At 9:20 A.M., November 30, 1939, the first Russian plane appeared over Helsinki. It dropped thousands of leaflets urging the citizens to overthrow the Mannerheim/Cajander/Erkko government, then went on to drop five light bombs in the general vicinity of Malmi Airport.

As dawn gave way to full daylight, the morning sky was bright and clear, except to the south, where a large cloud bank had formed in the direction of Estonia. At about 10:30, the forward edge of those clouds suddenly rippled with light as a wedge of nine Russian planes (SB-2 medium bombers) left cover and leveled off for a run over the capital. The leading aircraft released their first sticks of bombs over the harbor, presumably aiming at the shipping crowded there. All of the bombs fell harmlessly into the water.

Then the formation banked toward the downtown heart of the city, apparently aiming at the architecturally renowned Helsinki railroad station. Although there was no resistance and weather conditions were ideal, the Russians didn’t manage to get a single hit on the station itself. They did, however, thoroughly plaster the huge public square in front of the building, killing forty civilians.

Three planes peeled off and raked the municipal airport, setting fire to one hangar. The Helsinki Technical Institute was badly hit, and several students and faculty were killed. The Russian formation then broke into small groups, and these roamed at will above the city, scattering random bundles of small incendiary bombs, doing little serious damage but causing a chaotic rash of small fires that stretched the city’s fire-fighting resources to the limit. On their way out, the planes took time to strafe a complex of working-class housing units and to drop their last few high-explosive bombs on the inner city, some of which severely damaged the front of the Soviet Legation building.

Then the bombers throttled for altitude, formed into a neat formation again, and flew off to the east, the empty sky behind them dotted with a few puffs of smoke as Helsinki’s antiaircraft batteries clawed after them in vain. None of the flak batteries had opened fire until the last moments of the raid, and not one of their shells came within 1,000 meters of an enemy aircraft. Not until the Red bombers had vanished did the city’s air-raid sirens belatedly start to howl their now-pointless warning.

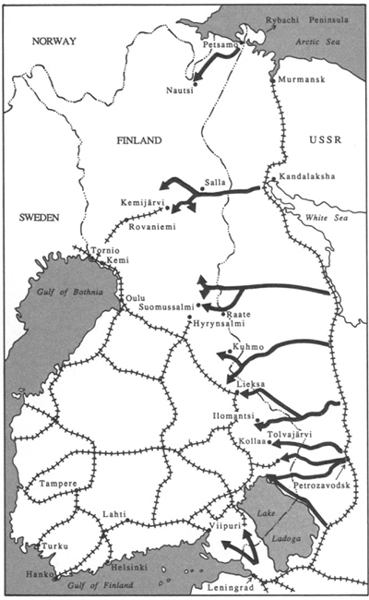

2. Major Soviet Offensives of November 30-December 1

Another raid, this time by fifteen planes, struck at about 2:30 P.M., after the all-clear had sounded and while the streets were choked with civilian and emergency traffic. Most of the bombs fell at random, but another fifty people died and two or three times as many were injured. All told, Helsinki suffered 200 dead that first day.

On the same morning the Red Air Force launched heavy attacks on Viipuri, on the harbor at Turku, on the giant hydroelectric plant at Imatra, and—for some inexplicable reason—on a small gas mask factory in the town of Lahti.

Out in the Gulf of Finland, landing parties from the Soviet Baltic Fleet occupied without resistance the disputed islands of Sieksari, Lavansaari, Tytarsaari, and Suursaari.

After detouring past craters, corpses, and piles of flaming debris, Gustav Mannerheim’s car pulled up to government headquarters. Inside the Marshal sought out President Kallio and withdrew his resignation. Kallio had been expecting him and, on the instant, activated him as commander in chief of the Finnish armed forces.

By the end of the day, the Finnish government had changed hands. The major instrument of that change was the veteran left-center political leader Väinö Tanner, head of the powerful Social Democrats. Tanner spent most of the day huddled in an air-raid shelter, and he emerged from that experience more convinced than ever that the inflexible nationalistic regime of Prime Minister Cajander and Foreign Minister Erkko would have to yield power. Tanner had already lined up the necessary parliamentary support when he approached Cajander that night, after the civilian government had moved to its wartime headquarters at Kauhajoki, northeast of Helsinki.

To soften the emotional blow, Tanner engineered a symbolic vote of confidence for Cajander in the Finnish Diet, then he took Cajander aside and told him that he had two choices: resign now with honor intact, or suffer the historical shame of being booted out of office in the morning. It was a bitter moment for Cajander: he and Erkko had worked hard to lead the nation through several relatively prosperous years, always with considerable public support for their policies. Now they were being pronounced unfit to lead Finland in time of war. Nevertheless, although there was much hard feeling in private, the public changing of the guard was accomplished with grace and dignity on the part of all concerned.

Tanner himself replaced Erkko as foreign minister. To fill Cajander’s place at the prime minister’s desk, Tanner picked Risto Ryti, president of the Bank of Finland. The new government’s policy was clear: to reopen negotiations and end hostilities as fast as possible. To maximize Finland’s bargaining power, the military strategy would be to hold on to every inch of Finnish soil and to inflict maximum casualties on the enemy—to present Stalin with such a butcher’s bill that he, too, would be eager for negotiations.

While Tanner worked the diplomatic front, Ryti ran the war effort, including the campaign to obtain aid from abroad. He worked closely with Marshal Mannerheim, usually at the Marshal’s headquarters rather than the civilian government’s. Mannerheim refused to leave his command post when there was a battlefield crisis to deal with, which, after the first hours of the war, there usually was.

These men became, in effect, a ruling triumvirate. President Kallio and the Diet rubber-stamped their decisions, although sometimes with reluctance. On their sagacity and flexibility, and on Mannerheim’s tactical grip, rested nothing less than the fate of their nation.

The entire Finnish strategy was based on a single reality and a single logical assumption. The reality was that, given the size of its army, Finland could not defend every part of its long border with the USSR. The assumption was that, given the nature of the geography, Finland would not have to.

Only on the Isthmus could a large modern army be sustained in prolonged campaigning. North of Lake Ladoga the only place Mannerheim was really concerned about was the part of Ladoga-Karelia on the north shore of the lake. There, in a fifty-to-sixty-mile-wide corridor, were two good roads that led from the border to the interior. One started at Petrozavodsk, inside Russia, and the other ran from the Murmansk railroad along the rocky coast of Lake Ladoga; the two converged near the village of Kitelä. Just a day’s march beyond Kitelä was a crucial section of Finland’s railroad network, along with good roads leading north and south.

This was, in fact, the “back door” to the Isthmus. The road net would support the movement of large formations, including armor, and it seemed logical for the Russians to make an attempt to break through here, wheel south, and take the Mannerheim Line from the rear.

Anticipating such a Soviet thrust, the Finns had held war games there several times during prewar maneuvers and had come up with a sound plan to deal with it. They would let the Russians come in and advance along the converging roads until they reached a strong line of prepared defenses that ran Lake Ladoga–Kitelä–Lake Syskyjärvi. Once the Russians were pinned down, with their supply lines long, thin, and vulnerable and their left flank up against Ladoga, a strong Finnish counterattack would fall on their right flank from the supposedly impassable wilderness below Loimola and Kollaa, cut off the head of their salient, and methodically destroy it.

Mannerheim and his staff had allocated what seemed like an adequate force for this task: two infantry divisions and three battalions of border troops, all of them about as well equipped as any units in the Finnish Army, organized into the Fourth Corps, under command of Major General Juho Heiskanen.

But the Russian Eighth Army, responsible for the entire Ladoga-Karelia front from Tolvajärvi to Lake Ladoga itself, had some unpleasant surprises in store for the Finns. During the fall a new railroad line had been extended from Eighth Army’s main supply base at Petrozavodsk up to the border, just across from the Finnish town of Suojärvi. This strategic preparation nearly doubled the Russians’ supply capability on this front. When the war broke out, they struck here not with three divisions, the maximum number Mannerheim believed they could sustain, but with five, together with a full brigade of armor. And before the war’s end, they would field in this sector all or major portions of another eight divisions.

Most alarming of all was the attack of two entire divisions up at Suojärvi, a sector where Mannerheim had expected nothing stronger than reconnaissance patrols. In the opening days of the war there was virtually nothing to stop these Soviet units from outflanking the entire Fourth Corps line from the northeast, or from rolling through Tolvajärvi in a westerly thrust and running amok in the interior of Finland. It was a crisis situation from the beginning, and before it was stabilized, Mannerheim would be forced to commit one-third of his entire available reserves, seriously depleting the Finns’ ability to reinforce the defenders of the Isthmus.

When Mannerheim studied his situation maps on the night of December 1, these were the threats he saw developing in Ladoga-Karelia:

1. Against the vulnerable road net at Tolvajärvi, the Russians launched their 139th Division: 20,000 men, under General Beljajev, augmented by 45 tanks and about 150 guns. In that whole critical sector, the Finns could muster at the war’s beginning only 4,200 men. None of them were regular army troops, just border guards and Civic Guard reservists. Supporting this attack was the Russian Fifty-sixth Division, which stormed across at Suojärvi then turned southwest and thrust toward Kollaa, seeking to get behind the main Finnish defensive line north of Lake Ladoga.

2. On the north shore of Ladoga itself the Russian 168th Division under General Bondarev struck at Salmi. The plan called for it to advance to a line that ran from Koirinoja to Kitelä and there join forces with the Eighteenth Division under General Kondrashev, which had attacked along the Uomaa road, parallel to and about twenty miles north of the Ladoga coastal road. The plan evolved so that the Eighteenth soon received orders to turn north toward Syskyjärvi, four miles north of the Lemetti road junction, and attack the Kollaa defense line from the rear at the same time it secured the flank of the 168th Division. Strong Finnish defensive positions kept it from ever posing a real threat to the Kollaa line, however.

Another serious drain on Mannerheim’s reserves were the powerful but isolated thrusts into the forested wilderness of central and northern Finland. North of Fourth Corps’s front, the roads were so few and the terrain so utterly hostile during winter that the Finns had expected no large-scale Russian threats between Kitelä and Petsamo, their arctic toehold at the base of the Rybachi Peninsula. Instead the Russians sent eight full divisions into the forests, heavily supported by armor and artillery.

By the end of December 1, Mannerheim’s maps showed the following threats developing from Petsamo south to Tolvajärvi:

1. At Petsamo the Russian 104th Division attacked by sea and by land, supported by naval gunfire and heavy coastal guns sited on the approaches to Murmansk. The Russian plan called for this division to advance down the Finns’ “Arctic Highway” and capture the Lapland capital of Rovaniemi by December 12. That seemed like a reasonable proposition, since the numerical odds on this front favored the Russians by something like forty-two to one. Two regiments of the Russian 104th Division were added to this force after the initial landings and border crossings.

2. At the tiny Lapp town of Salla a two-pronged thrust was begun by the Eighty-eighth and 122d divisions. Their objective was the town of Kemijärvi, where they could pick up some good roads and from there move quickly against Rovaniemi to the southwest, linking up there with the Petsamo invasion force. The Finns did not think the enemy’s Petsamo force could negotiate the 300 miles of benighted, wind-scoured tundra between Petsamo and Rovaniemi, even if there was nobody shooting at them. Therefore the Salla thrust was considered by far the more serious threat to the Lapland capital.

3. The picturesque little village of Suomussalmi was a target simply because it blocked one side of the narrow “waist” of Finland; and it lay astride the shortest route to Oulu, Finland’s most important port on the Gulf of Bothnia. Roads on the Finnish side of the border were fairly well developed in this region. The attack was opened by the 163d Division, 17,000 strong, and weighted down not only with much armor and mechanized equipment but also with such paraphernalia as brass bands, printing presses, truckloads of propaganda leaflets, and sacks of goodwill gifts, presumably for all the disaffected Finnish workers its troops would encounter in the woods. Although the Soviet political assessment was fantastic in its presumptions, it was not made up entirely out of thin air. Communist agents were known to have been active in the Suomussalmi region, and the voting patterns in national elections indicated considerable popular support for left-wing politicians and policies. Stalin obviously believed the area was ripe for “liberation,” and Mannerheim, at least in the beginning, had some worries along those lines himself. In any event, if the Russians took Suomussalmi, they gained good routes to the railroad junction at Hyrynsalmi. From there, Oulu was only 150 miles away, and if Oulu fell, Finland would be cut in half.

4. The Russian Fifty-fourth Division, led by Major General Gusevski, attacked toward Kuhmo with 12,800 men, 120 pieces of artillery, and 35 tanks. Opposing their advance was a ragtag force of Finnish border guards and reservists numbering about 1,200.

5. Just south of the Kuhmo thrust, the Russian 155th Division attacked toward Lieksa, with 6,500 men, 40 guns, and a dozen tanks. Opposing it were two Finnish battalions, about 3,000 men, and 4 light, obsolete field guns.

While the campaigns on land were gathering momentum, there was a flickering, shadowy naval war going on in the Gulf of Finland and adjacent waters. It was an interesting sideshow, but it did not amount to very much. There were two reasons for that. The first and most obvious is the fact that by the end of December, the Gulf of Finland had started to freeze into a vast sheet of ice. The other reason is that the navies involved did not amount to very much, either.

If there was such a thing as an “elite” force in the Red Navy of 1939, it was the Baltic Fleet—but that was not much of a distinction. The Red Navy was strictly a provincial coast defense force at that time, and technologically it was about a quarter-century behind either the Royal Navy or the German Kriegsmarine. The Baltic Fleet did occupy several of the disputed gulf islands, but these operations were unopposed. It did not have the training, the logistical structure, or the landing craft to undertake large-scale amphibious operations. Nor was it blessed with a commander in chief of strategic vision. Some idea of Stalin’s competence as a naval strategist can be derived from his insistent attempts to persuade his Baltic Fleet commanders to attack Turku harbor with submarines, even though they kept pointing out to him, with words, maps, and aerial photos, that the approaches to that harbor were so shallow and strewn with reefs that no submarine could possibly survive long enough to reach a firing position.

The Finnish Navy, 13,000 men, was strictly a coast defense force. There were a dozen or so modern PT boats, some mine warfare vessels, a number of shallow-draft gunboats (some of them dating back to the tsarist era), four small submarines, and two big ships that could be described as cruisers or monitors, depending on whether one looks at their design or their function. They were named Väinämönen and Ilmarinen, after two popular heroes in the Kalevala, the Finnish national epic, and they had been the pride of the prewar government. They were handsome ships, and for their weight they packed considerable firepower. The one and only English-language description of these ships ever to see print states that their main batteries were 105 mm. guns, but no one ever built a cruiser-sized ship to carry such relatively puny weapons. Extant Finnish photographs clearly show a more powerful battery, and the 1940 edition of Jane’s Fighting Ships confirms that the main guns were eight-inch, backed up by secondary guns of four-inch caliber and at least a half-dozen Bofors guns for antiaircraft protection.

It is hard to fathom why the Finnish government spent millions of marks on these ships when their deterrent value against the infinitely stronger Baltic Fleet would have been marginal at best, and when the same amount of money could have doubled the number of modern fighter planes in the air force or gone a long way toward correcting some of the field army’s chronic weaknesses. These two curious vessels did brave work during the Continuation War as mobile heavy artillery, pounding Russian targets all along the Karelian Isthmus, but during the Winter War their contribution was minimal: their antiaircraft guns knocked down one or two planes over Turku harbor. Otherwise, they remained icebound for the duration of the conflict.

Most of the naval action took place in the form of classic ship-to-shore gunnery duels. The Finnish coastal artillery was something of an elite force; many of its guns were old, but they were expertly sited, powerful, and manned by keen, disciplined crews.

On December 1, the Soviet cruiser Kirov, escorted by two large destroyers, took on the defenses of Hanko and lost the exchange. The battle was fought under hazy conditions, so details of it are sketchy, but it is certain that one Russian destroyer, closing range recklessly, took at least one large caliber hit, sheered abruptly out of formation, and limped out to sea behind a cloud of smoke. The Kirov had trouble getting the range of the Hanko batteries and did them no significant damage, whereas the Finns were soon straddling it with water spouts. At least one, and possibly two, Finnish shells struck the cruiser on its stern and seriously damaged it. After retiring out of range the Kirov lost engine power and had to be towed back to its base at Tallin, Estonia.

Another duel, about two weeks into the war, took place in the skerries outside of Turku. Two Russian destroyers (possibly the Gnevny and the Grozyaschi) engaged batteries on Uto Island. Again, Russian fire was ineffective (and, again, one must question the competence of any naval commander who orders two destroyers to tackle a battery of ten-inch coast artillery on their own). A single Finnish shell dropped squarely amidships on one of the destroyers; both ships broke off firing after only ten minutes, made smoke, and retired. Ten minutes later the torpedo magazine of the damaged destroyer exploded, breaking the ship in two and causing it to sink in less than two minutes, with heavy loss of life.

The most dramatic of these engagements took place on December 18 and 19, just a week or so before ice brought all naval activity to a halt. The Russian battleship Oktyabrskaya Revolutsia sailed boldly close to the Saarenpää batteries on Koivisto Island, perhaps the most effective Finnish artillery position of the war. The bombardment was preceded by a heavy air attack, which threw up spectacular clouds of dust but did little material damage. Shortly after noon, the Russian battleship hove into range, escorted by five destroyers and a spotting plane. Two Finnish Fokkers were scrambled to nail the spotter plane, but the overzealous and highly accurate Koivisto antiaircraft gunners shot one of them down. Its pilot, Eino Luukkanen, managed to crash-land and walk away uninjured; he later became Finland’s third-ranking ace. By the end of the Continuation War in 1944, he would shoot down a total of fifty-four Russian aircraft.

On this day, the Finnish guns were having trouble; one by one they fell silent after only ten minutes’ fire. The battleship got closer, and its 305 mm. shells began causing casualties and damage. After furious exertions the Finnish gunners managed to get a single ten-inch rifle back in firing order, and their first few shots landed close alongside the Russian ship. The captain decided enough was enough, ordered the helm thrown over sharply, and retired out of range.

The following day, the older battleship Marat, heavily escorted by destroyers and light cruisers, returned to plaster the Saarenpää batteries. The Finnish commander had ordered his men to reply with only one gun at a time so that a slow but steady fire might be kept up even if weapons went out of whack again. The Russians’ gunnery on this occasion was excellent—the Saarenpää site was hit by about 175 rounds, all its buildings were flattened, and the forest cover was stripped away from its battery positions.

With icy deliberation, the Finns replied with one shot at a time, seemingly to no effect. Then, just as the battleship was approaching truly lethal range, a dark column of water heaved up alongside its hull, followed by a cloud of smoke, which made precise observation difficult. Although no fires were observed, the Marat hurriedly retired without further combat, indicating that it had taken a hit near the waterline.

Before ice closed the seas, the Red Navy’s submarines torpedoed two Finnish merchant ships and three neutrals in Finnish waterways—one Swede and two Germans—and sank an armed yacht doing escort duty. Mine fields laid by Finnish vessels, on the other hand, sank two Baltic Fleet subs.