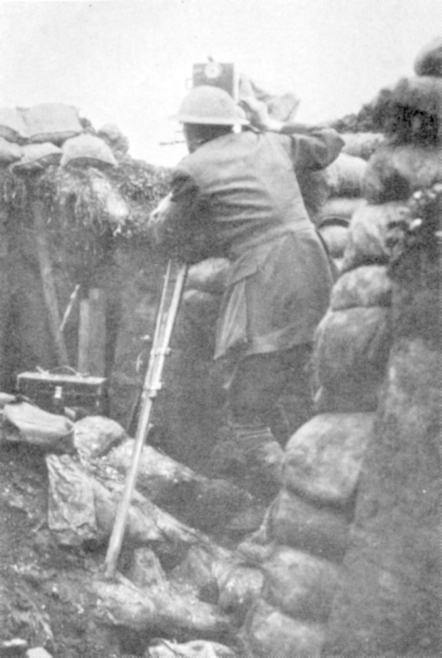

Malins using a Debrie camera with the characteristic rear-mounted film counter. This photograph is the frontispiece to his book and is captioned as having been taken on the Somme. (Malins)

Any analysis of the work of McDowell and Malins involves an understanding of the technical capabilities and limitations of the equipment that they were using.1 The capture and projection of moving images became a practical technology from the 1890s onwards. Cinematography grew from advances in still photography. Both work by allowing light to fall on to a flat surface treated with a light-sensitive substance. The resultant chemical reaction becomes visible by immersion in a bath of chemicals (developing) and is then made permanent (fixing). Because of the limitations of the early light-sensitive chemicals, called emulsions, exposure times were measured in minutes. By the late 1880s gelatine bromide emulsions reduced this to a fraction of a second. Film manufacturers were also able to produce a transparent, flexible and robust base made of celluloid which could be coated with the new emulsions and would stand the stresses of the exposure process. When perforated with sprocket holes strips of celluloid film could be drawn swiftly past a lens, each opening of the shutter recording a slightly different image as the film stopped briefly in front of it. After processing, the picture on the exposed film was visible in negative. Any unwanted footage was cut out and the film spliced into the required order before being printed on to another reel of film resulting in a set of positive images. Projection has to replicate the same intermittent motion and the same running speed as was used during exposure. The positive film, when passed frame by frame in front of a strong light source and projected on to a surface, created the illusion of movement.

The film in use in 1916 was made from cellulose nitrate, a derivative of wood pulp. Nitrate film is strong and relatively cheap to produce but has two major faults; being chemically similar to gun cotton, it is highly inflammable and cannot be extinguished even by immersion in water. The other characteristic is that it decomposes and eventually becomes unusable. The fumes released during this process can cause spontaneous combustion, making the storage of early film difficult. This only became clear in the 1940s when some stock was already half a century old. The phenomenon was of little interest to the cinema industry in 1916, which was generally intent only on maximising the profit from its productions. Heavily used prints often became badly damaged only months after issue and many were scrapped to recover the silver content in the emulsion. By the latter half of the twentieth century much surviving early film had decayed or was too volatile to keep. Despite the success of The Battle of the Somme, there is only one group of copies in existence that can confidently be linked directly back to the original. These all derive from a negative, believed to have been the original, reassembled in 1917 after some of it had been used in other films and transferred to the Imperial War Museum. The Museum possessed two other copies, including one on 1916 dated stock that may have been the original release, but these were destroyed when they became unstable during the 1950s or 1960s.2

The cameramen used 35mm orthochromatic film which is sensitive to the blue and green areas of the spectrum. While it was an improvement on earlier emulsions which only registered blue light, it was not as effective as panchromatic film which also recorded the red areas. Panchromatic film was produced before the Great War but required total darkness in the handling and developing processes, unlike ‘ortho’ film which could be worked on in red light as it was not sensitive to that wavelength. However, some elements of a picture, especially those in the red area of the spectrum, did not register very effectively on orthochromatic film. Particularly noticeable is the lack of detail in the sky: clouds did not photograph well. The contrast between light and dark areas of the image tends to be stark and there is little graduation of tone in shadows. Events were often fast moving and difficult to follow, the angle of the lens was fairly small, cameras were bulky, light could change or fade, and mechanical failures could occur. Focusing was normally set up before shooting and exposure was regulated by altering the shutter blade so that more or less light was admitted when the shutter opened. Most cameras had no view finder and keeping the subject in shot was a matter of experience and skill. The filming of combat included all these problems, with the addition of mortal danger. Comparison of the efforts of Ashmead Bartlett and Brooks in the Dardanelles as seen in their film Heroes of Gallipoli with those of Malins and McDowell on the Somme gives a clear impression of the difference a skilled cameraman could make. Ashmead Bartlett could not even do a pan without making the camera shake in some cases! Assuming a safe camera position with a good field of vision, there was often not a lot to see. Smoke and shell bursts were commonplace but difficult to film. Ironically the development of moving pictures coincided with the arrival of the ‘empty battlefield’. Thus when filmed from any distance, attacking troops were no more than dots and defending troops were almost always invisible. Telephoto lenses were used in the Boer War but there is no evidence that Malins or McDowell had them.

Film was supplied in circular tin cans and was transferred to the film magazine using a changing bag. The film and the magazine were put into the lightproof, fabric bag and the operator removed the film from its tin and wound it on to the spool in the magazine entirely by feel. Exposed film was removed from the magazine and replaced in the tin by the same method; nicks or holes were often made in the film with scissors or a film punch to indicate the end of shots. The logistics of McDowell and Malins' operation are unclear. The normal procedure during newsreel filming was for exposed film to be sent back shortly after it had been taken so that the cameramen would get feedback on whether it had come out and what shots still needed to be filmed. Such evidence as there is seems to indicate that the film was sent back in one consignment on or about 10 July. In an interview given on that date McDowell certainly did not know if his 1 July footage had come out, something he would surely have been aware of if the film had been returned to London in batches.3

Malins using a Debrie camera with the characteristic rear-mounted film counter. This photograph is the frontispiece to his book and is captioned as having been taken on the Somme. (Malins)

Malins began his film career in the Great War using an Aeroscope camera. This was a relatively light and portable design powered by compressed air but there were doubts about its reliability, although Bertram Brooks Carrington believed that it was fine if looked after carefully. Malins may have used a Debrie camera, a French design, for some of his filming on the Somme, while McDowell used the larger British Moy and Bastie, described below. Photographs taken by Ernest Brooks at White City and La Boisselle show Malins also using what looks like a Moy and Bastie rather than the smaller Debrie. Both types were hand cranked and, unlike the Aeroscope, needed a tripod which hindered mobility. It seems that when Malins went to Advanced GHQ on 2 July he picked up his Aeroscope with the intention of using both cameras but near La Boisselle he lost the assistant who was carrying the Aeroscope and he probably continued using the Moy and Bastie.

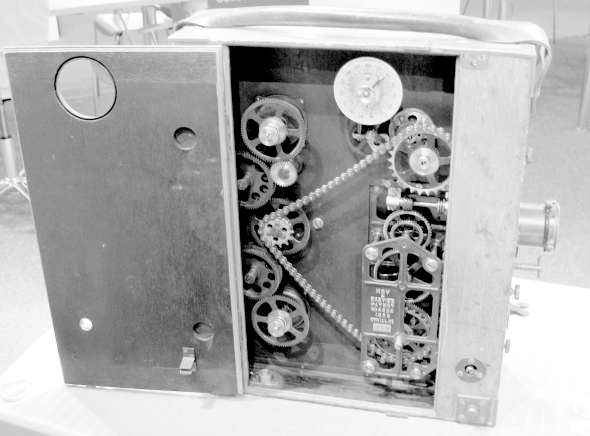

The Moy and Bastie was a standard ‘upright’ camera consisting of a rectangular mahogany box subdivided along its long axis into two light-proof compartments, accessible by doors on each side. The door on the left side gave access to the film magazines and the lens mechanism. The right-hand compartment contained the drives for the film, the shutter and the intermittent mechanism. The cameraman carried several pre-loaded magazines of up to 400 feet which provided over six minutes of film; a magazine change could be carried out in a minute or so by an experienced cameraman and film consumption was monitored by a counter. Power to operate the camera mechanism was supplied by the hand crank which drove a chain and a series of cogs. Standard 35mm film was designed to be exposed at 16 frames per second. As one revolution of the crank moved eight frames the cameraman had to complete two revolutions per second, although slightly faster or slower speeds were sometimes used depending on the light. Brooks Carrington said ‘hand cranking came naturally. Purely automatic even under shellfire.’4

A Moy and Bastie camera at the National Media Museum.

‘Mac’ McDowell with a Moy and Bastie ciné camera. This photograph appeared in Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly on 13 July 1916 and therefore represents his appearance on the Somme. He is dressed as an officer without rank or regimental badges. The ‘head’ mechanism which traversed and elevated the camera can be seen on the tripod. Using the left hand for the movement while maintaining a steady two revolutions per second with the right hand was not as difficult as it seemed and came with practice. (Kevin Brownlow)

Photographs exist from earlier in 1916 showing Malins using a Parvo camera which was first manufactured in 1908 by Joseph Jules Debrie. This was a rectangular wooden box built round a metal frame which ran from front to rear, on which were mounted the mechanisms and film magazines. The sides had rearward opening doors and the front panel hinged upwards for access, and although the basic principle was similar to the Moy and Bastie it had some extras, including a film counter on the back rather than the side, a spirit level for accurate placement of the tripod and a revolution counter which could be set to either 16 or 24 revolutions per second to assist with exposing the film at a constant speed.