|Tropes|

INTRODUCTION

A trope is a familiar convention, an idea or visual image recurrent within narratives, whether literary or cinematic. A common thematic trope, for example, would be the pattern of the rise and fall of the mobster in the classic gangster film. We are familiar with the story arc which gives us the rookie criminal, acquaints us with his ambitions, shows us his increasingly serious crimes and reaches its high point at the middle of the film where he has attained the top position in his gang. From there on, it is all downhill; the gangster is betrayed from within or overpowered from without; he dies in a hail of bullets.

Within this recognisable thematic trope, the gangster film also frequently presents smaller visual tropes; Colin McArthur succinctly sets them out in his chapter on the iconography of such films (1972), noting the dark suits and fedoras, rainy streets and big cars as the visible signs of the genre. The gangster genre, interestingly, also has a sartorial trope it often employs: from early works like Public Enemy (1931) and Scarface (1932) to more recent films such as GoodFellas (1990), the rookie marks his achievements in gangsterdom by ordering new clothes Cagney’s Tom Powers in Public Enemy underlines his own transformation, from wild boy to violent man, when he is fitted for a fancy suit.

A range of recurrent conventions can also be found operating across the various films that contain narratives of transformation. As we found with the comparison of the French and American versions of Nikita, Hollywood has found a way to tell the story of sartorial alteration to which it returns again and again: both the narrative of transformation itself, and the methods of showing the change and its effects, recur across films and genres. There seem to be eleven major repeated tropes that persist across such films; seven are thematic and four visual. The first four thematic tropes indicate the ways in which the transformation is achieved, how they are staged, while two concern more internal qualities of the change, and the remaining one importantly qualifies the transformation. The visual traits are recurrent iconographic methods for showing the alteration; these will all now be considered and exemplified in turn.

1) Visible Transformations – The ‘Makeover’ Scene

Somewhat surprisingly, given the focus of these films on external transformation, scenes showing the actual alteration of a character are rather rare. While the ‘makeover’ scene is the most obvious trope of the film transformation, then, it is paradoxically not one of the most common. When the transformation does permit the viewer to witness the work needed to render the ‘ugly duckling’ into the beautiful swan, it is often presented within a musical interlude, a fantasy space outside the normal narrative drives. Here costume can be allowed to halt the flow of the story, as Gaines (1991) warned over-elaborate designs threatened, and the viewer is actively encouraged to enjoy witnessing the suspension of the dominant trajectory in favour of shots of consumer goods cut to a catchy tune.

In Clueless (1995), for example, the heroine Cher (Alicia Silverstone) gives her new friend Tai (Brittany Murphy) a makeover in order to make her more popular. Cut to the up-tempo sounds of a poppy track, the scene shows Tai at first hesitantly but eventually joyously embracing the new her that Cher crafts with the aid of some hair colour, scissors, and loans from her own extensive wardrobe. Cher and her styling assistant, best friend Dionne (Stacey Dash) transform Tai from a lower-class young woman, who fits only with the déclassé slacker group at Cher’s exclusive high school, to a yuppie princess like themselves. While the young woman is marked from her first appearance by her non-designer trainers, baggy trousers and check shirt, Cher’s borrowed clothes enable her to ascend to a higher social echelon within the school and eventually, if only temporarily, to rival the popularity of Cher herself.

In The Princess Diaries (2001), Mia Thermopolis (Anne Hathaway) is groomed in keeping with her newly recognised royal status when famous stylist Paolo (Larry Miller) renders her unruly curly hair sleek and straight, tames her eyebrows, provides mani- and pedicures, all to a funky beat. Similarly, the transformation of the heroine, Valerie, in Earth Girls are Easy (1988) is encompassed within the space of a full-scale musical number. Valerie has detected a lack of interest in her fiancé Bob and asks her boss at the Curl Up and Dye beauty salon, Candy, for advice. Candy confidently leads her into the public space of the salon and calls on the other customers and assistants to help: ‘Come on everybody, we’re doing a makeover!’ She then sings the song, ‘Brand New Girl’, as Valerie is rendered less ‘wholesome’ and more sexualised. Her red-brown corkscrew curls are straightened and bleached and her brown eyes changed with blue contact lenses, so that Valerie seems to be a completely different, as well as a Brand New, Girl. Candy’s idea is that if Bob is straying, Valerie should be the different girl with whom he dallies. A more overt sexuality is the ticket to increased popularity, for Valerie as well as for Tai, whose rather androgynous original look is discarded for a more feminine appearance.

A similar arc of transcendence from outcast to popular through the right outfitting can be found in the short 1935 Disney cartoon, The Cookie Carnival. This eight-minute fantasy whimsically presents a parade and beauty contest in Cookie Town. After a march-past by various kinds of humanised biscuits, we meet our hero, a hobo gingerbread man. He meets a gingerbread girl who is sobbing because she has nothing to wear to the parade. Like Cinderella, these sartorial woes are relieved by a Fairy God-(father) figure, as the gingerbread man takes pity on her plight and confirms that she will not only go to the party but be crowned Cookie Carnival Queen. He then transforms her, using tools in keeping with the cookie theme. First he turns her hair from drab brown to gleaming blonde with the aid of icing, artfully twirled into a long curl on one side. He replaces her plain dress with a gown made from blobs of frosting, over a petticoat made from a cupcake case, decorated with cookie sprinkles as jewels. The icing sugar from a marshmallow acts as face powder while rouge and lipstick are supplied by more sprinkles; as the finishing touch, the new beauty is allowed to admire herself in the shiny mirrored surface of a lollipop.

We can note here that Tai, Mia, Valerie and the gingerbread girl all have helpers who effect the external transformation for them; not all of the films where we are shown the transformation scene rely on the benevolence of an outside agent, however. In The Major and the Minor (1942), the central character Susan Applegate (Ginger Rogers) creates an outfit which transforms her into a younger version of herself in order to travel half-price on a train. Realising that she cannot afford the fare home and seeing a nine-year-old girl being given half fare, Susan retreats to the ladies’ room in the station and contrives a rejuvenating outfit. Wiping the makeup off her face, she rolls up the waistband of her skirt to make it shorter, swaps her heels for flats, makes stripy socks by cutting up a jumper, and finally emerges with her hair in plaits looking shy and gamine.

Similarly, in two Clara Bow vehicles, It, and Hula (both 1927), the central female herself again achieves the revision. In It, released in February 1927, Betty Lou Spence (Bow) works in a department store and is attracted to her boss Cyrus Waltham Jr (Antonio Moreno). Asked out by his friend Monty (William Austin), Betty Lou agrees if they can go to the Ritz, where she knows Cyrus is dining. Monty reluctantly agrees, and Betty Lou goes home to sort out her outfit. Viewing her wardrobe critically, the young woman decides that her best option is the plain black dress she wears to work. She then acts decisively to achieve her goal of a fashionable outfit: picking up the scissors, she cuts away at the dress while still inside it, cutting a deep V neckline and removing the sleeves, until it reveals itself (and her) as a more stylish and desirable item. The comparable scene from Hula (released August 1927) comments on the earlier film; here Bow’s Hula Calhoun models an expensive dress for her beau. When he hints that he doesn’t like it, she cheerfully tears handfuls of the fabric away until it reveals more of her. Again the accent is on suiting herself rather than the sanctity of any existing dress form; in Bow vehicles, the clothes exist to be modified to suit their wearer, rather than to confer on her a predetermined image.

The 1994 Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicle, True Lies, contains a very similar scene in which the character played by Jamie Lee Curtis attempts a remake, drastically altering her dress while wearing it to effect a similar change on herself. In this film, Helen Tasker (Curtis) does not know that her husband Harry (Schwarzenegger) is a government agent. Feeling alienated from her spouse, she is almost seduced by a lothario pretending, by coincidence, to be a government agent, one who is seeking to recruit her too to a similar post. Once her husband finds this out he decides to punish his wife by calling on her to perform an undercover job: he tells her to come to a smart hotel dressed in her sexiest outfit. Helen duly arrives but examines her reflection critically in a hotel mirror just before the rendezvous. She decides the dress she had chosen – black and formal – is too frumpy, and tears off the puffy sleeves, before rending several inches off the hemline. With the dress purged of its more bourgeois detailing, she feels ready to tackle her assignment. While the narrative shows Helen obviously being manipulated by her husband into thinking she must dress differently in order to become a Mata Hari, it yet allows her through her own agency to alter her appearance. This is a significant moment within the film as Helen has until now been marked by her passivity, as much as her frumpy overlong skirts and drab shapeless cardigans. Furthermore, tearing up the black dress to make it more overtly sexy reveals not only Helen’s desire for a more exciting life and marriage, but also Curtis’s trim star body. This marks another of the defining features of the filmic transformation when it employs a star as the central character needing to be changed: the return of the familiar star in her customary form to her audiences.

Just as Bette Davis is hidden beneath the padding and heavy eyebrows in 1942’s Now Voyager, so Curtis, whose fame in the 1980s and 1990s was heavily predicated on exposure of her very wrought body, is hidden for the first part of the movie under shapeless, all-encompassing clothes which conceal her shape. In both films the viewer waits impatiently for the first sight of the star as her familiar self. This can set up an alternative trajectory to the dominant narrative one, creating a story interested in the changes in costume and body rather than plot developments; as explored in the previous chapter, the wardrobe choices in both films are allowed the potential of establishing an oppositional narrative running separately from the main one. One of the chief pleasures of the transformation thus consists in a dual act of concealing and revealing: the famous star is first hidden, swaddled in unbecoming outfits or heavy body padding until the transformation scene reveals her in her more usual starry glamour.

Another recurrent trope is the reaction of men to the alterations. Their approval is the proof that the metamorphosis is complete and has been successful. Tai’s metamorphosis in Clueless is met by male approval at school the next day; Valerie’s straying boyfriend Bob is aroused by her new look, and the gingerbread girl is crowned queen of the Cookie Carnival by the ecstatic unanimous decision of a panel of male judges.

The transformation scene from Moonstruck (1987) similarly portrays the woman as becoming more attractive to men through her cosmetic alteration. Loretta (Cher) is a quiet, hard-working widow, affianced to Johnny Cammarini (Danny Aiello). When she meets his devil-may-care brother Ronny (Nic Cage) Loretta feels a new passion, both for him and life; after they have slept together once, she tells him she cannot see him again but he begs her to accompany him to the opera; after this one-time date he will leave her alone. Loretta agrees. Later she goes to the neighbourhood hairdressers (knowingly called the Cinderella Beauty Shop) and commands the attendant to ‘Take out the grey’. Loretta is transformed in the salon from a respectable widow with greying hair in a bun to an attractive woman, her newly raven hair styled into a bouffant do, eyebrows trimmed and makeup warming her pale lips and eyelids. While she portrays this transformation to the women in the salon as being appropriate for going to the opera, Loretta is really remaking herself as a person interested in life. As she leaves the salon two men exclaim about her looks – ‘Wow, look at that!’ Loretta hears this and seems heartened, rather than annoyed, at being reduced to an objectified ‘that’. While he had been attracted to her before this self-revisionist exercise, Ronny is also affected by her transformation, gasping in astonishment at her new look.

The success of Loretta’s transformation can also be measured by the fact that it returns the star, Cher, to us in her familiar glamorous state. Like the masquerade of the female star in Now Voyager and True Lies, part of the appeal of Moonstruck is the suspense set up by the unorthodox appearance of the star. Loretta dresses in a modest and self-effacing manner, quite the reverse of the star playing her; while her opera dress does not emulate or evoke the frequently shocking outfit choices made by the star – for example, her infamous Bob Mackie outfits worn for successive Academy Award ceremonies – the transformation sequence does restore the star’s customary dark hair and carefully made-up face.

The films discussed above come from a variety of genres, indicating that the transformation theme and its concomitant tropes traverse generic boundaries. Other films which include the on-screen metamorphosis include the thriller, The Long Kiss Goodnight (1996), teen-pic The Breakfast Club (1985), historical drama Marie Antoinette (2006), superhero spoof My Super Ex-Girlfriend (2006) and war/action oddity, G.I. Jane (1997), as well as more obvious ‘makeover movies’, Miss Congeniality (2000) and Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day (2008). Each of these employs the occasion of the female’s remaking, whether by herself or by others, in order to advance the action as well as providing an occasion for spectacle. Marie Antoinette, for example, uses the moment to show the Austrian princess being claimed by the French court; their ownership of her is enacted by their disposal of all her clothes and personal effects. While the stripping away of the layers of skirts and petticoats shows the princess at her most vulnerable, away from home, claimed by a foreign and seemingly hostile people who, as we know, will eventually go on to cause her death, the literal stripping of the actor playing the princess, Kirsten Dunst, displays her naked body also to the camera and viewer. The unwarranted shot of Dunst naked is included as an attempt to render the exigencies of history more interesting, more immediate, to a modern audience.

Both The Long Kiss Goodnight and G.I. Jane play with the audience’s awareness of the star persona of their lead actors by a reversal of the trait, mentioned previously, of withholding the star in her familiar guise. Both films instead feature the on-screen alteration of the star from her familiar appearance to a different one, and in both this is achieved through cutting off the hair. The heroine of The Long Kiss Goodnight (Geena Davis) is a government agent; rendered amnesiac, she had settled in a small town, and made a life there for herself and her child. Her memory begins to return under pressure; finally an outbreak of violence against her awakens her former persona and she fully emerges, dismayed at the domestic, maternal woman she has become. To announce the return of her ‘real’ self, she cuts off and bleaches her hair, and begins to wear more assertively sexual clothing.

While Samantha/Charlie in The Long Kiss Goodnight displays different versions of femininity, based around a sexual/maternal dialectic embodied through hairstyles, Jordan O’Neill (Demi Moore) in G. I. Jane similarly demonstrates dual, warring, views of the feminine, with her ‘before’ (long flowing) and ‘after’ (shaven) hair. Moore’s on-screen shaving of her own head is narratively explained as confirming her commitment, as the lone woman Navy Seals recruit, to being treated solely as a soldier and not as a female one: it is a demand for equality. However, the visual spectacle of a top A-list star significantly and truly (no head double) altering her looks in such a radical way swamps the act as plot point and becomes instead a part of the publicity1 and mythology of the film.

While the on-screen scene of transformation is, then, quite rare, those instances where the film does play it up choose to do so in order to highlight a range of issues – femininity, desirability, popularity – but are always aware of the spectacular nature of what they show. By contrast, the invisible transformation determinedly withholds the spectacle of the change being performed; more numerous than the shown metamorphosis, these concealed moments of alteration will now be discussed.

2) The Invisible Transformation

The invisible alteration is much more commonly found within Hollywood films. The process by which the changes are wrought is withheld here, so that the viewer is granted the ‘before’ and the ‘after’ with no intermediate ‘during’. But why do films choose to deny viewers the pleasure of seeing the changes effected? Examining examples of the trope at work reveals there are various reasons for this decision.

Most frequently where the actual work required to render the woman altered is not seen, the transformation is withheld in order to create suspense or surprise, or indeed frequently both: the viewer is worked upon to wonder what the alteration will have achieved, and the moment of revelation is filmed in appropriately grand style. In the 1938 novel, Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day by Winifred Watson, a dowdy out of work governess has her life totally transformed in the space of 24 hours; after a day of excitements, she finds herself about to be launched on the London night club scene in borrowed finery. Her two mentors, actress Miss LaFosse and beautician Miss DuBarry, prepare to make up her face and dress up her body, but Miss Pettigrew herself elects an invisible transformation:

Miss DuBarry sat her in front of the mirror.

‘No’, said Miss Pettigrew firmly, ‘I think not. I’d rather see the final result: nothing spoiled by seeing the intermediate stages, thank you.’ (Watson: 93)

Just as Miss Pettigrew here chooses to skip seeing the work necessary to turn her into ‘A woman of fashion: poised, sophisticated, finished, fastidiously elegant’ (98), a move which the 2007 film version of the book retains, so films which select the invisible transformation elide the labour to preserve the sense of mystery which might be dispelled if it were shown. The transformation can seem more magical if the work needed to accomplish it is kept, like the tricks behind a magician’s legerdemain, out of sight. A similar instance of the transformative labour being withheld occurs in 1921’s Forbidden Fruit, where the narrative renders the change in poor seamstress Mary (Agnes Ayres) even more magical since she does not have to spend money to attain the glamorous wardrobe which achieves her transformation. Tapping overtly into the story of Cinderella, Forbidden Fruit shows Mary being inveigled into masquerading as a wealthy young woman. The costumes necessary to this imposture are provided by her employer, Mrs Mallory, a society matron who needs to procure ‘the prettiest girl in New York’ to entice her husband’s potential business partner into staying in town. Mary ironically therefore gets to don the gowns she usually alters and mends for other women; DeMille stresses the magnificence of the sumptuous gowns on loan to Mary by having them designed by famous Parisian couturier Paul Poiret.

The film can also be seen to be making rather subversive use of the Cinderella story, since Mary is a married woman rather than a maiden. Her husband is a gambler and petty thief, easily made jealous and not above hitting her when riled. The plot of the film happily arranges to have him killed off so that Mary can legitimately enjoy the benefits of her relationship with her ‘prince’, the wealthy young captain of industry she secures through her new glamorous appearance. The film not only echoes the Cinderella tale through its basic narrative structure; it also contains extensive fantasy sequences which directly enforce the parallel by showing Mary as Cinderella, both by her kitchen fire and, after her metamorphosis into a dazzling princess, at the ball. These lengthy scenes are intercut into the main narrative, couched as the imaginings of Mary or her ‘prince’, and feature even more outlandish and sumptuous outfits and settings than the ‘modern-day’ scenes.

A film’s generic allegiances can also dictate using the invisible transformation. In the thriller, Final Analysis (1992), two sisters are involved with a psychiatrist, one therapeutically, the other sexually, but both with an ulterior motive. When the woman who has slept with the psychiatrist then kills her husband while suffering a bout of ‘pathological intoxication’ and is put in prison, she is forcibly transformed out of her usual glamorous and sexy outfits into the institutional uniform of denim shirt and trousers. This levelling outfit, which renders all prisoners visibly similar, then enables the woman to escape by trading places with her sister. The film wryly makes use of the fact that one blonde woman is easily interchangeable with another, as Kim Basinger substitutes for Uma Thurman, and escapes confinement by simply changing her clothes. The transformation which allows this plot manoeuvre is not shown in order to create suspense and surprise for the viewer.

But the suspense/surprise combination need not be used as the hinge for narrative action; it can be evoked to involve the viewer more with the character. For example, in Now Voyager, the central character, Charlotte, all clumpy shoes and unkempt eyebrows, is taken off to recuperate from a nervous collapse to Cascades, the rest home of her medical adviser, Dr Jacquith. While there Charlotte is given a better diet and prompted to exercise, so that she already looks healthier when her sister in law visits her; her glasses are also abruptly broken by Dr Jacquith to prove to Charlotte that she does not need them, but has been hiding behind them for years. Significantly, she claims that she feels ‘so undressed without them’. The glasses have become part of the old Charlotte’s wardrobe and must be removed as part of the new Charlotte’s transformation. Dr Jacquith states that ‘It’s good for you to feel that way’, preparing the viewer for the more sexualised and sensuous outfits that Charlotte dons once her cure is underway.

While Charlotte seems improved at Cascades, she is still recognisably the same unhappy woman she was back in Boston at the home of her domineering mother. Jacquith mandates a cruise to establish her as a totally rejuvenated person, and it is here that the real transformation takes place. The scene, as noted before, restores the famous star Bette Davis to her public in her familiar form. Charlotte is on board the ship; the other passengers are waiting for her to come on a shore visit. Their waiting and suspense at meeting the enigmatic ‘Miss Beauchamp’, Charlotte’s shipboard alias, are felt by the viewer too; Charlotte’s entrance, and progress down the stairs of the ship to where the others await her, acts as her ‘big reveal’. The arrival of the transformed Charlotte at the top of the gang plank evokes her original entrance in the film, when she slowly made her way down the stairs in her mother’s house, the camera focusing on her thick ankles and heavy shoes. The work necessary to change Charlotte from her old unhappy self to her braver new persona, wary and fragile, but out in the world, is not elaborated beyond Jacquith’s breaking of the glasses, and the interim scene where Charlotte seems healthier and more slender. The film employs suspense instead of showing scenes where the transformation is achieved.2

Now Voyager 1: ‘Before’ the transformation which Charlotte needs

Now Voyager 2: ‘After’ – chic ‘René Beauchamp’ steps out

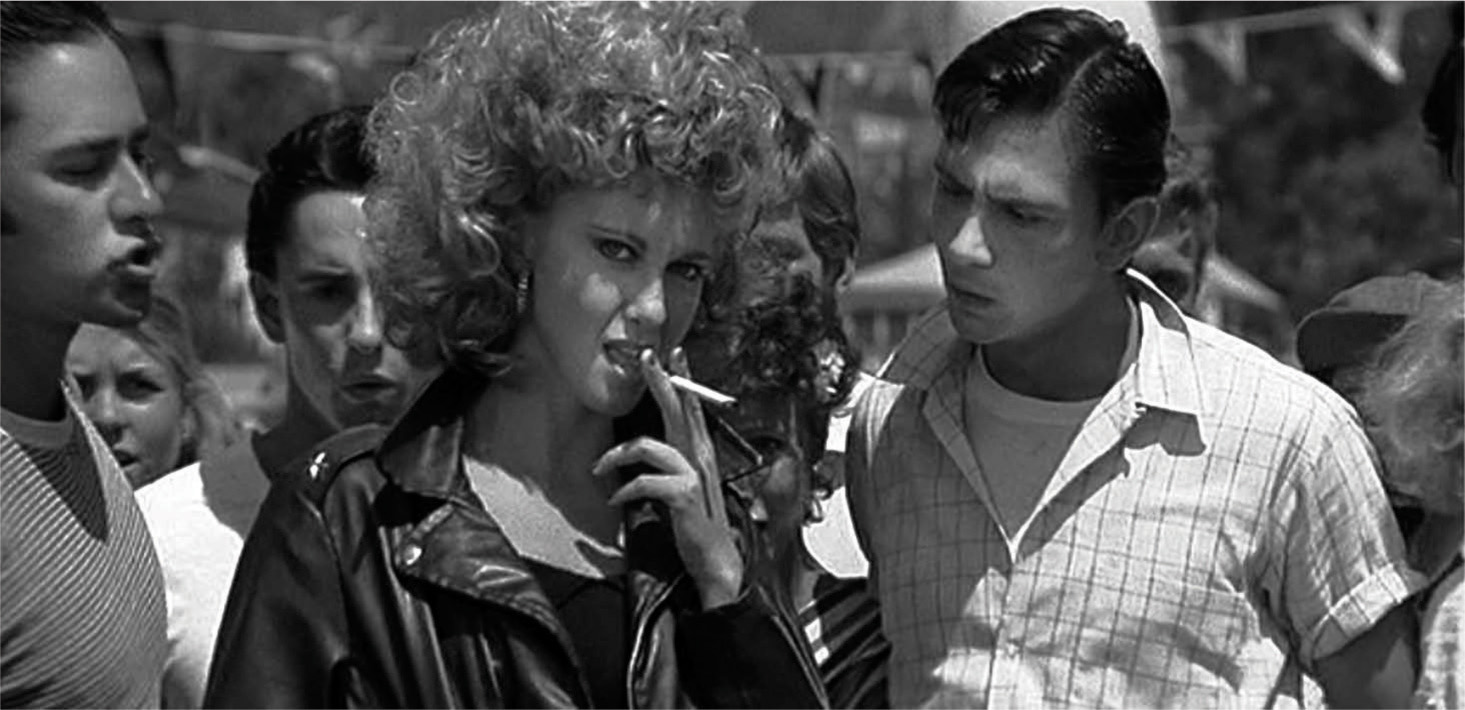

Grease (1978) similarly chooses to withhold the scene of Sandy (Olivia Newton-John) changing from good girl to bad. Danny (John Travolta) has been successful in a car race, and everyone is celebrating; only Sandy seems sad. Having quarrelled with Danny about their relationship, Sandy has watched the race from a distance. Frenchy (Didi Conn) who has worked in a beauty parlour, kindly comes over to her, and Sandy asks for her help. This, and her comment to herself, in the form of a sung soliloquy, prepares the viewer for her transformation; reprising the song sung mockingly about her earlier by the other girls, in which she is compared to Sandra Dee,3 the 1950s starlet, Sandy bids farewell to her nice girl persona.

In the next scene, Danny appears having traded his T-Bird leather jacket for a letterman jacket (the exterior sign that he has tried to take one school subject seriously and has earned some credit in track running). The other T-Birds view this garment – softer, knitted and white – as a betrayal, but do not have long to worry – Danny’s partial transformation is very short-lived. For just then the new Sandy arrives.

Sandy’s before and after are so radically different that no ‘during’ is necessary; the point is to surprise both Danny and the viewer. Had the film elected to show Frenchy changing Sandy’s hair, makeup and wardrobe, the mingled suspense and surprise of this moment would be lost. The enormity of the transformation is best revealed by having it sprung on the viewer rather than worked up to by degrees. Gone are Sandy’s neat blonde bob, her wide-skirted pastel dresses, ankle socks and saddle shoes. In their place are a (very anachronistic, 1970s) curly perm, skin-tight black trousers, off the shoulder top and red high heels. Sandy has consciously changed her exterior appearance from a good girl to a vamp; while her behaviour shows that she has not yet changed her inner self, her readiness to look sexually experienced indicates to Danny that she is now willing to renegotiate about this, the major cause of conflict in their relationship.

Another reason that the work necessary to turn Sandy from a pure maiden into a raunchy-looking vamp is withheld is because this makes the transformation not only more of a surprise, but also more magical, more like a fantasy. Danny is discussing his own partial transformation with his fellow T-Birds when she arrives; he has just told them that he has ‘lettered in track’ to get the jacket, evoking the horrified response, ‘Danny Zucko turned jock?!’ Danny explains that though ‘you guys mean a lot to me, it’s just that Sandy does too and I’m gonna do anything I can to get her, that’s all’. As two of the gang stare at Danny in hurt bewilderment, the other looks away – and sees the transformed Sandy. The reverse shot that would reveal her is withheld, however, so that the audience views his startled face, then his slap on the shoulder of his friend, his startled look of surprise and so on, through the T-Birds ranks. Before we can see Danny observe the surprise, however, we are at last given, to accompanying wolf-whistles, the sight of Sandy’s legs, now clad in skin tight black satin, striding through the crowd. At last we see Danny turn, see the woman, look her up and down and then recognise her: ‘Sandy?!’

After the whole gang is reconciled and another dance number is encompassed, Sandy and Danny roll up in his car and proceed to fly off into the sunset, both clad in leather jackets. There seems to me no reason why a film which can end with this fantasy of eternal youth and freedom, signified by the bright blues skies, fluffy clouds and flying car, should not also be prepared to fantasise about the good girl magically turning bad rather than breaking up with the boy. Like Danny’s avowal of his feelings for Sandy to his friends, the film wants the couple to be reinstated to attain a happy ending and is ‘gonna do anything [it] can to get’ them together. Transforming Sandy from prude to vixen without showing any intervening stages is then not only important for the surprise of the scene, it is entirely necessary in order to maintain this fragile bubble of fantasy, which might rupture if made to accommodate scenes of hair perming and ear piercing.

Grease: ‘Bad girl’ Sandy makes her appearance at Rydell High

Musical interludes were seen to be significant for the enactment of the visible transformation in the last section and are no less prominent in the trope of the unseen change. In Madame Satan (1930) and Silk Stockings (1957) the alteration in the central female is accompanied by or encompassed within a musical number.

Madam Satan features Angela Brooks (Kay Johnson) whose husband Bob (Reginald Denny) has been straying with singer Trixie (Lillian Roth). After meeting Trixie, Angela decides to fight to keep Bob. She goes, anonymous and masked, to the party on a dirigible that Bob’s best friend is hosting, announcing herself as Madame Satan, and proceeding to vamp her own husband. While Angela’s metamorphosis is not in terms of quality of clothing, as some others of the transformations considered here are, since as a rich woman she always wears furs, jewels and couture, the alteration is significant in terms of sexualisation. Like Sandy in Grease, Angela must fake being a ‘bad girl’, sexually knowing, in order to keep her man. Again like Sandy, the external transformation occurs before the internal experience the exterior seems to guarantee: Grease’s Sandy appears a sexually knowing temptress before being initiated by Danny. This external change before the internal one is necessary in order to allow the internal one: looking like a vamp is necessary if Sandy is to become one. While Madam Satan presents a married woman, rather than the virginal girl, as its central female, the film viewer is still encouraged to read Angela in maidenly terms: her frequent wearing of white, and modest demeanour, testify to a lack of sexual experience in her married life. As Sandy is contrasted with the Pink Ladies, especially sexually active Rizzo (Stockard Channing), Angela is contrasted with lively flirt Trixie. Dressing more like bad girls allows the good girl heroines to ensnare the men they desire and ensure they themselves become sexually knowing. In this way, the appearance of both women forecasts the way they will become and attracts the man who is the necessary tool of that becoming.

Again the work rendering mild Angela into wild Madam Satan is withheld for suspense and surprise; the audience is invited onto the dirigible first so that Madam Satan’s grand entrance is staged for us, as well as the other party guests. We are then surprised to see how altered she is, both in appearance and demeanour. Adopting a faux French accent, Madam Satan has the courage to make a spectacular entrance, announce herself in song and then insult Trixie and intrigue her husband, emboldened since the voice, mask, name and costume hide her real identity.

Silk Stockings is a remake of Ninotchka (1939) and retains its story: a dour Soviet officer is transformed into a happy romantic when she falls in love in Paris. In both films the external sign of her ideological alteration comes in the form of the acquisition of material goods. The 1930s heroine, played by Greta Garbo, appeared after her metamorphosis in a ‘ridiculous’ hat she had previously criticised for its uselessness. Romance makes her realise beauty is important too. The musical version, featuring Cyd Charisse in the Ninotchka role, opens up the scene into a much more elaborate dance number, where the woman retrieves her illicit new purchases from their various hiding places around her hotel room: earrings in the typewriter and a hat in a jar. Her shedding of her drab green army uniform and trying on of the new filmy, feminine and seductive stockings, shoes, slips, dresses, is reminiscent of a caterpillar shedding its chrysalis and becoming a glittering butterfly; falling in love has awakened her need to look and feel more feminine and her purchases enable her to do this, and to attract the man’s approval for this alteration.

As noted, the usual transformation trajectory is one that connects sexual desirability with the appearance of sexual experience, and thus one which prompts the woman to become more overtly sexualised in her dress. The reverse route can occasionally be found, however; in Pretty Woman, Little Shop of Horrors (1986) and The Last Seduction (1994) the woman’s transformation takes the form of toning down her usually overt sexuality.

When several different alterations occur to the woman’s appearance and dress style, the incremental changes, the varying degrees of alteration from before to after, are registered in different scenes. In My Fair Lady (1964), for example, based as noted on the Pygmalion myth and thus on one of the foundational texts of the transformation theme, Eliza’s dirty and multi-petticoated outfit which she wears when meeting Higgins is taken away by his maids and burnt once she lives in his house. Her subsequent outfits are all neat, clean and becoming, as is her hair, although none of them approach the glamour of the two (designed by Cecil Beaton) that she wears to Ascot and then to the final ball which wins Higgins his wager. While Rachel Moseley has written eruditely on the recurrence of the Cinderella myth in star Audrey Hepburn’s film roles (2003), it should be noted that the transformation in My Fair Lady is an incremental one, rather than a radical metamorphosis. Further instances of incremental change, and thus of multiple small transformations which are not shown, occur in The Women (1939) and Mahogany (1977). In the former (and its two remakes, The Opposite Sex (1956) and The Women (2008)), the frequently found character of the disappointed wife is found; Mary’s husband, like Angela’s in Madam Satan, has been having an affair. Over the course of the 1939 film Mary transforms from a relaxed and confident wife, suiting her leisure activities to those of her husband in checked shirts and corduroy skirts which evoke his hunting garb, to a more poised and autonomous woman with a wardrobe of outlandish evening dresses at her disposal and a perfect manicure of ‘jungle red’. Tracy, the sometimes-eponymous heroine of Mahogany, is shown at various stages of her career as a model and designer; the film begins with the woman, elegant in a mahogany-coloured self-creation poised on the eve of her greatest success as a couture designer, as her Kabuki collection is hailed as a triumph. The film then steps back in time, and in levels of glamour, as it follows Tracy struggling to hold down a day job and take classes in fashion drawing at night. In these scenes, set in urban Chicago, Tracy’s outfits are simple and plain, obviously inexpensive, day dresses. When she accepts the offer of a famous photographer to visit him in Rome and become his latest muse, however, her costumes begin to become more extreme in terms of design and colour. The changes are not a ‘makeover’; the alterations that occur in Tracy’s off-camera wardrobe and hairstyles occur gradually and incrementally, as those in her work outfits as a model alter radically and swiftly.

The films that use the invisible transformation trope do so, as has been seen, for a variety of reasons. Predominant amongst these is the evocation of suspense and the surprise when the change is finally revealed; in the films discussed above, the impact of the radical alteration would be lost if the work necessary to achieve it was shown in detail. Not showing the self-revision undergone by the women in these scenes also allows the change to seem more magical, more like a fantasy, although, by contrast, when the changes are shown to occur in increments, gradually, it can seem more like real-life modifications of personal style.

While the past two sections have dealt with films which choose to show, and to withhold, the moment which renders the female star transformed, as has been seen, a third option is open to film-makers who decide to use the metamorphosis motif. In this, very popular, trope, a particular form of the labour required to change the woman – shopping – is dwelt on at length, as will now be considered.

3) The Shopping Sequence

The previous two sections noted that on-screen depiction of the transmutation is quite rare, and that films tend to prefer to make use of the surprise and suspense that can be generated by not revealing the actual work of change. By far the most numerous instances of the transformation trope, however, concern shopping, which is presented as a kind of transformation in itself. In the films discussed below, simply buying the outfit is enough to initiate its powers of alteration. Just purchasing the skimpy dress, the dizzyingly high heels, is enough, in films, to reap their benefits. Shopping is transformation, these film sequences tell us.

Again frequently achieved during a musical interlude or montage, the shopping sequence not only prepares the central character, and the viewer, for her metamorphosis by displaying the commodities she is purchasing to achieve it; shopping is the very labour necessary to accomplish it. In Gold Diggers of 1935, for example, a musical number with Ann Prentiss (Gloria Stuart) and Dick Curtis (Dick Powell) is the occasion for the woman’s rather unbridled spending, using her mother’s charge account. Although her mother, Matilda Prentiss, is a millionaire, Ann has been deprived of the nice things she feels herself entitled to – dresses, jewellery, fun and boys. In the film’s early scenes she appears in a series of shapeless dresses which do not accentuate her slim body or her bust; with her plain hairstyle and no obvious makeup, she appears more like the rich Mrs Prentiss’ assistant or companion than her heiress daughter. Even Ann’s brother pleads with their mother to let the girl have some nicer clothes. Eventually Ann makes a bargain with her mother – in return for a promise to marry the rich idiot Matilda has picked out for her, Ann gets to ‘have fun’ for the summer. This fun largely consists of being allowed at last to buy and wear the wardrobe of her dreams; any thoughts of meeting men to have fun with are frustrated by the fact that Mrs Prentiss also provides Dick as a chaperone.

Dick at first resents having to be Ann’s minder and objects in particular to going shopping with her. He tells her that if they were sweethearts he would have the right to comment on her clothing and could even serenade her while she made her choices. This brings the scene to its culmination in the song ‘Going Shopping With You’. Dressed in one of her plain day dresses, Ann is allowed to acquire expensive lingerie, diamond jewellery, hats, shoes, gowns; she also gets herself a permanent wave in the beauty parlour, eventually transforming herself, in her new black evening gown and ostentatious accessories, into an icon of excess.

While Ann shops, Dick sings: this is the division of labour between them and allows him to keep up an ironic running commentary on all the expensive goods that she desires. His song also couches their imagined future relationship in terms of things to purchase, including a cottage, a mortgage, and baby blankets, after, of course, a wedding, which is again alluded to by the necessary purchase – ‘On your fourth little finger/A ring’s gonna linger’.

At the end of the scene, surrounded by boxes overflowing with expensive items, Dick sings ‘Behold the finished product! Behold a dream come true!’ Ann’s transformation has been invisible, in that the viewer has not witnessed her perm, or her trying on of any of the clothes. Yet the shopping that has been illustrated acts as the moment of alteration; pointing to Ann, as she holds a pose elevated above him in an elaborate new dress with a large black fan, Dick indicates the modified woman amidst the agents of her change. It is not only Ann’s dream that is embodied on the screen; the film here caters to its Depression-era audience’s fantasies of riches and abundance, allowing its members to feel vicariously as if they had some share in Ann’s bounty since they had been allowed to see it accumulate.

Although shop assistants, rather than a friend, act as the Fairy Godmothers helping to plan and achieve Ann’s new look, the scene acts like the ones in Clueless and Forbidden Fruit to elevate the social status of the woman. Interestingly, in Gold Diggers, Ann has always been the daughter of a rich woman, but now in the appropriate clothes she finally appears one. It is easy to imagine Depression-era audiences revelling in the commodities on show here, and sympathising with dressed-as-poor-girl Ann’s desires to acquire a range of exquisite items. In the shopping scene, the film luxuriates in the opulent goods displayed for the camera and audience and allows a vicarious enjoyment of the spending spree.

Gold Diggers of 1935: The culmination of Ann’s spending spree

Ann’s increased social status, written on her body in the form of more elaborate and costly garments, is matched by her increased sexualisation. While her new clothes do not dramatically reveal her flesh, they do draw attention to her curves, and her new hairdo and use of makeup accentuate a more overt femininity. It is also noticeable that while Dick is pleasant to Ann before her transformation, it is only while escorting her about in her new finery that he falls in love with her and they become a couple. Her plain hairstyle and lack of makeup or accessories in the ‘before’ part of the film, contrast with her later construction as a society beauty through the acquisition of commodities.

While the shopping sequence can stand in for the transformation, visible or invisible, when a metamorphosis scene is provided, it removes the necessity for a lengthy scene of acquisition. In Moonstruck, for example, having shown the beauty professionals at work altering Loretta’s hair, the film seems not to feel it also needs a shopping montage. The woman walks past a store and sees a strapless red dress; she is shown entering the shop and then leaving again with several carrier bags. Arriving home, she unpacks and then revels in her purchases. This is where the focus of the scene is then found: Loretta pours herself a glass of red wine and sits by the fire in her bedroom examining her purchases: lipstick, scarlet shoes, dress, wrap. With soft music in the background, when Loretta begins to unbutton her blouse the scene takes on even more the feel of a seduction, especially when the sexy saxophone begins as she takes off her top. But the one being seduced is Loretta herself; she examines herself wearing her new shoes and wrap, studying herself as though seeing a new woman. The scene’s autoerotic tone is meant to convey Loretta’s long-dormant sexuality and sensuality returning to life, but also displays the easy association of the woman with the products she has purchased. Loretta has turned herself into a wow-worthy ‘that’ by having her hair done; buying expensive new, more sexualised, clothes achieve the transformation, as the reaction, not merely of bystanders, but the new significant man in her life, Ronny, attests.

The importance of music during the transformations was noted in both earlier sections, and indeed the musical interlude is also linked with the shopping montage, as seen in this moment from Moonstruck, the musical number in Gold Diggers, and the comparable one in Enchanted (2007), in which princess Giselle (Amy Adams), newly arrived in New York City, is joyfully taken on a shopping spree by a little girl armed with her father’s emergency-use credit card, an item the little girl declares knowingly is ‘something better than a fairy godmother’. The use of music confirms the connection of the invisible transformation with the magical or fantastic, as discussed in Grease; since shopping is shown instead of (and as) the work of transformation, it is unsurprising to find the musical sequence occupying such a prominent and important position in shopping segments too.

It is noticeable that in these shopping scene transformations, the trajectory has been from the sexual innocent to a more poised and seemingly experienced incarnation of the woman. An earlier film which deals with the same issues and reproduces the same magical transformation through the adoption of different clothing is Cecil B. DeMille’s Why Change Your Wife? (1920). The heroine, Beth (Gloria Swanson) is a prudish matron who refuses to celebrate the physical side of her marriage, and ends up divorcing her husband. Her troubles begin when her husband Robert (Thomas Meighan) tries to spice up their home life by buying her a present – a saucy negligée with matching boudoir slippers and stockings. This garment, draped with ropes of beads, dripping with fur and lace, seems to be a forecast of the type of costumes worn in DeMille’s famous biblical epics from the later 1920s: it connotes the foreign, the exotic and thus the erotic.

Beth rejects the symbolism of this garment however; whereas Sally, the dress shop modiste who models the negligée for Robert, wants to look provocative in the item, and removes the gown’s under-slip so that the sheer fabric shows the maximum amount of skin, Beth replaces the missing slip with one of her own bulky cotton ones, prompting Robert to remark ‘…in the shop, it looked – thinner’. Beth and Sally are contrasted overtly here; the lawful wife wants no physical contact or erotic disturbances in her calm, ordered life, while the eventual girlfriend, Sally, is more than keen for a physical relationship with Robert. The film shows that Sally manages to tempt him to stray through an assault on his senses – her lair features soft furnishings, heady perfumes, pulsing rhythmic music and the lavish provision of alcohol – significantly a liqueur called ‘Forbidden Fruit’. Robert is tempted to kiss Sally and then remembers his marriage vows, but this small error is enough to make Beth divorce him; smelling Sally’s perfume on her husband’s clothes, she insists on a separation.

But Beth really loves her husband and is miserable after he is gone. Having lost him over a disagreement about decency in dress, which has deeper symbolic resonances of her attitude to sex, she receives her moment of epiphany, appropriately, in a dress-shop cubicle. Her aunt Kate is trying to cheer her up after the divorce by suggesting a new wardrobe; Beth claims she hates ‘clothes – and men!’, showing that she is aware how closely the two are involved and how the attraction of one depends on the attractiveness of the other. She then overhears two women in the cubicle next door criticising her dress sense and blaming this for her recent divorce. Beth becomes furious and determines to confound her critics by becoming the ultimate vamp, violently tearing off her own modest clothes and draping herself in new seductive fabrics, ordering dresses that are ‘sleeveless, backless, transparent, indecent’.

Significantly, and illustrating how the shopping sequence works as transformation, merely ordering and selecting these garments is enough to confer the type of active sexuality which Robert prefers and the film endorses as ensuring a healthy marriage. Appearing in a scandalous bathing outfit at an exclusive resort, Beth manages to attract her former husband back to her. While all her behaviour is seen to alter – she is flirtatious, sensual and seeks erotic contact – it is in her dress that the most obvious and radical transformation has occurred, and because of her acquisition of these new garments that she has become a new woman.

Why Change Your Wife? 1: Beth as prudish matron…

Beth eventually wins her former husband back; a coda shows them together again enjoying all the sensual delights she had formerly banned from their home. Listening to throbbing music, dancing together, letting him smoke his cigar and drink in the parlour, the new Beth has one more revolution to make: she slips away and then returns dressed in the original negligée that caused the friction between them. A matter-of-fact final shot shows the servants pushing the couple’s twin beds together again: marriage-sanctioned sex is the result of the wife’s new style of dress.

While the entire film pays witness to the power of clothing to alter oneself and attract others, the specific power of shopping as an agent for change is attested by the scene in the dress shop. Beth can alter her behaviour, swapping prudery for flirtatiousness, simply by a change of clothing: she becomes the woman her husband wants, a totally different personality type, by buying the clothes that type of woman would buy.

Thoroughly Modern Millie (1967) usefully embodies many of the elements accompanying the shopping transformations already cited, and crystallises a new one. Millie Dillmount (Julie Andrews) comes to New York City in 1922 to be a typist. The film’s credit sequence begins with Millie dressed in old-fashioned garb: she wears a grey suit, with a long ankle-length full skirt, lace-up boots and a hat trimmed with flowers over long curled hair. Over the length of the title song, sung by Andrews in voice-over (i.e., not performed by her character within the scene, but over it), Millie transforms from this staid young woman of the 1900s to a dashing flapper of the roaring twenties. First she changes her hair, substituting a bob for her curls, and then changes her outfit and footwear. Finally she gains the flapper’s boyish silhouette.

Why Change Your Wife? 2: …and as sexy spouse

Throughout the scene Millie is prompted to make her purchases by viewing other women already enjoying theirs. She sees the sleek bobbed hairstyles of other women on the street and this gives her the idea to emulate them. Each time she emerges from a shop wearing her new acquisition, she smiles happily at conforming to this latest fashion, but quickly realises there is something else needed before her transformation is complete. Having achieved the correct hairstyle, Millie is content until she notices the old-fashioned length of her hemline and her sturdy boots. Next, exiting a dress store clad in a light grey knee-length day dress, grey stockings and shoes and an iconic twenties cloche hat and rope of beads, Millie is smugly sure of herself, confidently striding down the street until, again, she notices a difference between herself and the other women passing, women who have got it right: their beads hang straight… This scene aptly acknowledges one of the truths about fashion and consumerism: there is always something else to buy. Millie is the ideal consumer, as she constantly monitors her own clothes and accessories against those of others, and spends in order to fit in with them.

Millie also weighs her success as a clued-in shopper by the reaction of men. After her haircut, but before she changes her outfit, she sees two men stare at a well-dressed young woman in the street. One of the men sports a straw hat with a very noticeable polka-dot hatband, and this enables the viewer to identify him again later in the scene, when, once more parading down the street, he and his companion turn their heads to follow another well-dressed female – this time it is Millie, who receives their approbatory glances with a mock bashful lowering of her eyelids and a smug smile.

One final element to note in this sequence from Thoroughly Modern Millie is that it too employs that withholding of the star in her familiar guise that we have noted as a recurrent factor in the transformation. While the audience recognises Julie Andrews’ clear, bell-like tones singing the opening lines of the title song, her appearance at the start is very different from usual; with her long curls and Edwardian clothes, Andrews seems very unlike her usual film persona. Once she has had her hair cut, however, she emerges from the Madcap Beauty Spot to the waiting camera and confirms herself as the star we recognise: her short crop now returns to us the actor as we remember her from The Sound of Music (1965). Although the shorter hair does fit with the time period, the haircut seems more 1960s than 1920s, more designed to evoke ‘Julie Andrews’ than 20s flapper: her haircut is shaped closer to her head than the bob which fits the chronology, such as worn by Clara Bow in It and Hula.

The shopping sequence thus employs elements found in the other transformation tropes such as the musical interlude, the use of male attention as the affirmation of the revision’s success, and the play with the star’s own persona; it also emphasises that the usual arc of change is from modest to sexually overt, prude to vixen, at least in appearances. The shopping sequence falls between the visible and invisible transformations as a means to show the alteration of the central figure; it does not show the labour required to achieve the revolution in looks as the rare, visible, transformation does, but it does supply scenes of effort and labour missing from the invisible transformation. This motif suggests that shopping is the labour that will accomplish the desired change, and it is easy to imagine why this should be such a popular concept. Not everyone has the willpower and stamina to undergo rigorous training, dieting and exercise to achieve a new physique; most people do have the necessary finances, however, to buy a new outfit or a magazine with a radical diet plan in it. By showing us that attaining change is as easy as committing to it through purchasing, the films that use the shopping montage encourage viewers to feel better about themselves by spending.

Using the glamour of stars to sell individual products has a long history in advertising, and it can easily be imagined how the vast distance between the transcendent star on the screen and the lowly audience member was exploited by marketing departments, assuring purchasers that buying a face cream or shampoo would bring the star’s glamour within the ordinary viewer’s reach. The shopping sequence employed in the Hollywood film which features transformation makes the achievement of radical change seem magically easy, encouraging viewers to emulate the stars on screen by buying consumer goods. The reinforcement of the importance of spending can be seen as an obvious message for Hollywood to endorse: it too is in the business of making people buy goods, from the essential movie ticket to various tie-ins. While all film industries, and not just the American mainstream, are in the business of making money, in Hollywood, the overt recognition of this fact occasionally surfaces in the films themselves. In the 2001 romantic comedy Kate and Leopold, for example, there is a self-reflexive moment when the wheels of the plot seem almost audibly to grind to a halt as the heroine, musing over why she has never met the perfect man, reflects on the industry surrounding romantic love:

Kate: …maybe that whole love thing is just a grown-up version of Santa Claus, just a myth we’ve been fed since childhood so we keep buying magazines and joining clubs and doing therapy and watching movies with hip-hop songs played over love montages, all in this pathetic attempt to explain why our Love Santa keeps getting caught in the chimney…

Kate may here be testifying to the difficulty of finding true love in the late twentieth century in New York; she is also rather overtly pointing out that the solution to this difficulty, constantly urged on us, is spending money, whether on magazines, which would feature that new diet or outfit, gym club membership for the outer person or therapy for the inner, or indeed movies themselves. Just as Thoroughly Modern Millie’s heroine is perpetually reminded that, no sooner has she made one purchase than another commodity arises that she needs to buy, the film viewer is constantly encouraged to spend money in an everlasting cycle of self-monitoring, dissatisfaction and fleeting pleasures. Shopping montages give viewers a momentary frisson of contentment as they can vicariously enjoy the fantasy accumulation of abundance; when, as so often, they are cut to the upbeat strains of a nostalgic song, as in the shopping sequence in Pretty Woman (1990), the feelings of positive pleasure that accompany the purchasing involve consumer capitalism in a warm glow, making us feel good about goods.

Very rarely, just as the transformation moment has as its antithesis the invisible transformation, the shopping sequence also finds its shadow-other in film, in the invisible shopping scene. I found one example of this much rarer trope in The Smiling Lieutenant (1931). Here the familiar element of the musical interlude which provides a bridge over a period of time is used again; in this sequence the musical number also acts to distract attention from the strangeness of the scene, a shopping sequence with all of the acquisition but none of the purchasing.

The scenario of the sequence runs thus: Princess Anna (Miriam Hopkins) has married Nikolaus ‘Niki’ von Preyn (Maurice Chevalier), a lieutenant in the Austrian army. Although this is socially an elevation and politically thus a very good move for Niki, he seems cold and uninterested. Anna discovers he already has a girlfriend, Franzi (Claudette Colbert), the leader of an all-girl orchestra. She summons Franzi to the palace for a showdown, but instead of turning into a catfight for the man, their meeting becomes the occasion for Anna’s transformation. During the first minutes of their meeting, while each is summing the other up, judging her appearance and weighing it against her own, the two women are antagonistic to each other, but their conversation and actions revolve around clothing: their sexual and emotional rivalry is displaced onto their outfits. Anna takes Franzi’s jacket politely, as a hostess should, but then throws it on the floor petulantly. Franzi looks the princess up and down coolly and dismisses her outfit as being in bad taste. After this brief skirmish, the two exchange slaps and then both fall onto Anna’s bed sobbing. After a time Anna gets up and gets two handkerchiefs from a drawer; she and Franzi both enthusiastically blow their noses, the matched actions and sobs here reinforcing the idea that they are, underneath their social differences and dress styles, very similar women. They go on to discuss Niki and again the conversation centres around clothing. Anna praises him in his uniform, but then says she likes him best in his evening suit with straw hat – the very outfit the audience has previously seen Niki wearing while visiting Franzi. She agrees, but then adds, ‘If you think he’s handsome in that, wait till you see him in –’ before breaking off. Franzi’s relationship with Niki has been sexual, while he has yet to consummate his marriage. This risqué scene, by devoting its imagery to clothes, can tap into what lies underneath them when it wants to, suggesting the naked sexual body under the concealing layers.

Franzi breaks away from this tricky subject by noticing her hostesses’ piano, and goes over to look at the sheet music arranged on the top. The titles of the pieces Anna is accustomed to play give further proof of her innocence and inexperience: ‘Cloister bells’, ‘A Maiden’s Prayer’. In a seemingly bizarre non sequitur, which sets up the theme of the imminent musical number, Franzi at once demands: ‘Let me see your underwear!’ When Anna hesitantly lifts her dress hem to reveal knee-length embroidered bloomers, the case of her own popularity and Anna’s neglect by Niki is solved for Franzi; after revealing the filmy silk scanties she herself is wearing, she sits down at the piano and begins to sing, ‘Jazz up your lingerie!’

Franzi’s song links jazz with colour, tactility and decoration in undergarments; her metaphor, suggesting that they both ‘wear music’ as their undergarments, works a parallel between Anna’s starchy cotton bloomers, her staid classical music and Niki’s lack of interest in her, versus her own satin undies, fast modern music and sexual experience. While Franzi exhorts Anna to ‘be happy, choose snappy/Music to wear’, the other woman supplies the occasional line to make the song a hesitant duet; but this ceases as the number continues and becomes the transformation scene. As Franzi sings and plays, Anna moves from sitting beside her at the piano to the middle of the room where she performs a few jazzy arm gestures. This image dissolves to one of a basket, into which then falls a mass of blonde hair – the transformation has begun. A cut takes the camera to the fireplace, and a fire onto which the offending cotton bloomers are placed. A large nightgown on the bed dissolves into scanty lace alternatives. Then another cut to the shoe closet reveals six pairs of button and lace-up boots: by a dissolve these resolve themselves into more fashionable shoes. This pattern is repeated in another cut to the wardrobe; four long-sleeved wide-waisted dresses dissolve to reveal sleek, sparkly and fur-trimmed replacements, slender and sleeveless. Throughout the scene the changes, but not their agents, are shown.

When the song and the scene ends, the two women leave Anna’s palace bedroom. Significantly, both are transformed. Franzi no longer sports the floaty, décolleté dress she entered the palace wearing; she now is dressed in a skirt and jacket, with black hat and gloves; she seems to have shed her glamorous and romantic appearance and to be coded much more as ‘career woman’. Since this transformation scene marks her handover of Niki to Anna, it can be seen that all Franzi has left is indeed her career, so this choice of outfit is appropriate.

Anna has changed more radically, however. Gone is her staid hairstyle of neat centre parting and plaits wound round her ears; instead her head is crowned by a smart modern permanent. Her dress style has changed too from a shapeless tube tied under the bust, to a gown cut on the bias, with spangled asymmetrical bodice and layers of ruched tulle below. The two women have not swapped places, exchanging dowdiness and sophistication; instead, while Anna has taken Franzi’s place, dress-style and man, the career woman has stepped out of the romantic position and dress style, as she now steps out of the film.

What is significant about this transformation is what it renders invisible. Other films, as explored, chose not to show the work required to turn each ‘good’ girl into a ‘bad’ one, as with Sandy in Grease, for example, or Madame Satan, in order to maintain suspense and surprise for both characters and audience. Here, however, the emphasis is placed differently. What is elided by the invisibility of the transformation is both time and labour – the labour of others. To make Anna into the new jazz baby who will attract Niki, the work of several servants and professionals must be necessary. Someone must cut and ‘marcel’ her hair; someone must burn the offensively maidenly knickers; someone else go out to buy the replacement shoes and gowns or bring in samples of likely outfits from suitable shops.

The magical nature of this transformation is played down by the matter of fact revelation of the two metamorphosed women opening the door and stepping into the corridor. The dissolves and cuts have elided the time and amount of help necessary to render them into their new incarnations – career woman and fiery jazz baby – and in later scenes it also seems that Franzi has taken the time to teach Anna jazz piano. The ease and rapidity of these fundamental changes are accomplished without fuss but with wealth. Presumably this is why the Hollywood film is set in the world of European royalty; this fantasy world is one in which radical transformation can be wrought through the magic that is money. Employing a make-believe country and its princess as one of its heroines allows the film to step outside real life into a fantasy zone. Strikingly, the shopping montage, as found in and as so many transformation scenes, manages to co-opt the same fantasy of effortless alteration for stories set in modern urban society, in ‘real life’.

In both the shopping sequence and its invisible twin, the emphasis is on the acquisition of new clothes and accessories as the sole labour needed to render the woman metamorphosed into a more glorious version of herself. Significantly, as has been noted in previous sections, the confirmation that the woman has successfully accomplished the transformation is inevitably found in male approbation: in The Cookie Carnival, the made-over gingerbread girl is crowned queen by a panel of male judges; in Grease, Sandy is hailed by not only Danny but his friends and other assorted males with whistles and astonishment, and in both Why Change Your Wife? and The Smiling Lieutenant the two newly sexualised wives both manage at last to secure the amorous attentions of their husbands. As will be considered in the following section, however, the ultimate proof of success in the act of self-revision is the occasion that sometimes comes before male approval – the instant where the woman is simply not seen because she is so different.

4) The Misrecognition Moment

This misrecognition moment is a recurrent trope in the context of the transformation. As noted above, it acts as the definitive evidence that the metamorphosis has been a success by implying that the alteration is so radical, the person revised is not recognisably her anymore. While rarer than some of the other tropes examined here, the misrecognition does appear often enough to merit exploration, especially as it features in two of the films which will be the focus of the case studies.

The misrecognition moment is also one of the most homogenous tropes; when found, it tends to play out in exactly the same visual and thematic terms each time. For example, returning to the moment at the end of Grease when Sandy appears metamorphosed from rigid maiden into willing vixen, there is a clear if brief instance of the misrecognition trope. Danny’s friends see Sandy’s alteration and gape at it before he himself notices; even then, before we see his reaction, we have a reverse cut to the object of all the visual and oral attention, as Sandy’s legs in her tight black trousers and high-heeled red shoes strut into the scene. The cut back to Danny shows him glance in the direction of his friends’ gaze, and then briefly away. He has seen the woman but simultaneously not seen her: he does not know who she is. Sandy’s alteration is so extreme, from the prudish Sandra Dee character in her pastel sweetheart-line dresses (with all this outline, as Turim (1984) has explained, connotes about her sexual innocence), to the raunchy high school femme fatale showing off her dangerous curves, that Danny does not at once realise it is the same person. Examination of his face shows a clearly distinct if rapid progression between non-recognition, doubt and dawning comprehension, as the miracle of his fantasy’s fulfilment is made plain.

Pretty Woman contains another similar scene, where the man’s incomprehension of the identity of the woman before him acts to confirm her success in transforming. As we will explore, notions of identity and of internal and external are intimately intertwined with the transformation metaphor; here, the woman’s apparent other identity actually confirms the fulfilment of the potential always inherent in her own identity but never before attained. Vivian (Julia Roberts), a prostitute on the streets of Los Angeles, has been purchased as a companion for the week by millionaire Edward (Richard Gere) in order to accompany him to various dinners and social events. Obviously, her hooker garb will not be appropriate wear for these occasions, so he empowers her to go shopping with his credit card. Edward has agreed to meet Vivian in the bar of his hotel; entering, he looks around, sees the woman but again does not see that it is her. The scene reinforces the significance of the moment for both of them through its choreography, revealed through deep focus: in the background Vivian sits at the bar with her back to the room, while Edward is seen in the near-ground looking around for her. Before he realises the well-dressed and elegant woman at the bar is indeed her, she turns her head, perhaps sensing his stare. He turns towards the camera and viewer; she turns simultaneously, producing a satisfying symmetry which gives the scene a pulse. Their relative viewpoints shift, from him looking unknowingly at the back of her head, to her looking at the back of his. We have seen neither of their faces; now the film returns them both to us and gives us the first view of Vivian transformed into a lady in her cocktail dress. The camera set up then changes, becoming placed between them for Edward’s reaction shots, as he realises who the elegant woman must be: he turns back to her, narrows his eyes as if both appraising and doubting his vision.

An even more pronounced instance of the misrecognition moment occurs in Silk Stockings: after Ninotchka’s autoerotic ballet with her new consumer durables, she comes down in the lift to the foyer of the hotel where her lover, Steve (Fred Astaire), is waiting for her. He is seen leaning against the front desk indolently; as Ninotchka steps out of the lift to the collective astonishment of the other men in the lobby, he continues to stare off into space. Even when Ninotchka approaches him directly he gives her only a rather dismissive glance and then looks away, as if being importuned by another beautiful woman. But then he ‘gets it’ and looks back with a start and a wide-armed gesture of amazement, ‘Oh no, it can’t be!’

This misrecognition perhaps hints that it is the clothes and not the woman, or perhaps the messages and meanings that the clothes seem to bear, or the money she has obviously spent on the clothes, that the men in these misrecognition scenes are reading, since Ninotchka has not altered her hair and seemingly wears no makeup. It is not her face or hairstyle, but only her outfit which has changed from military, utilitarian and desexualised, to glamorous, ultra-feminine and sensual.

While, then, the misrecognition moment is one of the rarer tropes found recurring in the filmic transformation, it does occur with sufficient regularity to make it noticeable, and with a certain visual inevitability that renders it significant. As it also gestures towards ideas about identity and about authenticity of the self, concepts that circle round the idea of transformation, it justifies attention. The misrecognition moment relies on the man not witnessing the work that has been done to change the woman: were he to see the actual scenes of the transformation, he could no longer respond with his spontaneous act of misidentification. This accounts for the misrecognition moment accompanying the invisible transformation, as with Grease, Madame Satan, Pretty Woman and Silk Stockings. Although Pretty Woman shows the audience the shopping montage that stands in for, and acts as, Vivian’s metamorphosis, and the other films provide narrative hints that self-revision will be attempted, the man who is the occasion for the transformation must not be allowed to observe it.

Many of the tropes utilised to tell the Hollywood transformation story are, as noted, bound up with ideas about identity and authenticity. With the next trope examined, however, the intimate connection between external and internal, and their effects on each other, is fiercely disavowed: profoundly involved with ideas of disguise, concealment and deceit, the false transformation acts to reinforce the habitual association of appearance and character by providing specific circumstances in which these associations are undermined.

5) The False Transformation

Madam Satan is a useful place to begin the examination of the false transformation trope, since its basic plot-lines and events have already been reviewed. The false transformation operates when the central protagonist appears to have undergone a radical metamorphosis, but this is in fact not so: the change is only feigned, the new persona a masquerade.

Angela differs from the wronged wives in Why Change Your Wife? and The Smiling Lieutenant because, unlike them, her change of costume, although as extreme as theirs, is not meant to be symbolic of an equivalent personality alteration. While all three films set up very stark binary oppositions between prim and willing, prudish and frank, sensuous and ascetic, with the women first on the more staid side of the dichotomy, crossing over to the other more liberal side after their transformatory outfit is donned, Angela, unlike Beth and Anna, has not really been altered so easily. The film takes great pains to show that her performance as Madam Satan is just that, a performance, and one that is also not entirely tasteful to her. Angela has been driven to seeming, rather than becoming, her contrary, whereas Beth and Anna enthusiastically embrace their polar opposites. Angela’s masquerade is adopted first in rage, to oppose the showgirl who has stolen her husband, but then it is used in the hope of convincing Bob that he really does prefer the modest, more passive type of woman, like his wife.

Madam Satan ends as the other two films also do, with the married couple happily re-established, but Angela’s work to achieve her happy ending is more difficult than the other women’s. She has not changed, bringing herself into line with her husband’s desires for a more sexually responsive partner; moreover, Bob feels she has humiliated him through her pretence. Angela’s agency has been turned to pretence, to masquerading as another woman, rather than, more acceptably, becoming one through costume, styling and shopping.

Phantom Lady (1944) seems to grant a good narrative excuse to its heroine, Carol ‘Kansas’ Richman, for her masquerade; she undertakes it in order to save the life of her boss (whom she loves), when he is accused of murdering his wife and sentenced to death. Carol believes in his innocence, and sets out to prove it. One attempt at finding evidence necessitates vamping a low-life jazz drummer, Cliff Milburn (Elisha Cook Jr) who also plays in a theatre orchestra. Carol entices him to reveal his knowledge of the real murderer, but significantly does not do so in her proper person. She transforms herself, becoming the kind of girl that would tempt Cliff: Jeannie, a ‘hep kitten’. A cut between scenes effects Carol’s change from smart-suited secretary to cheap date; the camera finds her sitting in the theatre audience giving Cliff the eye. But Jeannie herself is twice the object of the camera’s pan-up of approval. The second look reproduces Cliff’s as he eyes up the woman flirting with him, but the first is linked to the camera and thus the viewer alone. This sweep up her body, dwelling on her legs in fishnets, her tight satin dress, overly made-up face and excessive junky jewellery, underlines the extremity of the transformation from good girl to bad: without this intense stare at the woman we might not recognise in her the plucky heroine. This look of non-recognition is repeated in the next scene when Carol/Jeannie goes to a jam session with Cliff; he kisses her and she retreats to a mirror to reapply her lipstick. The look of misrecognition she gives is then at herself, what she has become because of this masquerade; Carol shakes her head in revulsion at the depths to which she is prepared to sink in order to save her man.

The film too seems worried about the excessive charge of Jeannie’s sexuality and does not dwell on how the prim Carol amassed the cheap items she needs for her masquerade as the evidently lower-class, sexually experienced woman. Thus even given the best of motives for their protagonists, Hollywood films find the false transformation worrisome and often punish the woman who indulges in them; Carol is menaced and eventually attacked by the real murderer.

This tacit disapproval for the woman who merely appears to change is often found accompanying the false transformation; in Madam Satan, although she does win Bob back, Angela has to work hard to do so and to dissipate the negative charge carried in the narrative for her as a woman who uses active powers not to change herself but to attempt to change her husband. In The Major and the Minor, Susan Applegate’s masquerade as her own younger self, Su-Su, is sanctioned generically as she is in a comedy and narratively because she is a nice girl trying to flee the many male wolves in New York City; even so, although her disguise allows her successfully to ride the train for the wrong fare, it prevents her from getting what she then comes to want, a romantic relationship with Major Philip Kirby (Ray Milland), and she suffers many comic embarrassments until she gives up the deception.

The taint of deceitfulness that surrounds the alteration of the exterior when it is not matched by a similar change to the interior person explains why the false transformation is often found given a negative portrayal, especially in narratives from darker genres like the thriller or noir. The notion of the metamorphosis being not merely a disguise but also temporary inheres in this trope, further unsettling the connection between exterior and interior.