RETIREMENT

82. I have nothing set aside for my retirement. Where should I start?

A: 1. Tax-advantaged, retirement-specific buckets. These accounts allow you to contribute money, generally before you pay taxes on it (the Roth IRA is an exception to this rule), and then grow it tax deferred (or tax free in the Roth case) until you withdraw the funds at retirement. Does your employer offer a 401(k) or 403(b) or 457? If so, these are some of the best tools available for retirement saving. In 2009, you can contribute up to $16,500 ($22,000 if you’re older than 50) to these accounts. That might sound like a reach, but it’s likely that your employer is going to help you out with matching dollars. Although some companies have fallen on such tough times that they’ve reduced or eliminated their 401(k) match, many companies will match your contributions to their 401(k) program—sometimes by as much as 50%—which means free money.

If your employer doesn’t offer a 401(k) or similar program, an IRA will be your best bet. An IRA, or individual retirement account, is an account that you establish on your own to save for retirement. The contribution limits are a little lower, at $5,000 (again, $6,000 for those older than 50), but depending on your income and what kind of IRA you choose, they may be tax-deductible. Here are your IRA options:

- Traditional deductible. A Traditional IRA is available for anyone younger than age 70½ who has earned income. Contributions are tax deductible up to the limits, and the money grows tax deferred until you withdraw it at retirement. At that time it will be taxed at your current income tax rate. To be eligible to contribute the maximum to a traditional deductible IRA, your modified adjusted gross income must be less than $55,000 if you’re single or $89,000 if you’re married filing jointly (amounts are for 2009). After that, contribution limits are reduced until you’re no longer eligible at a modified adjusted gross income of $65,000 for single filers and $109,000 for married filing jointly. If you or your spouse aren’t also eligible for an employer-sponsored retirement plan, there are no income limitations.

- Traditional nondeductible IRA. If you earn more than $65,000 as a single filer or $109,000 as a married joint filer and have an employer-sponsored plan, you can still contribute to an IRA; you just can’t deduct your contributions on your income tax returns. The money will grow tax deferred until you withdraw it.

- Roth IRA. There aren’t any age requirements when it comes to a Roth IRA, but there are other restrictions. For you to be eligible to contribute the maximum to a Roth, your modified adjusted gross income can’t exceed $105,000 if you’re single or $166,000 if you’re married filing jointly (again, these are the limitations for 2009). You’re no longer eligible to contribute at all if your modified adjusted gross income hits $120,000 for single filers or $176,000 for married filing jointly. Other differences? Your contributions to the account won’t be tax deductible, but your money grows tax free—when you pull it out in retirement, you won’t have to pay taxes on it. You are not forced, as you are with a traditional IRA, to ever make withdrawals, which means that you can pass this money on to your heirs. And you can make preretirement withdrawals for education and for your first house, as long as the money has been in the account for 5 years, without penalty. You can also pull out your contributions, but not your earnings, at any time, penalty free.

2. Tax-advantaged, nonretirement ways to save. Once you max out your ability to contribute to accounts designated for retirement, you should look at other tax-advantaged ways to save. No, they don’t specifically say they’re for retirement, but in fact all accounts that allow your assets to grow in a tax-deferred way aid retirement. Why? Because they enable you to not have to use those retirement-specific assets for other life needs.

- 529 college savings account. Each state offers at least one version of this savings plan. This plan allows your investments to grow tax free, as a Roth IRA does. Contributions aren’t deductible on your federal return, but your state may offer tax breaks for contributing to their plan. The best part? Distributions used to pay for the account beneficiary’s college education are tax free. If you don’t use the funds for college, however, you’ll pay a 10% penalty and income tax on earnings, but you can change the beneficiary to another qualifying family member at any time.

- Health savings account. If you’re covered by a high-deductible insurance plan, you’re likely eligible for an HSA, which allows you either to deduct your contributions or make them on a pretax basis, depending on your employer. There are no income restrictions, but for you to have an HSA, your deductible must be $1,200 for individual coverage and $2,400 for family coverage. You can then contribute $3,050, if you have self-only coverage, or $6,150 if you have a family plan. Once the money is set aside, you use it for qualified medical expenses—everything from doctor visits to over-the-counter medicines. If the money is used for anything else, you’ll be taxed, and if you’re not older than 65, penalized 10%. Once you turn 65, you can use your account for other expenses without penalty.

3. Non-tax-advantaged ways to save. If you still have money to sock away for retirement, good for you. First, think about whether you have any self-employment income. If so, there are other tax-advantaged options for you. See “I’m self-employed. What’s the best way to save for retirement?” in Chapter 10. If not, it’s time to open a plain-vanilla savings, money market, or brokerage account. You’ll pay taxes every year on the money you earn on your savings or investments in these baskets.

Now that your baskets are established, you need to start funding them. In my book, there is only one way to fund retirement accounts: automatically. If you are putting money into a 401(k) or other employer-based retirement account, that means doing your funding through automatic paycheck withdrawals. If not, however, you need to set this up yourself. Call the bank or brokerage firm that houses your IRA or Roth or 529 and ask to have a certain amount of money transferred automatically to the retirement account every month. You have to make this call only once, and it will continue to happen until you stop it (which you shouldn’t). The miracle is how fast your savings manage to add up.

THE MATH

Want to make sure you max out your Roth or Traditional IRA? Start early and automatically contribute $416.66 a month if you’re younger than 50, or $500 a month if you’re older. By the end of the year, you’ll have hit your target.

I Also Need to Know…

Q: Which is a better option for saving for retirement, a 401(k) or a Roth IRA?

A: Assuming you’re eligible for both—in other words, you have a 401(k) through your job and you are within the income requirements for a Roth (less than $120,000 if single and $176,000 if married filing jointly)—you should look first at that 401(k). If it has an employer match, contribute enough to that account first to grab all the matching dollars. After that, the advantage to the 401(k) is its higher contribution limits ($16,500 versus $5,000), which means you’ll be able to save more if your income allows for that. The advantage to the Roth is flexibility (you can get at the money if you need it) and investment choice (you’re not limited to the choices on your employer’s menu).

But here’s an important point: You don’t have to choose, because you can, and should, have both. A Roth IRA has more than a few advantages that you don’t want to pass up, particularly the fact that your money grows tax free and you can withdraw your contributions at any time without penalty for something such as a down payment on a house or education expenses.

My advice to you is to tag-team your retirement. Contribute enough to your 401(k) to grab your match, if your employer offers one, and then shift your focus to your Roth. If you hit the limit on the Roth and have money left over, go back to the 401(k) until you reach the limit there.

Q: What is a Roth 401(k)?

A: Essentially, it’s the best of both worlds. A Roth 401(k) is set up through your employer, although because it is a relatively new concept (it was introduced by the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001), only about 12% of employers offered it in 2007. Like a traditional 401(k), it has a $15,500 cap on contributions ($20,500 for those older than 50) and no income restrictions.

But like the Roth IRA, contributions are made with after-tax dollars, meaning that your savings grow tax free.

How do you know whether to go with a Roth or traditional 401(k) if your employer offers both? It’s a matter of hedging your bets. If your income, and thus your tax responsibility, is low now, you’re probably better off going with the Roth, because you’ll lock in that low tax rate. If you make a good bit now and expect to have a lower tax rate in retirement, put off your tax responsibility by going with a traditional 401(k). If you can’t decide, you do have the option of contributing to both, although your contribution limit is still $15,500 combined.

Q: I heard that the Roth 401(k) is going to expire soon. What happens to my money if it does?

A: The law authorizing the Roth 401(k) was set to expire in 2010, but it’s since been made permanent, so there’s no need to worry.

Q: What is my modified adjusted gross income, anyway?

A: This term comes into play only when you’re talking about IRAs. It is used not only to figure out eligibility for Roth IRAs but also to determine what portion, if any, of your contributions to a traditional IRA will be tax deductible. You can figure out yours by taking your adjusted gross income—found on your most recent tax return—and adding back certain items, including student loan deductions, IRA contribution deductions, deductions for higher-education costs, and foreign income. The higher your modified adjusted gross income is, the less you’ll be able to deduct when it comes to your Traditional IRA contributions. You may also eliminate your ability to open a Roth IRA if you reach the income limitations ($120,000 for single filers, $176,000 for marrieds filing jointly).

Q: I’m only 25. Why do I need to think about retirement already?

A: The earlier you start investing, the more you’ll have amassed when it’s time to retire. Obvious, right? But what might not be so obvious is that the earlier you start investing, the less you have to contribute overall. That’s right, you’re actually saving money by saving money. Let me show you what I mean:

Let’s take two people, both your age. We’ll call them Jane and Bob. Jane starts investing $100 a month at age 25 and continues investing that same amount until she retires at 65. Bob, however, puts off saving for retirement until he’s 40, at which point, he starts investing $350 a month for the next 25 years:

TOTAL CONTRIBUTED BY AGE…: 25

JANE: $1,200

BOB: $0

TOTAL CONTRIBUTED BY AGE…: 30

JANE: $6,000

BOB: $0

TOTAL CONTRIBUTED BY AGE…: 35

JANE: $12,000

BOB: $0

TOTAL CONTRIBUTED BY AGE…: 40

JANE: $18,000

BOB: $4,200

TOTAL CONTRIBUTED BY AGE…: 45

JANE: $24,000

BOB: $21,000

TOTAL CONTRIBUTED BY AGE…: 50

JANE: $30,000

BOB: $42,000

TOTAL CONTRIBUTED BY AGE…: 55

JANE: $36,000

BOB: $63,000

TOTAL CONTRIBUTED BY AGE…: 60

JANE: $42,000

BOB: $84,000

TOTAL CONTRIBUTED BY AGE…: 65

JANE: $48,000

BOB: $105,000

TOTAL CONTRIBUTED BY AGE…: Total contribution

JANE: $48,000

BOB: $105,000

TOTAL CONTRIBUTED BY AGE…: Total value of retirement account

JANE: $351,428

BOB: $335,079

Total earnings are based on an 8% return on investment.

You’re not seeing things. Bob contributes twice as much as Jane but ends up with less money for retirement. That’s the power of compound interest: Jane’s investments are boosted by the time they have to grow.

Q: Which kind of IRA is better for me?

A: Generally speaking, if you’re eligible for the Roth, that’s going to be your best bet, particularly if you’re younger than 50. You’ll lose the tax deduction, sure, but the advantages are greater overall. Going forward, we don’t know what tax rates will be, but we know what they are now, and it’s a safe bet that they won’t go any lower. That means that it makes sense to get your money in a tax-free account if you can. And note: If you haven’t been able to contribute to a Roth because you earn too much money, 2010 presents a great opportunity. You can convert a Traditional IRA to a Roth regardless of income. You’ll have to pay income taxes on the conversion; as long as you don’t have to raid your IRA to do so, this is a good idea.

83. I am a married, stay-at-home parent. How do I save for retirement?

A: As a nonworking spouse, you can save money in what’s called a spousal IRA as long as you and your spouse file a joint tax return and his or her income is at least as much as your contribution. There are limits to how much you can contribute each year to an IRA, and currently they are set at $5,000 if you’re younger than 50 and $6,000 if you’re 50 or older.

Your spousal IRA can be in the form of either a traditional IRA (where your contribution is tax deductible in the year you make it, and you pay the taxes as you withdraw the money once you’re retired) or a Roth IRA (where you pay taxes on the money as you earn it, but the money can then grow tax free forever). If you qualify for the Roth, that would be my pick. Not only is the tax treatment advantageous but also the Roth is flexible. You can pull out your contributions at any time for any reason, and you can withdraw income on those contributions for education or to buy your first home after five years. However, the adjusted gross income on your joint return must be less than $166,000 for you to contribute the maximum to a Roth.

A traditional IRA doesn’t have income limits. But if your spouse is also covered by a qualified retirement plan at work, the tax deduction on the contribution starts to phase out at a modified adjusted gross income of $166,000 (in 2009). You are no longer eligible for the tax deduction if your modified adjusted gross income is $176,000 or more.

THE MATH

A contribution of $5,000 a year may not seem like much, especially when compared with the amount your partner contributes to his or her 401(k) each year, but it adds up over time:

- In 10 years you’ll have $74,721.

- In 15 years you’ll have $143,225.

- In 20 years you’ll have $243,796.

- In 25 years you’ll have $393,630.

- In 30 years you’ll have $616,861.

I Also Need to Know…

Q: Why do I need my own retirement plan if my spouse is saving enough to cover us both in retirement?

A: Just like having your own bank account in a marriage, having your own retirement savings account gives you a bit of independence. You have control over your own retirement, and not only does that feel good but it also protects you against the unexpected. Trust me—once you start to see the balance tick up because of your contributions, you won’t want to stop saving. It’s also in your best interest when it comes to taxes, because in most cases you’ll be able to save up to twice as much money in a tax-advantaged way.

Q: Will I get Social Security benefits that are based on my husband’s income? How are those calculated?

A: Probably. A spouse who hasn’t worked at a paying job or who has accumulated low earnings throughout his or her career is typically entitled to up to half of the working spouse’s benefit amount. You’ll start to receive your benefit when your husband starts taking his or at age 62, whichever comes last.

One thing to note, though, is that if you’re eligible for your own benefits—say you decide to go back to work once the kids are settled in school—the SSA will pay you your own benefits first. If that amount happens to be lower than what you’d receive from your husband, the SSA will combine the two benefits to equal the higher amount, but you won’t get the total of both.

If you’re at full retirement age and you’re eligible for both your own benefit and your husband’s, you can choose to receive his now so that your benefit continues to grow. (Social Security benefits increase by as much as 8% for each year you delay taking them between ages 62 and 70. For more on how this works, see Chapter 10). You can file for your own benefits in a few years and your monthly check will be higher because it will be based on the delayed benefit.

An Example

Shannon is 62 years old. On the basis of her earnings, her Social Security monthly benefit is $998. Her husband, Jack, who is 68, just began taking his benefit in the amount of $2,842 a month. That means that because her benefit from Jack’s Social Security is higher, the SSA will pay Shannon all of her own monthly benefit, plus $423 of her spousal benefits from Jack, for a total of $1,416—50% of Jack’s monthly benefit.

Shannon could maximize her benefits by delaying taking her own Social Security benefits and just taking her $1,416 in spousal benefits as Jack’s wife for a few years. That way, when she reaches age 70, her own monthly benefit will be $2,494 (adjusted for inflation). What’s the difference?

- If Shannon takes $1,416 starting at age 62, which is based on a combination of her husband’s benefits and her own, and she lives 30 more years, she’ll receive a total of $509,760.

- If Shannon takes $1,416 starting at age 62 from her husband’s benefits, delays taking her own until she’s 68, and lives 30 more years, she’ll receive a total of $820,224.

The difference? A whopping $310,464.

Q: What if my husband and I get divorced? Do I lose my stake in his Social Security benefits?

A: No, provided you were married for more than 10 years. However, if you remarry, you generally cannot collect benefits that are based on your former spouse’s benefits.

84. I’m self-employed. What’s the best way to save for retirement?

A: There is one big downside to being self-employed when it comes to saving for retirement: You lose the employer match that many employees get when they contribute to a company-sponsored 401(k).

Fortunately, there are a lot of upsides, starting with the fact that you can contribute more each year than a person who works for someone else.

If you’re eligible for a Roth IRA (to make the maximum contribution, your modified adjusted gross income must be less than $105,000 for single or married filing separately or $166,000 for married filing jointly), start there. But that accounts for only the contribution limit of $5,000 a year ($6,000 if you’re 50 or older).

For the rest of your retirement savings contributions, look to the solo 401(k). This option allows you to contribute up to $16,500 in 2009 as an employee (i.e., your own employee). That’s the same contribution limit as a 401(k). Then, as the business owner, you can also contribute 20% of your self-employment income, up to a combined maximum of $49,000 (in 2009, these limits adjust each year for inflation). And if you’re older than 50, you can make catch-up contributions of an extra $5,500 each year. All in all, if you had a good year, you could contribute $70,000.

Better still, contributions to a solo 401(k) are tax deferred. You’ll be taxed when you withdraw the money after age 59½ as with a traditional 401(k), you’ll incur a 10% penalty if you withdraw the money earlier.

A solo 401(k) can be a great option for sole proprietors, but if you have any employees (other than your spouse), you’re not eligible. In that case, you should consider something called an SEP (simplified employee pension) IRA. This account allows you to contribute 20% of your business income, up to $49,000 in 2009, but doesn’t allow you to also make an employee contribution for yourself. Your contributions will be tax deductible, and you can open plans for your employees and contribute on their behalf. You’ll incur the same penalties as you would with a 401(k) if you make an early withdrawal.

Other options include Keogh plans, which tend to make sense only for high-income business owners with low-income employees (for instance, a doctor might open a Keogh because while his income is likely good, he may pay his receptionist very little). A SIMPLE (savings incentive match plan for employees) IRA is the opposite of what its name implies—it is quite complicated—and is a better option than a SEP only if you have a good number of employees. That’s because with a SEP IRA, you’re contributing your own money to your employees’ accounts. With a SIMPLE IRA, the contribution is a salary deferral, which means they are contributing their own money. To be eligible for a SIMPLE IRA, you must have fewer than 100 employees.

One thing to keep in mind with all of these: You want to think about the big picture. Maybe you don’t have any employees now, but do you envision a time when you might? If so, you should probably think ahead and go with a SEP IRA instead of the solo 401(k).

THE MATH

What’s the tax benefit here? Let’s take a look. The chart below compares Shawn and Mary. Shawn makes the maximum contribution to his solo 401(k) each year, while Mary doesn’t. They both have business incomes of $100,000.

Net income

Shawn: $100,000

Mary: $100,000

Deductions

Shawn: $33,650

Mary: $33,650

Solo 401(k) contributions

Shawn: $35,087

Mary: $0

Taxable income

Shawn: $21,263

Mary: $66,350

Tax due

Shawn: $3,854

Mary: $9,118

Self-employment tax due

Shawn: $15,300

Mary: $15,300

Total tax

Shawn: $19,154

Mary: $24,418

Tax savings

Shawn: $5,263

Mary: $0

Source: T. Rowe Price.

I Also Need to Know…

Q: Can my spouse contribute to my solo 401(k) if she works for the business?

A: Yes, if she is paid by the business. And if she can afford it, she should contribute for herself too, because it doubles the amount that you can put away for retirement. A good deal, any way you look at it.

Q: I work full time and I have a 401(k) through my employer. Can I also have a SEP IRA or a solo 401(k) for my self-employment income?

A: Yes. If you choose a solo 401(k), though, your contribution limits may be reduced. If you want to contribute to a solo 401(k) and an employer-sponsored 401(k), your contributions to both as an employee have to fall under that year’s limitations. However, you can still contribute the additional 20% of your self-employment income. So if you contributed, say, $10,000 to your employer’s 401(k), you could still contribute $6,500 to your solo 401(k), plus 20% of your business income.

Q: If I decide to leave my full-time job to start my own business, what should I do with my 401(k)?

A: You can leave it in place, if you want, but your best bet is to roll that money over into either a SEP IRA or a solo 401(k), whichever tool you’ve chosen to continue your retirement savings. For more information about rolling over these assets, turn to “How do I roll over a 401(k)?” in Chapter 10.

85. What is an annuity?

A: An annuity is an insurance product sold as an investment. You deposit a certain amount of money with an insurance company, then receive it back at a later date, sometimes in a lump form, other times in the form of “paychecks” at regular intervals. There are several basic types of annuities—and many varieties, one of the reasons that the world of annuities can be tough to decipher. But one thing is clear: You should understand what an annuity is before you tackle the next question, which is “Should I buy one?”

- Variable annuity. A variable annuity takes the money you deposit and invests it, generally in mutual funds. The performance of those investments ultimately determines your payouts. If the stock market rises, your payout likely will too, and vice versa. There is sometimes a minimum return, or a guarantee, that is set at the time of purchase. You may pay extra for this feature, however. Fees on variable annuities are often high (higher than they are on mutual funds outside of annuities). Be sure that you understand the costs of making this investment.

- Fixed annuity. A fixed annuity takes the money you deposit and invests it, guaranteeing a return. Your payout will be the same each month and is based on how much you contribute, your age, and the interest rate when you purchased it. These annuities are for individuals who have a lower tolerance for risk than those investing in variable annuities. Fees are generally built into the interest rate, much as they would be with a standard savings account. The bank earns 6% on your money, for example, but gives you an interest rate of 5%. The fee schedule is generally not as complicated or cumbersome as with a variable annuity, but you still need to understand how much making this investment will cost you.

- Deferred annuity. A deferred annuity is one type of fixed annuity or variable annuity. It allows you to put off payments for a period of time, essentially until you need them, which is why it is often sold for long-term retirement planning. The money invested in your account grows tax deferred and when you’re ready (and contractually able), you will start receiving payments. This kind of annuity typically comes with a death benefit—if you die, the beneficiary of the account is guaranteed the principal and investment earnings.

- Immediate annuity. An immediate annuity gives you your paycheck right away in return for your investment of a lump sum—hence the name immediate. You can pick the length of time—five years, your lifetime, even your spouse’s lifetime—that you’ll receive your payments. The longer the time frame, the lower your payments. You pay taxes only on the part of your annuity payment considered earnings, not the principal. These can also be fixed or variable.

Keep in mind that while the stream of income you receive from any annuity may be steady as advertised, it could be eroded by inflation, because while you’ll get the same amount of money, it won’t go as far. Most annuities will give you the option to have your payouts increased each year to account for that. You will pay more for that guarantee.

Q: Are annuities safe?

A: Before 2007, nearly everyone you asked that question would have answered yes. Now, after the fall of insurance giant AIG, we’re not so sure. But insurance companies are regulated tightly, and most states cover insurance companies if they fail. Coverage amounts vary by state, but ranges from $100,000 to $500,000. If the value of your annuity is less than that, or if you have two annuities with two different insurance companies valued at less than that, you’re covered much like the FDIC covers money in your bank account.

And if the value is not? Much depends on the financial health of your annuity provider. Check out the ratings on Web sites such as A.M. Best (www.ambest.com/) and Moody’s (www.moodys.com), but keep in mind that these are just ratings and not guarantees. (They, too, let us down in recent years.) Understand where the rating falls on the charts as well. An “A–” may sound good, but at A.M. Best, it’s only the fourth highest rating behind AAA, AA, and A.

Q: How do I buy an annuity?

A: Annuities are sold by insurance agents but also through some financial planners, banks, and life insurance companies. Whoever you work with, make sure that he or she is licensed by your state’s insurance department. And if you feel pressured to buy or do not fully understand what you are buying, walk away.

Watch Out for These!

- Fees. The fees charged on annuities tend to be high—more than what you’d pay for your standard investment account. Actual costs vary, but expect to pay an annual fee upward of 2% of the assets you deposit, as well as surrender fees if you want to withdraw your money early. These tend to go down every year—they generally start at 7% in the first year and go down 1% each year thereafter until you’ve left the money in place for seven years.

- The fine print. Annuities are complicated—so complicated that even many of the people who sell them do not understand them well enough to explain them to you. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t buy one—only that you shouldn’t buy one if you don’t understand it. And if the person pitching you doesn’t have the ability to explain it to you, you should find another source.

- The suggestion to put an annuity into an IRA. Annuity funds grow tax deferred; therefore, you don’t need the double protection of an IRA.

86. When should I cash out my 401(k)?

A: Let’s be clear: You shouldn’t. You don’t want to “cash out” your 401(k) (or your IRA or any other retirement account) all at once. Instead you should consider taking distributions from your 401(k) without penalty when you reach age 59½. (Understand, though, that you don’t have to begin taking distributions until you reach age 70½.)

How do you make the decision on when to begin distributions? The first and most important question: Do you need the cash? If you need the money to live on, or if you’ve stopped working and aren’t yet receiving Social Security benefits, or if you are receiving Social Security benefits but they’re not enough to meet your needs, then it’s the right time to start.

But remember, this is simple math: You have a certain amount of money, and you need it to last an estimated number of years. The sooner you start pulling it out and spending it, the less money you’ll have down the road. For more information, turn to “How do I make my retirement funds last as long as I do?” in Chapter 10.

Next, look at how your investments are doing. If they’re way down, you will want to put off pulling money out of that account if possible. That will give your money more time to grow—and come back—tax deferred.

Bottom line: If you’re worried that your money isn’t going to make it to the end of your life and if you can continue to work or you have adequate personal savings to support yourself for a while, go ahead and spend that down before you tap into your 401(k) or your IRA.

Once you’ve decided that it’s time to start taking distributions—or you turn 70½—you want to pull your money out in a way that minimizes your tax liability. Distributions from 401(k) and IRA accounts are income, and they are taxed as such.

That means that you must consider your tax bracket. If you’re on the cusp of moving to a higher bracket and if taking a certain amount in distributions will push you there, then it’s worth cutting your distribution back a bit—and possibly your spending as well—to stay in the less-expensive bracket. In general, retirees tend to have less in earned income as they get older, which means that as time passes, you might have a bit more leeway to pull out more.

One other factor to consider: Social Security benefits. In general, these aren’t taxable, unless you have enough additional income to push them over the threshold. Your income from 401(k) and IRA investments could do that. Here’s how to do the math:

- Add half of the total benefits you received to all of your other income, including any tax-exempt interest and other exclusions from income.

- Then compare that total amount with the base amount for your filing status:

- If married filing jointly: $32,000

- If single, head of household, qualifying widow/widower with a dependent child, or married, filing separately, and you did not live with your spouse at any time during the year: $25,000

- If married filing separately and you did live with your spouse at any time during the year: $0

If the total is more than your base amount, some of your benefits may be taxable.

An Example

Josh is single and 65, and his monthly Social Security benefit is $1,150, or $13,800 a year, about the average. He can also pull $18,100 out of his retirement accounts each year—as long as he has no other income—without his benefits being taxed.

THE MATH

Jackie is 60 years old, and every year, she and her employer contribute $10,000 to her 401(k). She now has $600,000 in her account. She can retire now and begin taking distributions, or she can continue to work for a few more years. She needs at least $2,000 a month to get by.

If she opts to retire now and pull that amount out each month, her money has only a 75% chance of lasting until she is age 95. If she wants a 90% chance—and she should—she must reduce her living expenses so that she can pull out only $1,750. Or she can continue to work for a bit longer. In fact, if she waits just five years and continues to stash away that $10,000 a year, she’ll be able to pull out $2,588 a month without worrying.

Source: T. Rowe Price Retirement Income Calculator.

I Also Need to Know…

Q: I’ve heard that I should pull my money out of my retirement accounts sooner rather than later because taxes are low…and likely to go up. Thoughts?

A: There are varied opinions on this question: Some people say that because taxes are relatively low right now (as I wrote this, the tax cuts from the administration of George W. Bush were still in place), and there’s a good chance they’ll only go up from here. That would mean that paying taxes on money now rather than later is a good gamble. Other people think that delaying your withdrawals to allow for additional tax-deferred growth is the key, no matter what. Me? I can understand both sides of the argument. But in the end, I’m in the second camp. Delaying taxes has almost always been the better bet, except if you are in a very low tax (10% to 15%) bracket to begin with. If that’s the case, it likely won’t make much difference either way.

Q: What are the other rules in regard to distributions?

A: You might have heard that required minimum distributions were suspended in 2009, which means you’re not required to pull money out of your retirement accounts during that year.

Under normal circumstances, the IRS requires that you withdraw a certain amount from your tax-deferred retirement accounts each year, beginning when you turn 70½, or the year that you retire—whichever is later. If you have an IRA or you own more than 5% of the business sponsoring your plan, you must begin withdrawing at age 70½, regardless of whether you’re still working.

These rules apply to 401(k), 403(b), and 457(b) accounts; traditional IRAs, SEP IRAs; and SIMPLE IRAs. They do not apply to Roth IRAs as long as the owner of the account is still alive.

Next, you have to do a little math. You have to calculate the amount you’re required to withdraw. This is based on the account balance at the end of the prior year and your life expectancy factor, as determined by the IRS (you can find yours at www.irs.gov). Essentially, you’re dividing your account balance by your life expectancy factor. One thing to note: There are three tables of life expectancy factors used by the IRS. The first is for account beneficiaries, the second is for account owners who have a spouse more than 10 years younger than they are, and the third is for singles and account owners with a spouse less than 10 years younger than they are.

An Example

Let’s take Richard. Say that on December 31 of the year before he turns 70½, he has $500,000 remaining in his 401(k). His wife, Sally, is 65. According to the IRS, Richard’s life expectancy factor is 27.4. That means that his minimum distribution for this year is $18,248.18.

Q: I have a lot saved for retirement, but I don’t need the money right now. Is there any harm in waiting to take distributions?

A: Not really. You have two risks. The first is that by leaving the money invested, you could potentially lose principal. But you can solve that problem by making sure you move any money you could potentially need in the next five years into safe havens within your retirement accounts (an exercise you should repeat annually, by the way). The other risk is that you’ll delay living. It’s a tricky balance between making your money last until the end and not pinching pennies throughout retirement only to wind up with millions on your deathbed. You want to enjoy life, and if you have the money to do that without tapping your retirement fund, then so be it. But if you’re passing up vacations or other enjoyable experiences because you have the money but don’t want to spend it, you may regret that later on. Consider your priorities carefully.

87. How do I roll over a 401(k)?

A: First, good for you for asking. Too many people—almost 50%!—choose to cash out their 401(k) when they leave a job, then blow the money and set themselves back years when it comes to saving for retirement. I did it myself, in fact, after I left my first job back in my early twenties. It’s a huge mistake, because not only are you spending money that should be earmarked for retirement but also you’re losing a lot of it (20% to 30%, depending on your income) in taxes. Add that to the 10% penalty you’ll pay for pulling out of the plan early if you’re younger than 59½, and you’ve lost nearly half your money to the government. Ouch!

When you leave a job you have these better options:

- Leave your money in your former employer’s plan. Some companies will allow you to leave your money in its 401(k) plan even though you no longer work there. You typically must have $1,000 to $5,000, minimum, in the plan for this to be an option. If you like your investment options, and the fee structure is palatable, this is a fine choice.

- Move the money to your new employer’s plan. Again, this option hinges on the investment options offered. If you like them, this move can make your life easier administratively, particularly if you’ll be contributing new money to this new employer’s plan.

- Roll the 401(k) into an IRA. This will give you more investment options, because IRAs tend to offer more flexibility than company-sponsored plans. Also, administratively, rollovers simplify life. Think about it this way: Over the course of your career, you’re likely to have 12 different jobs. If you had 12 different 401(k)s with 12 different employers, your head would spin from all the paperwork (or if you’ve automated, all the e-mails). And keeping your asset allocation in line across all those accounts would be next to impossible. Rolling all the 401(k)s into a single IRA, however, streamlines your investments.

Rolling over is a simple process. It starts with sitting down with human resources or the plan administrator at your former job. They’ll have you fill out some paperwork, and then you can have them cut a check in the amount of your account balance and send it to an IRA account you’ve opened with a brokerage firm or bank. To select the home for the IRA, look at the administrative fees for the account. They can be as much as $50 a year, but most banks will waive them if you reach a certain account balance, so it pays to shop around. And, if you plan on actively trading stocks in your account, look at trading costs as well. They average about 4% or 5% of the amount you trade at full-service brokerage firms and $7 to $20 at discounters.

An important note: When you pull the trigger on the rollover, you want to make sure that the company doesn’t cut the check to you personally. If they do, it will be treated for tax purposes as income, as if you cashed out. If you take possession of the check, you’ll also have only 60 days to deposit it into an IRA—if you miss the deadline, you’ll be hit with a 10% early withdrawal penalty.

THE STATS

- 45%: The percentage of 401(k) participants who cash out when they leave a job

- 32%: The percentage who leave the money in their current 401(k)

- 23%: The percentage who roll the funds over into an IRA or other retirement plan

THE MATH

How much damage can you do by cashing out your 401(k)? Lots!

Take a 35-year-old in the 28% tax bracket who expects to retire at age 65.

- His 401(k) balance is $50,000.

- If he cashes out, he’ll net $31,000.

- If he rolls the money into an IRA and invests it at 8%, at retirement he will have $546,786

The difference: $515,786

Q: As part of my compensation package, I have employer stock. Can I roll that over as well?

A: You can, but you probably don’t want to. This is, in fact, the major caveat when it comes to rolling over your 401(k): Company stock gets special tax treatment under the employer-sponsored plan. Luckily, you can roll a portion of your 401(k) over and leave the company stock behind. Here’s how it works:

Say you were given $10,000 worth of company stock, and it’s now worth twice as much. If you roll that $20,000 worth of stock into an IRA, when you withdraw the money down the road, it’ll be taxed as ordinary income and you can lose up to 35%. But leave it in the 401(k) and only the original investment—$10,000—will be taxed as ordinary income when you take distributions. The rest won’t be taxed until the stock is sold, and then only at a long-term capital gains tax of 15%.

That can mean big savings. In this example, the employee would eventually pay $7,000 by rolling the company stock into an IRA. If the employee keeps it in the 401(k) plan, the tax will only pay $5,000 in taxes, a savings of $2,000. This math assumes that the employee is taxed at the highest rate of 35%. The more the stock grows, the more the employee saves.

Q: I’m changing jobs. I want to roll over my 401(k), but I was told that I can’t keep my employer’s contributions. Why not?

A: Many employers require you to remain with the company for a specific length of time to be eligible to take matching dollars with you when you leave (this is called vesting). If you don’t meet that threshold, you can roll over the money you’ve contributed out of your own paycheck, but you’re going to leave behind any contributions made by your employer.

Nearly half (44%, according to a 2007 study by Hewitt Associates) of companies offer immediate vesting to their employees, but that means that more than half don’t. Commonly, companies will offer graded vesting over five years, which means if you leave after one year, you’ll get to keep 20% of their contributions; after two, you’ll keep 40%; and so on. At other companies, you’re vested after three years—leave before, and you’ll get nothing from their end, but stick it out and you can keep it all. If you can, it often pays to hang around, but you have to weigh a variety of variables, including your own happiness, your career, and your salary. In some cases, a bump in compensation is enough to make up the difference.

88. My employer is going to stop or reduce matching my 401(k) contributions. What do I do?

A: Unfortunately, many companies can no longer afford their matching programs in the current economy. Some are cutting back on contributions, others are eliminating them altogether.

That doesn’t mean you should stop contributing. As you know, your 401(k)—with its annual cap on contributions of $16,500 for 2009—allows you to kick in about three times the money you can put into any sort of IRA. That makes it a valuable asset as you prepare for retirement. Instead, look into the following.

- Your investment choices. Some 401(k)s offer a wide menu of terrific, low-cost investment options. Others pale by comparison. Meager choices matter less when your employer is offering you an instantaneous return on your investment in the form of a company match. When that match goes away, however, choices matter more. If you have never liked your choices, take the first $5,000 off the table ($6,000 if you’re older than 50) and contribute that money to an IRA or Roth IRA instead. See “I have nothing set aside for my retirement. Where should I start?” in Chapter 10 to figure out which is right for you. Put any the difference between that $5,000 (or $6,000) and the rest of your retirement-designated funds into your 401(k) and pick the best of the options on your limited menu.

- Contributing more. Chances are you’ve run some scenarios on your retirement. You’ve figured out how much money you need to make your retirement work—and you’ve figured matching dollars into those equations. (If you haven’t run your retirement numbers, you can get started in Chapter 10 with “How much do I need to set aside for retirement?”) If your employer is no longer contributing, making that retirement date will require increased savings.

I Also Need to Know…

Q: Any ideas for finding the money to increase my contribution?

A: Sure. Unless you can take on a part-time job or work overtime, you’re going to have to find the money in your own wallet, so to speak. Comb over your expenses and see where you can cut back. When you come to something that’s discretionary—for example, you enjoy having cable television but you can live without it—think about whether you can eliminate that expense or, failing that, cut back on it. If you really want the cable, maybe you keep it but cancel HBO. The goal is to cut as much fat as possible by making conscious choices that allow you to keep the things that matter most in your life while eliminating those that are not so meaningful but often expensive.

THE MATH

If you make $45,000 a year and save 10% of your salary in your 401(k), that’s $4,500 a year. Let’s say your employer usually matches half, but after some financial trouble, no dice. Want to make up that $2,225 on your own? Here’s how to get it done:

- Bring your lunch to work just twice a week

- Found money: $13/week

- In the pot: $676/year

- Clip coupons for the grocery store

- Found money: $10/week

- In the pot: $520/year

- Cancel your landline phone service—you have a cell, right?

- Found money: $45/month

- In the pot: $540/year

- Dine out one less time each month

- Found money: $50 or more a month

- In the pot: $600/year

Total: $2,336

Q: Do I pay taxes on the money my employer contributes to my 401(k)?

A: With a 401(k), all contributions grow tax deferred, whether they come from you or from your employer. You’ll pay taxes when you withdraw the money in retirement.

89. I have accepted early retirement benefits from my employer. These benefits include a lump-sum retirement distribution. What should I do with the money?

A: Nothing, until you read this answer. Even then, I want you to move slowly. You don’t want to make a rash decision, as this money likely represents a big chunk of your retirement. And once it’s gone, you can’t get it back.

Lump-sum retirement payouts are a more frequent occurrence these days, largely because of the economy. It’s overwhelming, handling a check that big, particularly when all or part of your standard of living in retirement is riding on it. To start, I’d put the money in an FDIC-insured savings or money market account. If you’re looking at more than $250,000 (the current limit on FDIC insurance), put it in two or three or more accounts at different banks so that you don’t run afoul of those limits. FDIC insurance is important because it protects your money in case of a bank failure.

Then it’s time to plan. You need to answer some important questions:

- What does this money represent in terms of your retirement nest egg? Is this it? Will you continue to work and add to it?

- How much will you need each year to live in retirement? How much of that money will come from this nest egg and how much from other sources such as Social Security?

- How much do you need this money to grow to satisfy your retirement needs?

These are complicated questions with complicated answers, which is why I want you to talk to a financial advisor. If you don’t already have a financial advisor, hire one, even if it’s just on a temporary basis. For advice on how to do that, see “I’d like to hire a financial advisor, but after all the frauds in the news recently, I’m nervous. Can you help?” in Chapter 2. An advisor will be able to look at your whole financial picture, including your assets, such as retirement funds and other savings accounts, and your liabilities, such as a mortgage, and determine how the money can best be put to use.

One option an advisor might suggest is an immediate annuity, which provides an infinite stream of income. For people used to receiving a paycheck, I recommend using part, not all, of that lump-sum payout to buy yourself a stream of income that’s guaranteed to last for the rest of your life. An immediate annuity works best when you use the annuity payouts in combination with Social Security benefits to cover fixed expenses—housing, food, utilities, transportation—then invest the remainder of the lump sum so it can continue to grow. For more on this subject, see “What is an annuity?” in Chapter 10.

Bottom line: Give yourself plenty of time to process your decisions, think about the best way to put it to use, and talk over your options with an expert. Whatever you decide to do, have a detailed plan in place before you act.

90. How much do I need to set aside for retirement?

A: If only there were an easy answer to that question, more people would be able to reach their retirement savings goals. For many, pinpointing a number seems so complicated, and they’d rather sit back and do nothing or pull a goal out of thin air.

But that’s a huge mistake. If you don’t calculate how much you’ll likely need in retirement, chances are you’re not going to get anywhere close. A recent study by Hewitt Associates projected that fewer than one in five—one in five!—workers are saving enough to meet their retirement needs.

We’re living longer than past generations did, so we need more money at our fingertips than ever before. Financial advisors used to have people strive to replace 75% to 80% of their income in retirement. Now that’s not nearly enough, especially if you want to travel extensively or don’t have adequate medical coverage. The Hewitt study suggests that men need to replace 123% of their final salaries and women need to reach 130%. That’s per year—so if your final salary is $100,000, you should strive to replace $123,000 a year if you’re a man or $130,000 a year if you’re a woman.

You may find those numbers out of reach, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try to get close. Shoot for replacing 100% of your income, and if you end up with more, great.

To ballpark how much you need to save, figure out how much you’ll get from the SSA. You can do that by estimating your benefit with the calculator at www.ssa.gov (choose the option that allows you to see your monthly benefit in inflated dollars). You’ll notice that the longer you put off taking your benefits, the more you get per month. For more on why that is, and how you can work it to your advantage, turn to “When should I begin to collect my Social Security benefits?” in Chapter 10.

Once you have an estimate of your Social Security benefits, fill out the Ballpark E$timate worksheet below, from the American Savings Education Council.* If you’re married, each partner should fill out a separate version. Be sure to understand that this figure is just an estimate, and if you fall way short, you can always work a little longer, invest more aggressively, or put off collecting Social Security benefits for a few years.

BALLPARK E$TIMATE WORKSHEET

- 1. How much annual income will you want in retirement?

- (Tip: You’ll need at least 70% of your current gross income to maintain your standard of living. If you want to travel or you need to cover your medical insurance, aim for 90%. If you need to cover all of your health-care costs, want a lifestyle that is more than comfortable, and need to save for long-term care, aim for 100% to 130%.)

- 2. Subtract the income you expect to receive annually from:

- Social Security benefits $________

- (Tip: If you make less than $25,000, enter $8,000; $25,000 to 40,000, enter $12,000; and more than $40,000, enter $14,500. Note for married couples: The lower earner should enter the higher of either the lower-earner’s own income or 50% of the spouse’s benefit.)

- Traditional employer pension: $________

- Part-time income: $_________

- Other: $________

- = $________

- This is how much you need to make up for each year in retirement.

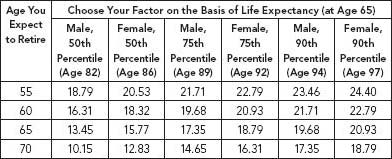

- 3. To find out how much you actually need in the bank when you retire, multiply the amount above by the factor below:

Note: This assumes a real rate of return of 3% after inflation and that you’ll begin to take Social Security benefits at age 65.

- $________

- 4. If you expect to retire before age 65, multiply your Social Security benefits from part 2 by the factor below:

- At 55, your factor is 8.8

- At 60, your factor is 5.7

- + $________

- 5. Multiply your savings to date by the factor below (including the money you’ve stashed in a 401(k), IRA, or other retirement plan):

- If you plan to retire in

- 10 years, your factor is 1.3

- 15 years, 1.6

- 20 years, 1.8

- 30 years, 2.4

- 35 years, 2.8

- 40 years, 3.3

- –$________

- Total additional savings needed at retirement: $________

I Also Need to Know…

Q: Why do women need to replace more income than men?

A: Women live an average of seven years longer than men, they are paid less throughout the course of their career—about 81 cents for every dollar a man makes—and they often don’t take as much risk in their investments as men do. Add to that the fact that many women leave work for extended periods of time to have children and care for their parents. In the end, women have to work harder to save for retirement.

Q: What if I’m not on track to have enough?

A: Well, for starters, you’re certainly not alone, as I said earlier. But that doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t do all you can to try to catch up. My first tip may sound too simple, but the best way to make up for lost time is to save more. Pinch your pennies, cut out extras, and put that money into your retirement accounts. Understand that you can spend $100 on a pair of shoes or you can instead allow that money to grow tax free in an IRA. Those pumps may look snazzy as you’re trotting about town today, but down the road, that $100 could grow enough to pay a year’s worth of gas or water bills.

Here are a few more ways to make up for lost time:

- Work a little longer. Putting in a few more years of 9 to 5 can have a huge effect on the balance in your retirement fund. If you can delay taking Social Security benefits as well, you’ll be even better off.

- Plan to pick up a part-time job. You might find that once you’re retired, having all that time on your hands isn’t all it was cracked up to be. If that’s the case—or you need some extra cash—why not find some part-time work you enjoy? Look for something you’ve always wanted to do, so it’s more hobby and less chore.

- Scale back. Maybe your dream is to travel a few times a year. Instead you limit yourself to twice a year to save a little extra cash. You can still do the things you want to do, just do them less frequently or find other ways to loosen up your budget.

- Bank your windfalls. The average annual individual tax refund is more than $2,000 a year. If you put that money into an IRA every year, it would go a long way toward supplementing your retirement funds. Ditto for holiday bonuses, birthday checks, or the money you free up when you pay off your car and have an extra $300 or $400 a month.

Q: Are the retirement calculators on the Internet legitimate?

A: As always, it depends on which site you’re visiting, but most personal finance magazines and financial institutions offer a version. If you stick to well-known and well-respected sites, you’ll be able to generate a good estimate like the one above. In fact, I like to see people use a few different calculators to come up with a consensus estimate, so to speak, of what they need to save.

91. How do I make my retirement funds last as long as I do?

A: This question tops everyone’s list when it comes to retirement. We’re all living longer these days, and unexpectedly cruising by age 85 or 90 can have you struggling to make ends meet during your final years. There are a few things you can do to budget your way through retirement so that you’re covered until the end.

- Know what you’re aiming for. You can use a calculator on the Internet to figure out your life expectancy (I like this one, from Wharton: gosset.wharton.upenn.edu/mortality/) or you can just play it safe and plan on living to be 90 or 95. If you have a strong family history of longevity, plan to be 100. If your family is prone to disease, go slightly shorter. When in doubt, however, it’s best to overshoot by a year or two.

- Withdraw like a skinflint. In general, you can withdraw 4% of your retirement savings each year and know your money should last as long as you do. That 4%, however, is a moving target. If the market is down and your accounts are down as a result, your 4% this year will be less than it was last year. If the market is up and your accounts are similarly up, your 4% will be heftier.

- Give yourself a checkup. Even if you’re adhering to the 4% rule, every couple of years take a look at where your portfolio stands and whether you’re on the right track. You can use the Ballpark E$timate once again, or T. Rowe Price has a helpful tool on its Web site, at www3.troweprice.com/ric/RIC/.

Immediate annuities, that will take some of your money and return it to you in a guaranteed stream of income. For more on this, see “What is an annuity?” in Chapter 10.

I Also Need to Know…

Q: Is it possible to save too much for retirement?

A: People always say you can never save too much, but that’s most likely because the majority of Americans aren’t in danger of saving too much. Most Americans save way too little. But you can, in fact, be too conservative when it comes to retirement. If you funnel every last cent into savings for the majority of your working life, you’re probably going to miss out on meaningful experiences, such as family vacations. You don’t want to shortchange the present for the future. Second, your retirement should be an enjoyable time, but the idea isn’t to make it to the end with hundreds of thousands of dollars left over, only to look back and wish you’d taken that cruise when you had the chance. It’s all about balance. Remember, as you age, you’re likely to get less and less mobile, which makes hiking in Tuscany a reach.

Q: Should I continue investing in the market up until the day I retire?

A: Yes. Unless you have more than enough to sustain you, you need the growth of the market to keep you ahead of taxes and inflation. In general, you’ll want to reduce your exposure to the market by 1 percentage point for each year you age. So, while at age 55 you’d want to have 45% of your assets in a diversified stock portfolio, when you hit 65 that number drops to 35%, and at 75, you should be at 25%.

THE STATS

- 24%: The amount by which Americans entering retirement will have to reduce their standard of living if they don’t want to outlive their money.

- $60,000: The typical balance in the retirement plan of a 55-year-old.

- $229: The typical monthly retirement contribution that a 55-year-old makes.

- 70%: The percentage of older workers who are planning to work in their retirement years.

92. Where should I live when I retire?

A: We spend a lot of time saving for retirement. We crunch the numbers to see how much we’re going to need, and we put strategies in motion to make sure that money lasts as long as we do. Where we live plays a big role in that equation. One way to be sure that your money lasts a longer period of time is to move somewhere less expensive.

You need to start this quest with a little soul searching. Are you thinking of a tropical paradise or of a small town instead? Do you want a condo in a retirement community? Do you want to be near your family? What do you plan to do in your retirement? If you want to volunteer, take classes, or even work, you need to look at an area that would support those opportunities.

Once you figure out what kind of atmosphere you’re looking for, think about your cash flow. Life expectancies are going up, which means that your money needs to last longer, which means that you need to spend less, save more, or work longer. More than ever, there’s pressure to stay within your budget, because the last thing you want is to be overextended financially. Make sure you evaluate not only the cost of the home you buy or rent but also maintenance, taxes, and the cost of living in that area. (For more on how to make these estimates, turn to “I’m considering buying a home in a new area. Is there a way to estimate how much it will cost me to live there?” in Chapter 7.)

Finally, think long term. You want to consider whether there is a good hospital nearby, and if there is a public transportation system that can get you around if you’re no longer able to drive. Spend a week—or better yet a summer (rent something)—in the town or city to see what activities are available and what the other residents are like in terms of age and interests.

I Also Need to Know…

Q: I’ve heard that I should pick a state that doesn’t have income tax. Is that true?

A: Don’t base your entire decision on income taxes, but it is a factor to consider. Although many retirees opt for no-income-tax states, nothing in life is free. Many of these places charge higher property taxes, so that’s something to look into if you buy, and sales taxes are often higher as well.

Q: What should I look for in the home itself?

A: You want to make sure you can afford it. But beyond that, look for features that could accommodate you as you age. You may be able to get around just fine now—I know plenty of people in their sixties who still go the gym daily—but you need a home that will support you when that’s no longer possible. That means gravitating toward single-level houses and apartments. You should also look for wide doorways that will accommodate a wheelchair, should you ever need one, and bathrooms that will allow you to install handrails and a larger shower stall with a seat, if need be. The rooms should be small enough and laid out in a way that you can get from place to place easily.

93. When should I begin to collect my Social Security benefits?

A: You can start collecting anytime after age 62—but that’s not necessarily when you should. In fact, there is no magical age when it comes to tapping Social Security, but there’s one thing you need to keep in mind: The longer you wait to take your benefits, the more your monthly check will be.

For each year you delay collecting, the Social Security formula increases the amount of your payments by about 8%. On top of that, the amount is also adjusted yearly for inflation. That means you could feasibly get a 9%, 10%, or even 11% increase for each year you wait.

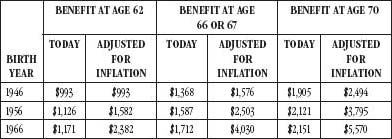

Here’s what that difference looks like:

Benefits are based on a $50,000 annual salary at retirement.

Bottom line: If you can hold off until you reach full retirement age at 66 or 67 (depending on when you were born), great. Wait until you’re 70, and that’s even better. In fact, quick math reveals that depending on how your retirement accounts are allocated, you may be well advised to spend down your own investments before tapping into Social Security benefits, because few investments can be counted on to provide a yearly guaranteed return that large.

THE STATS

- $1,089: The average monthly benefit for a retired worker, as of November 2008

- $536: The average monthly spousal benefit, as of November 2008.

I Also Need to Know…

Q: How are my benefits calculated?

A: The amount you receive from the SSA is based on the earnings throughout your time in the workforce. First, the administration adjusts the earnings to account for changes in average wages over time, and then it averages your 35 highest-earning years. This is why if you retire early after working only from ages 22 to 50, for example, your Social Security benefits may decrease because you only worked 28 years, not 35. Those seven years when not bringing in a paycheck will be factored in as zero income, dragging your overall average down.

Q: If I start collecting Social Security benefits at 62, will that affect my spouse’s benefit amount as well?

A: It will. Your spouse will see even more of a reduction in benefits than you will if you begin collecting at 62. He or she could lose up to 35%, or $175 from a $500 monthly check. Check out the chart below, from the SSA, that shows what a $500 spousal benefit would be reduced to if the retiree takes benefits at age 62 instead of at full retirement age:

RETIREE’S BIRTH YEAR: 1946

FULL RETIREMENT AGE: 66 years

SPOUSE’S MONTHLY BENEFIT: $350

PERCENTAGE OF REDUCTION : 29.17%

RETIREE’S BIRTH YEAR: 1956

FULL RETIREMENT AGE: 66 years 4 months

SPOUSE’S MONTHLY BENEFIT: $341

PERCENTAGE OF REDUCTION : 31.67%

RETIREE’S BIRTH YEAR: 1966

FULL RETIREMENT AGE: 67 years

SPOUSE’S MONTHLY BENEFIT: $325

PERCENTAGE OF REDUCTION : 35.00%

Q: I’ve heard that if I started taking Social Security benefits early, I can have a do-over. How does that work?

A: This is called double-dipping. Essentially, if you jumped the gun and started taking your benefits at age 62—as many people do—you can file a form 521 now (or after you hit full retirement age) and pay those benefits back, no interest required. You’ll then be eligible to receive the larger benefit as if you’d been waiting all along.

There are, however, a few things you need to know. For starters, timing matters. If you take early benefits at 62 and pay them back at 70, you’re going to increase your standard of living far more than if you took the benefits at 62 and paid them back at 76. Why? Because your life expectancy at age 76 is going to be shorter. So you’ll receive the bigger payments for a shorter period of time. Not only that, but the longer you wait to file the 521, the more money you’ll have to pay back. So you want to aim to pay the money back by age 70, if you can.

Also, it’s important to note that this takes a lot of foresight. The key to making it work is having the money in pocket to pay back. Some people see double dipping as a strategy. They take the money starting at age 62, stash it where it will earn some interest for the next seven or eight years, and then pay it back. It’s an interest-free loan from the government, more or less, and it’s made even more attractive by the fact that the amount you pay back isn’t even adjusted for inflation. But if you end up squandering the money or losing it in a risky investment, you’re stuck with the lower benefit for life. You have to plan well and have another source of income you can draw on in the meantime—a retirement account or part-time job.

Last, there is always the chance that the government will eliminate this loophole in the Social Security system, sticking you with the lower payout, though it doesn’t seem likely. When I called the SSA, I was told that the agency is very willing to accept 521 forms.

THE MATH

Let’s take the retiree from the chart in Chapter 10.

He had a final annual salary of $50,000. He elects to take the $993 a month starting at age 62. According to the SSA, his life expectancy is about 19 more years. Over those years, he’ll collect a total of $226,404.

Now, if he pays back his benefits at age 70 ($95,328) and begins taking the adjusted monthly amount of $2,494 instead, he’ll collect $329,208 during his remaining 11 years.

He comes out $102,804 ahead if his life expectancy remains the same.

But these days, more and more people are outliving their life expectancies by 5, 10, and even 15 years. If he lives just another 5 years, add $149,640 to his pot. Another 10, and you can multiply that by two for a total of $533,160 collected from the SSA. Had he continued to take the $993 and lived this long, he’d have only taken $345,564 in benefits.

94. How do I earn money in retirement without losing Social Security benefits?

A: If you’re under full retirement age—which, according to the age stipulated by the SSA, will be set for the next 18 years or so at age 66—$1 will be deducted from your benefit for every $2 you earn above the annual limit. In 2009 and 2010, that bar is set at $14,160. Note that the SSA looks at your gross, not net, wages when making these calculations, which means your full salary, before deductions for taxes, insurance, and 401(k) contributions.

This calculation is where it starts to get a bit complicated. The rules change when you enter the year that you will reach full retirement age (January 1 of the year you turn 66.) At that point, you can earn more, up to $37,680 for 2009 and 2010. Above that amount, $1 will be deducted from your benefits for every $3 you earn.

Once you turn 66, you will begin to get your benefits regardless of your earnings. From that point on, you can earn as much as you want and your Social Security benefits will remain the same.

Example 1

Let’s say your birthday is in September and you’ll be 66. You earn a salary of $60,000 a year, which is $5,000 a month. You’ll earn $40,000 from January through August, and your Social Security benefits should be $1,400 a month. You’ll receive $773 less this year because your income from work during the months that you are still younger than full retirement age is $2,320 over the annual limit.

Example 2

You’re 64, earning the same salary of $60,000 per year. Because you’re earning $45,840 over the annual limit of $14,160, your benefit is wiped out. You would have to earn less than $28,000 to earn any benefit whatsoever.

Unfortunately, there is no way to get around losing a portion of your benefit if you’re still earning decent money under age 66. But my advice to you, if you’d like to continue to work, is to delay taking your benefit, if at all possible. Not only does your benefit see a hefty increase for each year you put off taking it until you reach age 70, but also, if you’re going to be losing a portion—or even all—of your money anyway, you’re better off waiting. You can read more about the advantages of delaying your Social Security benefits in Chapter 10 in response to the question “When should I begin to collect my Social Security benefits?”

I Also Need to Know…

Q: What if I retire in the middle of the year?

A: If you retire in the middle of the year, a monthly income threshold replaces the annual limits. In 2009, the monthly limit is $1,180 (the yearly limit, $14,160, divided by 12). You can receive full benefits in any month that you do not earn more than that, regardless of how much you earn the rest of the year.

Q: What income counts toward those totals?

A: Any income you earn from work or self-employment will count against your Social Security benefits if you’re younger than 66. But investment income, such as IRA or 401(k) distributions, interest, pension, and inheritances, won’t be included. These are considered “nonwork” sources of income and they don’t affect your Social Security benefits.

95. How do I transition into Medicare?

A: If you’re already receiving Social Security benefits, you’ll be enrolled in Medicare when you turn 65. You don’t need to do a thing, except watch the mail for your Medicare card, which should come about three months before your birthday.

If you haven’t tapped into your Social Security benefits, you need to apply for Medicare by calling 800-772-1213. If you want to apply for both at the same time, you can do that online at www.socialsecurity.gov/applytoretire.

Note: Your full retirement age in the eyes of the SSA isn’t until age 66, but you’ll still be eligible for Medicare at 65 as long as you’ve paid into the Social Security system for at least 10 years or you are eligible to receive benefits because of your spouse’s earnings. (This is a requirement of Medicare at any age, not just 65.)

Once you’re enrolled, of course, you need to navigate the system. Medicare has four parts:

- Part A: This is hospital insurance that helps cover inpatient care in hospitals, as well as nursing facilities, hospice, and home health care. It does not, however, cover long-term care if you end up in a nursing home. You typically will not pay a premium for this coverage, as long as you or your spouse paid Medicare taxes while you were working. If you didn’t, you can usually buy part A coverage. In 2009, the premium is up to $443 a month, and in most cases, you will also have to purchase part B.

- Part B: This is medical insurance for doctors’ visits, outpatient care, and preventive care. You will pay a monthly premium for this service, $96.40 in 2009. (If your income is above $85,000 as a single filer or $170,000 as a joint filer, your premium will be higher. The amount increases with your income, with the highest premium at $308.30 for single filers who make more than $213,000 and joint filers who earn more than $426,000.) There is also an annual deductible of $135 in 2009, and you will typically pay 20% of the cost of whatever service you receive upfront.

- Part C: The Medicare Advantage Plans of part C are like HMOs and are run by private health insurance companies. They include a combination of parts A and B, and often D. The cost will vary depending on the individual provider, and you must have parts A and B to join. You will have a network of doctors and hospitals to choose from.

- Part D: Prescription drug coverage, which defrays the cost of prescriptions. This part is a rider to parts A and/or B—you can’t get it alone. You’ll pay a monthly premium, a deductible, and copayments, all of which vary by plan.

So how do you know what you need? The first step is deciding whether you want what’s called Original Medicare, which can include part A or B, or a Medicare Advantage Plan, which includes the services of A and B and is provided by a private insurer. Compare the costs and the coverage and remember that under Original Medicare, you’ll have your choice of doctors and hospitals, while under a Medicare Advantage Plan, that option will be limited to your particular plan’s network.

Then you must decide if you want prescription drug coverage, and believe me, you do. If you’ve chosen a Medicare Advantage Plan, you can get it through your provider, and if you’ve gone with Original Medicare, you can join Part D.

Medicare has a helpful tool on its Web site that can help you compare plans. Go to www.medicare.gov and then click on “Compare Health Plans and Medigap Policies in Your Area” or “Compare Medicare Prescription Drug Plans.” You can also get free counseling through your State Health Insurance Counseling and Assistance Program. Find yours on Medicare’s Web site at www.medicare.gov/contacts/staticpages/ships.aspx.

I Also Need to Know…

Q: What isn’t covered under parts A and B?

A: You can find a full list on Medicare’s Web site, but here is a sampling:

- Chiropractic services

- Dental care and dentures

- Eye exams and glasses

- Hearing exams and aids

- Insulin

- Yearly physicals (a one-time physical is covered)

- Foot care

To fill in all or some of those gaps, you can purchase what’s called a Medigap policy, which are sold by private insurers. It’s an extra expense, but it will help cover the services that Medicare won’t, plus a portion of your copayments and deductibles. You’ll pay separate monthly premiums—one for part B and one for the Medigap coverage. If you think you need a Medigap policy, you should buy one during the first six months after you turn 65 and enroll in Medicare. After that, your ability to buy gap coverage is often limited. For more information about Medigap policies, see www.medicare.gov/medigap/Default.asp.

Note: You don’t need a Medigap policy if you are enrolled in an advantage plan (part C).

Q: My employer is one of the few still providing coverage after retirement. Do I need Medicare? And what if those benefits go away sometime in the future—can I join then?

A: Check with your employer’s human resources department to find out exactly how the company’s coverage plays into Medicare, but in general, health insurance through your former employer is treated as secondary. In other words, it fills in the gaps left by your Medicare coverage. In most cases, you’ll probably want Medicare parts A and B, and then your private health insurance will most likely cover prescription drugs and anything else.

If your benefits are canceled, you have the right to enroll in part C or part D. You must do so within two months of cancellation of coverage from your former employer. One other thing to keep in mind: If your benefits are canceled and you don’t already have part B, you’ll have to wait until the next general enrollment period to sign up. This period occurs in the first quarter of each year, and your coverage won’t start until July. To avoid gaps in your retiree benefits—particularly if you anticipate changes—get a jump on things so that you don’t experience a lapse in coverage.

Q: I can’t afford Medicare’s prescription drug coverage. Do I have any options?

A: Yes. There are federal programs to assist you, provided you fall under the income limitations to qualify.

FEDERAL LIMITS IN 2009

- Single: Your 2008 income must have been less than $15,600 and your assets (investments and balances of savings and checking accounts) must be less than $11,990.

- Married and living together: Your 2008 income must be less than $21,000 and your assets must be less than $23,970.

Once you qualify, you have to join part D, and then you’ll receive assistance to meet the premium, help meeting your yearly deductible, and a reduction in coinsurance and copayments.

Aside from this assistance, your state will also offer what’s called a Medicare Savings Program. These programs vary by state, but in general, they will help you pay your premiums and in some cases, your deductibles and coinsurance. To qualify, you must be enrolled in part A and meet income limitations.

LIMITS FOR MEDICARE SAVINGS PROGRAMS IN 2009

- Single: Your monthly income must be less than $1,190 and your assets must be less than $4,000.