millet wrote: “In the postmodern world Mrs. Blue Beard doesn’t take the bait” (1998, 230). This strategy is not always successful, as shown in another story where the heroine refrains from taking the bait to no avail. She tells her husband: “‘I think you’re entitled to a room of your own.’” However, her refusal to play the role still results in her death: “This so incensed him that he killed her on the spot” (Namjoshi 1981, 64). More often, though, being aware of the story and its assigned roles enables women to be tricksters themselves. In the poem “Visiting,” Jay Macpherson wrote: “Takes one to know one: he / Never fooled me” (1981, 92). This stance is reminiscent of all the “youngest sisters,” who always know how to deal with a murderer. These women have the knowledge of Bluebeard already, and by having “forbidden knowledge” these women are themselves dangerous. Sylvia Plath’s untitled poem from her juvenilia declares: “I am sending back the key / that let me into bluebeard’s study” (pre-1956, 305). The speaker has already been into Bluebeard’s study, after all, and so has knowledge of it. By referring to the forbidden space as a study, knowledge becomes at once literary and thus metafictive. In this context, “sending back the key” suggests the act of writing, and the act of writing about Bluebeard becomes the very means of outwitting his plot. As another narrator writes: “I will rewrite the story of Bluebeard. The girl’s brothers don’t come to save her on horses, baring swords, full of power at exactly the right moment. There are no brothers. There is no sister to call out a warning. There is only a slightly feral one-hundred pound girl with choppy black hair, kohl-smeared eyes, torn jeans, and a pair of boots with steel toes. This girl has a little knife to slash with, a little pocket knife, and she can run” (Block 2000, 165).

In some cases, “it takes one to know one” becomes more literal, as women are depicted as “Bluebeard in drag”12 themselves, with their own murderous secrets. In Celia Fremlin’s story “Bluebeard’s Key” (1985), the wife has a secret of a domestic murder she keeps from her husband, burying the evidence, a door key, in their back yard. In Neil Gaiman’s story “The White Road” (1996), while “Mr. Fox” is being beaten to death at the end of the story he sees the woman who has told the story that has caused his downfall, and she has a brush tail between her legs.

As this last reference illustrates, it is notable if not surprising that references to “Mr. Fox” become more prevalent in feminist revisions, as well as the use of the Grimm variants “The Robber Bridegroom” and “Fitcher’s Bird.” As has been seen, Cindy Sherman also uses the “Fitcher’s Bird” variant from Grimm rather than Perrault’s version. The 2003 collection The Poets Grimm reprinted both Allen Tate’s and Margaret Atwood’s poems entitled “The Robber Bridegroom,” and in both cases the severed finger is essential: “He will cut off your finger / And the blood will linger” (Tate 2003, 52); “He would like to kill them gently, / finger by finger and with great tenderness” (Atwood 1984b, 304). These variants are both more gruesome in their images of dismemberment and cannibalism, but also feature a heroine who rescues her murdered sisters and who is not herself rescued by outside agency but by her own wits. Usually, her escape relies on trickery and forms of storytelling, and even by using Bluebeard’s own artistry against him. Fitcher’s “bird” disguises herself; many of these heroines make effigies of themselves to trick Bluebeard into believing she is still there (unable to distinguish between a live wife and a dead one). In most, she tells the story disguised as a story to enact justice, an elaborate and gleeful feature that prolongs the revenge Bluebeard must suffer. The numerous feminist revisions of the Bluebeard tale all make thorough use of the tale’s inherent self-reflexive qualities and of postmodern techniques to enhance them.

As seen from the early cinematic representation of “Bluebeard” by Georges Méliès in 1901, film’s ability to engage the spectator becomes particularly metacinematic when the Bluebeard story is in play. In feminist terms, this inherent potential becomes the means of commenting on construction and ownership of the cinematic gaze, as we see with two contemporary “Bluebeard” films, The Silence of the Lambs (1991) and The Piano (1993).

The Bluebeard story has obvious thematic connections with standard tropes of horror, thriller, and serial-killer film.13 Marina Warner said, “The Bluebeard story can be seen as one of the slasher film’s progenitors” (1994, 270). Although the Bluebeard cycle of films has had no exact equivalent since the 1940s, the contemporary popularity and controversies of the serial-killer genre draw on the Bluebeard model explicitly. Jonathan Demme’s film adaptation both represents the broad transformation of the “Bluebeard” film into contemporary serial-killer films: seriality is central; women are collected and killed. Although the film’s relationship to several traditional genres is at issue, the arguments revolve around gaze, the spectacle of the woman who looks and is traditionally punished for it: “One thinks of the many instances in films where the woman, having heard a noise, looks down in the basement, or ‘behind that door’, and is promptly murdered, seemingly for daring to do so” (Dubois 2001, 300). At the same time, Demme’s film is controversial in its self-reflexive challenge to the genre through the reappropriation of gaze by Clarice Starling, played by Jodie Foster.

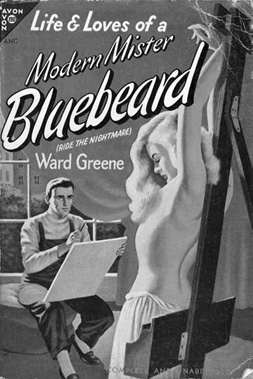

As stills from this film show, the camera is used to effect, but now by Bluebeard’s wife. The film plays in postmodern ways with adaptation issues, using cut paper figures digitally created and employed in a three-dimensional environment. Courtesy of James Merry.

In Thomas Harris’ novel The Silence of the Lambs14 the serial murderer Jame [sic] Gumb has inherited a house with a basement “maze” (1988, 137, 203) in which he rears exotic butterflies, has chambers of tableaux made of corpses, and keeps the women he kidnaps in order to “harvest” their hides for his own metamorphosis. He is making “a girl suit out of real girls” (163, 320).15 Clarice Starling, a neophyte FBI agent working with her mentor Jack Crawford, is tracing Gumb by means of another serial murderer in captivity: the psychiatrist Dr. Hannibal Lecter. Lecter draws Clarice’s attention to the “first principles” in Gumb’s motivation: he covets; you covet what you see. His basement already contains a number of rooms containing series of “tableaux” (354, 360) he has made with corpses. Gumb clearly sees himself as an artist. Although Gumb is the motivation for Starling’s investigation, the film is centrally concerned with the relationship between Starling and Lecter.

The film is particularly interesting for the controversies between critics who seized upon the character of Clarice Starling and the casting of Jodie Foster in the role as a feminist appropriation of the male detective role and those who see the film as simply a variation on the inherently misogynistic serial-killer genre.16 Starling’s point of view is privileged throughout the film, and she is not punished for looking. At the point where the audience is invited to adopt the traditionally privileged gaze of the killer stalking the female detective in the dark with night vision goggles on, the audience is “punished” for doing so: Starling shoots directly at the camera.17

Jane Campion’s period film The Piano is overtly concerned with deconstructing the mechanics of representation and through it challenging the traditional cinematic gaze. The film contains an embedded “Bluebeard,” represented as the amateur Christmas pantomime produced on a community stage in the New Zealand bush. The wives’ “decapitated” heads poke through a curtain.18 Bluebeard wields his axe in shadow play. The representation is already ironically quoted out of context: the setting is uncanny to the transplanted English; the play and its mechanics of representation are uncanny to the indigenous Maori in the audience, who disrupt the performance to “save” the threatened women. At the same time, the frame story of Ada, her husband Stewart, and her lover Barnes is also a Bluebeard story. As in the fairy tale, there is an indelibly stained “key,” which in this case is the proof of Ada’s infidelity with Barnes: she burns a message into a piano key for Barnes, who cannot read, but the message is delivered to her husband Stewart instead. The key is then replaced with Ada’s own finger. A shift has occurred between Perrault’s “Bluebeard,” deconstructed and now “harmless,” and Grimms’ “The Robber Bridegroom,” the “real” story and not harmless. The shadow play of pantomime is revisited in the brutal dismemberment of Ada by her husband, cutting off her finger with his axe. Again, the film thematizes the cinematic gaze. Barnes lies under the piano to gaze at Ada; what begins as exploitative is then transformed into complicity as Ada becomes dependent on Barnes’ gaze to play. Stewart is also shown peeping through a crack in the wall and then another in the floor, watching his wife’s infidelity with Barnes. As Sue Gillett summarized: “It is able to offer female spectators a kind of sympathetic engagement with and confirmation of their subjectivities along with an escape from the usual sorts of containment they receive in patriarchal cinema” (1995, 287).

The feminist and revisionist use of the Bluebeard tale is typified through the contemporary work of both Angela Carter and Margaret Atwood, who both have made repeated use of the tale in various ways and across a range of genres.

Angela Carter’s revisionist use of the Bluebeard story in “The Bloody Chamber” (1979), titling that collection, can be set in the context of her translations of Perrault’s “Blue Beard” and editing of Virago collections to include “Mr. Fox” and “Old Foster,” as well as allusions within other of her fictional works.19 The most obvious revision of Perrault’s story in “The Bloody Chamber” is the very point on which Margaret Atwood objects to the French version of this tale: the rescue of the heroine. In Perrault, the wife’s soldier brothers ride in to kill Bluebeard in the nick of time. In Carter’s story, it is the heroine’s own mother who rides up over the causeway and shoots Bluebeard between the eyes, thereby rescuing her daughter. It is a decisive comment on the original, and one that revises not only Perrault’s story, but the rules of the fairy tale genre, which dictate that mothers abandon their daughters either actively or by default when they die or are “disappeared” from the tale. It is this moment celebrated in the woodcut by Corinna Sargood, a frequent illustrator of Carter’s works, in which the avenging mother is in the foreground, depicted in the act of shooting Bluebeard.20 The antiquated style of the woodcut itself echoes nineteenth-century fairy tale illustration, reflecting the collection’s strategy of revision to a traditional model.21

But while the punchline is most obviously revised, the story also offers another defamiliarizing viewpoint: female complicity in masochistic relationships through first person confessional narrative. The story is set in the early twentieth century (and is saturated with the aesthetics of fin-de-siècle decadence).22

Atwood has often stated in interviews that she read the unexpurgated Grimms at the influential young age of six and that she “loved it.” She focused her comments on the heroine’s capacity for self-rescue in these stories, explicitly comparing them to the French versions: “The unexpurgated Grimm’s Fairy Tales contain a number of fairy tales in which women are not only the central characters but win by using their own intelligence. Some people feel fairy tales are bad for women. This is true if the only ones they’re referring to are those tarted-up French versions of ‘Cinderella’ and ‘Bluebeard,’ in which the female protagonist gets rescued by her brothers. But in many of them, women rather than men have the magic powers” (1978a, 115). She stated elsewhere that “Fitcher’s Bird” is her second favorite tale (1978b, 70–71), and that “Nobody raps her knuckles for being curious” (1998, 34). She went on in this essay to analyze the heroine’s symbolic bird transformation, shedding her bodily form and adopting the guise of her soul-form, summarizing: “In fact, she accomplishes her own resurrection. It’s a powerful feat, and if this is how it’s done, we should all start collecting honey and featherbeds immediately” (36).

Atwood’s poems “Hesitations Outside the Door” (1971) and “The Robber Bridegroom” (1984b), the short story “Bluebeard’s Egg” (1983a) that titles the collection, and the novel The Robber Bride (1993b) as well as allusions within other of her works and several watercolors all testify to an enduring interest in the Grimm version of the tale.23 The early novel Lady Oracle (1976) features an overtly gothic subplot drawing on the Bluebeard tale; her novel Bodily Harm (1981) had a working title of The Robber Bridegroom; and a section of the short fiction “Alien Territory” (1992) is a retelling of the story, beginning “Bluebeard ran off with the third sister, intelligent though beautiful, and shut her up in his palace” (82). Throughout these works, Atwood was preoccupied with “Bluebeardian sexual politics,”24 female transformations, and escape strategies and consistently worked metafictively. In Atwood’s terms, engaging with the story is always a dangerous business, but as Sally, the protagonist of “Bluebeard’s Egg” discovers, ignorance is much more dangerous.

“Bluebeard’s Egg” uses a very obvious technique for metafiction by having Sally enrolled in a creative writing course, “Forms of Narrative Fiction.” When they get to the folklore section, the teacher reads “Fitcher’s Bird” to the class, and the students are asked to rewrite that story from a different point of view. Sally focuses on the egg. In the frame story, she thinks of her husband as this egg: “blank and pristine and lovely. Stupid too. Boiled, probably” (159). But Sally is forced to confront her preconceptions when she discovers that Ed is a man with secrets.

This story is a useful emblem for the revisionist strategy women writers often use: rewriting a known story from an unfamiliar point of view, defamiliarizing the intertext and opening it up to new readings.25 At the same time, this strategy often allows a previously silenced character a voice of their own. Individual fairy tales have all been explored this way, but each revision of a traditional fairy tale simultaneously comments on the entire corpus and the constructions of the genre itself. The cautionary note in Atwood’s story is when Sally misreads her own marriage in the light of an apparently demystified Bluebeard story. Taking her cue from Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey in this and other of her fictions, Atwood suggests that domesticity is the territory of contemporary gothic, rather than the sign of its absence.

In the poem “Hesitations,” Atwood’s metafiction is signaled by the unreliable speaker and by the ability to propose an “Alternative version.” The poem posits the “house” of the Bluebeard paradigm as a third party, but one beyond Bluebeard’s control. Bluebeard’s own story is not expressed architecturally so much as determined by it (reminiscent of the felicitous rooms of Museum Piece No. 13 [King 1945], which determine what happens in them). The house seems to dictate the terms of the relationship that takes place inside: “Whose house is this / we both live in / but neither of us owns” (1971, 135). Another familiar Atwoodian gesture reflected here is to depict the Bluebeard as the oppressor, and then deflate that depiction, demonstrating instead a conspiracy between both speaker and so-called Bluebeard to play these roles of victim and oppressor together. The Bluebeard figure is gothicized, then romanticized, but then the apparently passive speaker tells Bluebeard to get out while he can, demonstrating that the roles are trapping them in their respective behaviors. Here, the speaker realizes that the house is purely symbolic: “This is not a house, there are no doors” (137). Finally, in the last two numbered sections of this multi-stanza poem of many rooms, the story in the closed room is knowledge of the other (as it has always been in the Bluebeard story). Both speakers tell lies to the other: they tell stories about what is in the room, each knowing the other lies. The poem, despite its apparent finality, “In the room we will find nothing / In the room we will find each other” (138), remains unresolved. The door is not opened; the binary is a paradox, itself an example of Bluebeardian politics, the dictum of “either /or.” Where the Bluebeard story is fixated on teleology, the closed ending, Atwood’s storytellers are always more interested in the creative possibilities of escape artistry: transformation and self-resurrection.

The many contemporary Bluebeards in English—the pirates and Turks, the lilies and dog breeds—masked somewhat the ever-present wife murderer of fairy tale origin who retreated from early childhood reading and Christmas pantomimes but who persisted in adult art forms. The archetypal shape-shifter, Bluebeard is the aristocrat, the gentle husband, the animal groom, the male psyche, the creative impulse, Death as a groom. The fairy tale invites a postmodern deconstruction, turning the story inside out and making it over again. However, the persistence of reworkings of the tale by artists of both sexes and in different art forms points to its inexhaustibility. The tale cannot be emptied or neutralized by its many postmodern deconstructions. Instead, its enduring themes have been recast to reflect changing preoccupations and forms of expression, and the Bluebeard tale has earned its permanent place in the English artistic landscape.