The 7 Division attack on 1 July taken by a cameraman of 1 Printing Company, Royal Engineers. (IWM Q89)

John Benjamin McDowell has always been overshadowed by Geoffrey Malins in the story of filming the Battle of the Somme. He left virtually no record apart from interviews which he gave to Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly on 10 July and to Screen on 7 October 1916. He apparently took no part in the editing of the footage and some material that he expected to see in the finished film did not appear. A common interpretation is that Malins alone was responsible for editing the film and is alleged to have deliberately selected his own footage at McDowell's expense. There is no explicit evidence that this is the case and equally no doubt that Charles Urban was in fact the editor. Urban may have had help from Malins but we suggest that he was quite capable of seeing through an attempt to favour one cameraman over another and would have judged the shots on their merits, regardless of who took them.

The best estimate is that the two cameramen shot about 4,000 feet each. Nicholas Hiley believes that ‘the IWM print suggests that the final version of the film included only 25 per cent of the material McDowell took but a massive 82 per cent of the footage shot by Malins’. On the face of it this does support the case for Malins having favoured his own material but we believe that the balance is more even than Hiley indicates. We cannot confidently assign every single shot to one or other cameraman but each has about the same amount of footage in the film, based upon our analysis of the time and place of each shot, rather than taking the attributions from the dope sheet. If there is an imbalance this is as likely to be due to poor image quality, inaccurate record-keeping or mechanical failure as to deliberate manipulation.1

The first interview on Monday 10 July gives some insight into McDowell's working methods. He said:

I was under fire several times on the first day of the Big Push, and I am hopeful that I have secured a number of interesting pictures. No, the big gun fire and the concussion did not upset me, or interfere with my ‘taking’ as much as I had anticipated it might do. But I think this might have been due to the fact that years ago I was engaged on the proving of guns and ammunition at Woolwich Arsenal, and so became more or less familiarised with the reports of big gun fire.

In all, I have secured about 4,000 feet of negative, and some of the pictures, which, by the way, I am particularly anxious to see on the screen, should prove most interesting. I got a number of views in our front-line fire trenches – which were only 150 or 200 yards from the German line – and you can see our shells bursting. On the first day of the great offensive I secured pictures of the bombardment, of the prisoners coming in, wounded arriving, and a good general view of our troops in the open with the German shells bursting over them. The latter view naturally is in the distance, and I am curious to see how it turns out.2

Some of the shots he describes are clearly identifiable and are discussed below but there is no footage of troops advancing as he describes. Possibly the film was not sufficiently good to be included. There is one clue in a still photograph taken from the British front line at about the same place as shots 12.3–8. This is believed to have been taken by a cameraman from 1 Printing Company, Royal Engineers on 1 July although we have been unable to discover his identity or indeed if there was more than one. It does give an idea of what McDowell's footage might have looked like and may have been taken at the same time. The distant troops are possibly 1 South Staffordshire Regiment or 22 Manchesters from 91 Brigade, 7 Division.

There is contradictory evidence as to when McDowell departed for France. The Times states that he left on 28 June while Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly reported that ‘he had less than forty-eight hours in which to make the necessary arrangements before he left for France, and four days after his arrival “The Big Push” began’.3 Brooks Wilkinson asserted that he set out ‘within a few hours after leaving the meeting’. He would have acquired a camera, a supply of film and a uniform before leaving. He presumably did not know the date on which the offensive was due to start so he had the additional concern of trying to get there before it was launched. McDowell remembered:

The 7 Division attack on 1 July taken by a cameraman of 1 Printing Company, Royal Engineers. (IWM Q89)

I would not have missed it for anything. At the same time I've seen a good deal I'm never likely to forget. Things move so rapidly at the front, however, that one's first impressions soon become blurred. Strange to say, I was more worried and nervous during my journey from Charing Cross to Dover about the success of the pictures I hoped to take, than ever I was in the trenches with the German bullets whizzing overhead.4

McDowell described the difficulties of filming: ‘I walked through miles and miles of trenches, and you may guess it was no easy job getting along with a heavy camera and tripod, often through deep mud and slush. On the day after the great advance we “borrowed” a German prisoner and he carried the camera for us, which made things a bit easier.’ In his October interview he elaborated:

Naturally from the firing line back five miles the land is alive with shell-bursts and a cinematograph operator's life there, getting to the front with his apparatus, is not enviable. The camera weighs about forty lbs to begin with, but after carrying it along roads and over broken country with the ‘crumps’ going off casually and then along the trenches for hours, it seems to weigh about four hundredweight. We start out under the guidance of a captain whose name deserves to be better known and no doubt will be some day, and our car takes us as near the scene as it is considered safe for a car. Then we get out and look for trouble. One gets smothered with dirt thrown up by bursting shells. It even gets into the mouth.

McDowell and his camera in the trenches. The small box respirator worn by the man on the left dates the photo to after July 1916. (Kevin Brownlow)

Sadly we have no clues as to the identity of his conducting officer. McDowell's experience gave him a great respect for the resilience and humour of the British Tommy: ‘It never ceases to astonish you. The more you see of them the more you wonder at them and admire them. They make grim jests at fate. Nothing daunts them.’5

We give below the shots taken by McDowell before 1 July but as we have little information on his movements we cannot be sure if the order is entirely accurate.

Date: 27–29 June 1916? Place: probably around Meaulte. Interior and exterior of a covered gun position containing a 60-pounder gun. Shots: 13.1–3. Stills: DH39, IWM FLM 1651. Cameraman: McDowell?

The dope sheet gives the date of this shot as 27 June and the place as ‘Albert Road’ – a very unhelpful description. Shot 4 of this caption was filmed near the Sucrerie facing Beaumont Hamel and is discussed in chapter 4. The significant clue to the first three shots is the mention of a Canadian battery. Only three Canadian batteries that served on the Somme in June 1916 have been traced and the best candidate is 1 Canadian Heavy Battery which used 60-pounders from February 1915. The Corps boundary with III Corps ran from the Ancre just north of Meaulte to Bécourt. No detailed maps of battery positions in this area are known and there is little in the footage to suggest a location. Unfortunately the battery war diary gives no map reference for its position before 1 July. The attribution to Malins is doubtful as this is a long distance from the area in which he took all his footage. If the battery is indeed Canadian, this footage may have been taken by McDowell although it is not certain that he had arrived in France on 27 June so the date would be incorrect. The suggested location around Meaulte or even further south would certainly favour McDowell.6

28 June 1916? Place: north of Bray-sur-Somme. Description: French women working in a field. Shot: 7.1. Still: DH20. Cameraman: McDowell.

This shot is attributed by the dope sheet to Malins near Albert but was actually filmed from west of the D147 road from Bray-sur-Somme to Fricourt.

Date: 29 June 1916? Place: railway line south of Bécordel. Description: 6-inch howitzers firing on Mametz. Shots: 12.1–2. Stills: DH32, DH35. Cameraman: McDowell.

The scene is shot from the railway embankment running towards Bécordel. It consists of a pan of a single howitzer, followed by a static shot of four howitzers firing. The Willow stream can be seen in the background as can the ruined village of Bécordel.

The gun position is well constructed with earth side walls reinforced with timber. There is a burster layer of sandbags laid on corrugated iron sheeting. Although more elaborate than other gun pits seen in the film the position seems genuine; the layout conforms to plans of covered positions for the 60-pounder.

A tent with a red cross on it can be seen in the distance, presumably part of an ADS or MDS. The site of Bray Hill cemetery is visible in this shot but it was only established in 1918. (DH20)

The access road from the D938 runs down the hill and takes a left turn before crossing the Willow stream. To the right of the road is a stand of trees concealing a section of the embankment of the old metre-gauge railway line from Albert to Peronne, on which McDowell placed his camera. The dope sheet seems to allocate these shots to 29 June, which would fit with McDowell's arrival in the area. No location or cameraman is given.

The guns in this sequence are 6-inch 30cwt breech-loading howitzers, from one of three batteries allocated to XV Corps before 1 July. The appendices to the XV Corps artillery war diaries are missing and it is impossible to identify the individual battery. The 30cwt howitzer was obsolescent by 1914 and was not an entirely successful design, being very short-ranged for its size. From 1915 onwards it was replaced by the 6-inch 26cwt howitzer which could fire twice as far. It is very surprising that the gun position has no protection at all. The shells are piled up next to the pieces which are entirely out in the open with no concern for German counter-battery fire. The bagged charges seem to be stored in the lee of the railway embankment or perhaps in a brick-lined culvert that still exists.7

The railway embankment runs towards Bécordel village and then takes a left turn before the stream. Only one 6-inch howitzer is visible in this shot. (DH32)

The tree growth on the old railway embankment makes an exact comparison shot impossible. The Willow Stream runs along the trees at the foot of the slope with the southern end of the village visible in the distance.

Date: 29 or 30 June 1916. Place: east of Mansel Copse. Description: the bombardment of Mametz. Shots: 12.3–8. Still: DH39. Cameraman: McDowell.

The six shots that follow the footage of the howitzers show shells landing on the German trenches in front of Mametz and on the village itself. The viewing notes cast doubt both on the location and the genuineness of the footage. The film was in fact taken from the British front line above the present-day coach parking bays in front of Mansel Copse.

This footage is of historical significance as it shows part of the terrain over which 2 Gordon Highlanders and 9 Devonshire Regiment passed on the morning of 1 July. It is very much the scene that Captain Duncan Martin of 9 Devonshire Regiment looked on with such trepidation. The story is well known and is recounted in Martin Middlebrook's The first day on the Somme as well as being mentioned in the British Official History. While on leave Martin constructed a plasticine model of the area and deduced that his men were vulnerable to fire from a German machine gun in the village cemetery. His prophecy came horribly true and he died with many of his men on the slope above Mansel Copse. He is buried in Devonshire Trench Cemetery.8

In shot 12.4 the Albert to Peronne road can be made out. The narrow gauge railway ran parallel to it on the north side. 2 Gordon Highlanders jumped off from the trenches in the film attacking along the valley towards the railway station.9

The position from which McDowell filmed the shelling of Mametz. The view is looking north-west towards the village on the horizon with the D938 in the foreground. McDowell filmed shots 37.1–3 from the bank in the middle distance. The German front line is just beyond the left-hand end of the bank.

The top two views show shells landing on the enemy's support line. Hidden in the smoke are the village cemetery and the shrine with the machine gun post. The third photograph shows the British front line and the fourth image is of the British support line with the German trenches beyond. (DH39)

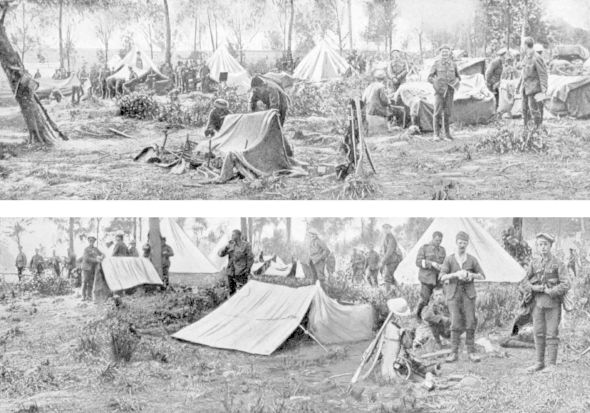

Date: 28–30 June 1916. Place: Bois des Tailles. Description: men of 2 Royal Warwickshire Regiment in bivouacs. Shots: 18.1–6. Stills: DH55, DH56, Q79488. Cameraman: McDowell.

Caption 18 is dated by the dope sheet to 29 June 1916, which adds that ‘this regiment moved off into the firing line the same evening’. The viewing notes suggest that the troops are 2 Royal Warwickshire Regiment of 22 Brigade, 7 Division. This battalion was in ‘tents and hutments’ in the Bois des Tailles between Morlancourt and Bray, having arrived there on 25 June. They were due to move on the evening of 28 June but the postponement of the attack delayed their departure until 10.50pm on 30 June. McDowell could have filmed them at any time between 28 and 30 June. If the caption is correct, the most likely date would be the evening of 30 June. A number of men appear in more than one shot, thus linking them all together, and it is quite possible that McDowell took them within minutes of each other.10

A panorama from Sir Douglas Haig's great push which has been stitched together from individual frames from the film for inclusion in the book. The man with the white armband in front of the bell tent on the right of the second photograph is also seen behind the bivouac with his hand to his mouth, apparently filling a pipe. In the film he walks from left to right and therefore appears twice. The man in the cardigan (second from left), wearing a cap comforter, appears in shot 18.3 walking across the screen from right to left, thus providing a link between shots 18.1 and 18.2–3. A number of the panorama sequences in the book were very skilfully assembled in this fashion although close examination shows some joins. (DH55)

The first shot comprises a long pan from left to right over the bivouac area showing an assortment of improvised shelters, some bell tents in the background, and men sitting about. One man, seen in the second photograph below, has a white band on his right lower sleeve which indicates he is a wire cutter according to the scheme of badges set out in 7 Division orders.11 The same man appears again in shots 18.5 and 18.6, thus proving the footage is of the same unit. No other battalions of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment served in XV Corps, which supports the identification of the men as being from the second battalion. The man on the far left of the pan is putting on his equipment which is the 1914 leather pattern, a type not normally issued to regular battalions. The wood was packed with troops and it is probable that he was from a different unit.

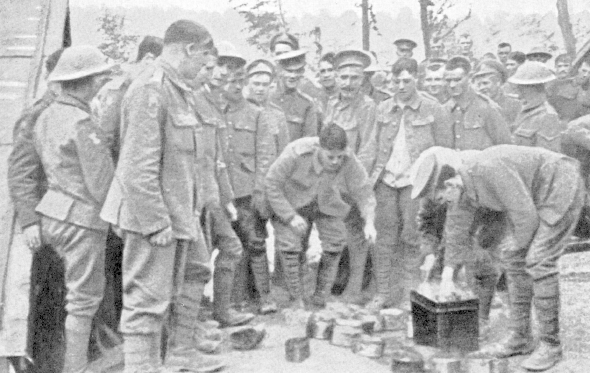

Shots 18.2 and 18.3 show the distribution of stew into mess tins. The scenes are framed by two temporary timber huts and the background of sparse woodland seems to fit with the previous shot. The presence of ‘a white grenade two and a half inches in length on right sleeve just below the shoulder’ confirms that the men are from 7 Division. It was worn by men detailed as bombers rather than those who had qualified for the trade badge.12

Shot 18.4 is unconnected. Taken in July 1916, it shows a group of men in goatskin jerkins. This footage is very similar to a scene in part 2 of The Battle of the Ancre and the Advance of the Tanks, which the dope sheet to that film dates to 4 November 1916.

Screen grab from shot 18.2 showing bomber's badges on the men on the left-hand side.

Shots 18.5 and 18.6 show a group of men eating round a fire. 18.5 is a long shot with a left pan while 18.6 shows the centre of the group. This photograph is a screen grab from shot 18.6. One man on the left has a Royal Warwickshire Regiment cap badge. The man to the right and behind the soldier with the steel helmet putting his spoon into his mess tin appears in shot 18.1. The viewing notes mention the peculiar hairstyle of two men on the right and one at the back with close-cropped hair and a long tuft at the front which is said to be ‘somewhat in vogue in the army of 1916’.13 (IWM Q79488)

Date: 30 June 1916. Place: Bray-sur-Somme. Description: 7 Buffs listening to orders; troops marching through Bray-sur-Somme. Shots: 6.1–3. Stills: DH20, Q79478. Cameraman: McDowell.

Bray-sur-Somme is about 5 miles south-east of Albert and had been a British billeting and headquarters area since the summer of 1915. Because it was near the boundary between the British and French armies it was often used also by French troops who can be seen in one shot. The dope sheet attributes this footage to Malins, but he was at White City on 30 June.

Shot 6.2 is of a column marching up the main street in Bray-sur-Somme. The men are wearing 1914 pattern equipment and are loaded with bandoliers and PH hoods. There is an illegible symbol on the helmet covers. In addition a flag and two heartshaped markers on short poles are being carried. The viewing notes offer 8 Suffolk Regiment, 18 Division as possible subjects, probably on the basis that their name appears in the caption and that the Buffs and Bedfords are accounted for in shots 6.1 and 6.3.

Shot 6.1 shows a parade in a side street in Bray-sur-Somme. The viewing notes identify the battalion as 7 Buffs (East Kent Regiment) of 18 Division on the basis of the letter ‘B’ visible on the officer's helmet cover and the fact that they are mentioned in the caption. It might equally well stand for ‘Bedfords’ who appear in shot 6.3 and have a device, possibly a letter ‘B’, on their helmet covers. Alternatively the letter may merely show the officer's company. The men wear helmet covers without any insignia on them and also 1908 pattern equipment which is unusual, although not impossible, for a New Army battalion. (DH20)

The same street in 2007.

Shot 6.3 shows D Company, 7 Bedfordshire Regiment, 18 Division. This identification is given in Martin Middlebrook's The first day on the Somme where the officer is named as Lieutenant Douglas Keep, although the origin of this information is not known. Comparison with a photograph of Keep shows that they are the same man. The battalion arrived in Bray from the trenches at 1am on the morning of 29 June and spent the day resting. They moved back up for the assault sometime during 30 June and were filmed by McDowell who had set up his camera in the main street.14

The equipment worn by the men conforms exactly to paragraph 20 of the battalion operations order issued on 30 June 1916, which lists ‘Equipment to be carried on the men. Every man will carry: – Rifle and equipment less pack. One bandolier in addition to his equipment ammunition (170 rounds in all). One day's ration and one iron ration. One waterproof sheet, two sandbags, one yellow patch on haversack on his back. Two smoke helmets. Grenadiers will only carry fifty rounds SAA.’ According to the 18 Division operations order of 23 June the yellow patch on the small pack was the divisional identification although no example appears in the film. 7 Bedfords was a New Army battalion and the men are wearing 1914 pattern equipment. The ‘smoke’ or PH helmets in their cases are slung one over each shoulder, while the waterproof sheet and the sandbags seem to be folded on top of the haversacks on the back; the cotton ammunition bandoliers can also be seen. They are not excessively loaded down although the orders state that 50 per cent of them would have to pick up additional tools at a dump nearer the front line.15

Douglas Scrivenor Howard Keep was born in Sydney, New South Wales on 17 June 1893, the second son of John Howard Keep and Agnes Rosa Keep. Douglas had an elder brother, Leslie, who also served in 7 Bedfords. The family must have returned to Britain as Douglas was educated at Leighton Park School in Reading and later went to Wadham College, Oxford, where he was a member of the Officer Training Corps for two years and rowed for his college. He enlisted in the Public Schools Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment on 11 September 1914 at St James Street, London, while simultaneously applying for a commission in the Bedfordshire Regiment. He and his brother Leslie were medically examined at the same time and both men stood six foot tall. Douglas was commissioned as a temporary second lieutenant in the Bedfordshire Regiment on 29 September 1914. Leslie Keep served in the same battalion and survived the war. Promoted to lieutenant in the spring of 1915, Douglas went overseas with 7 Bedfords on 26 July 1915.

On 1 July D Company was in support of the two assaulting companies and suffered a number of officer casualties although Keep escaped unscathed. The battalion was involved in the assault on Thiepval village in September and he was awarded the MC for his part. He was promoted to acting captain with effect from 28 October 1916. On 15 July 1917, at the age of 24, he was killed by a shell while supervising a working party near the banks of Zillebeeke Lake south of Ypres. He was buried at Reningholst New Military Cemetery.16

A grab of a platoon of D Company, 7 Bedfordshire Regiment marching north out of Bray-sur-Somme on 30 June 1916 with Lieutenant Douglas Keep at their head. (IWM Q79478)

The same street in 2007.

A photograph of Douglas Keep taken from War Illustrated, 18 August 1917.

Date: 30 June 1916? Place: Bray-sur-Somme or Morlancourt? Description: column of troops marching right to left past camera. Shots: 6.4–5. Stills: DH21, Q79479–79481. Cameraman: McDowell.

The final two shots of caption 6 offer a fascinating glimpse of a British Army battalion on the march, showing rifle companies, Lewis gun sections and transport. Unfortunately we have been unable to identify either the battalion or the place. The dope sheet attributes the whole of caption 6 to Malins. The other shots in the caption were undoubtedly taken in Bray-sur-Somme and can be dated fairly securely to 30 June 1916, a time at which McDowell was in the area. There is no certainty that this material has any relationship with the previous scenes. A search of Bray-sur-Somme failed to produce anywhere that resembled the scenery in the shot and we would welcome any suggestions.

The viewing notes suggest that the men are from 1 Royal Welsh Fusiliers, on the basis that the Buffs, Bedfords and Suffolks are seen in the other shots. However, the entire battalion is wearing 1914 pattern equipment, which was almost exclusively issued to New Army battalions and would not have been worn by a regular battalion. The troops are wearing steel helmets but there are a few in service caps; the cap badges, although not clear enough to identify, do not resemble those of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers.

The unidentified battalion on the march headed by Lewis gunners with their carts and a man leading the company commander's horse. The 1914 pattern leather equipment is clearly visible on the men behind. (IWM Q79479–79480)

Date: 28 June 1916. Place: Bois des Tailles. Description: Manchesters' church parade. Shot: 14.4. Stills: DH44, Q79485. Cameraman: McDowell.

The shot comprises a left pan over a church parade with a hillside in the background. The viewing notes point out that a sergeant at the end of the shot has the crossed pick and rifle of a pioneer battalion on his collar and suggests that the men are from 24 Manchester Regiment, the pioneer battalion of 7 Division. Other men appear to be wearing collar dogs but they are not readable. The dope sheet gives the date of 28 June which probably means that McDowell filmed this shot shortly after his arrival and that it may have been taken around the Bois des Tailles, which is where the 24 Manchesters and 2 Royal Warwickshires were located on that day. There is no mention of a church parade in the 24 Manchesters war diary but the men were resting on 28 June so might have been able to attend one. McDowell remembered ‘I was present, and got a picture of an open air church service, attended by the troops before going into action’, which confirms the dope sheet attribution to him.17

Date: 28–30 June 1916. Place: not located. Description: a battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment marching along a road. Shot: 21.1. Stills: DH57, DH58, IWM FLM 1658. Cameraman: McDowell.

This shot shows a battalion on the march along a road with a barn-like building in the distance. The dope sheet gives McDowell as the cameraman and states that it was shot ‘near Albert’ on 29 June. The viewing notes provide the additional location of the ‘Bécourt–Bécordel road’, although it is not certain where this information comes from. The terrain in the film does not match that between Bécourt and Bécordel and the actual location is probably some distance away from the trenches. The viewing notes suggest the battalion is 2 Royal Warwickshire Regiment but, like the column seen at Bray in shot 6.3, these men wear 1914 pattern equipment and are therefore unlikely to be regulars. None of the men seen in caption 18, which we can securely identify as 2 Royal Warwickshire Regiment, is wearing shorts. A photograph on p. 58 of Sir Douglas Haig's great push is captioned ‘a new battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment resting on their way to the trenches’ and shows men in shorts sitting beside the road. This is a grab from missing film which is still extant in a compilation entitled The Holmes Lecture Film (IWM Film and Video Archive 468/2). Nothing is known of Holmes but the five reels were put together from The Battle of the Somme and other films sometime after 1918. A grab from the existing footage is on p. 57 and states that ‘reserves were being marched up to the reserve trenches over the greater part of the British lines previous to July 1’. Unless the dope sheet is wrong in every respect and the men shown are from 48 Division, which had several battalions of Warwickshires, we suggest that the film shows men of the 10 Royal Warwickshire Regiment, who spent the days preceding 1 July in the Morlancourt area in III Corps reserve and at least are ‘new’ and ‘reserves’.18

Church parade in the valley of the Bois des Tailles. (IWM Q79485)

A shot showing part of the battalion on the march. Note the shorts and the badges on the front of the helmets. (DH58)

The screen grab of the excised footage. (DH57)

Date: 28–30 June 1916. Place: Minden Post? Description: Royal Artilleryman holding fox cub. Shot: 7.6. Still: DH24. Cameraman: McDowell.

The dope sheet gives the date of this shot as between 25 and 30 June 1916, although it is probably nearer the latter. The scene is credited, probably correctly, to McDowell. The gunner holds a very tame fox cub. Soldiers of the Royal Artillery, RAMC and Queen's Regiment can be seen. 2 Queen's Regiment was part of 91 Brigade, 7 Division. The dugouts visible in the background may be part of the shelters constructed in the south side of the road embankment at Minden Post. McDowell took about six and a half minutes of film in this location but there is not enough detail to make a conclusive identification.

We have no indication of where McDowell spent the night of 30 June 1916 but his filming on 1 July and after is described in Chapter 8.