Chapter 7

PHOTOGRAPHING SOUTH AUSTRALIAN INDIGENOUS PEOPLE: ‘FAR MORE GENTLEMANLY THAN MANY’

Jane Lydon and Sari Braithwaite

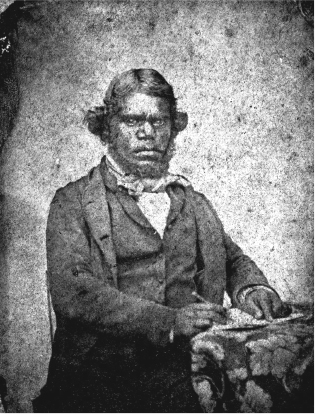

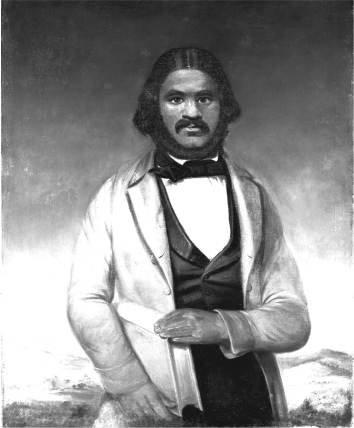

Tenberry (c. 1798–1855) was a senior Ngaiwong man from the Murray River who lived through his people’s first violent encounters with white settlers during the 1830s. In 1841 he was appointed native constable at Moorundie, the first European settlement on the Murray, after explorer and colonial administrator Edward John Eyre (1815–1901) became its Resident Magistrate and Protector of Aborigines. With Tenberry’s help, Eyre was successful in preventing further clashes between the local Indigenous people and overlanders travelling through the region. Settlers recognised Tenberry’s key role as a cultural mediator, and in February 1846 one newspaper account noted that:

Tenberry has always been on the most friendly terms with Europeans, and it is to his influence and co-operation that they, in a large measure, owe the peaceful occupation of the Murray River, and the happy establishment of amicable relations with the once hostile, and much-dreaded tribes of the Murray, Rufus, and Darling Rivers.1

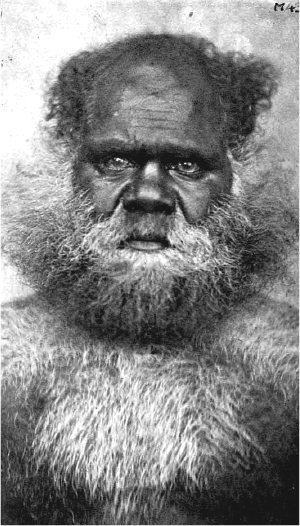

Tenberry’s remarkable early portrait survives in England, collected by a missionary who saw him as ‘King’ Tenberry, a ‘noble savage’ and guardian of tradition who was doomed to disappear (Figure 1).2 Although contemporaries may have seen Tenberry as a relic of the past, his photographic portrait brings him to life again, remaining a powerful testament to his strength and experience. The camera focuses squarely and intensely on Tenberry’s face, and especially his eyes, rendering his troubled expression with remarkable clarity. He is shown not as a ‘type’ but as an important individual in his own right, expressing his respected status within cross-cultural colonial society. His descendants value this portrait today as a record of a famous ancestor and his extraordinary life.

FIGURE 1: Tenbury (aet c. 60) Chief of the MURRAY BEND tribes. 1847. S. AUSTRALIA. Albumen print. Courtesy of the Pitt Rivers Museum, PRM1998.249.33.1. Moral/cultural permission Cynthia Hutchison and the Ngaut Ngaut Mannum Aboriginal Community Association.

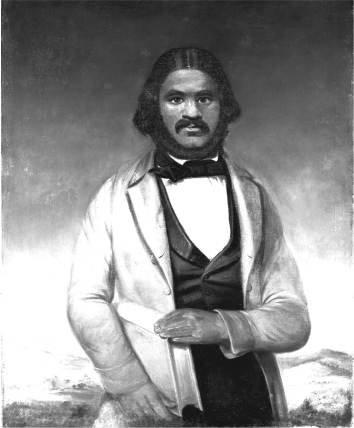

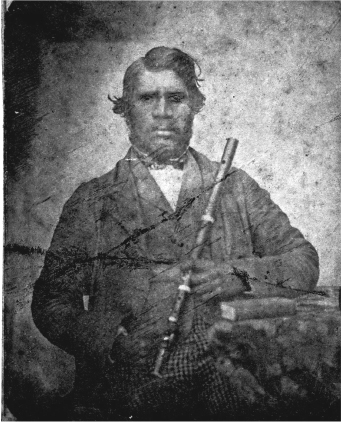

FIGURE 2: Jacky — now known as Master Mortlock. Ambrotype, c. 1855. Ayers House Collection, Adelaide, catalogue 4a, accession 0787.

Tenberry had seen profound changes to his world. The colony of South Australia was established in 1836, after the British Parliament passed the South Australia Act 1834, and rapid settlement soon saw the decimation of the Kaurna, upon whose traditional country the town of Adelaide was established. South Australia was the only Australian state to be settled entirely by free settlers under Edward Gibbon Wakefield’s scheme of small to medium agricultural landholdings. Although the Letters of Patent attached to the Act acknowledged Aboriginal ownership and guaranteed land rights for the Indigenous inhabitants, these provisions were generally ignored by the Colonisation Commissioners in London and white settlers, who followed the usual pattern of relations with the Indigenous inhabitants ranging from violence to accommodation.3 These complex relations were mapped through photography.4

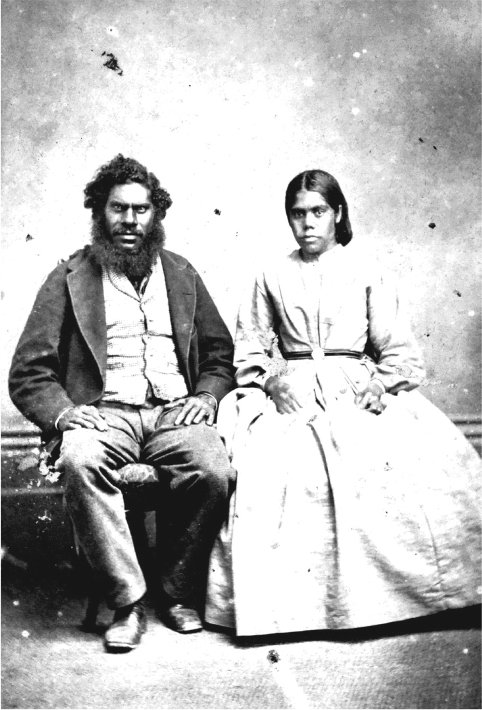

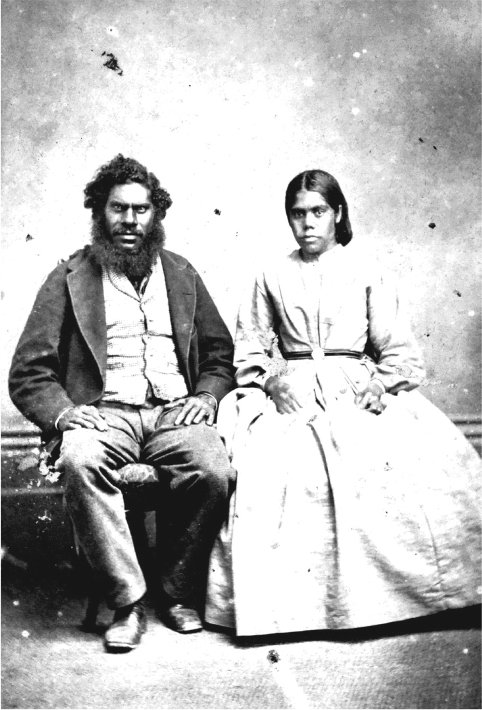

JACKEY AND JEMIMA GUNLARNMAN

Other early photographs reveal stories of adaptation, such as the portraits, made around 1860, of Tatiara couple Jackey Gunlarnman and his wife Jemima. They were servants of prominent pastoralist William Ranson Mortlock (1821–1884), and in a well-known portrait of Jemima, wife of Jacky and William Tennant Mortlock, Jemima holds the Mortlocks’ toddler son on her lap. Evocatively, the young William has wriggled during the long exposure required by the daguerreotype process and is a little blurred, but Jemima’s somewhat stern expression is clear and well defined.5 Jemima is neatly dressed and has her hair in long ringlets. Jackey’s ambrotype portrait (Figure 2) shows him dressed neatly in waistcoat, cravat and suit, seated before an elaborate painted backdrop representing a picturesque landscape that has been hand-coloured in green. Jackey is dignified and serious.6

These exceptional portraits testify to the couple’s unusual position in the new colony’s frontier society. Mortlock had settled in South Australia in 1844 and purchased the Yalluna run, twenty-five miles north of Port Lincoln, on the Eyre Peninsula, traditional country of the Pangkala and Nauo along the coast, and the Kokatha in the interior. Mortlock had supposedly ‘rescued’ Jackey from the Tatiara district in 1845, and persuaded him to work on Yalluna. Nine years later, Jackey and Jemima lived in a house that ‘contained three rooms, and was worth 5s to 8s per week as rent. He had lived there since last March twelvemonth. He could read a little and write after a fashion’, and was ‘said to possess a very fair degree of general intelligence’.7 The story was told that:

On one occasion, when Bishop Short was visiting the station, the prelate asked Jacky why he did not take a wife, and the native expressed his objection to marrying a woman belonging to another tribe. Next time that the Bishop journeyed to Eyre Peninsula he took with him a lubra whom he had secured in the Tatiara district, and introduced her to Jacky, who soon afterwards married her. The couple led a very happy and useful life on Yalluna.8

The harmonious picture this conjures up is undermined by other evidence for bitter conflict. The history of contact in the Port Lincoln district throughout the 1840s and 1850s was particularly violent and bloody, perhaps because of an earlier phase of contact with white whalers and sealers along the coast who had abducted Indigenous women. In 1859 one such incident involving Mortlock and his brother-in-law Andrew Tennant was reported in unusual detail, revealing the often fraught and brutal relations between settlers and the Indigenous people: the Government Resident at Port Lincoln described how a man named Colotoney had died of injuries allegedly inflicted by Tennant. Colotoney claimed that Tennant had ‘beaten him with waddies, had tied him up and whipped him with a stock whip and had kicked him — that blood ran down his legs — that he was beaten for allowing his sheep to mix with others’.9 Several statements by Indigenous residents of nearby Poonindie Mission and those living in camps around it endorsed Colotoney’s account. Yet the inquest was derailed by Mortlock, who initially tried to halt the inquiry on the grounds that ‘it might probably seriously affect the character of Mr Andrew Tennant, a young man just entering the world’; then he endeavoured to show that it was a frivolous proceeding by remarking that ‘everybody knew that it was general practice in the bush to thrash the natives when they deserved it, it being the only way of managing them’.10

Tennant was reported to have tortured and assaulted several other local Aboriginal men in various horrible ways.11 Colotoney had fled to Poonindie as a refuge, and the missionary Octavius Hammond clearly viewed Tennant’s behaviour as criminal, although his attitude contrasted strongly with those of Mortlock and his circle. Such evidence indicates that the Ayers House portraits were not an expression of Indigenous people as equals; rather, they emerge from a strictly hierarchical worldview in which Jackey and Jemima were valued in the subordinate role of servants.

‘THE NUCLEUS OF THE NATIVE CHURCH’: POONINDIE MISSION

By contrast, the remarkable series of portraits commissioned by Anglican clergymen at Poonindie Mission during the 1850s and 1860s express a conception of the essential unity of humankind and the equal capacity of their subjects in a distinctively inclusive vision of Indigenous people.12 These daguerreotypes and ambrotypes, held in British and Australian archives, were rediscovered during 2012 and mark a radical departure from contemporary — and later — photographs of Indigenous Australian people. They point to a rare visual theme that flourished in South Australia during these years under the impetus of Anglican Church leaders commemorating the achievements of Christianised Aboriginal farmers.

In 1848 the new Anglican Bishop of Adelaide, Augustus Short (1802–1883), arrived in the colony with his Archdeacon Matthew Hale (1811–1895). With Protector Moorhouse’s support, Short and Hale proposed the establishment of Poonindie, a ‘training institution’ on the southern Eyre Peninsula, where children and young adults could be further educated and Christianised, away from the ‘corrupting’ influence of their parents.13 By early 1853 the clergymen were delighted with their small flock, and Short later described how:

After hearing them, and asking them questions, I agreed with the Archdeacon that there was good ground for admitting them by baptism into the ark of Christ’s Church, believing them to be subjects of God’s grace and favour. We held regular evening service at sundown; and after the second lesson, I baptized Thomas Nytchie, James Narrung, Samuel Conwillan, Joseph Mudlong, David Tobbonko, John Wangaru, Daniel Toodko, Matthew Kewrie, Timothy Tartan, Isaac Pitpowie, and Martha Tanda, wife of Conwillan.14

Short’s and Hale’s vision was distinctive in defining the Aboriginal subjects as gentlemen, the ‘nucleus of a native church’. Short’s ideas about ‘civilising’ Indigenous people were shaped by his own upper-class worldview — including his experience of public school, the belief in personal demeanour as a sign of status, and the importance of cricket. Crucially, missionaries argued for the transformative potential of Indigenous people — often against those who argued for their essential difference on racial grounds. In the intensely politicised context of mid-century Victorian science, great weight was given to debates about human history and difference. In attempting to counter ideas of the essential difference of Indigenous Australians, visible evidence for achievements at Poonindie took on particular significance. Immediately after the group baptism, Short wrote of the young men:

I was agreeably surprised to see them nicely dressed in the usual clothing worn by settlers; cheque shirts, light summer coats, plaid trowsers, with shoes and felt hats—articles mostly purchased with their own earnings. They were better dressed than the labouring class in general at home… Not far off was a small native camp, and the contrast between these two groups would have convinced any candid observer of the truth for which the Archdeacon has always steadily contended, viz. that the Aborigines are not only entitled to our Christian regard, but are capable, under God’s blessing, of being brought out of darkness into light, and from the power of Satan unto God.15

In this way, Short conflated the appearance of the people of Poonindie, measured by their clothing and personal grooming, with their spiritual transformation. Portraits of the residents of Poonindie assumed value as missionary propaganda, incorporated into longer textual narratives for distant, British audiences.16 The ‘cheque shirts’ and ‘plaid trowsers’ revealed progress made on the road to civilisation. Short concluded that ‘There is now a small body of trained Christian natives, the nucleus of the native Church.’17

This first group of Aboriginal converts was frequently compared with aristocratic young upper-class Englishmen — especially on the sporting field. Six months after the group baptism, in February 1854, Sam (Conwillan), ‘Sam junior’ and Charlie were in Adelaide, and were invited to play cricket with the pupils of St Peters College, also founded by Short.18 The Adelaide Register reported that ‘The Port Lincoln natives from Archdeacon Hale’s establishment are very fine fellows. They speak pure English, without the slightest dash of vulgarism and are in truth far more gentlemanly than many.’19 Short often praised their refined behaviour and principles of Christian fellowship expressed through the noble game of cricket.20 During this visit, Hale sent two star pupils, Samuel Conwillan (also Kandwillan) and Nannultera to have their portraits painted in Adelaide by John Crossland.21 These well-known works are statements of the achievements and standing of their sitters. The young Nannultera holds his cricket bat aloft, poised and graceful. Samuel Conwillan calmly poses with a book, a sign of his important role within the mission community as catechist, responsible (in the absence of the missionary) for the congregation’s spiritual welfare (Figure 3).

Short and Hale also commissioned photographic evidence of their success, which has survived in the form of their recently rediscovered collections in England. Several of these portraits were treasured by Hale until the end of his life, including five early photographs that are very similar to Crossland’s painting. They express the significance assigned to this group from 1853 by the Anglican leaders Short and Hale as evidence for the mission’s success and a more generalised capacity for Indigenous civilisation and Christianisation.

FIGURE 3: JM Crossland. Portrait of Samuel Kandwillan, a pupil of the natives’ training institution, Poonindie, South Australia [picture]. Oil on canvas, 1854. Rex Nan Kivell Collection NK6294, National Library of Australia, Canberra.

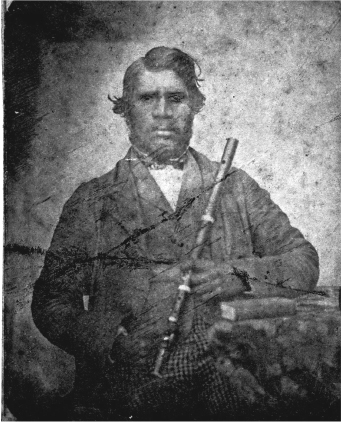

FIGURE 4: Aboriginal man of Poonindie. Ambrotype. With the permission of Special Collections, University of Bristol Library, Papers of Mathew Blagden Hale, DM130/239.

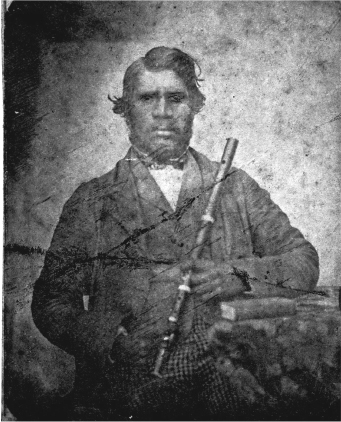

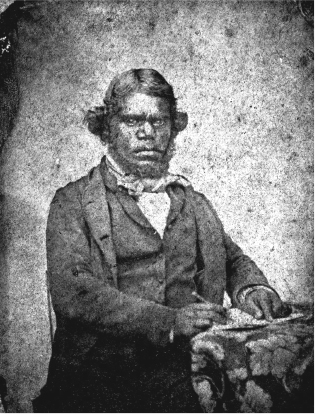

These two remarkable portraits (Figures 4 and 5) are ambrotypes, a technique invented in 1851 that produced a positive image on glass and was very quickly taken up in Australia after 1854.22 If these portraits were made before 1860, when Samuel Conwillan died, one is likely to portray him, as he was one of the most highly regarded Aborigines at Poonindie in the early years.23 He was often mentioned as a committed Christian and leader of his community, and the story was often told how:

The natives were moral in their conduct, and able to resist temptation when sent with drayloads into Port Lincoln. It is remembered how ‘Conwillan’ on one occasion having loaded his own dray with goods from a coasting vessel according to orders, was found by the Archdeacon rendering the like service to a settler, whose teamster was lying intoxicated on the beach.24

FIGURE 5: Aboriginal man of Poonindie. Ambrotype. With the permission of Special Collections, University of Bristol Library, Papers of Mathew Blagden Hale, DM130/238.

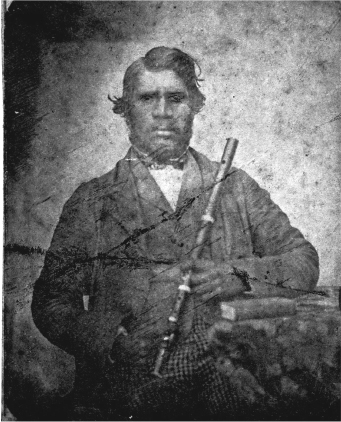

FIGURE 6: Aboriginal man of Poonindie holding a flute. Copy of? daguerreotype. With the permission of Special Collections, University of Bristol Library, Papers of Mathew Blagden Hale, DM130/241.

A further Bristol portrait shows a man holding a flute (Figure 6 and see figure 7).25 This might portray either Conwillan or Tolbonco (also Tolbonko), of whom in 1858 one of the mission trustees, Rev Hawkes, noted:

My old friends Konwillan [Conwillan] and Tolbonco (of St. John’s Sunday school) knew me at once, and appeared glad to see me. They always lead the hymns with their flutes: both of these young men read and conduct the services of our church by turns on Sunday morning, when Mr. Hammond is absent celebrating divine service at St Thomas’s, Port Lincoln.26

We now know that other Poonindie portraits were collected by Poonindie’s missionaries. Octavius Hammond, superintendent at Poonindie between 1856 and 1868, left behind photographic portraits of well-dressed, carefully posed subjects that emphasise their dignity and successful adoption of European civilisation (for example, Figure 8).27 Octavius Hammond must have known almost all the residents of Poonindie throughout the mission’s life. Like Hale’s collection, the portraits suggest a personal relationship with the subjects, and were kept in a personal, domestic context as mementoes of known individuals rather than circulated among a public audience.

FIGURE 7: Aboriginal man of Poonindie. Copy of? daguerreotype. With the permission of Special Collections, University of Bristol Library, Papers of Mathew Blagden Hale, DM130/240.

FIGURE 8: Aboriginal man. Daguerreotype. Mill Cottage Museum Collection, Port Lincoln.

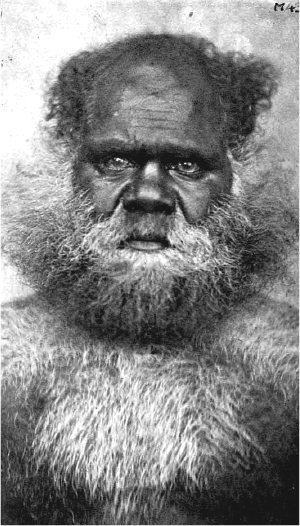

Another eleven South Australian photographs are held by the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, apparently collected by Bishop Short. While having some elements in common with Hale’s Bristol collection, as an entity this series constitutes a classic visual conversion narrative, generated by juxtaposing images of Indigenous people leading a traditional way of life with those who have adopted a Western lifestyle. Seven images show Indigenous people wearing kangaroo skins and bearing elaborate cicatrises. They form a powerful contrast with four studio portraits, including a portrait of Poonindie man James Wanganeen, and three that were commissioned to demonstrate the work of lay missionary Christina Smith, who established an Aborigines’ Home and school at Mount Gambier between 1865 and 1867, under Short’s sponsorship. For Short, photographs were a tool that served to shape understandings of the people the missions aimed to reform, and to document his achievements in the field.

It is significant that all three of the missionaries collected portraits of James Wanganeen, both alone and with his third wife, Mary Jane, which expressed his status within the community. Wanganeen was a Maraura man from the Upper Murray who had attended the Native School in Adelaide in the late 1840s and was then transferred to Poonindie in 1850. He was baptised in 1861, after Hale’s departure, and during the 1860s rose to prominence as an evangelist among his own people.28 The Reverend F Slaney Poole later recalled that ‘One of the members of the choir, named Wanganeen, was a handsome and intelligent aborigine, and he used to read the service on occasions when the superintendent or myself was not present’.29

FIGURE 9: Townsend Duryea. James and Mary Jane Wanganeen. Carte de visite, c. 1867–70/1. With the permission of Special Collections, University of Bristol Library, Papers of Mathew Blagden Hale, DM130/231.

Today, descendants such as Lynnette Wanganeen, James’ granddaughter, have long studied the family history, trying to imagine what he looked like. Lynnette was thrilled to be able to see him through his photographs. With Elva Wanganeen, they have circulated copies around the family, along with the information uncovered by research.

When Short visited Poonindie in 1872, he reaffirmed his belief that ‘the like feelings [of]…Etonians and Harrovians at the cricket matches at Lord’s prov[e] incontestably that the Anglican aristocracy of England and the “noble savage” who ran wild in the Australian woods are linked together in one brotherhood of blood’.30 Ultimately, however, the Indigenous people of Poonindie experienced the contradiction between idealising missionary rhetoric and actual colonial practice: by the 1880s a more authoritarian regime led to increasing disputes between the residents and mission staff, and some longstanding residents were expelled from the mission as a result.31 Under increasing pressure from nearby white settlers who coveted the large area of fertile land leased by the Poonindie trustees, the Anglican Church surrendered their leases in 1894 and the area was opened up for subdivision.32 Only one Poonindie man, Emanuel Solomon, was successful in gaining one of the blocks.33 Most of the other residents, some who had been at Poonindie for more than forty years, were transferred to Point McLeay or Point Pearce missions. A few others remained on Eyre Peninsula, some working for white farmers, while others, particularly local Pangkala and Nauo people, drifted into fringe camps at Port Lincoln or other nearby settlements. Sadly, the missionaries’ imagined future for the Indigenous residents of Poonindie was never realised.

1860S: GROWING CIRCULATION

By the 1860s photographs of Aboriginal people began to assume significant commercial value, due to their growing scientific and popular interest and technological developments such as the invention of the carte de visite around 1860. In the wake of social evolutionism, an interest emerged in recording the supposedly disappearing race. The established Adelaide photographers — ‘Professor’ Robert Hall, Townsend Duryea, Bernard Goode and Henry Davis’ Adelaide Photographic Company — began to compete for the popular market locally and abroad.

One entrepreneur was Noah Shreeve, in 1864 a ‘Commission salesman, storekeeper and importer of fancy goods’ in Weymouth Street, who published a guide for emigrants titled A short history of South Australia, because, as he explained, ‘many are coming; and with the experience I have shown, I might be a little guide to them’.34 Shreeve described the ‘native blacks’, focusing on those he knew personally who lived in Adelaide, whose ‘chief work is horse-breaking, in which they are very good, excellent riders, and very active.’35 He commented, ‘In the month of April, many of them come down from different parts of the north country’36 and this yearly visit seems to have been a good opportunity for Adelaide’s rival photographers to record the interesting visitors. Over the following month several notices of images available were advertised: for example, on 3 May the South Australian Register announced that

We have had an opportunity of seeing a number of well-executed photographs of several aborigines, male and female, whose faces are not unfamiliar to the people of Adelaide. The artist is Mr. B. Goode, of Rundle-street who, we think, has been very successful in his efforts to catch the features, expression, and general appearance of the blackfellows, their lubras, and piccaninnies. It is interesting to have correct representations of a race which seems to be fast disappearing from this land.37

Clearly, these images were seen to have commercial value, and later in 1864 Shreeve registered twelve portraits with the Copyright Office in London (where he had also entered his book), including some of Bernard Goode’s portraits.38 By 1865 the Adelaide Photographic Institution claimed in its advertisements to have 4000 cartes de visite portraits for ‘18s per dozen’, and an album of ‘city views and Aboriginal portraits, 10s per dozen, assorted’.39 Portrait commissions were also carried out by official request for international exhibitions, such as London in 1861, William Barlow’s series at Point McLeay for Paris in 1866,40 and London again in 1873.41 Such representations often stressed the difference of their subjects by showing them naked or partially undressed, despite their altered lifestyle.

NGARRINDJERI AND POINT MCLEAY MISSION

The Ngarrindjeri form an Aboriginal nation of eighteen language groups who inhabit the Lower Murray, Coorong and Lakes area of South Australia. Their lands and waters extended thirty kilometres up the Murray from Lake Alexandrina, the length of the Coorong and along the coastal area to Encounter Bay. They were much photographed from the early 1860s, providing a rich resource for descendants — as Karen Hughes and Ellen Trevorrow explore in the following chapter.42 Many resided at Point McLeay Mission (renamed Raukkan in 1982) after its establishment on their traditional country in 1859 by the Aborigines’ Friends Association and missionary George Taplin.43

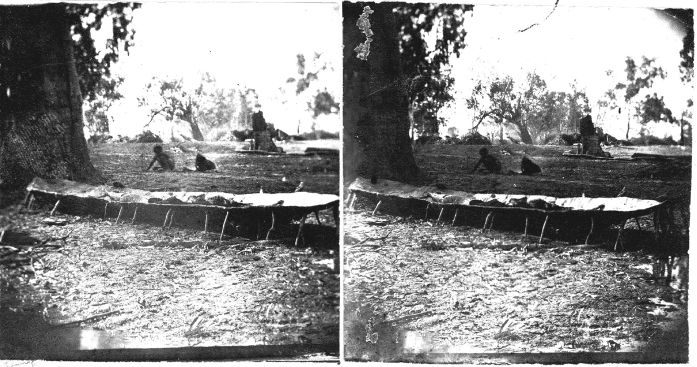

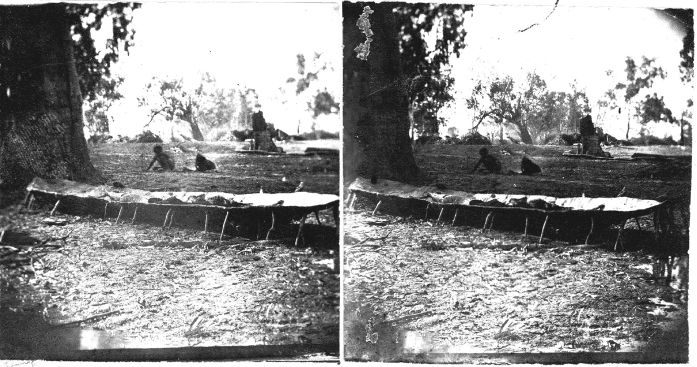

FIGURE 10: George Burnell. Aboriginal canoe building. Stereograph, 1862. State Library of South Australia, B12659.

In 1862 George Burnell and EW Cole travelled from Echuca down the Murray River in a small boat, taking stereoscopic portraits of settlers and Aboriginal people en route, as well as views of landscapes and the flora and fauna. Burnell took some photographs at the Yelta Mission in Victoria and at least three photographs of Aboriginal people along the Murray River in South Australia.44 As Philip Jones points out, these show Indigenous people in context, unlike later ‘isolating’ views.45 One remarkable image shows Aboriginal people making a bark canoe on the lower Murray (Figure 10).

Burnell and Cole arrived in Point McLeay in May and stayed several days (Burnell was Taplin’s brother-in-law). They took a number of photographs of the people and the mission during that time.46 Burnell subsequently offered for sale in Adelaide boxed sets of fifty-six Stereoscopic views of the River Murray.47 In January 1868 Barlow returned to Point McLeay and put on a show of ‘dissolving views’, a technique in which two lanterns projected on to the same spot dissolved seamlessly from one image to the next.48 It is easy to imagine the Ngarrindjeri enjoying such a display of Burnell’s river journey series, which, as Ken Orchard notes, ‘succinctly recapitulates the narrative flow of a river journey’, ending with their own home.49

Point McLeay has remained home to many Ngarrindjeri into the present. In December 1874, 161 people were living at the mission, including those working on neighbouring stations.50 Around 350 other Ngarrindjeri people worked on distant farms and stations, while some continued to lead a nomadic life, moving between the ration depots on the lower Murray and the fringe camps that developed at Goolwa, Victor Harbor, Murray Bridge, Strathalbyn and other towns in the region.51 Although Taplin had strongly opposed many traditional customs in his early days, by the 1870s he was carefully recording cultural information, which he published in an ethnographic study, The Narrinyeri (1874), and in The folklore, manners, customs and languages of the South Australian Aborigines (1879).52 Duryea’s composite photograph of five oval portraits (four Ngarrindjeri men and one woman) was used as the frontispiece for The Narrinyeri.53 Such accounts circulated in the context of social evolutionism, in which images and information about Aboriginal culture had become scientific evidence for their biological difference. Popular notions of biological difference only strengthened over the last decades of the nineteenth century, distancing these photographic subjects from their own lives and experiences.

In 1911 the South Australian Parliament passed the Aborigines Act 1911, which established the Aborigines Department with the Chief Protector as its head. The new Act gave the Chief Protector wide powers over most aspects of the lives of Aboriginal (i.e. ‘full-blood’) and ‘half-caste’ people throughout the state. In 1913 an inquiry into the reserves and missions recommended their transfer to the control of the Aborigines Department, under state control.54 When the Aboriginal Lands Trust Act 1966 (SA) was proclaimed, all reserves in South Australia were vested in the Aboriginal Lands Trust.

Doreen Kartinyeri’s mother, Thelma Rigney, who grew up on Raukkan, had ‘a lot of photos of the family stuck on the wall. There was a lovely one of her grandmother, Mutyuli, and old James Rankine, who used to work together at Poltalloch in the late 1800s.’55 She remembers that tourists were a constant presence:

The Protector let white people come in and see the way Aboriginal people lived. Buses would go from Adelaide to Goolwa for the ferry tours regularly through the summer, and forty or fifty people would come into Raukkan on the boat. The visitors took a lot of photographs, and sometimes they would send a copy back to Raukkan school. The steamer had been coming into Raukkan from back in the late 1800s, and I’ve got photographs showing all the little girls wearing white aprons over their school clothes. I remember my Aunty Rosie saying she got sick of having to dress up in a little white pinnie every time the steamer came in. I don’t know whether those people thought that’s what people on the mission wore all the time.56

As the following chapter explores, Ngarrindjeri and other Aboriginal people took their own photographs or acquired images of themselves that they continue to value as an important heritage resource into the present.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Cynthia Hunter and the Ngaut Ngaut Mannum Aboriginal Community Association. We also acknowledge Tom Gara, whose research report has been of great value in preparing this overview.

NOTES

1. ‘Aborigines of South Australia’, Illustrated London News, 14 February 1846, p. 108.

2. Now held by the Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford. This print was almost certainly made from a glass negative, and was perhaps copied from an even earlier daguerreotype. Already a well-known figure to colonists, his portrait was painted by Hermann Schrauder in 1851, and subsequent engraved versions continued to circulate over following decades. For extended discussion, see S Braithwaite, T Gara & J Lydon, ‘From Moorundie to Buckingham Palace: images of “King” Tenberry and his son Warrulan, 1845–55’, Journal of Australian Studies, 35(2):165–84, 2011.

3. P Brock & D Kartinyeri, Poonindie: the rise and destruction of an Aboriginal agricultural community, Aboriginal Heritage Branch and SA Government Printer, Adelaide, 1989, p. 2.

4. T Gara, ‘Survey of nineteenth century photographs of Aboriginal people in South Australia’, unpublished report for Aboriginal Visual Histories project, Monash University, 2010; P Jones, ‘Ethnographic photography in South Australia’ in J Robinson assisted by M Zagala (eds), A century in focus: South Australian photography 1840s–1940s, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 2007, pp. 102–7.

5. The photograph was probably taken either at Port Lincoln or at one of the Mortlock pastoral properties on Eyre Peninsula by an unknown photographer. J Messenger, ‘Daguerreotype portraits, 1840s – c. 1860’ in Robinson assisted by Zagala (eds), above n 4, pp. 28–9.

6. These portraits are held in the Ayers House Collection in Adelaide, donated in September 1979, all catalogue 4a: accession 0787, Jacky — now known as Master Mortlock, and 0784, Jemima and W.T. Mortlock. Taken about 1859. Same person. A missing portrait, 0783, Wife of Jacky — Known as Master Mortlock — 1855, presumably formed a pair with Jackey’s portrait, and was perhaps made in 1855.

7. His name had been placed on the West Torrens electoral roll by a Mr Paxson, seemingly as a joke, but following testimony from Mortlock, the Court of Revision retained his name; ‘Court of Revision — West Torrens’, South Australian Register, 15 July 1854, p. 2; ‘The native “Jackey”’, Sydney Morning Herald, ‘Extracts from the South Australian Register: something new’, 5 August 1854, p. 3.

8. Pastoral pioneers of South Australia, vol. 1, Publishers Limited Printers, Adelaide, 1925, p. 93.

9. Chief Secretary’s Office no. 819 61/59, from AJ Murray, Government Resident, Port Lincoln 26/1859, cited in Brock & Kartinyeri, above n 3, p. 7.

10. Chief Secretary’s Office no. 819 61/59, from AJ Murray, Government Resident, Port Lincoln 26/1859, cited in Brock & Kartinyeri, above n 3, p. 8.

11. The Resident noted that the evidence showed that Colotoney was already very ill with a lung complaint and was not in a fit state to be shepherding sheep in the first place, let alone to be beaten and kicked for failing to do so; Chief Secretary’s Office no. 819 61/59, from AJ Murray, Government Resident, Port Lincoln 26/1859, cited in Brock & Kartinyeri, above n 3, p. 8.

12. For an extended discussion focusing on Hale’s series held in Bristol, see J Lydon & S Braithwaite, ‘“Cheque shirts” and “plaid trowsers”: photographing Poonindie Mission, South Australia’, Journal of Anthropological Society of South Australia, Special Issue: Aboriginal Missions 37: 1–30 Dec 2013; also J Lydon and S Braithwaite ‘Photographing “the nucleus of the native church” at Poonindie Mission, South Australia’, Photography and Culture, forthcoming 2014.

13. Brock & Kartinyeri, above n 3, pp. 3–4; P Brock, Outback ghettos: a history of Aboriginal institutionalisation and survival, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1993, p. 24.

14. Augustus Short, ‘The Poonindie Mission, described in a letter from the Lord Bishop of Adelaide to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel’, Missions to the Heathen, no. xxv, Diocese of Adelaide, South Australia, printed for the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, London, 1853, pp. 17–18; also, ‘The native mission at Port Lincoln’, South Australian Register (Adelaide), 14 March 1853, p. 3; at that time there were fiftyfour residents, including eleven married couples, the rest children (including thirteen from the Port Lincoln district). Most of these names were also listed by George Wollaston (son of Archdeacon Wollaston), who spent part of 1852 managing Poonindie Mission Station; when he departed in February 1852 he was presented with a book and a letter signed by fifteen Aboriginal elders (original residents): Nytchie, Nwrouny, Mannere, Kandwillan, Popjoy, Bidpowie, Kewerie (or Keurrie), Mudlong, Tootko, Pathera, Kadlingare, Yarrioke, Tartwin, Coordinga and Friday. This momentous event took place a decade before the feted conversion of Wotjoballuk man Nathaniel Pepper at the Moravian-run Ebenezer Mission in north-western Victoria.

15. Short, above n 14, pp. 17–18.

16. The literature on this genre is now wide ranging, and addresses examples and processes usually in regional terms. See, for example, P Jenkins, ‘The earliest generation of missionary photographers in West Africa’, Visual Anthropology, 7:115–45, 1994; V Webb, ‘Three missionary photographers in the Pacific: divine light’, History of Photography, 21(1):12–22, 1997; KT Long, ‘“Cameras never lie”: the role of photography in telling the story of American Evangelical missions’, Church History, 72(4):820–51, 2003. Short and Hale were diligent in reporting progress to their financial supporters in the form of popular accounts written for a wide audience — especially for the senior missionary societies of the Church of England, The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts and the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge, which had sponsored Poonindie.

17. Short, ‘The Poonindie Mission’, above n 14, pp. 17–18. In his book The Aborigines of Australia, Hale later noted that ‘We held regular evening service at sundown; and after the second lesson I baptized Thomas Nytchie, James Nurrung, Samuel Conwillan, Joseph Mudlong and Martha Tanda, wife of Conwillan’, MB Hale, The Aborigines of Australia: being an account of the institution for their education at Poonindie, in South Australia: founded in 1850 by the Ven. Archdeacon Hale, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London, 1889. Both Short and Hale claim to have baptised the converts.

18. This boarding school for colonial youth was not dissimilar from the mission in its aims and approach, which Short described in 1853 as ‘educating their minds, shaping their characters, and making their souls Christian’. Named after Short’s own former school, The Royal College of St Peter in Westminster, it was seemingly established along similar lines as Poonindie in 1847; K Thornton, The messages of its walls & fields, a history of St Peter’s College, 1847 to 2009, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2010, viewed 8 August 2012, <www.stpeters.sa.edu.au/#history>.

19. The Register, 7 February 1854; see discussion in J Daly, ‘“Civilising” the Aborigines: cricket at Poonindie, 1850–1890’, Sporting Traditions: The Journal of the Australian Society for Sports History, 10(2):59–68, 1994.

20. Short, above n 14, pp. 19–20.

21. J Tregenza, ‘Two notable portraits of South Australian Aborigines’, Journal of the Historical Society of South Australia, 12: 22–31, 1984.

22. J Cato, The story of the camera in Australia, Institute of Australian Photography, Hong Kong, 1979; A Davies & P Stanbury, The mechanical eye in Australia, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1985.

23. Brock & Kartinyeri, above n 3, p. 16.

24. A Short, A visit to Poonindie, and some accounts of that mission to the Aborigines of South Australia, Adelaide, 1872, p. 8.

25. These are seemingly copies of daguerreotypes or ambrotypes and were taken during the same studio session, as indicated by their identical setting, pose and clothing.

26. GW Hawkes, ‘Poonindie Mission’, South Australian Register, 28 September 1858, p. 3.

27. Six daguerreotypes and ambrotypes were rediscovered in November 2011 by Pauline Cockrill, Community History Officer with History SA, at Mill Cottage, a house museum at Port Lincoln, built for storekeeper Joseph Kemp Bishop, son of John Bishop, one of the district’s first settlers and a trustee of Poonindie. Joseph married Elizabeth Hammond, Octavius’ daughter, in 1868.

28. Brock & Kartinyeri, above n 3. In 1864 he travelled to the Ngarrindjeri with Rev. BT Craig, Missionary Chaplain for the Bishop of Adelaide, and in 1865 with James Unaipon, William Kropinyeri and Harry Tripp; George Taplin, South Australian Museum, carbon copy diary kept by Rev. George Taplin, AA 319/11/4, 1 January 1963 – 2 August 1865.

29. ‘An interesting career’, The Register, 1 September 1921, p. 7; PA Howell, ‘Poole, Frederic Slaney (1845–1936)’, Australian dictionary of biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, viewed 7 November 2013, <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/poole-frederic-slaney-8075>.

30. Augustus Short, 1871, quoted in Hale, above n 17, p. 100.

31. Brock, above n 13, pp. 50–1.

32. C Raynes, A little flour and a few blankets: an administrative history of Aboriginal affairs in South Australia 1834–2000, State Records SA, 2002, p. 28; see also J Raftery, Not part of the public: non-Indigenous policies and practices and the health of Indigenous South Australians 1836–1973, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2006, pp. 108–9.

33. Brock, above n 13, pp. 55–6.

34. Noah Shreeve, A short history of South Australia, printed for the author, London, 1864, p. 40, viewed 7 November 2013, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.aus-vn4695455>.

35. ibid.

36. ibid.

37. ‘Photography’, South Australian Register, 3 May 1864, p. 2.

38. Photographs of Aboriginal people registered at the Copyright Office in November 1864 held in the Public Record Office, London, National Archives, copy 1/7.

39. ‘Adelaide Photographic Institution’, South Australian Advertiser, 12 September 1865, p. 1.

40. RJ Noye, Dictionary of South Australian photography, 1845–1915, Art Gallery of South Australia, 2007 (CD attached to Robinson assisted by Zagala (eds), above n 4), p. 35.

41. A list of items to be sent to the Great Exhibition in London in 1861 included some ‘photographs of natives’; Advertiser, 26 October 1861, p. 2; Advertiser, 28 February 1873, p. 7, cited in Gara, above n 4, p. 6.

42. See Philip Jones’ excellent overview in Robinson assisted by Zagala (eds), above n 4.

43. G Jenkin, Conquest of the Ngarrindjeri: the story of the Lower Murray lakes tribes, Rigby, Adelaide, 1985, pp. 78–9.

44. One of Burnell’s photographs taken at Yelta Mission is in the State Library of South Australia (PRG 1258/2/2365).

45. Jones, above n 4, p. 105.

46. Noye, above n 40, p. 59.

47. K Orchard, ‘George Burnell 1830–1894’ in Robinson assisted by Zagala (eds), above n 4, p. 68.

48. Jones, above n 4, p. 104.

49. Orchard, above n 47, p. 68; see also K Orchard, ‘Regional botany in mid-nineteenth century Australia: Mueller’s Murray River collecting network’, Historical Records of Australian Science, 11(3): 389–405, 1997.

50. Report of the Sub-Protector of Aborigines for half-year ending 31 December 1874, Aborigines’ Office, Adelaide, 1874, viewed 15 November 2013, <http://archive.aiatsis.gov.au/removeprotect/59891.pdf>.

51. R Foster, ‘Tommy Walker walk up here…’ in J Simpson & L Hercus (eds), History in portraits, Aboriginal History Monograph no. 6, 1998, pp. 195–7; Report of the Sub-Protector of Aborigines for half-year ending 31 December 1875.

52. G Taplin, The Narrinyeri: an account of the tribes of South Australian Aborigines inhabiting the country around the Lakes Alexandrina, Albert, and Coorong, and the lower part of the River Murray: their manners and customs, also, an account of the mission at Port Macleay, JT Shawyer, Adelaide, 1874; G Taplin (ed.), The folklore, manners, customs, and languages of the South Australian Aborigines/gathered from inquiries made by authority of South Australian Government, E Spiller, Acting Government Printer, Adelaide, 1879.

53. Noye, above n 40, p. 105, fn 399; see also Jones, above n 4, p. 105.

54. Raynes, above n 32, pp. 36–9.

55. D Kartinyeri & S Anderson, Doreen Kartinyeri: my Ngarrindjeri calling, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2008, p. 5.

56. ibid., pp. 16–17.