The Russians had been stopped cold against the Mannerheim Line. From POW interrogations, deserters’ reports, and captured documents, it became clear that the Soviets’ morale was poor, that their supplies were not getting through from Leningrad, and that firing squads were working overtime dealing with men, officers and troops alike, who had refused to participate in still more suicidal frontal attacks.

The Finnish generals were swept by a mood of euphoria. General Östermann, who had been so cautious in his handling of the border-zone battles, now came down hard on the side of a bold and ambitious Finnish counter-stroke, a kind of Cannae in the snow, designed to nip off and annihilate the three Russian divisions dug in before Summa. Even the dour and realistic General Öhquist seems to have been swept up by the concept, although it is not always easy to tell, from their postwar writings, which one had the most to do with the plan’s parentage. What is certain is that Östermann forwarded a counterattack proposal to Mannerheim as early as December 11, which Mannerheim promptly rejected as premature.

The optimum date for launching such an operation would have been December 20 or 21, when the Russians were still winded and reeling from their losses. The problem was that several of the Finnish units earmarked for the counteroffensive were still engaged on those days, repelling the last, somewhat enfeebled, attacks or mopping up stubborn Russian pockets still clinging to Finnish positions. The plan was approved by Mannerheim only on December 22, about eighteen hours before H-Hour.

In his memoirs, Öhquist equivocates a bit by saying that he had to go along with the plan or possibly be relieved of his command. Evidence suggests, however, that in the beginning he was just as enthusiastic about it as Östermann. He did, however, insist that the attack plan include strong elements of the only fresh Finnish division on the Isthmus, the Sixth. But the Sixth was designated Commander in Chief’s Reserve, and at the time the counterattack was being drawn up, it was engaged in digging back-up fortifications around Viipuri. Mannerheim procrastinated for about forty-eight hours before agreeing to commit part of the Sixth, and by the time the green light was given, it was too late to launch the attack any earlier than December 23. It was also too close to H-Hour for the Sixth Division to move into its assigned place in any kind of order.

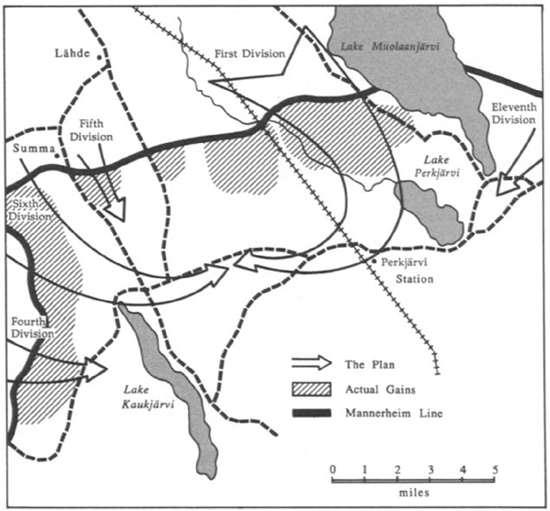

5. Finnish Counteroffensive Objectives and Actual Results

On the map, the plan looked exciting. It was a double-pincers maneuver: a large set of arrows inside a small set of arrows, converging on a big salient in Russian lines that corresponded to the elbow bend at Summa. The Sixth Division would attack the left flank of the salient, the First Division would attack the right. There was a bulge in the Russian salient in front of the Finnish Fifth Division, which would launch a more modest pincers attack of its own. The Fourth and Eleventh divisions would hammer the deeper flanks of the salient, tying down as many Russian troops as they could. The fresh units of the Sixth would be interposed in the line between the battle-scarred Fourth and Fifth.

The Sixth would attack in the area of Karhula, along a southeastern axis, with the objective of cutting the Russians’ main supply artery east of Lake Kaukjärvi. The First Division would strike south and southeast toward the crossroads at Perkjärvi railroad station, then move westward until it linked up with elements of the First.

This was a very bold plan. If it succeeded it might knock three Russian divisions out of the Isthmus fight and certainly ruin the enemy’s timetable for further offensive action. It would, if successful, win perhaps a month of time—time for the voice of world opinion to gather strength, and for military aid from the outside world to reach Finland in sufficient strength to equip two more divisions.

It was, however, utopian; there were so many things wrong with it that one scarcely knows where to begin describing them. The plan itself was vast in scope but diffuse in concentration, and so complex that even an experienced field army would have been challenged to pull it off. The Finnish Army had never in its entire history attempted an offensive operation on this scale. Except for enduring sporadic air raids on Viipuri, the entire Sixth Division was unbloodied. This kind of attack needed armor to give it speed and cutting power and massive, flexible artillery support; it had neither. Artillery support in turn required smooth and reliable communications; Finnish communications were neither. It was a plan that demanded fresh troops who had a clear concept of their roles in the operation, yet the units designated to take part in it had at best thirty-six hours to prepare, and many of them were still involved in violent skirmishing when the orders came down. Add to these factors the normal amount of confusion attendant on a complex offensive, and one has a recipe for military disaster. In the event, the operation was something less than a total debacle, but that was only due to blind luck and the usual Russian incompetence when it came to following up opportunities.

The Finnish generals seem to have forgotten that the Russian soldier is, and always has been, a much tougher proposition in defense than in offense. Dug in and well supplied with ammo, most Russian soldiers would fight to the death, as the invading Germans would soon learn. To attack such an enemy with raw and exhausted troops is risky enough. To do it without any accurate picture of the enemy’s dispositions is sheer folly. And the Finns’ reconnaissance was woefully inadequate. They knew more or less which Russian units were directly in front of them, but they had only the vaguest ideas of what sort of forces they might run into behind that frontline crust.

It is a wonder the attack was launched at all. A blizzard raked the Isthmus just hours before the jumping-off time, dropping temperatures to a brutal twenty degrees below zero. A fierce wind off the gulf lashed the snow into horizontal sheets that cut through snowsuits like a blade. Virtually every unit that had to change position in order to participate in the offensive got lost, delayed, or rerouted. One battery of urgently needed howitzers, attempting to follow a vague set of marching orders in the middle of a snowstorm, finally entrenched itself a mere ten kilometers from where it was supposed to be. The fresh battalions of the Sixth Division, on whom so much depended, were not ordered forward in coherent, easy-to-manage formations, but all at once, in a sprawling mass of men and equipment that straggled over a good part of the Karelian Isthmus. It finally ended up in the right slot, but hours late—its men were suffering from exposure, half its heavy equipment was missing, and its units were appallingly intermingled. Officers were commanding strange men, men were serving in strange units; everybody was cold and tired and rapidly getting exasperated. On viewing this anarchy, several officers on the spot immediately tried to call headquarters and beg that the attack either be postponed until things could be sorted out, or abandoned altogether. The calls never got through. The shooting hadn’t even started yet, but already the fragile Finnish communications net had collapsed under the strain. Telephone communications in most places did not survive much longer than the radio system. Two hours into the battle General Öhquist had lost all contact with two entire divisions.

Ready or not, the attack jumped off at 6:30 A.M., December 23, behind a pathetic artillery barrage lasting ten minutes. The fortunes of the attacking units varied wildly. One battalion of the First Division passed easily as far as the Perojoki River, vigorously attacked a fortified Russian encampment there, killed forty enemy troops and a large number of transport animals, and retired to Finnish lines with only light casualties. The battalion next to it, however, ran into serious resistance from the start, took heavy losses, and had to be rescued by a reserve battalion.

The Sixth Division, to its credit, attacked with surprising élan, broke through a crust of spotty frontline resistance, and penetrated about two kilometers into the Russian rear. There the attackers encountered a large and previously undetected enemy tank park. They were also brought under heavy and accurate shell fire, directed from two large, out-of-range captive balloons. This part of the Sixth’s advance was halted, for good, as early as 10:00 A.M. Two other battalions of the Sixth, part of infantry regiment JR-17 (JR = jalkaväki rykmentti, or “infantry regiment”), pressed onward until early afternoon, then they too encountered stiff resistance. There was no hope of further progress without artillery support. Miraculously, they were able to contact the battery that had been assigned to support them; a barrage was requested on the proper map coordinates. “I’m sorry,” the battery commander replied, “we can’t shoot over there—it’s out of range.” Only then did the Finnish infantry commander learn that the code word he had been issued had been switched, at the last minute, to another artillery battery, one located far out of range. He attempted to use his organic mortars as field artillery, only to discover that the fresh supplies of shells, delivered just before the attack, would not fit the tubes. By late afternoon, every battalion in the Sixth Division was demoralized by that kind of incident, and the soldiers were shaken by their first experience of heavy shelling. Clearly there was not much more the Sixth could do.

The Fourth Division’s attack encountered strong resistance from the start, and its advance gradually angled away from a direction that would have taken it into position to hit the Russian tank park from the rear. New Russian units were now being rushed into the battle zone from nearby sectors, and by midafternoon the Fourth Division, too, was stopped in its tracks.

There was a bitter irony taking shape amid all this confusion. In dealing with the Finnish attacks the Russians were exposing the locations and strength of all their forward reserves of men and armor. The fire control observers accompanying the Finnish infantry were presented with incredibly choice and vulnerable targets—battalion headquarters, truck depots stacked with petrol and ammunition, powder magazines, radio stations, unguarded gun batteries—and were unable to call down a single coordinated Finnish barrage on any of them.

By 3:00 P.M. the Finnish high command had heard enough to know that, instead of a brilliant counterstroke, it now had the makings of a first-class debacle. The order went forth to cancel further offensive operations and withdraw to the Mannerheim Line. The order was ancient history by the time it filtered down to the front. Most local commanders, acting on their own responsibility, had already called off their attacks and were now desperately trying to extricate their men.

By the time the operation was over, the attackers had suffered 1,300 battle casualties and 200 cases of frostbite. It had certainly been the most unimpressive Finnish effort of the war. Considering the scope of the operation, the rotten weather, the inexperience of the men involved, and the hopelessly bad communications, the time that had been allocated for mounting the attack was absurd. The Sixth Division’s troops had been shoved forward in one great ungainly mob; horses’ hooves and sled runners had severed telephone lines, artillery support had been weak and unreliable, and the enemy’s dispositions had been an utter mystery.

In short, the counterattack revealed just how raw, even amateurish, the Finnish Army was at large-scale conventional warfare. The oversights and false optimism, the slipshod planning, the brushed-off details, the euphoric assumptions that characterized both the plan and its execution, were the symptoms of sheer inexperience.

General Öhquist makes a valiant attempt to defend the operation in his postwar writings. He argues that the attack did gain time for the Finns to prepare for the next big Russian push, and he claims that the effort gave “valuable experience” to the officers and men who participated. Perhaps so, but since the Finns never again dared to launch a major counterattack on the Isthmus, it is difficult to see what good all that experience did them. The most discernible result of the operation was gloom in the ranks; the men knew they had made a game try out of a rotten plan, and their opinion of the high command’s competence took a nose dive. The men nicknamed the operation with a Finnish idiom that defies exact translation but that can be roughly and appropriately rendered as “a stupid and misbegotten butting of heads.”

At the time, the Finns had no idea of what sort of losses they had inflicted on the Russians. Postwar evidence, however, does suggest that the enemy suffered at least as many casualties as the attackers and that the confused nature of the fighting, plus the fact that it was taking place up to two kilometers behind Russian lines, really did alarm the Soviet command and throw them off balance. But even if the counterattack did delay the start of the big Isthmus offensive, it was only by a matter of a week or so. The whole curious and abortive business seems to have made very little difference, one way or the other.