The pressure of a burgeoning law practice took a toll on Bautzer’s psyche. His famous clients were paying a lot of money for his services; they expected a lot in return. Because of their celebrity status, many felt they deserved special treatment. Temperamental and spoiled, they called at all hours of the day and night to dump their latest problem in his lap, whether large or small. They expected him to stop whatever else he was doing and fix their troubles immediately. Bautzer took these responsibilities seriously and prided himself on giving his clients his total attention.

Like an emergency room doctor, he was on call twenty-four hours a day. In a time before mobile phones, Bautzer made certain his secretary knew which restaurant, nightclub, or party he would be attending in the evening so she could contact him. Waiters frequently brought a telephone with an extension cord to his table so he could take his clients’ calls. While he enjoyed the excitement of nonstop action and the aura of importance it gave him in the community, his big-shot status came at a price. He constantly needed to let off steam.

To relieve the tension Bautzer played as hard as he worked. He gambled at card games, engaged in serial romances with starlets, and drank heavily. At the time, drinking copious amounts of alcohol was not only tolerated, it was considered a sign of maturity and manhood. The cocktail hour officially started at 5 PM and lasted all evening. Executives bragged about having “three-martini lunches” and kept private bars stocked in their offices for daytime “pick-me-ups.” Inebriation without appearing too drunk or getting sick was called “holding” your liquor, and it was considered a virtue.

Bautzer thought he could hold his liquor, but often he couldn’t. When he drank, his personality changed, reverting to the barroom brawler of his youth on the docks of San Pedro. “Watch out for him,” Howard Hughes warned publicist Paul MacNamara. “When he gets on the sauce, he can be trouble.” That his uncle had died of alcoholism at age thirty-two should have been a warning.

Lawyers are disproportionally high candidates for alcoholism, and Bautzer was a textbook example. Current studies show that nearly 30 percent of lawyers who have been practicing for twenty years or longer have an alcohol-use disorder—triple the average for the general population. The situation is so prevalent that the California State Bar requires all lawyers to take a one-hour educational course in preventing substance abuse once every three years. Most lawyers who drink heavily are able to get away with it because their careers do not suffer. They are known as “highly functioning alcoholics.” The same personality traits that allow them to succeed professionally make it possible for them to keep their drinking from affecting their jobs. They are typically perfectionists and overachievers, with a competitive workaholic nature and a strong physical constitution. Bautzer possessed all of these traits, and so he never thought he needed to stop drinking. Moreover, he didn’t always drink too much. Sometimes he could consume one or two glasses and go home without incident. But as his practice grew, his consumption of alcohol increased, and so did the frequency of bad behavior under the influence.

The trouble would start in the most innocuous way. Bautzer would be talking with his dinner companions, apparently unaffected by the number of cocktails he had downed. His attention would move to an adjoining table where other diners were engrossed in conversation, oblivious to their renowned neighbor. Suddenly Bautzer would take umbrage at something—anything. It could be a sidelong glance, a laugh, a word. In an instant he was on his feet and moving toward an innocent person.

For much of the twentieth century, fistfights were part of the code of manhood, a holdover from the days when gentlemen fought duels to settle disputes and defend their honor. “Real men” weren’t afraid to march onto the battlefield and back up their words with action. Celebrities like Ernest Hemingway, Norman Mailer, Frank Sinatra, and even studio boss Louis B. Mayer were renowned brawlers. Nevertheless, Bautzer’s drunken battles went far beyond the bounds of the era’s social norms.

Friends tried to stay ahead of Bautzer, but it was difficult. “Greg wasn’t a staggering, falling-down drunk,” remembered MacNamara. “You might not even know he was in trouble. He simply turned off his lights when he got a certain amount of firewater aboard, and when that happened, look out. He would change in the blink of an eye from a charming, gentle fellow to an enraged bull.”

MacNamara explained the problem further: “Greg had a faulty connection in his radar set that would sometimes snap and give him incorrect messages, and the message that he would receive would be from some total stranger who wasn’t trying to send him a message at all. The message he mistakenly received was to the effect that he, Greg Bautzer, was a son of a bitch. This, of course, would enrage Greg, and he would turn on the stranger, who would be sitting in all innocence a few tables away, sipping his wine, oblivious that a Pearl Harbor attack was on its way. This led to all kinds of misunderstandings, spilled drinks, and uncalled-for blows. Usually there wasn’t too much damage, but it would be difficult for Greg’s friends to explain to the victim and his friends.”

MacNamara was with Bautzer at the Racquet Club bar one night when he saw Bautzer take a sudden dislike to a stranger across the room. The man was doing nothing but sitting there, finishing a drink. Bautzer’s face clouded. His eyes narrowed. He began insulting the man, and then he challenged him. A bartender named Tex whispered to MacNamara, “Get your friend outta here. That guy he’s monkeying with is trouble.” Sure enough, the stranger was arming himself with a glass ashtray and was flanked by two bruisers. Just when it looked like all hell was going to break loose, the club’s bouncer walked in, carrying a club. “Bautzer cooled off,” said MacNamara, “but it had been close, and it had been his fault.” Bautzer was fortunate someone stepped in to stop it. The formidable stranger was on the Los Angeles Rams football team. The next day MacNamara told Bautzer how lucky he had been. “He looked at me funny and wanted to know what I was talking about,” recalled MacNamara. “He had no recollection of what had gone on. And when I gave him the details, he just shook his head.”

Bautzer was relatively sober the night he encountered Humphrey Bogart in a bar. The star enjoyed needling people. He would cast witty insults to see just how far he could push someone to provoke a reaction. “Bogie thought of himself as Scaramouche,” said writer-producer Nunnally Johnson, “the mischievous scamp who sets off the fireworks, then nips out.” In a town crowded with oversized egos, he found many targets. Bogart was democratic; he insulted friend and foe alike, and no one was safe, neither stars nor executives. “Bigwigs have been known to stay away from brilliant Hollywood occasions rather than expose their swelling neck muscles to Bogie’s banderillas,” said Bogart’s favorite director, John Huston. Irving “Swifty” Lazar, Bogart’s agent, thought that the star occasionally hurt people but believed that his usual target was someone who could defend himself. No doubt Bogart took one look at Bautzer and saw a bull’s-eye. In a few minutes, he had gotten the unflappable debater angry. “I’m going to beat you to a pulp,” Bautzer told him.

“You’re not going to hit an old man, are you?” asked Bogart, who was then in his fifties.

“Well, stop needling me,” said Bautzer.

“You know, Greg, you have a bad pattern to your life,” said Bogart with mock sadness.

“That does it.” Bautzer got to his feet and ordered Bogart to step outside.

“Go on,” said Bogart. “You go first. Everyone will follow us if we both go out together. Let’s fight in private.” Bautzer stormed out. Bogart watched him go, paused, finished his drink, and then ordered another. Five minutes went by. Bautzer walked back in, puzzled. “You look cold,” Bogart said to him. “Come in. Warm up. Have a drink.” Bautzer stared at him for a moment, then he got the joke. He laughed. Laughter could change Bautzer’s mood.

Actor George Hamilton had a number of run-ins with Bautzer. The first was at the New York nightclub El Morocco, where friends were helping him get over a breakup with actress Susan Kohner. To the great displeasure of her father, talent agent Paul Kohner, Bautzer had lured the dark-haired young beauty away from Hamilton by serenading her bedroom window with a musical quartet. “And who should come in but Susan, and with Greg Bautzer,” said Hamilton. “He kept dancing her by my table, dipping her dangerously close to me, rubbing her in my face. I got upset and called him aside. ‘You’ve got no manners,’ I told him. He jumped into action and put up his dukes. ‘You want it right here, kid? How do you want it? Fists? Guns? Karate? You name it.’ I backed off. I couldn’t do a duel in front of Susan, not at El Morocco.”

Hamilton got a second chance at a dinner at Hedda Hopper’s home. When Bautzer gave him the opportunity, he took Bautzer outside and knocked him flat. To Hamilton’s surprise, Bautzer admired him for it. When Hamilton ran into Bautzer on the street in Beverly Hills, Bautzer smiled, called him “compadre,” and hugged him. After that, whenever the two met, Hamilton was Bautzer’s compadre.

Bautzer’s favorite way to relieve tension was to seduce beautiful young actresses. When he wasn’t drinking, fighting, gambling, playing tennis, or arguing a case, Bautzer was wooing. He was a master at giving a woman what she wanted. MacNamara analyzed his system. “His looks were enough to get him started, and his technique was always the same,” said MacNamara. “First, long-stemmed roses came in two-dozen bunches. They were followed by a small but expensive fur piece. Then came an invitation to Acapulco for a long weekend. It never failed to work.”

There is no way to know how many actresses Bautzer dated, but there was certainly a long trail of stems and fur between Hollywood and the beach at Acapulco. In December 1941, after breaking up with Dorothy Lamour, he had stepped out with the legendary Marlene Dietrich, who would also one day be a client. In 1942, he paid actress Carol Bruce some attention. In 1946, he courted the gorgeous Marguerite Chapman, who later married and divorced his former law partner Bentley Ryan. In June 1947, Bautzer was reported to be “stardusty” with Audrey Young, the future Mrs. Billy Wilder, at the same time that he was seeing Greer Garson. In New York one month later, he was “cruising the glitter spots” with Cat People actress Jane Randolph. In the early 1950s, Bautzer dated buxom blonde Barbara Payton. She had a reputation for sleeping with every man she met, including Howard Hughes, who supposedly said she would perform any sexual act a man desired. Bautzer stopped seeing her after just a few weeks when he realized she was mentally unstable. Her bohemian lifestyle shortened her career and led to an early tragic death after a degrading drug-addicted existence as a street prostitute. It has been reported that she and Bautzer were engaged, but there is no evidence of it.

Bautzer’s style didn’t work on every woman, though. In 1953, he tried his technique on Ann Rutherford, who had played Carreen O’Hara in Gone with the Wind. She was hesitant to accept his invitation to dinner and asked a friend, actress Ann Miller, what she thought. Miller had been out with Bautzer. “He was suave, gallant, and eloquent,” said Miller, “and he had the smoothest line of blarney I’ve ever heard.”

“Do you think he’ll give me the same line?”

“Let’s have some fun,” said Miller. “I’ll tape record what I remember him plying me with, and then let’s compare it with what he tells you.”

“Will you bring the tape to my house?” asked Rutherford. “I’ll play it back as soon as I get home and make the comparison.”

Rutherford had dinner with Bautzer that night. About midnight she called Miller laughing hysterically. “You told me, but I really didn’t believe it,” said Rutherford. “It’s true! It’s true! I played your tape as soon as I came home and it’s just as you said. He gave me the same flowery line—how beautiful I was, how he would walk on water for me, how he loved me more than life itself—all the bunk. I had fun, though. He really is a charmer.”

Bautzer enjoyed his status as a famous playboy. It is cliché to say that variety is the spice of life, but Bautzer had his pick of the most desirable women in the world. According to his secretary, Lea Sullivan, some actresses even pursued him seeking a date. They saw no reason to stand on ceremony and called his office to ask him out. Sometimes these ladies became so insistent, Sullivan had to tell the switchboard operator not to put the calls through. In truth, for most of his life Bautzer’s first love was his career, and that commitment always came first.

In 1951, Bautzer turned forty. By no means middle-aged, he had nonetheless been a Hollywood fixture for fifteen years. His status was beginning to provide him with leadership opportunities in the community. In 1953, Bautzer was named by Conrad Hilton to the Citizens’ Committee for Major League Baseball, which hoped to bring the St. Louis Browns to Los Angeles. In 1954, he joined the board of directors of National Theaters Inc., a company created to control Twentieth Century-Fox’s former theaters after the federal government’s 1948 determination that studios owning theaters constituted a violation of antitrust laws. In 1955, he was elected to the board of the Pepsi-Cola Bottling Co. of Los Angeles. Alfred Steele, chief executive officer of Pepsi, had recently become Joan Crawford’s fourth husband. Crawford used her influence to put Bautzer on the board of directors.

Bautzer was also a board member and chief counsel of the Fidelity Pictures Corporation, which produced low-budget films for release through Republic Pictures. The company made several interesting pictures employing top-notch talent, including House by the River, directed by veteran director Fritz Lang; Woman on the Run, starring Ann Sheridan; Rancho Notorious, also directed by Lang and starring Marlene Dietrich; The San Francisco Story, starring Joel McCrea and Yvonne De Carlo; and Montana Belle, directed by veteran director Alan Dwan and starring Jane Russell. Bautzer had a hand in casting the films. Ann Sheridan and Marlene Dietrich were both his clients and romantic interests. His former steady girlfriend Ginger Rogers also made a comedy for Fidelity called The Groom Wore Spurs. In it, Rogers plays a lawyer trying to rescue a cowboy actor from gangsters to whom he owes gambling debts, only to end up marrying him. New York Times critic Bosley Crowther panned the picture, saying, “The only thing funny about this picture is that it is called a Fidelity film.” Hollywood could laugh at itself. When the trade paper Hollywood Box Office ran an article about Fidelity’s production slate of six films, the title read: FIDELITY WILL FILM SEX FEATURES IN 18 MONTHS. It was most likely a misprint, but there were those who thought it alluded to Bautzer’s reputation with the ladies.

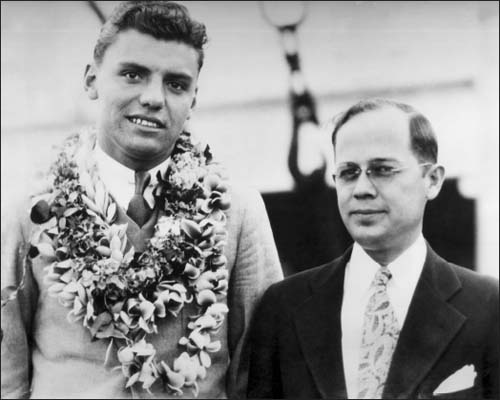

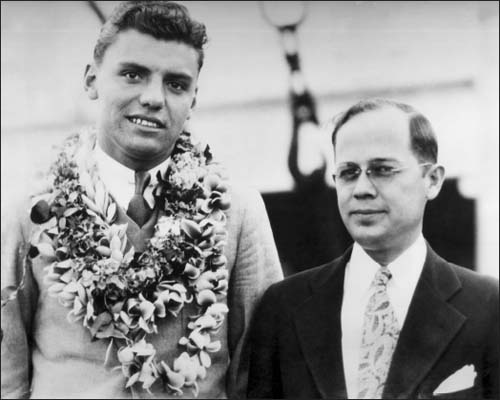

Bautzer was captain of the USC Trojan Debate Squad. Here he is arriving in Honolulu for international debates with fellow student Ulysses S. Mitchell on April 15, 1934. Courtesy of University of Southern California, on behalf of the USC Special Collections

In court on August 9, 1938, fighting extradition of Freeman Bernstein, a.k.a. the King of Jade. UCLA Charles E. Young Research Library Department of Special Collections, Los Angeles Times Photographic Archives, © Regents of the University of California: UCLA Library

Questioning police officer Homer D. Fitzer at an inquest over the fatal shooting of Charles Ray Davey after a high-speed chase. The verdict was justifiable homicide. UCLA Charles E. Young Research Library Department of Special Collections, Los Angeles Times Photographic Archives, © Regents of the University of California: UCLA Library

“We won’t get married for a while” was the caption of this widely published news photo that introduced Greg Bautzer, “USC Law School Graduate,” to the world as the fiancé of rising star Lana Turner. Associated Press Photo

At the Brown Derby Restaurant in Hollywood with Lana Turner. Bob Cobb Family Collection

The May 1938 premiere of Alexander’s Ragtime Band at the Carthay Circle Theater with French actress Simone Simon. Photofest

Back at the Brown Derby in Hollywood with Lana Turner for a cup of coffee. Bob Cobb Family Collection

Despite claims to the contrary, Bautzer and Turner did reunite upon his return from the navy. Here they hold hands under the table at Club Mocambo on December 6, 1945. Photo by Nat Dallinger, © Dallinger Photo Collection

Dancing with Turner at the Stork Club in New York City, March 1946. Photofest

The two men responsible for Bautzer’s early success: Billy Wilkerson (left), publisher of the Hollywood Reporter, and Joe Schenck (center), chairman of Twentieth Century-Fox. Wilkerson Archives

Arriving with Dorothy Lamour at Ciro’s nightclub, July 29, 1941. Photofest

A clown competes for Dorothy Lamour’s affection at the circus. Photofest

At the Brown Derby in Hollywood with Merle Oberon during one of many breakups with Lamour. Bob Cobb Family Collection

Law school idol Jerry Giesler (right) defended Bugsy Siegel (left) against murder charges before Bautzer went toe to toe with the gangster; the two are seen here on November 15, 1940. © Bettmann/CORBIS

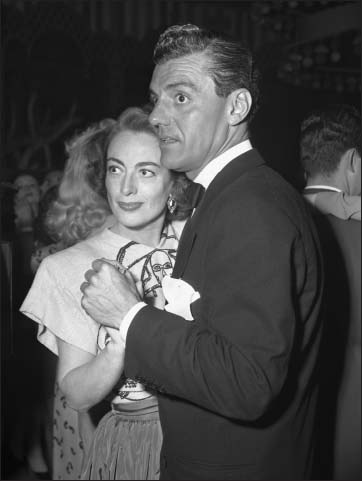

On the dance floor with Joan Crawford at Club Mocambo on May 23, 1946, shortly after she won the Academy Award for Mildred Pierce and divorced husband number three, actor Phillip Terry. Photo by Nat Dallinger, © Dallinger Photo Collection

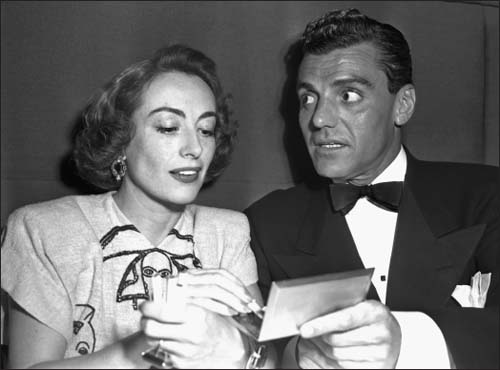

Bautzer gave Crawford a gold cigarette case inscribed with the words FOREVER AND EVER, lyrics from the song “Always and Always,” which she sang in the film Mannequin. Photo by Nat Dallinger, © Dallinger Photo Collection

Arriving at Ciro’s with Crawford in one of the Cadillacs she gave him. Photo by Nat Dallinger, © Dallinger Photo Collection

Crawford’s feathered hat attracted stares at LaRue restaurant. Photo by Nat Dallinger, © Dallinger Photo Collection

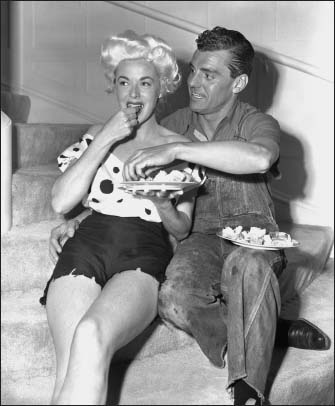

Actress Marguerite Chapman dressed as Daisy May and Bautzer as Li’l Abner for a comic strip–inspired costume party at the home of radio manufacturing magnate Atwater Kent on June 6, 1946. Photo by Nat Dallinger, © Dallinger Photo Collection

With actress Joan Caulfield at Ciro’s, March 20, 1947. Photo by Nat Dallinger, © Dallinger Photo Collection

Joan Crawford was enraged by Bautzer’s dates with Ava Gardner, seen with him here on June 5, 1947. Photo by Nat Dallinger, © Dallinger Photo Collection

Italian director Roberto Rossellini (left) with Ingrid Bergman and her husband Dr. Petter Lindström shortly before Bautzer handled her divorce. Photofest

Answering questions for the press with Lindström’s attorney, Isaac Pacht, before a court appearance in the Bergman case. UCLA Charles E. Young Research Library Department of Special Collections, Los Angeles Times Photographic Archives, © Regents of the University of California: UCLA Library

Ginger Rogers wears a mask at St. John’s Bal Masque, February 10, 1950. Photo by Nat Dallinger, © Dallinger Photo Collection

Premiere of Sands of Iwo Jima with Ginger Rogers, March 1, 1950. Photofest

Charles Farrell presents the Pimm’s Cup trophy for mixed doubles to Bautzer and Rogers at the Racquet Club in August 1950. Photofest

At the Racquet Club with Ginger Rogers and New York–based law partner Arnold Grant. Photofest

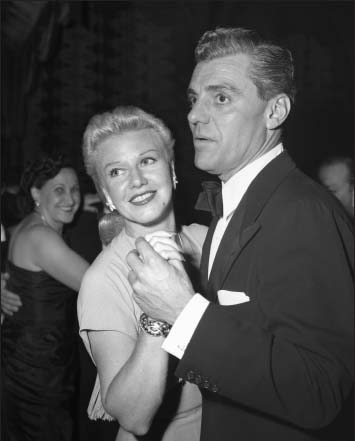

Ginger Rogers dances with Bautzer; Rogers said Bautzer was one of the best dancers she had ever met—her “social Fred Astaire.” Photo by Nat Dallinger, © Dallinger Photo Collection

At the Ice Follies with Jane Wyman, September 22, 1950. Photo by Nat Dallinger, © Dallinger Photo Collection

Dancing with director John Huston’s ex-wife, actress Evelyn Keyes, July 6, 1951. Photo by Nat Dallinger, © Dallinger Photo Collection

Back together with Wyman listening to Bob Hope tell a funny story, September 9, 1951. Photo by Nat Dallinger, © Dallinger Photo Collection

With Wyman at a Hollywood party, November 2, 1951. Photo by Nat Dallinger, © Dallinger Photo Collection

With Merle Oberon at the Screen Writers Guild Awards, March 27, 1953. Photo by Nat Dallinger, © Dallinger Photo Collection

Pia Lindström with her father aboard the Queen Mary on July 14, 1951, en route to visit mother Ingrid Bergman in England. She would not see her mother again for seven years. Photofest

At the premiere of The King and I with new wife Dana Wynter, star of Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Photo by Nat Dallinger, © Dallinger Photo Collection

Arriving at a party with Dana Wynter. Photo by Nat Dallinger, © Dallinger Photo Collection

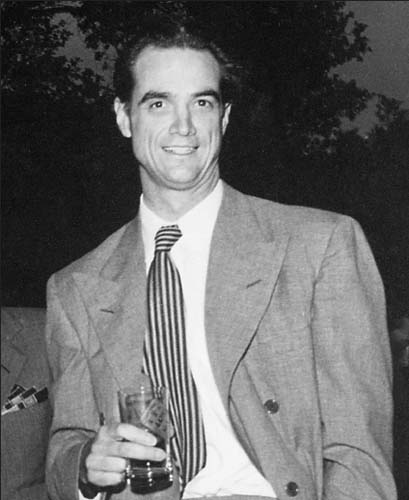

“When Howard Hughes all of a sudden says, ‘This is my lawyer,’ it makes you kind of important.” © Slim Aarons/CORBIS

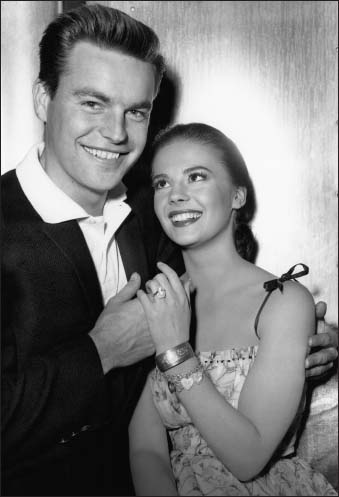

Bautzer promoted Robert Wagner’s career when the actor was only making $75 a week playing small parts. When Wagner married Natalie Wood, the couple honeymooned in Bautzer’s Palm Springs home. Photofest

With Sam Goldwyn at the Brown Derby Restaurant in Hollywood. Bob Cobb Family Collection

Frank Sinatra and wife Nancy shortly before their divorce. Photofest

Frank Sinatra with new wife Ava Gardner. Although Bautzer gave Sinatra a hard time as Nancy’s lawyer in the divorce, they later became friends. Photofest

Nancy Sinatra with Joe Schenck at a party thrown by gossip columnist Louella Parsons on July 24, 1953. Bautzer appears to be giving her good news. Photo by Nat Dallinger, © Dallinger Photo Collection

Rock Hudson and wife Phyllis Gates. The marriage was forced on Hudson by the studio; Bautzer handled his divorce and all his other legal needs. Photofest

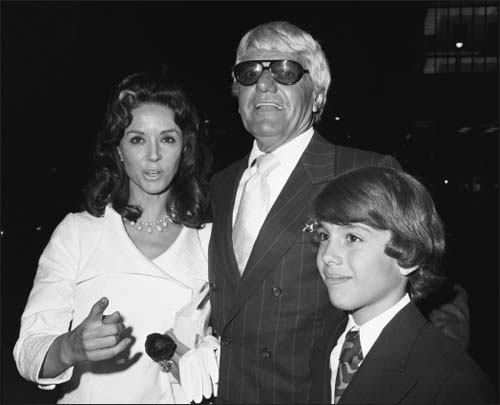

Although separated, Bautzer and Dana Wynter continued to attend public functions together. Here they are at a premiere in the early 1970s with son Mark. Photo by Nat Dallinger, © Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences