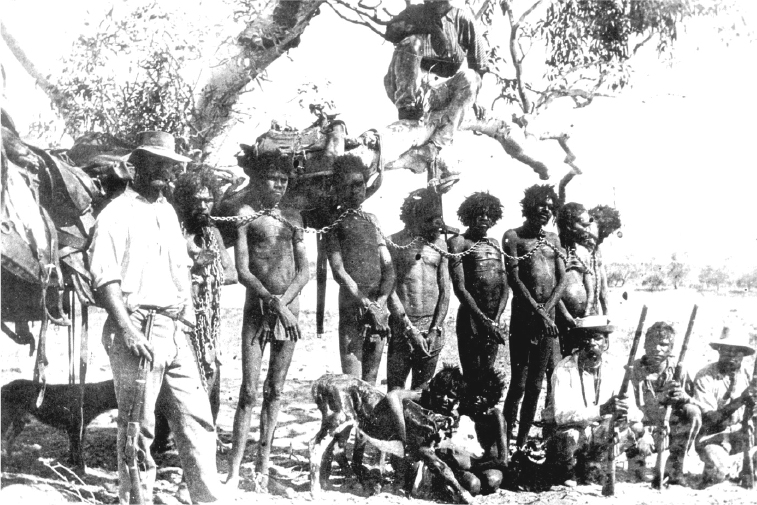

FIGURE 1: Aboriginal prisoners in chains, posed with a policeman and Aboriginal trackers [picture], c. 1890. Photo-print. State Library of Western Australia, Perth, Call number 7816B.

PHOTOGRAPHING ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS IN WEST AUSTRALIA

Donna Oxenham

Throughout Western Australia’s history — almost from its first days of British settlement to the present day — Aboriginal people’s lives have been recorded by photography. The reasons behind collections vary, from an individual’s fascination with a race of people who were presumed at the time to be ‘dying out’ to an attempt by government bodies to prove that their treatment of Aboriginal people was the right one — a quest to indoctrinate and educate, bringing them out of their ‘savage’ pre-existence into a more civilised lifestyle. Today, however, descendants and relatives of the photographic subjects give the photographs a range of very different meanings, as this chapter explores. But to initially give these photographic collections context I felt it was important to provide a brief history of Western Australia’s settler – Aboriginal relations.

British settlers established themselves on the south-western shores of Western Australia in 1829 with the intention of creating a new settlement; the Swan River Colony.1 Historian Neville Green suggests that:

the early contact between the European settlers and the Aborigines had been relatively uneventful. The reports and journals of the early settlers suggest that the invasion was initially peaceful because the Aborigines believed the white men were the returning spirits or re-incarnates of their own dead.2

As a result, the Noongar people — whose land they found themselves upon — took it upon themselves to care for the colonialists. An excerpt from the Perth Gazette in 1833 quotes settler RM Lyon:

[T]he Aboriginal inhabitants of this Country, are a harmless, liberal kind hearted race; remarkably simple in all their manners. They not only abstained from all acts of hostility, when we took possession; but showed us every kindness in their power. Though we were invaders of their country, and they therefore a right to treat us as enemies, when any of us lost ourselves in the bush, and were thus completely in their power; these noble minded people shared with us their scanty and precarious meal; suffered us to rest for the night in their camp; and, in the morning directed us on our way to head quarters, or to some other part of the settlement.3

Thus, the growing colony in Western Australia was composed of several types of people. On the one hand, there were altruistic individuals who believed that Aboriginal people could be saved from the chains of slavery and ultimate demise by ‘civilising’ them, in a European sense. Conversely, there were others with entrenched Eurocentric, paternalistic views, who maintained that the Aboriginal people were beyond help — the lowest of creatures, who should be treated as such. Because the Western Australian settlement was a free-settler colony, it did not have the luxury of relying upon convict labour to build infrastructure or to add to the settlement’s numbers, so from 1829 to 1850 settlers relied quite heavily on the aid of the local Indigenous groups for their survival. As a consequence, a relationship of sorts was formed during the early stages of station homesteads and pastoral leases throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century, as settlers acquired the bush expertise of the Indigenous people.

However, the arrival of convicts to Western Australia as a labour force in 1850 changed what was an already strained relationship and increased the rift in Indigenous–settler relations. Green suggests that:

the arrival of convicts provided an alternative source of cheap labour and a lessening of interest in training Aborigines for menial tasks. The responsibility for taming and training passed from the priest and the school teacher to the magistrate and the prison warder.4

By 1868, 10,000 convicts had arrived in Western Australia. Any chance of Aboriginal people developing a reasonable working relationship and viable economic future with the colony was destroyed with the establishment of a penal workforce.

FIGURE 1: Aboriginal prisoners in chains, posed with a policeman and Aboriginal trackers [picture], c. 1890. Photo-print. State Library of Western Australia, Perth, Call number 7816B.

Also, during the early years of the growing colony, white men initially outnumbered the women by four to one,5 so it was only a matter of time before colonial men began to lure impoverished Aboriginal women into the illegal profession of prostitution. Some Aboriginal tribes offered their women in a ceremonial exchange that signified hospitality or diplomacy.6 However, more often than not these exchanges were violent transgressions against Aboriginal women. The short-term effects of these ‘exchanges’ were devastating for both Aboriginal men and women. Not only did the men lose their women, but many lost their lives in retribution against the settlers for the violence often committed or the venereal diseases inflicted upon their people.7 Also, the absence of contraception meant that a growing population of mixed-descent children was being produced.

As time passed, the Aboriginal population fell increasingly under the control of the white authorities, and the ongoing expansion of the colony resulted in the continued dispossession and cultural desecration of the Indigenous people and forced relocations into settlements that were usually established on the outskirts of towns.

However, a continued Aboriginal resistance hindered development into further so-called ‘free-lands’. As a result, the settlers enlisted the aid of the military forces as an additional method of control. The colonial government even recruited a select number of Aboriginal men to fill positions of authority and power as native constables and trackers, in order to ‘utilise them in controlling their Aborigines’ (Figure 1).8

Any retaliation in response to colonial expansion was depicted as criminal behaviour. One particular historical event, which marks an ominous stain in Western Australian history, occurred in 1834. It would become known as the ‘Pinjarra Massacre’ or the ‘Battle of Pinjarra’, where more than eighty Pinjarup people were killed as a result of settler requests for military protection.9 Consequently, the relationship between colonists and Indigenous people in Western Australia during this period not only foreshadowed what was to come later, but also the context in which the Aboriginal peoples’ fate would be worked out. Over time, Aboriginal people learned what it meant to be ‘Aboriginal’ through the eyes of the imperialist settler state. Accordingly, they suffered the immediate and violent impacts of colonisation and bore the full effects of governmental policies of control over Indigenous people.

The law, the church and the missions each developed policies to govern Aboriginal people. In 1904 a Royal Commission conducted by Walter Roth, the Chief Protector of the Aboriginal people in Queensland, into the condition of the Western Australian Aboriginal people led to the passage of the 1905 Aborigines Act (WA). Hence, the Aborigines Department became a fully fledged government department under the control of the Chief Protector. Although its stated aim was to ‘make provision for the better protection and care of the Aboriginal inhabitants of Western Australia’, it soon became apparent that the administrators’ intentions were to serve the interests of settler society, and they did more to hinder the Aboriginal people than to assist. The Act allowed for total paternalistic control of every aspect of Aboriginal people’s lives.

By powers vested under the Act, the Chief Protector had the power to manage the property of Noongar people, with or without their consent, and his approval was required before an Aboriginal marriage could go ahead.10 In this way, the law regulated Aboriginal people so that they were segregated from the wider community and placed on reserves and missions, except when their services were required. Indeed, the Act gave Honorary Protectors permission to enter Aboriginal camps at any time, and to remove them from towns arbitrarily.

The Native Administration Act 1936 (WA) extended the powers of the 1905 Aborigines Act and gave the Department of Native Affairs unprecedented power over the daily lives of West Australian Aboriginal people. Section 12 enabled the Minister to cause the removal of Aboriginal people from any place to a reserve, district, institution or hospital. No judicial process was involved and there was no mechanism for appeal. Under Section 8, the Commissioner was given rights over all Aboriginal minors under twenty-one years of age.

Toussaint argues that the 1936 Act’s underlying principle was the ultimate absorption — biological, social and cultural — of even those Aboriginal people who had escaped the effect of the 1905 Act.11 Almost a decade later, the Native (Citizens Rights) Act 1944 (WA) was found to be just as intrusive in Aboriginal people’s lives, and Hodson suggests that in the late 1940s state intervention changed to reflect a new belief that Aboriginality was the result of social environmental influences, rather than heredity influences.12 This attitude saw the creation of the certificate of citizenship, which allowed Aboriginal people to be recognised as Australian citizens. This, however, did not give Aboriginal people the right to vote as Australian citizens. Among other intrusions, it also demanded of those that obtained a citizenship certificate that they denounce their Aboriginal heritage and culture, to convince the courts that they were ‘moral citizens’. They were subjected to medical tests to verify that they did not suffer from venereal disease, and they had to demonstrate that they had had no ‘native’ or ‘tribal’ associations for two years prior to their citizenship application. This control led to the eventual degradation of a highly spiritual people.

THE MISSION ERA

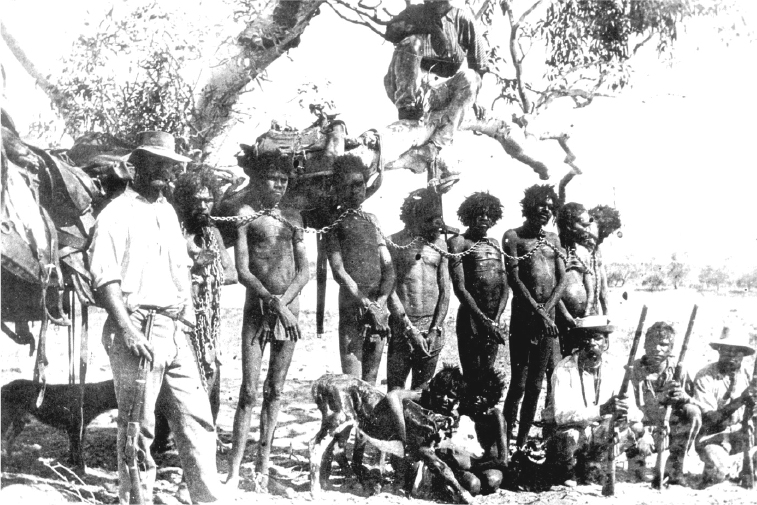

Many missions became an important tool in the south-west to implement these legislative policies and to further facilitate the dispossession, both physical and spiritual, of Aboriginal people. With the perceptions of the time depicting Aboriginal people as heathens (possessing no morals in the wider society), the missionaries purported to fill the supposed moral vacuum and were instrumental in the attempted cultural genocide against the majority of Aboriginal people.

The missions imposed an alternative way of life upon the younger generations of Aboriginal communities by breaking down strict customs and traditions of which all of the older generations were knowledgeable. The elderly Aboriginal people were separated from the youths of their own clans and were unable to pass on their knowledge and traditions.13 Missionaries and philanthropists took it as their duty to improve Aboriginal society by teaching them Western ways, and were instrumental in breaking down cultural traditions that had been practised by Aboriginal people for centuries. However, this did not stop Aboriginal elders from continuing their traditions and holding corroborees within the mission system.

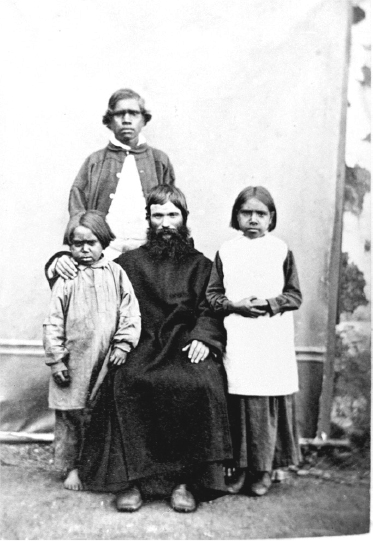

FIGURE 2: Roebuck Bay natives, Beagle Bay Mission, c. 1895–1910. State Library of Western Australia, Perth, BA1344/96.

Missionaries worked mainly with the children, who were not old enough to fully understand the laws of their people, and re-educated them to the Christian faith and the laws of European society. The institutions set up to receive Aboriginal people under the Western Australian legislative Acts soon became overcrowded holding centres and were ill-managed, cramped and unhealthy. Jack Davis, Aboriginal poet, playwright and activist, who spent time at Moore River Settlement in 1932, recalls that it ‘suffered from bad administration and lack of funds…and that the dormitory crawled with bugs and fleas, while the dining room and the cook house were crawling with cockroaches’.14 Although administrators depicted Moore River and other settlements as places where the inmates settled ‘down to a new life of peace, contentment and usefulness’, they were, in fact, horrid, dirty and unhygienic places.15 The mission life experienced by many Aboriginal peoples varied across the state from one institution to another, but ultimately they were used to irrevocably change a way of life that had been practised for centuries prior to the arrival of settlers.

FIGURE 3: An Aboriginal family [picture], 1890–99. State Library of Western Australia, Perth, 2893B/100.

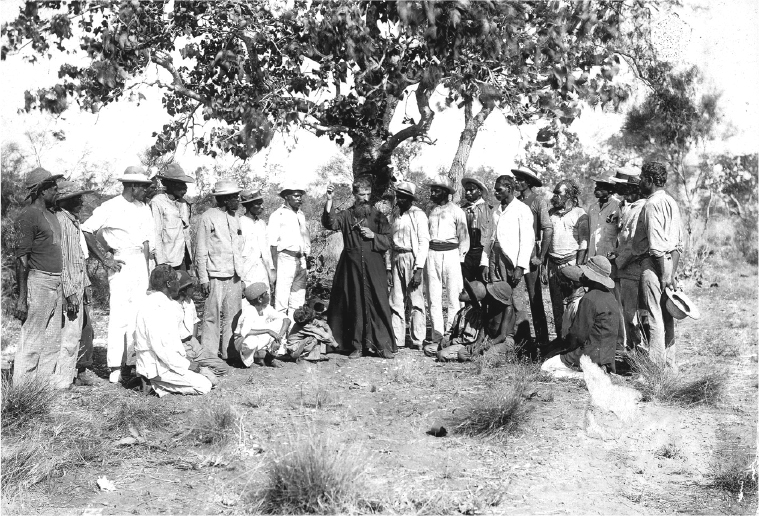

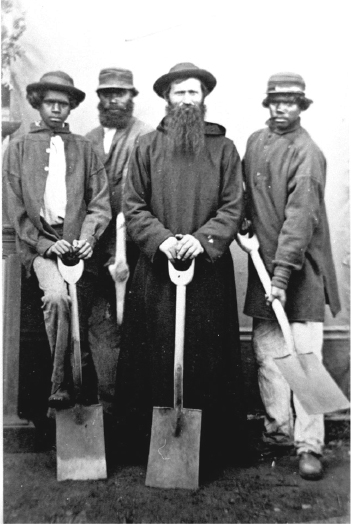

FIGURE 4: [Three Aboriginal males and a priest holding shovels], New Norcia, 1860. Berndt Museum, Crawley, #7506.

One photographer, in particular, to photograph changes brought about by missionary interventions was William Pearce Clifton (1816–85). Clifton, a Western Australian amateur photographer, farmer and magistrate, extensively photographed Fremantle during this time period and is considered to be among the best photographers of the town at that time.16 Along with his parents and fourteen siblings, the Cliftons were the first settlers to establish themselves in the Australind region of the south-west of Western Australia, arriving in 1841. Clifton was appointed the agent for claims to the Western Australian Land Company in 1846, and was a significant landholder and pastoralist in the region, holding office as a Justice of the Peace and Resident Magistrate for Bunbury.17 Over the years that followed, the Clifton family was actively involved in the establishment and management of the Church of St Nicholas, Australind.

FIGURE 5: [Studio shot of two girls in long white dresses and hats], New Norcia, 1860, Berndt Museum, Crawley, #7508.

FIGURE 6: [A seated priest, two small children standing either side and an aboriginal adult standing behind], 1860. Berndt Museum, Crawley, #7500.

It was during this time, however, that Clifton took a particular interest in Aboriginal studio portraits. These striking images were taken around 1860 and concentrated specifically on the Aboriginal people who were placed with, or voluntarily resided at, the New Norcia Monastery, which was established in 1846 by Spanish Benedictine missionaries. Led by Bishop Rosendo Salvado (1814–1900), the mission’s aim was to ‘civilise and evangelise according to the European ideals of the time, but [Salvado] did so with sympathy for indigenous culture that was rare in his day’.18

What is interesting to note is the transition or contrast between Clifton’s ‘traditional’ images, in which the Aboriginal subjects were photographed in their ‘native’ dress with nature backdrops (Figure 3), as opposed to his images of Aboriginal subjects post their arrival at the mission. The later images emphasise the monastery’s influence on the lifestyle of its Aboriginal inhabitants. No longer were they clothed in their traditional garb, but donned Western-style clothing and had seemingly adapted or integrated Western beliefs and customs.

Clifton’s intent in recording these images is unknown, as there has been very little information found apart from his public duties. Whether it was from personal curiosity or his belief in the duties of a public officer to record Aboriginal people, the images show the progression and assimilation of the Aboriginal occupants in their attempts to accommodate a lifestyle that was socially acceptable to European sensibilities. Figures 4, 5 and 6 represent this transition.

State government control over all aspects of Aboriginal people’s lives continued until 1967, when the Commonwealth was given the power to make laws in respect to Aboriginal people following the 1967 referendum.

A HISTORY OF WEST AUSTRALIAN PHOTOGRAPHY

Photography draws much of its power from its indexicality, the chemical trace of light reflected off the physical reality in front of the camera. It is this tracing of Indigenous lives that constitutes the enormous potency and political impact of the symbolic sucking of a life force for source communities. Through this process, photographs translate the flow of lived experiences into a series of stilled, muted fragments of space and time, defying diachronic connections and separating the image from its real-life subjects.19

Photographers were rare during the early years of settlement in Perth; although there are records of photographers travelling to Perth for short periods of time, many were not primarily focused on recording images of the local Aboriginal people. The colonisation of Western Australia was not a peaceful venture and resulted in many Aboriginal people and nations losing their lives and territories, and the ensuing resistance turned Aboriginal people into society’s outcasts. They were labelled ‘a dying race’, and, as a result, many photographers became interested in capturing ‘the natives’ in their primal state. Some felt the need to document the changes during the assimilation era, as those who could not adhere to Western ideals were rounded up into missions, prisons and jails, and treated like criminals. Many of these early photographs have been lost over time, but some remain. These collections are now of great significance to Aboriginal people, who see beyond the chains and derogatory captions to the people, places of significance and country that encapsulate who they are as a people today.

The following discussion is a brief look at a few photographers who recorded Aboriginal people throughout the state. Due to the west’s small population, photographers were often attracted to the larger populations of the east. As a result, the first photographs in Western Australia were made fifteen years after its European settlement, but by the 1860s there were solid amateur and professional practices in most settled areas. Photo historian Gael Newton suggests that by ‘1860 some 100 photographers were at work and another 100 or so had practiced for some time since 1841’.20

Robert Hall (c. 1821–1866), a publican based in Adelaide, was the first photographer to visit the Swan River Colony at Perth in November 1846, but only a few poor examples of his work have survived.21 A number of American daguerreotype photographers arrived during the 1850s and set up some of the leading studios of the next few decades. One of the earliest was Samuel Evans, who arrived in Western Australia in 1853 and set up his Daguerrean Gallery, first at Fremantle, then Perth. Not many examples of Evans’ daguerreotypes have been identified, although a good scattering of daguerreotype portraits and one view of a Perth street exist in Western Australian collections.22

Townsend Duryea (1823–1888) arrived in Melbourne from New York in 1852 as an experienced professional photographer and formed a studio partnership with Alexander McDonald in Bourke Street. He later relocated to Adelaide in 1855 to form ‘Duryea Brothers’ with his brother Sanford between 1855 and 1859. From this base they toured the regional towns, and paid several visits to Perth, setting up a studio for four to five weeks at a time, and Sanford briefly established a Perth studio from 1857–59.23 According to Noye, Townsend’s career:

as a photographer was cut short when his studio and entire collection of 50,000 negatives were destroyed by fire on 18 April 1875. This loss was a serious blow to Duryea and historians alike, as the plates were the best record of early South Australian colonial life ever made.24

This would also account for the lack of archival photographs to be found in Western Australia.

As a result, photography did not make much of a permanent appearance in Western Australia until Greenham & Evans established the first studio in Perth in the 1870s. Even though the studio’s works varied across a broad range of topics and subjects, it did touch upon photographing Western Australian Aboriginal people.

The carte de visite was not used in Australia until Sydney photographer William Hetzer, working between 1850 and 1867, introduced it in 1860. The new style of miniature visiting card portraits was cheaper than daguerreotypes and sets of a dozen were sold for approximately 15 shillings in the mid-1860s, which was half the cost of one daguerreotype. One photographer to make use of carte de visite photography was Australian-born John Joseph (JJ) Dwyer.

JJ Dwyer (1869–1928) was born in Gaffney’s Creek, a gold mining town in Victoria, where he spent the first fifteen years of his life. After completing an apprenticeship as a blacksmith, Dwyer’s interest in photography became his passion and eventually his profession. In 1896 he headed westward to the latest goldfields and eventually landed in Kalgoorlie, where he established himself as a professional photographer:

Dwyer was a prolific photographer who appeared to delight in his occupation, exploiting every available commercial avenue. His photographs appeared in the Kalgoorlie Weekly, and the Western Argus, he entered competitions, and he had a selection of his photographs published as postcards.25

Although the majority of Dwyer’s work concentrated on the growing social life and the expanding infrastructure of the booming mining town, he did make a point of documenting the lives of the Aboriginal inhabitants of the area:

At the time there was also considerable interest in documenting indigenous people. In Australia, papers read at meetings of the scientific community urged listeners to document ‘the passing of the Aborigine’ and the expedition of Baldwin Spencer and Gillen to the Northern Territory in 1901 aroused considerable curiosity. As a man of his times Dwyer made his contributions, taking many shots of Aboriginal people, in his studio and in their own setting.26

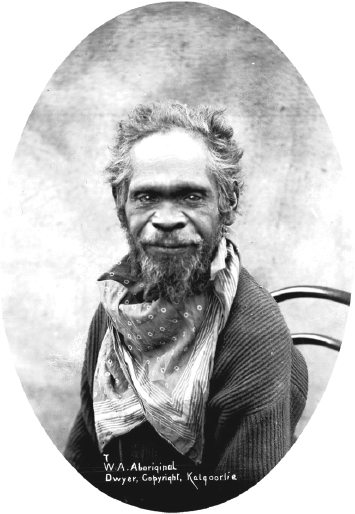

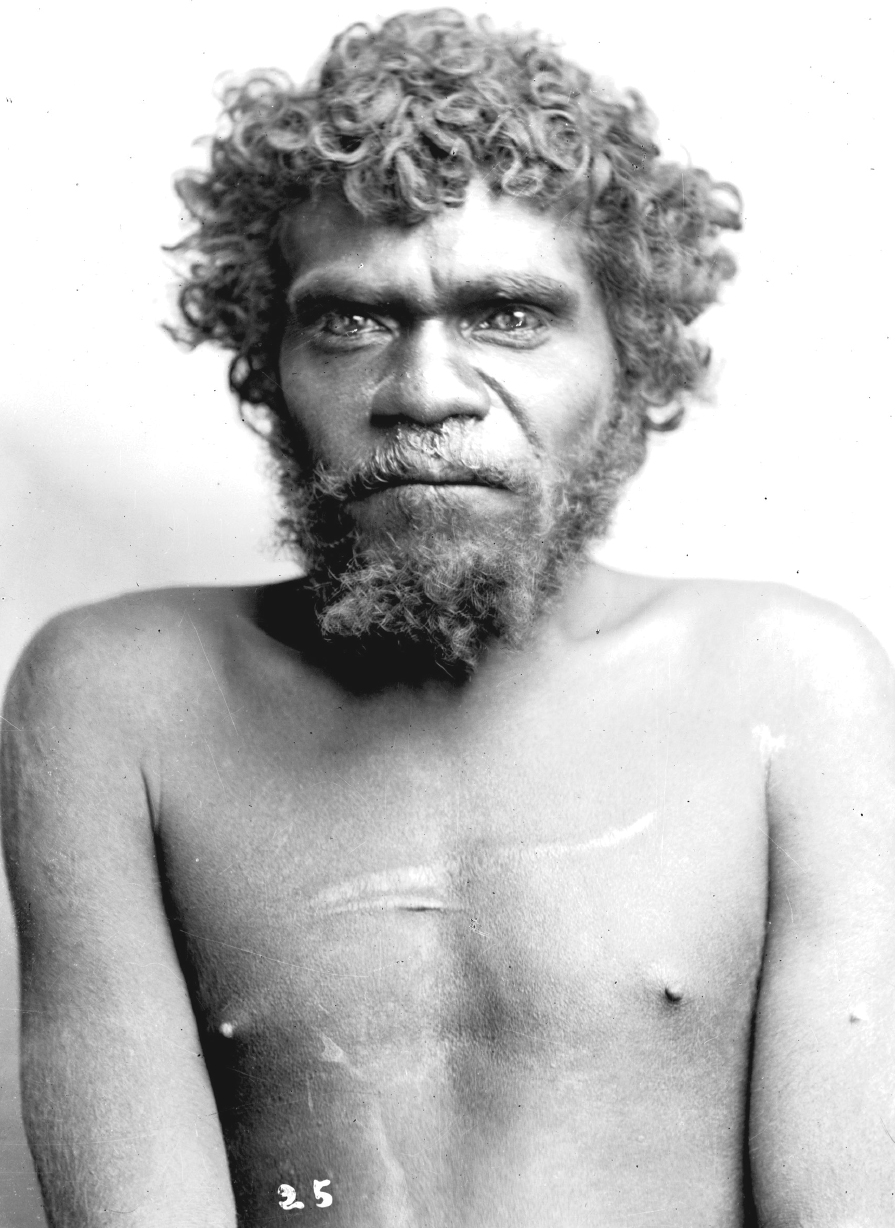

As a result, there are a few examples of Dwyer’s work that he had produced as postcards (Figures 7 and 8).

Dwyer’s collection, housed within the Library and Information Service of Western Australia, consists of 578 photographs and chiefly chronicles his journeys overseas and in the eastern states. The collection also has a series of images of mine workings and Aboriginal people in Kalgoorlie, taken between 1900 and 1928. Dwyer varied his photographic themes over the years, from the studio-based portrait shots to Aboriginal people in their natural environment. What is interesting to note is that Dwyer was renowned for his ability to retouch a photograph so as to ‘take twenty years off one’s age, as he employed retouchers, generally women with a delicate touch, who removed blemishes and wrinkles from the portrait but left “character lines” in’.27 He did not employ these techniques when photographing Aboriginal people, choosing to capture them in their ‘natural state’. We can see this from portrait shots that were taken in his studio (Figures 9 and 10).

FIGURE 7: JJ Dwyer. The belle of Kanowna [picture], c. 189–. State Library of Western Australia, Perth, 8292B/B/180.

FIGURE 8: JJ Dwyer. W.A. Aboriginal [picture], c. 1900. State Library of Western Australia, Perth, 8292B/B/181.

Such portraits are symbolic in the sense that they represent a more documentary or scientific approach to capturing the subjects’ essence. Dwyer chose to encapsulate them in a way that places them in the category of ‘other’ — removed from the ‘civilized and now’ and located as the ‘uncultured and ancient’.

FIGURE 9: JJ Dwyer. An Aboriginal man of the Kalgoorlie region [picture], c. 1900. State Library of Western Australia, Perth, 8292B/B/138.

FIGURE 10: JJ Dwyer. Aboriginal man, Kalgoorlie [picture], c. 1900. State Library of Western Australia, 8292B/B/186.

MAJOR COLLECTIONS AND HOLDING PLACES FOR PHOTOGRAPHIC ARCHIVES IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA

BATTYE LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA

The Battye Library’s pictorial collection has more than one million images. Its intended aim is to depict all facets of Western Australian social history. However, at present only 10 per cent of the collection is available in a digital format to online users. For those wishing to view the majority of photographic images available, it is necessary to visit the library in person.

It is important to note that categories such as ‘Indigenous/Aboriginal Photographic Collections’ have been spread out over different categories according to how, when and by whom they were donated. In many situations photographic collections have been donated without information attached to each image, so many photographs have simply been recorded as ‘unidentified Aboriginal’. Also, many items in the pictorial and film collections contain images of, or depict, secret/sacred content (the display of which may cause sadness and distress), so they have been removed from the index card catalogue, as well as the photographic volumes.

In saying this, however, the Battye has made tremendous progress with its Aboriginal collections in terms of making the archival collections more accessible to the public. In particular, efforts to return Aboriginal photographs and other materials directly to Aboriginal families, communities and peoples through the new Storylines project launched in 2013 will be, in my opinion, the benchmark for other archival institutions across Australia to follow.

BERNDT MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY

The Berndt Museum of Anthropology is housed within The University of Western Australia. Its primary collections were donated to the museum in 1976 by its founders, Ronald M Berndt and Catherine H Berndt — both successful anthropologists who worked extensively with Aboriginal communities within Western Australia and beyond.

The museum contains one of the largest collections of items from within Australia. Of particular interest are the photographic collections, which house more than 35,000 images — 15,000 of which relate to Western Australia’s past. These images have been sourced from government, mission settlements and pastoral stations. Of the vast photographic materials, two collections of particular interest to Indigenous people are the RM and CH Berndt Collection and the AO Neville Collection.

FIGURE 11: Moore River Native Settlement [Nurse with two infants. Matron with two infants, possibly twins], n.d. AO Neville Collection, Berndt Museum, Crawley, #7692.

The AO Neville Collection was assembled by this influential official in order to support his arguments for management of Western Australia’s Indigenous people and, especially, their assimilation. Henry Prinsep, the first Chief Protector for Western Australia, had aimed for separation, supporting segregation because he was ‘convinced that the improvement of the Aborigines’ lot (and protection of the wider society) was to be achieved by limiting Aborigines’ contact with the white settlement and, where necessary, by removing them from society altogether’.28 However, the appointment of Auber Octavius Neville (1875–1954) as Chief Protector in 1915 introduced what would become known as an era of degradation, assimilation and cultural genocide — not only for Noongar people, but for West Australian Aboriginal people in general. Indeed, the consequences of that era are still felt in the Aboriginal community today. It is significant that Neville was an avid believer in documenting all aspects of the assimilation process. As a result, he compiled a vast collection of photographs to help justify the removal of Aboriginal people to missions and pastoral stations throughout the state.

FIGURE 12: Moore River Native Settlement [Row of children standing in front of the kindergarten teacher], 1936. Berndt Museum, Crawley, #697.

ANTHROPOLOGY DEPARTMENT PHOTOGRAPHIC COLLECTION WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM

The Western Australian Museum, established in 1891, has been collecting images of Indigenous people since 1899. Many of the early collections were donated by private sources, but there are also more recent collections.

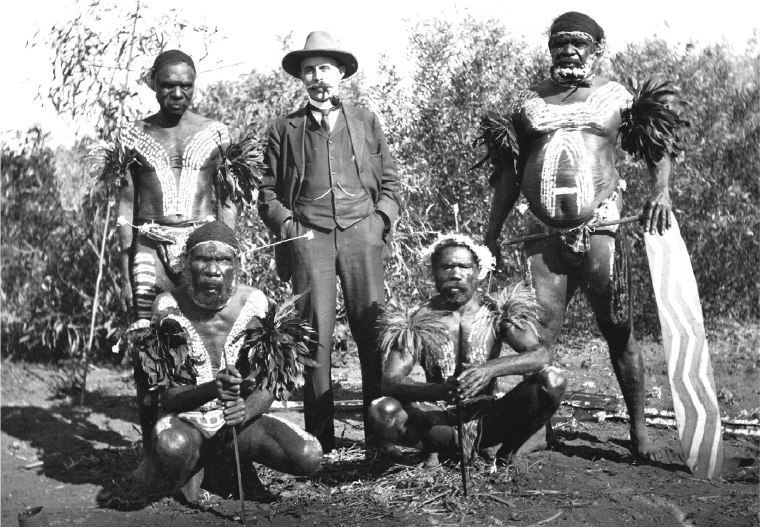

The museum currently holds around a hundred photographs taken during the early 1900s by Ernest Lund Mitchell (1876–1959) in various regions throughout Western Australia. Mitchell was a successful photographer who dominated the Western Australian commercial and official markets from 1909 until the late 1920s:

Mitchell’s photographs are a rich source of ethnographic information as they show clear details of artefacts such as shields, spears, boomerangs and headdresses. They provide cultural information for those with knowledge of its interpretation, though Mitchell himself did not record this information on his negatives or prints. The tone of his captions and their pictorial style suggest that they were not taken with anthropological intent, nor were they created as part of exhibitions, and most circulate outside the strict discourse of anthropology. In spite of not being created specifically to produce anthropological information, the photographs contain features which have made them attractive for anthropological uses almost from the time they were taken.29

FIGURE 13: EL Mitchell. Aboriginal men in traditional dress with man in suit [picture], c. 1920–30. State Library of Western Australia, Perth, BA1271/162.

Although originally commercial in nature, Mitchell’s Indigenous photographic collections are an important source for Aboriginal people today.

INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES AND REPATRIATION PROJECTS

Visual repatriation is, in many ways, about finding a present for historical photographs, realising their potential to seed a number of narratives through which to make sense of the past in the present and make it fulfill the needs of the present.30

Traditionally, Aboriginal people recorded their history orally and were able to keep alive the memories of loved ones and the knowledge of country without the necessity of the written word or archival record. Since colonisation, however, people’s oral histories in many places have become fragmented. Therefore, with access to relevant photographic collections, Indigenous people and communities today are able to amalgamate the archival images with their oral histories. As a result, the concept of time becomes somewhat inconsequential, and the past, present and future co-exist. Not only do they depict images of people’s ancestors, their country and places of significance, but they become ‘living entities’ in their own right — able to remove themselves from the spectrum of time and the Western concept of ‘the past’ and place themselves within the ‘here and now’.

Through access to these images, we, as Indigenous people, are able to come full circle — what was then has become the now. For many, finding and receiving images of one’s ancestors may be the only link to the past. It is especially relevant for members of the Stolen Generations, who were forcibly removed from their families and cultural heritage. Thus, they are able to begin a healing process and find — for want of a better term — an ‘end in the beginning’.

Historically, Indigenous interaction with institutions like museums and State Government-run libraries and departments has been limited and one-sided. In many cases, Indigenous people became the objects and subject of archival collections — albeit collected and archived through the eyes of the non-Indigenous outsider. When dealing with photographic archives, Edwards suggests that:

[P]hotographs are amongst the most potent of museum objects. In cross-cultural terms they have an enormous and two-fold potential. They are an evidential source within the communities they depict, inscribing complex layers of cultural information and knowledge, and an important site of negotiation for the development of long-term collaborative relations between museums and communities.31

Overall, through allowing Aboriginal communities greater agency and access to these archives, the process of reconciling aspects of the past can begin. With Aboriginal people now looking back at these institutions through the looking glass (so to speak), the relationship between institutions and Aboriginal people can be based upon more equal footing.

In Western Australia a number of avenues are available to Aboriginal communities wishing to obtain copies of photographic collections housed within the archival institutions. The majority of these institutions allow individuals or communities to come in, source relevant materials, and then apply to have copies produced and sent to them. This is usually done at cost price, as most institutions do not have a budget allocation to allow for the repatriation of photographic materials to Aboriginal communities and/or individuals.

However, two institutions in Western Australia that have been instrumental in repatriating copies of visual collections back to Aboriginal communities throughout the state are the Berndt Museum of Anthropology and the State Library of Western Australia. Not only have they begun actively repatriating historical Aboriginal photographic collections, but they have begun the process of digitising and repatriating their extensive sound collections.

The Berndt Museum has, to an extent, been funded to facilitate this process, thus making it easier for Aboriginal communities to receive relevant images and collections of their forebears without the financial costs normally associated with producing copies of images as found in other institutions.

Originally an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission-funded endeavour, the Bringing the Photographs Home project — officially launched in 2000 — was designed in response to the Bringing them home report, which focused on reconciliation and aided the healing process for the Stolen Generations. As stated on the museum’s website:

The Stolen Generation deserves the opportunity for people to reconnect to their families, even if it is only in photographic form. Sometimes, a photograph is the only record of their forebears. Not only is it important for the older generations to identify their family history, but it is also crucial that this information is passed to younger generations, which is imperative for reclaiming and forming identity.32

As a result, a number of repatriation projects have been successfully undertaken by the Berndt Museum throughout Western Australia. For example, in 2000 the museum’s archives relating to Goulburn Island were repatriated back to the Warruwi people, and the local Community School acted as a repository. In this instance, the museum was able to hand back a collection of 300 photographic images, as well as sound recordings. Other repatriation projects have since been co-ordinated, with various cultural centres and Aboriginal Land Council representative bodies throughout the state acting as holding centres for the returned materials.

The State Library of Western Australia Storylines pilot project, I believe, will change the way institutions deal with their archival collections relating to Aboriginal peoples. This interactive program (which is based upon the Ara Irititja software platform) has the potential to revolutionise the way photographic, audio and other recordings are repatriated back to the Aboriginal families, communities and peoples from which they came. The Storylines database currently holds 1500 photographs from the library’s heritage collections, 1600 people have been identified within these records, and 168 places such as stations, missions, landmarks and towns have been identified.

RESEARCH PROJECTS

Finally, the Australian Research Council-funded project Globalisation, Photography and Race: The Circulation and Return of Aboriginal Photographs in Europe, based at The University of Western Australia, is currently working to return photographs to Aboriginal people. The project has four key European museums as partners — the University of Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum, the Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, the Musée du quai Branly in Paris and the Volkenkunde (National Museum for Ethnology) in Leiden. Using digital technology, these collections are being analysed and collated with the aim of returning them to relatives and descendants. The ability to use technology to repatriate archival collections to Aboriginal peoples is not only a sign of the times, but an important tool that Aboriginal people can use to bring their ancestors from the past and place them firmly within the present.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Because of the complexities involved with the repatriation of historical photographic collections to Aboriginal communities, it is fundamental that the process of returning photographic materials is handled in a culturally appropriate manner — and it is important to fully understand the significance these compilations represent for Indigenous people. It is often said that a photograph can speak a thousand words, but for Indigenous people these archival images represent so much more:

[P]hotographs are ultimately uncontainable; they carry an incompleteness and unknowability. There is seldom a ‘correct interpretation’: one can say what a photograph is not, but not absolutely what it is. Consequently, meanings emerge that are perhaps diametrically opposed to, for instance, colonial intentions of the photographs.33

Thus, through Indigenous eyes not only do these photographic collections depict images of people’s ancestors, their country and places of significance, they also become ‘living entities’ in their own right, assuming an independent existence in the present. By recording their histories within an oral tradition, Indigenous people were able to keep alive the memories of loved ones and the knowledge of country. Now, with access to relevant visual archives, Indigenous people and communities today are able to amalgamate the visual image with their oral stories and histories. Western ideas of linear time are undermined, and past, present and future are conflated.

These images are an integral part of an age-old tradition and culture that cannot be supplanted by what outsiders’ perceptions of Aboriginal people were at the time of taking a photograph. These collections today are welcomed by the majority of Aboriginal people, who see these records as evidence of their survival and strength, not as depictions of a ‘dying race’ or the colonised. Consequently, images of Aboriginal people being chained and treated like criminals, for example, are relatively inconsequential to Aboriginal people today. Like the chains that once bound Aboriginal prisoners together, these historical photographic collections bind Aboriginal people to their past.

What is important is the people, places of significance and country that can be found within these images. In my opinion, Aboriginal people are rather forgiving of the past and although some images — and sometimes the captions that go with these images — are distressing, what becomes important is the ability to tangibly hold these photographs of our past, which can reinforce our cultural foundations rather than destabilise them.

The photographic archive is a powerful source of information for Aboriginal people. In each image we see where we’ve been and in turn what we’ve become. They are ‘living’ proof that Aboriginal people are survivors and that our culture has survived through tremendous adversity.

NOTES

1. The King George Sound settlement was established three years earlier and much further south in what was to become known as Albany as a British military outpost intended to forestall any plans by France for settlement in Western Australia.

2. N Green, Nyungar, the people: Aboriginal customs in the southwest of Australia, Creative Research in association with Mount Lawley College, Perth, 1979.

3. RM Lyon quoted in Green, above n 2, p. 148.

4. N Green, ‘Aborigines and white settlers in the nineteenth century’ in CT Stannage (ed.), A new history of Western Australia, University of Western Australia Press, Perth, 1981, p. 93.

5. C Mattingly & K Hampton, Survival in our own land: Aboriginal experience in ‘South Australia’ since 1836: told by Nungas and others, Hodder and Stoughton, Sydney, 1988, p. 174.

6. H Reynolds, The other side of the frontier, Penguin Books, Ringwood, Vic., 1981, p. 70.

7. AJ Barker & M Laurie, Excellent connections: a history of Bunbury, Western Australia, 1836–1990, City of Bunbury, Bunbury, WA, 1992, p. 10.

8. MC Howard, ‘Aboriginal Australia in south-western Australia’ in RM Berndt & CH Berndt (eds), Aborigines of the west: their past and their present, University of Western Australia Press, Perth, 1980, p. 58.

9. D Horton, The encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 1994, p. 111.

10. A Haebich, For their own good: Aborigines and government in the southwest of Western Australia, 1900–1940, University of Western Australia Press, Nedlands, WA, 1988, p. 85.

11. S Toussaint, ‘Nyungars in the city: a study of policy, power and identity’, unpublished Masters thesis, University of Western Australia, Perth, 1987, p. 65.

12. S Hodson, ‘Nyungars and work: Aboriginal labour in the Great Southern Region, Western Australia 1936–1972’, unpublished Masters thesis, University of Western Australia, Perth, 1989, p. 137.

13. AR Radcliffe-Brown in H Reynolds (ed.), The other side of the frontier, Penguin Books, Ringwood, Vic., 1981, p. 135.

14. J Davis, A boy’s life, Magabala Books Aboriginal Corporation, Broome, WA, 1991.

15. GC Bolton, ‘Black and white after 1897’ in Stannage (ed.), above n 4, p. 144.

16. ‘William Pearce Clifton’, Design and Art Australia, viewed 11 November 2013, <www.daao.org.au/main/anniversary?date%5Bmonth%5D=5&date%5Bday%5D=1>.

17. In 1840 the Western Australian Land Company was formed in London with the purpose of promoting a large land settlement scheme in the Colony of Western Australia. This was planned by a group of influential men, including William Hutt MP (brother of John Hutt, Governor of Western Australia from 1838 to 1846) and Edward Gibbon Wakefield, upon whose principles of colonisation the company was founded. Marshall Waller Clifton (William Pearce Clifton’s father) was appointed Chief Commissioner and his son Robert Williams Clifton (1817–1897) was appointed secretary to Waller; ‘Marshall Clifton’, Wikipedia, viewed 11 November 2013, <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marshall_Clifton>.

18. ‘The Salvado era: 1846–1900’, New Norcia Benedictine Community, viewed 11 November 2013, <www.newnorcia.wa.edu.au/protectinga-unique-heritage/the-story-of-new-norcia/the-salvado-era.html>.

19. E Edwards, ‘Introduction: locked in the archive’ in L Peers & AK Brown (eds), Museums and source communities: a Routledge reader, Routledge, London, 2003, p. 84.

20. G Newton, ‘Chapter three: extending the franchise’ in Shades of light: online (based on text from the original book Shades of light: photography and Australia 1839–1988, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1988), viewed 11 November 2013, <www.photo-web.com.au/ShadesofLight/03-franchise.htm>.

21. ibid.

22. ibid.

23. ibid.

24. RJ Noye, ‘Duryea, Townsend (1823–1888)’, Australian dictionary of biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, viewed 11 November 2013, <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/duryeatownsend-3458/text5283>.

25. R Pascoe & F Thompson, In old Kalgoorlie, Western Australian Museum, Perth, 1989, p. 11.

26. ibid., p. 7.

27. ibid.

28. Aboriginal Legal Service, Telling our story: a report by the Aboriginal Legal Service of Western Australia (Inc) on the removal of Aboriginal children from their families in Western Australia, Aboriginal Legal Service, Perth, 1995, p. 11.

29. J Sassoon, ‘Becoming anthropological: a cultural biography of EL Mitchell’s photographs of Aboriginal people’, Aboriginal History, 28:59–86, 2004, p. 65.

30. Edwards, above n 19, p. 84.

31. ibid., p. 83.

32. ‘Projects involving the Berndt Museum’, Berndt Museum of Anthropology, The University of Western Australia, viewed 12 November 2013, <www.berndt.uwa.edu.au/generic.lasso?token_value=projects&menu=1>.

33. Edwards, above n 19, p. 84.