FIGURE 1: Margaret (left) and June Murray (right) reading photographs to relatives at Erambie, 2011.

PICTURE WHO WE ARE: REPRESENTATIONS OF IDENTITY AND THE APPROPRIATION OF PHOTOGRAPHS INTO A WIRADJURI ORAL HISTORY TRADITION

Lawrence Bamblett

[She] had photos of everybody, and them photos we’d just look at, she’d never leave you on your own to look at them, she’d be there watching making sure you didn’t take any. And she had photos of everybody, that’s how we knew who was who, you know right back to Grandfather Murray and Gran. Because I just used to ask, ‘[W]ho’s that?’, ‘[O]h that’s so and so, yes it’s your great-grandmother’. And I think that’s probably why I like to keep my photos to show the family, it goes from generations to generations, and they keep them, but I hope they keep my photos that I’ve got, I’ve got about two big port loads, you know to show the kids and that. And when I had the camera be everlasting taking photos, kids get their photos, school photos, I keep all that. But I tell you what some of them come along and grab them, take them and then you look for the photos, wonder where this one got to, where that one got to, and you’re searching for them and you find they’re missing. That’s why I think she used to make sure she was there when we were going through the photos. So like I say, it’s just like a book, you go through and show them and tell them, the kids and they’re good memories.

(Margaret Murray)1

FIGURE 1: Margaret (left) and June Murray (right) reading photographs to relatives at Erambie, 2011.

INTRODUCTION

There is a joyous scene of storytelling that is a constant and reassuring part of everyday life for Erambie Wiradjuri. The scene involves a group of senior Wiradjuri women and men sitting at a kitchen table, poring over and reading photographs. They often spend entire days sharing stories over cups of tea and informal meals. They find much enjoyment in group storytelling, and delight in back and forth banter and the reaffirming discovery of memories of the past. Interested young people are welcomed into the group to share the warmth and humour, and to observe and participate as the history of a whole community is told. Interest in community history and photographs grows out of these happy times in the company of gifted storytellers. Good memories are created as old memories are shared across generations. By returning to, and at times recreating storytelling, we are able to reflect on the ways that Erambie Wiradjuri have incorporated photographs into the oral history tradition of the community.2

The ancient Wiradjuri words for ‘teacher’ (muyulung) and ‘story’ (giilang) are no longer in everyday use at Erambie. However, these words falling into disuse does not mean that the role of teacher/storyteller does not persist in contemporary Wiradjuri life. Erambie people love nothing more than taking time to sit and yarn. A few years ago I was walking the streets at Erambie when I noticed that every home had a lounge suite or table and chairs in the front yard. In the evening people filled the chairs and lounges and it seemed like everyone in the community was having a yarn with someone. At my mother’s house a group of women were talking about their memories of childhood. An open tin of photographs sat in the middle of the table and the women looked through them as they spoke. June Murray (Figure 2) explains their use of photographs as something that was appropriated into what they were doing:

Photos fitted in there. We’ve done a lot of storytelling with our photos. If you can look at photos, that seems to bring back those memories. To me it brings my memories back more brighter in what happened. It does certainly prompt it…When you lose them, you lose a lot of your memories.

The use of photographs in storytelling among Erambie women has developed over time. Macdonald writes that Wiradjuri women have incorporated photographs into their storytelling for more than a century. She adds that Wiradjuri people altered their ideas and rituals about death and grief in order to include them.3 In the quote that opens this chapter, Margaret refers to photographs being used by ‘generations to generations’. She remembers seeing older people with photographs, but can only say earlier generations ‘must have’ used them in storytelling because she remembers being introduced to older people through photographs. June adds that ‘They all had their own photos, especially the real old ones and a lot of those we lost down the track.’ June recalls photographs being special to her parents because it was ‘their family they were collecting’ on their walls and in reused biscuit tins. Even though photograph collections started at the very least with her grandparents’ generation (born during the 1870s), June considers the use of photographs in storytelling to be something that was developed more by her generation.

Why do Margaret, June and their peers invest in photographs to the point that Margaret estimates that her ‘port loads’ of photographs number in the thousands? Perhaps because photographs did become more accessible — Margaret mentions the availability of Box Brownie cameras as one of the reasons collections grew. As collections became established, they started to be used to further individual, family and group interests. My observations and interviews confirm Macdonald’s assertion that snapshots became a source of capital in social relationships for Wiradjuri women. Among other uses, photographs help construct portraits of families, add truth to lineage and provide access to people who are no longer there.4 They also add to the identity of the collector by making connections to people and places. Margaret is respectfully referred to by her peers as a walking encyclopaedia due to her large collection of photographs and her knowledge of community history. My interest here is with the aspect of social relationships that deal with representations of identity — I am interested in the ways that photographs of people from Erambie are read and interpreted in the construction of Wiradjuri identities.

FIGURE 2: Margaret Murray incorporating photographs into her storytelling.

MEANING AND IDENTITY

There is an important photograph of Jane Murray that was probably taken during the 1920s, at the beginning of the ‘mission era’ at Erambie (Figure 3). It was taken in the yard of the doctor’s office where she worked. It is the best quality of the few remaining photos of the community matriarch. Erambie storytellers make use of this photograph — which they say is an excellent likeness of the dignified and much-loved leader — to tell stories about a lot of topics. Dozens of narratives are read from it, but they draw mainly upon her likeness whenever they engage with a wider discourse about race.

In 1999 I witnessed a discussion of this photograph that left me determined to prove that Jane Murray was Koori. A group of Erambie elders was seated around a table talking and shuffling through a photograph collection. The most senior woman in the group held up a copy of this photograph and said that ‘she was a wonderful woman’, and ‘she brought me into the world under a tree on the mission’. The next thing she said remains in my mind as clear today as when I heard it. She said, ‘You know, she was a “negress”’. Another woman asked, ‘What makes you say that?’ The reply was that it was the way she dressed, her tightlycurled hair and her singing voice that proved she was a ‘negro’. The discussion moved on when no genealogical evidence could be recalled to settle the matter. The idea that one of the women held up by many to be representative of a group of cherished Wiradjuri women was not in fact Koori did not sit right with me, and I have been searching this photograph, and others, attempting to read genetic features for the truth about Jane Murray’s lineage ever since.

Two primary readings of this Jane Murray photograph have emerged since that day. First, Murray’s granddaughters June and Margaret read the photograph in ways that reinforce their family’s special position of leadership within the Erambie Wiradjuri community. June says that the photograph accurately depicts the ‘dignified’ and ‘proud’ woman that she knew: ‘She used to tell me, “stand straight and hold your head in the air”. That woman has always been the same, head in the air, and that’s the sort of person she was.’ Using this photograph, June tells a story of a universally respected leader. Margaret reiterates June’s (and other community members’) assessment and adds that a doctor in Cowra held their grandmother in great esteem, and even boasted about her ability to treat ailments and birth children. The doctor, Margaret says, told people, ‘If Janey don’t know, then you come to me’.

The second common way I have seen this photograph read is in response to representations of Koori identity. The women who briefly debated Murray’s background in 1999 also mentioned a 1934 Cowra Free Press article that reported remarks made about Kooris by the white mission manager. The manager reportedly told the Cowra Teachers Association that ‘We people of today know little of the better class of black, and judge the race upon the class we do know.’ He went on to describe ‘Aborigines’ as a ‘child race’, which was rapidly heading towards extinction, before concluding that they should be treated as children. Some of the group recommended caution at labelling Jane Murray anything but Koori. They said that claiming that this capable senior woman was not Koori might be seen by some to support the ideas expressed by the manager.

No one still living can say for certain whether Jane Murray was Koori. That is not to say that there are not strong opinions either way. June says that her older cousins claimed her grandmother was a ‘negro’. However, when another relative made the same claim to one of her peers (and used this photograph as evidence), it was dismissed as ‘nonsense’. After reading a 1939 inspector’s report to the Aborigines Welfare Board that claimed strong ‘negro blood’ in the community, even outweighing the Koori blood in many cases, Margaret wondered whether the claim was an attempt to discredit and undermine the authority of the community leaders.

It is frustrating that I have not found a record of Murray speaking directly about her racial background. However, there are two newspaper articles that tell us how she was described (and she would have been aware of these descriptions) in the public discourse on race. During a 1920 appearance as a witness in a court case she was described as ‘an aboriginal’ while a young man from Erambie was described as a half caste.5 Cowra newspapers at the time reported the detail court officials went to in order to establish an Aborigine’s exact caste. In 1926 a magistrate is quoted in the Cowra Free Press defining the term ‘Aborigine’: ‘The word “Aborigine” under the Act means any full-blooded or half-caste aboriginal native of NSW.’6 This indicates that in 1926, at least, Jane Murray was legally considered to be Aboriginal (she would have to be at least a half-caste to be called Aboriginal in a courtroom). A second Cowra Free Press article in 1926 reported on a controversial move to expel the Murray family from Erambie.7 This second article offers further clues to Murray’s background. At a public meeting held to challenge the expulsions, an inspector from the Aborigines Welfare Board read out the mission manager’s duties. They included a clause to ‘discourage the presence of further half-castes on the mission’. The inspector also announced that Jane Murray did not accept rations even though she was entitled to receive them. Jane Murray is quoted as excitedly reacting to the threat to expel her family from Erambie by saying, ‘Why don’t you put off the half-castes and quarter-castes? We are the original owners.’ Murray appears to be saying that she is more Koori than a ‘half or lesser caste’ person. That her response about caste was not questioned during this heated confrontation by the government officials who recorded the ‘caste’ of a person as a matter of course, along with her eligibility to receive rations, suggests to me that she defined herself as Aboriginal.

Further evidence that Jane Murray identified as Aboriginal can be found in another newspaper report about her family. Her well-known boxing son Doolan was described in the Cowra Free Press as ‘a true son of Australia’.8 When Jane Murray passed away in 1937, the Lachlan Leader obituary classified her as ‘one of the oldest aboriginal residents of Erambie’.9 Also, her maiden name was Morey and her mother’s maiden name was Lane — there are Moreys and Lanes buried in the Koori cemetery at Brungle Aboriginal Station, where her family had lived. Historian Peter Read has published oral history testimonies from Erambie residents who knew Jane Murray, which give still further clues. Read found that Murray was one of a group of strict senior women who refused to speak Wiradjuri outside their own peer group. Her oldest son, Frank Broughton, is also quoted in Read: ‘My mother could speak it [Wiradjuri].’10

All of the above evidence does not dismiss June’s or Margaret’s long-held belief that their grandmother was a ‘negro’ who found a home within the Wiradjuri community.11 After discussing evidence to the contrary, June remained adamant in her belief: ‘I still think she was not an Aboriginal. That’s what I think. Her features, everything was different. You know by looking at her and the way she was dressed.’ Looking at the photograph, June compares Jane to her maternal grandmother:

She was quite different to Granny Dolly [who] to me was the full-blood Aboriginal woman. Granny Dolly looked more Aboriginal and tribal. Between the two grannies, one was different to the other in that way. And, one looked real Aboriginal and of course she spoke the language. I’ve never seen Granny Murray speak any [Wiradjuri] language. It was him [Harry Murray] and Granny Dolly.

After further reflection June illustrates the uncertainty associated with her grandmother’s background when she adds:

But I wonder you know, I’m still chasing to find out who she was. Whether her father was African or something. We’ve got her features, see it in Dad [Doolan Murray]. Some said she was and some said she wasn’t. So, it might have been just talk. But, we looked at the way she was. It’s still the big question. I’ve just got to know more about her.

Given the attention to detail about caste and race in government documents and even Cowra’s newspapers at that time, it is unlikely that Jane Murray would repeatedly be mistakenly described as Aboriginal. It makes sense, then, to say that Jane Murray was at least part Koori. However, the search raised an important question about why people are concerned with this woman’s racial background. British cultural theorist Stuart Hall describes why classification of this type is important to people:

Classification is a very generative thing…It is not just that you have blacks and whites, but of course one group of those people have a much more positive value than the other group…[anthropologist] Mary Douglas describes this in terms of what she calls ‘matter out of place’…You know exactly where you are, you know who are the inferiors and who the superiors are and how each has a rank.12

Some of the narratives of this photograph classify and re-classify Jane Murray’s identity in relation to ideas about race. These narratives undoubtedly responded to other representations. So, one reason June and Margaret talked about the way that their grandmother carried herself was to respond to a discourse of deficit where the racial identity of Kooris is assumed to be inferior. The readings of photographs came after decades of stories told to counter negative representations of Kooris.

BANKING IDENTITIES

Wiradjuri storytellers paint pictures of wonderful community crafted through impressive leadership. One example of this is a photograph Margaret owns of her parents inside their humpy in the Frog’s Hollow Wiradjuri community (Figure 4). It was taken in 1960 by a white newspaper photographer who Margaret says wanted to write a story about Koori people. She chose the photograph from the thousands in her collection to use as she told me a seemingly well-worn story (although it is the first time I have seen this photograph and heard of this particular event) about how her father represented the Wiradjuri community. The photograph, and the story Margaret tells about how it came to be, communicate a range of ideas about Aboriginal people.13 The reading of this photograph is an excellent example of a positive everyday story, told and retold within the Koori community and strategically shared with outsiders.

FIGURE 4: Herbert ‘Doolan’ and Ethel Murray with grandchildren at their Frog’s Hollow home.

Wiradjuri storytellers bank positive images of individual and group identities partly to balance the steady flow of negative representations. African-American teacher bell hooks defines ‘banking’ as a method of education where the students are ‘memorising information and regurgitating it’ as ‘knowledge that could be deposited, stored and used at a later date’.14 hooks sees little value in this method. In contrast, Wiradjuri storytellers place great value on banking knowledge as a culturally responsible way to teach. Again, this is probably in part a reaction to representations that assume Kooris have ‘lost their traditions and “failed” to become the citizens expected of them’.15

Both Margaret and June told a story about a community, and a leader, who understood that a photograph can produce an important representation. Participating in the making of this photograph indicated ‘a sophisticated awareness of white discourse’ within the community.16 Margaret reads the photograph in this way:

He said, ‘It’s for a good cause’, that’s when they were fighting for the Three Way [a yet-to-be-built Wiradjuri community in Griffith, New South Wales] homes. ‘They can come into my home,’ he said. ‘It’s clean, they can take photos and just show the white man how we’re living,’ but they were humpies, built out of tin, kerosene tins packed together.

This is Margaret’s photograph. She was present when it was taken. Therefore, it was her story to tell. June supports Margaret’s story and adds her own reflections:

You wouldn’t think they’re coming from a humpy. To me, when I look at that picture I feel saddened that my mother never had the privilege to live in a house. Dad said, ‘You can come and look in here if you’re doing something good for the community.’ Invited him [a local newspaper photographer] into the house and they were surprised to walk in to see how nice and clean the little humpy was. There were flowers and a tablecloth on the table. So they showed they were clean-living people, even though they lived in humpies.

Both ladies add further to their carefully crafted family portrait with personal observations of their father. Margaret (accurately, I am told) credits her father with social and material improvements at Frog’s Hollow: ‘This old man must have had a good education. He used to do all the writing [letters to government agencies] when people asked for help.’ To Margaret, her father represented a typical Murray man, because they were ‘always doing things to help their people’. June points to parts of the photograph as she adds:

Again he’s fighting for his people. They built the houses for them then. Looks as though he was starting to age there. But he was still helping his people. They leaned on him. He looked proud to me. That’s how I remembered him there.

My reading of the photograph, and its accompanying narratives, was primarily concerned with finding a truth of lineage. I had optimistically hoped that a close reading of this photograph of Doolan would prove the Koori identity of his mother. For me, the image of one of my heroes as an older man was confronting, as well as comforting.17 As a young athlete Doolan looked like the other Wiradjuri men from Erambie. Here, he did not look as Koori as he had then. Seeing him as an older man, living away from Erambie, was also an unwelcome reminder of what our community lost due to his absence. On the other hand, it was comforting to see the humble family man from the stories I had memorised. This photograph was made to tell something about Wiradjuri people. It neither proves nor disproves racial identities. It does, however, make finding proof that the Murray family exemplify Wiradjuri excellence even more important, because it shows that our elders recognised the importance of representations of race.

While I found some comfort in the ideas revealed about Kooris in the image of Doolan Murray in his humpy, the ‘mythical sense of knowing’ the man in the photograph was equally important.18 The next photograph Margaret shared with me (Figure 5) caused some anxiety because it challenged a basic assumption — something I thought I knew about him. Margaret tells me that this man was her father, and I see an elderly man who I do not recognise. Doolan had left Erambie when my mother was a young girl, and he passed away when I was a baby. I knew him through storytelling — a few photographs of him as a young athlete, and my own newspaper and document-based research. The image of a man whose sporting prowess, leadership abilities and collectivist view of life (which he focused on community building) represented a prominent and powerful image of what it means to be a good Wiradjuri does not match the man in this photograph. This man looked like an African-American sharecropper from an Ernest Gaines novel. June sometimes jokingly likens her younger brother (Doolan’s son) to the ‘Chicken George’ character from the television series based on Alex Haley’s novel Roots. The man in this photograph would not look out of place sitting proudly and defiantly on the porch of a plantation shack in Gaines’ A gathering of old men. Looking at this man, I wondered what my relationship with him would be if he did not physically represent a Wiradjuri hero. The value of this photograph, as Macdonald suggests below, is uncertain because it can be read as not clearly connecting a community hero to a Wiradjuri identity.

Through the photos, one gains access to the person who is no longer here. Photos have taken on the role of linking the living and the dead in ways that were once mediated through myth…Photos are the material evidence of connectedness to what is now ‘past’. The more photos connect, the more they are valued.19

Other Kooris say Doolan looks Aboriginal. Immediately this photograph becomes more valued. Is it the emotion added through narrative that changes what I see? The answer seems to be that it does. It is certain that the narrative of Jane Murray’s image affects the ways this photograph of her son Doolan is read. Equally important to the way emotion affects a reading is the fact that we at Erambie are brought up to believe Doolan Murray was one exceptional example of the value of Wiradjuri traditions and values. His image may be our most important representation because he was Cowra’s first sporting idol. Other men from Erambie are remembered as examples of what is good about the community, but none has the broader local profile of the feted boxer. We are connected to him, and he to our Wiradjuri forebears, through the continuity of the traditions and values we are told he represents. This is consistent with Lear’s assessment of Crow child-rearing practices:

Children were brought up in ways meant to instill the excellences of character as understood by the Crow. These traditions may have differed on particular virtues — or excellences — but they agreed that the virtuous person is one who has the capacity of character and body that enable him or her to lead an excellent and happy life.20

Our community is connected to the past through images and representations of men like Doolan Murray. Therefore, any questioning of Doolan’s Wiradjuri identity may weaken the community’s connectedness to past Wiradjuri identities.

The clothing that Doolan Murray wears in this picture contributes to how I see him. He looks African-American to me partly because of the way he is dressed. Another photograph of his younger brother seated beneath a gum-leaf shelter, his body painted as a tribal man and a boomerang in hand for a 1950 parade float, can be used to demonstrate this point. Doolan’s younger brother does not look remotely African in appearance. Countless times storytellers have produced photographs of Erambie men dressed smartly as evidence of their character. They use these photographs, and the dress sense of the men, as an example of Wiradjuri excellence. Here, the same focus on clothing raises questions about Doolan’s identity. I know him totally based on what I am told.

Photographs draw us into relationships with the Erambie elders who we idolise.21 They draw me into a relationship with the subject and the narrator.22 Photographs link generations, as Margaret has noted, and they are used to teach values. Storytellers teach about values using biography. Values are taught to younger people by telling stories about how cherished elders responded to events and issues. For example, when Margaret explains why she was ‘very proud’ to nominate this photograph of her father to be enlarged and displayed in his honour at a new Griffith Koori medical centre building, she adds a reading of the image:

FIGURE 5: Herbert ‘Doolan’ Murray.

[T]he kind of man he was, his handshake was his word. He always had a suit on, hat on, he’d tip his hat to the ladies, talk to the babies. Down in Griffith, they all used to know him. Mister Murray, there he goes. That’s from this old feller [pointing to her father’s picture].

June uses the photograph to explain why her father was being recognised close to four decades after his death:

They should recognise him. He did a lot for the people down there. Even in his old age he was still helping them out. He deserves to have something there…When he died there was no money for his funeral, to bury him. When he [Doolan] paid for his own funeral, it was by the shake of a hand you know, they trusted one another. Him and the undertaker, no receipts or anything were given out and when he [the undertaker] died they couldn’t find receipts. They said Doolan had come down all the time and anyone passed away in the Three Ways or anyone [Kooris] down here, he’d come and help them and made arrangements to get them buried. The money went. So, that’s how good he was and he never had nothing to bury himself in the finish.

This family snapshot of Doolan will be used to make a public representation of the achievements and character of a Wiradjuri leader. It will add the context of time and history to contemporary advancements by recognising the efforts of past leaders. Could another way of reading this photograph involve the attribution of ‘negro’ blood, which would for some people amount to evidence denying the existence of such excellence within the Koori community? Historically, advancements and positive achievements within the Erambie community were often explained by some as the result of efforts by white authorities. Later, the alleged presence of ‘negro’ blood was also used for this same purpose. Advancements and achievements at Erambie were not viewed by authorities as evidence of Wiradjuri excellence.

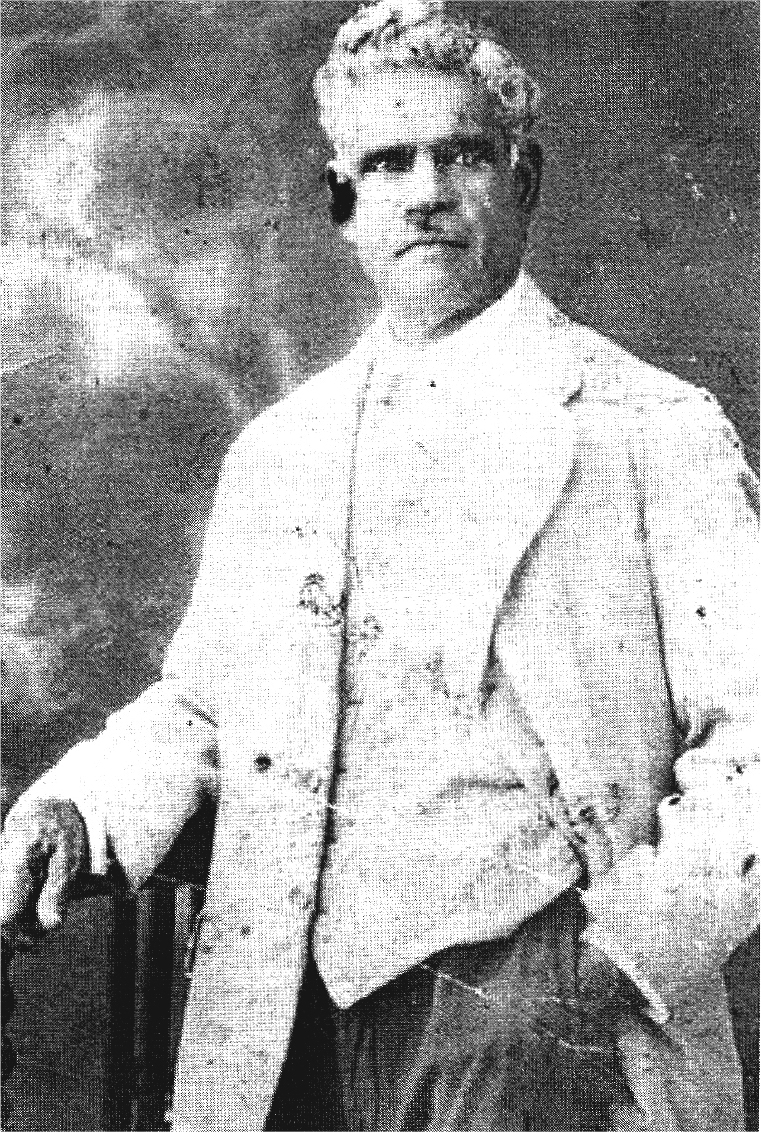

A BIDJA

In contrast, there is another oral history told where Wiradjuri elders developed a strong community in spite of outsiders. This 1920s photograph of Erambie patriarch Harry Murray (Figure 6) is as important to the community as the one taken of his wife, Jane, around the same time.23 It is distributed among community members as a treasured reminder of Murray’s achievements on behalf of Wiradjuri people. By reflecting on the ways that this photograph has been used by Murray, and drawing upon analysis of parallel stories of cultural transition, we can gain a greater understanding of what he was hoping to achieve by sitting for this portrait. This admittedly speculative analysis, focused as it is on narration of the image, considers what the portrait of a Wiradjuri bidja (leader) means to the Erambie community close to a century after it was taken.

At the time this photograph was taken, the fifty-year-old Harry Murray had been an unchallenged leader at Erambie for more than twenty years. Read quoted Erambie residents’ summaries of Harry Murray’s position as leader. One resident told Read, ‘Everyone seemed to look to the Murrays…they were the first people to go to.’24 Another resident said, ‘The people would go and tell Mr Murray, and he’d tell Mr Constable [the first manager of Erambie Station]. He’d tell him, he wouldn’t hesitate. He never swore, you know. He said, “You can’t stand over my people”.’ Murray’s leadership was seriously challenged in 1924 when a government manager was appointed and the reserve became a station. Life on a managed station threw up challenges for the leader of the relatively free community. Erambie had been an unmanaged reserve gazetted in 1890 until a government ultimatum to either accept the appointment of a manager or have the reserve relocated further away from the town. Melissa Lucashenko asks her readers to imagine life with the kind of restrictions and intrusions on life that people faced on the managed stations:

FIGURE 6: Harry Murray Senior.

To gain some very slight understanding of mission life, think about your present boss. Now let’s say that this person will be boss, not just of your working hours, but of your entire life, for an indefinite period. It could be one year; it could be the next 20, until he or she is replaced, through a distant government decision, by another manager from an alien culture. Imagine that you need this person’s permission to leave your suburb, to visit another town, to be out after dark, to operate an electrical device, to chop down or plant a tree in your garden, to change jobs, to marry, to move house. Imagine that this person can fire you or provide you with a cushy job, remove your kids if he or she wishes, banish you from your home, cut your hair, order you flogged, fine you or imprison you without trial if you try to abscond. This person also controls your bankbook, which you probably have never seen. An important underlying assumption is that this person automatically considers you his or her physical, intellectual and social inferior. There is no system of appeal should you disagree with his or her decisions; there is no requirement on him or her to do anything other than keep you alive. Such was mission life for Aborigines throughout most of the 20th century.25

On top of the type of intrusions Lucashenko describes, Murray faced the additional challenge of a government attempt to usurp his leadership. Imagine being a fifty-year-old grandfather, a respected and accomplished leader within a community, and having this type of control forced upon you.

Comparing the ways that other leaders dealt with the new way of life on managed reserves offers a way to understand how Murray responded to change. Within a few decades of each other, Comanche Chief Quanah Parker and Wiradjuri bidja Harry Murray posed for strikingly similar photographs. Both images are typical of portraits of prominent citizens made at that time. They pose against sparse backdrops in suits and hats (Murray’s suit jacket and hat are white, his trousers dark; Parker’s entire outfit is dark in colour). Murray and Parker wear the formal dress of white people in these photographs. However, Parker made a public commitment to ‘taking the white man’s road’.26 Murray did not make this statement verbally. However, he and Parker both made visual statements towards a commitment to the white man’s road by dressing in a way that the white man might understand as gentlemanly. This suggests that Murray understood the need to adjust the way he led. Moreover, the photographs suggest that both Murray and Parker constructed an image of their leadership using the new language of the photograph as a way of communicating and reinforcing their place to people outside the community. The two established leaders needed to show another group of people, using those people’s language, that they were leaders.

Murray and Parker’s paths to the white man’s road were similar. Respective governments wanted to deny their core identities as warriors.27 Both moved their people into government-controlled reserves in attempts to ensure survival. Harry Murray played a key role in having a school built at Erambie. He oversaw the running of the school, including making recommendations about the teachers who were employed at the school. He requested a Koori teacher and an evangelist from Cummeragunga be appointed at the Erambie school. He was buried in the Catholic cemetery at Cowra. Murray was also ‘keen to effect’ changes discussed with Cowra Council staff.28

Both men tried to manage how their identities were represented. Gwynne has described how Parker refused to recount his deeds as a warrior, who killed many, in an attempt to control how white people viewed him.29 Murray once threatened to sue a mission manager for a libellous attack on his identity as a friendly, respectable and upstanding member of the community. Parker entered into the cattle industry, while Murray operated a sheep-droving business. Both saw their people line up to receive meagre rations as a replacement for discontinued ways of living. Parker joined the ration line, while Murray refused. Both leaders were confronted by white men who were greatly respected by their government employers and tasked to subdue them. On the reserves, both men were living in close proximity to other leaders. Whereas Parker was condemned as a sell out by his own people (rival leaders mainly, who were unable to match Parker’s political skill, having positioned himself as a leader above others), Murray managed to retain support among Wiradjuri people living at Erambie.30

For all his commitment to engaging with European ways and accessing their services, Murray continued to speak the Wiradjuri language, despite it being banned on the station. He worked to build Erambie as a separate community, which accessed the mainstream on its own terms. As Margaret and June have noted, he stressed that Wiradjuri people and culture were equal to what the white man had to offer. June recalled that racial pride was a key lesson he passed on. Both leaders were at times enthusiastically cooperative or fiercely oppositional to change. This put them both at odds with government intentions to assimilate their people into white society.

Government imposition of station/reservation regimes on Wiradjuri and Comanche people was prefaced by a discourse of inferiority. Gwynne’s account of how the United States government moved to end Comanche ways of living and confine them to a reservation demonstrates how government responded to representations of Comanche as savage and uncivilised.31 Cowra newspapers had long represented Kooris as inferior to white people. The Cowra Free Press described a ‘dying’ and ‘childlike race’, and regularly headlined articles about ‘coons’, ‘nigger trouble’, ‘darktown’, ‘abos and liquor’ and a ‘beastly Queenslander’. On 12 February 1924, the Cowra Free Press published a joke about the Koori caricature ‘Jacky’.32 The joke said that Jacky had been denied work by a white boss because there was not enough work for the white men already employed. The punch line was, ‘Jacky said, “The little bit I’ll do will not make a difference”.’ Just months prior to the ‘Jacky’ joke, the 10 July 1923 Cowra Free Press reported that Harry Murray had ‘expressed great indignation that [a Koori man labelled by the newspaper as a ‘filthy nigger’] had been described as a resident of Erambie Mission! He was a “stranger to all residents there” and had been “recently warned off the Goollagong camp”.’33 Harry Murray challenged the idea that Aboriginal people were inferior when he confronted newspaper representations that painted Kooris in a bad light.

Black feminist writer Audre Lorde writes that for people located ‘outside the structures’, the ‘master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’; Lorde concedes that, while engaging with the master’s tools will not bring about ‘genuine change’, it can ‘allow us to temporarily beat him at his own game’.34 I am suggesting here that Harry Murray posed for his portrait as part of a broad understanding of the importance of representation of his identity as a leader. He understood that Wiradjuri excellence paralleled what was considered excellence on the white man’s road. The man that excelled among his own people also excelled, and was seen to excel, in white man’s terms. He presented an individual image of himself as a man worthy of respect in ways that white people understood. This may have been at odds with Wiradjuri ways, where leadership was demonstrated according to collectivist values rather than individual promotion.

When the inevitable conflict occurred between Murray and the government manager, Murray used the individual image of a leader he had created to counter a generalised image of the uncivilised black man. He then appealed to the people of Cowra to support him as a man who deserved to be treated fairly. When the government officials and the mission manager tried to discredit Murray with accusations of bad character, they did not fit with the image people had of him, and were therefore not accepted.

The Cowra Free Press published three articles about the attempt by the manager to expel Harry Murray from Erambie. A Friday 28 May 1926 account of ‘The Murray case’ outlines how local white people supported Murray against the manager and the Board. The article, much of it a transcript of the public inquiry, suggests that Murray drew on his reputation within the wider Cowra community to out-manoeuver the manager and the Board by pitting his representation of his own identity against theirs. Murray, and his family, had been the subject of many complimentary stories in the Cowra Free Press over many years. This, coupled with business and personal relationships he had developed, meant the Board and the manager (who had lived in the town for only a couple of years) would be pitted against the prominent local citizen depicted in this photograph.

The article begins by restating that Murray had ‘for many years enjoyed the reputation of being the “uncrowned king” of the local Aborigines’. An incident between Murray and the manager is then described, where Murray ‘took strong exception’ to the manager’s treatment of two Koori men at Erambie. An argument followed. At this point, the article reports that a local health inspector, two local merchants and two business associates of Murray provided glowing accounts of him as ‘honest’, ‘straightforward’, ‘trustworthy in every way’ and ‘clean living’, a man of ‘good character’. The Board representative countered that the manager was worthy of praise and that Erambie was the ‘worst’ reserve in New South Wales until he took control. Any positives that could be attributed to Erambie were ‘as a result of the efforts of the Aborigines Protection Board officer’. He added that the Board was not seeking to have Murray ‘humble his manhood in any way’ but merely to ‘behave’ and ‘conform to the rules’. At this point, it is reported that Murray’s white supporters challenged the attack on Murray’s character and the Board’s decision to expel him. This drew accusations from the inspector that people would be surprised at ‘what sort of man Hy. Murray is’, and that the ‘Murray you see in town, with his glib tongue, is vastly different to the Hy. Murray that comes back to the camp’.

Other insulting accusations were made against Murray. However, they were disregarded, as people trusted the Murray they saw in town — some had stated that they had known him for more than thirty years — and accused the manager of threatening to shoot Murray. Neither the Board representative nor the manager denied the threat had been made but suggested Murray had been ‘treated leniently’. Murray won a compromise and the expulsion was not enforced. Ultimately, however, Murray’s victory proved to be as temporary as Lorde suggests.35 Even though he saw off a number of managers, the constant intrusions led Murray’s sons to leave the mission. Margaret describes how her father finally left the managed station after his father’s death to live on unmanaged reserves in Victoria and southern New South Wales.

Well the manager, I remember, [we] was over working on the cherries, Dad had us over there, we were only kids. Old Fuller, he was the manager here then. We came home in the middle of the night and Dad went over to tell him we were home the next morning. Fuller said that Dad should have come over last night and reported. In the middle of the night! He was putting us kids down and making a fire. Well that was it. Dad said ‘No. I’m leaving’. Just packed up and left.

This photograph of Harry Murray represents him accurately as a leader and prominent citizen of Cowra. I have suggested here that Murray used a portrait of himself to challenge representations of his Koori identity as inferior or ‘childlike’ and in need of control by government authorities. In addition, he used the photograph to continue individual, family and group narratives about his place within the Erambie community, as well as more generally in the wider community.

Margaret and June use this photograph of their grandfather to continue building their family portrait (Figure 7). Margaret suggests that the manager and the Board wanted her grandfather expelled because of the respect people had for him as a leader. She says that the photograph is a good representation of the type of man he was:

He was always like that, he was always dressed. He was never a shabby old man. Dad was the same, he was always dressed, hat on, tip it to the ladies. He was one of the real old gentlemen because all his photos are the same. I’ve never seen him untidy or anything.

FIGURE 7: June Murray reading a photograph of her grandfather, Harry Murray, at Erambie, 2011.

Margaret reads this photograph as further proof of her family’s place within the Erambie community:

Grandfather was the boss of the mission, he never swore. I think he was very well respected because even the police would go straight into other houses. But him, No! That’s the kind of man he was, they had respect for him. Today, everyone is at a distance. Everyone started moving away. You know, kids growing up somewhere else. But the mission there, like I said, very close.

June also built on her family portrait when she delivered the following welcome to country at a Friday 8 July 2011 National Aboriginal and Islander Day Observance Committee (NAIDOC) event:

It is customary to acknowledge traditional custodians at an event like this one. My family, the Murrays, have always been connected to this country. We are the recognised custodians. Today, I would like to acknowledge all of our Wiradjuri ancestors with special mention of the contribution of my grandparents Harry and Jane Murray, who built the community we today call Erambie. They managed our people’s transition into a modern world with pride and dignity. They represented all that is good about being

FIGURE 8: June Murray reading a 1937 Erambie community portrait, 2011.

Wiradjuri people. They passed down Wiradjuri values and connection to this place through generations. They were open and welcoming leaders who demanded respect for tradition and place. In the spirit of my grandparents, I want to welcome you today to Wiradjuri country. We acknowledge today the contribution and values of our people of the past as we look toward the future.

Later that same day, June tells me that her grandfather showed strength and courage to lead the community through great changes:

Tribal part, they were coming away from the tribal, so his father [Samuel Murray] must have been a great man too…Well he stopped them [the police] taking Mum back to the station she was working at. He told them when they came there to take her, she went there [to Harry Murray’s house at Erambie] for shelter, and they wouldn’t dare enter his house, so she stayed there.

June and Margaret have lived away from Erambie for decades. They left the mission with their father, Doolan, when they were still children. Still, Erambie remains home to them — they visit often — and they are considered community elders and storytellers. A measure of the respect still held for them and their family within the Erambie community is that June was invited to perform a welcome to country without drawing criticism from within the community. Anyone familiar with the internal politics of a Koori community will understand the significance of no one challenging June’s right to deliver a welcome to country. This is in part due to the family portrait constructed through storytelling using photographs. As they both often say, photographs are proof not only of their connection to Erambie, but also of the special place their grandparents hold as leaders and representatives of Wiradjuri people.

CONCLUSION

What do photographs mean to Wiradjuri people today? Wiradjuri culture was not ended by colonisation. Of course, drastic changes occurred to everyday life and ways of living. But change does not equal ending. In some instances new technologies and ways of doing things were compatible with existing practices, and so were incorporated into a dynamic and continuing culture. Photographs are valued based on how well they link people to places and the past. The real value of photographs is that they connect people in the present. They tell us something about Wiradjuri people, even those that are not in the frame. Wiradjuri storytellers have appropriated photographs into what they do because they fit in to the joyful scene of people sharing stories. Relationships are built across generations and over piles of worn photographs. The storytelling scene acted out at the kitchen table covered in photographs repeats and continues the meaning and process of an ancient Wiradjuri oral history tradition. Within this tradition the uses of photographs are many and varied. This reflects the oral history tradition they have been incorporated into. Photographs trigger a number of narratives about representations of identity and place. These narratives are further complicated as they occur within a wider discourse about race. If the use of photographs by Wiradjuri storytellers can be summarised, it would be that they matter because representations matter. They fit in.

NOTES

1. Interview with Margaret Murray at Erambie, Friday 8 July 2011. There has been some very minor tidying up done to interview transcripts (quotes) to assist with clarity. Care has been taken not to alter meaning and both ladies interviewed have read and approved all changes that were made.

2. Two knowledgeable and gifted storytelling sisters, June and Margaret Murray, graciously agreed to share their photographs and participate in interviews. Together we chose four ‘mission era’ photographs of prominent Wiradjuri elders from one family (the Murrays) and they read them to me and reflected on their value to the community. It is normal and proper for me to refer to Margaret and June as aunties because they are my mother’s first cousins. However, it seemed to get in the way of the story to add ‘Aunt’ to each of the many references I make to them, so I decided to refer to them by their Christian names throughout the text.

3. G Macdonald, ‘Photos in Wiradjuri biscuit tins: negotiating relatedness and validating colonial histories’, Oceania, 73(4):225–42, 2003.

4. R Barthes (trans. by R Howard), Camera lucida: reflections on photography, Vintage Books, London, 1981.

5. ‘Alleged stealing in company: youth charged’, Cowra Free Press, 19 May 1920.

6. ‘Aboriginal couple on holidays’, Cowra Free Press, 21 May 1926.

7. ‘The Murray case’, Cowra Free Press, 28 May 1926.

8. ‘From the Cootamundra Liberal’, Cowra Free Press, 10 August 1921.

9. ‘Obituary: Mrs Harry Murray’, Lachlan Leader, 23 August 1937.

10. P Read, Down there with me on the Cowra mission: an oral history of Erambie Aboriginal Reserve, New South Wales, Pergamon Press, Sydney, 1984, p. 13.

11. P Rimas-Kabaila & Ed Radclyffe, Survival legacies: stories from Aboriginal settlements of southeastern Australia, Canprint, Canberra, 2011. Jane Murray’s marriage certificate lists her birthplace as Cootamundra, New South Wales (within Wiradjuri country).

12. S Hall, Race, the floating signifier, Media Education Foundation, Northampton, 1997, p. 3.

13. J Lydon, Eye contact: photographing Indigenous Australians, Duke University Press, Durham, 2005.

14. b hooks, Teaching to transgress: education as the practice of freedom, Routledge, London, 1994, p. 5.

15. Macdonald, above n 3, p. 239.

16. Lydon, above n 13, p. 23.

17. Doolan Murray’s sports career was a topic in my honours and doctoral theses. I have idolised him and other elders from Erambie since childhood. See L Bamblett, Our stories are our survival, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2013.

18. D Porat, The boy: a Holocaust story, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 2010, p. 218.

19. Macdonald, above n 3, p. 236.

20. J Lear, Radical hope: ethics in the face of cultural devastation, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 2008, p. 63.

21. ‘Elder’ is used at Erambie as a term to define leadership and age. It is also used to describe people who have passed away.

22. Macdonald, above n 3.

23. The photograph of Harry Murray is undated, so the 1920s date I have used is based on estimating Murray’s age by his appearance at the time it was taken. He looks as if he is in his fifties in the photograph, which would date the picture in the 1920s. This would date the photographs of Jane and Harry Murray I use in this chapter at the start of the ‘mission era’ at Cowra. Erambie regressed from a reserve to a government-run station in 1924. Margaret and June agreed with my estimates.

24. Read, above n 10, p. 14.

25. M Lucashenko, ‘Who let the dogs out?’, Griffith Review, 8(winter):133–46, 2005.

26. SC Gwynne, Empire of the summer moon, Scribner, New York, 2011, p. 285.

27. ibid., p. 259.

28. ‘The Murray case’, Cowra Free Press, 28 May 1926.

29. Gwynne, above n 26.

30. ibid.

31. ibid.

32. ‘Jacky to boss’, Cowra Free Press, 12 February 1924.

33. ‘A serious offence’, Cowra Free Press, 10 July 1923.

34. A Lorde, Sister outsider: essays and speeches by Audre Lorde, Crossing Press, Berkeley, CA, 2007, p. 112.

35. ibid.